My Dad Skipped My Iraq Homecoming. A Week Later, He Called in Panic

Part One

“Your brother’s BBQ is more important.”

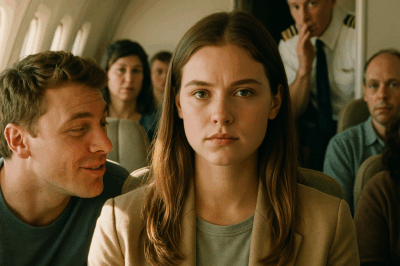

That was the whole text. No “sorry,” no question mark, not even my name at the top—just those five words landing on my screen as the plane descended over Ohio fields patched in winter brown. I stared at them while a flight attendant smiled at a man who was too tall for his seat and a baby in 19C gnawed the corner of a boarding pass like it might be a cure. The engines changed pitch. The seatbelt light dinged. My thumb hovered over the keyboard, then tapped the word I’d been using my whole life whenever I felt invisible.

Fine.

The wheels kissed the runway, the cabin applauded half-heartedly—an old ritual that always felt a little desperate—and I told myself I’d just Uber. No big deal. I’d been living on convoys and chow hall coffee for months; I could handle the quiet between here and my little rental. It wasn’t like I had a parade coming.

Dayton International smelled like melted pretzels and floor polish. Families pressed against the railing by the escalator, faces upturned, hands waving signs with names in glitter glue. A little boy in a Spider-Man shirt screamed “Daddy!” and launched himself at a man with dust in the creases of his uniform. Someone’s grandmother cried without bothering to hide it. My duffel thumped my hip as I walked through the bright tile. I kept catching myself looking for someone who knew my gait.

No one did.

I pulled out my phone, re-read my father’s text, then tucked it back into the brace on my left arm for a second like I could shove the words into a place already numb. I ordered the car. The driver—a kind-eyed man named Paul with gray hair clean as a chapel—didn’t ask. He saw the brace and the fatigue and the way people look when the place they are and the place they thought they’d be don’t match. He drove. The Civic smelled like pine air freshener. That scent always reminded me of artificial Decembers.

“Long trip?” he asked gently when we hit I-70.

“Something like that,” I said, grateful he didn’t press.

Two years patched together overseas is a hard thing to squeeze into sentences that don’t sound like you’re auditioning for a movie. You can tell people about heat that makes even your bones sweat, about dust fine as talc that turns the inside of your mouth chalky, about the morning birds sound different after explosions. You can tell them your arm will work again—sort of—and the doctors were kind and the pills made everything soft around the edges. You can tell them you have all your limbs and know other people who don’t and feel guilty for wanting more from life than just breath. None of that translates well in an Uber.

We reached my building on Finley Street. My hand hesitated on the door handle. “Thank you,” I said.

“Welcome home,” he said simply, like it wasn’t complicated.

Home was colder than I remembered, that special February cold that gets into the drywall. The thermostat blinked LOW BATTERY in a stubborn little font. Someone had pushed mail through the slot until it made a drift across the floor—pizza menus, envelopes that looked like bills, one card with fireworks on the front that had missed New Year’s by a month. The fridge held sour milk and a crusted jar of mustard. I dropped the duffel, left my coat on, and laid down on the couch. I meant to close my eyes for a minute.

I woke up to a shrieking alarm and a face in my living room that didn’t belong to me. The air tasted metallic. Paramedics. Oxygen. Hands I didn’t know doing things in quick layers. A voice too close. “You’re okay. Don’t panic. On three.” The world went black in the polite, practiced way hospital orders do their work.

When I opened my eyes, ceiling tiles blinked back. Miami Valley Hospital machines hummed in a key that reminded me of generators. A nurse with a badge that said TARA asked me the questions: name, date, what day of the week (always the trick). They told me a pipe had frozen and cracked. The carbon monoxide detector had done its job. “Another hour and you wouldn’t be here,” someone said. That sentence should land with thunder. It didn’t. It floated around the room like a balloon someone forgot to pop.

My phone buzzed on the scratchy hospital blanket. And kept buzzing.

Twenty-eight missed calls. Same number. My father’s. The man who hadn’t driven fifteen minutes to the airport because my brother had ribs to tend was now frantic because my VA check hadn’t hit his bank account and the mortgage payment had bounced.

When I finally picked up, his voice was hard with panic. “Sarah, thank God, listen—your VA check didn’t clear. Did you get yours? The bank says—”

I hung up. The monitor by my bed kept beeping in its small, patient way. I lay there and stared at the burned-out light above the sink and whispered to the new seam in my life, “Now you remember me.”

