My Dad Said I Wasn’t Invited to Christmas — So I Made Him Drown in 20 Turkeys

Part One

My name is Rebecca, and I used to think Christmas was the one time of year when stubbornness softened and old grudges slipped off like coats at the door. We had our rituals—the same tree farm, the same crackling Bing Crosby vinyl spinning on Dad’s old stereo, the same dent in the red-and-green tablecloth where my sister and I once knocked over a candle and scorched December into the fabric forever. We ate the same turkey, too, a bird Dad carved with the pomp of a parade marshal while Mom shuttled bowls of mashed potatoes and green beans like a lunch lady for the angels.

As a kid, I loved those rituals like they were part of my body. As a soldier in the desert, I loved them even more, because they meant home. Christmas letters from Mom would find me halfway across the world, still smelling faintly of her perfume, filled with updates about neighbors and weather and how Dad had already “drafted everyone into gravy duty.” I kept those letters in the chest pocket of my uniform, a soft, secret armor. When the sand got into everything and the sun burned the horizon down to a line, I’d take out a page and read until the smell of pine and wood smoke outmuscled the diesel and dust.

Somewhere after I came home for good, the things that kept me upright started rubbing my dad the wrong way. It wasn’t a dramatic explosion—no door ripped off the hinges, no plates smashed—more like a dozen little skirmishes that left dents in the furniture. He didn’t like that I asked “why” before “okay,” that my independence didn’t clock out when I came back from the base, that the girl he’d expected to say yes had grown into a woman who sometimes said no. He’d rib me about “army talk” when I slipped into mission-mode during holiday logistics, and I’d rib him right back for assigning tasks as if Christmas dinner were a squadron deployment.

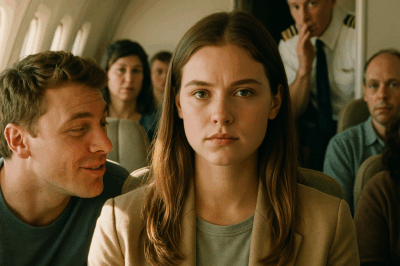

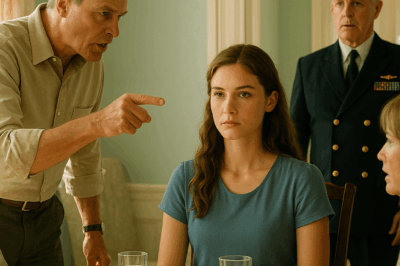

The Christmas before the turkeys, we fought. It started over politics and swerved into money and then folded into questions about what counted as a good daughter. He raised his voice. I raised mine. Mom sat between us at the dining table like a tired referee who’d just discovered the whistle didn’t work anymore. We all put our napkins down too fast. It was ugly and then it was over and then it wasn’t, because fights in families don’t end when the words stop. They hang in the curtains and seep into next week’s phone calls.

Even so, I bought the gifts early the next December—practical, forgiving choices. A new skillet for Mom with a weighty feel and a promise of pancakes; a toolbox for Dad because I thought maybe, if I gave him something he respected, we could meet on a sturdier piece of ground. I imagined the softening. Families fight; families fix it; that was the rule.

Then he called.

“Rebecca,” he said, and the word sounded like an announcement over a loudspeaker. “Don’t bother coming this year. You’re not invited to Christmas.”

The receiver was suddenly hot in my palm. The kitchen went so quiet I could hear the refrigerator hum stepping out of the wall. Outside, the neighborhood was strung up in glitter and good cheer, but inside my apartment the air turned into something I had to swallow. “You can’t be serious,” I managed.

“I’m dead serious,” he said, and hung up.

If you’ve ever had someone take a tradition away from you with a sentence, you know it’s not just about the day. It’s about the version of yourself that day contains, and how quickly that version can be pushed out the back door without a coat. I stood in the kitchen, staring at the stack of wrapped gifts like they were props for a play I’d been cut from. For a while I did what a person does when a thing doesn’t make sense: I paced. I made tea I didn’t drink. I told myself I didn’t care. I told myself I’d endured worse alone: night shifts on deployment where the cold gnawed, funerals in borrowed suits, the aftermath of things you cannot unsee. I told myself a single Christmas outside the fence would not kill me.

But hurt has its own gravity. It pulled every thought down to the same spot, and when I got tired of circling it, something in me sparked.

