My boss made a rule that he instantly regretted

Part One

Tuesday began like any other Tuesday at Halcyon Data—too many breaths taken inside too-small offices, the hum of servers like a nervous insect behind the plastered conference rooms, the caffeinated clatter of keyboards playing a soundtrack to the day’s anxieties. We were a company that sold confidence in numbers: models, uptime guarantees, presentations scripted to smooth away panic. The idea was that when things went wrong out there, our charts and contingency plans would make people unflinch. Inside, of course, things rarely matched the sales deck.

I had been at Halcyon for six years. Not the kind of six you boast about on Instagram—the kind that expands quietly until your life bends around the workweek. I started as an analyst, learned how to speak politely to servers that refused to be polite back, taught myself the syntax of backend maintenance while listening to podcasts about life coaches and leadership. Somewhere along the way I became the person the company called when something bad happened. It was not a title on my business card, just the way people looked at my desk when their day unspooled into a crisis.

That Tuesday the entire system crashed and twelve investors sat in our glass-walled conference room, fresher than I am in mornings and colder in their expectations. When the backup failed we watched, collective breath held, as dashboards flattened and a throat-tightening alert exploded across every monitor. The boardroom was a stage and we were the cast that had forgotten their lines.

I saw the clock on the wall, the hands sliding with an indifferent dignity. I saved the work I had open, methodically—a reflex. Habit is the thing that keeps you from turning your life into a pile of ruined files. Then I started packing my bag. It was my policy to leave on time. Years in tech have a strange culture of this: we develop on the edge of exhaustion and enforce rituals as if rituals were guarantees. My manager had recently made a rule meant to protect the company’s small saving: no overtime for any reason. Corporate had liked the optics. Steven, my boss, had been thrilled.

Steven was the kind of person who measured success in visible strokes. He liked his suits crisply folded and his coffee black and immediate, his calendars full of meetings that wore thin and smelled of importance. When corporate decreed budget cuts Steven adopted the new policy like a soldier adopting good boots—he could look down at expense items and say: here, I am the man who saved us. He did it with an excitement that felt tasteless in its smugness. He wanted to be a hero in the numbers column and didn’t seem to mind who carried the labor.

On Friday he had sent the announcement: no overtime for any reason. He meant it. The email included a line about violations potentially leading to termination. He sent the memo to everyone. HR confirmed the policy: Halcyon would freeze extra hours. All the managers nodded along at the Monday meeting in which Steven celebrated the cut in a way that made some of us uneasy. He thought it would make him look decisive; he thought saving a little money meant he had performance on his side. He did not think about the fragility of the infrastructure his team maintained.

I had warned him. The backup system had flaky behavior since the last patch three weeks earlier. It had been my job to test that patch and to report the vulnerability. I had told him—calmly, in no uncertain terms—that the redundancy layer was degraded and that if we did not schedule emergency maintenance, we would be gambling with our largest client’s presentation. My message went into the ether of corporate: a written warning with technical details. Steven listened briefly and then, with that particular half-smile managers sometimes have when they want to sound confident in a choice, told me to handle it in normal hours. “Do it during normal hours,” he said. “No exception.”

I asked him to confirm in writing. I wanted, absurdly, for him to articulate the absurd policy. He wrote back. He sent that email out to the whole staff, to HR, to the execs: in black and white, no overtime for any reason. I flagged it in my own mailbox and felt the odd fizz of dread and a strange sense of righteousness. If things went pear-shaped I wanted it documented who’d made the call.

Monday afternoon the system began wheezing like an old man running up stairs. At three p.m. I called Steven and told him it needed two hours to fix. He asked if I could finish by five. I told him it couldn’t be done that quick. Later I sent an email documenting the exchange—just the facts, timestamps, and the line about the backup instability. HR replied automatically and politely: follow your manager’s directive; no exceptions. It felt bureaucratic and cruel in the same breath.

Tuesday the system crept toward death with the kind of slow certainty that feels apocalyptic when your spreadsheet is what keeps people’s payrolls flowing. Our monitoring lights blinked red in a way that looks obscene on a designer display. My desk filled with the oxygen of alarms. I pinged the team, cross-posted the logs, suggested a sequence of emergency moves. I told Steven the system would fail within an hour if we didn’t allocate at minimum three hours of maintenance and, more importantly, access. He replied: Denied. Handle it tomorrow. His reply was simple and absolute, because policies deliver absolutes and absolutes are convenient for men who like to look brave on the outside.

