My Brother Got a Car for Graduating. I Got a Bill for Rent. I Left, and Now They Want Me to Return

Part One

My brother got a BMW for graduating with a 2.3. I got an invoice for back rent on my childhood bedroom the same week I graduated summa cum laude.

“Time to be independent, sweetheart,” my mother said, sliding the folded paper across the kitchen island the way dealers slide losing cards. My father nodded like a foreman approving a pour.

Two years later, at a client appreciation dinner in our small Minnesota town, two hundred clients would watch their empire collapse into the dust it had been built on—because my grandparents’ legacy couldn’t survive another year of fraud disguised as family values. Not after the managing partner at my firm, Richard Sterling, quietly handed me the lever I needed to move a mountain my parents thought would never budge.

My name is Paige Harlo. I’m thirty-one. And the night I decided to stop being the family fixer and start being the family’s reckoning, the lake outside my apartment froze hard enough to hold a car.

I grew up in the shadow of the company my grandfather, Frank Harlo, built with blueprints under one arm and a Thermos under the other: Harlo Construction. He poured footings in spring mud, framed roofs in winter winds that made his eyes water, and taught men twice his size to check their measurements twice and their pride three times. In the lobby of our office, a black-and-white photo shows him in suspenders grinning at a bricks-and-mortar horizon he’d earned from nothing but a loan, stubbornness, and a ledger kept clean enough to eat off.

My parents inherited that ledger and used it to wipe their hands after every indulgence.

My brother, Marcus, is four years younger, with a smile that earned him extra cookies whenever the church ladies brought casseroles. When we were sixteen and twelve, respectively, I spent a summer slinging eggs and coffee at a diner to save for a 2004 Honda with a leaky window and a tape adapter for a phone I wasn’t supposed to have. The same week I brought it home, Marcus took my father’s new motorcycle around the block to impress girls with bangs and tank tops and slid it into the Jensen’s picket fence. Not a scratch on him. Plenty of white paint on the chrome and my father’s face.

Punishment? “Let’s get you a safer ride,” my mother said, and three days later a nearly-new Mustang glowed in our driveway like a showroom had sprouted on our cracked asphalt. When I asked where my applause was for saving every tip, my mother said, “Boys need stability more than girls do,” like it was scripture. The sting was my fuel for years.

In college I won a full ride, three campus jobs, and a caffeine addiction. Marcus got $45,000 a year for a private school he left as often as he attended, and photos from day parties where everyone wore matching shirts and drank out of watermelons. “He needs this environment,” my father said when I suggested a transfer to somewhere cheaper, somewhere sober. “We don’t give up on family.”

They gave up on me quietly and constantly. When I closed on a creaky craftsman I’d saved for since sophomore year, my housewarming turned into a conversation about co-signing the loan on Marcus’s latest dream—a café with Edison bulbs and no business plan. “Helping family is our duty,” my dad said, beaming as if he’d built the café in his head already. I slid my drink aside and leaned toward Grandma Ruth.

“How do I stop feeling erased?” I asked, voice quieter than the band.

Grandma took my hand. Seventy-eight and still wearing lipstick for war, she had arthritic fingers and bright eyes; she could prune a rose with one hand and rewrite a will with the other. “Your grandfather built this to cradle all his grandchildren,” she said. “Not to be your brother’s ATM. I’ve been watching,” she added, her voice going from mint tea to bourbon. “And I’ve been writing it down.”

Grandma liked evidence. She kept an account ledger in the pantry next to the flour and a binder in the basement next to her canna bulbs. After Grandpa died, she watched my parents treat corporate cards like credit for living—and to understand how they did it, she kept receipts with the same rigor she’d kept recipes. A week after my housewarming, she clomped into the kitchen with a worn three-ring binder and smacked it down on the table like a judge dropping a gavel.

“They’ve been misusing company funds,” she said. “Your inheritance is not a slush fund. Promise me you’ll stand up for it.”

In the binder: screenshots of “office supplies” invoices that matched Marcus’s gym membership payments; travel reimbursements that lined up suspiciously with family vacations we posted on Facebook (“team retreat” labeled under a photo of my mother on a catamaran in Turks and Caicos); and a phantom payroll line for “consulting services,” forty-seven hours billed over three years, $4,000 a month, for work Marcus could not describe to his own reflection.