Not fury, exactly. Not grief, either. A bright, ridiculous little pilot light.

In the army we were taught a dozen ways to respond to disrespect, only one of which was to ignore it. Response did not always mean retaliation; sometimes it meant escalation of kindness, sometimes strategic silence. But it always meant you did not let the other side define the story alone. My father was not the enemy; he was my father. But the sentence he’d fired across my bow—you’re not invited—needed an answer in a language he would recognize.

I didn’t wake up the next morning with a plan. I woke up with the taste of cold coffee on my tongue and the kind of bone-deep ache you get after sleeping bad on purpose. I brewed another pot—strong like we used to on base, the kind that scours the rust off—and sat down with an old green army notebook. In those pages I’d once sketched patrol routes and supply lists; that morning, I drew a turkey.

It was fat and stupid-looking. Then I drew another. By the time the mug was half empty, I had a lineup of birds marching across the paper in little cartoon boots. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, so I did both and wiped my face with the back of my hand. The idea tipped from stupid to genius. If he wouldn’t let me bring a dish, fine. I would bring dinner. I would bring all the dinners.

One frozen turkey would be petty. Two would be a gag. Five would be a headache. But twenty—twenty would be an operation.

I went to the VFW that afternoon—Max, my dog, in the passenger seat, his head out the window like a flag. The hall smelled like spilled beer and ancient fryer oil and the kind of laughter that’s been keeping people alive for decades. Carl, a retired sergeant with a laugh like a chainsaw starting, patted the stool next to him. “You look like you’re scheming,” he said, sliding over.

“Maybe I am,” I said, and I told them. About the phone call. About the sentence that had landed like a door slamming. About the Christmases I’d carried across oceans like talismans, only to be told to drop them now at the curb. The table caught the drift fast—anger nods, sympathy snorts, the understanding that comes from knowing what pride does to love.

“So what are you going to do?” Carl asked, grinning like he already wanted to approve.

“Turkeys,” I said. “I’m thinking turkeys.”

“Turkeys?”

“Twenty.”

The table howled. A woman I’d served with slapped the bar so hard her glass shimmied. “That’s the pettiest, most beautiful thing I’ve heard all year,” she wheezed. “Deploy the birds.”

Carl wiped his eyes. “Run it like an op,” he said. “Recon. Secure supply lines. Stagger the drop. Mission Turkey.”

The name clicked into place like a round into a chamber. Mission Turkey. It made the whole thing feel less like a prank and more like a brief—a series of steps you could follow to get from hurt to resolution. It also gave me cover with myself: this wasn’t childish, it was strategic. And maybe it was both. Maybe the overlap was the point.

I went home, flipped open the notebook, and wrote columns: source, cost per pound, delivery options, schedule. I called Frank at the family grocery store where we’d bought turkeys since I was tall enough to see over the freezer bins, asked how many frozen birds he had on hand, listened to him swear in admiration when I said I needed twenty. “You feeding the entire National Guard?” he asked.

“Something like that,” I said. “Classified.”

He chuckled and promised birds by the pallet. Marlene’s Deliveries answered on the second ring—she’d run a courier service in our town since I was sixteen and trying to get flowers to prom on time, always with a voice like a church bake sale and the logistics of a general. “Sweetheart,” she said when I told her what I wanted, “I’ve delivered everything from puppies to prosthetics, but never turkeys in waves. I’ll need your notes written clear as orders.”

“I’ve got the stationery,” I said.

That afternoon, I wrote twenty of them: COOK IT YOURSELF—the same block letters we’d used on field reports when clarity meant nobody died. I slid each paper into a plastic sleeve because hot kitchens steam and winter is wet. The notes sat in a pile on my kitchen table like little white flags that refused to surrender.

Mom called that evening. The tone in her voice tried to be soft, but the strain was a splinter you couldn’t miss. “Your father—he doesn’t mean everything he says,” she murmured. “He gets… he gets carried away.”

“Then why does he always manage to carry the worst part?” I asked, then regretted it instantly. She sighed and told me he’d come around like he always does and told me not to be alone on Christmas if I could help it and told me she loved me. I told her I loved her too and didn’t say another word about the birds.

