My brother-in-law assaulted me — bloody face, dislocated shoulder; my sister just said “You should’ve signed the mortgage.” All because I refused to be their guarantor I dragged myself to my parents’ door, begging for help then collapsed. What happened next even the police were horrified…

Part One

Blood tasted like pennies and regret. It pooled in my mouth before my head finished registering the fall. The carpet pressed into my cheek, fibers sticking to the wetness on my skin, and when I tried to move my right arm the world replied with a thunderous lurch of pain that made the breath leave my lungs in a single, animal gasp. The room spun. He was standing over me, shoulders wide, breath loud; the outline of his face blurred by all the things I couldn’t focus on: the bruise blooming along my jaw, the split at the corner of my lip, the unnatural angle of my right arm.

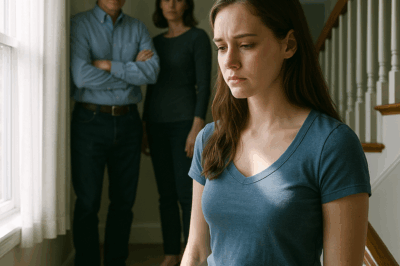

My sister did not scream. She did not reach for me. She only folded her arms in that old, brittle way she had when she wanted to show she wasn’t wavering, and she said, like she was naming a lost mitten, “You should’ve signed the mortgage.”

I have re-lived that sentence a thousand times. Each replay is a slower, more deliberate excision. It’s not that my sister was cruel at times before—she wasn’t that simple. She had been my early shield; she chased away bullies for me at eleven and learned how to braid my hair without me having to explain. She bandaged skinned knees when I tripped on the gravel in our childhood yard. We’d built pacts in the dark: secrets of scraped knees and stolen candy, a belief that we would always be on the same side. So her words that afternoon—spoken from across a room while my blood mixed with carpet—felt like something amoral and new, as if whatever small code had kept us sisters had been negotiated away for convenience.

The reason for the assault was a domestic minor/major: a mortgage and a guarantor. My sister and her husband had been trying to buy a house for months; the bank wanted a guarantor for the loan. They had asked first—little loans, then bigger ones. They’d framed it as a temporary trouble at first, a hiccup with the contractor, a delayed invoice from a client. They had said the bank would be easier if I just signed the papers. They promised quick repayment and baked goods. I refused.

I said no because I’d watched marriages slide into the shape of other people’s expectations. I’d watched my own savings become a sanctuary of the life I was building. I was not rich; I had simply been pragmatic. The day I refused, their smiles thinned. The requests became heavier the longer I held my ground: a subtext of “family owes family,” the unspoken shaming that often disguises itself as loyalty. When I refused a second and third time, their voices changed tone. “You’ll regret it,” he said once late at night, the house around us thick with summer heat. My sister shrugged then, as if to signal it was a thing to be endured. Later, she would say she was tired. Later, she would say she never thought he would do this.

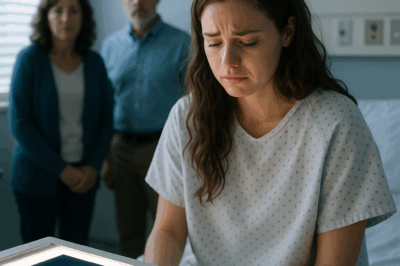

I remember staggering to my parents’ door with a cloth pressed to my face, the world boiling into tunnels and edges. My legs were drunken pillars. I rang the bell with numb fingers; my parents opened to the sight of me—one arm useless, my shoulder laughing at an unnatural angle—blood dark on my blouse. My father froze like a man who’d seen a terrible play unfold at the kitchen table; my mother’s face crumpled into a sound she could not name, a human thing that is part sob and part animal grief. I put one hand to my chest and said, “Please. Help,” and then the room faded into black.

When I came to, the flat fluorescent light above my hospital bed hummed like a distant desert. A nurse’s voice softened the corner of the room. My jaw had been set with wires; everything that could be put back in place had been put back. One arm was in a sling. The other fingers were numb with trauma. Pain came like waves; each crest demanded focus. The doctor spoke carefully about dislocation and physical therapy and a prognosis that contained words like “months” and “partial recovery.” There were reports, forms, and the small cruel etiquette of logging violence: “Did you want to press charges?” they asked, and I said yes because there was no other honest answer. I said yes because my bleeding body had taught me that silence is a velvet cage.

