My Dad Said I Was “Just Support Staff” — Then His Pilot Buddy Found Out I Led Delta Echo

Part 1

I’m Colonel Dana Whitaker, forty-two years old, and I’ve spent the last two decades in uniforms most people never see, inside rooms most people never enter.

On paper, I lead Delta Echo, a joint tactical unit specializing in rapid response, intelligence coordination, asset recovery, and the kind of operations that never make it onto the news. In reality, I lead people who live in the gray space between diplomacy and disaster, whose work exists somewhere between a rumor and an after-action report with half the lines blacked out.

It sounds impressive when a stranger says it.

When my father says it—if he ever does—I’m “real good support staff” who “keeps the maps straight.”

Last summer I flew home for one of his barbecues. I hadn’t been back in months. Work had swallowed me whole, and I needed air. The kind that didn’t taste like recycled HVAC in a windowless briefing room.

It was hot enough that the tarmac shimmered when I landed. I wore civilian clothes that still felt like deployment: plain, functional, nothing to catch attention. A duffel bag over my shoulder, my government phone silenced but heavy in my pocket, like a heartbeat I was ignoring.

My parents’ house hadn’t changed. Same faded siding, same oil stain at the edge of the driveway where my father always “meant to power-wash it when things quieted down.” I could hear voices in the backyard as soon as I stepped out of the car. Male laughter, familiar in tone if not in content—pilots telling stories they’d told a hundred times before, each retelling sanding the dangerous parts into something that fit between sips of beer.

Stepping through the sliding glass door felt like crossing a border. One minute I was Colonel Whitaker, Delta Command. The next, I was just Dana, the girl who grew up in the shadow of a retired Air Force engineer who believed in checklists more than conversation.

The backyard was full of folding chairs and people past their prime pretending they weren’t. My father stood by the grill, spatula in hand, wearing an old squadron T-shirt that still fit him like armor. He saw me and his face lit up in a way that always hit me half a second too late, like my body didn’t quite trust it.

“There she is!” he called, raising his voice so the whole backyard could hear. “My daughter. Keeps the folders and flight logs straight. Support staff. Couldn’t run a squadron without girls like her.”

The men around him laughed. The kind of laugh that’s meant to be warm and ends up patronizing by accident.

I smiled like I didn’t hear the words beneath the words. Walked over, shook hands, nodded when they told me their names—“Callsign Rocket,” “Callsign Moose,” “Callsign Bishop”—like we were in a recruiting ad.

“Well, Dana,” one of them said. “Your old man tells us you keep him honest about paperwork. That true?”

“Somebody has to,” I said lightly.

They laughed again. I could feel the edges of my teeth grinding together.

My father slung an arm briefly across my shoulders, a quick, almost awkward touch. “She’s always been organized,” he said proudly. “Straight-A student. Could’ve run the admin shop for half the base if they’d let her. She’s working, what is it, logistics now? Big maps, lots of screens.”

My jaw tightened. I’d briefed strike teams before raids. I’d authorized extractions with enemy drones overhead. I’d watched red dots on a screen and known every one of them was a human being who might not make it home.

“Something like that,” I said.

The moment didn’t explode. It sank.

The men drifted back into their stories. Near-miss landings. Engine fires over the ocean. A cargo door that wouldn’t lock in ‘89. I listened for a while, the way you listen to a language you once knew but don’t speak anymore.

Every now and then someone would glance my way and ask something vague.

“You ever deploy, Dana?”

“A few times,” I’d say.

“Stateside or…?”

“Mostly overseas.”

My father would jump in before I could say anything more. “She’s always been more brains than boots,” he’d say. “Not really the in-the-field type. Great at charting routes, though. Honestly, a godsend to her COs.”

I’d nod and sip my beer and stare at the grill smoke curling into the sky, thinking about people I’d watched board helicopters and not come back.

Support staff, I’d think.

My father didn’t mean it as an insult. That was the problem.

He never had.

Growing up, everything had a right place and a right way. Our shoes lined up by the door. Our dinner at 1800 sharp. Homework done at the dining room table, pens at right angles to the paper. My father measured life in precision and protocol. He loved blueprints because they obeyed him. He loved machines because, if they didn’t, he could take them apart until they did.

