My dad beat me with a crowbar because I shielded my son from mom — “Let her hit the boy.” Mom laughed, “This is what you get for breeding trash.” But I made sure they were the ones begging next

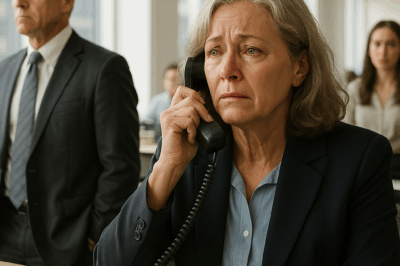

Part 1

The first strike landed on my shoulder with a blunt, stunning force. The second caught my ribs and turned my breath into a tangle of stitches. I didn’t move. I was the wall between my son and the hand raised over him.

“Let her hit the boy,” my father barked behind me, voice dense with the kind of fury that pretends to be authority. Metal slid in his palm—an ugly scrape—and then a flash of iron arced into view. A crowbar. My mother’s laugh threaded the air, thin and cold. “This is what you get for breeding trash.”

On the third swing, his grip slipped. The crowbar glanced off me and clattered to the tile, a sharp, impossible sound—like a bell rung in a church that never blessed us. My son whimpered into my shirt and I gathered him closer. I didn’t cry. I didn’t plead. I looked at the two people who had taught me as a child that love kept a house together, and I memorized their faces. Because this wasn’t the night they broke me. It was the night I began carefully, quietly, breaking them.

It hadn’t always been blood between us. Once, when the world was small enough to fit inside a living room, my father could fix anything that clicked or rattled. He had a toolbox that smelled like machine oil and winter air; he let me hand him the flathead screwdriver like it was a baton and we were conducting a symphony. My mother made chicken soup when I had a fever and tucked me in with a kiss that felt like safety. They were strict—curfews that came with clocks—and sometimes sharp with words, but I translated it as care because a child needs the shape of love to be simple.

Cracks showed up after my son was born. To them he wasn’t a child; he was leverage. They critiqued how I held him, how I fed him, how I soothed him. “You’re soft,” my father said. “He’ll never be strong like this.” “Stop coddling. You’ll ruin him,” my mother added, voice flat, the way a person might remark on the weather. It took me too long to notice that what had been rules for me had become weapons for us both.

The comments escalated in the way cruelty likes to move: sideways until it finds a stair and then down fast. A slap to a table to make my son jump. A hand closing around my upper arm with the command to “look at me when I’m speaking.” A hissed opinion about his father—who had left without looking back—that hung like a fog in the kitchen. I kept my distance. I took the long road around their house and learned to answer the phone only when I had witnesses—coworkers, crowds, my own echo.

I only walked into their home that night because my sister called and said Mom had been “in a mood.” A vague thing, that. Enough to make you wonder if you were paranoid for hearing the alarm underneath. I strapped my son into the car seat, promised myself I’d be in and out, no coffee, no lingering conversation that spiraled into old traps.

Their front door was propped open with a shoe. The smell of bleach sat unsaid in the air. I heard voices, and then I heard the voice that makes every parent move—my son’s, small and confused.

I came around the corner to see my mother towering over him, her right hand poised, palm open. She wasn’t a woman in that moment; she was a posture. I didn’t think. I stepped between them, and my father’s shadow filled the frame of the hallway like a storm front. Metal flashed.

The rest came in pieces: the dull thud of steel against bone; my son’s cheek pressed to my chest; my mother’s lips curling around the words she liked to use when she wanted to press a bruise into your belief about yourself—“breeding trash.” The crowbar falling. Silence hanging like a breath held too long.

They waited for me to collapse. I didn’t. I picked up my son with one arm and my keys with the other and left without a word. My shoulder bloomed into purple that night. The next morning a nurse wrapped my ribs while my son tracked my movements as if I might evaporate when he blinked. He didn’t ask questions; children learn early what silence means.

By the time the pain resolved into a measurable shape, the heat inside me had cooled into something sharper than rage. Not vengeance. Precision.

Step one was evidence. I took photos of the bruises when the morning light showed the edges clearly. I asked the urgent care doctor to document everything. I copied all of it, kept the originals in a sealed envelope, and put the copies on a drive that lived under the bathroom sink in an old shampoo bottle—because some habits of hiding keep you alive until they aren’t needed. I found a lawyer whose portfolio said what I needed to hear without the kindness of a smile: assault, custody, restraining orders, the legal alphabet of survival.