What I had not expected was my sister’s answer when I phoned her from the hospital. I thought there would be at least shock, an apology, perhaps a promise to make him leave. Instead the line hummed, and she said a string of blank things like “I’m sorry you’re hurt,” followed by a practical, iron sentence: “You should have written your name on the mortgage form.”

I couldn’t hear her after that. The world became a partial narrative tape I played in slow motion, holding everything up to the light: the way a home can be an economy as much as a sanctuary; how love and debt are sometimes used as interchangeable verbs; and how people will posture for protection while committing small cruelties. The bruise along my cheek thawed into an angry purple; the wire in my jaw clinked when I swallowed.

Pain teaches a peculiar attentiveness. In the months after the hospital I learned to focus on those details that matter for the lives that proceed: the tremor in the voice of the bank manager when he said “suspicious activity,” the faint rustle of legal pads hidden in their study, the sly way his email subject lines changed when he thought I wasn’t looking. I studied while my body knit itself anew. I listened more than I spoke. I learned that revenge in stories is usually loud, but actual reparation is quiet and awful and requires people to keep breathing while they do hard things.

The first part of my plan involved silence. People lower their guard when they think the other is broken. For a long time after the assault I let them believe I had been scattered by the event, that the person who once contested their demands had been reduced. I didn’t argue any more when they superficially tried to soothe me. I accepted blandments from them in the same way one tolerates a draft—because it was safer, because planning needs obscurity. I let them think I had given up.

In truth, I had not. I used those weeks to stitch together a map of their finances. I discovered things by accident and by design: a pattern of small cash transfers from a company he owned to a set of shell accounts in slightly different names; an invoice trail that didn’t add up; a contractor who insisted on cash payments and who could not produce receipts on demand; evidence that a few “consulting fees” were being laundered through corporate expenses; and, most damning, alterations in my parents’ account files that suggested my sister had been living beyond the income she declared. The more I dug—the hours spent propped with a laptop in that half-light between sleep and the day’s beginning—the more it seemed their house sat on a foundation of little lies disguised as economic necessities.

The middle phase of the plan was infiltration. I went to the companies he dealt with in small, polite ways. I asked questions as a neighbor might ask. “Do you remember when the plumbing started?” I would say casually, and watch the answer like a fish strike. I used the pretense of wanting to coordinate a community picnic to get information from the contractor. I asked the bank for records in the name of helping my parents; they asked for authorization, and I produced what I needed, having learned the art of paperwork in the dry weeks after the hospital. Whatever we do for ourselves in a crisis often shapes the tools we will use—my incapacity forced me to choose methods that were not flamboyant but meticulous.

My sister was careful in the ways of denial. She had rehearsed her lines: “We’re under pressure,” “It’s a temporary fix,” “You’ll help us and we’ll pay you back.” Her lies were thin threads and will snap when pulled. He—my brother-in-law, with his loud laugh and his hands that could have been strong enough to hold a child—was clumsy. He tried to cover, but the arithmetic of their debts was not human. Paperwork is cruel; it testifies when tongues are unreliable.

I gathered everything into reddened folders. Bank statements, ledger copies, emails he’d forgotten to BCC, testimonials from workers who had been paid under the table, and a trail of forged signatures on documents that had small inconsistencies—tiny differences in the curls of letters that a handwriting analyst would spot with a stony little joy. I hired, modestly and secretly, a forensic accountant. Their eyes on those documents were the same as mine—small, pleased, sharp. “This is not simply poor bookkeeping,” he said. “It’s organized misrepresentation.” When he said that my mouth made a small, private sound of satisfaction that felt almost like sobbing.

When the weather changed to the day of reckoning, I walked into their house as if I were only going for tea. I carried the surgical lightness of someone who has rehearsed neutrality. My arm was stronger now; my jaw had been freed from its wires. I was allowed by the world to be present and not wild; the world often expects the battered to be demure. They were not expecting me.

Their study smelled of coffee and printer fumes. The space where bills had been spread became a stage of guilty things. He was at the table; his face was the color of someone who had slept poorly. His hands trembled when he saw me. My sister’s phone flickered like an insect with every new message. The room seemed to contract around those little vibrations—creditors, a tax investigator’s email at the top of the list, a text that said “we’re auditing his company.” He looked up, and for a second his jaw found the line of a man who believes insurance will be his default. Then he saw my face.

“You did this,” he spat.

