My Dad pointed a GUN at me and said “Sign the Property papers or else!” I Just Smiled. He Had No Idea

Part One

The click was small, like a fingernail against glass, but it made the room huge. Every line in the house that my mother kept polished—the mantel, the picture frames, the glass coffee table—shone hard under the afternoon light as if each surface had been waiting for a reflected gun.

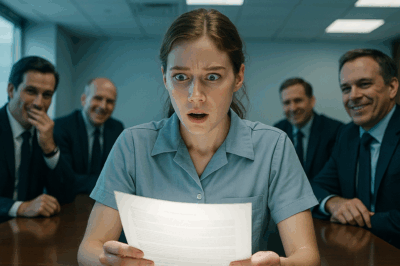

“Sign the damn papers, Alex.” My father’s voice vibrated the glass top so the stack of documents quivered. He shoved them toward me again, his knuckles white around the pistol, his shoulders squared like a man who’d decided long ago that threats could be part of a conversation. “You think you can keep what doesn’t belong to you? You’re nothing without us. Nothing.”

The air smelled like furniture polish and fear. I could feel my pulse in my gums. I kept my hands in sight. “It’s my property, too,” I said, slower than my heart wanted. “Grandpa left it to me, and you know—”

My mother’s laugh slid out of the kitchen doorway, sharp enough to peel bark. She set her wineglass down as if she’d been waiting for a line. “Grandpa left you nothing,” she said. “You were an accident, Alex. A stain we’ve been trying to scrub for twenty-five years.”

Madison, right on cue, wandered in like she’d paid extra for her entrance, silk swishing at her ankles, blood-red nails busy on her phone. She didn’t look up. “Don’t be dramatic,” she said to the air. “You can’t handle money. We’re just setting things right.”

“You mean stealing it?” The words were out before I thought about how words look next to guns.

My father’s nostrils flared. The barrel rose and found the space between my eyes with a calmness that made bile climb my throat. “One more word and you’ll regret ever opening your mouth.”

Fear makes people fold or harden. A smile that never helped me and always infuriated him slid up from someplace old. I saw it hit him. His finger tightened almost imperceptibly. “What the hell are you smiling for?”

“Because.” My voice surprised me by not shaking. “You think you’ve cornered me.” I lifted my chin just enough to meet the gun like it was the least important thing in the room. “But you’re standing on a cliff and you don’t even know it yet.”

“Bluff,” Madison smirked, eyes still on her screen. “He doesn’t have the guts.”

A muscle in Dad’s jaw twitched. He slammed the butt of the gun onto the table; the glass trembled and one corner of the top-page signature block tore. “Last warning, Alex. Sign.”

The paper looked like a map of our family pressed flat with a weight. The top page: Quitclaim Deed. The second: Assignment of development rights. The third: something notarized that pretended I wasn’t in the room. Behind them I could see Grandpa’s workshop in my head—the way light fell through the slats, dust in the beams, the smell of apples from the orchard out back when we opened the big door to let the air and bees in. I uncapped the pen he’d pushed at me. His grin twitched wider. My mother leaned forward as if her eyes could push ink.

I let the tip hover. Then I dropped the pen.

“No.” I didn’t raise my voice. “Not today.”

“Shoot him and get it over with,” Madison said, and that was the line that made something in my head switch from endure to enact.

“Fine,” I said, and set the pen neatly on the table like I was done with a check at a diner. “Take your shot, Dad. Go ahead. But remember this. Whatever power you think you’re holding is hanging by a thread.”

I stared at him until the room felt like a balancing scale and then picked up my bag from the hall chair. The door opened easier than it should have. The air outside bit at my cheeks. Cold tasted cleaner than polish.

In my apartment that night I lay on my back and watched the ceiling fan carve circles. The place smelled like coffee because that’s what I made when I didn’t know how to sit still. My ribs still remembered a kick from a month before, another “discussion” about my “attitude.” But it wasn’t pain that kept me awake. It was cataloguing.

Madison, in college, “borrowing” Grandma June’s rings to sell for a weekend in Cabo. Dad’s whisper deals with the board when I was supposed to be asleep. Mom saying things like We took you in when what she meant was You owe us breath for breath. And Grandpa, the man who taught me to sand wood until the grain felt like satin, who saw value in old planks and stubborn saplings, who kept his eyes kind even when everyone else in the house sharpened theirs.

The chest he left me had always been more than a chest. They thought it was sentimental. It was documentation disguised as nostalgia: ledgers, maps with pencil-sketched boundaries, receipts with notes in his neat handwriting, a will copy so old it smelled like the workshop.