Step two was patterns. Cruelty leaks through walls if you listen long enough. I sat with neighbors at kitchen tables and asked the kind of questions people answer when they have been waiting to be asked. “Have you heard shouting?” “Yes.” “Have you seen anything?” “Once he threw a chair; it hit the window, and we thought the glass had cracked.” My sister’s friend told me my mother had slapped her hand for reaching for a cookie “without permission” when we were teenagers; the memory came out of her like something she’d tried to convince herself didn’t matter. I collected dates, times, names. Small stones to build a path.

Step three was leverage. My parents weren’t rich, but they prized an image: the doing grandparents, the long marriage, the church committee that relied on them to bring casseroles and smiles. Masks have seams if you look closely. I went through old bank statements and found withdrawals that had “borrowed” from accounts with my name on them, loans I had chalked up to bad memory, checks I hadn’t written that had cleared anyway. I called a woman my mother worked with and asked a careful question about inventory; petty theft at the register had been chalked up to “mistakes,” but the mistakes had a pattern, and my mother’s initials sat beside the notes. I put it all in a folder. I didn’t need to use it to hurt them. I needed it the way a person keeps an umbrella by the door—because weather changes.

I filed for a restraining order first—for me and for my son. The package my lawyer made was crisp: photos, medical records, dates from neighbors, a transcribed note of the nurse who had wrapped my ribs. We had recorded voicemails where my father had said the quiet part too loud—how “kids only learn when they’re scared,” how I should “be grateful you even have a roof after what you did with that deadbeat.” The judge read, listened, looked at me, looked at the pictures, looked at my son coloring in the corner with a blue crayon, and signed the order. Five hundred feet. No calls. No “accidental” run-ins at the grocery store or sitting on our street in a car with the engine idling. My father’s jaw tightened when he was served. My mother’s mouth made a shape like she’d swallowed something sour. Paper had drawn a circle they couldn’t be inside.

It wasn’t a victory lap. Restraining orders don’t make ghosts of people; they make lines on a map that some people don’t respect. But the first cut had been made.

The second came in bank language. We sued for repayment of funds that had “gone missing” over years. It wasn’t a mountain of money. It was the decimal points that tell a story about entitlement: ten here, sixty there, a thousand for a “repair” that never happened. The point was not the sum. The point was the record. Things you can prove change the way a room behaves. My lawyer told me we would move slowly. Slowness, in this kind of war, is often the loudest thing you can do.

While the civil case crawled, I worked the social ground I used to tiptoe across. My father’s employer received an anonymous package: public records of the assault case and the restraining order, typed cleanly, no commentary, just the architecture of what had happened. My mother’s church group—the women who ran the nursery and made quilts—found a copy of the order slipped, somehow, into the stack of bulletins by the door one Sunday. They called me, left voicemails that began with “We had no idea” and ended with “Please tell us what we can do.” I didn’t call back. I didn’t need apologies; I needed them to stop saying my mother’s name with reverence and start recognizing she had turned love into a knife. They did. Church ladies have their own kind of justice. It hums. It does not forget.

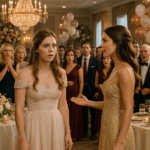

All of this was scaffolding for the moment that would matter most: a mediation room six months later with fluorescent lights that made everyone look tired and a mediator who had heard too many versions of the same story. My parents sat across from me like paper cutouts of themselves, paler than I had ever seen them. My father’s hands shook when he tried to flatten the creases of his shirt cuffs. My mother’s lipstick was uneven—she had rushed, or she had cried, or her hands had shaken, too.

The mediator slid the settlement agreement across the table. It wasn’t only money. It was language. It was an admission of wrongdoing that would sit in their records like a house number no one could change.

“This… this will ruin us,” my father said, and the sentence landed with a thud—the first honest use of “us” from his mouth in years.

“Good,” I said softly. I wasn’t gloating. I was naming a mechanic: cause, effect. He lifted the pen with a hand that trembled slightly, and he signed. My mother signed, too, her face pinched as if the paper smelled bad.

I didn’t stand. Not yet. I took my phone from my bag, chose a file, and pressed play. My father’s voice spilled into the sterile room: “Let her hit the boy.” My mother’s followed: “This is what you get for breeding trash.” Their own sentences filled the air and made the ceiling feel lower.

“You wanted him to see me broken,” I said, nodding toward the door where my son had waited with our neighbor and a book. “Now he gets to see me win.”

