My Dad Kicked Me Out Over a Secret, 13 Years Later, He Knocked On My Door and…

Part I — The Knock

There was a knock at my door. Just three taps. Measured, deliberate—neither urgent nor uncertain—yet the sound stopped me cold. I was in the kitchen cutting apples for Jonah’s after-school snack. The knife paused mid-slice. I looked at the clock. 6:13 p.m. The street outside was quiet—no deliveries, no neighbors expected, no scheduled visits.

Behind me, Jonah called from the living room. “Mom, you want me to get it?”

I wiped my hands on a dish towel, my heart suddenly hammering. “No,” I said—sharper than I meant. “I’ve got it.”

Only six steps separated the kitchen from the door, but I felt every one. Through the peephole I saw a man I hadn’t seen in thirteen years. Older, thinner, more bent than I remembered. A cane in his right hand. A look on his face I couldn’t read. But I knew that profile. I’d seen it in my nightmares and—worse—in Jonah’s cheekbones.

I opened the door.

He looked up at me and then past me to Jonah, who stood barefoot in the hallway holding his violin, hair still mussed from his bike helmet, eyes quiet and bright. My father’s eyes widened. He didn’t say a word—just stared at the boy he’d never met, at the face he’d once turned away from before it ever came into the world.

In that moment I knew he hadn’t come for me. He had come for the secret I’d carried all these years.

Part II — The House I Left

I was born in Eugene, Oregon, a small-town kind of place where everyone knows your face, your father’s job, and what church pew your family sits in on Sunday. My father, Grant Hartwell, owned Hartwell Timberworks—the kind of business where men shook hands hard and passed it down from father to son. He was a deacon at St. Mark’s and a man who believed in work, order, and obedience—in that order. My mother, Margaret, made lists. Grocery lists, prayer lists, lists of who brought what casserole to the church potluck. She loved us in the quiet, structured way of someone who’d never been taught how to comfort—only how to manage.

And then there was Aaron—my older sister with perfect hair, perfect GPA, perfect purity ring. While she was away touring colleges and giving testimonies at youth retreats, I was just there. I wasn’t rebellious. I wasn’t loud. I just didn’t fit the mold they pressed around me.

At seventeen, I met the person who taught me stillness could be a kind of courage. His name was Matteo Ruiz. He wasn’t from our church. He wasn’t from our side of town. His parents ran a small flower shop off River Street. He tutored after school and played piano at his uncle’s restaurant on weekends. But what I remember most was the quiet around him—not shyness, not emptiness—just a stillness that made you feel safe.

We met in senior civics. By spring, we were taking long walks down the Willamette after school. By summer, we were planning a future that didn’t involve Eugene or timber or pews. Matteo had earned a full scholarship to the University of Washington for architecture. I’d been accepted to a design program in Portland. We talked about renting a studio apartment, splitting grocery bills, hanging pothos vines in a sun-struck window, learning the names of cheeses that weren’t cheddar. Ordinary dreams, but they shone like distant, promised lights.

Life did what it sometimes does to the young—it swerved. Just after graduation, Matteo was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy, a heart condition he’d never known he had. The news hit like a landslide. One week he jogged with me at the park. The next he fainted in his kitchen, knocking a bowl of oranges off the counter. He was put on a transplant list. Doctors said—maybe a year, maybe less.

The conversation shifted from next semester to what if I’m not there? From plans to legacy. And the truth no one in my family ever knew: my pregnancy wasn’t a mistake. It was a goodbye gift. A promise. A way to keep him alive—even if his heart couldn’t hold on. We decided together on that small, defiant act against inevitability. I planned to tell my parents. Not right away, not in the chaos of hospital visits and transplant tests. I wanted to wait until things were calmer, until I could bring them something besides fear. I imagined bringing them the sonogram and Matteo’s tremoring hand, imagined the lace runner on the dining table, imagined that if they saw grief stamped across his face they’d understand.

I never got the chance.

Part III — The Exile

It was a Saturday in late October. I came home from the hospital to a house so still it felt like an accusation. My mother sat in the living room holding a folded tissue, dabbing her lips like she’d been crying but wouldn’t allow herself to smudge. My father stood near the window with his back to me. Between them, on the coffee table, lay the pregnancy test I’d wrapped in paper and hidden in my desk drawer—evidence at a trial I hadn’t agreed to attend.

