My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal

Part One

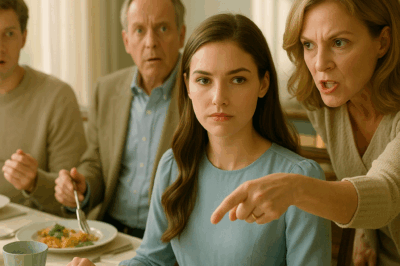

The room was a cathedral of polished money—crystal stemware, velvet drapes, a Monet I knew had never been cataloged on any public loan. William Harrington thrived in rooms like this. He cultivated them the way a vintner nurses vines: pruning dissent, bottling power. He raised his glass, the lighting catching on diamond cufflinks, and didn’t bother to disguise the contempt weighing down his mouth.

“My son deserves better than someone from the gutter,” he announced to three dozen guests and a string quartet playing Schubert like they meant it. “Street garbage in a borrowed dress, pretending to belong in our world.”

It wasn’t the first time a rich man had decided to narrate me to a crowd. It was the first time he did it while I sat across from him wearing a dress I designed as a hedge—silk that could move with me whether I chose to stand or stay, fabric that loved a quick exit.

I folded my napkin, set it down beside an untouched slice of salmon, and stood. Somewhere along the table, Quinn’s mother, Rachel, breathed my name like a warning. Next to her, Patricia—the sister whose smile always reached the press releases—hovered on the edge of glee and pity, both of which needed an audience more than a reason.

“Thank you for dinner, Mr. Harrington,” I said. “And thank you for finally saying out loud what you’ve always thought.”

“Zafira,” Quinn said, reaching for me under the table. I squeezed his fingers once and let go. He had the same hands his father did; only his shook when he was angry.

“It’s fine, love,” I murmured, not taking my eyes off William. “Your father’s right. I should know my place.”

He smirked. One of the country club men chuckled. Somewhere in the orchestra, a violinist glanced up, bow pausing midair. I walked—past the painting his foundation bolstered with tax credits, past the statues he thought proved taste, past the Bentley he had mentioned cost more than I would “make in five years,” past a valet who apologized with his eyes.

My car was the tidy kind of sensible. The kind the internet liked to point at as proof a woman only valued money if she spent it loudly. When the door closed, I let the first tremor out of my hands and dialed.

“Danielle,” I said when my assistant picked up. “I know it’s late.”

Her voice softened into familiarity reserved for the versions of me only she saw. “Talk to me, boss.”

“Cancel the Harrington merger.”

A beat of silence that was really a pivot on high heels. “Our two-billion-dollar Harrington merger?”

“That’s the one.”

“Due diligence is complete. Financing is in place. The board is—”

“He called me garbage, Dani. In front of his board, his bankers, his friends. He made it clear a woman like me will never be good enough for his family or his business. Kill it.”

I could hear her fingers rearranging the evening on her keyboard. “On what grounds?”

“Irreconcilable differences in culture and vision.”

“You want me to prep a leak?”

“Let him wake up to the notice first,” I said, my jaw already unclenching at the thought. “We’ll let the media have it by noon.”

“With pleasure.” The clickety cadence slowed. “Anything else?”

“Yes. Call Fairchild. Offer them breakfast Monday, my office. If Harrington won’t sell, their largest competitor might.”

She exhaled, and I could hear the smile. “Garbage takes itself out.”

By the time I reached the city, my phone had the look of a wildfire—thirty-plus missed calls. Six were William. It must have tasted like ash to him, dialing a number he would never admit he wanted. I ignored them all, poured myself two fingers of scotch, and watched the city blink. People always say you can see success from a penthouse. Mostly you see repetition—windows flickering, lives looping. I slept as if I had anchored something heavy in the river and let the current carry it away.

By morning, Danielle had done what Danielle does—handed a smoking crater to the other side and a sanitized sentence to the press.

“Bloomberg wants a quote,” she said when I picked up. “I told them Cross Technologies is exploring opportunities better aligned with our values and vision.”

“Vague and devastating. Good.”

“The other thing,” she added, dryness returning. “William Harrington is in our lobby.”

