My Brother Married My Best Friend And Tried To Take My Inheritance, Until Grandma Stepped In

Part 1

The envelope looked like money.

Thick, cream stock. Edges beveled just enough to say “custom” without saying “obscene.” My name, Monica Harvey, swooped across the front in gold calligraphy that probably had its own Pinterest board.

I didn’t have to open it to know what it was.

“You’ve been glaring at that thing for ten minutes,” Sullivan said from my kitchen, where he was committing to his second mug of coffee like it was a relationship. “Planning to vaporize it with your eyes, or…?”

“I can do hard things,” I said, and slid my thumb under the flap.

The card inside was exactly what I expected and somehow worse.

A photo first: my older brother, Riker, in a navy suit, dimples engaged, his hand on the waist of my best friend—ex-best friend?—Jolie. They were in a field somewhere, golden light behind them, hired photographer in front of them, happiness art-directed to death.

Then the lettering, all loops and flourishes:

You are cordially invited to celebrate the union of Riker James Harvey and Jolie Anne Rhodes.

“It’s official,” Sullivan said. “We’ve moved from betrayal to branding.”

“I think I’m going to be sick.” I dropped onto the couch. The invitation slipped from my fingers and landed face-up on the rug, smiling up at me like a smug cat.

He came over, picked it up, studied it. “At least the font’s nice?”

“I introduced them,” I said. “Jolie and I were supposed to be each other’s maids of honor. We swore it in a Taco Bell parking lot at two in the morning. That has to be legally binding.”

“You don’t have to go,” he reminded me.

“I do.” I stared at the photo until my eyes blurred. “If I stay home, I’m the bitter little sister who couldn’t handle their true love. If I go, I’m the prop in his PR campaign. Those are the options.”

My phone buzzed on the coffee table.

Did you get it? Isn’t it beautiful?

My mother. Of course. No hello, just an assessment.

I typed back: Yes, Mom.

Three dots pulsed for two full seconds.

Now, I know this is complicated, she wrote, which in Mom-speak meant I was about to be told to grow up. But your brother is happy. The least you can do is show up for us.

I made a face. Sullivan peered over my shoulder. “She hit you with the least you can do?”

“Classic.” I forced my fingers to be polite. I’ll be there.

Good, she replied. Also, your father wants a family meeting tomorrow at seven. Estate planning. With the wedding coming, we need to finalize things.

There it was. The other shoe.

“Estate planning?” Sullivan echoed when I read it aloud.

“Translation,” I said. “Dad and Riker have found a new way to make sure the trust looks like it’s about ‘protecting the family legacy’ while actually being about ‘protecting Riker’s ability to do whatever he wants.’”

The Harveys didn’t just have money. We had capital-F Family Money, layered in real estate and hotels and an investment portfolio that needed its own babysitter. My grandfather had built the foundation brick by brick; my grandmother, Rosaline, had kept the whole thing from sinking into the swamp of male ego more times than I could count.

The trust—The Harvey Family Trust, spoken in capital letters—was what everything sat inside. It was also the fault line under every holiday dinner.

My phone lit again. A new message, this one from a contact saved simply as: R.

You okay, kiddo?

Riker never called unless he wanted something or wanted you to think he was the kind of brother who called.

I typed and deleted three different versions of go to hell. Ended up sending: Busy. Talk later.

Sullivan took my empty mug to the sink. “You think this ‘estate planning’ is about the wedding.”

“I think nothing in this family happens in the same week by accident,” I said. “Grandma is eighty-six. Dad has been making noises about ‘transition planning’ ever since Riker started talking about wanting to ‘streamline decision-making.’ And now my brother’s marrying the woman who knows all my secrets.”

“Just some light, everyday tension,” he said.

He’d known me long enough to understand that “Grandma’s estate” meant a number I couldn’t quite wrap my brain around. Enough that, split evenly between Riker and me like Grandpa’s original trust specified, we could both live comfortably forever. Enough that, consolidated under one name, you could probably buy a country.

My phone buzzed with a third text, this one short and to the point:

Come see me before the meeting. Bring decent coffee, not that sludge your father calls coffee.

—Grandma

I felt a little of the tension slide off my shoulders. “She knows,” I said.

“Rosaline always knows,” Sullivan replied. “Take her the fancy beans. And take notes.”

After he left, I dug a shoebox from the back of my closet. Inside, a decade’s worth of friendship: movie ticket stubs, polaroids, notes passed in class, and birthday cards. I found the last one Jolie had given me.

Best friends until we’re old and weird and yelling at the TV together, she’d written in silver gel pen. No secrets.

I laid that card next to the wedding invitation and stared at them, side by side.

There are metals that look solid until they corrode from the inside. I’d seen that in chemistry. I was about to see it in my family.

The next afternoon, I stood on Grandma’s front porch with a bag of expensive coffee and the sense that I was about to be briefed before a mission.

Her house was old money style—brick, ivy, a front door that weighed more than most people. Inside, it smelled like lemon polish and the perfume she’d worn since 1963.

“In the kitchen,” she called before I had the door fully closed. “And don’t let that coffee get cold. Good beans are wasted on the dead.”

She was at the head of the table, a silk scarf tied around her white hair, reading the Wall Street Journal like it had personally offended her.

“Monica.” She didn’t stand, just held out both hands. I leaned down so she could kiss my cheek. Even her affection had posture. “Put that there.” She pointed at the counter. “Your father will be here in an hour. That gives us forty-five minutes before he starts mansplaining my own trust to me.”