He didn’t know what to do with a daughter who didn’t.

I was a quiet kid. Too many books. Too many questions he didn’t think needed answers. When the lawn mower broke when I was ten, I took it apart in the garage because no one else was home and the grass was knee-high. I cleaned the carburetor, realigned a bent cable, and had it humming again by the time he pulled in.

He told the neighbor I’d held the flashlight.

He wasn’t cruel. He wasn’t screaming. It was a thousand small re-writes like that. Each one taking something I’d done and shifting it half an inch to the side, into a category he understood: helpful, not capable. Support, not lead.

Straight As in high school? “Looks good on an admin resume.”

Scholarship to a tech program? “You sure you want to be around that kind of crowd? Might be rough for a girl.”

The first time I said I wanted to join the military, he laughed.

“You’d hate the boots,” he said. “And the yelling. You want to serve, look into admin tracks. Air Force can always use someone to keep the schedules straight.”

So I pushed anyway. Quietly. Steadily. The way I’d always done.

When I brought home my commissioning letter, he nodded like I’d brought home a library card. “Good. Solid work. Benefits’ll be decent,” he said.

He didn’t come to my commissioning ceremony. Said flights were too expensive, hotels were a hassle. “Take pictures,” he added. “Your mom’ll want to see.”

Standing in his backyard now, years later, the past and present folded together in a way that made my chest tight. I’d built a career in rooms he’d never see, doing work he’d never really tried to understand.

And somehow, to him, I was still the girl holding the flashlight.

I escaped to the grill between rounds of small talk, pretending to check the burgers. The heat from the coals made my eyes sting. Or maybe that was something else.

“Hot enough for you?”

The voice came from my left. I turned to see one of the pilots—taller than the others, lean, with that old-school posture that said he’d spent years strapped into a cockpit and never really got out of it. His hair was white at the temples, but his eyes were sharp.

“Colonel James Lell,” he said, offering his hand. “You’re Dana, right?”

I shook it. “I am.”

“Your dad says you’re in logistics,” he said casually. “That can mean a lot of things these days.”

“Depends on the day,” I replied.

His gaze dropped briefly to my wrist. I forgot I was wearing the watch—matte black, nothing flashy, but custom issue. DE-37, small enough that most people would never notice it, distinctive enough that the ones who needed to know, did.

Lell’s eyes narrowed a fraction.

He looked back up at me, expression completely changed. The friendly backyard smile was gone. In its place was something else—recognition layered with something very close to respect.

“You’re with Delta Echo,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

Conversations around us kept going for another half-second. Then, like someone had flipped a switch, they died off. The air got heavier.

My father, halfway through a story about an engine failure over Kansas, trailed off.

I held Lell’s gaze. The old habit kicked in automatically: never confirm more than you have to, never lie if there’s a way around it.

“Yes, sir,” I said quietly. “I am.”

He blinked once. “What’s your billet?” he asked, though his eyes said he already knew.

“Unit lead,” I said. “Joint tactical command.”

He put his beer down on the edge of the grill like his hand didn’t quite trust itself to hold it.

“Colonel,” he said again, and this time the word landed differently. Heavy, deliberate.

Around us, the other men shifted. My father stared at me like he’d just realized the house was built on a fault line.

“How long?” Lell asked.

“Six years,” I said.

He let out a breath that was almost a whistle. “I’ve read your after-action reports,” he said softly. “Well. The parts I was cleared to see. DE-79, DE-81…” He shook his head once. “You’re not ‘support staff.’ You’re the reason those birds lived long enough to land.”

My father cleared his throat. “Delta Echo?” he repeated. “That’s… that’s Intel, isn’t it? Support, right?”

Lell turned to him slowly. “No, Whitaker,” he said. “That’s not support.” He looked back at me. “That’s the unit command everyone prays is on the line when things go sideways.”

The silence that followed was thick enough to chew.

Nobody made a joke. Nobody laughed.

For the first time in my life, my father looked at me and didn’t immediately try to translate me into something smaller.

He looked lost.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t gloat. The part of me that wanted to hurt him the way his words had hurt me sat up and pressed against my ribs, but I kept it caged.

The noise of the barbecue slowly resumed around us, but it never really went back to what it had been.

