My Best Friend Crashed My Anniversary With a Bombshell About My Husband’s Betrayal, So I Set a Trap

Part One

There’s a way a house hums when a party goes well—low, contented, as if the walls are pleased with the people inside them. My house hummed that night. The jazz quartet tucked beneath the stair landing had found their groove. Someone had discovered the basket of pashminas out on the deck, and every woman I loved had a soft color draped over her shoulders like blessing. Caterers in black aprons flowed from kitchen to living room with trays of canapés I couldn’t pronounce, and the bar—God, the bar—was a constellation of cut crystal under the pendant lights I’d insisted upon during the remodel: walnut, brass, river of marble.

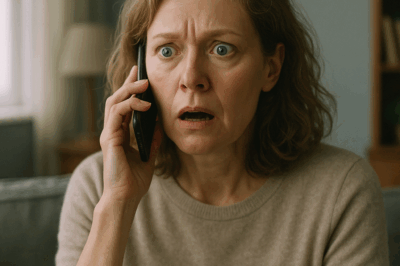

Our fifth anniversary looked exactly like the sort of life you might post and caption with something breezy that makes your college roommate mute you for a week. It felt like that life, too—right up until Lily’s fingers shut around my forearm at precisely 9:17 p.m.

“You need to see this.” Her nails bit crescent moons into my skin. She was much shorter than me, but her gravity was immense. Worry had widened her pupils to the size of coins. I set my champagne on the nearest surface and let myself be hauled through the crowd. Clayton—always hovering near the bar like an attractive houseplant—raised his glass at us. I lifted my eyebrows at him in apology. “We’re about to cut the—”

“It can’t wait,” Lily said. She had the look of a person who has been standing at the edge of a swimming pool for a very long time and has finally decided to jump.

We pushed into Todd’s office and she shut the door, the music folding itself into a dull thrum. The room smelled like cedar polish and his cologne. He’d left the glass barn doors unlatched earlier so people could admire his vintage globe and the mid-century desk he’d found at a place that does not put prices on tags. I loved this room—had loved it—because it was where I had sat on his lap and said, “I think I’m going to call it Blue Door,” and he had said, “For the way opportunity looks from the other side,” and my couture line had been born in that sentence.

“I wasn’t snooping,” Lily started, which is what you say when you were not looking but did indeed find. “I came in for napkins—you said the extra ones were in the credenza.”

“And?” My voice was light. The air was not. The photographs of us on the wall—honeymoon on a scooter in Rome, his hand over mine on the wheel—felt suddenly like props.

She handed me her phone. A banking app glowed on the screen, my company’s crest neat as a signature at the top. Numbers beneath. Rivers of numbers. “He left his laptop open,” she said. “This—this was on it.”

I didn’t understand at first. I am good with fabric and color and people; numbers impress me in the way fireworks do—beautiful when arranged by other hands. But even I could see the directionality: out. Transfers from Blue Door’s operating account to something offshore with a name that sounded like a skin care line. One transaction closed off the bottom of the screen, and I scrolled, my finger slick with sweat. There were more. Smaller ones. Dozens, spread like breadcrumbs across months. Half a million dollars, layer-caked out of my life.

“No.” I could hear my voice from the other side of the desk. “No, I’d know. The balance. Cash flow.” All those nights he’d sat here with me, glasses of wine balanced on the edge of the desk, saying, “You worry too much about payroll. Let me run the numbers,” his profile handsome in the glow.

“There’s more.” Lily’s voice had gone soft with effort. “I took screenshots.”

She swiped. An email thread opened. “The wife doesn’t suspect anything,” Todd had written to a name that made my stomach turn: Daisy Ford. “Two more months and we’ll have enough to make the move.”

The wife. I scrolled. Daisy—my Daisy, my head of sales, the woman whose toddler I had held while she redid her eyeliner in the ladies’ room at our first New York show—had replied, “What about the business?” And Todd, my husband, had typed, “She’ll be too busy dealing with the audit to notice we’re gone.”