When everything died at four-thirty I felt a hollow opening in my stomach—not because I had not foreseen it, but because I had. Chaos is both humiliation and opportunity. The auditorium of the conference room filled with investors and the CEO; the lights flicked and the servers offered a high, metallic whine and then silence—like the suspense before a curtain fall.

Steven stood frozen in my doorway with sweat mapping his collar. He barked at us to get something. He stumbled. The CEO appeared with his phone pressed to his ear, the voice on the other end slightly muffled but thick with disappointed billionaires. Our biggest client was on speaker; you could hear the edges of their exasperation like an audience booing a bad joke.

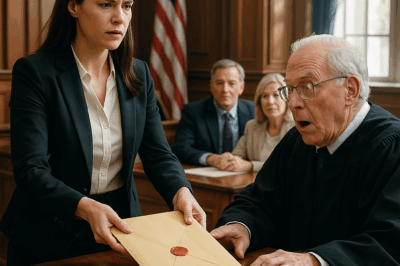

“Why is everything down?” the CEO demanded. Steven couldn’t speak. He opened and closed his mouth like a fish out of water. The room smelled like fear, coffee, and fluorescent lights. I held up my phone and showed the email chain—the Friday warning, the Monday plea, the policy memo with the “no overtime” line. I explained succinctly: I had warned him Friday and Monday. He denied overtime minutes ago. There was a crunch of paper; the legal director arrived.

The CEO said: “Override the policy. Now.” For a second it seemed like logic would overpower bureaucracy. But the legal director, a woman with a tone like flint, said: “You can’t reverse a safety policy mid-crisis. Company liability.” And there it was: the neat armor policy provides. Liability over gut-sense. The CEO sputtered. Steven started typing but stopped. He looked at me like a man drowning who had spent years building a pier with other people’s hands.

“You can’t leave,” Steven said. He physically blocked the doorway as if his arms could hold up collapse. I pointed at the clock. “Twenty-eight minutes left,” I said. The employees in the office had been tracking their personal edges for years. We have patterns that protect us—the simple rituals of leaving on time, of not being the ’emergency’ human for boss’s ego. It was five p.m. on the dot. My badge reader would sign me out. I made my move.

“You’re not authorized to work beyond policy,” I said, voice steady because my words had to be precise. The law, the handbook, the policy—they were my allies now, and I had them all documented. The legal director said, in a voice like a judge delivering stool, “It’s 5:01. If you stay, you’re there with no authorization. We will be liable.” My feet left the floor of the open-plan office and my bag swung steady at my side.

The client, on speaker, said five words that land like a blow: “We’re terminating our contract immediately.” That was the sound of consequence. Steven called me fourteen times that night. The voicemails thickened with panic; his voice vibrated like a man who had just learned his parachute was borrowed. At eleven p.m. he texted: “Can’t get into the system. Please help.” I replied with the policy you had set, boss: “See you at 9am per policy.” There was a moral awkwardness to that—an odd sadness—because in another life I would have stayed and worked until dawn and fixed it for him out of old loyalty. But his decision had been a choice to tie our hands and I had chosen his rules over his pleas.

Wednesday morning I learned the price he paid. Security told me they had found Steven in the server room at six a.m., a man hollowed out by forty-minute attempts to reverse what had already burned beyond the point of easy repair. Thirteen hours in futility and the conference room filled with the CEO, legal, HR, and two board members who all smelled like judgments. The CEO made the case: three clients lost overnight, investors sketching their exit. The legal director unfurled a stack of papers like a prosecutor: three critical system alerts ignored. Emergency maintenance denied. Overtime refused during catastrophic failure. She read it, and every word hit like a tally.

When the CEO turned to Steven he did so with an awful, clean voice. “Clear your desk,” he said. Steven sobbed like someone whose self-worth had been tied to a single brittle crown. He had built his identity out of being the neat operator of policy, and policy had eaten him. It is a peculiar thing to watch a man be defeated by the very thing he thought would save him.

The CEO then looked at me. In a strange disconnect, the same person who had fired the manager also recognized competence. I pulled out my employee handbook and put it on the conference table for everyone to see. Violating written supervisor directives results in immediate termination, the sentence read, and HR—predictable and human—nodded. They knew I had followed the rule and that I could not be blamed for being correct. The CEO said, with the frost of corporate survivalism, “Fix everything.” And in under a week, with the legal director breathing down my neck and the board confused and needing a stabilizing hand, I had Steven’s job with double the pay.

