My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything

Part One

The bell over the door had a polite little ding, the kind that makes you think of aprons and coffee refills and the radio set low to yesterday’s hits. Most mornings at the Waverly Diner, it signaled the start of something predictable: construction crews in orange vests sliding into booths by the windows, Mrs. Dalrymple ordering “the usual” and then changing her mind, two twentysomething teachers grading papers in red pen while splitting a plate of banana pancakes, Martin in the kitchen making the grill sing. Predictable was how you got through a life that was too big for your hands: rent due on the first, term paper due on the tenth, student loan interest due whenever it felt like being cruel.

She broke predictable in a yellow jacket.

She was a slip of a kid the first morning I noticed her—no older than ten, maybe, but with the fossil patience of a person who has learned to shrink so strangers will look past them. She came right at seven, when the first rush crested and I could breathe. She slid into the booth tucked under the big black-and-white photo of the diner from the 1950s—a picture of a time when pies sat in spinning glass display cases and men in hats leaned on elbows to make their coffee taste like belonging. The girl set her backpack on the seat beside her, spine curved, hands clasped as if holding in a question.

“Egg sandwich, please,” she said, so quietly I had to lean in to catch it.

A minute later I had her order on the grill, the eggs hissing like a happy secret. I brought the sandwich over with a glass of milk because the jacket was too thin, the wrists too bony, the look in her eyes too old.

“Growing bones need calcium,” I told her with a wink I hoped translated to You are allowed to exist out loud here. She didn’t smile. She looked at the door, chewed, looked again. When the check came, she counted quarters and dimes with the reverence of a person doing math in emotional weather. She came up a dollar seventy-four short. I replaced the difference with two dollar bills from my pocket and tucked the check under the syrup caddy as if it had paid itself.

The next morning she came at seven. Yellow jacket, backpack, “egg sandwich, please.” This time the coins were crumpled, warm from being clutched too long. I threw in the milk, because I am a woman who believes in rituals built from pennies. Day three the pattern cemented, day four the silence frayed into something that wanted to be a voice, day five I put an extra napkin within easy reach because her sleeve cuff was starting to shine with dried milk and embarrassment, day six my boss noticed.

Rick hates surprises unless they benefit him. He sharpened that scowl on the whetstone of his own insecurity, the kind men wear like cufflinks in places where tips add up to rent, and he aimed it at me across the service window as if the force could alter reality.

“What’s that table got?” he barked.

“Egg sandwich,” I said, sliding a plate onto the pass. “And a glass of milk.”

Rick leaned into the window. His breath smelled like nicotine gum and ashtrays. “The kid in the corner again? You comped her yesterday.”

“I closed it to my check,” I said. “It didn’t touch the books.”

He stared. He has a way of staring that makes you feel like you’ve transgressed even when you know you haven’t. “Not our problem,” he said flatly. “You comp her, you pay. And don’t be cute, Vera—there are always more people with your skill set than there are jobs.”

He didn’t say you are replaceable; he hung it in the air like a wet coat you were expected to put on.

I signed his warning slip in the back office that afternoon anyway. It smelled like cold coffee and impatient men. The form’s language was as bland as oatmeal—unauthorized discount, violation of company policy,—but it had Rick’s satisfaction pressed into the ink. I printed V-E-R-A where my name belonged and felt my hand shake.

That night in my studio—just wide enough to hold a bed and a future if you stood carefully—I redid the math of all my choices on the back of a syllabus. I could not afford to lose the job that paid the rent for the place where I studied until my eyes watered and the words doubled on me. But I could not stand in the doorway and block a child from breakfast for the sake of a rule meant for people who didn’t understand that kindness is sometimes the only way to remember you are a person in a world that likes to make you a function.

In the morning, I taped two dollars to a Post-it and tucked it inside my order pad. When the bell chimed at seven and the yellow jacket appeared, I exhaled a prayer that I did not believe in to a God I was cautiously on speaking terms with again and started her egg sandwich. After she ate—not hungrily, exactly, but with that tense, cautious efficiency of someone who never trusts that bites remain once you take your eyes off them—she slid a note under the milk glass and scurried out in a flash of yellow before I could put any of the correct feelings into the world.

Thank you for the milk.

The letters were big and careful. The loop in the Y was too big for the line. There was no signature.

I tucked the note into the pocket inside my apron like it was a relic, the kind you touch when you need proof that the thing you did mattered to someone besides the person who told you not to do it again.

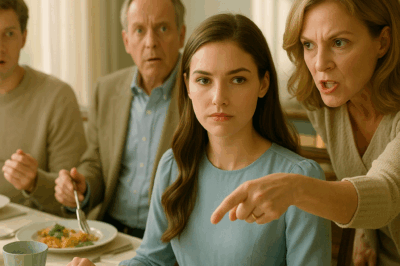

On the day everything exploded, Rick chose the moment when the diner was as full as a church after a storm. The bell dinged and dinged. Mrs. Dalrymple complained that the morning news had gone soft. The construction crew ordered the sandwich that requires three hands to assemble. Two high school kids with heavy backpacks and hopeful eyes requested a corner with an outlet and I directed them there with a kindness that cost me nothing and paid them enough to try to retake the math test they had failed. At precisely 7:01, the yellow jacket tugged the door open. I mouthed Hi over the head of a man who would use five sugar packets to sweeten the bitterness of his own life if he could, and she gave me that almost-blink that we had taught each other to read.