I didn’t start out bitter. Nobody does. You learn it one letdown at a time, like a slow drip wearing a groove into stone.

Lynen Avenue in Dayton smelled like mown grass in the summer and wet leaves in the fall. Our little ranch had peeling yellow siding and a maple in the front yard that dropped helicopters all over the driveway. My father, Frank, was a factory man until the plant shut down in the nineties and a man whose world was small and certain lost the parts of it he knew how to name. My mother, Carol, did hair for the neighborhood at our kitchen table. The sink drains were always tangled with someone else’s day.

My brother, David, was a star quarterback at Kettering High with a letter jacket and a future so bright the town squinted. People at Kroger recognized him by the sweat on his practice jersey and applauded when he walked past the oranges. Mom taped every article with his name to the fridge until it looked like a shrine to newspaper ink. Me? I got a certificate once for perfect attendance in eighth grade. It hung on the side of the fridge, half-covered by the electric bill and a pizza coupon.

When I was nine, I fell out of the maple and broke my arm. I can still feel the way the world went white and loud, how breath suddenly seemed optional. Dad glanced at me, paled, glanced at his watch. David had a playoff game. Mom said, “We can’t let him miss it.” Mrs. Turner, our neighbor, drove me to the ER and sat with me under fluorescent lights that made my cast look like it had been dipped in moon. “Your parents coming soon?” the doctor asked, holding my elbow like it was a fragile thing he wanted to fix. “Yes,” I lied. Fine, I told myself. Fine.

High school lined up its small rituals and I checked them off with a pen that wanted to press through the paper. David’s senior year was a parade: recruiters from OSU, Friday night lights like God turned the sky up. I won an essay prize at state. Dad shook my hand distractedly while asking David if he’d stretched. I read my piece in a half-empty auditorium. They left early to get him to the weight room. Fine.

Valedictorian felt like it should have changed something. I looked for my parents in the bleachers. They were gone—left after my speech to get David to baseball practice on time. Fine, fine, fine, like a mantra you say not because it helps but because you need a word that doesn’t set the room on fire.

When I enlisted, I thought maybe he’d notice. A daughter raising her right hand at the recruiting station isn’t nothing. Mom clutched her purse and told me I’d better not lose it. Dad laughed when the sergeant shook my hand. “She just wants that free college,” he told the room like a joke everyone should enjoy. Everyone chuckled politely. I burned and smiled. The bus left Dayton for Fort Leonard Wood. No one cried. Mom waved. Dad told me to keep my grades up. He thought I was going to college. David didn’t look up from his phone.

Funny thing about the Army: it gave me family. They weren’t perfect—Lord knows none of us were—but they noticed. Jenkins from Toledo shared his last pack of gum with me on a convoy and spit sunflower seed shells into an empty Gatorade bottle with the casual accuracy of a man who needed small rituals. Martinez kissed the tiny Bible in his chest pocket every morning and let us tease him about it because he was kinder than we deserved. Corporal Lewis, who would have given you the last sip of his canteen without looking thirsty. When you didn’t show for chow, someone knocked. When your boots went bad, someone tossed you theirs. It was as simple and as profound as that.

We were outside Fallujah the day the road broke. The horizon was a wobble of heat. The convoy rolled slow—scarred Humvees, engines complaining. The first blast wasn’t a sound so much as a fist you feel in your bones. The second was closer. The world slid sideways. Steel screamed. My left arm lit with pain so pure it felt like a song. Jenkins dragged me out, yelling my name with blood in his teeth. At the field hospital, a man with gentle hands and the kind of tired eyes you only get when your whole life is mending other people told me I’d keep the arm, but it wouldn’t be itself. We don’t talk enough about the parts of bodies that remain and don’t always come back.

Coming stateside, people said the words they’re supposed to say—hero, sacrifice, service—and I said thank you and tried to carry them like they weren’t too big for my pockets. But nights were ropey with fear and days were loud with small things: car backfires, the neighbor’s trash can lid, the UPS driver who doesn’t knock. The VA paperwork was a second job. The pills made things soft around the edges in a way that felt more like losing than relief. Through all of it, I kept one picture in my head like a saint on the dashboard: my father at the gate, older and softer, holding a sign with my name, maybe hugging me hard enough to bruise. That picture kept me through PT that made my good arm tremble and through the nights I counted ceiling tiles like prayers.

At the airport, the picture tore on a single text. That’s the thing about hope—how quiet it is when it breaks. Your brain doesn’t do thunder; it does a small click.