It is a strange sensation; a promotion that tastes like grief and practicality. The company needed hands who could get the systems running and who could speak the language of compliance and also the code of the machines. It needed someone who could say no and then manage the fallout of that no. It needed someone who knew the server stack by heart and remembered to document warnings cleanly. I was that person. But my salary raise did not erase the unease: Halcyon lost clients, investors rebuked us, people in the office left with the feeling of the house being rearranged.

That first week as acting director was a blur. I came in early, left late (but only within the new authorized windows), and built patches and temporary bridges. I fired three vendors with outdated support contracts, reorganized on-call rosters, and updated the emergency operating procedures to ensure that “no overtime” was never again sent as a directive without a provision for emergencies. I mandated a clause that said “overtime to be authorized by operational lead in lifecycle failures”—a safety valve, so that no future Steven could blithely broadcast policy and then watch the company drone into a disaster. You can see how indignation and pragmatism mix: my ethics had a shade of practicality now.

But the deeper story was social: the culture accepted a man’s pundits that made policy into an image. People applauded budget-saving in meetings because in so doing they could say they were responsible. But the invisible labor that made those saving possible—engineers willing to take the overtime—were assumed to be always there, willing to accept the pressure for free. Policy had become a moral theater that sanctified the savings while mortgaging stability. I fixed codes that night and rewrote behavioral terms for the company the next morning. You pivot not just code but norms.

As the dust settled a week later, the damage remained. The client we lost was replaced by a newer one with different tolerances. We rewired contracts in ways that made the company more resilient but also less green with naïveté. Steven’s parting words from HR were not violent or cruel—he was escorted politely, like a man leaving a private jet. I found myself in his office, the view from the tenth floor suddenly looking different in the afternoon sun. His resignation felt like a body left at the scene; policy had eaten him.

Walking through the office in the days after, I noticed the glances—some calculating admiration, some vacant shock. People were adjusting to the idea that the policy that had been celebrated was in truth a brittle thing. Some of my colleagues were relieved that someone had the courage to call trouble; others whispered that the system had been doomed because someone dared to be a litigious observer. Culture cracks slowly, but when it snaps it renders small truth monuments of memory.

When you inherit a role after a public fall you do not get a parade. You get the time-on-the-job and the responsibility. And you also collect the obligations of the person who got fired. I was now responsible for steering a fragile vessel in choppy seas. My inbox filled with requests; investors wanted assurances; clients needed guarantees. I built the fixes and implemented a resilience plan with redundancies that meant buying into slightly higher operational costs. It was boring in the way that real, good work is boring: tedious, slow, and sustainable.

And through all of this, there was a lesson that lasted beyond salary numbers and boardroom memos. The “no overtime” rule, born of a budget spreadsheet, had been a short-term performance indicator. It had been wielded like a blade by Steven to show off his fiscal virtue. But the blade cut where policy had no skin—people’s trust, the integrity of our commitments. He had forgotten that the systems we are stewards of are not just machines but relationships. Uptime is not simply continuity of code; it is the trust placed in us by those who rely on the systems our company runs.

That is the end of one story: a manager makes a rule, an engineer documents a future calamity, disaster follows, and the company reshuffles. The ending is not cinematic. It is an accounting adjustment with human consequences. People lost jobs and those who stayed learned rules that will hopefully protect them the next time an executive seeks heroism through austerity.

Part Two

If Part One is a theater of decisions and immediate consequences, Part Two is the long hour after the curtain falls: the way culture rearranges itself, the ethics of leadership reconsidered, and the personal cost of being right in a place that values being loud over being accurate.

In the days and months following the crash, we rebuilt not just architectures but policies. The executive briefing room that had been carved into theater became a lab. We rewrote the emergency response binder until it felt like a living document, one that recognized the human edge and the engineering needs. The new policy included provisions for emergency override by the operations lead with an audit trail and a quick escalation process. There were also personal changes: Sunday evening shutdowns were restructured to distribute the burden, and we set budgets that accounted for controlled, authorized overtime.

The board learned the most practical lesson: cheap is seldom cheaper in the long run. We embraced the terrible arithmetic that sometimes the unit cost of resilience is front-loaded. You cannot patch culture with spreadsheets alone. You patch it with the steady insistence on people’s boundaries and legal specifications that do not allow for panic-based heroics. And if a leader wants to cut costs, they must also be prepared to accept the transparency of their choices when things go wrong. Steven was not the only person who made bad choices that quarter; the temptation to look good on a spreadsheet is tempting for many.

