Part One

The first thing you learn as a Ford is how to smile.

It isn’t a real smile, the kind that reaches your eyes and makes the corners crinkle. It’s performance: a carefully constructed curve that says, Everything is perfect. We are perfect. And you’re lucky to be here. I’ve had six years of practice. I’m thirty-one, my name is Robin, and I have never been worse at it than I am today—standing in the middle of a party that is supposedly for my own daughter.

My mother‑in‑law, Esther, organized the whole thing. At fifty‑nine, she moves with the deliberate grace of a woman who has never been told no. Her house—correction, the Ford family house—is decorated in her signature palette of cream and gold, not the soft greens and sea‑glass blues I chose for the nursery. The guests are her friends, her business contacts, and the longer, shinier branches of the Ford family tree.

My husband, Damian, thirty‑three, circulates through the crowd in a navy suit that costs more than I made my first year out of college. He accepts congratulations with the perfect Ford smile. He hasn’t checked on me in an hour.

One month ago, I gave birth to our daughter. The pregnancy was brutal: nine months of relentless nausea, sciatic pain that made me crawl to the bathroom some mornings, and a final six weeks of mandated bed rest when the doctor frowned at my blood pressure and said, very gently, lie down or lose her. Through it all, the Fords offered platitudes, not support. Esther texted articles about mind‑over‑matter. Damian complained that my “negativity” was stressing him out. The day I finally held our seven‑pound girl, saw the tiny comma of her ear and the way her hand opened like a starfish when the light shifted, I whispered the name I had kept like a talisman through contractions and fear: Isa.

It was the one thing that felt truly mine.

Now I stand in Esther’s living room holding a glass of water I don’t want and watch my mother‑in‑law across the sea of cream and gold. She’s talking to a woman I don’t recognize—sleek dark hair, a confidence that radiates, the polished kind that doesn’t squeak when it walks. My sister, Lacy, materializes at my elbow, a welcome burst of color in a red dress and combat boots. Lacy is thirty‑five, loud, fierce, and gloriously unimpressed by the Ford family’s manufactured prestige.

“You okay?” she murmurs without looking at me, following my gaze instead. “You look like you’re about to burn a hole through that woman’s skull.”

“Who is she?” I ask. My voice feels like it’s been wrapped in cotton and shipped to a different address.

“Don’t know,” Lacy says after a squint. “Never seen her before. But Esther looks like the cat that got the cream.”

She’s right. Esther is beaming. It is the first genuine smile I’ve seen on her face since the day I married her son. Damian joins them, and my stomach clenches as he greets the woman—warmly. Too warmly. He hugs her. Not a polite, stilted family‑hug, but a real one, the kind he hasn’t given me in years. The woman laughs—low, musical—and Damian’s face lights up.

Cold dread creeps up my spine. This party isn’t for Isa. It isn’t even for me. It’s a stage, and I’m the prop no one bothers to put away when the show changes scenes.

The caterers arrived at ten with a menu Esther approved without my input. The florist arrived at noon to replace my daisies with white chrysanthemums. The photographer arrived at one and has largely been photographing the Ford side: bow‑tied cousins, lacquered aunts, and Esther in soft focus. A few times I moved into frame and felt, more than saw, the way the lens drifted back until I was in the periphery again, a smudge of color at the edge.

A silver spoon tings against crystal: Esther calling the room to order. Conversations soften. People pivot toward her as if she’s the moon. Damian moves to her side and lays a hand on her shoulder. He glances my direction for half a heartbeat; his eyes are blank.

“Thank you all for coming,” Esther begins, voice smooth and practiced. “Today is such a special day. We are blessed to welcome the newest member of the Ford family, a beautiful girl who will carry on our legacy.”

Legacy. That word drops into the room like a stone into still water. I can feel the ripple coming before it reaches me.

She pauses for effect, her gaze sweeping the adoring faces. I know with a sick, certain rush that something is about to go terribly wrong.

Esther’s eyes find mine. For a flick of a second, I see triumph—almost cruelty—before the benevolent mask slides back into place. She raises her glass. “Join me in officially welcoming our precious granddaughter,” she says. “Introducing our beloved—Isa Kendall Ford.”

The name echoes—then shatters the moment of silence that follows.

Isa. Kendall. Ford.

The applause is polite, a rolling wave from Fords and their satellites. Compliments bob along: How elegant. So strong. Such a family name.

My heart doesn’t pound. It goes impossibly quiet. I look at Damian. He stands beside his mother, that perfect smile stretched across his face. When his eyes meet mine for a fraction of a second, there is no apology, no regret—only pride. He squeezes his mother’s shoulder. A gesture of solidarity. A blade between ribs.

