Part One

Two weeks, Jerry said, engine noise hissing under his words, just to land on my feet.

My name is Lisa Horton. I’m thirty‑two. I work the front desk at a community clinic in Ketaring, Ohio, and three years ago I bought a small two‑bedroom ranch with a sagging carport and a sycamore that leans like it’s listening. My older brother, Jerry, is thirty‑five and freshly divorced. Our mom, Audrey, is sixty‑one; our dad, Randall, sixty‑three. They raised us on the idea that family helps first and figures out the details later.

So I stared at my living room—brown couch, folded throw blanket, the coffee table I inherited from Grandma—and said yes.

He pulled up that Tuesday night, February 20th, headlights washing across my front window like someone opening a curtain. He came in with a duffel slung over one shoulder and a plastic grocery bag looped over his wrist. The bag clinked with two beers and—when he set it down—breath mints.

“Thanks,” he said. A half‑smile that had gotten us out of trouble when we were teenagers and got him into leases he shouldn’t have signed at twenty‑eight. “You’re a lifesaver.”

“I’ve got the couch made up,” I said, tapping the arm where the clean sheet was already tucked under a cushion. He didn’t take off his coat.

We ate pizza off paper plates and pretended to care about a basketball game neither of us was following. He mentioned “lawyers” once, then avoided eye contact like he’d set down a glass too close to the edge of a table and felt it wobble. I didn’t press. I handed him an extra pillow. By midnight he was asleep with the TV on low, a blue rectangle breathing under his cheek.

I turned off the lamp and tried not to think about whether “two weeks” could stretch the way an old sweater does.

The first nights were quiet. He woke early and left a coffee ring on the counter like a little moon. He stacked his duffel under the coffee table like it lived there. He kept his charger plugged into the outlet by the couch. He showered quick. He was polite in the way people are when they don’t want to owe you anything: wiped the stove after bacon, held the door with a boot when I came in juggling my lunch and a tote.

I told myself I could absorb two weeks.

On Thursday I texted Mom: Jerry’s here for a bit. She replied, Good. Be kind. He’s hurting. Dad sent a 👍. I could hear them on speakerphone telling him he’d bounce back, saying my house was a soft place to land. I wanted it to be.

By day five, he’d found the spare key bowl by the door and dropped his fob in with a little clatter that said I belong. By day seven, he borrowed my car vacuum and left the cord coiled on the porch like a snake shedding skin. On day eight, he asked if he could use my laundry “because the laundromat eats quarters.” I said yes because it wasn’t a big deal. Because it was just two weeks.

March 1st, day ten, I came home to the beep of my thermostat. He was standing under the vent, hands out like he was testing rain.

“What’s up?” I asked, hanging my keys on the hook.

“Your place runs cold,” he said, tapping the thermostat again like it might reveal a secret setting. “I bumped it to seventy. You’ll thank me.”

“I keep it at sixty‑six when I’m at work,” I said. “It’s fine, I promise.”

“Sixty‑six?” He laughed like I’d confessed to living on icicles. “You’re a penguin.”

I shrugged, went to change, and tapped it back after he got in the shower. That night the furnace kicked on and off like it had something to prove. I put on socks.

The days blurred in that slow, ordinary way. I went to the clinic, checked in patients who forgot their insurance cards, slid clipboards across the counter, answered calls. I came home to Jerry on my couch watching clips on his phone with the volume up: laughing babies, men falling off ladders, a guy who makes towers out of playing cards. He said he was sending résumés. I didn’t ask to see them. He told me he’d Venmo me for groceries. I nodded—and realized I’d never discussed groceries.

He had that charming helpfulness that performs well in front of witnesses: opened the car door when he caught me in the driveway, carried the brown paper bag into the kitchen with exaggerated care and set it on the counter like he was unloading a baby. He was allergic to specifics—numbers, dates, the exact place I liked the thermostat. I am the person who lives on specifics. Appointment times, co‑pay amounts, the green highlighter I use for “rescheduled” in the appointment book.

I reminded myself: two weeks.

On day twelve, he invited me to watch a movie and fell asleep twenty minutes in, snoring gently while the credits rolled. I washed the pizza cutter and put the leftovers in the fridge. I placed his charger neatly on the coffee table like tidiness might make the house feel like mine.