Beneath the papers lay an envelope that carried his handwriting and my name and a piece of him I hadn’t known I still needed.

Alex, the letter said. If you’re reading this, it means they’ve come for what’s yours. Don’t fight them with anger. Fight them with patience. The land is protected, but so is the will. Play it smart. Watch them fall on their own swords.

He had tucked it under a diagram of the trust he named “Blue Thread” for the vein in our wrists and the river that ran at the far end of the orchard. The language made my eyes blur on the first pass and sharpen on the second. The land wasn’t in my father’s name. It wasn’t in mine either. It sat inside a plain, unadvertised entity whose sole beneficiary of distributions was me. Any transfer of title required the trustee’s concurrence. The trustee wasn’t my father. It was Grandpa’s old friend, a retired judge who liked whittling birds on his porch and had a laugh like a motorboat.

The county records office clerk recognized my face from a high school civics project and slid land books across the counter with boredom. The chain of title told a story of persistence: Great-Granddad had bought sixty acres in 1948 for a number that wouldn’t buy a garden shed now. Zoning maps in a dusty binder showed how those sixty acres had become more interesting to developers this year than they had been in seventy. There were permits—provisional, none final. There were letters of intent—conditional, all of them leaning on an assumption: that I would sign.

My father had been betting on fear. He hadn’t met my patience.

I learned the trust allowed me to remove the successor trustee if he proved conflicted. Grandpa had thought of that, too. The retired judge was stubborn but not immortal; the successor my father had named in a private writing had his name on it. One filing later, with a sealed affidavit and the judge’s signature carved like a little bird, the successor was not my father anymore; it was a bank that didn’t drink whiskey with anyone.

It wasn’t enough to protect. I wanted them to feel what they’d made me feel in every room where my name tasted like apology.

Madison’s engagement party date arrived in my inbox because her publicist sister-in-law had made the RSVP portal a press release. I bought a suit that fit me the way Grandpa would’ve asked—does it let you move?—and I showed up under lights that warmed everything without hiding anything.

She pulled me aside with nails like knives. “Why are you here?”

“To congratulate you.” I smiled the way wolves do in fairy tales when they’ve already rewritten the ending.

They thought the party was social gravity. I knew it was a guest list of reporters and donors and councilmembers who had stopped being careful about what they said in front of me.

A week later, a woman from the business desk whose cubicle I’d slept under during finals when our dorm flooded ran a front-page story: Lane Family Scrutiny: Offshore Accounts, Frozen Trust, and a Troubled Orchard. She had my file of wire transfers—funneled to a Cayman account labeled “Madison Foundation”—copies of invoices with padded “consulting fees,” and a notarized copy of the Blue Thread Trust that looked like a knife slid under a door.

The IRS doesn’t kick in doors with TV’s drama, but it freezes accounts with a brutal courtesy. My parents woke up to balances that had turned into zeros with asterisks and a phone that would not stop ringing.

I didn’t answer my father. Seventeen missed calls, then nine, then one. Silence was an answer he’d never given me; it made him hoarse with rage.

When he did reach me—via an email that said nothing except COME HOME in caps—I went, because patience is not the same as avoidance.

They were smaller in their big house than I remembered them. Paper in drifts. Madison’s picture frames facedown as if modesty had arrived too late. My mother’s hair looked like a decision rather than a style.

“What have you done?” my father demanded, each word a nail thrown at my shoes.

“Nothing,” I said, setting the trust under his hand like a calm volcano. “Grandpa did it. I just let the truth out.”

He stared at his father’s signature long enough for the blood to leave his face. His eyes found mine and something I hadn’t expected flashed there—the memory that he had once been a boy who had stood in a workshop and watched his own father sand a board until it gleamed.

“Next time you point a gun at me,” I said softly, “make sure you’re not standing on a cliff first.”

I left as quietly as I had come. Patience isn’t dramatic. It’s relentless.

Part Two

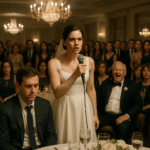

Madison didn’t cancel the wedding because Madison didn’t cancel anything. You could peel the wallpaper off her life and she’d declare it textured. The Crestfield estate’s glass walls made the city look like a prize in a box. Gold runners down the aisle, flowers like a harvest festival, chairs filled with every person who had fed on my parents’ gravity and gotten a little fat.

Her vows started with “forever” because Madison liked words that taste like frosting. When the second “I do” reached for its echo, the venue screens—the ones meant for slideshows of her baby pictures—flickered awake.