I stared at the phone, then at my coffee, then at the city. “Security letting him up?”

“Not without your say-so. He’s staging a small Greek tragedy down there. I can have him removed.”

“Send him up,” I said. “Have him wait in C.”

“C is the one with the chairs no human spine can love,” she said brightly. “I’ll make him a nice, long pot of room-temperature silence.”

Forty-five minutes later, I walked into Conference C to find the patriarch smaller than his rimless glasses. His hair had lost a war with the morning. His jaw was set in a way that told me he thought clenching was a form of strategy.

“Ms. Cross,” he said, standing because his body knew a habit his ego did not. “Thank you for seeing me.”

“You have five minutes.”

“I’m sorry about last night,” he said, words moving past barbs. “My words were—”

“Inappropriate?” I tilted my head, then laughed, not cruelly, just accurately. “You called me garbage at your table.”

“I was drunk.”

“No.” I stepped to the window where the city sprawled like a circuit board. “You were honest. Drunk words, sober thoughts.”

He straightened, disdain polishing the rim of his voice. “What do you want? An apology? Take it. A statement? I’ll have PR—”

“Why would I do business with a man who thinks I’m beneath him?” I asked without turning. “Tell me that. Convince me the same board who watched you humiliate me would vote yes to my values.”

“It’s not personal. It’s business.”

“Everything is personal when you make it personal, William.”

He didn’t like the first-name. Men like him never do. I turned then, the city throwing light onto the table between us. He had done his homework on the version of me he wanted to see: foster homes, free lunch, graveyard shifts that bought textbooks. He had not traced the other lines.

“You dug where everyone digs,” I said. “You saw where I started and stopped there. You never asked where I was going.”

He eliminated compassion from his face like a thing you could sand. “Cross Technologies succeeds because you got lucky with product,” he said.

“Cross succeeds because I remember being hungry,” I said evenly. “Because I remember what it feels like for a door to be a judge. Every hire, every deal, every line of code—we ask if we’re creating opportunity or protecting privilege.”

“You’re making me responsible for a social agenda.”

“I’m making you responsible for your culture. Name one person on your board who didn’t attend an Ivy League school. One executive who grew up under the poverty line. One senior manager who worked three jobs to finish community college.”

His mouth stayed shut. Silence, properly used, is a fact.

“The merger is dead,” I said. “Not because you insulted me, though that did the math for me faster. Because you showed me who your house is for.”

“This will ruin us,” he said quietly. “Without this deal, Harrington won’t survive two years.”

“Then maybe it shouldn’t.” I moved to the door.

“What about Quinn?” he snapped, finally, his voice finding a human. “You would destroy his inheritance.”

I paused, hand on the steel. “Quinn is brilliant,” I said, turning just enough to let my eyes hold his. “He doesn’t need a hand-me-down throne. He can build his own.”

He flinched, the first crack of something like grief.

“Can you say the same for yourself?” I asked.

Back upstairs, in my office built to look more like a lab than a throne room, Danielle handed me messages and a raised eyebrow that deserved a better backstory than “He deserved it.” Before I could deliver one, she added, “Fairchild is thrilled about breakfast.”

“And?”

“Quinn is waiting in your office.”

He looked smaller in my chair, knees pulled up, coffee cooling at his elbow. When he saw me he stood too fast, and the mug slid, and we both reached to catch it, and hallelujah for lids.

“I watched,” he said, voice rough from the scrape. “The feed.”

I leaned on the desk the way you do when the ground beneath you is both a cliff and a launching pad. “He shouldn’t have—”

“No,” he said, stepping into the sentence, the space, me. “I should have stopped him. I spent a year apologizing for him without making him stop. That’s a cowardice, and it’s a luxury, and I’m finished with both.”

“What are you saying?”

“That I want to build something that would embarrass him for all the right reasons,” he said, and it was the first time I’d seen his father’s jaw used for purpose instead of posture. “Without his money. Without his Rolodex. With you if you’ll have me.”

“Walking away will cost you,” I said. “Rage. Headlines. The kind of family that looks at love like it’s a shareholder vote.”