Rick watched me start her sandwich. I know because I felt his disapproval condense into weather.

He waited until I set the plate down in front of her. Then his voice rose through the diner like a siren.

“You know she can’t pay, yet you serve her anyway. You want your wages docked?”

Forks froze midair. Heads snapped like birds startled into flight. The little girl flinched so hard her backpack strap slipped off her shoulder. My face burned—an odd thing to notice in real time. Shame is supposed to hit later, when you try to wash it off. This shame burned in the moment. I saw myself how he wanted them to see me: foolish, rule-breaking, soft, unprofessional. I saw the girl see herself the same way, but worse: as the reason for adult anger, as the center of public disapproval, as a problem that could be solved by making her smaller.

“She’s a child,” I said, keeping my voice level, the way you do when a cup of coffee is too full and you need to carry it to a table without spilling. “I’m not letting her go to school hungry.”

“Not your problem,” he snapped, and in the back of the diner, Dany lifted her phone and tilted the frame to get me and the yellow jacket in the same shot—grist for the staff chat that will outlive all of us. “No more freebies or it comes from your check.”

The child sprang from the booth like a startled bird and fled. For a moment, the door was nothing but a rectangle of winter light.

“In my office,” Rick barked.

I signed whatever he put in front of me while he monologued about margins as if they were the commandments Moses brought down from the mountain. When I left the office, I took the long way to the coffee station and breathed behind a stack of mugs until the air found me again.

The next morning was a drumroll. Seven came. No yellow jacket. Seven-ten. No yellow jacket. I poured coffee with a smile and refilled maple syrup with a steady hand and kept glancing at the door as if my eyes could conjure a child into safety. At eight-fifteen, the diner’s atmosphere changed—as if someone had opened a window and let a bigger world in.

It began with the black SUV easing to a stop at the curb. I recognized expensive when it idled, and this was expensive that did not bother pretending to belong on our block. Two men in suits got out first, not in that way men in suits get out when they want to be seen but in the way professionals move when their job is to measure spaces in six directions and decide where to stand. They scanned. Then they opened the rear door.

The man who ducked out was tall and tailored and carried a hush around him like a friend. The hush entered with him, pressed down the radio and the forks and even Rick’s insistence that nothing interesting happened at the Waverly. He walked in like he belonged wherever he chose to put his shoes. Two more suits flanked him—professional, not performative. Rick wiped his hands on his apron and plastered a smile onto his face as if he had invented hospitality.

“Good morning, sir,” he said, moving toward the man with the practiced glide of the small-time overseer. “Welcome to Waverly Diner. How can we help you?”

The man’s eyes—sharp, assessing, blue-gray like the city an hour before a storm—swept the diner once. He did not look at Rick.

“I’m looking for the person who’s been helping my daughter,” he said, and I heard at least three forks clink quietly onto plates.

My hand put the coffee pot down without consulting me. “That’s me,” I said, stepping out from behind the counter before I could calculate how that might endanger my job. “I’ve been serving her.”

He turned fully then. It is a strange thing to be studied by someone whose face you have seen in magazines you thought were for people who fly in private rectangles of sky. In the space of a breath, his expression shifted—cool control giving way to something like grief that had not been allowed to speak out loud for too long.

“She hasn’t eaten breakfast outside our home,” he said, “since her mother died.”

The diner inhales and exhales with the regularity of a heart. It held its breath. The coffee hiss softened. Outside, the bus decided not to grumble just then.

He took a slim piece of paper from his breast pocket and unfolded it in a motion that told me he had done that gesture a hundred times in the last twelve hours. The contents were familiar; I had ironed them flat in my own mind all night.

You’re the only one who talks to me without being scared. I like the milk every morning. Thank you, E.

“Nathan Fraser,” he said, holding his hand out with the half-apology of a person who knows his handshake opens doors and has grown weary of the ones that do. “Emily is my daughter.”

I knew his name. You could not be a student of systems—as I was in night school, writing papers about the ethics of scale—and not know the billionaire who had built something on a blueprint of math and mercy. Philanthropist, investor, the kind of man who could buy continents if he wanted to and had, instead, purchased libraries.

Before I could get my name onto my tongue, Rick piped up like an obliging chorus. “Mr. Fraser! Big fan. We love having your daughter. I personally—”

“My security team overheard a different story,” Nathan said without looking at him. The temperature in his voice did not change. The room felt it drop ten degrees. “Where is Emily today?”

“At home with a cold,” he answered himself, turning back to me. “She was upset to miss breakfast. She asked me to find the waitress who talks to her like she’s a person and tell her…” He trailed off, swallowed, then found the words again. “Tell her thank you.”