On Sunday, March 3rd, I put Mom and Dad on speaker while I folded towels.

“How’s our boy?” Mom asked.

“He’s fine,” I said, quietly.

“Good,” she said. “Be patient. These things take time.”

Dad said, “Good. You’re helping,” and cleared his throat the way he does when a conversation is over.

I circled March 5th on my paper calendar—two weeks. In ink, it looked small.

Day fourteen, he came out of the bathroom with a towel over his head, steam following him down the hall. He opened the cabinet above the washer, looking around like my house was a retail aisle.

“Hey, Liss,” he called, standing in the doorway in clean socks. “Where do you keep the spare pillows? I’m rinsing a mug.”

“Why?”

“For when a buddy crashes,” he said, grin casual, like he was asking for salt.

The buddy arrived the same night: a knock at 9:30, a gust of cold, a guy in a baseball cap who said “Yo” like my living room was a bar he’d been to before. Jerry waved him in with the confident ease of someone who doesn’t wonder whose name is on the deed.

“I told him he could crash,” Jerry said to me. “Just for tonight.”

“Okay,” I said—because the two weeks ended today and picking a fight over a pillow felt small compared to the bigger thing I was avoiding.

They turned the couch into a fort. They turned the tv up and YouTube brighter. At 11:58, I brushed my teeth, put in earplugs, and told myself I could sleep through anything.

At 12:40 a.m., the washing machine started thumping. Not the gentle kind. The off‑balance, heavy‑denim thud‑thud‑thud that made the floor vibrate. I stared at the ceiling in the blue dark and breathed like I do for blood pressure readings at the clinic. It went through rinse, spin, another load. The dryer hummed. The vent rattled in the hall.

At 6:10 I made coffee and opened the pantry. The cereal box was back in place but light—just chaff and dust. The coffee bag was folded crooked and empty. There was an energy drink can on the counter leaving a wet ring.

Jerry’s buddy was face down on the couch. Jerry was sprawled on the rug, my throw blanket half on, half off. I typed a text from the kitchen: Need quiet on work nights. Also, if you finish something, please replace it. He didn’t respond.

At the clinic, Tessa leaned on my desk with her water bottle and arched an eyebrow over her glasses. “You good?”

“Just didn’t sleep,” I said, sliding an insurance card back to a teenager with a sprained wrist.

“Put a lock on your coffee,” she said, half‑joking, and my laugh came out flatter than I meant it to.

At lunch, I opened the utility portal and looked at the usage graph. The bar for March already spiked taller than February’s, even though it was barely begun. I took a photo with my phone—the number bright and rude. I opened a new note and titled it House Costs—Jerry. I typed: 3/2–3/5 Midnight Laundry, Coffee + Cereal gone. I added Thermostat bumped to 70 on 3/1. I attached the screenshot of the graph. Petty. Necessary.

When I got home, the buddy was gone. The couch smelled like cologne. There was a new cereal box on the counter—wrong brand, sugar crusted around the bag opening.

“I replaced it,” Jerry said, proud.

“Thanks,” I said, and poured a bowl. It tasted like frosting and regret. I ate two bites and slid it into the sink.

That night I said, “Hey, can we keep it down after ten? I’m up at six.”

He looked up from his phone, thumb hovering. “Li‑i‑i‑sa, you’re uptight. It was one night.”

“It’s a work night,” I said. “And the laundry at one a.m.—”

“It needed to be done,” he said, like gravity. “Laundromat’s closed by then. I’ll be quiet.”

He turned back to his screen.

On Thursday, Mom called while I stirred pasta. “How’s our boy?”

“He had a friend over. They did laundry at one a.m.”

A pause where she selected a gentle scolding. “Be kind. He’s hurting. Divorce scrambles people.”

“I’m kind,” I said, “and I’m tired.”

“Just breathe,” she said. “He won’t be there forever.”

I put her on speaker and, with my free hand, took a photo when the power bill hit my inbox. I added it to the note. I poured out the pasta. Steam fogged my glasses.