He smiled then, and I remembered his laugh even before I heard it. “Zafira Cross,” he said, glancing at the laptop open to the termination notice I hadn’t closed. “You just made a choice that cost two billion dollars because I was loved by a man who doesn’t know what love is. I think we can afford what comes next.”

My phone buzzed like a hornet. Danielle. “William convened an emergency board meeting,” she reported. “Our source says there’s talk of going over his head.”

I put her on speaker. “Tell them Cross would consider a future with Harrington under new leadership.” I let each syllable sit in the air between Quinn and me like a chalk line. “Emphasis on new.”

He swallowed. “You’re going to oust my father from his own company.”

“I’m going to give them math,” I said. “Evolve or perish.”

“He won’t go quietly.”

“I wouldn’t expect him to.”

“My mother will cry.”

“Definitely.”

“My sister will write another song.”

“We’ll survive Spotify.”

He let out a breath that tasted like relief and fear. Both are nutrients when you’re building something that matters.

That afternoon, my phone turned into a parliament—the kind where everyone calls you when the only thing left to discuss is the inevitable. Harrington’s general counsel wanted a call; I offered a calendar. Martin, the CFO with numbers for bones, texted me a string of ellipses followed by thank you. An anonymous board member sent a single line: About time. William didn’t call again. Pride is a brand; men like him wear it until their skin bleeds.

The board moved fast, which is to say they noticed gravity. An hour before sun-down, a press release announced William’s retirement “to focus on his family.” I smiled at the phrasing and sent a text to Danielle that said we should send them a fruit basket shaped like a guillotine. She replied with a gif of Rihanna clapping.

By Tuesday, Cross Technologies announced ours: a merger with a newly structured Harrington Industries that would do the hard things—the inclusion audit, the board seat shuffle, the policy rewrite that turns diversity from a slide into a spine. On Wednesday, I stood in front of our people and said the sentence I had been building my whole life toward: “You don’t need a gate to make something worth guarding.”

On Thursday, Quinn signed a contract that made him head of strategic development. He had eyed the title like it was trying too hard. I told him titles were bait for other people to underestimate you with. He kissed me in the elevator and whispered, “Then let them think I am merely strategic.”

The rest of the week, the internet decided things about us—queen, savage, villain, girlboss, daddy issues, tastemaker, harpy, icon. I learned long ago not to build my interior around words I didn’t choose. In all the noise, one voice cut clean: an email from a girl in Milwaukee who wrote, My stepfather calls my mother worthless. She thinks her value is a sale at the grocery store. When you said “maybe it shouldn’t survive,” I remembered we are allowed to say that about more than companies.

I took a breath that made room in my chest where something heavy had been.

By the weekend, William’s face on cable business shows said all the things fall taught you when you were a child—pride is brittle, gravity has opinions, and you can break your own neck staring up at a throne. Rachel called Quinn and cried, and he said he would see her, and I kissed his temple when he hung up because compassion is also an inheritance, and he should keep the parts worth keeping.

We drove out of the city to a place with trees that were older than our grandfathers’ bank accounts. We didn’t talk about work. We did talk about the kind of kitchen we might build together—not white marble and knives you’re afraid of, but a stove that forgives mistakes and a table that welcomes elbows and a drawer that will always, always have a lighter in it for candles on a Tuesday.

“Do you ever get tired?” he asked, looking up through branches like scaffolding.

“Of power games?” I said. “Exercise doesn’t tire your soul. It ruins your shoes.”

He laughed. “That’s a yes.”

“I get tired of needing to be louder than a man who thinks volume is argument,” I admitted. “But I have a good team. And we own the microphone now.”

We lay on the forest floor and let the leaves cradle our skulls the way they do when they think of us as mulch and they’re not wrong. Somewhere above us, a hawk wrote a sentence in the sky and didn’t need anyone’s permission.

Back in the city that night, I wrote William a letter I would never send:

You should have learned this as a boy—do not spit on the shoes that later might carry you across your own finishing line.

I slept without dreaming for the first time in months.

Part Two

The first Harrington board meeting without William felt like sinking into a chair that used to be a throne and discovering it was just furniture. The new interim chair—a woman named Mei Lin who had built a battery company from a garage into a continent—ran the room like a conductor: firm wrists, warm eyes, no tolerance for out-of-tune egos. She opened with a sentence that made me love her immediately.