I made no move to deny it. There wasn’t much theater for me in that moment. I felt the stitches along my jaw, the tender ache in my shoulder; I let those things be my credentials of pain and of correctness at once. “Yes,” I said simply. “I did what I had to do.”

My sister began to cry, a wet, brittle sound I recognized in its honesty; it was the sound of someone surprised by the consequences of their own choices. But there was also something else: calculation, the silted kind of rationality people use when they count up losses. “Why?” she said between sobs. “Why would you do that to us?”

“Because you hit me,” I said. “Because you think my signature matters more than my life.”

The police arrived like a winter dawn—insistent, efficient. They did not come because of a dramatic appeal but because the paperwork I had filed months earlier had ripened into actionable things. Fraud is not always a siren; sometimes it’s the slow accumulation of evidence, a quiet crescendo in a prosecutor’s office. They swept the room with their steady motions. I watched their faces change as the investigators leafed through the files I’d given them. The first look was one of misplaced curiosity. The second look—the one that made the hair lift on the back of my neck—was horror because the trail was larger than any of us expected.

He, my brother-in-law, had not been merely juggling small debts. The documents showed a web: falsified invoices, misdirected project payments, and a network of phantom subcontractors. He’d used company funds to pay off personal expenses, opened lines of credit using forged references, even used my parents’ names—quietly, ingeniously—when he needed to paper over an unpaid tax invoice. The detective read the handwriting comparisons and then looked at me like a man who had discovered something more dangerous than a petty conman. “This is organized fraud,” he said. “This is criminal embezzlement.”

My sister sank lower into her chair, as if gravity had a stronger claim on her than before. “We’ll pay it back,” she said, words coming faster now, as if quantity could be a substitute for repentance. “We can—”

“You signed things that were not yours,” the detective said. “You introduced your husband’s shell companies into your parents’ accounts. You used forged letters. These are not things credit scores can fix. These are things a court can handle.”

I had expected legal processes; I had not expected to watch my sister collapse the way she did. There was a perfunctory request to have them step aside while officers took photocopies and statements. My sister—who had once offered me her Easter chocolate and told me that her loyalty was the future compass I could rely on—begged the officers to show mercy. She cried and promised, and her voice broke into a small ledger of excuses.

As the handcuffs closed around him, my brother-in-law cursed. He spat out versions of how I had betrayed him, how the family had been under pressure, how he had always meant to pay things back. The detective’s expression was blank. Crime is often a homicide of moral imagination; the perpetrator rationalizes until they can live inside their own rationalizations. He did. But rationalization does not erase the line of signature forgery or the invoices stamped with dates that could not be true.

My sister’s words in the hallway as he was led away have a way of staying with me. “They don’t understand,” she said, mouthless with grief and fear. “We wanted a life. We—”

“Wanted to build a house on shaky ground,” I said.

Her eyes met mine briefly. I don’t know what she expected: forgiveness at the end of violence, or perhaps that I would shrink away so she could stitch the rest of her life with her husband’s thread. There was perhaps a sliver of calculation left in her gaze—how to salvage, how to keep a portion of what is left. She began to bargain with small things, calling the prison counselor, pressing her case into the hands of lawyers who specialized in family law and in cleaning up fraud. The officers had the small joy of duty; the bank had the small joy of sending registered letters; the tax office had the small joy of lining up interviews.

On my walk home after signing statements and repeating the night’s script to detectives who had an impossible amount of paperwork ahead, the city felt like an organism that had turned and looked. The air tasted different, like a place that had made one small act of justice—slow and necessary and unsentimental. I had no idea if this would fix what was broken inside me. The stitches in my face ached; the muscles that had been torn screamed in the nights. But there was a new lightness in the way my bones handled life. I had done the honest, unglamorous work required to unweave their deception.

Part Two

The months after the arrest were fogged with paperwork and a new, cerebral kind of pain. The police investigation widened its scope and so did the scrutiny at home. My parents—who had frozen when I first collapsed at their threshold—had their world upended by court summonses and by the unsettling discovery that their only child’s marriage had been an instrument in a financial net. My mother would stand in the kitchen in the mornings and hold a mug with shaking hands, listening to the radio even though she disliked morning chatter. My father retreated into silence that smelled like old tools and accounts books, the kind of silence you get from men who think their function is to bear burdens without complaint.