My promotion came with an office plant that someone had fashioned into a ritual gift and a raised line in my paycheck. It also carried a weight: people assumed I had been the one who enforced the old policy because I knew it. They did not entirely trust me; suspicion grew as the company narrative ratcheted between praise and blame. There was an unspoken question I had to answer every day: had I followed the rule because it was fair, or because it was the safest political position? The answer was messy; it was a mixture of law and personal ethics. I had chosen to follow procedure because that was my protection and because it was a message: policies that do not include rescue clauses are weapons.

One of the first things I did was schedule town-hall meetings. We gathered in the auditorium with coffee and stale chairs and I explained the new emergency clause. I told a carefully honed story: about the warning emails and the denied overtime, about how policies without a safety valve are brittle and about how we would now be transparent. People who had wanted immediate change applauded; others murmured. But change does not happen from speeches alone. It is cements into daily practice: leading by showing how you behave under pressure.

My team was small and burned out, and the loss of three clients meant budgets were tight. Some people left. They found other jobs, sometimes with better pay, sometimes with better alignment. I worked to keep morale: we did lunches, we brought in training—real budgeted training—and we celebrated the small wins of stability. We implemented rotating on-call rosters that were fairly compensated. We paid overtime that was pre-approved and logged. We established an independent engineering council that could petition for emergency funds when infrastructure risk metrics crossed a threshold. The bureaucracy that once had been Steven’s toy became, under my stewardship, a tool that preserved people and systems.

Steven’s fate was human and curt. He faded into the world of managers who had one big failure and then had to reconfigure their careers. Some of us wondered if he would ever find a place where his policy zeal was compatible with real systems. When his successor left for a small startup a year later, I saw a man who looked chastened and maybe, privately, wiser. Maybe he had learned that rule-making is not a theatre trick; it has mortal consequences.

But let us be honest: I did enjoy a certain satisfaction. When a leader crafts a rule that makes him look good in the short term but leaves others to do the heavy lifting, and then that rule fractures under a crisis, it is a bitter thing to watch. When you have been the person who warned, when you have documented your concerns, and when your integrity is in a memo with timestamps, there is both vindication and emptiness in being right. It does not repair the clients we lost or the reputation we hemorrhaged for months. But it does mean the next time a manager thinks to sculpt policy to their own vanity, there is a ledger to counter the charm speech.

Two themes braided themselves together on the back end of the storm: responsibility and humility. Responsibility because you cannot claim the virtues of thrift without assuming the consequences of the risks your thrift imposes on your people and on your product. Humility because a leader who wants to save a buck must wake each morning with the awareness that his decisions bend other people’s lives. It is better morality to speak plainly about costs than to dress them in policy and call them morals.

We also learned practical things about infrastructure. We built hot-spare clusters in a way that minimized manual interventions. We bought more than just talent; we invested in vendor support contracts that ensured someone on the outside had the obligation to pick up the phone at two in the morning. We implemented synthetic transaction monitoring: tiny web clicks that simulate user flows and catch degradation before investors were in the same cathedral of defeat. These were technical changes that cost money. But once they were in place, they made return visits to panic rarer.

The cultural shift, however, took longer. Policy shift is a good beginning; culture is a slow re-sculpting of human behavior and expectation. I spent months walking the floors, talking to people one-on-one—engineers, product managers, and the new hire who had just started and who looked at the whole debacle like a nervous bird. I listened to their fears and worries and fed them back into the system that would now make sure policy had fail-safes in place. You fix code, you fix human processes. Both are engineering.

My personal ethics also took a beating and a reshaping. I had once been someone who saw myself as indispensable—another version of the heroic worker who will save the day for free. There is a subtle moral hazard in that identity. It teaches other people that your labor is inexhaustible and that your limits are invisible. When you insist on your boundaries, people call you petty. When you abandon them, the world calls you reliable. The trick, as I learned, is to institutionalize the boundary: encode it in policy that values effort and protects weekend time, then make sure that policy has an emergency clause that is itself governed by a clear audit trail.

My promotion was worth it in the bare sense of salary and the authority to change organizational habits. It also left me with the obligation to keep up with the moral tone. A leader is measured not simply on outcomes but on how those outcomes were achieved. If you built uptime by burning people at the stake, it’s not a win. If you built uptime by building capacity and respect, then you have created durable resilience.