The next day I drove to the store to stare down the logistics. The freezer aisle hummed like a low, cold choir. Turkeys sat shoulder to shoulder in frosty plastic—brand names I knew by heart from years of pulling the giblet bag out and laughing even as the cold made my fingers ache. I put a hand on one and imagined twenty of its cousins stacked in Dad’s garage, forming a snowbank of petty stubbornness. A woman pushed her cart past and gave me a look like she couldn’t decide whether to call security or ask for a recipe. I smiled with all my teeth and moved aside.

Back home, I set alarms. Five in the morning. Noon. Five in the evening. Nightfall. Twenty turkeys in four waves, five per wave; if he was going to control the day, he could try doing it while the supply lines kept arriving. I paid Frank. I paid Marlene. I paid for dry ice because frozen birds in boxes will sweat if you don’t treat them like they’re going to cross a desert. I made a list of neighbors whose porches I knew, a backup plan in case a turkey went missing or the delivery truck broke down on County Road 9. I wasn’t about to be undone by someone else’s flat tire.

On Christmas Eve morning, the first box left my sidewalk in the arms of a wiry driver wearing a Santa hat at a tilt. “Special delivery?” he asked.

“Time-sensitive,” I said. “Operation running in waves.”

He gave me a mock salute. “Yes, ma’am.”

I sat by my window with a mug and Max’s warm head on my foot like a sandbag. The city was quiet in the way cities are when everyone is unwrapping and nobody is driving. At 8:30 a.m., my phone rang. Mom’s laughter spilled into the room like a parade. “Rebecca,” she gasped. “Oh, Lord. You should see your father. He’s standing in the driveway with two turkeys under his arms like he’s about to make a citizen’s arrest. He keeps saying ‘What the—’ and never finishing it.”

I could see him. Flannel robe. Hair doing its own thing. First turkey in, second turkey in, third nowhere to put it. “Another box just pulled up,” Mom whispered, and then she started laughing again so hard she forgot to cover the receiver. “He… he’s telling the courier there’s been a mistake. The courier said he follows orders.”

I pressed the phone to my ear and listened to the sound of my mother remembering what it felt like to enjoy her own house.

By noon, there were birds in the garage, birds in the freezer, birds forming a defensive perimeter along the back porch. Mom called after the second wave to report Dad had tried to wedge three into the freezer and cracked a shelf. “He’s begun muttering about logistics,” she said. “I told him I know a woman who can teach him a thing or two.”

Neighbors noticed. Of course they did. They’d lived beside us for years; they knew the cadence of our fights and the songs we played too loud. Mrs. Johnson from next door brought over a casserole and asked whether we were running a turkey drive out of our garage. Little Tommy from across the street shouted, “Mr. Collins, is this a turkey store?” and Dad apparently said, “Go home, Tommy,” without realizing that children don’t do shame the way adults do and only later decided he should feel some.

In the late afternoon, with the sun shoving gold under the cloud cover, the third wave arrived. The wind had teeth. The delivery driver whistled “Deck the Halls.” Dad took the last box with the resigned expression of a man who knows the war is going poorly and cannot switch sides. Mom narrated like a sports announcer: “He tried to hide three behind the lawn mower, Rebecca. A mountain of meat behind a mower, as if the Hendersons wouldn’t notice when they came over to borrow a snow shovel.”

By sundown, five more boxes hit the porch. The notes went with them, sitting on top in their plastic sleeves like labels on ammunition: COOK IT YOURSELF. Dad read one and shook his head hard enough Mom heard it from the kitchen. I sat in my apartment and laughed into my sleeves until Max thumped his tail like a metronome to keep me breathing.

Around nine, my phone lit with Dad’s name. I watched it ring and let it go to voicemail. His voice came through rough and edged, the way a man sounds when his pride has taken a punch and he’s tasting copper. “Rebecca,” he said. “I don’t know what you think you’re doing, but this isn’t funny. You’ve embarrassed me. The whole neighborhood’s talking. Twenty turkeys. Call me back.”

I poured a bourbon, sat by the window, and watched snow fall under the streetlight like tiny parachutes. I didn’t call back.

Christmas morning dawned steel-gray, the kind of winter that makes your breath feel like a secret you can only share in pieces. My phone was crazy with missed calls—twenty-three, then twenty-four. Mom. Dad. My sister, who lives two states away and likes to know where the bodies are buried even when she didn’t have a hand in the funeral arrangements. I answered her first.