“Sit,” my father said—not shouted, just flat, like a sentence.

I sat. Before I could speak he turned. “Who is he?”

“It’s Matteo.”

“That boy,” he snapped. “That Ruiz kid.”

I nodded.

“Does he even have papers?”

“He was born here.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

I opened my mouth to tell him about the diagnosis, the transplant list, the choice Matteo and I had made—love threaded through fear—but my father raised a hand and cut through it all.

“You will fix this,” he said, slow and cruel, “or you will leave this house tonight.”

I looked at my mother, hoping for a crack in the wall. “We only ever wanted the best for you,” she whispered—like prayer through a locked door.

Then came the betrayal that cut deeper than the rest. My sister stepped into the room, my sketchbook in her hands—the one I’d tucked the ultrasound inside. “You shouldn’t have lied,” Aaron said. “I found it by accident. I had to tell them.” She said it like virtue, not choice.

“You had to,” I repeated, and my voice sounded like I’d swallowed glass.

“You’ve shamed this family,” my father roared. “You think carrying a bastard child honors God? You walk out that door with this stain and you’re no longer my daughter.”

I stood on shaking legs, hands ice cold. “You stopped being my father,” I said, “the moment my child became a sin to you.”

I left. No suitcase. No plan. Just a girl with a heartbeat inside her and a home behind her that had never really seen her at all.

Part IV — The Desert Years

I disappeared without a sound. No dramatic exits. No slammed doors. No social media rants. Just silence and the road.

The first night I slept behind the old Albertsons on Eighth Street, curled in the back seat of my car, windows cracked, the driver’s hoodie balled beneath my head. I kept one hand on my stomach, just enough of a bump now to remind me I wasn’t alone. By day I walked the strip malls asking for work. Two coffee shops laughed and told me to come back after the baby. A gym finally gave me part-time janitorial shifts—ten fifty an hour to bleach away sweat and gossip in the locker rooms at night. It was something.

I learned which gas stations didn’t mind if you loitered, which diners would refill a water cup if you looked clean enough, which parking lots had cameras but no security patrol. I moved like a ghost through the town I’d once called home. I avoided Main Street, avoided anyone who might know my last name. I didn’t want pity. I wanted air. I wanted time to turn into someone who could carry this child without breaking.

Week three, I fainted in the gym’s staff break room. I’d skipped breakfast again. I woke to someone holding an ice pack to my neck.

“Lily Hartwell?” a woman asked, peering down.

“Yes.”

“I thought I recognized you. I used to teach you art.”

“Ms. Dunley?” I blinked—disoriented, embarrassed, and holding back tears.

She didn’t ask where my parents were. She didn’t ask why I was mopping floors seven months pregnant. She just said, “You’re not sleeping in your car tonight. Come on. I have a guest room and too many quilts.”

In her spare room I sobbed harder than I had in months. The mattress was firm, the sheets smelled like lavender, and above the bed hung a watercolor of an oak tree that bent in the wind but didn’t break. She brewed chamomile and let me talk—or not. She became my first anchor, guiding me toward a clinic for prenatal visits, helping me enroll in a GED course, teaching me to apply for food assistance without shame.

She never tried to fix me. She just saw me. And for the first time since Matteo, I didn’t feel erased.

Matteo’s decline was quick and lingering at once—days of hope that felt like lies, nights of fear that felt like truth. I held his hand while the monitors traced the betrayal in his chest. He tried to joke—said architects draw lines so people don’t fall. “I thought I’d draw our life,” he whispered. “I guess I get to draw one line that matters. You take it, Lily. Walk it farther than I can.”

He died in late November, rain drumming against the hospital windows, a nurse’s soft shoe squeak in the hall. I pressed my cheek to his knuckles until they cooled. The silence after the machines stopped was a kind of deafness I wouldn’t wish on anyone.

I gave birth two weeks later.

Part V — Jonah

He came just after dawn on a Tuesday, wailing like someone who understood the world already—six pounds one ounce, a full head of dark hair, his father’s long lashes. I held him and said, “Your dad would have loved you. You look just like him when you’re mad.”