“We will not fix culture by memo,” she said, tapping her pen against the wood. “We will fix it by behavior.”

We talked policy. Not the palatable kind—real surgery. A binding succession framework that didn’t begin with a family tree. A board refresh that retired three men whose only recent contribution had been golf. A scholarship pipeline that would bring interns into engineering from the exact places William believed were beneath him. A supplier audit to make sure the hands that assembled our hardware weren’t digging their own graves for pennies. It sounded like work because it was.

A week into the merger, an envelope arrived addressed in a hand I recognized. Patricia’s handwriting had always been a font and a warning: a performative loop at the P that told you how she did her hair. The card inside looked expensive; guilt likes to dress up.

Zafira, it read. You made your point. Father has been punished enough. You cannot punish Mother for his sins. Return the wedding invitation I sent. Or else, do not bother ever calling me again.

I turned it over, looked at the weight of it, then slid it into a drawer with a small assortment of relics I keep for days when I forget I am right: the nametag from the warehouse night shift where I learned comfort is not a given; the first patent notification Cross ever filed; a note from a teacher who once told me my brain was a cathedral even when my grades were a coupon book.

“Do you want me to call her,” Quinn asked that night, “or do you want to answer in the language she understands—publicly?”

“Neither,” I said. “You go to your mother with flowers. I will buy more folding chairs.”

He came back from Rachel’s with tears and the resolve to accept her love on new terms. “She says she always knew he was a storm,” he said. “She apologized for making me think I had to be lightning.”

We built a kitchen. Not the metaphorical one—the one in the place we rented before we could justify buying the one with the view that insulted the sky. It had slate countertops that hid knife scars. The stove had eighteen thousand BTUs and a temper. We stocked the pantry the way my childhood brain dreamed of: jars of beans like planets, a spice shelf that could tell you a story about every woman who taught me how to cook without throwing away her language to do it. Quinn learned to chop an onion without crying; I taught him it was okay if he did.

In business, the work that makes headlines is never as hard as the work that makes a difference. The day we struck our first university scholarship partnership with a community college two bus lines from where I used to eat breakfast standing up, no one noticed. When one of those students deployed her code to patch a security hole that could have cost us millions, no one wrote a profile. When we built a childcare stipend into the job offer for a woman who was going to turn our battery efficiency inside out, three men on the board called it “interesting” like they were tasting hummus for the first time. We did it anyway.

There were attempts at sabotage—the old guard rarely leaves without trying to salt the earth. An anonymous op-ed in a finance blog called me a demagogue; a senator’s nephew tweeted a thread linking me to my foster mother’s neighborhood like poverty was a plot. A hedge fund tried to short our stock on a rumor that smelled like cigars. You can tell the difference between a good-faith critique and a tantrum by the way it hits your skin. We fought the tantrums with facts and lawyers. We listened to the critiques that came from the very people we said we wanted to serve. We changed decisions that deserved to be changed.

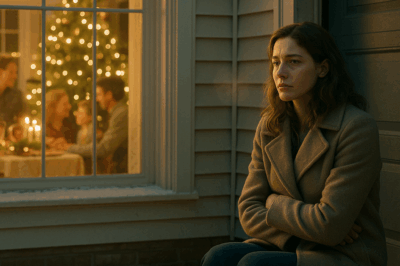

William’s silence became a character in our lives. It moved through holidays like a draft. Rachel invented recipes that didn’t taste like absence and brought them to our table anyway. When we mailed wedding invitations, I addressed one to “William Harrington” and put it in the box because grace is free to give and useless if you count it. I did not expect him to come. He did not.

On a Tuesday afternoon in March—gray light, road salt staining the curbs—I left the office early. I turned off Sharpe ratios and vendor pricing and sat in the quiet of our living room and read a book that had been following me around with sticky notes for a month. At five-thirty, my phone rang. Danielle. Her voice had a shape I knew too well: a soft, careful curve.

“Your mother,” she said. “On line two.”

We never talk. We talk twice a year, to make sure one of us is not dead, and even then we keep the details thin. I took the call.