“What did you do?” she demanded, not even bothering with hello. “Dad’s been stomping around the driveway with birds under his arms, Rebecca. Mom keeps giggling like she’s been day-drinking eggnog since dawn. He says you’ve ruined Christmas.”

“Ruined?” I said. “Sounds like I made it memorable.”

She laughed—really laughed—and for a moment we were girls again, listening at the stairwell to the grown-ups arguing about politics with the TV too loud. “Honestly,” she said, “if I didn’t hate road trips, I’d be there right now just to watch.”

We hung up. I sat in the silence afterward and felt something complicated settle—vindication, yes. Relief. A little grief. Revenge and love live closer in the body than you’d think.

Mom called again that afternoon. No giggles this time—just a warm, steady hum. “He’s calmer,” she said. “Still grumbling. But quieter. Thoughtful.” She paused, then added, “He hasn’t touched the bourbon.”

We were both quiet for a moment. Out the window, a plow shuddered by. Max sighed in his sleep. “Maybe that was the point,” I said. “Not to humiliate him. To make him think.”

“Maybe,” she said. “And maybe to remind him that you’re yours before you’re his.”

That night, Dad called again. I let it ring twice and picked up.

“You think this is funny?” he asked, no greeting. The words fell into the room like dumbbells.

“Yes,” I said. “I think it’s hilarious.”

He was silent long enough that I thought the line had gone dead. Then he exhaled. “You’ve embarrassed me. Everyone’s talking. Mrs. Johnson brought a casserole. The Hendersons asked if I needed freezer space. Your mother won’t stop… reacting.”

“You told me I wasn’t invited,” I said, doing my best to keep my voice quiet. “What did you expect me to do? Sit on my hands? Wrap presents for strangers? Bake a pie for a ghost?”

He didn’t answer that. I heard the faint clink of ice in a glass and thought, so much for not touching the bourbon. But when he spoke again, the edges had dulled. “I didn’t mean—” He stopped and started over. “I didn’t think you’d go this far.”

“Maybe now you’ll think twice,” I said. “Before you cut me out like I’m a frayed thread you can just snip.”

Silence thickened. He said, almost to himself, “You’re impossible.”

“Maybe.” I let a smile into my voice. “But I’m still your daughter.”

He didn’t say another word, just hung up. I didn’t cry. That surprised me. Instead, I sat in the quiet and felt a small bridge sketch itself across the distance. It wasn’t weight-bearing yet. But it existed.

In the days that followed, the story spread like spilled gravy: church ladies elbowing each other in the pews, dads at the hardware store smirking over boxes of nails, someone posting a photo on the neighborhood Facebook group of my father standing guard in a yard ringed by birds like sandbags. The caption read: Turkey Central. Proceed With Caution. I should have felt guilty. Instead, I kept laughing in grocery aisles at nothing in particular and then catching sight of my face in the freezer door and seeing a woman who had pulled off something with more love in it than malice.

New Year’s came. Mom texted me a photo: Dad in his work boots and an apron, flipping turkey breasts on the grill, steam rising like fog in the cold, a beer in his hand. Underneath it, she wrote: He says he never wants to see another bird again. I caught him sneaking bites when he thought no one was watching. I laughed until I couldn’t see and then left my phone face down for an hour because sometimes joy is too bright to stare at directly.

A week into January, I drove over. The snow on the side of the road had turned into that gray crust that crunches like bad cereal. I pulled into the driveway and saw him before he saw me—shovel in hand, wool cap half sideways, a man who looked like the version of himself I miss from childhood and the version I wish would show up to every conversation now. He didn’t turn away. He didn’t charge at the car. He leaned on the shovel and waited.

I got out, Max leaped from the back seat, and the three of us stood there for a second like a very awkward statue garden.

“You didn’t bring more turkeys, did you?” he asked.

“The supply lines are empty,” I said.

The corner of his mouth twitched, and then—small mercy—his shoulders dropped. “Come inside before we both freeze,” he muttered, and opened the door.

The house smelled like wood smoke and cinnamon and the ghost of turkey that had permanently retired in the curtains. The tree was still up, shedding needles in a carpet that Mom would normally have vacuumed three times by now. She came from the kitchen with flour on her hands and put those hands on my face and said “you’re here” like it cost something to say.