We stayed at the hospital for two days. Ms. Dunley never left my side. She brought a pale blue blanket she’d crocheted and a stuffed owl from her classroom. My family didn’t come. No flowers. No phone call. Not even a name in the visitor log. I wasn’t surprised, but surprise isn’t required for heartbreak.

The first weeks were a blur of midnight feedings and quiet crying—his sometimes, mine mostly. There were mornings I sat on the nursery floor, back against the wall, just staring at the bassinet and wondering if I was enough. No income, no partner, no family—just me and this tiny soul who depended on me for everything. I loved him fiercely. But love doesn’t cancel exhaustion or fear or the sinking suspicion that maybe they’d been right about me all along.

Three weeks in, I wrote a letter to my parents. Short. Careful. I enclosed a photo of Jonah swaddled in the blue blanket, eyes wide, fists curled like he was already fighting to make room in this world. On the back I wrote: “Your grandson, Jonah Ruiz Hartwell. Born December 12. He’s healthy. He’s strong. He deserves to be known.”

I mailed it without a return address. Just a thread thrown into the dark.

Three weeks passed. Nothing came back.

I told myself I wasn’t expecting anything. I told myself I was strong, that we were fine, that we didn’t need them. I kept telling myself until the lie felt heavier than the truth. They had chosen silence—and that choice echoed louder than any rejection.

Jonah turned one month old with just the two of us and a cupcake we didn’t eat. I lit a candle, held him close, and whispered, “You’re still here. I’m still here. Maybe that’s enough.”

Part VI — The Climb

I passed my GED six months after Jonah was born. It wasn’t easy. I studied between feedings, memorized math formulas while he napped on my chest. Ms. Dunley quizzed me over breakfast—her coffee untouched as she explained fractions for the third time. When the envelope came with my scores, I cried. Not because I doubted I could do it, but because it was the first time in over a year that something official said, You’re still moving.

Jonah learned to crawl on the same thin rug where I filled out job applications. He babbled “ba” and smacked the floor like it had given him offense. By two, I’d enrolled in community college for digital design. I’d always loved sketching shapes and fonts. As a kid I invented cereal boxes and movie posters just to see if I could trick my eye into believing they were real. Now I was learning to turn that into a life.

I worked nights cleaning offices and weekends at a secondhand bookstore. My body ached. My mind felt alive. The first time a coffee shop paid me seventy-five dollars to design a logo, I stared at the check before depositing it. I used the money to buy Jonah new shoes and a box of real art markers. Not the crumbling kind. The good ones.

By the time I finished my associate’s degree, I had a handful of freelance clients. A friend offered me a desk in her co-working space—a sunlit room with plants that actually lived and a whiteboard stacked with ideas. Within a year I filed papers for my business: Hartwell Design Studio. Not for the name I came from, but for the name I rebuilt.

Jonah started preschool. He loved puzzles, gears, anything he could build and dismantle. At night I’d find him lining crayons in color order, humming. He had his father’s calm and focus. Every time I watched him sleep, I knew Matteo would have been proud. We didn’t have much, but we had rhythm. Work, school, home. Laughter. It wasn’t the life my father wanted for me. It was the life I’d chosen, and earned.

Part VII — The Segment

The call came from the community center. They were hosting a Women Who Lead event and wanted to feature small business owners who’d overcome adversity. A friend from the co-working space had nominated me. I almost said no. But something stubborn in me—maybe for Jonah, maybe for the girl who slept behind the Albertsons—said yes.

The crew filmed me at my desk, stylus tapping on glass while Jonah read in the corner. I talked about design, about starting over, about the power of stubborn hope. I didn’t mention my family. I didn’t say Matteo’s name or narrate the years that broke me. The segment aired on local TV, then made its way to Facebook, pinging around town the way gossip likes to wear the clothes of inspiration.

A week later, an email landed in my inbox.

Subject: I saw you.

It was from Aaron.

I read it three times. Her words were concise, careful—like a person testing thin ice. She said I looked strong. She wrote that Jonah looked like Matteo “and it hurt to see.” She said our parents had watched it too. Our dad had a heart scare last year. He talked about me more than I’d think. They wanted to meet Jonah, if I’d consider it.

Not once did she write I’m sorry. Not once did she ask how we’d survived. But something in the way she wrote it hurt to see told me that finally—finally—they had actually seen.