A week later, in a room that smelled like antiseptic and vanilla lotion someone at the nurses’ station must have gotten for Christmas, my father called and called and called because the direct deposit didn’t land and the mortgage bounced and he needed me now. It was so outlandish it would have been funny if I hadn’t been tethered to a machine that made my blood remember its job. I hung up and stared at the bulletin board where someone had pinned a comic about a cat driving a car. The cat looked like it was doing just fine.

That’s where you might expect me to tell you I blocked his number and the story ends with me finding better people. But Dayton is a small place and stories slip under doors. A local reporter named Kelly showed up with a notebook, earnest eyes, and a pen she actually used. She didn’t treat me like a source to be mined; she treated me like a person telling a thing. I said yes because tired and visible can feel like the same thing once in a while.

The story aired on Channel 7: “Veteran Returns from Iraq, Ignored at Homecoming.” My mug shot from an awards ceremony no one attended. A slow pan of a concourse that looked like every concourse. A sentence: Dayton soldier left alone. If you’ve ever watched the world catch fire from a hospital bed, you know it looks smaller than you’d think. The next morning, my phone buzzed not just with Frank’s calls but with something else: neighbors, old classmates, strangers. “Saw you on the news. You don’t deserve that.” “Whitfield, we got your back.” “I’m bringing a casserole tonight. Don’t argue.”

It’s fashionable to mock casseroles. Don’t. They are an answer in ceramic. The church down the street sent flowers. A veterans group dropped grocery cards and a pamphlet I didn’t throw away for once. Paul, the Uber driver, appeared with a paper bag of apples. He shrugged. “My wife said fruit,” he said. For the first time in my life, people were showing up for me, not for my brother or my father’s standing. Just me.

Meanwhile, my father’s world shrank. At Kroger, people muttered when he walked past the peppers. At the VFW, a man with more mustache than patience said loudly, “Heard you couldn’t drive your daughter home from the airport, Frank. Hell of a thing.” David took heat from his barbecue crew. “Guess ribs are more important than blood,” one man said. David laughed too hard and went quiet. Frank called me again, voice soft with desperation for the first time I can remember. “You shouldn’t have talked to that reporter. You’re making us look bad.”

“They understand perfectly,” I told him. And hung up.

He took it to church, as men like him do. Pastor Jim prayed for veterans by name. Frank left before the benediction. Mom called later, voice tight as hair-pin curls. “Why are you doing this to us?”

“I told the truth,” I said.

“You’ve embarrassed the family.”

“The family embarrassed itself,” I said. That one hurt her. She hung up. I didn’t cry. I stared out the hospital window at a parking lot rimed with ice and felt the click again. Not the click of hope breaking. The click of a lock turning.

Part Two

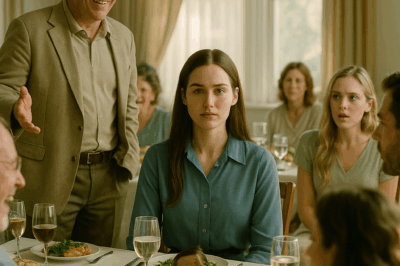

The VFW hall on Keowee Street smells like a hundred potlucks and a thousand cigarettes. It’s the kind of smell that clings to coats even when you wash them. The fundraiser had been planned weeks earlier to buy honor guard uniforms—the kind of quiet need towns still recognize as honorable. By the time I walked through the door under the neon sign, word had shifted the event into something else. Flyers called it “Support Our Soldier.” My name was on the poster. I considered running.

They clapped. Not a polite rustle. A clap that had weight. Mrs. Turner, the neighbor who had once held my hand at nine while my arm swelled and my parents couldn’t be bothered, lifted her chin and waved with the kind of pride I thought I’d stopped needing. Jenkins from Toledo limped down the aisle toward me, sunflower seeds in his pocket, grin wide. He squeezed my shoulder.

“They’re here for you,” he said. “Take the mic.”

I took it. The wooden podium had scratches like a history. “Evening,” I said, voice thin in the speakers at first. “Most of you know me as Frank Whitfield’s daughter. Some just know me as that girl who went off to Iraq. I want to tell you a little about what happened when I came home.”