Because once someone sees the real shape of you, they can’t un-see it.

Part 2

That night, after the last car pulled away and my mother disappeared upstairs, the house felt too big and too quiet at the same time.

I leaned against the kitchen counter, arms folded, the way I had as a teenager when we argued about curfew. Through the doorway, I could see my father at the dining table, elbows on the wood, hands clasped.

It was the posture of a man who’d taken a hit he didn’t know how to classify.

He stared at the grain of the table for so long I started to think he’d fallen asleep sitting up. Then he spoke, voice low.

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

It would have been easier if he’d been angry. If he’d accused me of lying, of keeping secrets, of disrespecting the chain of fatherhood.

But he sounded… hurt. Confused. Like a man who’d discovered the blueprint he’d been working from was wrong.

I looked down at my socked feet against the worn kitchen tiles, the one near the fridge with the crack I used to push toy soldiers through when I was eight.

“You never asked,” I said.

The words came out steadier than I felt. They landed between us like a dropped wrench.

He flinched.

“I always figured you’d… tell me. If it was something big,” he said. “If it mattered.”

There it was, naked and unvarnished. The core of the whole damn thing.

I swallowed. My throat felt raw, like I’d been yelling even though I hadn’t raised my voice all day.

“It did matter,” I said. “It always mattered. You just didn’t hear it.”

He looked up at me then, really looked, and for a second I saw the man who’d lifted me onto his shoulders at air shows when I was five. The one who’d let me hold a model fighter jet and told me about lift and drag like I understood.

Then the years settled back over his shoulders.

“You were always good with details,” he said quietly. “Organized. I thought… I thought that’s where you’d fit best. Where you’d be safe.”

Safe.

I almost laughed. Safe in rooms with no windows listening to men scream over comms. Safe tracing financial trails that led to bombs. Safe watching live footage of people who didn’t know a satellite camera had become their guardian angel.

“What did you think I did, Dad?” I asked. “When I told you I was deployed. When I missed Christmas. When I called you at three a.m. because it was the only time zone that fit.”

He rubbed his thumb along the edge of the table. “I thought you… coordinated. Schedules. Routes. Kept things from getting lost. That’s what you said.”

“I said I coordinated joint operations,” I replied. “You heard clipboards.”

He winced.

“I didn’t know,” he said. “I swear to God, Dana, I didn’t know.”

“That’s the point,” I said. “You never tried to.”

We let the quiet stretch until it started to feel like another person in the room.

He cleared his throat. “Lell… he — he knew who you were.”

“He knew my unit,” I said. “That’s different.”

“He called you Delta Command,” my father said. “I’ve spent my whole life around pilots, around command. You don’t say that lightly.”

I shrugged, because anything else would feel like bragging and that felt wrong.

“We all do our job,” I said.

He shook his head slowly. “I used to read articles about units like that and think, ‘Somewhere there’s some hotshot kid making those calls, and their dad must be proud.’”

His voice cracked on the word proud.

“And I was standing next to you, calling you ‘support staff,’” he said.

There was a part of me that wanted to lift that weight off his shoulders. To say it was fine, that I’d never cared. That my chest hadn’t ached every time he praised the neighbor’s son for making Airborne while treating my promotion to major like a nice bullet point on a resume.

But I’ve spent my career telling people the truth when lies might get them killed.

I didn’t know how to start lying now.

“It hurt,” I said simply. “For a long time.”

He nodded once, sharply, like I’d confirmed a calculation he already suspected was off.

“You know, when you were ten,” he said, “and the lawn mower broke, I told Wilson you held the flashlight. I remember that. I remember his face. He thought it was funny. I thought it was… easier.” He looked at me. “But you fixed it, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” I said.

He exhaled. It sounded like air leaking from an old tire.

“I got it wrong,” he said. “All the way down.”

He didn’t say I’m sorry.

Not that night.

He only asked one more thing before he went to bed.

“Is it too late to fix it?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly.

He nodded like he’d expected that. Then he stood, hesitated like he wanted to say more, and settled for a light squeeze of my shoulder as he passed me.

“You’re… something else, Dana,” he said.

It wasn’t enough. Not for the girl I used to be.

But for the woman I’d become, it was the first brick in a bridge he should have started building years ago.

