My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built…

Part One

The subject line was sterile as a hospital corridor: Change in Employment Status.

The body was worse.

Clean out your desk by close of business today. Human Resources will process your exit documents. We need employees who make their work a priority.

I read it twice, three times, until the words blurred and sharpened again like a cruel magic trick. My monitor glowed in the quiet of the Seattle dawn—most of Peak Valley Shipping’s staff wouldn’t arrive for another forty minutes. I had come early to widen the narrow ledge time had left me after three days away. Three days to bury my mother, the person who’d taught me which way to hold a compass when storms pretended they were directions.

The email had been sent by Greg Turner. The same Greg who had signed the bereavement-leave form with a sympathetic nod and a perfunctory take whatever time you need. I stared at his signature block, the faux-friendly —G before the full name and title as if the dash could soften a blade.

I didn’t cry. It wasn’t that kind of morning.

I took out my phone, photographed the email, forwarded it to my personal account, and powered the computer down. Then I began the small, necessary ritual of endings: framed photo off the shelf (my team, wind-tangled and laughing at last summer’s retreat), the succulent from last Christmas carefully wrapped in the Monday edition of the Seattle Times, a stack of thank-you notes from people I’d mentored clipped together with the binder the color of moss after rain.

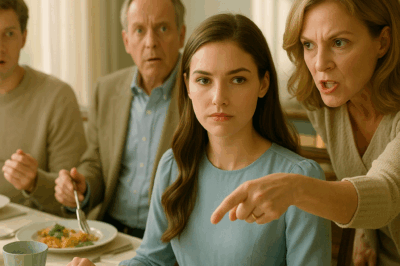

“S—sorry.” Samantha from accounting skidded to a stop. She glanced at the box, at my face, back to the box. “Morgan, what…?”

“I’ve been terminated,” I said, the words coming out neat, like I’d spent the night ironing them.

“What? Why?” Her outrage was so genuine it hurt.

“Apparently,” I said, “attending my mother’s funeral signaled insufficient commitment.”

Other faces gathered as the floor filled—Eric’s smile collapsing on impact, Rebecca’s hand flying to her mouth, Nathan’s jaw grinding so hard I heard it in my teeth. Beyond them: Chris, Angela, Monica, Sophia, and Jack, each wearing a version of disbelief that had graduated into anger.

“None of this makes sense,” Eric said. “The West View merger—your numbers—eighteen percent growth this quarter is—”

“—not enough to withstand poor optics,” I finished softly, and bent the flaps of the cardboard box inward. “At least for Greg.”

A hush spread out like water under a door. Then the voice that vacuumed air out of rooms: “I need everyone back at their workstations.”

We turned. Greg Turner stood with arms crossed, jaw shaved too close for the expression he wore. “We have deadlines,” he added, as if that were a moral stance.

No one moved.

He waited, then dropped his tone into the register bosses use when they practice power: “Right. Now.”

They drifted back, but slowly enough to be called loyalty.

Greg approached, lowering his voice. “This could’ve been handled discreetly if you’d packed up at end of day.”

I looked at him and thought of my mother standing in the Cascade, water pushing around her legs. The river moves, but the stones remain. “Like the discretion you used firing me by email?” I asked.

A thin crack opened in his face and closed. “Business requirements change quickly. Peak Valley needs employees who understand that priorities shift.” He paused, reached for sympathy, found nothing in his pocket. “Your mother’s passing was unfortunate, but—”

“Don’t finish that sentence,” I said, in the tone you use when stopping a child’s hand from the stove.

Human Resources was a room trying to smell like lavender over antiseptic. Natalie Fam shuffled papers that had been printed too recently to be kind. She’d only been with Peak Valley six months; empathy still clung to her like a new scent.

“I’m… sorry,” she said, and I believed her. “And I am very sorry about your mother.”