Friday, I yawned my way through intake. A man argued about a co‑pay and I smiled until my cheeks ached. Tessa slid me half her granola bar.

“Weekend plan?” she asked.

“Laundry,” I said, and we both laughed too hard.

Saturday morning, I mopped the kitchen and found lint like someone had emptied a pocket on the floor. I wiped a smear off the fridge. I stacked my receipts by the microwave and took a photo of those too. Not a spreadsheet, but not nothing.

Jerry facetimed loudly that night. At midnight he was still talking. At 12:30 the toilet ran. At 1:10 the washer thumped. I added 3/9—Laundry 1:10 a.m. to my note without turning on the light.

Sunday I told him again. “Please—quiet on weeknights.”

He lifted a hand without looking. “Chill, Lisa. Seriously.”

On Monday my phone pinged at 5:42 a.m.—low balance alert. The furnace roared; the electric autopay posted; I moved $50 from savings to cover groceries and sat on the bed with socks in my hands, awake in the wired way that has nothing to do with rest.

Tessa stopped by my desk with a paper cup of cafeteria coffee. “You look like you slept in a dryer.”

“Close,” I said. “I’m talking to him tonight.”

“Good,” she said. “Say a number. Don’t apologize for the number.”

By Tuesday night, I’d rehearsed it enough times my mouth knew the words.

“Can we sit at the kitchen table?” I asked.

He draped himself into the chair, legs open like he’d been asked to pose.

“You asked for two weeks,” I said. “It’s been three. I need $200 toward the mortgage and half the utilities while you’re here. And quiet after ten.”

He barked a surprised laugh. “Charging your brother rent to sleep on a couch? That’s wild.”

“Not rent.” I kept my voice steady. “Contribution. The bills went up. I can show you the usage.”

“You got real tight since you bought this place.” His smile didn’t reach me.

I let the silence sit until it was a third person at the table.

He typed into the family thread where Mom and Dad live: Imagine your kid charging you rent to sleep on her couch. Bitter landlady energy. Wow.

Mom: Lisa, honey, he’s in a hard place. Keep perspective.

Me: I am keeping perspective. I’m also paying for everything. This is what I can do.

Dad reacted with 👍. Which is not a side. Or maybe it is.

I sent Jerry a text with photos attached: the usage graph, the bills, the receipts. I’m asking $200 and half utilities. Going forward, same on the 1st. Quiet after ten on weeknights. His phone showed Read under each image. I screenshotted that, too. Then I stacked the electric and gas bills on my coffee table and took a photo of those—because sometimes even I don’t believe myself until the evidence has its shoes on.

He stood, pushed the chair with his knee, and said the sentence that pretends to be a promise. “I’ll figure it out.”

“By Friday works,” I said.

On Friday there was no Venmo. On Saturday there was laundry at 1:00 a.m. On Sunday, roast at Mom’s and the quiet nod Dad does when he doesn’t want to choose. I kept my voice clean and my pen full.

By April, my binder had dividers. By May, tabs. By June, a cover sheet: Utilities—Jerry. I handwrote monthly totals so I wouldn’t have to add them in my head. 3—148; 4—201; 5—236; 6—189. In July I stopped writing apologies in the margins and wrote quiet after ten in block letters so I would remember my own rule.

“Stop keeping it in your head,” Tessa said one Tuesday, pulling up the county clerk’s website on the break‑room computer. “If you’re serious, start the paper trail. There’s a 30‑day termination of tenancy template here. It’s not eviction. It’s notice.”

On my lunch break I typed my name and address into the blanks and emailed the PDF to my home printer. I made a one‑page itemization with columns in Word: Date / What / Amount / Proof. I printed the portal screenshots: electric usage spikes; gas therms jumping when the thermostat read HOLD; water gallons by day—resulting in a little silent scream that looked like a grid of blue bars.

I taped a pen inside a manila folder and felt like a parody of myself. Then I put the folder on my coffee table and sat there until my pulse slowed.

Late August, Mom texted hearts and Roast at 6. I went. Jerry smirked and said, “She’s still got me on a meter,” like a man telling a joke to a friendly bartender.

I opened the folder and set the pages beside the gravy boat like a second centerpiece.

“I’m going to read this,” I said—not loud; not apologetic.