I had nothing worth saying in a diner full of people who now knew too much about the creaking hinges of my heart. “I didn’t know,” I managed, and the inadequacy of it lit my face with useless heat.

Nathan’s gaze softened. “You did something most people forget is possible when life gets loud,” he said. “You noticed what mattered and chose it.”

Rick decided the moment had gone on too long without him being in it. He sidled closer, voice syrupy. “You know, Mr. Fraser, I personally instructed my staff to—”

Nathan lifted his hand, palm out, and Rick stepped back as if a wall had materialized. “Not necessary,” Nathan said. He took a business card from the same pocket that held Emily’s note. It was matte, weighty, tasteful. The kind of card that could slice if you ran your finger too fast across it. He held it out to me between forefinger and thumb like you would extend a piece of medication you knew the other person should take on an empty stomach.

“If you’re interested in opening something of your own,” he said, “I would like to finance it. Fully.”

It is a rare gift for a sentence to change the temperature of your cells. That one did. Rick wavered in my peripheral vision. Dany lowered her phone. Martin’s face appeared in the service window, eyes shining like a child’s when you tell him he can ride the front seat of the truck.

“Why me?” I asked, because we are taught to suspect the improbable even when it is wearing its credentials like armor.

“Because you fed my daughter before you knew who I was,” he said. “Because people like you are the infrastructure companies like mine pretend to build but often forget to fund. Because I can.”

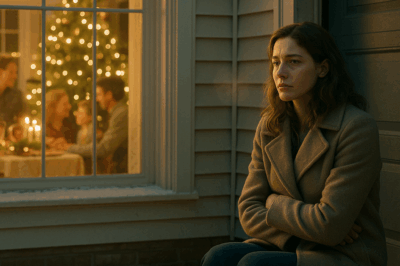

The bell over the door chimed. A flash of yellow. Emily, small and quiet, tucked herself into the space at her father’s side like she had always belonged there. The woman with her—the caretaker I would later learn called herself Ms. D and made grilled cheese like therapy—hovered, unsure.

Emily looked at me. Not past me. Not through me. At me. The look felt like being stamped into someone’s life.

“Will you still have egg sandwiches?” she asked.

It was the first time I had heard her voice in a tone that allowed for hope.

“Every day,” I said, and my own voice broke on the second word, because sometimes gratitude arrives with the grace of the thing you’ve been starving for. “Forever and a day after that, if you want them.”

She smiled, a fractional lift that would have been invisible if I hadn’t been watching for it. It moved something under my ribs I realized I had not allowed to move since my mother left me at the shelter at thirteen with a clear plastic bag holding a pair of jeans and a book I could not read because crying makes words swim. I looked at Nathan’s card in my hand. It had his direct number on it.

“I’ve never named anything,” I said, half to him, half to the kid who had written a note that had reopened a room in my chest. “If we do this, we call it E&V Mornings.”

“Then go home and make a list,” he said, and his relief looked suspiciously like joy.

We shook hands. The diner remembered how to breathe. Rick remembered how to seethe. The construction crew clapped once, a single beat like the crack of a pool cue, and then, respecting the privacy of the moment, started their own conversations again. Emily let me tuck a napkin into the collar of her jacket. Ms. D told me she’d bring her again tomorrow if the fever broke. Nathan nodded to his men. The black SUV idled outside like a very patient animal. I slipped the business card into the hidden pocket of the apron where the milk note lived like a talisman.

Three weeks later, the sign above the little storefront six blocks from the Waverly was the yellow of Emily’s jacket and the font of my own handwriting. E&V Mornings.

Opening day, the bell over the door sounded just enough like home to make the first child through the door exhale relief and the first woman who saw the chalkboard art smile the way people do when something small tells them life is going to be okay. We had poured the walls the color of toast. We had hung secondhand chairs from a church sale and rubbed them with lemon oil until they remembered they were dignified. A wooden rack by the door held backpacks. A shelf in the corner held library books with E&V stamps on the inside cover so they would come back to us even if the kids forgot to.

At seven that morning, the first person in line was Emily, wearing a hair clip she would later confess made her feel like a person who could speak in full sentences without apology. She held my hand on her side of the counter while Martin—the only one from Waverly I was eager to hire—made the grill sing our new song. I insisted the menu be simple enough to memorize and flexible enough to allow the day’s kindness to find the gaps. Suspended meals: we wrote it on the chalkboard. A jar on the counter: “Pay for a student’s breakfast if you can. Become someone’s miracle if you want.”

Nathan came exactly as often as kindness looks like letting the people you love build their own rituals without turning them into performance. When he came, he sat in a corner with his laptop and watched his child refill the napkin caddies. The first week, he sent a health inspector I had not yet learned to fear; she left with a receipt and a bag of cookies. The second week, he sent a sign guy who made our outdoor sandwich board look so good I wanted to put it on my mantle. The third week, he sent a lawyer; the lawyer left with a packet of pro bono paperwork for a woman in the neighborhood whose landlord thought “month-to-month” meant “I can pick any month.”