That night I sat on the kitchen floor, back pressed to the fridge, Jonah coloring beside me. He looked up when the silence went long.

“What’s wrong, Mom?”

“Someone from the past just knocked,” I said, “and I’m deciding whether to open the door.”

Part VIII — The Visit

They arrived on a Sunday. I’d agreed only after three weeks of quiet emails setting boundaries I wasn’t sure they’d honor. No sleepovers. No photos posted online. No pretending nothing happened.

They pulled into the driveway just after noon in a silver sedan with out-of-state plates and the same nervous energy that had tensed every childhood Sunday drive. From behind the curtain I saw them. My father, thinner, leaning on a cane. My mother, stiff-backed, gray hair pulled tight. Aaron standing a little apart, arms crossed—the same controlled calm she’d always worn like a badge and a shield.

Jonah stood beside me, violin case in hand. “Do I call him Grandpa?” he asked.

“Not yet,” I said. “Just be yourself.”

I opened the door before they could knock. We stood there, four adults and one child, unsure which word went first. My father broke the stalemate—not with speech, but with breath. He exhaled sharply when he saw Jonah. His eyes didn’t move for a long time, locked on the boy standing tall and quiet—the boy whose face belonged unmistakably to Matteo.

“This is Jonah,” I said. “He’s thirteen.”

Jonah stepped forward, offering his hand the way I’d taught him. “Nice to meet you. I play violin.”

My father reached out, tentative, like the air was fragile. When their hands met I saw the tremor—not of age, but regret.

My mother spoke next, voice trembling. “You kept his name.”

“I kept everything,” I replied.

I led them into the living room where the mantle held a timeline: Jonah’s first day of school, first piano recital, science fair ribbon. In the center, a black-and-white photo of Matteo at seventeen, smiling in a suit too big for him. My father’s eyes landed there. His mouth opened, then closed. He stood straighter, as if the cane refused to bear witness to what came next.

“We didn’t know,” he said at last.

“You didn’t ask,” I answered.

Jonah lifted his violin and began to play. A slow, spare melody, notes placed like stones across a river. He’d written it himself and called it “Found.” No one spoke—not because there was nothing to say, but because the sound of what had been lost filled the room, drowning apology.

When the song faded, Jonah tucked the violin away and left us there. He didn’t need to stay. He’d already said what mattered.

“You said you didn’t know,” I began. “So let me tell you.”

I told them about the diagnosis, about the transplant list, about those last blue-faced nights. I told them about the decision Matteo and I made—love braided with grief, fear braided with hope. I told them about fainting in the gym, about the back seat of my car, about giving birth without a single family name on the visitor’s sheet. About the photo I’d mailed—about the void that followed.

No one interrupted. My father’s fingers knotted on the cane handle. My mother cried silently, tissue crumpled and damp. When I finished, Aaron whispered, “I didn’t know it was that bad.”

“You didn’t ask,” I said again—without heat this time, just the weight of a fact.

My father cleared his throat. When he spoke, his voice was gravel. “I thought I was protecting the family. I thought I was doing the right thing.”

“You protected an image,” I said, “not a daughter.”

Silence, and then—softer—“I was wrong.”

I believed him—not because the words were eloquent, but because they cost him to say.

My mother reached for my hand and I let her fingers settle on my knuckles. “I kept the photo,” she whispered. “The one you sent. It’s still in my drawer. I looked at it every Christmas.”

It should have made me feel better. Instead it made something old and tired inside me ache. Sometimes memory without presence hurts worse than forgetting.

“I’m not here to punish you,” I said. “But if you want a place in Jonah’s life, it comes with conditions.”

“Anything,” my father said. The word sounded like a man who had run out of other forms of control.

“You show up. You don’t make him feel like a mistake. And you never, ever try to rewrite what happened.”

They both nodded—solemn as vows.

“He deserves the truth,” I said.

“So do you,” my mother replied. “We failed you. We will carry that.”

I didn’t smile. I didn’t offer forgiveness. But I didn’t send them away. Sometimes healing starts with simply staying in the room after the truth has been spoken.

Part IX — The Space Between

What happens after the dramatic scene is not drama. It’s logistics. It’s schedules and awkwardness and the boring, holy work of consistency.