“Paige,” she said softly, “your heart is strong, but your mind is sharper. Don’t let anyone else write your life for you.”

It wasn’t the first time she’d pushed me. At sixteen, she paid me twenty dollars to balance a checkbook by hand. At twenty-one, she made me sit at the kitchen table with a highlighter and a printout of the company bylaws. At twenty-nine, she handed me my grandfather’s original will, the one that hadn’t been run through my mother’s Shred-It machine labeled “spring cleaning.” The will held a clause I’d never heard: as co-executors of the trust that held the company, my parents owed annual financial reports to every beneficiary. Every grandchild. Me.

They’d skipped my mail three years running.

I’m a corporate attorney. Contracts are my city; compliance is my skyline. I work at Sterling, Matthews & Associates, where my managing partner, Richard Sterling, grew up two blocks over from the house where my father taught me that boys need stability and girls need to practice swallowing. Richard knew my father from Rotary breakfasts where men swallowed rubbery eggs and boasted about philanthropy that could be measured in logos on plaques. Richard had seen the red flags long before I had the courage to ask for help. When I walked into his office with my grandmother’s binder, he pulled a thicker one from a bottom drawer.

“Your parents,” he said without preamble, “have breached their fiduciary duty. Worse, they’ve committed fraud.”

He talked, and the words stacked up in a skyscraper that I realized had been built over the course of years while I’d been busy paying rent on a childhood bedroom.

“Phantom payroll,” he said. “Marcus Harlo, ‘consultant,’ $4,000 a month for forty-seven hours over three years. Mischaracterized expenses: twelve thousand dollars in ‘team building’ that aligns with a family vacation to Maui in January, eight thousand in ‘wellness programs’ that tracked to a gym contract and car payment. Unauthorized loans: two ‘equipment purchases’ for a supposed art studio, funded by the company’s line of credit. And this—” He slid his phone across the table and pressed play.

My mother’s voice, cool and clipped as a February walk, saying, “Paige doesn’t need this money. Marcus needs it more.” In the background, the faint clink of ice in a glass.

“Intent,” Richard said grimly. “It’s not incompetence if you know who you’re starving and who you’re feeding.”

He laid out a plan with the quiet precision of a man who prefers victory to applause. Step one: a formal demand for a complete forensic audit, thirty days to produce all financial records: payroll, credit card statements, reimbursement accounts, vendor contracts. Step two: petition the court to remove my parents as co-executors for breach of fiduciary duty if they refused or produced falsified records. Step three: appoint an independent trustee. Step four: damages. With intent proven, the court could claw back misappropriated funds, and—if the numbers were as bad as Richard expected—award me controlling interest to stabilize the business.

“Are you ready?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, because I could still feel my grandmother’s grip in the bones of my hand.

We sent the demand letter that afternoon: a courier in a navy blazer, a signature at my mother’s office, a whisper inside the walls of a company that smelled like drywall dust and denial.

Three weeks later, my phone buzzed on my grandmother’s kitchen table while she deadheaded orchids and pretended not to check her email every five minutes. A family group text from my mother bloomed on the screen with confetti emojis and sin.

Exciting news! Marcus has accepted the presidency of Harlo Construction! So proud of him for stepping up to lead. Family business stays in the family. Attached: a photo of my brother behind my grandfather’s desk in a suit borrowed and a grin bought. On the credenza behind him, the lease to a downtown office he’d wanted since college, paid for with company funds and a dream of being applauded for holding a pen.

Grandma’s teacup clattered against the saucer. “He’s worked forty-seven hours in three years,” she hissed. “He’s never managed a sandwich.”

That evening, a text from my father: Since Marcus will lead the business, we won’t need your legal advice anymore. Thanks for all your help.

I forwarded the message to Richard with a single line: File everything.

We filed. While the printer in Richard’s office spit out twenty-three pages of formal demand formats and four pages of citations my father would Google, a deputy attorney general in St. Paul read an email from me with attachments labeled: Harlo_Misuse_Summary.pdf; Will_Clause.pdf; Audio_Recording.mp3; Binder_Scans.zip.