A reporter came and wanted to call me a Cinderella with a stainless-steel spatula. I said no to his trope and yes to one photograph only if it also included the sentence I had written on a napkin at two in the morning that felt like a mission statement: No child turned away. All students welcome. He put it in the story. We got three crates of oranges delivered the next day from a produce guy who wrote his cell number on the invoice and said call me if you ever need juice when the juice money is funny.

Rick came once. Stood across the street with his hands deep in his jacket pockets like he was afraid the cold might make him lose his grip on the version of the world where he was right. When our eyes met, he looked away, then looked back, then shook his head in a gesture I couldn’t translate. I had imagined I would want to savor his discomfort the way you lick the spoon after icing a cake. Instead, I felt something like pity and a kind of thank you you don’t say out loud because it would sound like gloating: If you hadn’t humiliated me, I might not have remembered I deserved a life built on my own rules.

One afternoon, two months into this new life, a boy with the loose-limbed hunger of a puppy wandered in, eyes on the floor, shoes talking to each other at the toes. Emily lifted a plate from the pass with the careful hands of a nurse and set it in front of him without asking. Milk followed like a period at the end of a sentence. He looked up, startled, then took a bite like he thought it might hurt him. It did not. He chewed. He swallowed. He put his shoulders down. Emily put a book on the table and tapped the page and said, “This part’s funny,” like a person who remembered someone had read aloud to her once and the memory had slid into the room and sat down to be held.

I found a corner and cried quietly into the broom closet because sometimes the sight of a child remembering they are not a burden drops you to your knees.

By the end of the first year, I had learned that running a café is a dance between inventory and grace. Flour shows up late the morning a bus of fourth-graders arrives unexpectedly. The espresso machine sulks because it is cold. The ovens burn the first batch when you’re thinking about the math midterms you have at eight p.m. and you forgot to set a timer because you thought muscle memory would get you through. A man comes in angry because he thought our suspended meal policy was virtue-signaling, and he leaves an hour later having paid for five breakfasts because a child told him, without meaning to change him, about the way it feels to take a test with a stomach that is not eating itself.

Nathan’s lawyers drew up leases and loan documents and terms that protected me even from my own desire to be more generous than spreadsheets believe is wise. He said his name did not belong on our door, and I said okay except for the plaque in the back hallway where the staff hang their sweaters. It reads: To E&V Mornings, with gratitude for teaching me the math I forgot to believe in. —N.F. The cooks rub it with their sleeves for luck.

At the party we threw on the café’s first birthday—a thing with balloons and carrot cake and a song someone had written about eggs that made us all laugh until the edges of grief softened—Rick came again. He waited until the crowd thinned, then walked in as if the bell over our door were heavier than the one he used to ignore when I needed a break.

“I was wrong,” he said without preamble. His face looked like a man who had practiced this sentence and found it tasted like medicine.

“Yes,” I said, because sometimes being kind means you don’t pretend a different sentence happened.

“I—” he faltered. “Do you—could you—” He didn’t know how to say hire me without choking on the part where I would have the power he used to hold. I didn’t make him say it.

“We need a dishwasher on Saturdays,” I said. “And we need someone to mop who understands that bleach is not better, it’s just louder.”

He blinked. “I… know how to mop.”

“Good,” I said. “Show up at six.”

He did. He never once raised his voice in our kitchen. He kept his eyes on the tile and the sinks and his hands on the work. He brought in a plant and set it in the window above the dish pit like a small rebellion against the part of his life that had thought sunlight was for other people. The first time I saw him hand a suspended meal ticket to a teenager in a hoodie, I turned away so he could keep his dignity in the frame. Two months later, he brought his son in for pancakes and sat in the dining room and let the boy leave powder sugar fingerprints on the tabletop without flinching.

On the day I took my last exam for night school—Ethics in Organizational Leadership; I got an A because the professor was a human being and I studied until the truth stopped blurring—I locked up the café and walked home in air that tasted like snow and opened the note I had been saving in the pocket inside my coat. Emily had written it the first morning she spoke in a voice that carried easily enough to hear without leaning in.

Milk and kindness taste the same to me now. —E.

Her father’s identity opened a door I could not have pried with my bare hands. The bigger surprise was that it did not change as much as everyone thought it would. We would have made egg sandwiches for Emily without a billionaire. We would have found a way to tuck one more kindness into the corner of a café that smelled like butter and dignity. But because Nathan’s name turned bankers into allies and inspectors into reasonable people, we did it faster, cleaner, with fewer nights lying awake redoing the math of our own risk.

On the bench outside the café, Emily and I still sit on Tuesday afternoons and practice our respective homework. She writes sentences about whales and weather and how people carry their fear in their shoulders. I write case studies about false equivalencies and hiring practices and how people carry their shame as pride. Nathan reads in the corner when he can, his head bent in the posture of a person who has built something so big he has to remember to be small on purpose.