I laughed. “You asked me to bring the good stuff. Single-origin, ridiculously priced. Ground to your specifications.”

“Good girl.” Her eyes, still sharp, flicked to the manila folder on the chair beside her. “You remember what your grandfather used to say about lawyers?”

“‘You keep them on retainer and on a leash,’” I quoted.

“Exactly.” She slid the folder toward me. “Your brother attempted to use one to chew through my ankle.”

Inside: two stacks of paper. One yellowed at the edges—Grandpa’s original trust. I recognized the thick serif font, the precise signatures, the embossed seal. The other—the stack on top—was crisp white, with my father’s name printed at the bottom of several pages and a signature that looked… off.

“What am I looking at?” I asked.

“Your brother’s idea of subtlety,” she said. “He brought a lawyer to ‘review’ the trust last week. Suggested a few ‘modernizations.’ He wasn’t supposed to know I had a copy of my own in the safe. He thought I would just sign whatever your father and his attorney put in front of me.”

I scanned the new language. Phrases jumped out:

— controlling interest to be granted to eldest child upon marriage

— voting rights consolidated for efficiency

— emergency decision-making authority vested in eldest child upon incapacity of Settlor

My stomach pulled tight. “So if this had gone through, once Dad stepped back, Riker would have total control. I’d get… what?”

“An allowance, if he felt generous,” she said. “Your grandfather’s intention was always equal. Fifty-fifty. That’s why he wrote it the way he did. Riker thinks his gender and birth order give him veto power.”

I flipped to the last page. My father’s signature looped across the bottom. “Dad agreed to this?”

“Did he?” Grandma asked mildly. “Read it again. From closer.”

I looked. The signature was my father’s, but not the way it had looked the past two months. “He broke his right wrist in February,” I said slowly. “He’s been signing with his left. His right-hand signature is steadier. This—this looks like his right.”

“And yet,” she said, popping a sugar cube into her mouth. “The document is dated three weeks ago. Doctor’s notes: cast still on. He could not have signed with his right hand.”

“Someone forged it,” I said.

“Sloppily,” she agreed, “which is frankly an insult.”

I kept reading, hands shaking now for reasons that had nothing to do with coffee. “What did Dad say?”

“That he never saw it.” She sipped her coffee, watching me over the rim. “That Riker told him he was taking care of everything. That your brother has been bringing him signature pages and sticky flags for months and he stopped reading.”

I closed the folder, feeling like I’d been handed both a match and a can of gasoline.

“Why are you showing this to me?” I asked. “You could call the district attorney yourself. You could call your lawyer.”

“I already called my lawyer,” she said. “Thomas filed a notice with the court yesterday affirming the original trust and freezing any changes until after my death is probated. No one is touching my estate without a judge and my ghost present. But that’s the legal part.”

“And the part where you drag me into it?”

“That,” she said, leaning forward, “is the family part. You and your brother have been sharing a roof and oxygen since we brought you home from the hospital. I can fix paper. I cannot fix character. You need to see what he’s willing to do to you. And you need to decide who you’re going to be when you walk into that meeting tonight.”

Angry, I thought. Hurt. Reluctant heir to a mess I did not create.

Out loud, I said, “What do you want me to do?”

“For now? Keep your mouth shut and your eyes open.” She tapped the folder. “Take notes. Listen. Let them talk long enough to hang themselves with their own words. Then when it’s time—” the corner of her mouth lifted— “I will step in.”

“And the wedding?” I asked. “You’re really going to let them go through with this circus while we all pretend nothing’s wrong?”

“I’m going to let your brother show us exactly who he is when he thinks he’s winning,” she said. “There is nothing more instructive. As for the girl…”

She hesitated. That alone was sobering.

“What about her?” I pressed.

“She came to see me,” Grandma said. “Alone. Asked to talk about the trust.”

My stomach dipped. “Jolie?”

“She was nervous,” Grandma said. “Kept touching that little necklace she wears. Told me she didn’t want to come between you and your brother. Then he appeared in my doorway without knocking and the conversation ended. He walked her out. Without looking back.”

“So she knows,” I said. “Or at least suspects.”

“Which puts her in the same position you were in this morning,” Grandma said. “Holding a heavy envelope and deciding whether to open it.”

Dad’s voice echoed down the hall. “Mom? We’re here!”

Grandma’s expression sharpened. “Showtime,” she murmured. Then, to me: “Breathe, Monica. And remember—just because you were raised not to make a scene doesn’t mean you aren’t allowed to be the main character.”

Part 2

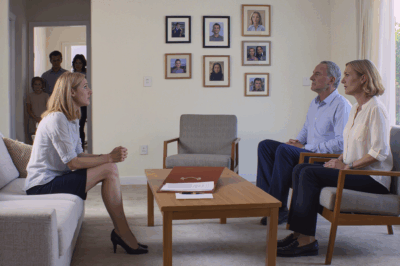

Family meetings at my parents’ house always happened in the same room: the “study,” which was really just a large, wood-paneled theater for my father’s monologues.

By seven p.m., the big desk was cleared, the decanter of scotch was out, and my mother had arranged charcuterie like this was a networking event instead of a potential bloodbath.

Dad stood by the window in a cast that matched his expensive suit, trying to look casual. Mom perched on the edge of the leather loveseat, pearls snug against her throat. Riker was all easy charm in a tailored jacket with no tie, posture relaxed, hair perfect. Jolie stood half a step behind him in a pale green dress, fingers on the little gold bar necklace she’d worn since college.