They started small. Saturday lunches once a month in a neutral place, a diner where the pie was always suspiciously perfect. My father learned to listen to Jonah talk about string quartets and physics. My mother learned the names of his friends. Jonah learned to keep a weather eye on his own heart.

At first, my parents followed every rule. They brought no lessons, only presence. They asked for no photos, only permission. They kept their opinions like coins in their pockets, unsent. It was strange how quickly habit tried to reassert itself—my father slipping into advice, my mother into agenda—but each time they caught the slide and climbed back to the level place.

Three months in, my father invited Jonah to visit the lumber yard—just a tour, he promised. “We keep a shop cat now,” he said, almost embarrassed. “He chases the sawdust.”

I went along. The place smelled like childhood: sap, oil, coffee forgotten on a workbench. Men who’d known my father thirty years nodded at me, their faces arranging themselves into whichever expression they thought safest. On a wall near the office, the company’s founder stared out from a gilt frame. My father stood beneath it, cane planted like an exclamation.

“This is where you wanted me,” I said softly.

He looked at the floor. “Yes.”

“I’m where I want to be.”

He looked up—eyes old and wet—and nodded.

Jonah found the cat, a gray tom with one torn ear. He crouched and held out a hand. The cat accepted—cautious but hopeful. I thought, maybe this is what we’re all doing here: letting something skittish approach, not making any sudden moves.

The first real test came on a Wednesday in May. Jonah called from school, voice thinned with pain. “Mom, my stomach—bad.” By the time I reached the office he was gray and sweating. The ER dose of morphine didn’t touch it. Appendicitis, the surgeon said—quick prep, we’re going in.

Surgery is only routine until it’s your child. In the waiting room I shook in a way I hadn’t since the hospital with Matteo. That same sterile smell. That same false art on the wall—sailboats nobody wanted. My phone buzzed. It was Aaron.

“Dad’s here,” she said. “We’re in the lobby.”

I hesitated, then told the nurse to let them back.

They sat with me through three hours that bent time like heat. My father held a cup he didn’t drink. My mother counted quietly to five and back down. When the surgeon came out and said “He’s fine,” my father’s breath came out in a broke-back sound I’d never heard from him. It was not relief. It was permission to grieve for thirteen years, compressed into a single exhale.

In the recovery room Jonah looked small and brave. He blinked at the tubes and smiled crookedly. “Hey,” he said to my parents—young and old and filled with kindness. “I’m okay.”

I watched my father reach for his hand, not as if he were entitled to it but as if it were a gift. I watched my mother learn to stand at the foot of the bed and not tidy his blankets. Minor miracles don’t trend. They change a room.

Part X — The Confession

Summer arrived with the smell of cut grass and the anxious joy of a hundred graduations. My clients increased. Jonah practiced for a youth orchestra placement. My parents, to their credit, didn’t miss a single concert. They learned to clap at the right times, to stay late to say “You did well” instead of “You could have done better.” They learned to let their language be blessing instead of instruction.

One evening, after a rehearsal, Aaron lingered on my stoop. The porch light carved small moons in her eyes. “Can I… talk?”

“Okay.”

She stared at the azalea like it might answer for her. “That night,” she said without preface, “I didn’t find the ultrasound by accident. I was looking.”

I didn’t say anything. She went on.

“I was jealous. You had a plan. You had a person who made you brave. I had a closet full of clothes that still had tags. I kept thinking if I told them first—if I was the righteous daughter—maybe I’d get to keep my life the way I wanted it.”

“And did you?”

“No,” she said. “I got a husband who checks our bank balance every time I buy bread. I got… a lot of Sundays.”

We stood with the moths dizzily baiting death against the porch light. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m sorry I wanted to be right more than I wanted to be kind.”

“Thank you,” I said. It didn’t undo anything. But naming a wrong is a way of opening a gate.

“Do you hate me?”

“I don’t,” I said—surprised to realize it was true. “But there’s a version of my life that didn’t happen because of you. Some nights, I hate that.”

She nodded. “Me, too.”

We stood there not touching, and not needing to. The night felt like a room with a window open.

Part XI — The Table

It was my father’s idea to host Thanksgiving at my house. The suggestion came out clumsy and earnest. “If you’ll have us,” he added, hat in his hands like a man asking for employment.