“Zee,” she said, using the nickname that only people who knew me when the world didn’t do. “Your brother.” She swallowed. “Accident. He’ll live. He’s hurt. It’s expensive.”

“Send me the hospital information,” I said, already standing, already moving toward a bag, already finding shoes on muscle memory. “I’ll be there in forty minutes.”

At the hospital, the air smelled like bleach and dread. My mother looked small in a way I had only ever seen when bills lay on the table like unsolved math. She opened her mouth to say we didn’t want to ask but and I stopped her with a gesture I reserve for women who gave me life and insist on apologizing for it.

“I’m here,” I said. “The rest is mine.”

I signed forms that made money move. I texted our general counsel to cut through a stack of nonsense some insurer loved more than breathing. I found my brother breathing in a bed and kissed his forehead and said the things older sisters say to men who think being wounded is a personality.

“You didn’t have to,” my mother said in the elevator, her voice down by her shoes.

“I did,” I said. “But listen to me—this isn’t a ledger. You don’t owe me in soup or silence. I help because I can. You love because you can. We start again.”

She cried in a way that made me want to pick up the whole building and carry it outside where it could never harm her again. She held my hand all the way to the parking lot, and when we got to the doors, she said, “I should have left him earlier,” and I knew she wasn’t talking about dinner in a country club. I said, “You left him now,” and that’s how you give a woman her life back with words you can fit in your pocket.

On the day of our wedding, the rain held back. Quinn and I wrote vows that sounded like we mean it and did not sound like we wanted to impress the internet. We said, I will always be the person you can call at three a.m. without prefacing it with “are you awake.” We said, I will tell you when the work swallowed me whole and I forgot where the shore was. We said, Your mother is my mother. We said, Your board is my board. Patricia did not come. Rachel wore navy and cried into a handkerchief from a generation that knew how to sew. My mother danced with me to a song from a radio station we used to listen to while cleaning offices at midnight and kissed my cheek and whispered, “You were always going to be a house. I am sorry I made you think you had to be an escape route.”

During the reception, which was less about centerpiece flowers and more about a table where each person we loved told one true story, Danielle stood to give a toast. She lifted her glass and did not look at her notes.

“To my boss,” she said, eyes wet and wry. “To the woman who taught me every no carries a yes inside it if you push. To the girl in the warehouse who learned numbers are not just facts; they are weapons worth wielding correctly. To the CEO who understood a termination clause can be a morality clause. To the partner who made my friend brave. To the person who answers email with strategy and cruelty with elevation. May your boardrooms always be full of people who would rather build than brag.”

Late that night, after the last song and the last folding chair and the first pair of shoes I never want to wear again, I stepped outside. The city breathed its damp breath, and the streetlights turned the sidewalk into a runway for people who can fly without planes. A car pulled to the curb. Black. Heavy. Familiar. The door opened, and William Harrington stepped out, his suit a size too big for the first time in his life.

“You look tired,” I said before I could catch the softness.

“Congratulations,” he said, the word like a river stone—polished, worn down, still cold. He looked past me, through the glass, at the party he had not been invited to and would not have come to even if he had. “I didn’t come to make a scene.”

“Then why did you come?”

“To tell you something you already know,” he said, managing a half smile that startled me because it didn’t look practiced. “Pride is a cheap mortgage. You only realize how much you owe when a real bill shows up.”

“You can say sorry,” I said clinically. “It won’t hurt you. It’ll bark.”

“I am sorry,” he said. It did bark. He did not flinch. “For the dinner. For the way I taught my son to measure women. For the way I taught myself to measure myself.”

“I don’t need it,” I said, because truth is a kind of grace. “But he does.”

“I told him,” he said, and here his voice did a thing I did not expect, “that I was wrong to call you what I did. That the only garbage in that room was me.” He glanced down at his hands as if expecting them to have changed in the telling. “Then I came here because I wanted to say it to the person who did not need to hear it from me.”

“I accept,” I said. We stood there and let quiet do what words couldn’t. He looked at the street, at the trees that should not have been able to grow there and did anyway, at the windows of a café across the block that glowed with the particular light only places that serve eggs at seven in the morning know how to emit. He followed my gaze.

