My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She saw the bruises, looked at me, and said, “you’re safe now.” Then she picked up the phone…

Part One

He hit me so hard I heard the crack before the room went black with pain. It was the kind of sound that lives on in your bones, a dry, decisive punctuation that leaves no room for arguing it away. I tasted copper. My breath came jagged and shallow. For a second the world was only color and the feel of carpet against my cheek, and then — as if from a very long distance — my mother’s voice slid across the apartment like ice.

“Stay quiet,” she whispered, quite close, as if the two syllables were a recipe. “He has a future.”

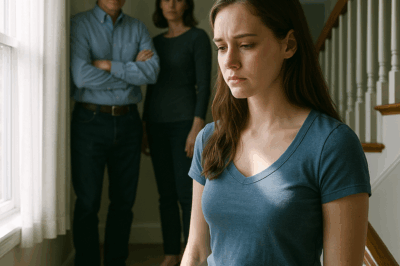

Those were the words that shaped the rest of my life for a while: not the slap, not even the bone, but the instruction to be small, to render my pain invisible so his prospects would remain shiny. He was my brother, older by two years, once my protector and companion and now my judge. When he smiled in public, people said the word proud; when he clenched his jaw behind closed doors, that same pride turned predatory.

I grew up thinking the arc of family was predictable. Brothers rescued sisters from bullies, mothers tucked hair behind ears, fathers checked backpacks and fixed shelves. Small harms were soothed with bandages and marmalade and the promise that tomorrow would be better. But sometimes the promise was a contract written to favor one signature over another. In our house, my brother’s future had always been the important thing — scholarships, internships, good clothes, the quiet admiration of neighbors. He had been the golden child long before he learned how to hit.

The abusive episodes began small: a shove that could be explained as “you tripped,” a hand that lingered too long on my arm and left the shadow of a bruise the next day. He called it tough love. Mom excused it as stress. I memorized excuses the way other children learn nursery rhymes. Each time I believed the apology, and each time the apologies grew thinner and the bruise thicker.

The last time, he broke my ribs.

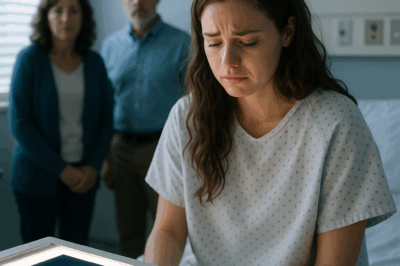

I went to the emergency clinic because I could not catch my breath. The intake nurse’s careful, professional way of asking about the injury felt like a shoreline, testing whether I would wade into telling. I tried to keep my answers short. I said I’d fallen. I said I’d slipped against a piece of furniture. I practiced the little deceptions that would keep headlines and neighbors and pity out of my life.

Then Dr. Patel pushed my sleeve back and saw the purple crescents, the patterns on my torso like a map someone else had drawn. She pressed gently where the pain flared and did not flinch away. Her eyes met mine, steady and unsurprised in a way that made me feel less ridiculous for sitting there with a broken body and a house full of silence.

“You’re safe here,” she said, quietly.

There it was: not “I hope” or “I wish,” but a statement. She picked up the phone and asked to speak with social services and the police. She asked me if I wanted to press charges and whether I had a safe place to go. I felt something small loosen — not the pain, not even the fear, but a knot of the older, animal panic: the sense that this is all my fault and if I only stayed small enough it would all stop.

Mom called three times while I was still in triage. I declined. My hand shook so much I had to hold the phone with both of them and tap the decline button with the corner of my thumb. She texted later: “He didn’t mean it. You have to be strong. He has so much going for him.” The words made my stomach sink. A life described as “so much going for him” had apparently taken priority over the shrieking in my chest and ribs.

Despite the whispers and a history of being kept small, I said yes to Dr. Patel that day. I let her call the police. Let her take the photographs, file the reports, arrange for a safebed in a women’s shelter while they tried to verify that the house would be unsafe if I returned. There were social workers with kind, efficient faces who explained the legal steps and the emergency orders and the help available. It felt like being offered a lifeline — like someone had thrown down a rope and said, climb.