I didn’t sleep much that night. Old memories shuffled themselves out of storage.

Twenty-three, fresh out of my commissioning ceremony, standing on the deck of a carrier for the first time, lungs full of salt air and possibility. My first assignment: junior signal officer, responsible for communications timing, bandwidth allocation, and the fragile lines that keep operations from collapsing into chaos.

I earned my first commendation that year for streamlining comms during a joint force exercise that nearly turned into a live disaster when a training op bled into real-world airspace.

When I called my father, still buzzing from the debrief, he’d said, “Glad you’re keeping busy. You get that oil leak on your car checked out?”

I remember staring at the endless ocean and feeling my chest cave in, just a little.

At twenty-eight, I coordinated real-time signals intelligence across three allied nations in Europe. I built digital trails that let teams go in at the right time instead of too late. I missed birthdays, weddings, my cousin’s funeral. I made captain somewhere between one crisis and the next.

He didn’t come to that ceremony either. Flights, hotels, hassle. “Send pictures,” he texted. “Looks intense. Stay safe.”

At thirty-two, I was in a secure room with no windows, briefing combat teams on threats fifteen minutes before they kicked down doors in a country I’d never set foot in. I sent him a photo of me in uniform in that briefing room.

“Looks like a lot of computers,” he replied.

By the time Delta Echo tapped me on the shoulder at thirty-six, I’d stopped sending updates. Stopped handing him opportunities to look away.

Delta Echo wasn’t a job you interviewed for. It was a quiet knock after too many nights where your name kept showing up in the right After-Action sections. They watched, they waited, and when they decided you could carry the weight, they handed you more.

The first Delta briefing lasted six hours. Half of it was names and codenames I wasn’t allowed to write down. Half of it was scenarios that started with “If you fail…” and ended with numbers that looked like casualty projections.

We sat in a room with walls that tried too hard to look normal and were asked one question that wasn’t on paper.

Why do you want this?

We went around the room. Some people answered with patriotism. Some with ambition. When it was my turn, I said, “Because I’m good at keeping people alive.”

It wasn’t bragging. It was a promise I’d been making quietly for years.

My father never knew about the night we diverted a convoy three minutes before it would have hit a trip wire buried under a stretch of road the local forces swore had been cleared. He never heard the gratitude in the field commander’s voice when he radioed back that they’d found the charge and nobody had died that day.

He never heard the static-filled call with a field lead pinned behind a collapsed wall, drones overhead, voice steady only because mine was.

“Two meters forward,” I’d said. “Stop. Wait. Three o’clock, twenty steps. Now.”

He’d made it out. Two of his team hadn’t. I still see them on bad nights, small red triangles on a satellite image that winked out mid-transmission.

When my father asked me, a year or two into Delta, what exactly I did now, I’d said, “Joint operations coordination.” It was the safest true answer I could give.

He’d laughed.

“Bet you’re great with maps,” he said. “Military always needs organized girls.”

Organized girls.

I’d changed the subject to his blood pressure medication.

Lying on my childhood bed that night after the barbecue, staring at the ceiling, I realized something I didn’t like.

I’d joined, climbed, and bled for a career partially because I loved it… and partially because I wanted that man downstairs to look at me and see something other than “almost.”

Now he finally had.

And I had no idea what to do with that.

Part 3

Three months after the barbecue, my father had a minor heart scare.

Nothing catastrophic. Angina, his doctor said. Stress, decades of bad diner coffee, stubbornness—pick your poison. They adjusted his meds. Scheduled a follow-up. Told him to lay off the salt.

When my mother called to tell me, her voice walked the line between worry and annoyance.

“He won’t take it seriously,” she said. “Keeps saying he survived worse in ‘84.”

I took leave and flew home for the checkup.

We ended up in the same kitchen, same table, different conversation.

He’d mellowed in the months since the barbecue. Less pronouncements, more questions. Clumsy ones at first.

“How’s work?” he’d ask.

“Busy,” I’d say.

“What does ‘busy’ look like?” he’d ask next, then immediately correct himself. “What can you tell me, I mean.”

I’d give him pieces that were safe. Training rotations. Simulation drills. The promotion board for two of my captains, both of them ten years younger and twice as sharp as I’d been at their age.