In towns like ours, news travels between salad bars and Sunday school. By the time Marcus walked into the country club’s ballroom for Harlo’s annual client appreciation dinner, expecting to be toasted like a man who had built something with a hammer and sweat, rumor had turned the air sticky.

The ballroom smelled like beef and lilies. An ice sculpture of a hard hat sweated on a table near the band. Contractors and councilmen pivoted toward my father’s voice at the bar as he told a story about an out-of-town bid we didn’t need but got anyway because Marcus had the vote. My mother wore a dress the color of melted butter and looked for a camera.

I came in a charcoal suit that made me feel like the first woman in a courtroom and not the only girl at the family table. Richard wore navy and gravity. We came separately. We stood together.

My father took the microphone. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he boomed. “I’m proud to introduce the new president of Harlo Construction, my son, Marcus.”

Polite applause. Someone clapped harder because they were on my father’s payroll.

“Thank you,” Marcus said, resting his hands on my grandfather’s desk in the photo on the screen behind him as if to make it true. “This is a new era. Innovation, growth, community—”

“Marcus,” I said, from the back, my heels clicking a metronome on the marble. “Could you tell the room what qualifies you to lead this company?”

His smile glitched. “I’ve grown up around construction,” he said. “I’ve learned from the best. My parents.”

Richard lifted a remote. The screen shifted to a bar graph labeled Harlo Construction Payments to Marcus Harlo, 2019–2022. The bars stretched high enough to make people sit down.

A murmur like wind through corn. “That can’t be right,” Mrs. Peterson said, standing because she had paid for half the projects in this room with patience and bids.

“I wish it weren’t,” I said into the microphone Richard handed me. “Here’s a scanned invoice for a family vacation listed as ‘team retreat.’ Here’s a gym membership charged as ‘wellness program’ alongside a car payment.”

My father came forward, palms up. “We don’t air family matters—”

“We’re not,” Richard said, turning the page. “We’re airing company matters.” He clicked again. A spectrogram pulsed across the projector; my mother’s voice and my father’s answer drifted over jazz like smoke.

“Paige doesn’t need this money,” my mother said on the recording. “Marcus needs it more.”

The bare truth sat in the room like a stool you stub your toe on.

I put my grandfather’s will up next, the paragraph highlighted where he wrote, in the plain English he used to talk to men on scaffolds: All grandchildren are to share equally in profits and governance of Harlo Construction, with annual financial reports provided to each. Redline: three years of no reports to me.

“I’ve been cut from meetings,” I said. “From profits. From decisions. My honors and hours meant nothing compared to a last name and a smile.”

Mr. Larson, who’d been foreman since my father was a boy who sat in the cab and blew the horn at lunch, thumped his fist on a table. “Paige has been the one reading our contracts for a decade,” he growled. “She saved us on the Maple Street job. What did this boy do besides spin his tires in the parking lot?”

“Paige negotiated fair payment terms,” Ms. Chen, a supplier, called out. “She didn’t take a cent.” She turned to my mother. “You charged us for lunch and called it a ‘vendor summit.’” The room’s polite Ivy folded into itself and went quiet.

Richard nodded. One last slide. The state seal of Minnesota, opaque and absolute: Office of the Attorney General—Investigation Opened.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said in the tone I used when I read a settlement aloud so people would stop bargaining with themselves, “Harlo Construction’s bank accounts are frozen pending inquiry. The court will appoint an independent trustee to oversee operations while the forensic audit completes. Fraud has consequences. So does theft.”

Silence, then noise. The band stopped. Mrs. Peterson’s husband took her elbow and whispered, “I told you.” Jacob from the council moved toward the exit to call the mayor. My mother’s face went a color I’d never seen before. My father sat down, a man learning what the floor felt like. Marcus stared at the projector like it might change the slide if he wanted it badly enough.

Downstairs, deputies in plain suits served subpoenas to a room of board members suddenly alert to the way their wine glass looked in their hand.