I gathered my papers and walked out, not because the moment demanded anything dramatic, but because leaving was the most dramatic way to honor the girl I used to be—the one who had stood between a raised hand and a child and taken the blow without looking away.

In the years that followed, payments arrived like clockwork, monthly, antiseptic, a machine humming far away. Each one was not an apology; it was a receipt. A record that reminds you a crowbar can become an invoice, and an insult can become an exhibit.

My son and I drove past their old house not long after they sold it. The windows were open for the new family, curtains pulled back, a child’s scooter tipped on its side in the yard. My son watched it slide by and said, very quietly, “They can’t hurt us anymore.”

“No,” I said, and for the first time the word felt like a fact and not a hope. “They can’t.”

Justice didn’t arrive with a bang. It came one page at a time until we had a book. It came so steadily that the people who had shouted the loudest found themselves whispering. And in the end, the begging didn’t come from us.

Part 2

I used to think safety would feel like a drumline. It felt more like a kitchen at 6 a.m.: the click of the coffee maker, the whisper of cereal into a bowl, a child’s footfall, my own lungs doing their work without a permission slip. Freedom was ordinary in the best way—nothing rushed, nothing explained.

The months after mediation weren’t a parade. They were a new kind of work. My shoulder healed into a stiffness I learned to negotiate with stretches and forgiveness. My ribs stopped reminding me to sit up slowly. My son learned to sleep without his hand curled into my shirt, a little at a time, like a person teaching a bird to trust a branch.

We went to therapy—both of us. I found a trauma therapist for myself whose office had low light that didn’t make me feel like an interrogation was on the agenda. She listened with the kind of attention that feels like a hand under your spine when you’re learning to float. “What did you learn to believe about yourself in that house?” she asked. I learned to answer without blinking, and then I learned to answer with softness. “That I was the problem,” I said once, and the sentence sounded like a joke no one laughed at. “That I was only loveable when I was quiet.”

My son started play therapy. He built towers and knocked them down and asked, unprompted, if knocking them down made them “bad.” The therapist told him, “It makes you a person.” I watched him run a toy truck along a track and hid my tears in a tissue I pretended was for him. Healing doesn’t always look like breakthroughs. It often looks like a seven-year-old choosing the red crayon again because he likes how it looks on the paper.

I changed our house without warning, the way you pull a splinter and don’t show your child the needle. The lock became a keypad that didn’t fear a stolen key. The back door was reinforced with a plate that satisfied my need to touch metal when my worry ran ahead of me. I got into the habit of putting my phone on the charger by the front door every night, screen lit, voicemail box empty. The absence of messages from numbers I didn’t want to recognize is its own kind of lullaby.

Because the restraining order had been violated almost immediately by a friend-of-a-friend “accidentally” delivering a message to my workplace, my lawyer filed for a renewal. The judge granted it for five more years, and added a paragraph that seemed to change the temperature of the room: violations would be prosecuted. The word prosecuted carries a nice weight when you’ve been told your whole life to lighten up.

There were days I didn’t think about them at all. And then a smell—machine oil, winter air—would punch me into a memory of my father under a sink, the crowbar’s dull sheen translating itself into that tool in my mind. I learned to pause, name it, and then tell the old image to take a number. Other days it was my mother’s perfume, cheap florals that insisted too hard, and the sentence would float up uninvited: breeding trash. Dr. Keating, my therapist, taught me to rewrite it out loud: “This is what you get for choosing yourself.” It felt corny. And it worked.

The money they owed trickled its way to us the way old faucets do, sputtering, sometimes stopping, then starting again after a letter was sent with the word contempt in it. I didn’t spend those checks. I put them in an account I named “Future Stability,” and I let the interest—small as it was—mark time. It wasn’t compensation. It was documentation of consequence.

I kept the folder with copies of everything updated: police reports, hospital records, restraining order renewals, settlement agreements. On top I placed two things: a photo of my son at the park, hair lifted by wind, and the transcript of the mediation recording where they signed their names under the sentence that named what they did. Evidence and joy. I kept them together on purpose.

I started volunteering at a legal clinic once a week. I had learned the language out of necessity: affidavit, petition, motion to continue, ex parte, hearing. I learned to translate it into sentences that make sense to a person whose hands are shaking. “This paper makes a circle on a map the other person can’t walk into. If they do, you call a number. If the number doesn’t answer, you call another number. We will give you both.” I didn’t tell my whole story; I told enough for someone to know I wasn’t reading from a brochure.