Jerry’s grin sharpened with amusement. Mom’s fork touched china; Dad stared at his glass.

“Utilities only,” I said. “Six months. March, $148. April, $201. May, $236. June, $189. July, $208. August, $198.” I kept my tone even. “Total: $1,180—utilities only.”

I slid the notice toward him, the date line filled in: 30 days from today. “This ends on this date,” I said. “If you haven’t moved or paid, I’m filing in small claims.”

“You’re not going to do that,” he said, smirk wide as a dare. “You’re making a scene to impress Tessa and the audience.” He gestured toward our parents.

“It’s dinner,” Mom hissed. “Mashed potatoes are getting cold. Pass your sister the rolls.”

“I’m good,” I said.

I put the papers back in the folder, left the notice in front of him, and concentrated on breathing instead of shaking. After water and help with foil, I hugged my mother in the doorway. She whispered, “You didn’t have to—”

“I did,” I said. “So everyone heard the same thing.”

In the car, my hands shook anyway. In my bedroom, I pulled my paper calendar down, took a red pen, and went over the pencil circle I’d made around day thirty‑one. Then I wrote File in the box like a person writing a grocery list item they were finally going to buy.

Day thirty‑one was a Tuesday. My shoes went on, my coffee came from the emergency stash I now kept in my bedroom, and I drove to the courthouse with the binder buckled in the passenger seat. The clerk stamped the top page with blue ink that left a neat bruise of authority and handed me a case number.

That evening, a process server with a windbreaker and a clipboard taped the summons to my door and took a photo. Jerry peeled it off, skimmed it, and snorted. “You really did it.”

“I really did,” I said.

He texted that he’d be gone by morning. A pickup arrived. There went the duffel that had lived under my table, the laundry basket full of rolled T‑shirts, a plastic bin of cords, boots, hangers, his pillow. He took his charger, set the key on the counter like it was hot, and muttered, “Chill.”

When the door closed, the house exhaled. I turned the thermostat back to sixty‑six and hit Cancel on Hold. The HVAC sounded less like a freight train and more like a promise.

Mom called. “You didn’t have to go nuclear.”

“I didn’t,” I said. “Small claims. Thirty days. He can talk to the judge.”

“You know he’s hurting.”

“I know,” I said. “And I’m paying the bills. I can know both.”

We hung up without a blessing or a curse. I picked up the copy the process server had slipped through the mail slot and set it on the coffee table. The case number looked like a spine. I put my red pen next to it.

Part Two

Four weeks softened and hardened like dough rising and then baking. I fed the binder new pages when they arrived; I practiced sentences in my head and then in the mirror until they felt like mine. I bought two deadbolts and a keypad lock and a window AC unit with Sleep Mode written on the box in tiny letters. I installed them on a Saturday with the radio low and the doors propped open. When the keypad beeped, I punched a code I’d remember and deleted the habit where I left the spare key in the bowl like a superstition.

The hearing was on a Tuesday. I sat outside a small courtroom on a wooden bench with my binder in my lap, case number on a pink postcard in my hand. Tessa texted you got this and a string of biceps. Her “bring paper not vibes” line had become my weird prayer.

A bailiff opened the door and called the case. Jerry was already inside, wearing a clean T‑shirt and a jacket, hair combed like it was a job interview. He didn’t look at me. The judge—Tyrell Lewis, the nameplate said—looked like a man who read instructions before assembling furniture.

“Small claims,” he said, settling in. “Keep statements short. I need receipts, not speeches.”

I stood at the plaintiff’s table. The bailiff swore us in. I took a breath that hit bottom for the first time in months.

“Ms. Horton, your claim?” Judge Lewis asked.

“Utilities,” I said. “My brother moved in February twentieth, said two weeks, stayed six months. I asked for $200 toward housing and half utilities. He didn’t pay. My usage and bills increased while he was there. I’m asking for $1,180—utilities only—for March through August. Plus the filing fee.”

“Proof,” the judge said.