“Do you like that part?” he asked. “Promoting people?”

“Yes,” I said. “More than I expected.”

He nodded, as if something clicked for him. “You were always good at seeing things in people,” he said. “Didn’t realize that’s… part of your job now.”

It had always been part of my job. He just finally had language for it.

The night before his checkup, he handed my mother an envelope and said, “Give this to Dana if… well, just give it to her either way.”

I didn’t find out about it until a week later, when I was back on base and knee-deep in a prep cycle for a joint exercise.

The envelope arrived in my office mail bin. Plain. Local postmark. My name written on the front in my father’s uneven block letters.

I waited until my team had cycled out for the day and shut my office door before I opened it.

Inside was his old pilot ring.

I recognized it instantly. Gold, tarnished at the edges, set with a small dark stone. He’d worn it every day when I was a kid, the metal clicking against coffee mugs and steering wheels. It was as much a part of his silhouette as his uniform had been.

He’d stopped wearing it a few years back when arthritis made it too tight to slide over his knuckles. I’d always thought it lived in a jewelry box in my parents’ bedroom, buried under old watches and cufflinks.

The ring sat in my palm, heavier than it looked.

Under it was a single folded sheet of paper.

I got it wrong, the note read.

You didn’t get there because they let you in.

You got there because you belonged.

That was it. No Dear Dana. No Love, Dad. No apology sentence to wrap it in a bow.

Just those three lines.

I stared at the paper until the words blurred, then I sat down hard in my chair.

It’s a strange thing when the story you’ve told yourself about someone shifts. I’d spent years filing my father under “will never understand.” Under “won’t even try.”

This wasn’t a grand, sweeping mea culpa. It wasn’t him falling to his knees and begging forgiveness for a lifetime of underestimation.

It was, however, a man who believed in merit above almost everything else telling his daughter that she belonged where she was.

Not because someone did her a favor.

Because she’d earned it.

I didn’t cry. Not then. Instead, something in my chest that I hadn’t realized was coiled so tightly started to unwind.

I didn’t put the ring on. It wasn’t mine. It never would be in the way it had been his.

But I put it on the corner of my desk, just within my peripheral vision. A small, quiet weight. A marker that the story between us had a new chapter.

Two weeks later, I was in a secure briefing room on the Hill, sitting under bright lights across from a semicircle of lawmakers.

“Colonel Whitaker,” one of them said, “how would you characterize the role of units like Delta Echo in modern conflict?”

I answered calmly. Clearly. I talked about signal-to-noise ratios, about asset deployment, about the ethical weight of remote oversight when you’re the voice in someone’s ear half a world away. Cameras recorded. Staffers scribbled notes.

I wasn’t nervous.

I’d spent my career talking to people who needed the truth quickly. Politicians were just another audience with different insignia.

That night, someone forwarded me an article.

Top 10 Women Changing Military Command Structures.

My name was third.

They’d pulled a photo from a DoD press release—me in uniform, no smile, just the faintest hint of tension at the corners of my eyes.

“A quiet, effective commander redefining leadership from the inside out,” the caption read.

I read it twice. Not out of disbelief. Out of a desire to feel it fully, to let those words belong to me instead of bouncing off the old armor I’d built.

Then, on impulse, I printed it.

A week later, I went to the cemetery.

We’d buried my father three months after his heart scare. It hadn’t killed him, not then, but it had been the first stone on a slide. Stroke. Complications. A hospital bed where a man who’d once jogged five miles before breakfast struggled to move his left hand.

He’d died on a Tuesday morning in his sleep, my mother sitting in a plastic chair by the window, a game show re-run flickering on mute.

I’d given the eulogy. I’d talked about the version of him the world knew: engineer, pilot, problem solver. I’d left out the years of near-sightedness about his own daughter. It didn’t feel like the place to settle old debts.

The grass over his grave was still new, flattened in lines where the sod squares hadn’t fully knit together.

The stone was simple: his name, rank, dates. No flourish.

I stood there for a while without saying anything. The printed article folded in my pocket. The ring warm against my fingers.

“I got your note,” I said eventually. “You still write like an engineer, you know that? Minimal words. Maximum impact.”