“I like our sign,” Emily said recently, tapping the painted board by the door with the side of her sneaker.

“Which part?” I asked, watching her choose her words with the care of an artist picking the right color.

“‘No child turned away.’” She paused. “That means me.”

“That means you,” I said, and she smiled the kind of smile that moves everything.

One night after we had closed and turned the chairs upside down on the tables and counted the register drawer and restocked the syrup bottles I like because they make a funny sound when you pour, I walked to the door and flipped the sign to CLOSED. In the reflection, I caught a glimpse of the woman I had been in Rick’s office when the world pressed its knee into my throat and told me to sign quietly. She is still with me, that version of me. I measure my choices against her like a yardstick: will this make her proud? If the answer is yes, I do it. If the answer is no, I step back from the stove and let the air clear.

That night, I stood for a long time with my hand on the glass and considered a truth bigger than the diner, bigger than the café, bigger than the billionaire whose name started this chapter of the story: we are not guaranteed justice. But sometimes, when a girl in a yellow jacket puts a note under your milk glass, every choice you make after that becomes a sentence in a paragraph that adds up to something like it.

Her father’s identity changed everything and nothing. It bought ovens and lawyers and men who know where to stand in crowded rooms and the patience of permits. It did not change the fact that a person with a mouth can use it to cut or to feed. It did not change the way the bell sounds when a child who used to look at the floor walks into a room like she expects to be welcomed.

In the morning, we will write the special in Emily’s improving cursive. Martin will burn the first batch of toast because he is thinking about his granddaughter’s piano recital. Rick will mop like penance. Nathan will text Ms. D a picture of the lost-and-found basket because he is, at heart, a father. I will pour a glass of milk and set it by the register so I remember where this began. And when a kid with their life in their backpack walks in, we will take one look at the way they are holding their shoulders and know what to do.

Every day if they want. Forever and a day after that.

Part Two

The first time a news truck idled at the curb outside E&V Mornings, Emily was the one who noticed.

She tugged my apron while I was restocking the to-go cups and pointed to the window with the quiet urgency I had already learned to trust. A camera lens winked from the passenger seat. Another crew set up across the street, the correspondent’s hair resisting the same wind that kept trying to smudge the chalkboard specials Emily had written in careful block letters: Egg Sandwich $4.50. Milk $1.00. Cinnamon Toast $1.75. No child turned away.

“You don’t have to talk to them,” Ms. D murmured at my elbow. She had a way of appearing exactly where your nerves needed her to be. “Nathan told them you prefer not to.”

“I don’t mind saying one thing,” I said. “But this place isn’t going to become a photo op.”

We kept serving through the knock and the bell and the murmur; it felt important not to let spectacle become the boss of the room. The correspondent waited until the line thinned, then slipped inside with a smile that looked like it had been professionally whitened.

“Ms. Sullivan?” she said, holding the microphone like a lily. “Do you have any comment on the story?”

“Only this,” I said, wiping my hands and stepping out from behind the counter because sometimes a sentence does more good when you carry it around the room with you. “People have been feeding people since the beginning of time. We are not special. We’re just organized.”

She blinked, not sure how to fit that into a segment scheduled to run between a sports update and a weather spot. “And Mr. Fraser’s role—”

“He’s a father,” I said. “This is a neighborhood. Those two facts are more important than anything else.”

We went back to service. The camera caught Emily bringing a plate to the boy with the talking shoes, caught Martin shaking cinnamon sugar over toast like you would dust a story with magic, caught Ms. D setting a glass of water within reach of a woman whose hands were shaking because shoplifting charges look like hunger from the inside. The piece that aired that night was less about money than I feared and more about the hum of a room where people were not required to perform their need.

The next week was our busiest yet. The construction crew started sending a guy ahead to hold a table with his jacket. The teachers learned to bring their own pens because ours kept walking home in the pockets of second graders who thought red ink might make their handwriting brave. A woman in a leopard-print coat who had never in her life eaten toast without guilt paid for twenty suspended breakfasts and cried into a napkin with a flower printed in the corner because she remembered being nine and drinking milk that tasted thin.

Not all the attention felt like a blessing. The part about Nathan being Nathan leaked anyway—it always does when money rubs its elbows on anything tender. A man with a podcast nobody should have to listen to lined up photographs of me, a latte art tulip, and a headshot of Nathan on a split screen and said the word gold-digger three times as if repetition could write history. Somebody snapped a picture of Emily outside the café and posted it with a caption about “heirs with heart” that made my skin crawl because children do not exist to humanize their fathers for strangers’ clicks. A fashion blog helpfully linked to my thrifted cardigan as an “affordable dupe” for a sweater someone had worn on television, and I hated that even my sleeves could be turned into marketing if I didn’t hold my arms close.

Nathan’s team offered to spin it. He has people who build fences with sentences for a living. They prepared statements about “community partnerships” and “impact” and “grass-roots initiatives.” I read them and felt the familiar high school cafeteria click in: how even your most generous words can become exclusionary if you let them wear the wrong shoes.