Audit? I hadn’t scheduled an audit. My glass slipped, red wine spreading into the cream carpet like a wound.

“Heidi—” Todd called from the hall in the voice that once turned my name into a kind of prayer. “Babe, where’d you go? Everyone’s waiting!”

Panic shot in like lightning. Lily grabbed my elbow again. “Don’t let him know you know,” she said. “Not yet. We need to see how deep this is. The audit—what audit? If he’s setting you up—”

The handle turned. I kicked the glass under the desk and swiped my cheeks with the sleeve of my dress; the face I made in the mirror when I cut the ribbon on my first store arranged itself on my bones like muscle memory. The door opened and Todd filled it—dark suit, no tie, the haircut I scheduled for him every three weeks. Everything about him said, I am a man who remembers birthdays. He smiled at the two of us like he’d walked in on something amiable and feminine, like an Instagram story he would never watch all the way through.

“There you are,” he said. “What are you two hiding? Is it edible?” He had dimples. I had to remind myself that dimples are simply shadows.

“Girl talk,” Lily said smoothly, the quicksilver of her poise reminding me why we had decided, at nineteen, that we were going to be each other’s emergency contacts. “You know how I get when I have a crush.”

“On a human?” Todd raised an eyebrow and reached for me. I stepped into him because that is what wives do when their bodies have not yet learned new tricks. His arm slid around my waist and I concentrated on the fabric of his jacket under my palm so I would not think about the laptop sitting open across from us like a wound.

“We’re about to cut the cake,” he said into my hair. His breath smelled like champagne. “Five years,” he murmured against my temple, “and I still can’t believe you’re real.”

Five years, I thought, and I still believed you were.

The room erupted when we reappeared together, as if applause could fix anything. The cake was divine—white chocolate and raspberry and the fondant bows that I pretended were gauche until I saw them executed so perfectly I wanted to kiss the baker. Todd raised our joined hands and someone shouted, “Speech!” and he squeezed my fingers, oblivious to the storm.

“Want me to do it?” He glanced at the knife. “Or you?”

I wrapped my fingers around the handle. The reflection in the blade looked like someone who was good at pretending. “Oh,” I said brightly, meeting his eyes across the knife’s polished edge. “I think it’s my turn to cut something.”

The party ended in a blur of air kisses and “let’s do dinner soon” said to people I never wanted to see again. Todd stood at the door warmed by praise, slapping Clayton on the back, telling the quartet they were “magic, just magic,” looking every inch the asshole of the year’s husband. “You okay?” he asked when the last guest left and the house held only us and the faint smear of roses.

“Just tired,” I said. “It was… a lot to take in.”

“I know what you mean.” He slid his arms around me from behind and rested his chin on my shoulder. The weight of him turned my bones to metal. “Five years,” he said, because he likes to repeat things for emphasis. “I can’t believe how lucky I am.”

Lucky. The word stuck in my mouth like a seed.

“Go up,” I said, twisting out of him gently. “I’ll tidy a little. You know I can’t sleep when there are champagne flutes out.”

“Leave it for the service,” he said. “Come to bed.”

“Two minutes,” I lied. He kissed the unhurt side of my face, said, “Don’t be long,” and padded upstairs.

I waited until the bedroom door closed. Then I took his laptop and what was in his bottom desk drawer—the folder where he kept the things he told me were boring—and I spread everything across the marble island because if my life was going to be in pieces, the least I could do was arrange them on a surface I loved.

The laptop had a password. I tried our anniversary, his birthday, my mother’s maiden name. No luck. After the fifth attempt, I stopped; I had seen enough of Todd’s temper to know what locked accounts could trigger. The drawer yielded household detritus and, after two insurance policies, an envelope labeled tax prep that did not belong to the woman whose name was on the storefront on Third and Pine. These were not the statements I reviewed with my accountant every month. These were cousins of my numbers—similar enough to be believable, romanticized enough to undermine me in front of a very bored IRS agent.

The doorbell rang.