“I hear you feed children,” he said.

“I hear you don’t feed your soul,” I said, and regretted it as it left my mouth, and left it because it was true and also because sometimes letting a man know you can still be sharp with him is part of forgiveness.

He nodded. “I hear you own a building that used to belong to a man exactly like me,” he said. “I hear you gave his dishwasher a stake.”

“That’s one way to say it,” I said, and told him about a girl in a yellow jacket and a quiet prayer turned into milk and the boardroom where we voted to make dignity into equity.

“You would’ve made a hell of a daughter,” he said quietly, not looking at me.

“I will make a hell of a mother,” I said, not meaning pregnancy, meaning legacy, meaning rooms where my people could grow without first learning how to shrink.

He exhaled. “Goodnight, Ms. Cross.”

“Goodnight, Mr. Harrington.”

In the years that came after, we built the company we promised out loud that day—the one that did not need a press release to convince itself it had a heart. We made mistakes: we hired a man who could “navigate” regulatory waters and discovered he was a liar; we invested in a flashy AI partner and discovered it was a slot machine disguised as a dashboard. We apologized, publicly and privately. We fixed what could be fixed, composted what could not. We never, ever, called anyone garbage.

We sold products that saved people time they could not afford to lose. We wrote parental leave into policy that made bankers allergic and then converted them. We established a line item for appliances in the budget because our head of engineering cooked for her team and no longer had to buy pots with her own money. We treated cleaning staff like colleagues. We gave bonus checks to an entire building and did not announce it to anyone but the people who live there.

Rachel visits us on Sundays. She brings a quiche that tastes like mid-century grief and a new recipe that tastes like she read a book. She helps me fix my mother’s hair. The two of them talk like women who have seen the part of marriage not covered by veils. Quinn and I fight well and love better. I send Danielle on vacations where she is not allowed to open her laptop. Mei Lin sits on our board and drinks her tea with one hand and tears apart a false argument with the other. William writes op-eds about governance and doesn’t mention me, which is fine because men like him aren’t the point of stories like this.

The Fairchild breakfast turned into a friendship, which turned into a joint lab, which turned into a battery with the highest energy density on the market. A student from our scholarship program stood on a stage in a cap she decorated with glitter that said See you at the board meeting and I laughed so hard I cried and then I cried so hard I laughed. It turns out you can fill a company with people who know hunger at the cellular level and feed them. It turns out profit is not allergic to a soul.

Sometimes, late, I open a drawer and reread a letter I did send—addressed to a girl in Milwaukee.

Dear S.,

If a man calls you garbage, remember this truth: garbage is what the world’s lazy throw at what they don’t understand. The trick is to find the people who pick things up and make them into houses.

Build one. Invite everyone except the people who cannot stop spitting.

—Z.

If you stayed this long, here’s the only moral I’ll permit myself: Power is a room. It is often locked. If your hands grew up learning to jiggle the handle, good. If your hands learned to pick the lock, better. But the best use of that room is not to sit alone counting your triumphs. It is to knock out a wall and call in the people who were told their place is on the curb.

On a Tuesday, in a room that smelled like cinnamon and capacitors, I looked up from a contract and saw Quinn at our kitchen stove, swearing at an egg that would not flip, and beyond him through the window, the city lay out like a schematic. I thought of a night in a dining room dripping with contempt, and a woman who folded a napkin and chose herself. I thought of a yellow jacket and a bell, and a boardroom remodeled by a sentence.

Never again will I ask permission from a man to be worthy of his house. I write the blueprints now. And they all include good light, many exits, and a table where no one is too poor to sit.

END!

News

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

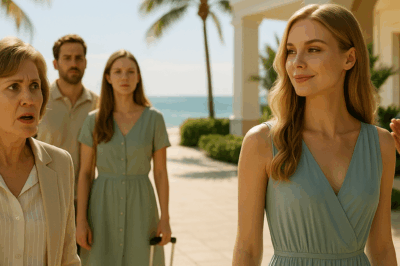

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped “She’s My Boss”… ch2

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped, “She’s My Boss”… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load