When the officers arrived at our apartment and knocked on the door, my brother laughed in that infuriating way he did when he thought something was a joke. He opened the door in his socks, not looking like a man who had just snapped and broken someone’s ribs. He was surprised to see uniforms.

“She’s lying,” he scoffed. “You know her — dramatic. This is ridiculous.”

But the police had what they needed: a medical report, photos of the bruising, a statement from the ER nurse. They had a neighbor who’d heard screaming the night before and a landlord who had seen a crack on the wall when the furniture had been thrown. The weight was not mine to carry anymore. The world had people and processes that, sometimes, actually functioned.

There are worse betrayals than violence. There are quiet renunciations — the moment a parent looks you in the eye and calculates that your sister’s life is cheaper than their son’s future. My mother stood there when the police read the temporary restraining order and when they put handcuffs on him, and she looked at the ground, like a person who had been baptized in shame and had not yet learned how to swim.

When my brother was led out, packet of personal items in a plastic bag, he shouted one thing as the patrol car door closed: “Tell her I love her! Tell her I didn’t mean it!” My mother’s face did not move. For the first time in my life I didn’t feel small because someone had said it; I felt full-sized because the thing I had been told to protect — his future — was now being called into question by his own actions.

That night I slept under the fluorescent hum of a room in the shelter and understood the meaning of being seen by strangers. They did not call me “drama” or chide me for ignoring “family.” Instead, they said the words people habitually forget to speak: “You did the right thing. You’re safe now.” Honestly, it was a kind of miracle.

Part Two

The police filed a case. The prosecutor’s office assigned a victim advocate. There were days that bled into one another: forensic interviews, court dates, social worker meetings, and therapy sessions. The legal process is slow in a way that’s both infuriating and cleansing. It requires you to revisit your wounds with a clinical steadiness that makes emotion a liability you must set aside. I learned to tell the truth like an accountant balancing numbers: concise, unquestionable, and factual.

My mother came to court the first time. She sat with her hands folded in her lap, fingers plaited tight, as if knitting her guilt into a rope. She looked at me intermittently — not with the tenderness I had once searched for, but with a combination of confusion and worry, as if she had been injured in the same way I had and needed reassurance for her own choices.

On the witness stand I had to describe things that felt private and shameful in their intimacy: how he’d cornered me in the kitchen that January night when he’d been angry about dinner, how he’d pushed when the words spiraled too close to truth, how the force landed along the right side of my torso and the world simplified to pain. I recited the facts; the prosecutor’s face was a map of concentration. The defense tried to paint me as hysterical, as someone with a motive rooted in family drama. It is a grim irony that telling the truth can sometimes feel like painting your life in a color someone else calls false.

After a week in custody and several hearings, my brother was arraigned and charged with aggravated assault. He posted bail and was allowed home under strict conditions. That decision made my mother furious — at the system, at me, and at the way a man she had raised could be hauled into a courthouse like a common criminal. I do not pretend the law was perfect in its measures. It is not. But it was a start.

Rebuilding the house of our lives required more than court orders. The prosecutor recommended family counseling, and the judge ordered probation with mandatory anger management and a strict no-contact order. For my brother, the order felt like an affront; for me, it felt like the space oxygenated.

My mother was quieter now, forced into a reckoning she had refused for years. She visited me once in the shelter and brought clamshells of takeout we ate with plastic forks, both of us perched on metal chairs like refugees of the same war. Her hands shook as she reached for the styrofoam, and she said — finally, without calculation — “I’m sorry.”

“You kept saying his future,” I said. The words were not a question. They were an accusation and a test.

She looked at me like a woman who’d been asked to read a letter she had written in another life. “I thought I was saving him,” she said. “I thought if he failed it would take everything. I didn’t want to go through what my mother did — the shame. I was terrified.”

I understood the trajectory; I understood how fear, when it finds a family, makes itself at home. Fear says, hide the problem; fear will say, choose the easy remedy; fear will say, sacrifice a child so another can flourish. But understanding did not mean consent. She had made choices that did not belong to her alone.