Grandma made her entrance last, cane tapping a steady rhythm, Thomas the lawyer in her wake like an obedient shadow. She settled into the wingback chair opposite my father with the unhurried confidence of someone who’d been running this show forever.

“Thank you all for coming,” Dad began, because of course he did. “With the wedding coming up and Mom in good health—” he looked at Grandma like she was a car that had just passed inspection— “we thought it was time to update the estate plan. Clean things up.”

“Estate planning,” Mom echoed. “Nothing scary.”

Thomas coughed delicately. “We’re not reinventing the wheel,” he said. “Just… modernizing.”

Riker gave me a look I’d seen on him since we were kids. Relax. I’ve got this. The look that had invariably preceded something being broken.

“It’s simple, really,” he said, sliding a set of papers onto the coffee table. “The world’s different now. We can’t split decisions down the middle forever. Someone has to drive the car.”

“And you,” Grandma said, “have nominated yourself as the driver.”

He smiled like she’d paid him a compliment. “I have the MBA,” he said. “The relationships. The experience.”

I thought about his “experience”—the party in Mykonos that had made Page Six, the near-disaster expansion into a market he’d insisted would be “the next Dubai” and had nearly bankrupted a subsidiary.

“Monica teaches high school English,” Mom added, as if I’d forgotten. “She loves it.”

I do, I thought. That doesn’t mean I’m willing to be cut out.

“Teaching is important,” Riker said quickly. “We’re just saying… you don’t even like this world.” He gestured vaguely at the room, which presumably represented capitalism, hotels, and/or fake plants. “You’ve said it a hundred times.”

“What have I said?” I asked.

“That you didn’t sign up for board meetings and shareholder calls,” he said. “That you’re relieved you’re ‘not the heir.’ I’m not making this up.”

The awful part was, he wasn’t. I had said all of that—and more—on nights when the weight of the family name felt like a coat I couldn’t take off. I’d just never thought he’d weaponize it.

Thomas slid a cleaned-up summary across the table toward me like he was offering a menu instead of a legally binding betrayal.

“We’re proposing a structure where controlling interest in the Harvey Group passes to the eldest child upon marriage,” he said. “It keeps the company consolidated in trusted hands. Keeps out opportunistic spouses. Monica would retain a generous income stream, of course—”

“How generous?” Grandma cut in.

“Five percent of net profits, adjusted annually,” Thomas said. “Indexed to inflation.”

I did the math in my head. It was a lot of money. More than most people would ever see. It was also a leash.

“And decision-making?” I asked.

“Board representation for both of you,” he said. “But final authority with the CEO. For efficiency.”

“For efficiency,” Grandma repeated, as if tasting something sour.

“What about Grandpa’s original language?” I asked. “Equal shares. Equal votes. Remember that?”

“Dad’s not Grandpa,” Riker said. “He wants what’s best for the company now.”

Dad cleared his throat, looking uncomfortable for the first time. “We can’t be stuck in the past forever, Mon,” he said. “The market is ruthless. Your brother has the temperament for it.”

“And I don’t,” I said.

“You’re… sensitive,” Mom offered. “It’s one of your best qualities.”

“You mean I have a conscience,” I said.

Silence rolled through the room like slow thunder.

“Let’s not do this,” Riker said, voice smoothing over the crack. “We’re not cutting you out. You’ll never have to worry about money. You can do what you love. Teach. Travel. Help with the foundation. All without the stress.”

It was an appealing picture. It was also a fantasy built on the assumption that he would always be benevolent. That he would never wake up one day and decide that my five percent was four, then three, then “we had a bad year, sis, you’ll have to tighten your belt.”

Grandma set her coffee cup down with a click. “I have some questions,” she said.

My brother’s jaw tightened. Dad shifted in his seat. Thomas smiled like this was all part of the show.

“Question one,” Grandma said. “Did you truly think I would sign a document I had not read?”

“Of course we expected you to read it, Mom,” Dad said quickly. “We’re just… presenting options.”

“Then I suggest,” she said calmly, “that we all take some time to read.”

I watched Riker’s eyes. Watched the flicker, the flash of irritation. He hadn’t expected resistance. He’d expected a rubber-stamp.

“Fine,” he said. “We can revisit this after the wedding. No need to rush.”

But Grandma was not done.

“Question two,” she said, leisurely flipping through the pages. “Whose signature is this?”

Everyone leaned in. The signature at the bottom of the last page—my father’s name—looked confident. Familiar. Wrong.

“That’s mine,” Dad said, frowning. “Isn’t it?”

“Is it?” she asked. “You tell me, Thomas. You were in the room when he signed.”

Thomas’s composure cracked for the first time. “Mrs. Harvey, I—”

“You what?” she asked. “You watched my son sign with a hand in a cast? You failed to notice the date?”

Dad’s frown deepened. “What date?”

“Three weeks ago,” she said. “When you were still scribbling your name like a drunk toddler with your left hand.”

All eyes went to his right wrist in the still-bulky brace. The color drained from his face.

“I don’t… remember signing this,” he said.

“Convenient,” Grandma murmured. “Thomas, I’d advise you to answer carefully. There are two ways for your career to end. One is retirement. The other is prison.”

The lawyer shot to his feet, papers half-forgotten. “Mrs. Harvey, I can assure you—”

“No,” she said, ice in her tone. “You can’t. Not anymore.”