“Thank you.” I scanned the separation packet. Two weeks’ severance. A non-disparagement clause that imagined I had time to narrate their sins for free. A non-compete prohibiting me from working for any direct competitor within 300 miles for six months.

“Do you know… why?” she asked, careful. “It seems… abrupt.”

I slid my phone across the desk. She read the email, inhaled sharply, and set it down like something that might break or explode.

“I need to check something with legal.” She vanished down the hall and came back twenty minutes later with the practiced neutrality HR uses when law beats conscience. “Washington’s at-will,” she said softly. “If you chose to pursue…”

“I won’t,” I said. “But thank you.”

Outside, September was surprising me with gentleness. I loaded the box into my trunk and sat with both hands on the steering wheel without starting the car. Then my phone filled with the warm weight of my team—pings that sounded like people.

Eric: This is wrong. What can we do?

Rebecca: Where are you? We’ll come.

Nathan: He’s a coward. The team is furious.

More followed. I answered none of them right away, but I let each one land where grief had been and feel a little like shelter.

I didn’t call Greg. I didn’t stalk into Richard Bennett’s office to demand due process from the district manager who should’ve been looped in and, evidently, had not. I did call someone else.

“Julia,” I said when the line clicked live. “It’s Morgan.”

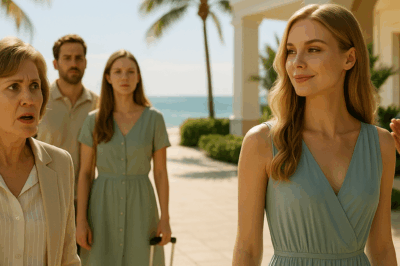

“I heard,” said Julia Blackwell, CEO of Summit Global Logistics and the only person who’d ever made me consider leaving Peak Valley while I still loved my job. “Come in.”

Summit’s office was all light and lungs: glass, breathing plants, the hum of people choosing ideas over fear. Julia greeted me with a handshake that didn’t need to prove anything and eyes that saw too much to require spectacle.

“Show me,” she said.

I slid the phone across the table and watched her face darken.

“Bereavement leave is not a performance problem,” she said. “It’s a policy so humans don’t break.”

“I don’t want to sue,” I told her when she offered before I asked. “I want to move.”

“Then move here.” She smiled. “Pacific Northwest Operations needs a director.”

The word director slid into my bones like iron. “My non-compete,” I said out loud to both of us, so we could push it into the air and see what it really looked like.

“Our legal team has read it,” Julia said, and her voice did the thing mine had done with Greg’s. “Too broad, likely unenforceable. Especially in the context of wrongful termination. We’ll cover everything.”

“Give me the weekend,” I said.

“Take the weekend,” she said, already trusting I belonged. That mattered more than I expected.

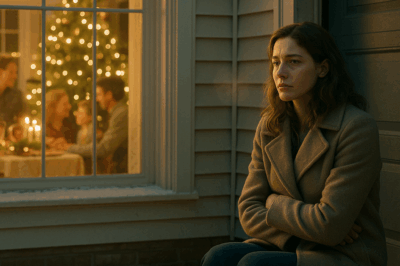

We didn’t cry at Shoreline Brewing that night. We laughed and swore and built miniature battle maps out of napkins. Rebecca cried because she cries at justice as quickly as she cries at cruelty, and both look the same if you only see the water.

“Greg’s called an emergency Saturday meeting,” Eric said, grimacing at his phone. “No one can find your Thompson files. They thought they were called ‘Thompson Renewal’ or something equally imaginative.”

“They’re under TMT-Q4/Continuity,” I admitted, “nested under Accounts with Nosy Auditors.”

Rebecca snorted into her glass. “You were always extra.”

“My mother taught me to hide candy in the coat closet,” I said, and we all toasted a woman none of them had met.

On Saturday, I sat in Marcus Diaz’s office, the lawyer recommended by a friend whose heart never covered her math. He examined the non-compete like an insect under glass.