There are moments when a room is a lung. This one inhaled. Wire transfers bloomed ten feet high: dates, amounts, destination accounts. The “Madison Foundation” looked terrible under that light. A PDF of a returned check stamped INSUFFICIENT FUNDS scrolled by like a Bible verse in reverse. Someone whispered, “Oh, my God,” and someone else said, “He’s going to be sick.”

“Turn it off!” my father roared, lurching from his row. Security stepped into the aisle and didn’t reach for him. They had my letter from three weeks earlier in their file cabinet: Should any presentation systems be used to display third-party materials, know that the contents have been vetted for accuracy. Please direct complaints to counsel.

Madison grabbed her fiancé’s sleeve with nails that had probably cost more than my computer. “It’s fake,” she told him. “This is a setup.”

His mother, a woman whose jewelry always looked borrowed from a museum, leaned in and said something into his ear that made his mouth go thin. He stepped back, and when she reached for him again, he didn’t offer his hand.

It would have been enough to stop there, to let humiliation eat the cake while the guests filmed the slices. But Grandpa had taught me that rot is not cured by airing once. You keep the windows open.

The land story had been the battle. The next part was the war.

The Blue Thread Trust did not merely shelter acreage; it included the old manufacturing permits tied to the property, the ones my father had described to would-be partners over bourbon as “ancient magic.” He’d staked half his new deals on them. Those deals assumed I’d sign consents like a grateful child. The trust instrument allowed me to revoke those consents with two signatures: mine and the trustee’s. The retired judge had brought a fountain pen.

By the following Monday morning, the development’s scaffolding stood like a rib cage with no lungs. Contractors who had accepted handshake promises phoned my father from the site with voices like thunderheads. Investors called the board. The board called a vote. The vote made my father an emeritus in a way that meant “don’t come back.”

When power leaves a man who has always stood on it like a porch, he flails. He threatened me with court. The trust’s lawyer wrote back in complete sentences that sounded like door latches: Mr. Lane has no standing. He tried moral arguments; I replied with photographs of ledgers. He tried pity; I sent him Grandpa’s note: Don’t fight them with anger.

My patience wasn’t saintly. It was architectural. Patience is how you place a beam so the weight will carry without creaking.

I RSVP’d yes to the city’s zoning commission meeting and no comment to a reporter who caught me outside and asked if revenge tasted like apples. “It tastes like hot coffee on a porch at six a.m.,” I said. “It tastes like not jumping every time a door slams.”

The day the letters went out to donors—Your contribution has been returned; we apologize for any breach of trust—the women who had once worn my mother’s compliments like shawls held each other and did not call her. The men who had once told their sons that Frank Lane was what a man looked like stared at spreadsheets and recalculated what masculinity might mean. That wasn’t my doing, not directly. That was just what a room does when you stop pretending the smell isn’t there.

And the orchard? People had argued about it for years—condos, a golf academy, a parking lot shaped like a tree as if that counted. The trust let me choose no to all of it. I chose a park. We named it Marrow Grove because Grandpa used to say, “Family is supposed to be the marrow of your bones, not the rot under your skin,” and because children love a word that sounds like pirate treasure.

We left the old workshop bisected like a cross-section, half wall down so visitors could see the bones. We planted a row of Baldwin apples because Grandpa had sworn they were crime to bake and sin to eat fresh. We built a community table under the biggest oak and stenciled bring what you can, take what you need on the underside of the plank so people found it by accident and understood it by instinct. The neighborhood showed up with folding chairs, colanders. Kids christened the first hill with a cardboard box that somebody insisted was a sled. The first scraped knee bled perfectly normal human red and got a Band-Aid with astronauts.

The day my parents slowed their older model sedan under the new stone arch and read MARROW GROVE out loud with their faces, I was sitting at the picnic table where Grandpa had planned birdhouses in the margins of ledgers. My mother’s window rolled down halfway. Her hair was set to travel. “You turned our land into this,” she spat, as if laughter were vandalism.

“It was never your land,” I said, because that sentence had waited years in my throat. “And this was never about you.”

Behind them, a little girl shrieked as she reached the bottom of the hill on a strip of cardboard and fell into the grass laughing. The mother who rushed to her wore a T-shirt that said, in permanent marker, ask me about free lunches. The paper cups on the table sweated into rings that looked like planets.

Their car idled a beat and then moved on.