The dark‑haired woman—Kendall—claps too. A small, knowing smirk plays around her mouth. Kendall Bell: Damian’s high school sweetheart; the ghost who has haunted the edges of our marriage for six years; the person whose laugh Esther quotes, whose taste Esther trusts, whose name Esther just grafted onto my daughter like a brand.

They took the one pure thing I had and tainted it. They renamed my child in front of a hundred people and expected me—no, trained me—to smile.

My skin chills, but my hands are steady. Lacy shoots me a look—fury and concern—and I give the smallest shake of my head. I don’t need her to fight this battle for me. I already fought it.

Two weeks ago, in a hallway that smelled like toner and floor wax and newborn hope, under fluorescent lights that buzzed like fluorescent lights do, I stood across a form and did a thing that women have done since ink dried on paper: I wrote my child’s name.

Damian had been putting off filing the birth certificate. I’ll get to it, Rob, he’d say, waving a hand like the gesture itself did paperwork. It’s not urgent. Meanwhile, Esther’s eyes lit the way a match does when she talked about family names, and one night I came downstairs for water and heard Damian on the phone, voice low and intimate: Don’t worry. Mom’s handling it.

I called Lucas.

Lucas Joseph and I met in college: he’s thirty‑one, kind, gently sarcastic, and—a detail I care about more now than I did at nineteen—a family law attorney who still believes paperwork can be used to bend the world toward right. He met me at a coffee shop, watched me shred a napkin to confetti, and said, “He hasn’t signed anything yet?”

“No,” I said. “He keeps making excuses.” Isa slept on my chest, warm and terrifyingly small.

“You’re her mother,” Lucas said. “Your name is on the hospital records. In our state you can file the certificate yourself. It’s better if both parents sign, but not required when you’re married and he’s listed. If you’re worried someone else is going to do something… do it first. Legally.”

I stared down at my daughter. She smelled like milk and newness. “I’m tired,” I said. “I’m scared I’ll mess it up.”

He put a warm hand over mine. “You already did the hard, brave thing. This is just ink.”

The next morning he drove us to the registrar’s office. I wore yesterday’s sweater and a ponytail I didn’t have the energy to tame. A clerk with soft eyes slid a form through the glass. Mother’s name. Father’s name. Child’s name. I wrote:

Child’s name: ISA MARIN FULLER‑FORD.

Marin was my grandmother’s name. Fuller was mine. The clerk stamped and copied; the seal bit down; the paper came back across the counter heavier than paper should be. It felt like armor. I tucked it into my bag and, for the first time in months, breathed all the way to the bottom of my lungs.

Back in Esther’s suffocatingly perfect living room, the memory stops my hands from shaking. The shock burns away, leaving a cold, hard certainty. They think they’ve won. They think I’ll stand here and make the Ford smile. They think I don’t bite.

I step away from the fireplace. The movement is small, but it draws eyes, the way a bird landing on a branch draws stillness. Damian’s smile falters. I walk to the central table where the champagne flutes and the untouched cake sit like props. I set my purse on the polished wood with a soft, definitive click. The room hushes the way rooms do when they sense plot.

Esther turns, her expression one of mild annoyance—as if the help is about to interrupt. “Robin dear, is everything—”

“Actually,” I say, and my voice is clear and steady. “There’s something you should see.”

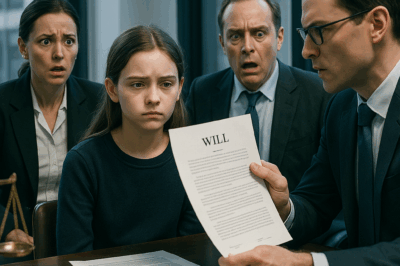

I unclip my purse. The metallic snap is unreasonably loud. I find the folded document by touch. The crisp edge is a comfort. I unfold it slowly, smoothing the creases on the table with my palm. The seal at the top catches the chandelier light.

Damian’s cousin Tyron—thirty‑six, honest as a clean shirt—stands closest. He leans in, brow furrowed. He reads aloud, because he is a man who thinks if he puts words in the air they’ll make sense: “Isa Marin Fuller‑Ford.”

A collective gasp ripples. It isn’t the name that does it; it’s the hyphen. Not a dash. A bridge. A rebellion.

Color drains from Damian’s face, leaving behind a wax statue. He looks at the paper, then at me, mouth slightly open—a child just told magic isn’t real. Esther’s mask shatters with a sound only I can hear. Fury floods the space where magnanimity lived. Her manicured hands curl at her sides.

“What is the meaning of this?” she hisses.

“It’s a legally filed, state‑issued birth certificate,” I say. “I filed it two weeks ago.”