I agreed because saying yes is sometimes the only way to find out what you’re made of. We cooked together, awkward and hilarious. My mother measured nutmeg with a ruler. Jonah basted the turkey like it was a violin lesson—exact and focused. My father chopped onions on a board he’d brought—old maple curved by use.

We ate at the table I’d saved for months to buy. No lace runner. No glass fruit. Just plates, gratitude, and the kind of silence that isn’t empty. Halfway through the meal my father cleared his throat.

“I sold the company,” he said.

I looked up, stunned. “What? When?”

“Last spring,” he said. “To the employees. ESOP. It’s theirs now. I stayed on the board. But it’s not mine to lord over.”

I stared at him—at this man who had once used that company like a scepter. “Why?”

He looked at Jonah and then at me. “I don’t want to be remembered for what I owned,” he said. “I want to be remembered for what I kept.”

People imagine forgiveness is a drumroll—trumpets, a tear falling in slow motion. Mine was a small, practical thing. I passed him the cranberry sauce first. He took it with hands that didn’t quite hide their shaking.

After dessert, Jonah played. Not “Found,” not anything solemn. He played a bright, weather-clean melody he called “Table.” When he finished, my father stood slower than he had to, walked to my son, and pressed the back of his fingers to Jonah’s cheek in that old European gesture that feels like a benediction. “Thank you,” he said.

“Grandpa,” Jonah said, testing the word like a musician tests a new bow. “You’re welcome.”

Part XII — The Last Knock

My father’s health wavered through winter. There were good days, when he walked the block with the cane like it was a companion. There were bad days, when the air seemed heavier and he counted under his breath to keep it moving. He visited weekly, Jonah teaching him the rules of chess, my father correcting him about nothing except how thoroughly to enjoy a win.

One evening in February, I found a small envelope under my door. Inside was a check made out to Hartwell Design Studio—not obscene, not patronizing. Attached was a note in my father’s careful block print: For the girl who slept behind the grocery store. So she can keep not sleeping there.

I called him—ready to scold, ready to argue. By the time he answered, I only managed, “Thank you.”

“It’s yours,” he said. “No strings.”

“Dad,” I said, the word odd and easy in my mouth, “I do fine.”

“I know,” he said. “Let me do this one.”

There are gifts you accept because the giver needs to give. I deposited it and bought three things: a new laptop that didn’t freeze when I breathed on it, braces for Jonah’s stubborn canines, and a maple cutting board to replace the warped plastic one in my kitchen.

Spring brought blossoms like suds on the cherry trees and, with them, a fever that wouldn’t break. We sat with him in a room that smelled like antiseptic and realized this time there would be no easy surgery. I held his hand—this man who had once banished me and then knocked on my door—and told him the truth he deserved.

“You hurt me,” I said. “You said I wasn’t your daughter.”

“I did,” he whispered. “And you were.”

“You failed me.”

“I did,” he said. “And then I learned.”

“You were wrong.”

“I know,” he said. “And I am sorry.”

Sometimes the only ceremony grief needs is candor. We didn’t recite. We didn’t compose. We told the story of what had happened and who we were now. He made me promise three things: to keep the cutting board oiled, to let Jonah choose his own work, and to play “Table” at his funeral.

He died at dawn—like Jonah had been born—with the same rain tapping the same rhythm on the windows. My mother slept with her head on his arm. Aaron stood rigid, daring tears to negotiate. I closed his eyes and thought of that first knock, thirteen years too late and right on time.

Part XIII — And…

We buried him on a hill that looked down at the river. Men he’d employed carried him; men he’d once intimidated cried without shame. The minister spoke about strength. Aaron spoke about the good years. My mother read a Psalm in a voice that frayed on the edges and mended itself mid-word. I walked to the small lectern and looked out at the faces of a town that had known our name longer than I had been alive.

“I am my father’s daughter,” I said. “And I am the woman he could not imagine. He built with timber. I build with color and stubbornness and Tuesday nights. He taught me how to sand a board smooth. I taught him how to sit in a room after the truth has been spoken and stay.”

I nodded to Jonah. He lifted the violin and played “Table.” The melody ran clean as water over stone, and in it I heard everything that had broken and everything that had held.

After the burial, after the casseroles, after the last awkward hug, I went home and stood in my kitchen. The cutting board waited on the counter—new maple gleaming with oil. I washed an apple and sliced it, the knife moving sure and quiet.