I looked toward the back of the room and found Grandma Ruth. She leaned on her cane and smiled at me with a fierceness that made me wish I’d had it in my pocket at sixteen. “You did it, honey,” she said when I reached her. “You shook the rotten fruit from the tree.”

“Only the rotten,” I whispered.

“Leave a few branches,” she advised. “The birds need somewhere to land.”

Part Two

By morning, the lakehouse gate was padlocked, the bank’s maintenance crew gone through the kitchen and left a note on the counter. My parents’ phones pinged with balances down to zero and unread messages that said Call me and We can work something out. The country club called to ask my mother to resign from the charity luncheon committee “to focus on family matters.” The Rotary Club quietly rescinded my father’s membership with a letter about “integrity” typed in a font he’d used to print menus for their pancake breakfast.

Harlo Construction didn’t close. It staggered, grimaced, and walked.

The independent trustee unlocked a file room my mother had declared a “storage closet” and found a second set of books with eraser marks my grandfather would have fired a man over. A forensic audit took three months and a year off my life. It confirmed what Richard suspected and Grandma documented: $318,000 in misappropriated funds, including but not limited to “wellness programs” written in the shape of an SUV, “team retreats” seaside, “consulting fees” for Marcus, and “vendor relations” in restaurants with Zagat ratings.

The court removed my parents as co-executors and appointed a fiduciary to steady the ship. The fiduciary knocked on my door in a coat that still smelled like cold and asked, “Can you come in?” Not because I was family. Because I was competent.

The judge awarded me controlling interest as damages for being deprived of both profits and participation, and because I would not need an explanation for the difference between a ledger and a lifestyle.

My first day back in the office I put on steel-toed boots. I walked the shop floor, shook the hands of men and women who had learned to look past me for my brother, and said, “We’re going to run this like Frank did. Fair wages. Clean books. Safety first. No more vendor lunches unless Mrs. Chen orders and sits at the head of the table.”

We renegotiated contracts my mother had soured with late payments and unapologetic emails. I rehired a project manager my father had “retired” because he wouldn’t look impressed enough at a presentation. I took a county engineer to coffee and asked what we could do to win back the bid for the new elementary school. “Stop billing your family vacation to me,” she said dryly. “And send Paige to the meeting.” “I am Paige,” I said. She laughed, and three months later we were pouring footings for a cafeteria where a generation of kids who didn’t exist yet would spill milk and futures.

I stood up a policy my grandfather would have joked was “just decency.” It was also governance: no company cards for personal use. All expenses documented with receipts that match the thing you bought. Annual financials mailed to every beneficiary with an index you can read. I hung the plaque in the lobby between the photo of Grandpa in suspenders and a glass case with his hard hat in it: Built on Honesty, Proven by Action.

Word got around that the Harlo you wanted to work with was back. Mrs. Peterson returned with a handshake and a hug. City Councilman Williams came by to tell us the school board chose our bid because “we voted for the numbers and the way you told the truth.” Ms. Chen went on a “vendor summit” to our cafeteria breakroom, where we brought donuts and paid the invoice before she got to the parking lot.

Marcus sold the BMW he’d somehow managed to hold onto, and then the car company took it because the numbers didn’t add up to monthly. He packed a garbage bag with t-shirts and left town for an aunt who was always soft on him. My mother shrank by fifteen pounds and stopped wearing pearl studs to the grocery store. My father took up ice fishing and then stopped because silence was not the balm he wanted. They joined a different church further from the lake, the kind that reminds you from the pulpit that shame doesn’t sanctify, repentance does.

They sent letters. “We didn’t realize,” my mother wrote in ink that had always been better at grocery lists than confession. “Family is complicated,” my father wrote. “We thought we were helping Marcus. We know we hurt you.”

I answered each as if my grandmother were counting how many stamps you owe when you send out invitations: one line, two if the day had been good. “I hope you are well,” I wrote. “The audit is attached.” I copied our independent trustee. Over time my messages turned into receipts. Love is not always a casserole. Sometimes it’s a bank statement in clear font that says, You received this much because you are owed it, not because we love you more today.