I nearly threw the laptop into the sink. It was 1:04 a.m. I peered through the peephole and saw Lily standing on the porch in her old high school hoodie, hugging herself like the night had teeth.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she said as I pulled her inside. Her eyes looked like hell and loyalty. “I kept seeing your face.”

“Todd’s upstairs,” I whispered. “He thinks I’m… polishing silver.” I handed her a towel because that’s what women do in kitchens when their lives are on fire.

She took in the island. “Jesus.”

“And this.” I spread out the falsified statements. “For the audit he invented.”

She scanned, her frown deepening. “He’s keeping two sets of books. One for you. One for wherever he’s moving your money.”

“He mentioned an audit in those emails,” I said. “If he schedules one, with the numbers he fabricated—”

“He makes you the fall guy,” she finished softly.

“Heidi?” Todd called from upstairs. The house carried his voice the way houses carry songs you don’t like. “Who are you talking to?”

Lily’s eyes widened; she stuffed the papers into her tote. “She forgot her phone,” I called back, spotting the disposable lifeline she had left on the lip of the sink hours earlier. I held it up as Todd walked in wearing pajama bottoms and a frown.

“Everything okay?” he asked, and his voice made me want to throw my beautiful marble out the window.

“Fine,” Lily said with perfect affect. “I couldn’t find my phone. Heidi found it.”

“Good,” he said, staring at the island as if waiting for it to embarrass us. “Babe, come to bed.”

“Two minutes,” I said again, and smiled with teeth.

He padded away. Lily’s hands shook when she reached for mine. “You need help. Not from me. Someone who does this.”

“Therapy?” I half-laughed. My hysteria didn’t land.

“A private investigator,” she whispered. “Warren. He lives in a sensible blazer. He specializes in financial fraud.”

“A private investigator,” I repeated. The words felt dramatic and adult in the worst way.

“He’s the person you call when someone like Todd thinks you’ll never fight back,” she said. “Let me call him.”

“Call him.”

Warren chose a coffee shop fifteen miles away with mismatched chairs and a chalkboard menu. Ordinary. It felt like a place where nothing bad could happen to anyone.

“You must be Heidi,” he said, and his handshake was firm without competition. He didn’t look like a PI in a movie; he looked like my dentist’s brother. I found this comforting.

“Lily filled me in on the headlines,” he said. “I need the story.”

I told him. I told him in a straight line even though I wanted to walk around the words. Half a million dollars tucked into offshore shells. Falsified statements that would look like my failure in fluorescent light. Daisy in my inbox. An audit I hadn’t ordered. I told him about the night Todd had held me while I cried about making payroll during the pandemic and had said, “We’ll figure it out—we always do,” and how I had believed him so much I never checked whether he had fingers crossed behind his back.

“How much?” he asked when I ran out of breath.

“Five hundred across months,” I said. “That I’ve seen. Could be more.”

“And the business?”

“Growing.” The word tasted like ash. “I thought.”

“Who has access to your accounts?”

“Me. Esme—my bookkeeper,” I said. “She’s twenty-eight and relentless and exactly who you want in your corner. Todd reviews before anything goes to the accountant.”

“People like your husband rely on that,” he said. It wasn’t unkind. It was anatomy.

My phone buzzed. Lunch? Daisy. I showed it to him.

“Meet her,” he said.

“You want me to… spy?”

“I want you to collect information in a way that keeps you safe,” he said. “Right now you are an investigator in your own life. Information is oxygen.”

We spent an hour with me giving him everything: passwords, bank names, the last four of an account number I had memorized accidentally because I’d put it on so many ACH forms. He wrote it all down in a notebook that looked like my father’s ledger book used to look when he did plumbing jobs out of the garage.

“One more thing,” he said at the door. “Do not confront him. Not yet.”

“Already did,” I said, and then covered my mouth.

He winced. “Desperate people—”

“—burn the house down,” I finished. “I know. I won’t be alone with him again.”