We sat in the living room with our old arguments folded under the cushions. Dad put the shovel by the door and didn’t say anything for a long time. He didn’t apologize. He did say, “You made me look like a fool.” I said, “You made me feel like I didn’t exist.” We held those two truths in the air together and watched them stop fighting.

“I guess I deserved it,” he said finally, staring at his hands.

“We both deserved better,” Mom said, and reached over and touched his arm like she was steadying a ladder.

We sat in the quiet for a while—no Bing Crosby, no TV, just the soft tick of the baseboard heat and Max snoring like a distant truck. It wasn’t forgiveness, not yet. It was a ceasefire with the terms still being negotiated, and for the first time in a long time, that felt like enough.

Part Two

By February, the Great Turkey Siege had settled into the permanent exhibit of our family museum. My sister called it that—the siege—with the kind of relish only a sibling can muster when a legend doesn’t implicate them directly. Cousins joked about bringing sides “just in case Rebecca pulls poultry again.” At church potlucks, people volunteered my dad for anything that involved carving knives and “leadership” in the same sentence, and he grunted and went along with it because sometimes the only way to move through a story is to walk right into its punchline.

I went over on a Tuesday to help Mom clean out the garage freezer that had been drafted into involuntary service. We worked side by side with Ziploc bags and a roll of masking tape, labeling leftovers like we were archiving state secrets. “Turkey tetrazzini,” I wrote on three bags; “turkey soup” on four; “turkey who-knows” on one we agreed to donate to science. We joked about opening a roadside stand: BECKY’S BIRDS — FREE IF YOU LISTEN TO A LECTURE ABOUT PRIDE.

Dad wandered in mid-operation and leaned against the doorway with the theatrical sigh of a man who wants you to notice he’s sighing. “If I see one more bird,” he muttered, “I’m enlisting in the chicken corps.”

It wasn’t actually funny, but it was the exact dumb joke his twenty-seven-year-old version would have made, and I laughed like he’d killed on a late-night show. He gave me a sideways look like maybe he was trying out being delightful and wanted a report back from the field.

It took a few more weeks for anything that could be called a conversation to happen. It happened on a Wednesday morning because conflict rarely checks the calendar for drama. He called while I was at my desk and said, “Are you coming for Sunday dinner?” in a tone that was less invitation than weather report. Still, it was a call.

“Am I invited?” I asked, and made my voice light.

Silence, and then, “Don’t be smart.”

“Then don’t be specific,” I said, and we both let the little barbs land, and then we both, miracle of miracles, tried again.

“Yes,” he said. “Come. Your mother insists. And I…” He cleared his throat. “It’s time.”

Time for what, neither of us said. Time to stop letting a sentence be a house we all have to live in. Time to figure out if we could stand in the same room and not revert to our worst lines. Time to test structural integrity.

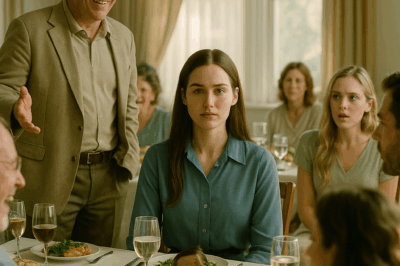

I went. Mom had the roast beef in the oven because any deviation from turkey felt like salvation. Dad tinkered with the stereo and found Bing Crosby like he had to prove he still knew where that record lived. We ate, we pretended we didn’t notice when the conversation swerved toward weather to avoid politics, we watched Max fail at not begging, we washed dishes with our shoulders touching in the small space between sink and counter. Every minute we didn’t blow it up was a minute banked.

After we’d dried the last plate, Dad leaned on the sink and looked out the window at the backyard. “You always got into my tools,” he said, not turning around. “You always wanted to help, made a mess, made me mad.”

“I always wanted to be where you were,” I said, and the sentence hung between us like laundry you don’t bring in because the sun isn’t finished yet.

He didn’t apologize then, either. But he put his hand on the counter and tapped twice like you do when you knock on a closed door and don’t want to startle the person on the other side. It was nothing. It was everything.

We found small ways to practice the truce. I came over on a Saturday to help Mom take down the tree that had gone crispy in the corner like it was auditioning for a fire safety video. Dad and I wrestled the trunk out the front door, leaving a trail of needles that would show up in the carpet until Easter. “You didn’t bring more turkeys,” a neighbor called from across the street, and Dad scowled and then, catching himself, scowled a little less. “She’s on probation,” he called back, and I thought, we are, aren’t we? All of us, under observation in our own home.

