My boss fired me for his nephew. He didn’t know I was the anonymous investor who owned a controlling share of the company.

Part One

The night they toasted Kevin with my patent in his hands, I learned what it feels like to stand on a sinkhole that smiles back.

Streamers. A string quartet hired on too-short notice. A balloon arch in Innovate Dynamics’ colors framing a stage we usually used for all-hands announcements. Mr. Harrison had a microphone in one hand and a highball glass in the other, and the room glowed with the soft light that hides fingerprints even when it can’t hide intent.

“To fresh blood,” he boomed. “To bold vision.” He turned a fraction toward me, just enough to include me in the light while excluding me from its warmth. “To the kind of leadership that puts our competitors on notice.”

Someone turned up the music at the wrong time; the volume swelled and then dipped, like the night itself was holding a breath. Then he did it—the flourish, the smile that never reached his eyes, the oversized check with Kevin’s name in glossy ink and a string of zeros that made one of the junior engineers whisper “holy—” before thinking better of finishing.

“Securing this patent puts Innovate Dynamics a decade ahead of the pack,” Mr. Harrison said. He clapped Kevin on the shoulder as if knocking him into the role would make him fit it. “Director of Innovation, ladies and gentlemen. A new era.”

The room applauded. I did too, because some reflexes prove you’re still human even when the people you trusted treat you like a spare part. Kevin bowed awkwardly. He’d gelled his hair into a style that looked like it took longer than his due diligence would have. When our eyes met, he lifted his glass in my direction—playful, triumphant, unaware of the cliff’s edge he’d just danced over.

The patent number they projected behind him was mine. The diagrams tracing process flow from sensor to signal to outcome were mine. Two years of nights and weekends, a thousand lines of code that had felt like music when they finally stopped throwing errors, and a tidy stack of lab notebooks whose pages still smelled faintly of solder and coffee—mine. We had filed it as a team because that was the way this company used to work. Two months later, my name was mysteriously missing from the continuation. Three weeks after that, Mr. Harrison stopped returning my emails about the variance on Claim 3.

I stood at the back and smiled, and no one in that ballroom knew I was smiling because the man they’d pushed out of his own company had left me something better than a goodbye cake.

“Walk with me,” he’d said, two years earlier, the day he cleaned out his office. The desks were half bare. The plant he watered every Monday had been wrapped in newspaper like a fragile window. He took me not to the elevator but to the stairwell and all the way down to the parking level, where the air smelled like rubber and timing belts and an era ending. He handed me a folder with a single sheet of paper inside and a USB drive tucked into the pocket.

“For one dollar,” the paper said, “I, Thomas Davis, transfer to Chloe Park fifty-one percent of the voting shares of Innovate Dynamics, to be held in trust by—” and then there was an LLC with a name as beige as a lobby couch. There were signatures. There was a notary stamp. There was a whispered “be patient,” which at the time felt like a fortune cookie someone else would get to read and later would feel like a key I could only use once.

“Why me?” I had asked, because it felt like catching a falling house.

“Because you love the work more than the way it looks when you hold it up,” he said. “Because he’ll never see you coming. Because there is more than one way to keep a company you built alive.”

I told no one. I learned to nod at the quarterly slides about “strategic pivots” without standing up to say “we’re drifting.” I kept my head down and shipped features and promised my team I’d protect them when the meetings got sharp. And when Mr. Harrison realized Kevin would never be more than expensive wallpaper unless someone else did the hard labor, I became that “someone else” so often I forgot what my own name sounded like when said with respect.

Patterns don’t usually present themselves on a schedule. They creep—death by a thousand omissions. He took my keynote slot at ElevateConf (“we can’t spare you from the shop,” he’d said; Kevin had fumbled the talk so badly our Slack lit up in pity). He denied my grant request to build a prototype that would have leapfrogged our closest competitor (“fiscal prudence,” he’d said) and then approved a six-figure budget to install a nap pod in Kevin’s office and a barista station that made better coffee than the café downstairs. He called me “indispensable” in meetings and “overly emotional” in reviews in the same breath. He used my work to impress his board and used his board to put me back in my place.

And then he used his firing power. He called me in a week before the shareholder meeting to say, with sorrow he’d borrowed from a better actor, that my position had been eliminated. He used that word—eliminated—like my life was a line item he could delete in Excel. He offered me twelve weeks of severance and a paragraph of praise I could paste into my LinkedIn if I made sure to remove any implication that I’d disagreed about who’d invented what.

“Security will help you pack,” he said.

Across the hall, Kevin was already swiveling in my chair. He put his feet up like a sitcom prop. He waved with the fingers that held my pen. “No hard feelings,” he said. He had no idea feelings weren’t the currency in play.