I went to the office to remind myself that something was still mine. The designer I used to be before I became a CEO had always trusted what fabric does when you cut it on the bias; I tried to do the same with my people.

“Morning,” Esme said. She had three coffees lined up like mathematical proofs and a mess of spreadsheets on her screen. She gave me the expression she gives when a number refuses to behave. “Whoops—you’re here. I thought you’d be nursing a hangover.”

“Coffee,” I said, too brightly. “And truth.”

“I’ve been meaning to talk,” she said, lowering her voice as if the walls might want to listen. “Some of the reports don’t reconcile. Small things—a vendor I can’t verify, a three percent wobble in expense allocation. When your—when Mr. Tate came by last week, I tried to ask him.”

“When he came by,” I repeated. It made sense—he wouldn’t do it in my inbox if he could do it on my hard drive. “And?”

“He told me he’d handle it.” She bit her lip. “I… kept notes.”

I loved her, in that moment, more than I had loved anyone in months. “Good,” I said. “We keep this between us. For now. Send what you have to Warren.”

“Warren?” Her eyebrow lifted.

“Our PI,” I said. The way her face relaxed told me she had been holding this alone.

Lunch with Daisy was an award-worthy performance. She wore a silk blouse that screamed good at sales and ordered a rosé that made the waiter clap inside.

“The party,” she cooed. “The flowers. Todd was—” She fluttered her fingers in the air. “A dream.”

“Isn’t he,” I said, and enjoyed the taste of bile.

“Let’s talk expansion,” she said, laying a folder on the table like an ace. “We should move faster. Ten markets. Todd says the timing is—”

“Perfect,” I finished. He said that about everything he wanted me to sign. I swallowed. “Meridian Consulting?” I asked, casual, like the name had just popped out of a dream.

Something flickered across her face—alarm, guilt, calculation. “Market research,” she said smoothly. “Todd handled that contract. They were… small but effective.”

“It’s odd,” I said, looking wholly innocent. “I don’t remember approving it.”

“You were… finalizing the spring show.” She smiled sweetly. “You have so much on your plate, Heidi.”

“I do,” I said, meeting her eyes. “Good thing I’ve learned to share.”

She hugged me on the sidewalk when we parted. “We’re going to do great things,” she said. I did not ask who she meant by we.

Warren was waiting for me that night with a calm that made me want to take off my shoes and put my head down on the table like a child. He spread out his own neat exhibits under my pendant lights.

“Meridian is a shell,” he said. “Registered to a PO box. The signatory?” He slid a sheet toward me. “Clayton Mitchell.”

“Clayton,” I said, as if saying his name out loud might turn it into something it wasn’t. “Clayton from college. Clayton who calls me ‘kiddo’ even though we’re the same age. Clayton who—”

“Clayton who incorporated a consulting firm six months ago, who received $75,000 from your company for services not rendered.” He flipped another page. “Clayton who, with your husband, has booked one-way tickets to Bali.”

I didn’t flinch at Bali. I am in fashion; half my clients take resort selfies on Wayanad and can pronounce Uluwatu. “When,” I asked.

“Friday,” he said. “Unless they move faster.”

Todd texted Dinner. Big news. He wanted me in the blue dress he likes—the one that fits like a lie. I wore it because sometimes ghosts must be appeased before you can exorcise them. He took me to Luciano’s where we’d had our first date and kissed me on the cheek and ordered my favorite without asking.

“I’ve been working on something,” he said, eyes lit with the sort of excitement men like him use to sell sun to the sky. “An investor. Big. Eight figures.”

“With Clayton?” I asked lightly. He didn’t blink. “James Westfield,” he said. “Tech guy. Wants to diversify.”

“Westfield,” I repeated like I might have heard it somewhere, not because the name had been made up by a man who thought novels are written by people who don’t exist yet. “Impressive.”

“We have a meeting next week,” he said, squeezing my hand. “In the city.”

Next week is a phrase greedy men use to keep the world from happening on time. I drank my wine and tasted the goodbye he wasn’t saying. He looked so pleased with himself. It would have been pathetic if it weren’t so dangerous.