The most meaningful day wasn’t a victory or a defeat; it was a Tuesday at noon when a young woman named Jenny interrupted me on the shop floor to say, “Should those rebar caps be that loose?” They shouldn’t. She’d been hired out of a vocational program named after a union man I had never met. She saved us a broken ankle and a lawsuit. “Good eye,” I said, and stuck a sticker on her hard hat that said MERIT MATTERS. We both grinned like we’d gotten away with something.

Six months after the court decision, Grandma Ruth’s orchids bloomed three flowers in a week. She called me to come see and then called me back to bring her the green cardigan. In the hospital her hair looked belligerently like itself. “You saved this company,” she said, voice weak and strong at once. “Your grandfather would be so proud.” She squeezed my hand and then let go.

We buried her in a coat that still smelled faintly of Chanel and peat. The county engineer came. Ms. Chen came and put a lily on the casket because lilies are what you bring when the dead liked lilies. Mrs. Peterson’s husband whispered, “That woman could make a banker cry,” like a eulogy. In the lobby, next to the photo of Grandpa, I put a small framed snapshot of Grandma at the kitchen table with the binder between us, both of us grinning like we had gotten away with something. Below it, a card in her handwriting: Don’t let anybody write your life for you.

People in town like to say I destroyed my parents. I didn’t. They did that years before the bar graph went up on the projector. I just plugged the cord in and turned on the lights.

At Christmas my parents sent a card with a dove and the word Peace in gold. Sarah sent a photo of a baby—her son, my nephew—chewing on a plastic key ring. “I hope someday you’ll meet him,” she wrote. I put the photo on my refrigerator because you can be strict with the adults and soft toward the children who didn’t choose any of this. I wrote back and said I hoped so, too. Then I added, “When you’re ready to talk about how we got here,” and underlined we because forgiveness isn’t charity; it’s a contract you both sign.

Harlo Construction’s balance sheet zeroed out ugliness faster than my heart did, but both trended toward black. On the first anniversary of the dinner that turned into a verdict, we threw our client appreciation in the field behind the office instead of the country club. No band. No ice sculpture. Food trucks and a dunk tank my foreman kept missing on purpose and Mrs. Peterson kept hitting on purpose. We raffled off an apprenticeship and three scholarships to the tech college for kids who didn’t have a last name the Personnel Department recognized. Marcus’s name did not come up, even in whispers. My parents didn’t come. Ms. Chen ate a brat and said, “This tastes like honesty,” which is the best review a brat can get.

On a rainy Monday, Richard Sterling popped his head into my office and tossed a file on my desk. “You owe me a coffee,” he said.

“I owe you half a company,” I said.

He shrugged. “You did the work.”

After he left, I read the file: final report from the independent trustee closing the books on the audit, a lodestar that read, Operations stable, governance restored, misappropriations repaid. I put it in a drawer with a lock. Somewhere in town, my mother was clipping coupons. Somewhere else, my father was counting his decoys. Somewhere else still, Marcus was learning how to refill a café’s salt shaker with a kind of humility that does not trend on Instagram.

In the lobby, I replaced the lilies on the memorial table with fresh ones and straightened the plaque beneath my grandfather’s hard hat. A young man in a paint-splattered sweatshirt stopped and read the inscription.

“Was he your dad?” the kid asked.

“My grandfather,” I said.

“He looks like he could yell and hug at the same time,” he observed.

“He could,” I said. “So can a company.”

On my way to a meeting with the city engineer, my phone buzzed with a text from my mother. We’d like you to come by for dinner. Just us. No expectations. I stared at it too long. Richard would have told me to let it sit. Grandma would have told me to eat first. I screenshotted the message and sent it to my therapist and to Pamela—my girlfriend of six months who had arrived with her own toolbox and a patience that made me suspicious at first.

“It’s okay to say no,” Pamela texted back. “It’s okay to say yes with an agenda. It’s okay to say, ‘Only if we sign a napkin first.’”

I thought of a twelve-year-old boy who blew a horn at lunch and a sixteen-year-old girl who soldered a lamp and a seventy-eight-year-old woman who underlined clauses in wills like other people underlined scripture. I typed a reply: I’ll come. I’m bringing the audit. And a casserole.