I balanced the cardboard box on my hip and let the guard walk ten steps ahead. I didn’t look back because the room didn’t deserve my eyes in that moment. I went home and put the USB Davis had given me on the table next to the folder. I called Sarah.

Sarah doesn’t waste time on sympathy you can’t deposit. “Come to Molasses,” she said. It was the coffee shop four blocks from the office, the one with chairs too heavy to drag, where people who didn’t want to be overheard pretended they were reading. She opened her laptop and let the numbers talk.

“Here,” she said, tapping across a spreadsheet. “Expense accounts disguised as consulting fees. Same vendor. Same month. Work done for projects he wasn’t assigned—language is too murky to prosecute if we don’t time it right, but enough to show the board what they need to see. And this—” another tab, “—is your patent’s chain of custody. Claim edits. Committee votes. Redactions. If you squint at the change log you can still see your initials in the margins where they didn’t scrub.”

She didn’t ask if I was ready. She asked if I was done waiting. When I nodded, she closed the laptop and smiled without showing teeth. “Good. He booked the annual meeting in the big room so he could pan for applause. The projector is ours if the majority owner says it is. You coming?”

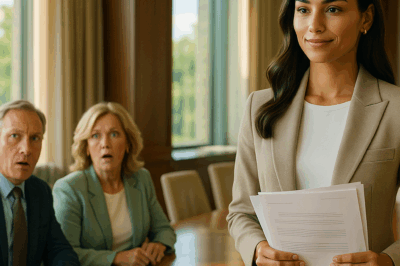

“Security,” Mr. Harrison had barked when I walked into that big room the next morning, my badge deactivated and my smile too calm to be a crime. The guards stepped forward and stopped when Sarah raised her hand and said, “Actually, she has more right to be here than anyone.”

She clicked, and the screen behind the lectern woke up with a bluescreen of ownership records that make men like Mr. Harrison instantly polite. “Per the bylaws,” she said, “the majority shareholder has called an emergency vote. Anonymous controlling interest, fifty-one percent.”

Mur-mur. The precisely calibrated whisper of people who forgot the silent partner exists. “Who?” Mr. Harrison barked, his face going from pink to the white that scares daughters at doctors’ offices.

I didn’t make them wait. “Me,” I said into a microphone that made my voice echo even in my own bones. “I’m that shareholder.”

He laughed the way men laugh when they feel a stone in their shoe and decide to ignore it. Sarah put up the slides. Wire transfers to an LLC run out of Kevin’s condo. Expense reports submitted on Christmas Day. Conference invoices that never corresponded to travel. The email string where my name was replaced by a string of asterisks in a patent document so carelessly that if you highlighted the page the text turned up like a ghost. When she showed the nap pod purchase order, someone in the back actually snorted. It wasn’t pretty. It was precise.

“As controlling owner,” I said, “I call for a vote to remove Mr. Harrison as CEO effective immediately and to terminate Kevin Harrison’s employment for cause.”

Hands. Every hand except two and two turned palm up. It’s funny what ships quickly and what sinks slowly and how, if you’re not watching, you can confuse the two.

The guards Mr. Harrison had called to escort me out escorted him instead. They did it without cuffs because optics matter and because Sarah had told the officers waiting outside to be discreet. “There are detectives on their way who will need to speak with you in a moment,” she said softly, as if telling him his lunch date would have to be rescheduled.

He opened his mouth on lawyers and malice and you can’t and got as far as the first consonant before he realized the floor he thought he’d laid for himself was now on someone else’s foundation. He didn’t look back either, which I took as a kindness I could write down and use later.

The board’s vote to appoint me interim CEO was unanimous. I didn’t stand on the stage and unspool a mission statement. I thanked them. I made Sarah COO on the spot because you don’t get to this point without knowing who picked up pieces when you were busy counting them. I promised transparency and made a note to ask Marta from Facilities to schedule a deep clean of the executive floor because the carpet smelled like cigar smoke and something else stale that I refused to carry into a new era.

Outside, the interns waited with someone’s donut box repurposed as a podium. Someone had written WELCOME BACK, CHLOE in thin dry erase letters across the top of the glass wall next to reception. The engineering team stood like they were trying to keep their bodies from doing something embarrassing with relief. My phone buzzed with texts I was too careful to read yet. Davis had sent just a single ellipsis, which made me laugh hard enough to scare a bird that had ridden in on an errant shoulder when someone propped the loading dock door open last week.

That afternoon, I called a full hands. “We’re going to do three things,” I said. “We’re going to put the work back in charge. We’re going to pay people on time. We’re going to answer emails within a day, because respect is a feature customers can feel.” There was applause—tired, hopeful—and a cheer from the back where QA sits that made me wish we’d allowed whooping in meetings sooner.