Mom’s hand flew to her pearls. Jolie’s fingers flew to her necklace. Riker, to his credit, didn’t flinch. He just smiled, slow and almost impressed.

“Congrats, sis,” he said to me. “You got to play detective. You happy now?”

“This isn’t a game,” I said. “You tried to steal from me.”

“I tried to protect the company,” he snapped. “From weak leadership. From outsiders. From mistakes. I tried to do what Dad doesn’t have the guts to do. Someone has to.”

Dad flinched like he’d been slapped.

Grandma stood—slowly, but she stood. “This conversation is over,” she said. “Thomas, you will be hearing from my attorney. Everyone else: go home. Think long and hard about what kind of people you want to be when my lawyers are done.”

Riker scoffed. “You can’t stop this, Grandma. The board wants me. The investors want me.”

“Then by all means,” she said. “Let them see all of you.”

Her gaze cut to Jolie like a scalpel. “Including your choice of wife.”

Jolie paled. “Mrs. Harvey, I—”

“We’ll speak later,” Grandma said. “Without my grandson present.”

The air in the room felt thin.

As Mom shepherded Dad upstairs with murmured reassurances, as Thomas fled, as Grandma retreated with her cane tapping rage, Riker and I were left momentarily alone in the hallway.

“You’re making this harder than it has to be,” he said.

“You forged our father’s signature,” I replied. “There is no easy version of this.”

He stepped closer, dropping the charming big brother act like a coat. “This world eats soft people,” he said. “If I don’t take control, someone else will. An outsider. Jolie’s father. Some hedge fund. At least with me, it stays in the family.”

“You mean it stays under your thumb,” I said.

“Think about it,” he said. “You’re a teacher, Mon. You’re not built for this. Let me be the bad guy.”

“I think you’re doing that just fine on your own,” I said.

He smiled again, cold. “If you walk into that ballroom and try to blow this up at my wedding, Grandma won’t be able to protect you from the blowback. So ask yourself: who do you want as your enemy? Your brother? Or everyone else?”

In my car, in the driveway, my phone buzzed.

Grandma: Tomorrow. Eleven a.m. My office. Just you.

I took a breath and texted back: I’ll bring more coffee.

Part 3

The only room in Harvey Tower that never changed was Grandma’s office.

Below it, floors were renovated according to trends—lobbies went from marble to concrete to recycled glass, restaurants rebranded, bars got new lighting every decade. But the top suite stayed exactly as it had been when Grandpa signed the first loan papers: heavy desk, green banker’s lamp, shelves floor to ceiling with ledgers and old leather books.

The morning after the family meeting, I walked in with two coffees and the ridiculous feeling that I was twelve and about to be both scolded and rewarded.

Grandma sat behind the desk, signing something with a fountain pen I’d once been told cost more than my first car. Sullivan was in one of the leather chairs opposite her, tie loose, jacket off, laptop balanced on his knee.

“You’re late,” she said.

“It’s eleven-oh-two,” I protested.

“Exactly,” she replied. “Sit. Both of you need to hear this.”

Sullivan handed me a folder. Inside: a stack of emails, printed and highlighted. The headers told a story—messages between Riker and various board members, between Riker and an outside law firm, between Riker and… Jolie’s father.

“You’ve been snooping,” I said to Sullivan.

He shrugged. “I prefer the term ‘auditing.’ Grandma asked me to look into any… unusual activity.”

Grandma waved a hand. “Savings. Shares. Back-channel phone calls. Your brother has been rearranging chairs on the deck of this ship for a year. But that signature stunt was his first felony.”

“What is this?” I asked, tapping a printout.

“Leverage,” Sullivan said. “He’s been gathering dirt. On your dad, on some sketchy merger from the nineties, on suppliers. And on Jolie’s family’s company.”

I scanned a thread between Riker and Mr. Rhodes, Jolie’s father.

— If we proceed with the licensing deal as discussed, my client expects the previous environmental violations at your plant to remain confidential.

— You understand the implications if they do not.

My stomach knotted. “He blackmailed him.”

“He weaponized information,” Grandma said. “It’s what men like your brother think is the same thing as intelligence.”

“Jolie knows?” I asked.

“Possibly not,” Sullivan said. “Most of these threads are with her father. But if she’s marrying into this, she’s already compromised.”

“Unless,” Grandma said calmly, “she’s in over her head and looking for a way out.”

I thought of her in the hallway, fingers worrying that necklace, voice shaking when she said, This isn’t what you think.

“What’s the plan?” I asked.

Grandma smiled. “Do you know what I regret most about the last forty years?”

“Not going to law school?” I guessed.

“Not hitting your grandfather with his own golf club the first time he tried to cut me out,” she said. “Instead I learned to use the tools the world gave me.”

She tapped a document on her desk. “I’ve executed an amendment to the trust. Lawfully this time. It restores the original equal division. It also creates a safeguard: neither you nor your brother can make unilateral changes without the other’s consent while I’m alive, and after my death, any changes require a supermajority of the board and court approval.”

“In other words,” Sullivan said, “no more backroom signature pages. No more forged anything.”

“And Riker?” I asked.

“Will find out when everyone else does,” she said. “At the wedding.”

“You’re going to blow this up there?” I asked.

“Half the board will be in that ballroom,” she said. “So will the press. Your brother loves an audience. Let’s give him one.”

“And me?”

“You,” she said, “will stand next to me. You will confirm what you saw. You will say out loud that you’re not interested in being the quiet half-share who cashes checks and leaves the mess to the men.”