He began to tell stories I’d never heard about his own father, a man who believed children were to be arranged, not raised. How Christmas at his house had been a line of cousins on a piano bench and no laughter allowed after eight, how the turkey was a test he never passed—carved wrong, served too cold, too hot, too late. I listened like a daughter and like a soldier and like a woman who’d finally found a translator. It didn’t excuse everything. It explained some of it. Sometimes that is the only bridge you can build in a day.

We did the practical work, too. He admitted the shelf in the freezer was cracked beyond what duct tape could redeem. We drove to the hardware store, grabbed a replacement, argued about the price of stupid plastic in front of a clerk who had already heard the turkey story and winked at me over Dad’s shoulder. On the way out, Dad stopped by the bulletin board where people staple flyers about dog-walking and band practice and missing gloves. Someone had pinned the photo of him in the yard, arms crossed, poultry perimeter intact. Someone had drawn a Santa hat on him and written GOBBLE COMMANDER in sharpie. He stared at it longer than a man needs to stare at a joke. Then he huffed out a laugh he tried to swallow and failed.

“You going to take it down?” I asked.

“Waste of a staple,” he said, and left it there like a trophy.

I told him, once, in a moment when the air felt generous, how it had felt to stand in my kitchen after his call and hear silence ding in my ears like a bell. How insult isn’t just the word you hear but the hours that follow it, and how those hours had needed a thing to fill them that wasn’t bourbon or begging. I told him the turkeys had been ridiculous on purpose because there was no dignity left to preserve, and sometimes you have to laugh your way back to the place where dignity might live again.

He said, after a second, “Well. You did that.”

We were not fixed. He still watched the news like it was a personal insult. I still rolled my eyes in a way that made him catch his breath like he thought they might get stuck that way this time. But we were practicing a motion—reach, pull back, reach again—that I recognized from physical therapy after I messed up my shoulder. It hurt at first. Then it hurt different. Then you could do things you hadn’t been able to do for months.

Spring taught us mercy by degrees. The snow receded, the icicles fell off the gutter in a dramatic suicide, the neighborhood finally ran out of jokes about turkeys and began telling new ones about potholes. One Sunday after church, Mrs. Johnson pressed a hand on my arm and said, “You saved my Christmas,” and it took me a second to realize she meant it. “We haven’t laughed like that in years,” she said. “Laughter makes room for other things.”

I brought a pie to dinner on Mother’s Day—the good kind with a lattice because Dad had always respected precise work—and Dad asked if I would show him how to crimp the edges. He leaned in too close and I swatted his hand away because there are laws in this kitchen and he grinned like he had expected the swat and wanted it anyway.

We never used the words I’m sorry in the combination and order a therapist might recommend. We used pass me that, just a second, I’ll get it, you sit, we’ll see, and they added up to something sturdy enough to stand on.

Sometime in June, we had the yard sale Mom had been threatening to have since 2009. We set up card tables, dragged out boxes of nonsense nobody needed, put price stickers on things people would buy just to have a story to tell about how cheap we were. Dad pulled a turkey roaster out of the garage and put it in the “free” pile. A man in a Titans hat asked if it worked.

“It’s cursed,” Dad said, deadpan. “But it works.”

The man took it anyway. Dad watched him walk away and then turned toward me. “You know,” he said, “I keep thinking about that day. The deliveries. The notes.”

“COOK IT YOURSELF,” I said, and the words took up the space in the air like prayer.

He nodded. “I guess I could have, all along. Thought I was the only one who knew how to do Christmas. You got me there. Twenty times.”

I didn’t try to turn that into a bigger moment. I just handed him a roll of quarters for change and stood in the sun until the back of my neck got hot and the smell of someone else’s hamburgers made us both think about dinner.

By fall, the family text thread had recovered enough for jokes and weather alerts. My sister sent a photo of a turkey-shaped yard ornament and typed, too soon? Dad typed, banished, which for him was practically stand-up comedy. Mom typed, hush, and then, what are we doing for Thanksgiving? and a hundred-year question landed with less weight than I’d feared.