“You went behind our backs,” Damian stammers. There is disbelief in his voice. Also, the whine of a man who is shocked his chessboard has two sides.

“You were going behind mine,” I say, calm. “You and your mother decided to name my daughter after your ex‑girlfriend. You thought I wouldn’t notice? That I would smile and accept it?”

Silence pulls tight. Guests shift. Polite people do not know where to look when reality elbows its way into a curated room.

“You had no right,” Esther says, voice cracking on right. “The Ford name is not something you dilute with—your name.”

There it is. The confirmation that I am—and will always be, in their geometry—an outsider. The incubator for the next generation. The body, not the identity.

A clean, cold fury slots into place like a blade into a scabbard. I stand straighter. “I didn’t marry into this family to disappear,” I say, not loud but carrying. “Neither did my daughter.”

For a breathless beat nobody moves. Then Aunt Freya—fifty‑eight, quiet, kind, the one who brings lemon bars and leaves before the gossip curdles—steps forward. “Esther,” she says gently, “perhaps we should discuss this privately.”

Private discussions, in this family, are where the script is rewritten and you are told you misremembered your own lines. I am not interested in another rewrite.

“Lacy,” I say without taking my eyes off Damian. “We’re leaving.”

My sister is already moving, grabbing our coats, coiling fury into control. As we pass, she gifts Esther a look that could set silk on fire.

I walk down the hall past the family portraits—generations of men in tuxedos and women in chandelier earrings—and I do not look back. The door clicks behind us. The sound is the most satisfying thing I have ever heard.

On the driveway, I allow myself one glance through the big bay window. The party is a freeze‑frame of disarray. In the center, Kendall is not looking at me; she is turned toward Esther, mouth close to Esther’s ear. The smirk is gone. The look on her face is something like appraisal. In my head, I hear the words I imagine she’s saying in a voice that has practiced being listened to: Told you she’d bite.

Lacy drives. City lights smear into watercolor through the passenger window. My anger is no longer hot; it’s the kind that makes you very awake.

We do not go back to the Ford outpost masquerading as my home. We go to Lacy’s apartment—a small space that smells like lavender and drywall dust and autonomy. Isa is with my mother tonight, a blessed accident of planning. Lacy makes tea like she is throwing a life preserver.

“You know this isn’t just about a name,” she says finally, setting a mug down. “This was a power play. Esther’s been planning it for years.”

I think of the thousand paper cuts of being a Ford wife: the way Damian said the living room I decorated was “nice” but “not as timeless” as how Kendall arranged her parents’ house; the three‑inch binder Esther gave me for Christmas labeled FORD FAMILY TRADITIONS, complete with approved holiday menus and a section on how to address a thank‑you note without embarrassing the bloodline. Every page a test. My grade: incomplete.

“They’ve always been a unit,” Lacy continues. “Esther, Damian, and Kendall. It’s weird. There was some scandal back in high school—Esther smoothed it. My friend who went to school with them said Esther practically paid for Kendall’s first year of college. That bond goes beyond your husband.”

It lands like confirmation of a map I had pretended not to read. This wasn’t lingering affection. This was a strategic alliance, and I had been the imported vase—expensive, fragile, replaceable.

When I finally go home after midnight, the house is dark. The study lamp glows. Damian is elsewhere—his mother’s, the condo, a woman’s phone, I don’t care. The silence feels different: not empty; expectant.

I sit at his desk. The laptop is open, the screen asleep. I touch the trackpad; it wakes obediently. An email tab is open; my eyes scan the inbox: all the banalities of business, except—

Synced messages.

A thread with Kendall.

I click. The breath leaves my lungs the way a window opens in winter. Months of flirtation, inside jokes, and then, sliced into my life like a surgeon’s line, the confession: five weeks ago—the week I stayed with my mother because the doctor said bed rest or else.

Kendall: Your place is so much better without all her stuff. Damian told you it had potential. Make yourself at home.

Kendall again: Left a little something for you in your nightstand. See you tomorrow.

The small condo in the city. The one he kept for “late nights at the office.” The condo where she was nesting while I counted contractions alone and whispered please between breaths.

My grief flares into something cleaner. Purpose.

The desk is an heirloom—mahogany, heavy. I slide the bottom drawer shut too hard and hear a rattle. I drop to my knees, run fingertips along the inside. There: a notch. I press. A panel clicks. A thin compartment slides open.

Inside: a stack of letters tied with a ribbon the color of old bruises. Kendall’s script loops and flourishes; the ink is fresh.

Beneath the letters: a manila envelope. Unsealed. Family Law Offices of— I don’t need the name to know what it is. My eyes land on the title and everything inside me stills.

PETITION FOR DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE; REQUEST FOR SOLE LEGAL AND PHYSICAL CUSTODY OF MINOR CHILD.