I swallowed. “What if I don’t want to run the company?”

“You don’t have to run it,” she said. “You have to steward it. There’s a difference. You hire people like him—” she nodded at Sullivan— “to wrestle balance sheets. You bring your judgment. Your ethics. Your spine. That is what this place has been missing.”

Sullivan glanced at me. “She’s right,” he said quietly. “Riker is good at deals. He’s terrible at consequences. You’re the opposite. It’s… useful.”

“I’m a teacher,” I said.

“Who knows how to manage thirty teenagers at once,” he replied. “Trust me, board members are just taller.”

Grandma slid another document to me. My name was at the top.

HARVEY GROUP – INTERIM CO-CHAIR APPOINTMENT

“No,” I said, reflexive. “You can’t just—”

“I can, actually,” she cut in. “As long as my heart is beating, I am the controlling member of the board. This is my last big move. I will not die and leave this empire to a forger.”

“This is insane,” I said.

“So is letting your brother sell the hotels to the highest bidder and turn the family name into a punchline,” she said.

We sat in silence for a moment. The city spread out below the windows, the hotel’s glass reflecting a version of itself I didn’t quite recognize.

“You said Jolie came to see you,” I said. “Has she come back?”

“She tried,” Grandma said. “He keeps getting in front of her. That alone tells me she’s dangerous—to him, not to us.”

“Then we need her on our side,” Sullivan said.

He was right. Jolie had grown up in this world, same as me. She understood the board, the money, the optics. She also understood me in a way nobody else did.

Or had, once.

“Bride wants to meet you,” came a text that afternoon. A number I knew by heart. Rooftop bar at six. No chaperones.

I stared at it for a full minute.

You don’t owe her anything, Sullivan had said when I showed him.

That was the problem. I still felt like I did.

The rooftop was all glass and steel and very expensive plants. Jolie stood by the railing, veil-free, hair up, a drink sweating on the ledge beside her.

“You look good,” she said when I walked over.

“You look like a runaway ad for diamonds,” I replied.

She huffed a laugh. “That bad?”

“That true,” I said.

We stood in awkward silence for a moment, the city humming around us.

“I’m sorry,” she said abruptly. “For everything.”

“You’re going to have to narrow that down,” I said. “There’s a lot of everything.”

“Falling for him,” she said. “Hurting you. Not telling you sooner. Not… trusting you.”

The wind tugged at a loose piece of hair near her ear. I wanted to tuck it back for her. I kept my hands in my pockets.

“I didn’t just ‘fall,’” she admitted. “He pushed. He cornered my dad. He dangled deals we needed and threatened to expose things we couldn’t fix. He made it sound like if I didn’t play along, he’d ruin all of us.”

“And you believed him,” I said.

She nodded. “My parents’ company is hanging by a thread, Mon. Years of bad decisions and looking the other way. When he showed me those emails, I thought—this is it. Someone is going to jail. Someone is going to lose everything. And he said, ‘Marry me and I’ll take care of it.’”

“Not just marry me,” I said. “Stand beside me while I steal from your best friend.”

Tears glittered in her eyes. “I told myself I could protect you from inside,” she said. “That I could push him to be fair. That he was just… angry and scared. But then I saw the way he talked about you. Like you were a problem to solve, not a person.”

“Why tell me now?” I asked. “Two days before the wedding?”

She pulled something from her clutch—a small USB drive. “Because I stole this,” she said. “Copies of everything. The blackmail files. The secret emails. The shady contracts. If you give this to Grandma’s lawyer, it’ll prove what he’s doing. And it’ll tank my father, too.”

“You’re willing to do that?”

Her laugh was ugly and raw. “My dad chose this. For years. Chose shortcuts and look-the-other-way deals. I chose wrong when I chose Riker. This—” she pressed the drive into my hand— “is the first right thing I’ve done in a long time.”

“What do you want from me?” I asked.

“I want you to kill this,” she said. “The marriage. The trust changes. The whole thing. I want you to burn it down and then… maybe someday… forgive me.”

“I can’t promise that,” I said.

“Burning it down or forgiving me?”

“Either,” I said.

She nodded like she’d expected that. “Do you hate me?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And I miss you. It’s very inconvenient.”

She let out a shaky breath that might have been a laugh. “After tomorrow, I’m going to need a lawyer, a new identity, and a therapist,” she said. “Can you help with one out of three?”

“I’ll put you in touch with a therapist,” I said. “And a criminal defense attorney. I draw the line at witness protection.”

She smiled for the first time, small and real. “Deal.”

As I walked away, the USB drive felt heavier than any envelope. Heavier than any ring.

In the elevator, my phone buzzed.

Grandma: How’s our girl?

Me: Terrified. Brave. Armed.

Grandma: Good. So are we.

Part 4

Weddings in my family always looked like movie sets. This one was no exception.

The church was decked out in white flowers that smelled expensive. The air buzzed with polite conversation and undercurrents of gossip. Photos of Riker and Jolie as children—separate, of course, carefully curated—played on screens in the lobby.

I took a seat near the back, where I could see the whole room and be close to an exit. Sullivan slid in beside me, adjusting his tie.

“How’s your wire?” he whispered.

“Unnecessary,” I said. “We’re not trying to send him to prison for the vows.”

“Just habit,” he murmured. “You look good, by the way. Very… heir-apparent meets English teacher.”