“This reads like it was drafted by a frightened octopus,” he said. “Six months, 300 miles. In Washington, courts are increasingly hostile to restraints this broad, particularly when the employee was terminated without cause. And firing someone after approving bereavement leave?” He bent the paper, then flattened it. “If you wanted to litigate, you’d win. If you don’t, you’ll still probably be fine.”

“Fine is enough,” I said.

On Sunday, the Cascade River remembered me. I stood in the same bend of water where my mother translated currents into sermons. The river hissed and whispered and roared in all the right places, the long sentence of it intact: Move. And be the thing that does not.

On Monday morning, I called Julia. “Yes,” I said, “with one condition. I build my own team.”

“Done,” she said. “Whoever you want.”

By Tuesday I had signed. By Wednesday, seven applications landed in Summit’s ATS at once—Eric, Rebecca, Nathan, Chris, Angela, Monica, and Jack—and I laughed out loud in a way that felt like forgiveness. On Thursday, Summit HR scheduled interviews. On Friday, Summit extended offers.

On Monday of the following week, Richard Bennett called. His voice was aspirin dissolved in water: bitter and already late.

“I just received seven resignations,” he said without preamble. “Your former team. Effective immediately.”

“Richard,” I said, keeping mercy inside the boundaries of truth. “I don’t work for you.”

“They’re all going to Summit,” he pushed. “Where you’ve just joined as Division Director. You see why this looks—”

“Like you mishandled a termination and a culture and a business?” I said mildly. “Yes.”

“I am prepared to offer you your role back with a ten percent increase,” he said quickly. “An apology—formal—public, if you want. Just tell me what it takes.”

“It takes a time machine,” I said. “Back to the Monday you said nothing while your subordinate typed ‘clean out your desk’ into a bereavement week.”

“Your non-compete,” he tried, reaching for policy like a life-jacket.

“Have your counsel call Marcus Diaz,” I said. “He’ll enjoy the conversation.”

By Wednesday, Natalie from HR sent me an email that read like a bruise: Greg Turner is on administrative leave pending investigation; the board is—concerned. I stared at the sentence and thought: Concern arrives after the body. I didn’t reply.

The Thompson account moved to Summit with us. The Rodriguez account followed a month later. We didn’t crow on LinkedIn; we delivered trucks on time. We didn’t leak memos; we picked up calls. The clients understood what leadership actually looks like: the feeling when you say a thing once and the right person writes it down and it turns into a truck in the right dock at the right moment.

Julia gave me a budget and autonomy and the kind of feedback that assumed I wanted to be better more than I wanted to be praised. I built the team culture I’d craved for years. At the top of our Kanban board, written in purple dry-erase: We are humans, not throughput. Underneath it, in smaller handwriting no one ever erased: Grief is not an “inconvenience.”

When Summit’s first quarterly numbers came in after our division’s fully staffed reconstitution, I stood in front of a wall of glass and told a story with numbers for sentences: thirty percent growth, twenty-two percent efficiency gain, four major acquisitions, three from Peak Valley’s old top-ten. Julia’s smile was a lighthouse behind me.

“Exceptional,” she said. “Not only the result—the way you did it.”

“Stones,” I said, feeling my mother’s hands pull damp hair off my forehead in memory. “River.”

We cut a cake with Independence Day iced on it in corporate-blue frosting. We ate it laughing, the way people do when they love the people they built the win with. The succulent Natalie had packed for me sat on my windowsill, plumper than when it survived Peak Valley. It was growing in a place with better light.

A few months later, I took a lunch with Richard after he’d resigned from Peak Valley to consult on culture for companies who had finally noticed the math on attrition, grief, and productivity. He ordered a salad he didn’t eat, then leaned across the table with a face that had learned humility the expensive way.

“Was it worth it?” he asked. He meant: Was walking silent into a new life better than staying to fight the old one.