It All Went Sideways.

That’s how the women in my mother’s book club describe plot points when they don’t remember character names. In my life, sideways meant the email on Todd’s computer from Clayton saying, Audit flags. Move timeline up. Details in morning. Sideways meant confronting Todd because I am, at heart, an earnest idiot who believes in the power of questions. Sideways meant his hand around my arm, hard enough to leave finger-shaped bruises, and his mouth saying, “Every transfer has your signature,” like victory, like rot. Sideways meant me diving out the guest bathroom window while he pounded on the door, the lattice snapping under my thigh, something in my ankle screaming, We did not agree to this.

Lily’s door was unlocked. She had a throw on the sofa and a glass of water that made my eyes sting. The police came because she called them. The female officer had hair like mine used to be and hands that were warm. She took photos of my arm and said, “We can go with you to get your things,” and for a moment I loved her with an intensity I reserve for strangers who choose compassion around 2 a.m. The male officer asked if there were firearms in the house. “Only knives,” I said. “For cake.”

Warren arrived with a folder so thick it felt like a gift. “We have enough,” he said. “We move tomorrow. He thinks he’ll be at a meeting with Westfield.”

“There is no Westfield,” I said.

He smiled a small, sharp, excellent smile. “Not yet.”

I did not sleep. I reached for my ring, twisting it around and around until I realized I had already put it at the bottom of my purse between a lip gloss and a receipt for thread.

At 9:00 a.m., I sat at the head of a conference table in a building with a lobby designed to impress, my spine performing competence while my stomach rehearsed grief. Warren stood to my left. Two agents from Financial Crimes sat on the other side, trying to look like lawyers. The woman from the prosecutor’s office had the kind of pen your hand wants to steal.

The door opened. Todd walked in with the grace of a man who believes doors exist for him. Daisy followed, professional smile fixed so hard it might crack enamel. Clayton came third, smoothing his tie like a gambler who has forgotten which pocket hides the ace.

“What is this?” Todd asked, and to his credit, he sounded bored. “Where’s Westfield?”

“There is no Westfield,” I said, because maybe some sentences deserve to be said twice. “Sit.”

He didn’t. Men like him don’t sit when women tell them to.

“I think this is yours,” I said, sliding the first document across the glass. Transfers to a bank in a country with good beaches and poor morals. Stamped and neat, each decimal exactly where it should be.

He flicked the corner of the page with his finger like it was a menu. “You don’t understand,” he said. “Those are investments.”

“Of faith,” I said. “You took my company’s money and invested it in your escape.”

Warren slid the Meridian incorporation papers across next, Clayton’s signature big enough to signal insecurity. Clayton swore. “She’s lying.” He looked at Todd. “Tell them.”

“You loved her once,” I said, because every trap needs a moment of truth. I didn’t say it to make him cry. I said it to make him ugly. It worked. He rolled his eyes.

Daisy’s smile cracked. “Tickets to Bali?” I asked, turning the laptop to show the receipts. “For two.” I watched her eyes widen and knew the part of the story she had not been told. Daisy recalibrates quickly. It’s why I hired her. She stood. “I want immunity,” she said to the prosecutor. “He planned it,” she said, pointing at Todd and not even pretending she had not enjoyed planning it with him. “He told me Heidi wouldn’t notice. He said she cared more about dresses than dollars.”

“Daisy,” Todd hissed.

“This is a waste of time,” he said then, to me, to Warren, to the agents, to the walls. “I want my lawyer.”

“You’ll get one,” the prosecutor said. “He’ll meet you downtown.”

I pressed the button on Warren’s phone. The recording of Todd’s voice unfurled into the room like ribbon: Every transfer, every document, it all has your digital signature. My voice followed, steady in a way that made me want to hug the woman who had found it under the sink. One hour. Or I release everything to the press.

For a moment, his face changed. It was quick—the truth always is—but I saw the boy he had been when his father left three voicemails in a row and his mother never called back. Then it was gone. “This is illegal,” he said, and the prosecutor looked at him as if he had tried to tell her that gravity was a conspiracy.