I’d chosen a simple black dress and my grandmother’s pearls, which she’d insisted I wear. “Armor,” she’d called them.

The processional music started. Everyone stood.

Jolie appeared at the back of the church in a dress that made the whole room inhale. She looked like a bride in a magazine and a woman walking toward a cliff at the same time.

Our eyes met for a second as she passed my pew. She mouthed, Remember. I nodded.

The ceremony was quick and glossy. Vows that had been workshopped to death. A pastor who enthused about love and partnership and God’s plan. Rings exchanged with shaking hands.

When the pastor said, “If anyone objects,” there was a ripple of held breath. I thought of every movie where the heroine stands up and shouts I do. I stayed seated. Our objections were going to be handled in a different jurisdiction.

“By the power vested in me…”

They kissed. The congregation applauded. Cameras flashed. On some level, I registered that my brother had just legally tied himself to my best friend as he tried to steal my inheritance. On another level, I was mentally marking where the nearest fire extinguishers were.

The reception was in the grand ballroom at Harvey Tower. Crystal chandeliers. A live band playing songs arranged to sound classy. Waiters with trays. A four-tiered cake that looked like an architectural model.

Half the board was there already, laughing into champagne flutes. Investors I recognized from headlines shook my father’s hand. Mom floated from table to table like a very well-dressed ghost, making sure everyone felt seen.

Grandma held court near the center of the room, cane in one hand, champagne in the other. She was in a silver dress that caught the light like armor. When I joined her, she squeezed my fingers.

“USB?” she asked under her breath.

“Thomas has it,” I said. “With a backup copying as we speak.”

“Good.” She scanned the room. “Look at them. Vultures circling what they think is a carcass.”

Sullivan intercepted a waiter and handed me a glass of sparkling water instead of champagne. “Stay sharp,” he reminded me.

“Have I mentioned lately that I hate all of this?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “And yet you’re here anyway. That’s the job.”

The band cut out mid-song. The emcee tapped a microphone. “Ladies and gentlemen, if we could have your attention. The groom would like to say a few words.”

Riker took the mic to polite applause. Jolie stood beside him, fingers on her necklace.

“I’ll keep this brief,” he said, flashing his signature grin. “I know everyone’s anxious to get back to the bar.”

Scattered laughter.

“I just want to say how grateful I am,” he went on. “To my beautiful wife.” He kissed Jolie’s temple. “To my parents, for everything they’ve built. To my grandmother, for being the backbone of this family. And to all of you—for believing in the Harvey legacy. A legacy I plan to protect and grow. For all of us.”

My teeth clenched. He was good. Onstage, he always had been.

“And with that,” he said, “I’ll hand it over to the real boss. Grandma?”

He gestured toward her, patronizing and clueless.

Grandma handed me her champagne flute, took the mic, and stepped to the center of the dance floor. The lights seemed to follow her; they probably did. This was her house.

“Thank you, Riker,” she said. “Always the showman.”

A ripple of knowing laughter.

“I’ll be brief as well,” she continued. “I’m old. People expect us to ramble, but I’ll leave that to your grandfather’s ghost.”

More laughter. She waited for it to fade.

“Some of you have heard murmurs about changes to the Harvey trust,” she said. “About succession. About ‘modernization.’ Let me clarify a few things.”

You could feel the room lean in.

“Thirty-five years ago, my husband and I created a trust that split our estate equally between our son and any future grandchildren. After his death, I added conditions to protect the company from foolishness. Those documents were filed with the court and have governed this family’s business ever since.”

She held up a set of papers—copies of the original trust.

“Recently,” she went on, “someone attempted to alter that trust without my knowledge. To consolidate control in one pair of hands. To cut others out. They even went so far as to forge my son’s signature.”

A murmur rolled through the room like a wave hitting shore. Heads turned toward my father, then toward Riker. Cameras were already out.

“That attempt,” Grandma said calmly, “has failed.”

She held up another document.

“As of this morning, the original equal division is restored,” she said. “Any changes now or after my death require court oversight and a supermajority of the board. No one person—no matter how charming or educated or male—will ever again be able to treat this company like his personal piggy bank.”

My vision blurred for a second. I heard Sullivan exhale beside me.

“Effective immediately,” she continued, “I am naming Monica as interim co-chair of the board alongside me. She will lead with me while I am here and with this board after I am gone. She has the one quality I have found impossible to fake in all my years: integrity.”

People turned, looked at me. I felt heat climb my neck. I didn’t move.

“And for those of you concerned about continuity,” she added dryly, “don’t worry. She’ll still be teaching. We need someone to educate your grandchildren about ethics after all of this.”

Laughter again, but uneasy.

Riker recovered first. He stepped forward, smile tight. “Grandma, with all due respect—”

“With all due respect,” she cut in, “you will sit down.”

There was steel in her voice I had only ever heard once before, the night she’d told a senator to his face that he was a coward.

He didn’t sit. “You can’t just blindside me like this,” he said. “We had an agreement. Dad—tell her.”

All eyes went to my father. He looked at his wife, at his mother, at his son. I saw the moment something in him tipped.

“No, son,” he said quietly. “We had a misunderstanding. You thought my inattention was permission. It wasn’t.”

The emcee’s mic squealed. The sound was terrible and perfect.

“Furthermore,” Grandma said, raising her voice slightly to carry, “the board has been made aware of certain… irregularities.”

That was Thomas’s cue. He stepped up from the edge of the crowd, a manilla envelope in hand.