The trial took place in a municipal court with the hush of public tragedy. My brother-in-law, who had once been loud in his assertions and acrobatic in his excuses, sat smaller in the dock than I expected. Perhaps prison diminishes before it begins. Perhaps facing a public ledger of crimes reduces bravado into a slow internal weathering. He had been a man of charm; now he gave off the scent of someone much smaller.

The evidence we collected—handwriting analyses, bank transfers, emails—shone under the fluorescent lights like an indictment of their whole life’s shape. The forensic accountant’s testimony was the quiet Fibonacci of dwindling defenses. “The patterns are consistent with organized embezzlement,” he said for the record, speaking in crisp, unsentimental English. “This is not a single error in bookkeeping. It’s a repeated, intentional misallocation of funds incompatible with honest business practice.”

Those were the words that made the judge lean forward, watching the faces of those in the room. My sister’s lawyer argued that she had not been aware of the precise mechanisms; she had believed her husband and had been manipulated. That is a legal corner: many spouses are sincere in their ignorance, and the law sometimes must weigh whether a partner was complicit knowingly or simply coerced by trust. The slides of our case were complicated. We had proofs of signatures on documents my sister claimed she had never seen. We had witness statements of late-night phone calls where she had been promised certain payments that never occurred. Complicity is a gradient, not a line.

He was found guilty on multiple counts—embezzlement, fraud, and a handful of charges that are the particular lexicon of those who steal money in palimpsest. The sentencing was more of a procedural narrative than dramatic. He would be jailed for a period that felt proportionate to the ledger he had carved out of lies. The judge’s voice when it announced the sentence was not triumphant; it was pragmatic. Queues of human consequences unrolled behind the statements: children’s bank accounts frozen, mortgage contracts in dispute, lenders readying themselves for legal remedies.

My sister’s fate was trickier. The court recognized elements of coercion mixed with self-deception. She had been granted leniency in a sentence that instead asked for restitution plans and community service. She would have to wash back the stains of what she had done with steady work: a financial oversight course, mandatory familial counseling, and a full accounting of the funds she had used. The judge said something that could have been a benediction: “The law seeks not only to punish but to encourage restoration where possible.” I folded up that line and kept it like a small, damp cloth.

There was more. The police were horrified in a way I had not foreseen. They found, in a battered shoebox in a drawer that my sister had left unlocked, letters from other women—small notes and pleas for payments, records of favors night after night for which someone had promised the earth but given only paper. There were charred records, a ledger half-burned in the fireplace where they had tried to make themselves above scrutiny. That particular find—papers in embers—made the detective on the case mutter in a way that sounded to me like the heavy breathing of a man who has found a corpse he hadn’t expected. He said, “They tried to burn their tracks,” and for a moment all of us in the room understood there is a point at which hiding makes the hiding itself a crime.

I had not anticipated the way institutions would respond: bank freezes, credit holds, the sneering corrective letters from lawyers whose text read like blunt instruments. I had not expected the corporate consequences to ripple into their relations with others—small contractors who had been paid late, construction firms who had been ghosted. These were people who had not done wrong but had been harmed by the ripple of a bad marriage.

My family suffered reputationally in our small town. The neighbor who brought over a casserole once watched me with pity in his eyes. People asked me if I felt guilty for “ruining” a family. They were trying on language that didn’t fit the shape of truth. I was not a proud person to rejoice in broken families. I had simply done what I believed necessary. The people who had choices had chosen to sell their intimate loyalty for the bland currency of credit.

Healing, for me, was less about poetic closure and more about patience. The physical wounds healed in the prescribed measures—physio, a dramatic improvement of the shoulder’s range, the slow whitening of scars. Emotionally, I found shelter in therapy rooms with wide windows and kind clinicians.

In therapy I learned to name the self I had suppressed so long: the one who had said no, the one who would not lend her signature as if it were a blank check for the next time someone wanted to gamble recklessly with family security. I also learned to feel without immediate response. My sister visited the rehab center once, and her face was a portrait of someone who’d been reduced by consequences. She had lost her house, for a while at least; contacted by lenders who put pressure on her, she had to learn to be humble before her error.

We had a conversation in the kitchen once that was not cinematic. She apologized, not for the whole of her life (there are things apologies cannot actually mend) but for the specific acts that had broken me. “I was scared,” she said. “I was greedy.” The sentences were simple. They fit into the shape of reparations: she agreed to surrender any small assets she had that had been obtained through the fraud, to work part-time assisting an accountant on his ledger work, to serve in a community center.