The wind moved through the trees. Somewhere in the distance, a lawnmower hummed.

“I’m training new leads now,” I told him. “Two of them are twenty-nine and terrifyingly competent. One of my former analysts runs cyber for Western Command. When they brief, they don’t apologize for being in the room.”

I thought about how he used to introduce me: She keeps the maps straight. Good admin.

“People ask what I do,” I said. “I tell them I lead.”

Saying it out loud felt like walking through a door I hadn’t noticed was there.

I took the ring out of my pocket and set it on top of the stone for a moment.

“I’m keeping this,” I said. “You don’t get it back. That’s not how this works.”

I picked it up again and slipped it into my pocket.

Legacy isn’t about what you leave in a will. It’s about what you build or break in the people who survive you.

My father broke things in me. Confidence. Trust. The belief that being good at something meant people would see it.

He also, unintentionally, built things.

Stubbornness. Precision. A refusal to accept “good enough” when lives were on the line.

I left the cemetery with the ring in my pocket and a clarity I hadn’t had before.

I hadn’t spent twenty years fighting to be seen by one man.

I’d spent twenty years becoming someone I could see clearly when I looked in the mirror.

Part 4

Command is a strange kind of loneliness.

You spend your days surrounded by people, your nights reading reports written by other people, your mornings in meetings with more people. But there’s a line you don’t cross. A space between you and everyone else that exists because, at some point, you might have to send them somewhere they don’t come back from.

I started thinking about that more as I got older.

Maybe it was my father’s death. Maybe it was watching younger officers step into roles I used to live in, moving with a confidence that was half training, half ignorance of just how bad things could get.

Either way, something shifted.

I stopped thinking of myself as someone fighting to be taken seriously and started thinking of myself as someone responsible for making sure the next generation never had to fight for basic respect in the first place.

The first time I saw Captain Morales shut down a condescending brigade commander twice her age in a briefing, I felt a rush of pride that surprised me.

He’d cut her off mid-sentence with a “Listen, sweetheart, I’ve been doing this since you were in diapers—”

She’d let him finish, then said, “Yes, sir, and in that time the threat landscape has shifted from analog to digital. With respect, my diapers don’t invalidate my data. If you want your people home, you’ll follow the route changes on slide seven.”

The room had gone quiet.

I didn’t have to say anything. She’d handled it perfectly.

Afterward, I pulled her aside.

“That was risky,” I said.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “But it was necessary.”

I nodded. “It was correct,” I said. “Just don’t get too addicted to it. Pick your battles. Save your ammo for the fights that matter.”

She smiled. “Learned from the best, ma’am.”

That night, I sat at my desk, the pilot ring catching the lamplight. I thought about my father somewhere in the ether and wondered what he’d think if he could see this briefing room now—women at the front, men leaning forward to take notes.

He would probably be surprised at first. Then, if his last note to me was any indication, he’d recalibrate. Adjust his understanding, however belatedly.

In one of our last conversations before he died, he’d said, “I spent my whole life trusting the system. The rank structure. The idea that if someone made it into a room, they deserved to be there.”

He’d stared at the hospital wall for a long moment.

“I just never thought to apply that to you,” he’d said. “That’s on me.”

There’s a wordless relief that comes when someone you love stops pretending they were right all along.

It doesn’t erase anything.

But it gives you permission to stop trying to prove a point that doesn’t need proving anymore.

A year after the congressional hearing, I got an email from a young lieutenant, subject line: Request for Mentoring.

Ma’am,

My name is Lt. Sarah Polk. I’m with 3rd Signals. I watched your testimony before the committee last year.

I’ve heard rumors about Delta Echo since I was a cadet. I don’t want gossip. I want to learn.

I’m good at patterns. I think I could be better with the right guidance.

Could we talk?

I met her in a coffee shop just outside the base.

She was twenty-six, sharp-eyed, jittery in the way people are when their brains move faster than their mouths.

“You’re already where you need to be,” I told her after she walked me through her work. “The rest is timing and staying alive long enough to matter.”

She laughed, then sobered. “How did you know you were… enough?” she asked. “Like… not just a supporting piece. The one making calls.”

I thought about my father’s backyard. The way his introduction had shrunk me without him even realizing it. The way Colonel Lell’s recognition had thrown all of that into sharp relief.