There was a knock at my door. Three taps. Measured, deliberate. Again I felt the old pulse, the old past. I opened it to find the mailman, smiling, holding a parcel.

“Package for Ms. Hartwell,” he said. “Looks important.”

It was from a law office in town. Inside, a letter: my father had left one final gift. Not money. Not a stake in the company. Something else. Tucked in the envelope was a key and a deed to the little storefront on River Street where Matteo’s parents had once kept lilies in buckets and roses in coolers that sighed every time the door opened.

My father’s note was short.

For the life you drew when we didn’t see it. Fill it with what you love. Let light in.

The space had been empty for years. I stood in its dusty doorway a week later, Jonah at my side, sunlight spilling across scuffed floors. I could already see it—the front half a studio with tall white walls and big tables, a corner where kids could learn to draw logos for the futures they wanted, shelves for books about type and color and courage. In the back, a small room with a couch for a mother who had to sit and breathe before she told a story that might break her open so it could heal.

Jonah walked to the front window and traced a square in the air. “We should hang plants,” he said. “Pothos. They like light and neglect.”

I laughed. “We won’t neglect them.”

He set his violin case on the counter and turned. “Mom,” he said—half boy, half man, all heart—“you let him in.”

I nodded. “I did.”

“And?”

“And I let him stay as long as he told the truth,” I said. “He learned. So did I.”

We painted the walls that weekend—Jonah whistling, me crying sometimes when I lost track of which layer belonged to which year. Ms. Dunley brought quilts for the couch and triangle sandwiches in wax paper. My mother arrived with a plant she was terrified to kill. Aaron came with a cardboard box filled with pictures I hadn’t seen since I was seventeen—me on a school field trip, Matteo at the piano, my father at a lake, sleeves rolled, holding a trout that looked offended by the whole endeavor.

We hung the sign last: Hartwell & Light. Underneath, smaller letters: design, stories, Saturdays. People came. Kids leaned over tablets to draw their versions of the world. A woman my age cried quietly in the back room and then left smiling at nothing. A retired carpenter stopped by and whittled a pencil holder from scrap he’d kept in his truck for reasons he couldn’t name.

On the day we opened, I sliced apples on the maple board, and Jonah played “Found” and then “Table” and then something new I didn’t yet have a word for. The door kept swinging on its oiled hinges. A town that had once known only one version of my story now walked in and found there were more.

What my father did to me at seventeen—kicking me out over a secret—split my life into before and after. Thirteen years later, when he knocked, I learned something nobody had taught me: sometimes the door we’re most afraid to open hides not a monster but a mirror. He didn’t come for me that night. He came for the secret I’d carried all those years, yes—but he also came for the chance to become a man who could love the person I had become.

So when people ask—because they do, in whispers and without—“What happened when your dad knocked?”

I say, “I let him in. We told the truth. We built a table where there used to be a trial. And when it was time for him to go, we walked him home the way he should have walked me—together, holding what mattered between us.”

It isn’t tidy. It isn’t triumph. It is a life. My son’s laugh in the front room. My mother’s plant miraculously still alive. My sister’s text messages about nothing important. The maple board, oiled and gleaming. The door, unlocked during business hours.

And the knock—now just a sound that means someone is here, asking to be let in, hoping there is light.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

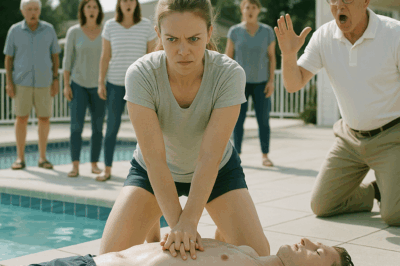

HOA President Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Expected What Happened Next

HOA President Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Expected What Happened Next Part One: Welcome to Sunny Meadows I…

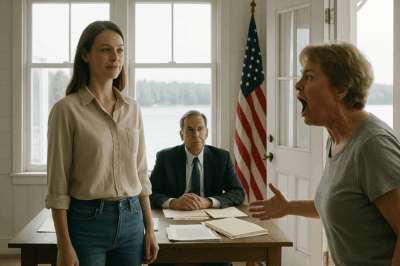

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

End of content

No more pages to load