I thought of Rebecca’s wicked-smart revamp of client communications, of Eric running a parallel division like he was born for it, of Nathan’s quiet way of solving impossible routing puzzles, of Angela finally being paid in salary and thank-yous for the emotional labor she’d shouldered under Greg, of Monica and Sophia and Jack smiling in meetings without watching the door for danger. I thought of the policy binder we wrote that didn’t hide bereavement under “other”—it had its own page, its own language, its own defiance.

“Yes,” I said simply. “Look around.”

He nodded. “We lost the company,” he said without self-pity, more like a weather report. “Northern Transit barely paid pennies on the dollar. Greg… no one will touch him. A story like yours gets told.”

I didn’t run a victory lap. I took a walk. To the river.

My mother had taught me all the leadership I’d ever really need on weekends in waders. Stand where you can see the current. Put your feet where the stones know how to hold. Don’t fight the water; it will always, always be more patient than you.

A year to the day after Greg’s email, Julia announced my promotion to executive vice president of operations for the Northwest region. My team stood in the back of the room and whooped and I did the thing bosses are supposed to do and pointed at them and said their names because if people don’t hear their names in rooms where they did the work, they stop coming into those rooms.

That afternoon a small, battered box arrived at my office with no return address. Inside: my old succulent, now thriving, and a note in Natalie’s handwriting. Rescued this from your desk before Peak Valley shut the lights. Thought it belonged in a place where light isn’t rationed. I put it in the sun. I sent her a thank-you that said more than it wrote.

There is a particular kind of quiet you earn only after choosing to be a stone when a river tells you you’re a twig. It doesn’t sound like triumph. It sounds like breathing.

I drove to the Cascade and waded into the water until the cold stung my knees. The river said nothing wise. It didn’t owe me wisdom. It flowed past, indifferent to boardrooms and emails and men who thought sympathy had a timeclock. It knew only movement and the fact of stones.

“Thanks,” I said anyway, to no one and everything. “For teaching me not to be moved by people who confuse cruelty with standards.”

A pair of mergansers rode the current like little executives in the right kind of meeting. I laughed, thinking how my mother would’ve narrated the ducks and the choice I’d made and the cake we’d eaten. Then I went home, where my team’s names were on the wall under Hires, the bereavement policy had its own page in the handbook, and a plant that survived a company looked out over a city that finally felt like it belonged to the people who’d built it.

Part Two

Snow arrived early that year, a quiet handwriting across the city that made everything look like a clean page. Inside Summit, the heaters hummed and the coffee machines worked overtime, and our whiteboards bloomed with new projects written in four different people’s markers.

On the wall of our floor, next to the floor-to-ceiling windows, we pinned a poster that wasn’t there the day Greg fired me: Compassion is a competency. I wrote most of the policy that sat behind that sentence, but a dozen hands made it better. We didn’t bury it inside the handbook—our bereavement framework was a living document on the intranet, one click from the homepage, with three big buttons.

I need leave.

I’m supporting a grieving teammate.

I’m a manager; my employee is grieving.

Clicking any of them didn’t take you to legal clauses. It took you to plain language, checklists, and names. We named things because grief hates euphemism.

Two weeks after we published it, Jasmine from inbound operations lost her grandfather—the man who raised her while both her parents worked night shifts. She came into my office with eyes like someone had carefully emptied them. “I’m supposed to supervise a Saturday unload,” she said, apology already braced in her shoulders. “For the clinic routers. I can move the service to Monday but I—”

“Stop.” I slid the laminated card across my desk like a life preserver. We made this for you before we knew you. “Two weeks paid. Your team lead is already rescheduling. Do you need additional travel funds? We have them.”

Her face broke in a way that made my own waterline rise. “I’ve worked since I was sixteen,” she whispered. “No one’s ever… named it.”

She pressed her fingers to the card like a fragile thing that could still be useful, like a river stone.