I slid the binder across, open to the timeline: Move‑in 2/20; Buddy overnight 3/5; Laundry 12:40 a.m. 3/6; Text 3/12 Request $200 + 1/2 Utilities (Read); 30‑Day Notice 8/27 (Delivered). Then bills, with dates and amounts circled; screenshots from the utility portal showing bars jumping like the heartbeat of a house trying to keep up with someone else’s habits; the water portal showing gallons spiking on laundry nights; photos of the thermostat set to HOLD 69 and HOLD 64 with timestamps; the text thread where I asked for contribution and quiet and watched the little Read stamp appear under my words.

Judge Lewis turned pages slowly, reading the monthly totals I’d written in neat pen—3—148; 4—201; 5—236; 6—189; 7—208; 8—198—murmuring them like sums at a grocery register. He looked up.

“Mr. Horton,” he said, even. “Any proof of payment? Venmo? Checks? Cash receipts for groceries?”

Jerry shifted and smiled, the kind people use on flight attendants and waitresses. “I replaced things,” he said. “I helped around the house. She’s making this bigger than it is. We’re family.”

“Receipts,” Judge Lewis repeated, not mean. Just exact.

“No,” Jerry said.

The judge tapped the binder with his pen. “You asked in writing for contribution,” he said to me. “He read it. Your usage increased.” He nodded once. “On the claim for utilities, March through August, I award the plaintiff $1,180. Court costs $75, total judgment $1,255. Payment arrangements are between the parties. If you don’t pay, Ms. Horton may pursue collection.”

The gavel wasn’t dramatic. It was a pen scratching a date. It felt more satisfying than any gavel would have.

In the hallway, Jerry stared at the floor tiles like they might spell out a different verdict. “I’ll figure it out,” he muttered—the same non‑promise he’d tried to feed me for months.

I nodded because I didn’t owe him anything else. I texted Tessa Awarded. She replied with fireworks that made me grin like a fool in the fluorescent light.

That afternoon I went home, put the stamped judgment in the front pocket of the binder, and slid the binder onto the shelf with the appliance manuals and the little fireproof envelope with my deed. Boring belongs where I can reach it.

For a week nothing happened. Then: Venmo—$100 (memo: utilities). The next week: $100. The next: $200. He didn’t say anything. Neither did I. In between payments, a text arrived that looked like he’d argued with his pride and lost: I’m sorry. I was wrong. I put you in a bad spot and made it worse. I’m working on it.

I appreciate the apology, I typed back. No emojis. No debrief.

On Sunday, Mom didn’t lecture me. She hugged me at the door, packed leftovers into a foil‑lined bag like she always does: roast, green beans, a roll, a brownie in wax paper because Randall “doesn’t need it.” Dad said, “Clinic busy?” and I said, “It’ll pick up,” and he nodded like we both understand how seasons work.

The second Sunday, Jerry came. He said hello like he was trying out a new vowel. He talked to Dad about football. He didn’t make jokes about meters or landladies. Mom squeezed my arm when I left and said, “Drive safe,” like she meant only that.

At home, I slept with the new window unit on Low just because I could. The cool air was a ribbon that didn’t intrude or announce itself, it just kept a promise. I replaced the batteries in the smoke detector and finally oiled the hinge on my bedroom door so it wouldn’t announce my movements like an accusation.

On Tuesday, my cousin texted: Random—could my friend crash for a week? She’s in a rough spot. Older me would have answered yes and rearranged my irritation for company. Current me attached a PDF I’d made with Tessa over lunch—Temporary Stay Agreement—three paragraphs and bullet points:

Dates: Start/End

Contribution: Half utilities; $250 refundable deposit

Quiet hours: 10 p.m.–6 a.m.

Thermostat: 67–70

No overnight guests without permission

Signatures

Happy to help if these terms work, I wrote. Deposit required before arrival.

Three dots. Then: Totally get it. Let me show her.

I put my phone down and opened the front window. The neighborhood smelled like cut grass. A kid on a too‑small bike wobbled by and waved the way kids wave at any adult who waves back. I waved. The keypad on the front door blinked once, content.

At the clinic, a woman with a tight ponytail argued about a co‑pay and I said, “I understand,” and slid a printed financial‑assistance form across the counter and explained it in small bites. Tessa leaned over later and said, “That, but for your house,” and I laughed because she was right.