At quarterly reviews a year later our metrics had stabilized. Investors returned with guarded optimism, and we had a contract with a huge client that required the very failover models I had championed. The legal pushback had done us a favor: it forced clarity. The company replaced a short-term, vanity-focused policy with a principle-based approach: clarity in risk metrics, a humane fallback clause, and a compensation model that rewarded availability and did not exploit generosity.

If there is a poetic end, it is a quiet one. At the anniversary of the crash the company held a small ceremony. No balloons, no fanfare—just a brief meeting in which the CEO acknowledged the failures and the people who had helped fix them. He said, plainly: “We all learned a hard lesson. Thank you.” In the crowd, some employees clapped and some did not. People who had seen the policy collapse and then rebuilt their lives inside the rescue we had implemented understood both the cost and the dignity of stability.

Some months later Steven reached out in a short, awkward email. He asked if we could get coffee. He did not ask to apologize directly; he did not try to weasel back in. We met once. He looked thinner, older in a way that had nothing to do with age. He said the phrase no manager wants to say: “I miscalculated.” He told me he had become in love with the optics of austerity and that he had lost sight of the human labor that made the optics possible. I told him that policy is sacred only when it is humane.

He left the coffee shop an improved man, not in the moral perfection sense but in the sense that a person who’s been humbled can sometimes make better choices moving forward. We both laughed at the absurdity of how many companies still let spreadsheets count as wisdom. I told him he’d make a fine consultant somewhere in the future if he could keep his ego in check. That was not mean; it was practical.

The last scene I will tell is small: one late Friday I stayed at my desk long enough to watch the city lights ripple out over the streets. The servers hummed with a gentle, ordinary sound like someone breathing in sleep. My phone buzzed and it was a simple message from a junior engineer on my team. “We fixed the alert thresholds. Night looks quiet.” There was a small pride in that message that was not mine alone; it belonged to a team that learned by the school of fire and by the hard lessons of a manager’s vanity.

My boss had made a rule he instantly regretted. It cost him his job. It cost the company money. It taught us a lesson about the perils of policy without heart. But in the aftermath, we built a better system: not just a more resilient cluster, but a culture that recognized that policies are about people as much as they are about spreadsheets. We rewrote our rules with more care.

If you ask me whether I am glad Steven is gone, my answer would be nuanced. I am glad because the company needed to survive. I am not glad because I watched a human being fall. Leadership is stewardship and stewarding requires humility. The story ends not with revenge or gloating, but with the slow, patient rebuilding of something that will hopefully withstand the next storm. The house remains standing because people decided to build better, not because anyone decided to punish or to celebrate. That is a kind of small redemption.

And finally, a small, personal addendum: I still pack my bag at five. Not out of spite, but out of habit. Boundaries are not political acts; they are a structure for life. We are not machines. A rule without a safety valve is simply a brittle hope. I learned that. The company learned that. Perhaps the hardest lesson remains the most human: be brave enough to look at both your costs and your people, and be humble enough to change your mind when you are wrong.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

MY SISTER DUMPED HER BABY ON MY DOORSTEP THEN DISAPPEARED MY PARENTS SAID, “SHE’S YOUR BURDEN… CH2

My sister dumped her baby on my doorstep then disappeared; my parents said, “She’s your burden now.” Ten years later,…

AFTER MY FATHER-IN-LAW’S FUNERAL, MY UNEMPLOYED HUSBAND INHERITED $210 MILLION-THEN LEFT ME WITH… CH2

After my father-in-law’s funeral, my unemployed husband inherited $210 million—then left me with a smug grin. “You’re useless now,” he…

My parents protected my nephew who broke my son’s ribs and refused to call for help. CH2

My parents protected my nephew who broke my son’s ribs and refused to call for help. Part One On…

A week before her birthday, my daughter told me: “The greatest gift would be if you just died.” CH2

A week before her birthday, my daughter told me: “The greatest gift would be if you just died.” So I…

FOR YEARS MY FAMILY TREATED ME LIKE DIRT AND AT MY SISTER’S DREAM WEDDING THEY HUMI…. CH2

For years my family treated me like dirt and at my sister’s dream wedding they humiliated me one last time…

My Sister Dumped Her Kids On Me For The 5th Weekend In A Row. When I Told Her I’m Not Their Built-In. CH2

My Sister Dumped Her Kids On Me For The 5th Weekend In A Row. When I Told Her I’m Not…

End of content

No more pages to load