“More casserole, less audit,” Pamela texted. “You’re not billing them.”

She was right. I wasn’t. I was billing the past.

That night at my parents’ kitchen table we ate a chicken casserole so bland it could not offend anyone and said sentences we had not learned in church. My father said, “I am sorry,” like a man putting his initials into wet sidewalk and hoping it sets. My mother said, “I thought love was making sure Marcus never missed,” and I said, “I thought love was making sure I never asked,” and we moved on. Not forgiven. Not yet. But moving.

As I left, I paused by the refrigerator. The baby photo Sarah had sent was held up by a magnet shaped like a hard hat from a contractor conference fifteen years ago. My mother saw me looking. “Sarah’s coming by next week,” she said. She meant, You should meet him. I meant to say yes then. Instead I said, “Let me send you the scholarship application for the tech college. For anyone’s kid.”

In the parking lot, it had started to snow, soft flakes determined to clean what they could before the next muddy thaw. I stood there and breathed in the cold until it hurt. When I reached my truck, my phone buzzed. A message from the city engineer: Meeting pushed. But also—we’re naming the new gym after your grandfather. Board vote unanimous.

I laughed into the snow and thought of Grandma’s binder. She would have said, “About damn time.”

People like to say the best revenge is living well. I think that undersells it. The best revenge is governance. It’s receipts with explanations; it’s bank statements that align with the thing you bought; it’s answering a Friday call from Ms. Chen with a Monday morning check. It’s hangers labeled, keys hung, napkins signed, clauses honored, nephews met when it’s time. It’s remembering that family is a noun you earn with verbs: show up, pay back, make right, build on, tell the truth.

The lake holds a car every few winters. Everyone cautions everyone else. And someone always tries it anyway. This year, when the ice groaned under a pickup on New Year’s Day, the driver stopped, opened his door, and walked back to shore. He left the truck to sink and live on as a story.

People asked me later if I wished my family had sunk. No. I wished my grandparents had lived to see what we built on the ice after we finally listened for the groan.

In the lobby, under Grandpa’s hard hat, the plaque still reads Built on Honesty, Proven by Action. Every Monday, I put fresh lilies in a vase next to it. Every Friday, I walk the shop floor and ask Jenny and the crew what we missed this week. Every night, I drive past the lakehouse that is no longer ours and think of how thin ice looks like truth when you want it to be. Then I drive home to a kitchen that’s full of casserole and contracts and a woman who says, “You didn’t save them. You saved you.”

And when my brother calls from a city two states away to say, “I got a job offer,” I say, “You did that,” and mean it.

They wanted me to return when the money ran out. I came back when the math added up.

Justice didn’t need fireworks. It needed a ledger. It needed a binder. It needed a granddaughter with a good lawyer and a grandmother with orchids and a town that still believes in bridges.

It needed me.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My daughter-in-law slapped me in the face and demanded my house keys! CH2

My Daughter-in-Law Slapped Me in the Face and Demanded My House Keys! Part One The slap landed before I…

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing. CH2

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing …

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down The Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything. CH2

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything Part One My…

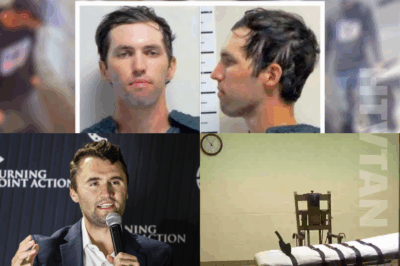

Suspect In Charlie Kirk Killing Could Face The DEATH PENALTY — Utah Signals An AGGRAVATED Murder Case

Prosecutors booked 22-year-old Tyler Robinson on aggravated murder, a charge that opens the door to capital punishment under state law….

“We will find you, we will try you and we will hold you accountable to the furthest extent of the law. And I just want to remind people we still have the death penalty here in the state of Utah.”

Utah Governor Spencer Cox Issues STARK WARNING — State STILL Has The DEATH PENALTY As The Charlie Kirk Case IntensifiesHours…

SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME “YOUR CHILDREN ARE MINE.”

“SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE” MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME—‘YOUR…

End of content

No more pages to load