The agents did their job with less drama than in movies. They said words like indictment and conspiracy in voices that had coffee in them. Daisy walked out with one agent, her spine arranged into something that tried to look like dignity and almost got there. Clayton chose to sit. Todd looked at me as if I had stepped on his foot on purpose.

“You can’t prove it,” he said again, softer.

“Watch us,” I said.

The door closed. Warren, who had the grace to let silence do the heavy lifting, put his hand on the back of my chair. “You did it,” he said. It sounded like we, which is why I will send him an expensive Christmas present every year until one of us dies.

“What happens to my company?” I asked, my voice small for the first time since Lily took me by the arm.

“You’ll need to work with the forensic accountant,” he said. “Unwinding takes time. But Blue Door is yours.”

It had always been mine. I had let a man sit at my desk and call it ours because marriage is a series of illusions you agree upon until you don’t. Now, in a room designed to make men feel powerful, I reclaimed my place without metaphor.

The house was almost kind when I walked back in, as if it too had been holding its breath. The cleaning service had taken away the evidence of sugar nights. The linen napkins had been folded into a proof that someone knows how to steam.

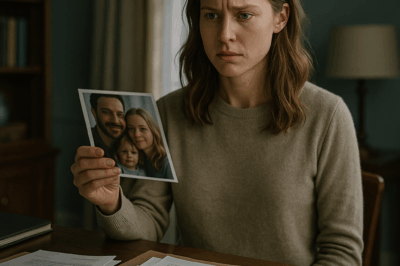

I stood in the kitchen where Lily had said You need to see this and took the framed honeymoon photo down from the wall. We looked young. I suppose we were. He had changed his hairline and his watch since then. I had changed everything.

My phone buzzed. You okay? Lily.

“Better,” I texted back. Come over. Bring donuts. Coffee is on.

“Make it two,” she replied. “We have a house to redecorate.”

I poured coffee, strong enough to insist upon itself, and pulled the notepad from the junk drawer. I wrote a list not of what I had lost but of what I intended to choose:

— change the locks

— call Esme (promotion, raise, title she deserves)

— forensic accountant meeting at 10

— therapist (good one; not the woman who says “how does that make you feel” like a line reading)

— paint the office (no more moody gray)

— sell the suit chair

— keep the table

— learn to trust myself again

At the bottom, I wrote Blue Door belongs to me and drew a square around it and colored it in. It looked childish and perfect.

Upstairs, in the drawer where I kept reminders of what I had thought was permanent, I found the ring again. I rolled it between finger and thumb. It was heavy and handsome and had no value left. I put it back in the drawer and shut it—the soft click of wood against wood the most satisfying sound I’d heard in months.

Part Two

Grief is boring. People don’t tell you that. It has shape and teeth and poetry in the beginning; then it becomes a chore you do because the light is better in the afternoon if your windows are clean. What kept me from drowning in tedium was the business. A company is, if you let it be, a net you weave yourself and then climb. I had work to do.

The forensic accountant arrived in a blazer that could survive war. We clogged a whiteboard with arrows and dates and bank names and the piece in the middle with four letters: BALI. She said things like recoverable assets and discretionary outflows and we can claw this back. I nodded and learned how to keep my spine straight while my heart did plies.

Esme glowed when I called her in. “CFO,” I said to her. “I should have done this a year ago.” She bit her lip and blinked like a person who doesn’t have time for gratitude and does it anyway. We sat together and called vendors, told truths, apologized for the delays we could not explain. People like tailors and button suppliers and the guy who produces our tags were kinder than I deserve. “My cousin got out of something like this,” one of them said. “You call me if you need me to vouch.”

The building began to feel like mine again. The cutting tables laughed. The interns stopped pretending not to whisper. Daisy had been replaced with a woman named Harper who came with references that made you want to drink. “I know Daisy,” she said delicately on her first day. “I will not be Daisy.”