“We’re okay,” I told him on the phone that night, sitting cross-legged on my studio’s threadbare rug, textbooks open like small, demanding children around me. “We have our sign on the wall. We have coffee and eggs. We have kindness. I don’t want a press kit.”

He was quiet on the other end. When he did speak, his voice was the version he reserved for the people who did not ask him to be what the world believed he was for rent. “Thank you for telling me no,” he said. “I need someone who isn’t afraid to.”

The more crowded our mornings got, the more the landlord’s eyebrows lifted when he came in after closing to “fix” things that did not want his help. The building had been cheap because the pipes liked to sing arias when no one asked them to and the back door required three curses and one shoulder to open. Now, suddenly, investors sniffed up and down our street like dogs who had found a peanut butter jar. One Tuesday, I came in at 5:30 to watch Martin prime the grill (he likes to bless it with bacon grease the way some people anoint a baby) and found a letter slid under the door.

NOTICE OF LEASE TERMINATION.

I read it so quickly I dropped a clause and had to pick it up.

“Sixty days?” I said aloud, and paper never answers you. The reason cited was “renovations and strategic re-tenanting” which is landlord language for we found someone with deeper pockets who doesn’t hang prayer flags in the corner and we would like to make more money now.

I called our lawyer first because I am finally the kind of woman who does not delay hard tasks until after she has cried. He said we could fight on technicalities and win months, maybe, but not the war. I called Nathan second.

“I can buy the building,” he said before I finished. His instinct is to fix by building a bigger foundation. It is not a bad instinct to possess, and it has, in fact, saved libraries.

“You could,” I said, the way you say a hurricane could because power is power. “But this corner wasn’t supposed to be conquered. It was supposed to be kept.”

“Tell me what to do instead,” he said, and I heard Emily in the background laugh at something Ms. D had said, and the choice became very simple.

“Help me make a lot of very small owners,” I said.

By the end of that day, the chalkboard by the register held a new message underneath the suspended meals tally: Help us buy our mornings. I didn’t want crowdfunding that felt like pity. I wanted co-ownership that felt like the backbone of a city. We drew a little map of the building with a Sharpie: our unit shaded yellow, the hair salon next door in pink, the tiny florist in green, the apartments above in gradient grays. I wrote numbers on the board and swallowed twice because $1.1 million feels like the difference between eating and seeing your own ribs.

“People are tired,” Ms. D said as we laid copies of the co-op proposal on the counter like placemats. “They might not give because they already gave everything to survive this year.”

“Then we make it worth more than money,” I said, combing through the pamphlet for language that would tell the truth. “We make voting power. We make stewardship. We make a room where the bell will still ring for this kid when she is fifteen and practicing for a science fair.”

We launched on a Saturday. It rained the way this city does when it wants to move moss down a street. We put a rug on the floor so the kids’ shoes wouldn’t slide when they danced to the song that the boy with the talking shoes insisted Alex Turner had written about French fries. The first contribution was twenty dollars in dimes and quarters from a group of people who always set their drinks to the left because the scar on their right hand hurts when they reach across. The second was a check for $50,000 from a woman with old money and a new moral compass that points to make up for your father. The third was from Rick, who brought in a cigar box filled with cash that smelled like regret and lemon cleaner.

“From the dishwasher fund,” he said gruffly, placing it on the counter and refusing to let me see the tears in his eyes by using both hands to adjust his hat. “I figure I’ve rationed out eighty years of people’s dignity. Figure I owe some of it back with interest.”

Nathan wanted to write a check to end it. He said as much and then swallowed the urge when I asked him to imagine a wall full of names instead of the single-letter kind of ownership he moved through the world with like a natural disaster. In twenty-one days, we raised the first $500,000. In forty, we had enough signatures to make a bank believe a café could be a fortress. The hair salon added a barber’s chair out front and cut line cooks’ hair for free if they promised to tip two dollars even when the math scared them. The florist chose plants that thrive in neglect and donated one for every hundred dollars raised with the admonition please be kinder to this than you are to yourself. The apartment tenants upstairs formed a tenants’ council and started bringing down their compost in little buckets we kept in a neat stacked pile by the back door.

We closed on the building on a Wednesday that had the audacity to be sunny. The deed listed forty-seven owners: baristas and grandmothers and a math teacher and a kid who ran his lawnmower up and down a whole block all summer and a billionaire whose name appears last in the smallest font because he asked.

The day after the papers were signed, a letter slid under the door addressed to me in handwriting I had seen before on tip jars and warnings about health inspectors. It was from Rick. It read:

Dear Vera,

I used to think rules were how you kept a restaurant clean. I was wrong. Rules without mercy are just aprons you use to wipe your conscience on. Thank you for letting me learn this with my hands in hot water. P.S. The mop bucket leaks. I fixed it. —Rick

If this were a movie, the next scene would be about money going to people who needed it and endings sewn up like hems. Real life is sauce you spilled on a white shirt and pretended was a pattern. The day after we bought the building, the health inspector came with the clipboard and the stern eyebrows and a hole in her shoe where the sole had started to flap. She cited us for a cracked tile by the dish pit. We replaced it that afternoon because you can love justice and not want bacteria to grow its own city under your feet.