The clinic taught free classes at the library: “Documenting Without Dying Inside,” “Paper Trails For People Who Hate Paper,” “Safety Planning 101.” I helped design the slides. On one of them we wrote, in big letters: You are not overreacting. On another, we added: Rest is part of readiness. Seeing those sentences on a screen made my chest loosen. People took photos of the slides with their phones and I watched them exhale. That was the room I needed at twenty. I built it because no one built it for me.

My son’s school counselor suggested we co-write a “body plan” together—simple terms for complex rights. We turned it into a poster for his room. My body is mine. I can say stop. I can tell Mom anything. Adults at school help me. He decorated it with stick figures that all had smiles, an optimistic museum of what we were aiming for. One evening he came home from a classmate’s party and said, offhand, “Jaxon’s dad yelled a lot.” He waited for my face to give him the rule. “What do you think?” I asked. “I think I don’t want to go back alone,” he said. “So we won’t,” I said, and felt something in him settle.

I got a job offer at a nonprofit that provided emergency housing. The interview included a question I had learned to gauge people by: “Why this work?” I answered with the honesty I had earned. “Because I know how quiet people have to be to survive. And because I know what kind of noise saves them.” They hired me. The work was hard in the way that makes you sleep at night because exhaustion is different when it comes with meaning.

On a summer afternoon, I got an email from a journalist working on a piece about community violence and the ways it hides in respectable houses. She had found public records of our case and asked if I’d speak “on background.” I said no, then wrote a long reply about why I said no that turned into the first essay I’d written for someone besides me. I took out the specifics, left in the architecture, and sent it to a magazine that paid a small fee. When they accepted it, I went to the park with my son and bought us ice cream with the deposit. He let his melt faster than recommended. We laughed like people whose bodies knew how.

A year after the mediation, a letter from my mother arrived in a handwriting I would have known by its pressure anywhere. I opened it without meaning to; muscle memory is quick. She wrote that she was “sorry if” she had “ever hurt” me. The if made my vision white for a second. She wrote that she had started attending a support group and church had “welcomed her back,” and she wanted to “start fresh.” I put the letter on the counter and made dinner. After my son was asleep, I sat with the letter again and wrote No across the top, not in reply to her, but as a sentence my house could see. Then I shredded it. Closure isn’t a door you slam. Sometimes it’s a recycling bin you shut quietly with your foot.

Not long after, a friend texted that she had seen my father leaving a courthouse. The part of me that used to keep a weather eye on the horizon for storms bristled. Google told me he had been picked up for violating the restraining order—appearing at a school event we had not attended but that the order forbade, “coincidentally,” of course. He pleaded to a misdemeanor and got probation. The judge added mandatory classes about boundaries. I didn’t circle the date on a calendar; I wrote a single line in my notebook: Even old circles can hold.

We moved to a different apartment with more light and a second bedroom. I painted one wall in my son’s room a blue that looked like skies from the cartoons he loved. He picked out a rug shaped like a racetrack and ran toy cars along its edges, narrating their journeys. On the first night in the new place, he said, “It’s quiet,” like he was tasting a new fruit. I said, “Listen,” and we listened together—to the refrigerator hum, to a neighbor’s soft guitar, to nothing that made our shoulders jump.

He asked about his grandfather and grandmother sometimes. I told him the truth the way you pour water slowly into a plant you’re learning not to drown. “They made choices that weren’t safe. They hurt us. The court told them they can’t be near us. Maybe one day we’ll write them a letter. Maybe not. Either way, we’re okay.” He accepted the sentences like he accepted that some cartoons were off-limits because they gave him bad dreams. Kids respect boundaries when they see the adults who make them respect themselves.

Two Springs later, the old house went up for sale. The listing photos made me dizzy—the same window over the kitchen sink, the cabinet my father had fixed framed just so. My phone buzzed with a message from a former neighbor: It sold. I drove past without slowing, then circled the block and let myself look. A tricycle in the yard. A wind chime my mother would have declared “tacky.” My son pointed out a squirrel with its cheeks full and we laughed. We didn’t mention the crowbar. That’s the thing about memories: you don’t owe them every drive-by.