“We have evidence of attempted fraud,” he said. “And of unauthorized use of confidential information against business partners. This information has been turned over to the appropriate authorities.”

I watched the color drain from Riker’s face.

“This is insane,” he said. “You can’t do this at my wedding.”

“You chose the theater,” Grandma said. “Don’t complain now that the show isn’t going your way.”

Jolie moved then. She stepped up to the mic, hand shaking, necklace glinting under the chandeliers.

“I have something to say,” she said, voice wobbling.

Riker hissed her name. “Jolie, don’t—”

She looked at him, then at me, then out at the crowd. For the first time all night, she looked like herself.

“Riker blackmailed my father,” she said, each word gaining strength. “He threatened to expose environmental violations at our factory unless my family signed unfair contracts and helped him pressure his own. He told me marrying him would ‘fix everything.’ It hasn’t. It’s just hurt more people.”

Gasps. Someone swore softly. The band in the corner looked like they wished they could vanish into their instruments.

“I went along with it,” she continued. “I thought I could protect my family and my friend at the same time. I was wrong. I’m sorry.”

She stepped back from the mic. Riker grabbed her wrist.

Cameras flashed. Security moved. So did Sullivan, intercepting him with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes.

“You’re causing a scene,” my brother snarled.

“You started it,” I said.

The rest of the night was a blur of sirens and statements. The police didn’t arrest Riker on the dance floor; this wasn’t a movie. But they did escort him to a side room, and when he tried to leave with a briefcase, they took it.

Reporters set up outside the hotel, their breath puffing in the cold, lights harsh. Grandma gave a short statement. “The Harvey family will cooperate fully,” she said. “Our legacy has survived wars and recessions. It will survive this. We will be better for rooting out rot.”

Dad sat in a chair in Grandma’s office afterward, looking ten years older. Mom came in and sat on the arm of his chair, futilely smoothing his hair.

“I failed you,” he told me.

“You failed yourself,” Grandma corrected before I could speak. “But you’re not dead yet. You can learn.”

He looked at me, eyes glassy. “I let him run wild,” he said. “I assumed you’d be fine without my attention. You always were. That’s not fair. It never was.”

I sat across from them in the chair that had always felt too big and felt it fit a little better. “We can fix some of it,” I said. “Not all. Some.”

Later, in the quiet of my apartment, Sullivan dropped onto my couch, tie loosened, hair a mess.

“Well,” he said. “That was the worst wedding I’ve ever been to. And I went to one where the groom passed out in the cake.”

I laughed, then cried, then laughed again.

“You did good,” he said softly.

“So did you,” I replied.

He nudged my foot with his. “So,” he said. “Co-chair.”

“Interim,” I corrected.

“For now,” he said. “How does it feel?”

“Like jumping off a cliff and discovering halfway down that maybe I have a parachute,” I said.

He grinned. “That sounds about right.”

Part 5

The fallout took months.

White-collar crime isn’t fast. There were investigations and subpoenas and interviews with serious people in serious rooms. Lawyers billed hours I didn’t want to think about.

The USB Jolie had given me turned out to be a treasure trove. The U.S. attorney’s office loved it. The SEC loved it. The environmental regulators salivated.

Jolie’s father negotiated a plea deal that left him without a company but not in handcuffs. He started teaching business ethics at a community college, which the universe clearly chose for the irony.

Jolie herself pleaded guilty to a minor charge—misprision, her lawyer called it—for not reporting things sooner. She got probation, community service, and therapy mandated by a judge who clearly had a daughter.

We met for coffee one afternoon at a quiet place across town, both of us wearing sunglasses like we were hiding from paparazzi instead of PTA moms.

“How’s community service?” I asked.

“I’m cleaning up riverbanks,” she said. “Waders, trash bags, the whole thing. It’s weirdly cathartic. There’s something satisfying about pulling something rotten out of the water and knowing it’s not hiding anymore.”

“Fitting,” I said.

She ran a finger around her mug. “I don’t expect you to forgive me,” she said. “Ever. But I’m going to spend a long time trying to be the kind of person you would have trusted if none of this had happened.”

I believed her. Not entirely. Not yet. But enough.

“The foundation needs a compliance director,” I said. “Someone who knows how to spot messes early. Someone who is very, very motivated never to miss a red flag again.”

Her head snapped up. “You’d hire me?”

“I’d hire the version of you that understands exactly how badly people can screw up and how much it costs,” I said. “Do you know anyone like that?”

She smiled, small and watery. “I might,” she said.

Riker pled guilty eventually. Two counts: attempted fraud and misuse of confidential information. Eight years, the judge said. With good behavior, maybe less. Enough time to sit with the reality that he was no longer the golden boy.

I didn’t attend the sentencing. I read the transcript later. The part where the judge told him, “You’re not here because of one mistake. You’re here because you believed the rules didn’t apply to you,” felt like something carved in stone.

Grandma stepped down from the board six months after the wedding-that-wasn’t. “I’m tired,” she said. “And daytime television is not going to insult itself.”

We threw her a retirement party that doubled as a rebrand. Harvey Group 2.0, the brochures said. New ethics guidelines. New whistleblower hotline. New sustainability initiatives. New wallpaper in the second floor ladies’ room.

“You changed the wallpaper,” she said approvingly at the unveiling. “That alone may save us.”

I kept teaching. Three sections of American Lit and two of Creative Writing. Teenagers still turned in essays late and fell in love with the wrong people and rolled their eyes at Gatsby like he was an influencer.