Grief was one part of the story. The other part was bread-and-butter operations: trucks, docks, deadlines, and a winter storm that decided to walk into the Pacific Northwest like it owned the place.

On a Wednesday night in January, weather radar looked like a curtain closing. Air traffic grounded. Highways flashing chain requirements. The phone on my desk began its steady double-buzz—every quarter hour another distribution center calling with closures. On the big map, ten little red dots went dark in an hour. Hospitals still needed IV pumps. A tribal community we served needed bottled water after pipes burst. A local food bank had two days’ worth left.

“Night ops?” Julia said in my doorway, already pulling on a coat she never wore indoors. Her hair was wet from running to our floor. “We’ll need a control room.”

“Already building it,” Eric said, appearing behind her with a rolling whiteboard and the energy of three espressos. He had a cat hair stuck to his beanie and a grin that said: We get to do the thing.

We turned the big conference room into a wartime bunker. Nathan fed us weather models and road closures like a chess puzzle. Rebecca worked the phones with clients, getting the real need from the polished script: What will actually break if your shipment arrives Friday instead of Thursday? This return-to-service window says 4 hours—what is your 1-hour version? We turned UPS stores and grocery freezers into temporary depots. Angela called the Tribe’s emergency manager and found out the last-mile route by texting a cousin-of-a-cousin who knew which forest service road the plows actually prioritize. We routed an ambulance’s pallets onto three snowmobiles. We fed drivers hot soup and told them to sleep on cots the facilities team pulled out from the earthquake kits. No one asked permission to do the right thing. They just ran a checklist they’d helped write when the sky was blue.

At three a.m., a voice memo from the ER nurse on the Yakama reservation pinged my phone. You could hear the relief in the clatter behind her. “We got the pumps,” she said. “You were the only ones who called back. Tell your drivers we’ll send frybread next time.” She laughed. It sounded like moonlight on ice.

When I finally fell into my bed at dawn that Friday, the city was silent under the snow, and my phone had the kind of buzzes I don’t love: reporters. Rebecca begged me to go on NPR, then sighed and did it herself, talking about “robust partnerships” and “redundancy and care.” She left my name out. I loved her for that.

The next week, an email from a group of hospital administrators hit my inbox. Your folks saved lives. They addressed it to me, but I forwarded it to every driver, temp, dispatcher, and janitor who let us turn the cafeteria into a sleeping pad factory: You did. In the column where we kept performance metrics, we added a line: Lives touched. It wasn’t precise. It was true.

Peak Valley’s CEO, the interim one Northern Transit installed, sent a cheerless press release about unprecedented storm conditions and valued partners. It sounded as warm as ice. The thing about a storm is that it doesn’t care whose logo is on the van. It cares who shows up.

In February, I stood on a stage in a hotel ballroom at a logistics conference listening to a panel about “Resilience.” Three men in matching blazers said “synergy” and “AI” and “disruption” like they were ordering from a menu. When the moderator called me up, she whispered, “We could use a different word.”

“Stones,” I said. She blinked, then smiled and handed me the mic.

I didn’t talk about throughput. I told them about Jasmine’s card and an ambulance on a snowmobile and a frybread promise. I told them my mother taught me to stand where the current can be seen and to let the things that need to move, move. I told them culture is logistics for humans. The room was quiet. People do quiet when they suspect they’ve been facing the right direction with the wrong map.

Afterward, hands. Cards. Someone from Northern Transit shook mine, said he liked the stones metaphor, asked how to do “compassion at scale” without losing efficiency. I asked him why they assumed they were separate. He blinked, then nodded like he’d been hoping someone would say it out loud.

Greg was in the back of the room. I’d heard he’d started a boutique “performance advisory” shop that had three clients and an unpaid invoice. He looked smaller without a department behind him. He waited until most people had left. Then he walked up and said my name like it tasted strange.

“I wanted to apologize,” he said. No preamble. His mouth was careful, as if emotions were a language he didn’t speak regularly.