People talk about revenge like it’s a meal—cold, hot, served. Mine was a slow-cooker recipe with ingredients that tasted like taxes and minutes in waiting rooms, signatures and silence. It didn’t fix everything. It didn’t make me the child my mother would have loved if I’d been born a mirror. It did not rewrite Madison into a good sister. It didn’t even stop the old late-night anxiety from sometimes pressing my chest like a book I couldn’t close. It did do this: it made the gun a story rather than a future. It made my father’s threats thin and my mother’s music less catchy. It made spaces where kids learned that adults can apologize and should.

The last phone call I answered from my father arrived on a Tuesday afternoon in July just as the sprinkler caught the sun and flung a halo over the grass like a joke. “I want to meet,” he said without preface.

“No,” I said. “But I’ll listen.”

He cleared his throat in a way I recognized from when he used to practice speeches in the bathroom. “I was a good provider,” he said, like a man reciting a definition.

“You were a good accumulator,” I said. “Provision is different.”

He started a sentence that had the bones of I’m sorry and didn’t make it to the verb. I didn’t hand him a bridge. That’s not cruelty, though my mother would have named it so. That’s boundary, which is a word that once felt like a fence and now feels like a frame.

On the first anniversary of the day he’d pointed the gun at me, I walked into the house with the couch and the coffee table and the pictures in their frames. The gun, thank God, was gone. My father’s hand shook halfway to mine and then decided to make itself a fist around nothing. My mother looked older than the mirrors in her bathroom had allowed.

“Go ahead,” she said finally, when silence had made anything else expensive. “Say what you came to say.”

“I didn’t come to say anything,” I replied. “I came so you can see me not afraid in this room.”

She laughed once, high and brief. “You always were good at performance.”

“Projection,” I corrected. “And patience.”

Madison was not there. She’d posted a story that morning of a plane wing and a caption that read something like hustle and heart, and I had felt nothing except the relief of not having to swallow any more explanations about why she deserved the best slice.

The land behind their house—behind what had been their house—was loud with children. The noise came through even double-paned glass. My father turned toward it like a man who regrets not learning a language because it sounds pretty from far away.

I left, as I had arrived, with my jaw unclenched.

Before summer ended, I had the Blue Thread Trust amended with a clause Grandpa would’ve grinned at: the next trustee was not a person but a committee of neighbors who had baked pies and painted signs and brought extension cords for community nights when the projector declared movie across the lawn. If the trust outlived me, the land belonged to people who would know how to keep it kind. That was the point. Not to clutch. To give.

Weeks later, I ran into the retired judge at the farmer’s market standing in front of a stall of tomatoes that looked like a painter had spilled sunset. He tipped his hat. “Your granddad would be loud about that park,” he said. “Which is to say, he’d sit quiet and grin until somebody asked.”

“I think he already knows,” I said, surprising myself by not crying into a pile of Cherokee Purples.

At home that afternoon, I unlocked the chest with the habit my hands had learned when other things in the house locked on me. The envelope with Grandpa’s letter still smelled like apple wood and pencil shavings. I read it again because sometimes the brain needs the same sentence more than once: Don’t fight them with anger. Fight them with patience.

Outside, the park laughed. Inside, the house didn’t hold its breath anymore.

You want an ending? Fine. Here it is, clean:

My father never pointed a gun at me again. My mother never burned my dress because I wore my grandfather’s flannel to holidays that didn’t require costumes. Madison still posted. Sometimes we scrolled on purpose to remind ourselves how strong the urge can be to tell a better story than the truth. We told the truth anyway.

The orchard bloomed. The workshop stayed open on one side like a book. Kids nailed birdhouses crooked, and the birds didn’t file complaints. A man who had been sober for nine months handed out lemonade at the community table and said, “This counts.” A woman whose pride once kept her from letting anyone know her fridge was empty took a bag of greens and left a note under a rock that read, I’ll bring tomatoes when the first check lands. Thank you for now.

That’s power. Not a gun. Not a signature wrung from a child with a threat. Power that multiplies when you hand it over. Power that smells like fresh-cut grass and paperwork filed so neatly it makes the world hum.

I still smile sometimes the way I did that afternoon with the barrel eye-to-eye. It still makes certain people angry. But now it’s not a bluff. It’s a memory of a cliff I didn’t fall from because a man who sanded boards and wrote careful letters taught me how to build a bridge while other people were busy measuring how far I could be pushed.

He had no idea? No. He had no idea I would choose this ending when he pressed a pen into my palm and a gun into the air. And that’s the best part: he never gets to write another page of this story. I do.

END!

News

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… CH2

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… …

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

End of content

No more pages to load