On my “off” days, I went to the office. Sat at the big table. Learned how to read a balance sheet properly. Asked uncomfortable questions in board meetings. Pushed through profit-sharing plans for hourly staff.

“We’re not a charity,” one board member grumbled.

“We’re a hospitality company,” I said. “Pretending our house isn’t on fire doesn’t make guests sleep better.”

Sullivan became CFO officially. He wore suits more often and sneakers less, but he still brought me coffee exactly how I liked it and still texted me memes during long calls.

One night, late, we were the last two in the boardroom. Spreadsheets open, takeout containers between us.

“Did you ever imagine this?” he asked, gesturing around.

“Me, here?” I said. “No. You?”

He grinned. “I always assumed I’d end up crunching numbers for some soulless conglomerate,” he said. “This is much more chaotic.”

“And the company?” I asked. “Are we going to make it?”

He leaned back, eyes on the skyline. “We’re not going to be the biggest,” he said. “Not with how we’re choosing to do things. Paying people fairly, not cooking the books, not bribing zoning officials—it’s not the fastest path to world domination.”

“Good,” I said.

“But,” he added, “we’re going to be around a long time. I can feel it. The numbers are starting to line up with the values. It’s… weird.”

“Like the universe is rewarding us for not being trash,” I said.

“Something like that.”

We sat in companionable silence for a while.

“My grandmother did the hard part,” I said eventually. “She yanked off the mask.”

“You did the hard part,” he countered. “You stayed. You didn’t run away to some beach and live off dividends while everything burned.”

“You say that like it wasn’t tempting.”

He laughed. “The beach will still be there when you retire.”

On the one-year anniversary of The Wedding, I found the original invitation in the junk drawer where I’d shoved it. The photo of Riker and Jolie in that field looked like a postcard from an alternate universe.

I took it to Grandma’s. Showed it to her at the kitchen table while she did a crossword in pen.

“What a waste of cardstock,” she said.

“Do you ever feel bad?” I asked. “About how it went down?”

She considered. “I feel bad that I didn’t fix the culture sooner,” she said. “That I let men around me treat women as accessories and money as absolution for too long. That I let your brother grow up thinking charm and talent were enough.”

“But about him?”

She shook her head. “He took his shot at the crown,” she said. “He missed. Life has consequences. The best thing we can do is make sure we don’t turn into him while we hold him accountable.”

“Inspirational,” I said dryly.

She smiled. “Are you happy?”

It was the second time I’d been asked that question in as many years. The answer felt different now.

“I’m… tired,” I said. “Busy. Worried. Hopeful. Some days I want to move to a cabin in the woods and teach raccoons to read. But most days… yes. I’m happier than I thought I’d be.”

“Good,” she said. “Then the trust is doing what it was supposed to do. Trust is not about money, you know. It’s about who you become when you have it.”

A few months later, she died in her sleep at eighty-seven, a pen on her nightstand and a book on her chest. The funeral was televised. “Matriarch. Visionary. Force of nature,” the chyron on one network said.

In her will, she left me her pearls, her office chair, and a letter.

Monica,

You thought I chose you for this because your brother was bad. That is not why. I chose you because you know the difference between fairness and gentleness, between kindness and weakness. Because you understand stories. And because you will never forget that this is not about you.

Take care of the people who change the sheets and scrub the toilets and work the night shifts. The empire will take care of itself.

Love,

Grandma

P.S. Don’t let Sullivan talk you into any more ugly lobby art.

I cried until my eyes hurt and then took the letter to the office.

In the hallway outside the boardroom, someone had already hung a new photo. Not of me, not of a building. Of Grandma, standing at a podium, head thrown back mid-laugh, a caption underneath:

Rosaline Harvey, 1938–2025.

The reason you’re still here.

I touched the frame lightly. “I won’t screw it up,” I promised her.

Years passed. We opened hotels in cities that needed jobs, not just Instagram stories. We funded scholarships. We cleaned up riverbanks.

Payton—my niece, born to everyone’s surprise two years after the wedding-that-wasn’t, from my brother’s ex-girlfriend who wanted nothing to do with our money—grew up with my last name on her backpack and my grandmother’s stubbornness in her jaw.

Sometimes, when she comes to the office after school and sits in my chair, feet not touching the floor, she asks, “Is it weird that you’re the boss?”

“Yes,” I tell her. “And no. And it’s your turn next if you want it.”

She considers this gravely. “I might be a vet,” she says. “Or the president. Or a poet.”

“You can be all three,” I say. “But if anyone ever forges your signature, call me.”

She rolls her eyes. “Obviously,” she says.

At night, when the building is quiet and my office is just a rectangle of light in the glass, I sometimes think back to that first envelope. That heavy cream card with the gold letters and the smiling faces.

My brother married my best friend and tried to take my inheritance.

He failed.

Not because I was smart enough or ruthless enough, though those helped. But because Grandma stepped in and refused to let his version of the story be the final draft.

The money stayed where it was meant to be. The company evolved instead of exploded.

And I, the “sensitive” little sister with an English degree and a high school classroom, became the woman who could read a contract and a room with equal fluency.

If there’s a moral, it’s this:

Never underestimate an old woman with a trust, a granddaughter with a spine, and a stack of documents you actually read.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words…

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words… …

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming!

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming! Part 1 On my…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He Said Inside…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every Word…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every…

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me!

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me! Part…

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry …

End of content

No more pages to load