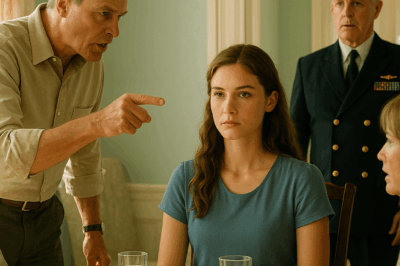

I didn’t name the airport. I didn’t need to. People in Dayton know the layout by heart. “I asked my father to pick me up. He texted back: ‘Your brother’s BBQ is more important.’” A murmur. Heads turned toward the back, where Frank sat in his church blazer like he thought clothing could change a story. “I typed the word I always type—‘Fine’—because that’s what I learned to say. Fine when they left me at the ER. Fine when they left my graduation. Fine when I enlisted and the joke was ‘free college.’”

My hands shook. I held the podium tighter. “A week later, I was in a hospital bed because my pipe broke and the carbon monoxide alarm did its job. Twenty-eight missed calls from my father. Not to ask if I was okay. To ask where my VA check was because the mortgage bounced.”

The sound in the room changed, a living thing. Shame is loud when it moves in a crowd. Frank stood a little, sputtered something about misunderstandings and busy and barbecues that had already been planned. His voice sounded small in a space that had already decided. I didn’t raise mine.

“For thirty years, I asked for nothing but to be seen. The only time I was, it was about money.” I turned to him. “Now you remember me? This town remembers what you chose instead.”

It didn’t feel like courage. It felt like finally breathing. People lined up to shake my hand, to hug me, to press twenty-dollar bills into my palm as if money could fix the small broken rooms in us. Pastor Jim squeezed my hand. “You spoke truth,” he said. “That took courage.”

Jenkins handed me a styrofoam cup of coffee that tasted like the inside of a thermos. “You did good,” he said.

It turns out that a night like that doesn’t solve a life. It does something else: it moves a town’s center of gravity. For weeks after, people stopped me at the library, at the gas station, at Kroger by the oranges. “You’re that Whitfield girl. Good job.” “I remember you from school—you were the quiet one.” “We should’ve done better by you.” The last one was said by a woman who taught me algebra with chalk dust on her sleeves and grace in her eyes. “We should’ve done better by you.” The sentence landed like balm and like a bruise. Yes. And.

I moved into a little place near Fifth Street, close enough to smell coffee from the shop that still plays old country on an actual radio and to walk to the library where Marlene keeps a list of romance novels hidden under the counter for the widowers who pretend they came in for Westerns. The landlord was a Vietnam vet with eyes that had seen more than anyone should. He knocked fifty dollars off my rent and shrugged when I tried to argue. “Service discount,” he said. It didn’t feel like charity. It felt like a hand on my back when I rounded a corner.

I started volunteering with student vets at Wright State, the ones who look fine and aren’t, the ones whose hands shake when they fill out a form, the ones who are tired of telling the same story to offices that make them repeat it until it feels like fiction. We met on Wednesdays in a room with a carpet that had seen better coffee. We talked about insomnia and forms and the weird guilt of feeling like a fraud because your body doesn’t show the places you’ve been. Sometimes they called me “sergeant” out of habit. I never was. It made me smile anyway.

My dad wrote a letter in neat block printing. I never meant to hurt you. Let’s talk. I put it in a drawer. My mother sent a birthday card with a cartoon cake. Love, Mom & Dad. No note inside. I put it on the counter and didn’t feel much. Absence had become a room I knew the layout of.

The family I had now looked more like the people who showed up: Jenkins, who drove down from Toledo with sunflower seeds and a terrible joke; Mrs. Turner, who brought peach cobbler on Sundays and told me stories about her late husband that made me cry in the good way; Paul the Uber driver, who dropped off apples without making it a thing; the students who lined my door with thank-you notes in handwriting that looked like they’d been taught by someone who used a ruler under the line.

One afternoon, standing at my apartment window, I watched the Miami River shiver orange and gold in a sunset that looked like someone had spilled a bucket of paint over the horizon. The tomatoes in my little raised bed had finally set, yellow blossoms turned into small green fists promising more. I thought, I don’t need to be seen by the people who refuse to look. I need to see myself.

Revenge, I decided, wasn’t slammed doors or dramatic speeches. It was quieter. It was buying new sheets with your own money and making the bed on a Wednesday just because you like crisp cotton. It was saying no to a family dinner where you don’t exist. It was telling the truth out loud in a room where lies are comfortable and then washing the coffee pot. It was building a life where you are not a supporting character in your own story.

Frank called less. When he did, it was about logistics. “Can you send—” he’d begin. “No,” I’d say, not unkindly. Ending a cycle doesn’t always require anger; sometimes it just requires a calendar.