There were days when I wanted nothing to do with her. Anger felled me at odd hours, sudden and deep, the kind of rage that makes you want to throw a chair and then collapse in exhaustion. There were nights when I would put a palm to my side and imagine the healed scar. It is one of the weird truths of survival: wounds can teach you who you can be, and sometimes that version is sharper and more dangerous than the one that existed before the violence.

At some point during the legal process, my brother’s charming public persona cracked. Family friends who had once lined up to praise his projects and internships now kept their distance, offering condolences to my mother in the quietest, least committal ways. In private, conversations bubbled about responsibility and the cost of ignoring warning signs. For my brother, the consequences were material: his scholarship was put on probation; the internship that had been the sun around which he orbited evaporated in the face of background checks. He found himself reduced to someone who had to explain himself to strangers who were not inclined to be lenient.

This part of the story is not catharsis — it’s administration. It is the slow, sober accounting of debts paid and obligations met. The real work was not in punitive measures but in the daily acts of remade life. I worked with a therapist who taught me the small architecture of safety: locks that were different from fear, boundaries as walls that kept the cat from the stove, not punishment. I learned how to call a friend and say, “I am here; can you come for twenty minutes?” and not feel ashamed. I learned what it meant to sleep without listening for footsteps downstairs.

Months passed. My brother complied outwardly with some of the court-ordered mandates. He attended the anger management classes because the law required it, not because he wanted to transform. He completed community service reluctantly. One morning, I heard he had been arrested for violating the no-contact order — a callous text sent in the night that thought itself anonymous. The judge had a short temper for repeat offenses. The sentence was not long, but it was real: a string of nights in county lockup and a misdemeanor added to his record.

When he served that time, his mother wept in the empty apartment at night. She came to my place once, unexpectedly, after his stint in jail, and she brought a small, shaky apology. “I made a terrible mistake,” she said. “I’m trying to be better.” She sounded like a tired student learning a language she had once declared she already spoke. It took a very long time for me to accept even the imperfect shape of that apology.

There is an odd economy to forgiveness. It need not be absolute. It can be contingent, a slow contract of earned trust. I heard her say sorry and then asked her to come to counseling with me. I asked her to listen to the things I had heard and witnessed without trying to explain them away. She did, haltingly. We sat in rooms with therapists and read lists of behaviors and asked how to repair trust when it had been used as currency.

Legal consequences changed how our family behaved in public. They did not make my brother into a virtuous man. But the legal box — the court’s orders, the fines, the probation — created practical boundaries that made it harder for him to repeat the violence without consequence. Social ostracism did its part as well; the people who had once admired his charm withdrew that admiration and watched instead with a wary, watchful gaze.

For me, healing came from the small victories: a morning when I lifted a grocery bag without wincing; a night when I walked from a bus stop in the rain because I wanted to and not because I feared the walk. I found work that valued steadiness over bravado and friends who celebrated small competent acts. I learned what it meant to be trusted again, and that learning came with patience.

My mother and I did not stitch our relationship like a single seam. We installed a garden path of small repairs: we met for coffee and traded thirty-minute conversations about mundane things, like who to call about a leaky faucet or what the bakery on the corner had on sale. We argued about politics like people who knew each other’s contours. One evening, she brought a pot of soup and a letter. The letter was addressed to me and written with the tremor of someone who wants redemption but doesn’t know how to buy it. She had written down the moments she could no longer excuse, naming them like crimes, and then she wrote what she would do differently. It was a small, imperfect document. It was progress.

My brother served his probation and eventually found work that did not come with a fancy title. He was quieter, thinner. Regret does strange things to a person; for him it bent him inward, like a limb gone dull with overuse. He called once in the night months after everything, voice small and shaky, asking if I would ever consider speaking to him again. I told him the truth: not now, maybe never in the way things had been, but I wanted him to be safe and to be responsible. He cried. That was not triumph for me; it was only an acknowledgement that he, too, would have to live with the consequences.