“For the email?” I asked gently, putting my hands in my coat pockets to keep from being unkind.

“For everything,” he said, surprising me. “I thought being hard would make me… respected. You built what I pretended I was building.”

I waited. A river stone doesn’t fill silences; it just lets the water define itself around it.

“I can’t get work,” he said quietly. “It turns out culture follows you like smoke.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I meant it in the human way. Not because I wanted what he wanted, but because shame is a poor teacher and too many people study with it.

He looked at the floor. “I know I’m not owed anything,” he said. “If you hear of… entry-level consulting gigs—small—policy audits—I could—”

“I’ll pass on your resume,” I said. It was the exact middle between vengeance and absolution. “And… Greg?”

He looked up.

“If you want to consult on culture, go volunteer first. Not for the optics. For the muscles. Work a food bank line when a storm closes roads. Staff the bereavement table at a hospital. Learn what grief looks like in fluorescent light. That’s what culture feels like at scale.”

He nodded. There was relief in it. The kind you see when someone is handed a map and a pair of shoes.

By spring, Summit asked me to keynote a company-wide town hall about our “People First” framework. I don’t like the way phrases turn into posters. But I stood at the mic and told the truth anyway: that policy is a love letter you write in advance to the worst day of someone’s life. That a meeting with your boss at the bottom of a staircase should never make you regret attending your parent’s funeral. That we were going to measure our quarterly results by revenue and retention and return home rates—the percentage of people who come back from hard things and say: “I was allowed to be human and I still wanted to do the work.”

After the Q&A, a woman I didn’t know came up crying in a way you can’t script. “I lost my wife last year,” she said. “I took two days because I was afraid. If this had existed—” She stopped and swallowed the end of the sentence like a pill that tasted bitter. “Thank you.”

I wrote my mother’s name in the corner of the whiteboard that afternoon and underlined it once. No one erased it. They started adding their own. By the end of the week, the right-hand corner of the board looked like a small town cemetery. It wasn’t morbid. It was inventory: these are the people who built us that you never saw.

In June, I testified before a state labor committee considering a bereavement leave bill. I’d avoided “platforms” when I left Peak Valley because the internet makes everything loud and untrue, but this felt like the right room.

The hearing room smelled like coffee and fear. Lawmakers in suits looked at me the way people look at a map of a place they’ve never walked.

“If you pass this bill,” I said, “some companies will say they can’t afford to give people time to bury their dead. Ask them how much it costs to recruit replacements for the people who leave because their grief wasn’t allowed to be human. Ask them how many productivity graphs they filed that never measured the moment a driver decided to take his talent to a place that made space for his father’s voice to stop.”

An older representative with a tired tie asked me whether small-medium businesses could handle another mandate. “Mandates feel like walls when your culture already aligns with the intention,” I said. “If you build your workplace like a force field against humanity, every humane law will feel like a punishment.”

Afterward, a young legislative aide caught me in the hall. “My mother died last month,” she said in a voice that sounded like a place where wind lives. “I still came in because I’m new. I thought I had something to prove.”

“You did,” I said. “But it wasn’t that.”

We stood together on the granite steps in our coats until the rain turned to mist.

In August, on a day when the river looked bored with summer, Julia called me into her office to show me the draft of a press release I’d been putting off for months. “Summit releases open-source CARE kit: Compassionate and Resilient Employment.” The toolkit included our bereavement framework, manager scripts, leave request templates, calendars for how to re-onboard people returning from loss, and a one-page that said: How to talk to someone whose parent just died. People had contributed lines like, “Don’t say at least.” “Don’t compare griefs.” “Say the name of the person who died.” “Tell them the one thing they did last year that mattered in a way they maybe didn’t know you noticed.”

We licensed it Creative Commons and pushed it into the world. The downloads map lit up like a holiday parade. Competitors used it. A small bakery used it. A hospital in Yakima used it. The HR head at a startup DM’d me to say their CEO cried in the all-hands when he read the line about loving employees like a verb.