I got a call from the legal clinic one Tuesday: a woman whose partner had been arrested was in the lobby with a toddler and a plastic bag of clothes. Could I come early? I went. She sat with her palms flat on her knees, as if her hands needed to be reminded what they were for. I knelt beside her and said, “I’m so sorry.” She nodded but didn’t look at me. “Everyone says sorry,” she whispered. “Can you help?” We did. We called the shelter and a locksmith and her sister. We found her a phone charger. We filled out forms that make circles on maps. When she left, she squeezed my hand and said, “I didn’t know who to call.” I told her what I wish someone had told me: “You call us. Then you call yourself brave.”

On the second anniversary of the mediation, I spoke at a neighborhood forum about “breaking cycles.” It was held in the gym of a middle school, the same kind of cinderblock room where my father used to watch my sister play basketball and shout at referees. I stood behind a folding table with a paper cup of water and told a shorter version of the long thing: that a crowbar doesn’t get to decide the rest of your life; that restraining orders are not magic but they are spells; that justice is usually boring and that boredom might be a kind of miracle when your body has lived on adrenaline. When I finished, an older man with kind eyes came up and said, “I didn’t know. My house was like yours when I was a boy. I never knew what to do with that.” I shook his hand and said, “You’re doing it now.”

We took a trip, just the two of us, to a beach town in late September when the sand belongs to locals and the gulls are full of summer’s mistakes. My son learned to body surf in waves the size of our couch. I learned to sleep through a night without my phone under my pillow. On the last day, he drew a picture in the sand of a stick figure holding the hand of a smaller stick figure. Above them, he wrote M O M. He drew a heart around it in a lopsided shape that felt like our lives: imperfect, defiant, complete.

The last letter I got from my parents’ lawyer arrived with a check. The memo line read: final payment. I stared at those two words until they lost their shape. I deposited it. Then I walked to the park and sat on a bench. I closed my eyes and thanked the quiet for holding us. I didn’t feel triumphant. I felt… finished with something I hadn’t realized I was still carrying.

We celebrated with pizza in the living room on a Wednesday for no reason other than that reasons don’t get to own celebration. My son asked if the check meant we could buy a dog. I said yes, because progress deserves to wear joy like a collar. We went to the shelter that weekend and came home with a mutt who looked like he had licked a painter and wasn’t sorry. My son named him Rocket. Rocket learned our routines and taught us a few of his own—namely that love can be as simple as a warm weight against your feet while you read.

One winter afternoon, my phone buzzed with a number I didn’t recognize. I let it go to voicemail, then listened. My father’s voice came through, older at the edges. “I know I can’t call. I know this violates. I just—” He stopped, started. “I’m… sorry.” He hung up. I saved the audio in a folder called Not For Me. Then I forwarded it to my lawyer with a single line: Please handle. Apology without accountability is a bird that insists it can fly after it’s been salted. I didn’t need to be the wind beneath that.

The next time my son and I drove past the old house, he rolled down his window. We could hear wind chimes and kids yelling about tag. “They can’t hurt us,” he said again, like a chant he needed to hear in his own voice. “They can’t,” I agreed, and then added the sentence that felt like planting a flag: “And they can’t tell us who we are.”

Because here is what we are: two people who learned to hold a line for each other. A dog who believes every room is a parade route. A kitchen that knows the difference between footsteps that make you flinch and footsteps that make you smile. A folder that holds proof we survived and proof we built a life. A mother who stepped between a raised hand and a boy and found out she was made of something steel can’t bruise. A child who grew up knowing he was never the reason for harm and always the reason for healing.

I still keep the crowbar in my mind—its shape, its coldness—not as a talisman, but as a measurement. On the other side of it sits a box of school art, a stack of rent receipts, a leash, a new lock, a poster that reads My Body Is Mine with a crayon sun in the corner. On the other side of it sits a woman at a table teaching someone else how to fill out forms without shaking. On the other side of it sits a boy who will learn to say No in a voice that sounds like an inheritance I wanted him to have.

The world will always have people who think a weapon proves a point, that fear is a tool, that control is love. I cannot fix the world. I can fix our house. I can make circles on maps and slide papers across desks and tell the truth into rooms that forgot what it sounds like. I can raise a child who laughs freely and a dog who sleeps deeply and a life that keeps its promises.

And I can keep my promise to myself: that the night they thought they destroyed me would be the night I began to dismantle them. Piece by piece. Paper by paper. Until the only begging left in the story came from them.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS. CH2

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS Part 1…

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call. CH2

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call….

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant. CH2

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

End of content

No more pages to load