I forgave her in the way a person forgives someone who has been injured and who must now be helped into the day again. Forgiveness does not mean rebuilding a bond to what it once was; it means giving rest to anger so it doesn’t grow roots. In practical terms, I agreed to help my parents navigate the legal side of the mortgage and settlement; I used my modest portion of the funds I’d been given through restitution to help bail everyone out of the small, suffocating financial traps they had been shoved into. I did it with the sternness of someone who would not be taken advantage of again and the compassion of someone who had been saved by slow kindness.

We did not return to who we had been. The family’s architecture changed irrevocably. My sister’s marriage ended in the dock. My brother-in-law was sentenced to a term that included both incarceration and mandated restitution; when he left the courtroom his jaw collapsed like a man who had given his last claim to dignity in pursuit of reckless convenience.

There were moments of raw, public discomfort. At a grocery store months later he stood in the cereal aisle while a woman I recognized—one of his former subcontractors—voiced a small coin of truth about the damage he had done to her business. He held his head down. I watched him, and there was a deep, sober feeling: not vindictive but oddly serene, like someone who is now made to face all the invisible debts their impulsive spending had incurred.

Meanwhile, life edged toward a deceptively steady routine. I returned to work part-time at first and then full-time because work is a place where one can re-knit a life. I threw myself into small, daily labors: waking early, preparing breakfast, paying attention to the therapist’s suggestions: grounding exercises, naming the emotions by color, limiting my exposure to people who spoke in old patterns of shame and blame. I learned to let the small graces—coffee at six, emails that concluded with a friendly sign-off—be part of a slow recovery program.

My parents’ house became our new center for public conversation about money. We convened a meeting with a financial counselor and a lawyer who helped my parents rewrite their estate to ensure that nothing like this could be used again as a tool for coercion. The process of reconfiguring a life after betrayal is administrative: you change passwords, you audit transactions, you decide who has what. There is a dignity to it too; it is a moment where you take power back by doing the small, precise work that keeps a household above water.

People sometimes ask if I regret the violence of it all. I do not. I do not relish violence. I do not take joy that someone was beaten and had to be hauled to a hospital. But the truth is a ledger: his assault carved into my face the proof that no one is entitled to the skin on another’s life. There are moments when the story we tell ourselves shifts from “I was a victim” to “I was someone who did what was necessary.” I choose the latter. I choose to be the person who saw a pattern and unraveled it, who chose the slow, complicated legal route instead of a returning violence of my own.

Years passed. The sentence served its time and then the release came for him—paroled, older in a way that seemed rawer. He tried, awkwardly, to contact me as people sometimes try to patch over small rivers of past wrongs. He wrote a letter that contained kind words and apologies, and a hope that I might see him as reformed. I read the letter on the bench of my favorite park, where the river moves in folds the color of an old coin. I did not respond. I had learned not to be generous in ways that tricked me into being smaller.

My sister wrote less frequently. When she did, she asked for small updates about our parents. She asked if I would help her find a job where she could learn some modest competence in accounts rather than desperation. I agreed to assist if she were still sincere. The ledger of our lives now held different entries: forbearance offered, limits carefully explained, and a slow, mutual responsibility to make good what had been broken.

I started speaking publicly about what had happened—first in a small support group for survivors of domestic assault, and later at a legal clinic where people learned how to protect themselves from financial abuse. There is an odd, steadying power in using your voice: it catalyzes people and gives the fearful a method to be heard. I experienced, through those sessions, a rarer kind of justice: people’s gratitude not because I had achieved vengeance but because I had turned my experience into a map for others who might be broken in similar ways.

The police remained in contact, sometimes for small updates, sometimes to check in on how restitutions were being carried out. I smiled and gave them small updates; they had been horrified by the depth of the ledger they had found, and horror had a professional weight that was hard to shed. They were, in their slow procedural manner, satisfied that the law had done its job in the way the law can: it tried to undo harm and to fix the small parts of the damage.

In the end, the police’s horror receded into an ordinary memory. The greater consequence had been personal and domestic: we had rebuilt our family across a new architecture of truth-telling and legal clarity. My parents learned to distrust blurred statements and to insist on receipts. My sister learned to value errands of honesty more than the dangerous pressure of appearing prosperous.