People asked Summit to present at HR conferences. We sent Jasmine.

In October, a tidy, unmarked envelope arrived at my office with a return address that read only Cascade County, Clerk of Court. Inside was a copy of a settlement from Peak Valley: a formal acknowledgment of wrongful termination and a check that would buy a car I didn’t need. I deposited it and used it to seed a fund for drivers who needed quick cash when a transmission died. We named it The Stone Fund. We didn’t have a glossy application. People emailed a dispatcher and said “my car” and we said “go to Brian in Fleet; he’ll hand you the card.”

A week later, a thick cream envelope with no return address landed on my desk. Inside, a handwritten note in a compact, elegant hand:

Morgan—

I attended your town hall with my nephew who works for you. I wanted to tell you that when my wife died, I sent two of my associates home and fired a third. It wasn’t grief; it was panic. We all pay for our ignorance in ways we didn’t budget for.

—G. Turner

He enclosed a check made out to The Stone Fund with a sum that would replace ten transmissions. I walked it to Finance myself, breathed out something I couldn’t name, and then went and stood by the window until the river in my mind was louder than the memory of his email.

In November, the logistics association named me Operator of the Year in a banquet that felt like a wedding where strangers hugged you for the vows you wrote at work. Jerry from Yakima brought the ER nurse and she cried when I mentioned frybread from a stage in an outfit my mother would have loved because it didn’t pretend not to be clothes.

I walked up to the podium and looked out over a room of people who move refrigerators and vaccines and kindness and I thought about my mother’s fingers at my temple rinsing river water out of my hair. When I spoke, the words didn’t feel like mine as much as inherited:

“I’ve been called strategic and ruthless and, this year, compassionate. None of these are wrong. But the word I want for us is stewards. We steward freight and time and each other. We do not control the river. We decide, every day, how we stand in it. Thank you for teaching me that leadership is logistics for souls.”

Julia put her arm around me when I sat down and whispered, “Your mother is probably making fun of your shoes.”

“She would have said they look like someone named them,” I whispered back.

On the anniversary of my mother’s death, we didn’t hold a vigil or a speech or a press conference. We held a potluck in the break room with a theme: Recipes our mothers knew by heart. There was a table for people with complicated mother stories and a card that said that was allowed. People pinned photos to a cork board and wrote names on Post-its so the living would know the dead. The pie Angela brought tasted like someone had told you the weather would be good for the next three days. Nathan, who never tells long stories, told three in a row about his mother measuring flour with the same cup she used for rice. We sent plates home with a driver who couldn’t stay because a road was washboarded into dust.

That night I drove east with a trout pole in the trunk, the city behind me and a weather report that promised clear water. The river didn’t look decorative or narratively cooperative. It looked like Earth moving, as it always had, as it will long after we build and sell and restructure and write policies and appendices.

I stood in water that remembered my lungs and I cast badly twice and well once. The line lifted, suspended between motion and wait, and I thought of the email that could have broken me open and poured me into a jobless winter and how instead it taught me muscles I didn’t know I had. I thought of how revenge is a small cup and you drink it fast and it leaves you thirsty. Building is a river, and if you’re lucky, it says your name back occasionally in the shape it takes around your ankles.

Somewhere back in the city, a team I loved was closing laptops and heading home to people whose names I could sometimes say without looking at the org chart. In a hospital, a nurse I didn’t know was removing a plastic bag from a pump we’d delivered on a snowmobile. In a rural pantry, a cultural liaison with last night’s long braids was counting how many boxes had made it up the mountain on time. In a break room at Summit’s Yakima depot, Jasmine had just taped a new laminated card to the corkboard: You can be gone and belong.

I reeled in, wiped wet fingertips on my jeans, and let the river do its work.

END!

News

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped “She’s My Boss”… ch2

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped, “She’s My Boss”… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load