He learned the town’s memory was longer than his excuses. VFW men who once nodded at him now studied their cups when he walked in. The neighbor he’d bragged to for years refused his offer to get the grill lit at a block party. “We got it,” the neighbor said. It stung him. I can’t pretend it didn’t make me feel something like vindication.

“Are you happy?” a student asked me in group after I told a smaller version of this story, one with fewer kitchen details. She was twenty-one, tough mouth, soft eyes. She wore an old hoodie with the sleeves pulled down over her hands like the world was drafty.

“I am,” I said. “More than I expected.”

“What changed?” she pressed.

“I stopped waiting for people who weren’t coming,” I said. “And I started feeding the people who showed up.”

She cried, but in the way that made me believe she would sleep that night.

When the tomatoes ripened, I cut one still warm from the sun and ate it over the sink with salt. It tasted like a better summer than I’d had as a kid. My phone buzzed. A number I didn’t know. “Is this Sarah?” a voice asked. “My name is Angela. I’m a friend of your brother’s. I saw the story. I wanted to say—none of that was right. We were at that barbecue. I didn’t know. I’m sorry.”

“Thank you,” I said. It didn’t fix a thing. It also mattered more than she knew.

In August, I drove past Lynen Avenue because sometimes you have to test yourself. The maple was bigger and uglier. The siding had been repainted a beige no one’s heart could love. Frank stood in the yard pretending to look at gutters while actually looking at me. I thought about stopping. I didn’t. I thought about honking. I didn’t. I pressed the gas gently and watched the house in the rearview turn small. There was grief. Not the kind you write poetry about. The kind that lives in the collarbone and makes your breath catch when you laugh too hard.

A year after the hospital, I stood in the VFW again at a different fundraiser. This one was for honor guard uniforms, like the first, but now the room felt different. Frank wasn’t there. David wasn’t there. The MC didn’t introduce me as someone’s daughter. He said my name. He said veteran without the face people make when they think they should admire you but don’t know why. I spoke about mentorship and paperwork and why you should never go to the VA alone if you don’t have to. People clapped politely. No thunder. The kind of applause that comes from people who know clapping isn’t the work.

When I finished, an older man I’d seen a hundred times and never met stopped me. “You gave us all courage,” he said, using the old man us that means more than it says. “Folks think family is blood. You showed it’s protection.”

I drove home by the river. The sunset was less dramatic. Peace always is. I parked. I watered the peppers. I sat on the steps with a glass of water and watched night move in.

My phone buzzed one more time. A text from a number not in my contacts. Saw you on the news a while back. I just got home. No one was at the gate. Can we talk?

“Yeah,” I wrote back. “I’ll meet you at the coffee shop on Fifth. It smells like burned toast and bad country music. You’ll like it.”

If you’re listening and you grew up as a ghost in your own house, if you’ve ever stood at a gate and watched other people’s arms wrap around other people’s shoulders, if you’ve ever typed “fine” when what you meant was a scream—hear me: you are not invisible. Your worth is not measured in who shows up for the person other people want you to be.

Family isn’t always blood. Sometimes it’s the neighbor who drives you to the ER and stays even though the game is on. Sometimes it’s a man with sunflower seeds in his pocket who drives three hours because you need someone in the front row. Sometimes it’s a reporter who asks and then listens. Sometimes it’s a veteran landlord who knocks fifty bucks off the rent and says don’t mention it. Sometimes it’s a whole town that decides the truth matters more than a dad’s pride.

My father skipped my homecoming and called me in a panic when his bills came due. For thirty years, I had answered with “fine.” This time, I didn’t. This time, I spoke. The town heard. He heard too, in the only way he could—through the silence people gave him back.

The revenge I ended up with wasn’t about making him small. It was about making my life big enough that he no longer cast a shadow I had to live in. I built a room where I am seen and brought chairs for other people who thought no one would save them a seat. I planted tomatoes for just me. I signed my own name in my own ledger. I didn’t wait.

If you saw yourself anywhere in this, tell someone. Say it out loud. Not to shame anyone—not even him. To free yourself. That’s what the world is full of for people like us: small keys hidden in pockets we didn’t know had seams. You might have to look. It’s worth it.

And if you’re still standing at the rail in an airport, eyes on the crowd, think of a girl in Dayton who typed “fine” for thirty years and then learned a better word. A girl who built a life where her phone buzzes with need that isn’t hers alone. A girl who finally started calling “home” the place she chose.

That’s the ending I wanted and didn’t know how to write when I got off that plane.

I’m writing it now.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load