“You don’t know,” I said. “Not at first. You just keep doing the work. There will always be someone willing to see you as less than what you are. Sometimes they share your last name. Sometimes they share your rank. You don’t fight every one of them. You don’t have time.”

“So what do you do?” she asked.

“You pick the voice that gets to define you,” I said. “Make sure it’s not the one that’s most disappointed or the loudest. Make sure it’s the one that knows what the job takes.”

She nodded slowly, like she was filing that away.

As she left, she glanced down at my hand.

“Nice ring,” she said.

I looked at it—the old gold band now hooked on a simple chain around my neck, tucked under my shirt.

“Remnant from a previous generation,” I said. “I’m just trying to use it better.”

Part 5

The older I get, the more I understand that most wars are fought in places no one writes about.

Sometimes that place is a narrow road in a country whose name your average citizen mispronounces. Sometimes it’s a secure server, a digital battlefield where code does what bullets used to.

And sometimes it’s a backyard, next to a grill, with a father who has you pegged as “just support staff” because he never learned how to update his mental map.

A year after I mentored Lt. Polk, another article came out. This one wasn’t a listicle. It was a long-form piece in a Sunday magazine about “The Quiet Architects of Modern War.”

They interviewed me on background, no rank, no unit name. Just “a senior officer in a joint tactical command.”

The writer asked me, “What do you wish people understood about your job?”

I thought about it long after the interview ended. The answer they printed was sanitized, high-level. The answer in my head was something else.

I wish people understood that “support” isn’t a lesser word. It’s a load-bearing one. But I also wish they understood that women don’t automatically belong there just because it’s tidy, just because it feels safer than imagining us in command.

On the anniversary of my father’s death, I went back to his grave.

The grass had finally rooted, green and unremarkable. Someone had left a small flag. My mother, probably. Or one of the neighbors who still told stories about “Whitaker and that landing in ‘82.”

I sat on the low stone bench nearby and pulled the ring out from under my collar, rolling it between my fingers.

“If it helps,” I said quietly, “I stopped trying to prove you wrong.”

The wind stirred. A plane hummed high overhead, invisible behind the clouds.

“I know who I am,” I said. “Whether anyone else gets it or not.”

Emma—my goddaughter, named not after anyone in my family but after a woman I’d once watched stand up in an ops center and correct a colonel twice her size—would be starting ROTC next year.

She’d texted me a screenshot of her acceptance letter with a string of exclamation points.

They want me, she’d written.

Of course they do, I’d replied. You belong there.

I smiled now, thinking about that.

Maybe that’s the real legacy of all of this. Not the missions nobody will ever read about. Not the committee hearings or the articles or the commendations that get buried in boxes when you change stations.

Maybe it’s the fact that when she walks into a room in uniform, she won’t hesitate when someone asks what she does.

She’ll say, “I lead.”

And no one who matters will question it.

As for me, I’ll keep doing what I’ve always done.

I’ll sit in rooms most people never see, wearing a uniform most people don’t understand, making calls that keep strangers alive. I’ll mentor the ones who come after me. I’ll argue for better structures, better recognition, not because I need it now, but because they shouldn’t have to drag their fathers’ expectations behind them like dead weight.

Every once in a while, when I’m alone in my office and the world outside is quiet, I’ll look at the ring on my desk or feel its weight against my collarbone.

I’ll remember a backyard full of old pilots, a careless introduction, and a single sharp voice cutting through with recognition.

You’re not support. You’re command.

And I’ll remember my father’s last written words to me.

You didn’t get there because they let you in.

You got there because you belonged.

In the end, that’s all any of us are really trying to do.

Find the place we belong.

Stand there.

And refuse to let anyone—family, friend, or stranger with a narrow view—reduce us to anything less than what we’ve earned.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

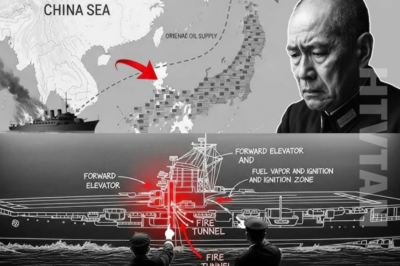

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load