And I—my cheek still carries faint, pale scars you can see if you look closely. My shoulder occasionally stiffens when the weather takes a cold turn. But the thing I have most clearly is a rhythm of days. I wake, make coffee, sometimes go to the bank to help an elderly neighbor sort out a confusing statement. I teach two hours a week at a clinic where I explain to people how to keep their finances in their own names, how to spot the tiny, slippery signs of forgery and coercion. I keep my eyes open. I am vigilant, not brittle; generous, not naive.

People ask how I survived it all. My answer is less heroic than people want: I survived by refusing to be small in the face of violence. I refused to let someone else make my signature the blank currency of their cruelty. I refused to let the assault name me for the rest of my life. I learned the language of ledgers and of legalese. I turned my bleeding into proof that I would not be bought or scared or quieted.

If there is a single, clean ending to this story it is the way our lives continue after the noise. My brother-in-law served time and then lived a diminished life; my sister works in a clinic where she helps with clients’ appointments, small reparations that have a daily dignity. My parents live in a home that is safe from financial breathing. The police, who once opened their folders and were horrified, eventually filed the last report and put the case to rest. I still go to the park sometimes and watch the river fold. The final thing I learned is that horror is a human tool as much as kindness; it wakes a sleepy world long enough for justice to be applied. But justice is not the end of the story—it is only the stern beginning of rebuilding a life that is not defined by the violence inflicted upon it.

When people say the word “family” now, I see the skin as well as the ledger: the softness and the danger, the way you can be loved and exploited by the people nearest to you. I learned to be cautious without being closed, to be tender without being weak, and to use the quiet accumulation of evidence rather than the loud accumulation of fury.

There is a surety to life after harm. It is not a miraculous recovery. It is work—tedious, slow, mundane—and sometimes it includes teaching others how not to be so easily consumed. I tell my story to people who need to hear it because I want them to know there are tools that exist outside of silence: law, community, forensic accounting, brave friends, and the plain courage to say no when someone asks you to risk everything for a promise that is obviously a lie.

Once, when winter made the park shimmer, my sister sat across from me on a bench. We were not the sisters of childhood anymore; we were acquaintances who had shared, painfully, the architecture of an error. She reached for my hand—not awkwardly now but cautiously—and said simply, “I’m sorry.” I nodded. She then said something else: “I wish I’d been braver. I wish I’d defended you.” We sat in the winter sunlight and let the aching be shared in small measures. It wasn’t redemption and it wasn’t a miracle. It was a sentence that fit within our lives: an apology, accepted imperfectly; a hand held for a moment; and the long, honest work of building again.

There was no triumphant final moment, no dramatic redemption arc where everything is clean. Real life does not tidy itself like that. What I had—what I still have—was steadier. Small compensations: my parents’ pride when I led a financial literacy class, the way my neighbor calls me to help him balance his books, my own sense of a life maintained rather than consumed. The police were horrified once by what they found in a shoebox and by the web of forged letters and phantom invoices. They did the work they could. I did the rest.

If you asked me today if I would sign the mortgage for someone I loved even if they asked politely, my answer would be cautious and layered with all I have learned. If you asked me whether I regretted refusing to sign that day, I would say yes and no: yes, because I lost simple things—my sister’s trust in the way I hoped to keep it—but no, because that refusal saved me from something larger. I saved myself from being the pad upon which someone else wrote their reckless handwriting.

Life moves forward. The bruise fades. The ledger remains. The quiet daily acts of honesty and the small ceremonies of generosity are how we rebuild after a person with a loud voice and a small conscience has taken their due. I am here; my arm functions, my jaw heals more each year, and I have turned the horror into something that can help others step out of silence. The police were horrified once. The rest of us learned to be vigilant, to ask for receipts, and to say “no” when people we love ask us to risk everything. That is the clearest ending I know: not vengeance, not celebration, but survival and careful repair.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing. CH2

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing Part One Stop. Stop, stop—you’re…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

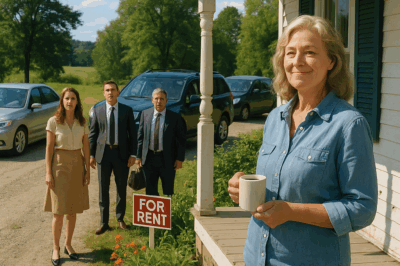

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER BROKE MY RIBS. MOM WHISPERED, “STAY QUIET -HE HAS A FUTURE.” BUT MY DOCTOR DIDN’T… CH2

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

End of content

No more pages to load