Then I went into my new office, which used to be Mr. Harrison’s. I didn’t sit in his chair because power isn’t in the furniture—something he’d never learned and I intend never to forget. I stood and breathed and called the person whose name I should have been calling two years ago instead of grinding myself down to dust in rooms that were never going to value me for more than my output.

“Mr. Davis,” I said, when he answered. “We’ve stopped the bleeding. It’s time to start the building.”

He chuckled. “Knew you would. Now it gets fun.”

Part Two

The first week after the coup—the word fit even if it tasted too sharp to swallow—felt like a time-lapse video of ice melting. Everything was wet and cold and slippery, but you could see what you’d get if you kept the air moving long enough.

We did triage. Fraud audit. Vendor calls where I said the words “We’re sorry” and meant them. Reviews for the people who had been told “next quarter” so many times the phrase had become a curse. We looked at every line item like it was a decision we could make differently and didn’t pretend the nap pod expense wasn’t funny in a way that laughter can heal.

On the third day, HR knocked softly and said, “There’s a Kevin at reception.” I took the meeting not because I had to but because I wanted to look the boy who stole my pen in the face and decide how much of my life I would let him carry.

He sat across from me and tried to smile. He went for charm and landed on tired. “I got played,” he said before I’d asked a question. “He promised he’d take care of me. I’m—” he rubbed his eyes. “I’m sorry.”

I didn’t say “for what,” because the ledger was long and the line for “sorrys owed” wound around the block. I asked what the hardest thing he’d done that week was. “Tell my mother,” he said. “She keeps asking me when I’m going to sue you for emotional distress.”

I made the smallest mercy I could afford. I told HR to code his termination as “ineligible for rehire” and nothing more creative. I learned something as his shoulders dropped that looked like the beginning of a spine. I did not hire him back. That is not my redemption arc to write.

I called the general counsel who’d spent two years trying to get Mr. Harrison to sign ethics training certificates. “We need a policy with teeth,” I said. We wrote a code of conduct that measured managers by the health of their teams instead of the volume of their voices. We published salaries. We set up an anonymous way to blow the whistle that routed to Sarah and two outside auditors, not to the inbox of the person you might need to report.

The first product launch after Harrison felt like standing on a different planet. We rolled out the logistics module Kevin had mocked in front of a leaderboard of customers who had no idea it had been living in my notebooks and nightmares for a year. We shipped on time. We got quiet emails at 3:07 a.m. from ops managers who had been on the floor for twelve hours and took the time to say “this works” because gratitude is a reflex you can’t train away.

The stock price tripled in six months. Then it quadrupled. I gave Sarah a raise she tried to refuse. She rolled her eyes when I told her she was getting a parking spot with her name on it because recognition makes her itchy and then cried in the elevator when no one could see. We all do it our own way.

The police gently squired Mr. Harrison onto the nightly news in a coat that didn’t fit. The court transcripts read like a bad procedural and a good accounting class. The judge used the word “brazen” and the phrase “breach of fiduciary duty” and I did my best not to frame the articles like trophies in my mind. Justice can turn too quickly into a personality trait if you keep it on the wrong shelf.

He went away for seven years. Kevin got probation and community service. A reporter asked if I had a comment after sentencing. “We’re focusing on the work,” I said, because good sentences should remind people of the verbs that move mountains, not the nouns that sit on top and call it a view.

People expected me to call my parents. Or to attend the little group they go to on Sundays where people say “if I had only known” into coffee cups. They wanted a tidy end where the girl raised on being last gets to be first and picks up her prize and goes home to write a thank-you card to the God of Closure.

There’s a different ending that feels truer in the hand. My mother sent me a text with a selfie of the two of them in a small apartment with a window that looks out at a parking lot, and underneath she wrote, “We are safe. We are sorry. We are starting over.” I typed “I hope so.” Then I deleted it. Then I typed, “I hope so” again and sent it because sometimes the kindness you can give is the absence of a speech.

A month later, I saw Brandon at the grocery store buying instant noodles and humility. He caught my eye and gave me a half smile that looked like something on the way to honest. “You were always better at this,” he said. He didn’t mean shelf-stable pricing. He meant not letting bitterness calcify. I shrugged and asked if he wanted a referral to a coding bootcamp. He laughed like the idea was both terrifying and funny and said, “I might.”

You might expect a romance here, or a long weekend by a lake where I scatter stones with names written on them. What I wrote on my calendar instead was “meet with procurement about women-owned supplier pipeline.” In the old era, words like that got stuck in Corporate Responsibility decks and never got budget. We gave it a budget. Six months later, thirty percent of our suppliers were companies founded by people who walked into rooms like the one I used to sit in and were told to whisper.

I put a plaque in the lobby under the timeline wall. Not with my name. With Davis’s. “For giving away power to preserve it,” it reads. I sent him a photo. He sent back a thumbs-up emoji and then called because some things deserve a voice. “Proud of you, kid,” he said. “You turned the company back into the thing we told people it was.”