When the October electric bill arrived and it was lower than September’s by $32, I printed it anyway—because proof makes a different part of my brain relax. I thought about taping it to the fridge like a second‑grader’s spelling test, then put it in the binder instead, behind the judgment, because my own pride needed to learn where to live.

In November, Mom called asking if I’d do Thanksgiving—which, in our family, is shorthand for Can we all come to your house? I said yes and sent a group text three days later with arrival window and what to bring and please no laundry loads today typed kindly and clearly. Randall sent a turkey emoji and 10 a.m. Jerry sent I’ll bring pies and then, five minutes later, store bought is okay, right? It was the first time he had asked a question that implied he did not get to assume.

There are a hundred small endings in any big ending. Here are some of mine:

The day I moved my coffee back to the kitchen and it stayed there overnight, intact.

The first Sunday I left Mom’s with leftovers and did not bring back a new bruise from a joke.

The morning I woke at 6 without a furnace roaring like a freight train and realized my jaw wasn’t clenched.

The moment I put the spare key in a lockable drawer and didn’t feel mean, just safe.

The minute I stopped thinking about my house as a test I was failing and started thinking about it as a thing I take care of and that takes care of me back.

I do not keep score in my head anymore. I keep records where they belong. I write rules down because paper makes my mouth brave. I say my numbers out loud. I stop writing apologies in the margins.

Sometimes at the clinic a patient will roll their eyes at a co‑pay and someone in my head will laugh and I will think of Jerry. And then I will slide the paper across the counter and say, gently, “Here are your options,” and the part of me that survived this will thrum quietly like the window unit on Sleep Mode.

People ask—Tessa, Mom in a sideways way, a neighbor who heard things the way neighborhoods do—if the court felt like victory. I say no. It felt like math. It felt like putting a period where a sentence kept running on because I was a woman and loved and had been told to write in pencil.

If Jerry sends the last of the judgment, I will cash it and move on. If he doesn’t, the paper is there, stamped and calm, waiting in the binder on the shelf.

On a Sunday evening in late December, snow sifts down like dust caught in a beam of light. I hang a new calendar on the wall with a magnet shaped like a tomato. In the square for the first Sunday of the new year I write Roast 6? with a question mark because I can ask for what I want now and accept the answer without rearranging my whole body around it.

The house hums. The thermostat reads 66 because I chose it and not because someone else claimed it. I set out two mugs. Tessa is coming over with cinnamon rolls that smell like what people mean when they say home.

I open the front door without the old habit of looking to see if someone has taped something there that will change my life. The keypad blinks. The air that slides in is cold and sweet.

Two weeks, Jerry had said. He took six months. He ate six months of bills. I ate the anger, slowly, and then I built something with the energy: tabs and lists, a clean sentence in a judge’s mouth, a red circle on a calendar, a lock that beeps. It turns out you can do a lot with specificity and a friend who says bring paper not vibes.

And when I turn off the lights and the window unit ticks once and goes still, it feels less like an ending than the thing endings make room for.

News

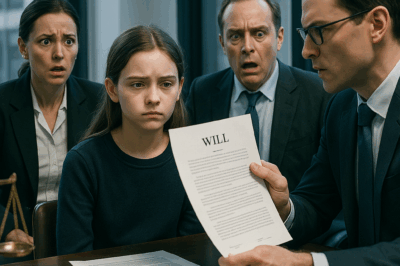

My aunt’s inheritance gave me a house and two million dollars. Out of nowhere, my parents—who hadn’t been in my life for 15 years—appeared at the will reading, saying, “We’re your guardians.” When my lawyer stepped in, their faces drained of color. Ch2

Yesterday, at 28 years old, I became a millionaire. My Aunt Vivien, the woman who raised me, left me everything:…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

My ex-husbamd bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… CH2

My ex-husband bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… Part One My…

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… CH2

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… Part One…

After my dad’s funeral, my SIL suddenly said the inheritance goes to her husband. I was stunned… CH2

After my dad’s funeral, my SIL suddenly said the inheritance goes to her husband. I was stunned… Part One I’m…

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so i left in silence. Then they started panicking… CH2

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so I left in silence. Then they started panicking… Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load