We made a plan. We agreed on volunteer shifts in the morning, a smaller dinner than usual, fewer side dishes, more chairs. We divided the labor like adults and nobody shouted. The day arrived and we pulled it off. Dad carved the turkey with less flourish than usual, like a man who has been humbled by poultry and lives to tell the tale. At the end of the meal, he raised his glass the slightest bit higher than is technically necessary and said, “To being invited,” and everybody clinked and looked at me in a way that would have embarrassed me two years earlier and felt like a benediction now.

On Christmas Eve—the anniversary of the siege—I sat in my apartment with Max snoring and the lights on the tree doing that soft blink that makes it look like the room is breathing. The phone rang. Dad.

“Don’t send birds,” he said. No hello. Same old. New smile in his voice.

“I wasn’t,” I said. “The supply lines are still dry.”

Silence—just the good kind this time, full of things that didn’t need saying. Then: “You coming in the morning?”

“If I’m invited.”

Pause. “You are.”

“Cook it yourself?” I asked.

“Cook it together,” he said, and it was corny and perfect and I let him get away with it.

We ate breakfast under a tree we’d insisted on cutting ourselves because some traditions are worth the trouble. We made eggs and bacon and something Dad called “hash” that was really just last night’s potatoes rebranded. We laughed at nothing—like people who’d discovered the joke is the glue. We turned on Bing Crosby and made it through three songs before Mom switched to Nat King Cole, and Dad didn’t argue, which is how you know a man can change.

Later, as the house filled with the smell of things roasting and simmering, I slipped outside with Max and stood in the yard, hands in my pockets. The sky was that particular winter blue that looks like it might shatter if a kid throws a baseball at it. The neighbors had their porches dressed up like postcards. Somewhere far off a snowblower coughed itself awake. I looked at the spot where, one year earlier, my father had stood among twenty birds and his own stubbornness and thought: revenge can be a meal, but it shouldn’t be the only course.

The turkeys had been funny. They had been petty and deliberate and necessary. They had delivered a message that my arguments had failed to: I am here, and you do not get to erase me. They had made my mother laugh so hard she lost her breath and made my father look at himself with his hands empty. They had broken something open. That mattered more than the humiliation, more than the spectacle, more than the photo on the bulletin board with a Santa hat.

Inside, Dad clanged a pan. Mom shouted, “not that one,” and then laughed at herself. I went back in. There were potatoes to peel. There was gravy to stir. There was a truce to practice until it looked like love.

When people ask me now whether I regret it—twenty birds, the expense, the theater, the neighborhood fame—I tell them the truth: not once. Because revenge was only the opening act. The headliner was the thing that came after—the slow, unglamorous work of changing the story, one Sunday dinner at a time. We didn’t fix the past. We built a hinge into it, and the door started to move.

Maybe your family doesn’t need a poultry parade to remember itself. Maybe yours needs a letter, or a joke, or a line drawn in the sand that says, no further, not like this. I am not encouraging you to buy a freezer full of birds. I am telling you that sometimes, when you’ve been written out of your own life by someone who can’t hear you yet, you have to send a message big enough to echo off the garage door.

On the first anniversary of the siege, Mom wrapped something small for me and slid it across the table with a look that said don’t make fun of me. Inside was a tiny silver charm shaped like a turkey leg on a chain. I laughed so hard I scared Max. Dad rolled his eyes and then—because I think he’d been practicing—said, “Go on, put it on. Let’s see if it brings us luck.”

I clasped it around my neck and it was ridiculous and perfect. Later, when we took the holiday photo, he stood beside me with his hand on my shoulder—the exact pressure he used when I was little and about to step into traffic—and we both looked at the camera like people who had been to war together and come back not as enemies but as survivors with a very particular private joke.

Twenty turkeys did not fix a lifetime. They did not turn a stubborn man into a different species. But they did what a good operation does: they accomplished an objective and made room for the next, larger mission—one that looked less like theater and more like Thursday mornings with coffee and asking, “How’s your shoulder?” and answering, “Better. Yours?”

The neighborhood never forgot. Neither did we. And every time I pass the grocery store freezer and hear the low hum, I smile to myself and think of supply lines and notes in plastic sleeves and a driveway full of birds and the way my mother laughed like a carol at midnight. If you ask me for the moral, I’ll give you two words that no field manual ever printed: Cook it. And then, if you can, do it together.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load