When I finally opened the folder from the day of the transfer again—paper slightly curled at the edges now, the notary stamp as crisp as guilt—I realized the thing Davis had given me for one dollar was not just a controlling share. It was delayed permission. He had known I needed time to grow into someone who could use that document without it using me. Power tries to teach you shortcuts. Patience is the long way that gets you home.

On the one-year anniversary of the meeting, I stood on the same stage where Mr. Harrison had tried to fire me and where I’d fired him instead. The company had tripled. The product roadmap was a real road map, not just a gallery of buzzword magnets. The floor was full of people whose names I finally knew because no one expects you to remember after two thousand but people deserve it anyway.

“Here’s what we learned this year,” I said. “That building something is not the same as buying something. That transparency is a lever, not a liability. That the best ideas do not come from the loudest mouths but from the quietest corners where someone’s been testing without a deck for months.”

“Here’s what we’ll do next year,” I continued. “We’ll keep our commitments. We’ll write emails you don’t need a translator to understand. We’ll set a service-level agreement with ourselves and meet it, because the way you treat your people is the way your product feels in your customer’s hand.”

I did not say Harrison’s name, or Kevin’s. I did not say my parents’. I said “we” sixty-one times. I said “thank you” twice. I said, “Go back to work,” and everybody laughed because the joke landed on a bed of respect instead of resentment, which is the only way to tell one without leaving a bruise.

After the applause, I went to my office—the chair still not sat in, the plant thriving as if relieved to be free of its past. I poured myself coffee, the kind that had replaced the nap pod in our department’s legend, and stood at the window. The city did that thing cities do where the same metal and glass can scare you and save you, depending on how the light hits it.

My inbox had a note from a student at the community college where we’d set up the scholarship. “I got my first customer,” it read. “I put the sign up. People keep asking me about the font. I tell them the story instead.” I smiled. Story and font matter. Story and font have always mattered. But you can only hang a sign on a place you’ve let become yours.

People will tell you this is a revenge story. It’s not. Revenge implies I spent my nights picturing Mr. Harrison’s face when the cuffs clicked, that I practiced lines in the mirror that would make a boardroom freeze. Justice is quieter. It looks like a meeting that starts on time and ends early. It looks like a bank transfer to a scholarship fund and a hire who never thought they’d get a shot and now leads a team that thinks they hung the moon. It tastes like water, not blood.

When my father wrote me a second letter—the one where he described a mistake he’d made in 1989 and how becoming the kind of man who could not apologize for it took him thirty years—I closed my office door and cried. Then I wrote back, “I forgive you, but forgiveness is not the same as forgetting. If you want coffee, Thursday at ten, two blocks from the warehouse.” He came. We sat. He didn’t try to sell me anything. We talked about the weather and how a forklift teaches you patience.

After he left, I pulled up a blank document. Title: Succession Plan. There will come a day when I hand this company to someone else, and I want the document that gives away control to be as generous and clear as the one Davis gave me for a dollar, which is to say not really about the paper at all. I typed the first line: When in doubt, choose the person who loves the work more than the applause.

In the end, Mr. Harrison didn’t lose because I won. He lost because he forgot what a company is—a collection of people moving in roughly the same direction who need someone to clear the path and paint the lines, not someone to stand on the path and enjoy the view. He lost because he thought the power was in the chair. He forgot the power is in the person who decides whether they sit down.

Tomorrow the papers will run another story. They will use the photo where I’m holding the trophy and the engineer behind me is mid-cheer. They will name me a “self-made woman,” and I will cringe because the phrase ignores the Tuesdays when Sarah stayed late and the Saturdays George brought donuts and the Monday mornings when Marta made the warehouse smell like mint. I will call the reporter and say, “Please put the names of the people whose emails end in @innody. They built this.”

There’s a line I wrote across the whiteboard in Conference A the day after the meeting and never erased. People add doodles to it now and then, because that’s what you want a company to become: something many hands improve. It says: Sometimes the quietest person in the room has the most power. Not because she took it. Because she waited long enough to use it right.

I think that’s the real ending. Not the part where he leaves or where I do. The part where the room—this room, that room, the ones you’ll walk into after reading this—learns to hear the person whose voice almost didn’t survive the year she needed it most. The part where she says, “Here is where we’re going,” and the room—not just clapping now, but moving—goes.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

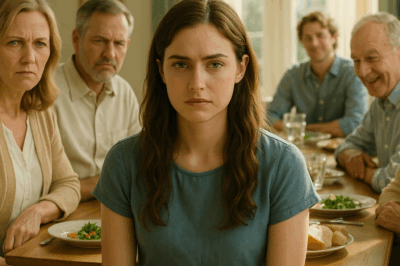

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load