“I didn’t ask,” I said, and then I smiled because grace is a muscle you must stretch or it cramps.

Warren called with updates in a voice that was always almost delighted. “Indictment,” he said one afternoon. “They do love that word. If I had a nickel.” The prosecutor liked the case because financial crimes prosecuted well during reelection years. Daisy took a deal that made me roll my eyes and then roll them back into my head to avoid a headache. Clayton did not. The last I heard, he was in a state that allows redemption if you stop drinking. I think he has not stopped drinking.

And Todd? Turns out, arrogance doesn’t play well with orange jumpsuits. He looked good in court; vanity dies last. He looked at me when the judge said words like conspiracy and wire fraud and breach of fiduciary duty and arranged his mouth into regret, as if he had been practicing in the mirror. It did not land. The judge was not the audience he’d imagined. The audience he imagined had moved to the front-row seats and learned how to set up recording devices.

“It’s done,” Lily said after the verdict as we stood on the courthouse steps holding coffee like talismans. “You did it.”

“I did,” I said, and was not ashamed of the pride.

We did, too. Women operate in chorus.

Blue Door needed an expansion strategy that had nothing to do with ten new locations and everything to do with values. I hired a nonprofit consultant who used to run a kitchen that fed people who could not pay and could not stop being hungry. We designed an apprenticeship program for women who’d been told they couldn’t have another chance. I put a bulletin board in the lobby that said Write your dream and left a box of Sharpies. It filled in two days. We added another board. We left the boxes of Sharpies.

At home, walls changed color. Todd had liked gray. I found a white with the faintest undertone of green and watched my house exhale. I took the artwork off the staircase wall and replaced our honeymoon photo with a sketch by a friend who paints houses like they are faces. I moved Todd’s leather chair to the garage and sold it to a man who wrote Cash on the line that said Name.

Rings went into drawers. Women came over with power drills. We discovered that the granite was not as indestructible as Instagram implies. We learned how to patch drywall. The dog from next door visited. The house learned us.

A letter came from Daisy six months after sentencing—handwritten, the looping generosity of someone who has watched an older woman show her gratitude and thought it was a lesson. “I’m sorry,” she wrote. “I made choices because I told myself I didn’t have any. I did. I know that now.” I wrote back. I don’t know what you write back in these situations. I wrote, “I hope you use your brain for good now,” because I like a woman who knows how to manipulate markets and I would like her to teach my interns about negotiation in three years when she’s allowed to be near a credit card again.

Clayton’s mother dropped off a pie. I hadn’t spoken to her since the party when she cooed at my flowers and told me they were “Instagrammable.” She did not ask for forgiveness. She asked for a receipt. We both knew how it sounded. We ate the pie anyway.

I stood in front of a room full of students at the art school downtown and told them about textiles and trends and building a business without apologizing for making money. A woman in the back raised her hand and asked how to choose partners. “Look less at their pitch and more at their decisions when no one is looking,” I said. “Look at their history with tipping. Look at whether they say ‘we’ and mean it.”

In November, Lily took me to the coast. We rented a house with a sagging deck and a television that could not find a single channel and a kitchen with ash-smeared cabinets. I made bouillabaisse because my therapist says repetition can be healing. We drank wine that tasted like apples and watched the ocean pretend to be still. “He doesn’t get to have this,” Lily said, pointing with her glass toward the sunset. “He doesn’t get the moment where you realize the color you spent the last year seeing in swatches exists in the sky.”

“He doesn’t get to take my color,” I said, and it felt like becoming the woman I thought I was going to be at twenty-one but smarter.

We walked the beach and wrote swear words in the sand. We watched them vanish. We laughed in a way that felt like a good dress—fit close, allowed movement.

Margo came on Thanksgiving with a casserole so heavy I thought it might dent the countertop. She had become the most formidable version of herself in my new life—shrewder and kinder. “I approve of the wallpaper,” she said, which is how she says I love you.