A week later, a man with opinion hair from the same podcast sent a camera crew to “expose” the billionaire “using a café to launder guilt.” He tried to catch me on the sidewalk between trash bags and called me a parasite in a tone usually reserved for women who become congresspersons. I did not answer. The internet answered for me with photographs of Emily’s careful printing on the chalkboard and a paragraph someone’s grandmother wrote about the years during the war when everyone fed everyone because there was no other way to make it to morning. The man’s podcast episode tanked. I do not know if he ever learned to spell grace.

Spring laid a soft hand on our block and then removed it and then put it back because that’s how April makes decisions. On a day when the rain couldn’t decide what it wanted to be, Emily sat at the counter and watched a woman approach the register with a look on her face I had seen too many times: that scuffed, steel-colored combination of hunger and shame.

Emily reached under the counter for a suspended meal ticket, printed in the same careful all-caps the chalkboard specials wore, and laid it on the wood deliberately. “Milk and toast?” she asked, voice steady. The woman nodded without trusting her jaw to hold a thank-you without breaking open. Emily filled the glass, placed the plate, and walked away so the woman could stare at her own hands as long as she needed to.

When Emily came back to the counter, she did not look at me. She lifted her chin a millimeter, and I understood that we had passed some threshold that only the two of us could see.

“Do you remember,” she said, the words purposeful and brave like a person stepping across a creek on a slippery rock, “when I wrote the note?”

“I do,” I whispered, and it was true in the way that tastes are true; I could still feel the paper against my thumb.

“I wrote another one,” she said, and slid a folded square across the counter. I opened it. The letters were smaller now, as if her voice had learned to fit in tighter spaces. I am not scared of doors anymore. —E.

I leaned across the counter and kissed the top of her head because there are moments when all your sentences should be replaced with gestures.

There is a photograph on our wall now—it hangs next to the note Emily framed for me the morning she wanted me to have proof of the magic I was making. In the photograph, I am standing at a folding table in a community center under fluorescent lights, wearing a cap and gown over an apron that makes me look like I am a waitress at my own commencement. Night school inched me across the stage in sneakers that cost less than a textbook, and as I shook the dean’s hand, the professors from Ethics and Organizational Leadership clapped like I had given them permission to write a new exam. In the photograph, Martin stands on a chair in the back to take a selfie with me and half the café in the frame. Ms. D cried so hard her mascara left comet tails. Emily held her hands in her lap the way you do in church when someone is giving thanks, and after the ceremony, she looked at me for a long time and said, with solemnity disproportionate to the sentence, “You did the hard math.”

Two months after I graduated, the school district called. The superintendent’s voice had the weary brightness of a person who has been told to do more with less so many times the phrase has etched itself into her blood. “We have a situation,” she said. “The state cut funding for breakfast pilot programs. We have children who learned how to learn because their stomachs stopped gnawing at their spines, and we have no money to feed them.”

“We are not a government agency,” I said, because the ethics professor lives in my head now and knocks me into better thinking when I am about to set myself on fire to keep a room warm. “We cannot be the budget gap. But we can be the bridge.”

We wrote a plan that read like a recipe: a little grant-writing from the school board, a matching fund from our suspended meals jar, a low-margin contract per plate because dignity means you do not discount the labor of the hands that crack the eggs. Nathan offered to write a check with enough zeros to make the superintendent weep into her cardigan. I let him add one zero and turned the rest into a pledge to match community giving, because help that looks like partnership tastes better when it is in your mouth. In September, we fed two hundred children breakfasts the school could not afford to give them without making the teachers bring their own peanut butter from home.

On the first morning of the partnership, Rick came in before dawn with mops and buckets and a seriousness that made me step out of his way. “I want the floor to shine when those kids walk in,” he said. He had thought the redemption arc would be a montage. It turns out it is just getting up earlier and sweating for people who will never know you used to be a person who made mothers cry in public.

This is not the part where I tell you Nathan and I fell in love because I took a business card from his hand and because the internet decided I was Cinderella with a spatula. We did not. He is a man who loves his daughter and his work and the feeling of carrying less money in his heart than you would imagine. I am a woman who loves her café and her textbooks and the sudden understanding, at twenty-eight, that you can build a life without marrying a person who could fund your dreams and ruin them in one signature. Sometimes he stands at the counter and drinks his coffee black and says, “You could run my company,” and I say, “I can barely keep flour in stock,” and we both smile because we know the sentence means I trust your brain with the thing I love most besides my child.