There is a scene I will not forget. Two years after the arrest, my mother and I walked through a civic center where they had hosted a talk on domestic violence awareness. The room was full of people who had been hurt and people who had learned how to help. My mother sat at the edge of the room and watched the speaker with a tenacity I had not seen in her before. When the talk ended, she turned to me with wet eyes and said, “I have been wrong.”

These were not words that erased the past. They were a small, solemn building block. We left the event and stopped at a coffee shop where she bought me the wrong pastry and then insisted on paying anyway. Small things — a pastry purchased, a call returned — do not make a whole life, but they make a beginning.

In the end the criminal justice system did what it could: it documented, it punished within its limits, it provided structure. But the true work of safety was social and domestic: creating day-to-day routines that had teeth. Locks were changed, neighbors were informed, and my mother and I learned to be honest without dramatics. I resumed work and eventually moved into a small apartment that smelled of lemon and had a balcony with a single plant I remembered to water most days. I kept the scar on my ribs as a private testament, not as a trophy.

Sometimes people ask me if I hate my brother. The right answer is complicated. There is anger, yes, and the particular grief of a lost sibling. There is disappointment in the person he refused to become. And there is a heavy compassion for the fact that every human hatched from a childhood; we all carry flawed tools. I am not a saint. I am not a person who forgives without boundaries. I no longer offer him access to my life in the old ways. I do not answer his calls in the middle of the night. I would help him in a crisis if it did not put me in harm’s way.

The very last strand is a humble one: justice and life are not the same things, and any story that ends with neat closure would be lying. The ending I have is simpler and truer: I am safe. My bones have mended. My mother learned, painfully, the cost of choosing a child over a child. My brother received consequences he could not chalk off as a minor lesson. Our family is altered permanently, and in that alteration there is an honest account of what happens when someone decides that a future is more important than a life.

On an ordinary Tuesday I stood in my kitchen and made tea. The kettle sang. I thought of the doctor who did not blink when she saw me, and I felt gratitude so big it was almost physical. She had stepped outside her clinic and into my life with a phone call that bounced legal systems and social services into motion. Her quiet confidence had been the hinge on which everything turned.

I called her one afternoon to tell her I had started volunteering with the shelter that had taken me in those first uncertain nights. She laughed softly and said, “Good. People who have been alone know how to keep company. They’re the best kind of allies.”

That is the final truth: the person who picked up the phone that day did not make me brave. She offered a path. The bravery came from a slow accumulation of small acts: speaking the truth, keeping records, showing up to court, learning to sleep again, and refusing to let someone else assign my worth.

My scars are a ledger of survival. My mother’s apology was a contract she keeps up with tiny, daily acts. My brother pays into the system of consequences. I keep my life small in some ways and wide in others. I know how to call for help now. I know the names and numbers of people whose voices will come when I need them. I keep a new type of future — one where my ribs might ache on cold mornings but where the air comes easier and the word “safe” is no longer a rumor whispered into the dark.

The last line is not triumphal. It is practical and true: the moment my doctor picked up the phone and spoke, my life split into before and after. The after is not perfect, but it is mine. I still have mornings when my ribs remember the crack like a bad dream; those mornings, I breathe and count the small mercies: a therapist who returns my messages, a neighbor who waters my plant when I am away, friends who have made my kitchen a place of laughter again.

And when I fold the laundry now, I do it quietly, with a kind of blessing that used to be reserved for weddings: may this garment be warm and may the body inside it be safe. The rest is life’s careful, unglamorous ongoing work — the work of living after betrayal and choosing, again and again, to be whole.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing. CH2

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing Part One Stop. Stop, stop—you’re…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER-IN-LAW ASSAULTED ΜΕ- BLOODY FACE, DISLOCATED SHOULDER MY SISTER JUST SAID”YOU SHOULD… CH2

My brother-in-law assaulted me — bloody face, dislocated shoulder; my sister just said “You should’ve signed the mortgage.” All because…

End of content

No more pages to load