When the appellate court ruled on the motion to reduce Todd’s sentence, I did not attend. I sat at a table with Esme and reviewed fabric swatches and learned the cost of silk has gone up and then up again and said, “We’ll do winter in cotton,” and watched her calculate possibilities on a napkin as if we were starting over in a dorm room and not in an office with a view. We were; I liked it.

Todd wrote from prison twice. The first time he used the word regret as if it were expensive. The second time he used the word love as if it were a tool. I returned neither letter. I took them to my therapist. She made a face I found comforting. She said I could burn them but the city had a drought advisory and she didn’t want to be the person whose patient set the sky on fire.

The best revenge is a life. I had never understood that line until I was too busy to articulate it.

One year to the week after my anniversary party, Blue Door hosted a trunk show in the house. We had open shelving with stacks of sweaters the exact neutral I had once believed would make a person look smart and now used to make my mother-in-law look edgy. We put mirrors in the stair hall and called it a trying-on gallery. We had champagne and a lemonade station for the woman who came in leggings and a T-shirt and looked like me ten years ago when I asked Lily to hold my hair so I could throw up after a bad review.

“Five years,” someone said, standing by the island and looking around like the kitchen might answer. She meant marriage. She meant my face. She meant all the wrong verbs. I arranged a platter of cheese and realized I was simply pleased she was in my house buying my clothes.

Daisy showed up. She had cut her hair. She looked like the kind of woman who drinks black coffee and can fix your printer. “I’m not staying,” she said, holding a paper bag. “I just wanted to drop this off.” Inside was a book—The Art of Strategy. “For Esme,” she said. “And for you.” She glanced around, at the color, the light, the absence. “It’s… still you.”

“It is,” I said. “It’s me on purpose.”

She nodded and left without asking for a selfie.

Warren brought his wife, who wore red lipstick and believed in my cause. Their daughter tried on a cape and refused to take it off. “We’ll send the invoice,” I told her solemnly. She said, “What’s an invoice?” and laid her head on the island, as if marble were soft.

At the end of the night, Lily and I sat on the floor with our backs against the cabinets I’d chosen alone, our feet bare, our glasses half-full. We counted sales and did not say out loud the number it would take to pay for the lawsuit, the accountant, the new locks. We ate the leftover raspberries from the cake whose recipe I’d gotten from a website called Divorce Dessert. We laughed like sinners, which is to say honestly.

“Remember when I pulled you into this office?” she asked, tapping the door with her heel. “And showed you the world ending?”

“Yes,” I said. “Thank you.”

“You would have seen it eventually,” she said. “You always do.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But I like the version where you’re with me in the room.”

If you ask me now, at 10:47 on a Tuesday night in a kitchen that hums with a different kind of music, how I set the trap, I will tell you a list: I didn’t go alone. I listened to my body when it told me it was too tired to cry. I put numbers on paper because paper is an altar in the rooms where really boring men decide important things. I let my best friend pull me into a room and say something that made me hate her for one second and love her for the next hour. I learned to spell forensic. I wore the blue dress like armor and then hung it in the back of the closet like a drag of grief until it became simply a dress again.

If you ask me how it ends, I will tell you the truth: with locks changed, with a dog that is not mine asleep on my foot, with a business that survived because women put thread through needles and then through fabric and then made it fit. With a best friend who is always five minutes away with a key. With a woman who was my head of sales years from now sitting in my office with a title she earned and a salary men think she doesn’t need because they are wrong. With me walking into my own house and not checking my face in the glass because the house is seeing me fine.

So yes—Lily crashed my anniversary party, blew up my feed-and-flower fantasy, and handed me my life back wrapped in screenshots. Todd thought he’d won, with a pregnant mistress and an offshore account and tickets to a country he would have ruined for me forever. He didn’t plan for a best friend who knows how to pick locks with kindness, or a mother-in-law who learned to say my girl with awe, or a private investigator in a sensible blazer who looks at you and says, You are not crazy; you are correct.

What you get out of a trap depends on what you bait it with. I used truth.

It worked.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

End of content

No more pages to load