We still have slow days when the soup doesn’t sell and I wonder if I should have made tomato instead. We still get the occasional letter calling us socialists in handwriting that looks like it crawled out of the bottom of a conspiracy theory. The health inspector still checks the gasket on the fridge with more zeal than the part of me that hates mildew thinks is necessary. And some mornings, Emily still sits at the back table with her jacket sleeves rolled up and her hands clenched for a reason she can’t explain. She rings the bell when she is ready to speak. We come to her then, always. This is how you teach a person she does not have to shout to be heard; you move your ear closer.

On our second anniversary, we held a block party. We hung strings of lights whose bulbs somebody’s uncle had labeled with a Sharpie in 1998. The florist made bouquets from everything that grows in this climate without complaint and stuck them in jars on the tables. The hair salon set up a mirror on the sidewalk so people could see themselves looking like the best version the world had not let them remember they were. The teachers wrote YES, you do belong at the AP meeting on index cards and tucked them into backpacks as if hope were confetti. The city sent us a permit that made no sense and a cop who did not supervise at all unless you count dancing as enforcement.

Nathan stood off to the side like a man who can pay for everything and has learned not to try. When we cut the cake—a layer that tasted like cinnamon and second chances—Emily cleared her throat the way a person does when they are about to unfurl a flag.

She climbed onto the little step stool behind the counter. The room quieted the way I have seen it do for funerals and for the first time you say I love you loud enough to get caught in public.

“This place,” she said, her voice carrying in that miracle way that happens when you add certainty and a room full of people who want to hear you, “is where I learned milk and kindness taste the same. It is where doors stopped being about leaving. It is where I stopped being scared of forks.” She flushed, the way ten-year-olds do when they reveal a private joke to a crowd; we cheered gently, laughing with her, not at. “Thank you for making mornings,” she finished, and then ducked her head into my shoulder and let me hold her while the block pretended it had allergies.

When the sun dipped behind the rooftops and the lights over the street encouraged us to believe that night could be soft, I took a photograph with the disposable camera Martin had insisted on because he didn’t trust the cloud. In the frame: Rick wiping down a table with the reverence of a man turning a page. Ms. D putting her hand on a boy’s back who needed a path to the bathroom that was less scary than the one he had been given at birth. Nathan, hands in pockets, watching his daughter become a person who belongs to herself.

We hung that photograph next to the plaque with the words Nathan asked us to include. The plaque reads: We bought this building together because belonging should not be at the mercy of someone else’s spreadsheet. —The Owners of 713 Belden. There’s a little arrow drawn in Emily’s handwriting that points to the word Owners. She likes the truth of the plural when she passes it with her jacket unzipped.

At closing that night, I flipped our sign to CLOSED and stood again with my hand on the glass. “Aren’t you tired?” Ms. D asked, coming up beside me in a cloud of lemon and soap.

“Yes,” I said honestly. “But I am tired in the way you are at the end of a good book. It’s the kind of tired that knows you will miss this when it’s done.”

“Good,” she said softly. “Then you’re doing it right.”

Sometimes, late, after the spoons are stacked and the chairs turned and the bell sits quiet against the door, I find myself replaying the morning in the Waverly when Rick’s voice tried to make me smaller. I think about the way the little girl’s shoulders rounded when adults used their mouths to move air like weapons. I think about how easy it is to give in to the kind of compliance that makes neglect into a policy and hunger into a principle. And then I write in the margins of my textbooks in three different colors: remember the yellow jacket. remember the milk. remember the note.

Her father’s identity reordered the labels on the map we use to get permits and fight landlords and scare off people with clipboards. It did not make the eggs cook, or the doors open, or the bell ring. We did that. Emily did that. The janitor did that. The teacher counting out quarters for a student’s breakfast did that. Rick did, with a mop and the word wrong hanging brave in his mouth for the first time.

If the question that launched this story was What happens when your boss threatens to fire you for feeding the kid in the yellow jacket? the answer turned out to be You build a morning that can’t be fired.

Tomorrow, we will open at seven. The iced coffee will drip with improvised precision into the mason jars we keep because it makes the espresso feel like it belongs to someone’s grandmother. The math teacher will sit by the outlet and grade papers in green pen because red feels like violence sometimes. A boy with talking shoes will ask if he can use the back for a job interview; we will say yes and make sure he leaves with a button that isn’t missing. The city will ask too much of too many people; we will ask for another round of suspended breakfasts. The bell will ring; we will lift our heads from whatever grief we have been carrying and decide again to be soft.

And somewhere at seven-oh-one, a yellow jacket will tug a door open, and a place will answer with a plate and a glass and a woman behind a counter who knows that rules are for the floor tile and mercy is for the rest of us.

END!

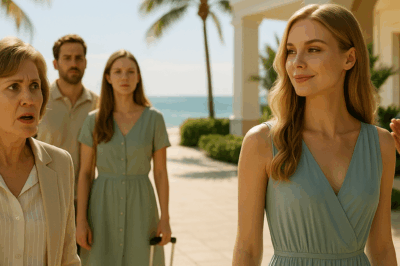

News

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped “She’s My Boss”… ch2

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped, “She’s My Boss”… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load