Clipped to the back on a square of expensive stationery: two words in Esther’s precise hand.

Just in case.

In case I didn’t smile. In case I didn’t let them rename my child. In case I didn’t disappear.

I photograph everything. The custody draft. The note. The letters. The messages on the laptop. I become my own archivist, my own notary. Evidence is a kind of prayer.

I sleep three hours. In the morning, I make my first move.

I do not hit send all. I am not here for spectacle. I send three images, without comment, to two people: Tyron, the moral compass Esther calls a scold; and Aunt Freya, the woman who has always handed me a napkin instead of a complaint.

The lakehouse family gathering is the following weekend. I don’t go. Lacy’s friend who caters texts her from the kitchen like a Greek chorus.

Tyron arrives. He doesn’t let Damian monologue. He holds up his phone and says, calmly, “Do you have anything you want to say about Kendall?” It is not a question; it is mercy.

Damian blusters. Tyron shows him the photos. He shows them to anyone who will look. Voices rise. Esther moves in with condescension dipped in honey. Freya picks up her purse, tells Tyron, “I’ll drive,” and leaves. The room rearranges around the space where Esther’s authority used to be. Martina—Damian’s younger sister, twenty‑seven, Esther’s shadow since braces—watches with a look I have never seen on her face: calculation. Not cruelty. Calculation like a woman doing subtraction and finally, finally getting zero.

Two days later, the doorbell rings. I expect a storm. I get ice.

Kendall.

She looks furious in the way people look when their script is stolen: composed and empty of options. “You need to stop this,” she says, pushing at the door. I hold the frame.

“Stop what?” I ask. “Telling the truth?”

“You’re ruining everything.”

“They did that without me.”

“You have no idea what you’re messing with,” she says tightly, voice trembling. “This is bigger than you. Undo the damage now.”

I almost laugh at the audacity. “You think this is a game?” I ask. “You think I’m trying to win? I’m trying to live while you and your committee tried to annex my life.”

Her eyes flash. She leans in. “You don’t know what’s coming,” she says.

I meet her gaze. “Let me guess. A custody battle.” I don’t blink. “Don’t worry. I’ve seen the paperwork.”

For the first time, she goes still. Then she turns on her heel and leaves without slamming the door, and that unnerves me more than any threat. She’s not here to lose her temper; she’s here to measure mine.

For a week the house is a taut wire. Damian texts—Can we talk? and This has gone too far—and I do the kindest thing I can think of. I do not reply.

When the knock comes, it is measured. Damian stands on the porch looking like a man whose map has smudged. “I’m not here to fight,” he says, hands up. “Kendall is here. She wants to talk. We both do.”

Behind him, the dark hair. The cool assessment. I open the door and leave it propped. Not for them. For me. I won’t be trapped in the room I decorated while they write the new page.

We sit. They on the couch. Me in the chair opposite. A triangle. Geometry that suits me.

“I was never angry that you existed,” I tell Kendall before she can pivot. “I was angry that you believed—correctly—that I would be asked to live in the second row of my own life. I was angry that you all thought you could name my child like a placeholder.”

“This was never about second,” she says, voice flat, eyes sharp. “It was about securing the family legacy.”

Damian shifts—“Kendall, maybe we don’t—”

“She started this,” Kendall says without looking at him. “She deserves to know what’s at stake.” Then she sets her hand on her stomach with a theatricality I might admire onstage. “I’m pregnant.”

Of course.

“It’s Damian’s,” she adds, pretending there’s any doubt left in the galaxy.

A year ago this would have shattered me. Now it clarifies. The urgency. The documents. The name.

“So that’s the plan,” I say. “Replace the disobedient wife and baby with a compliant model and a child named correctly on the first try.”

“It’s not about replacement,” Kendall says, and for the first time there’s fatigue in her voice. “It’s about tradition. Legacy. Something you’ve never understood.”

I smile—a slow, cold thing. “You’re right. I don’t understand trading law for tradition.” I lean forward. “You forgot something in your little empire plan. You were so busy being the past that you forgot the present is written in ink.”

She blinks.

“You were so focused on being Esther’s daughter,” I say to her, then turn to Damian, “and on her being your whatever that you made her your mistress. I was the one you married. I am the one on the mortgage, the insurance, the taxes. In this state that makes me your legal partner. Half of everything you think is yours is… ours.”

Damian’s face drains. It’s not money that scares him; it’s consequence.

Kendall stands. The mask cracks. “You can’t do this.”

“I already did,” I say, and open the door.

They leave. Two days later a courier arrives with an envelope heavy enough to bruise: an emergency injunction filed by Esther on behalf of her son, questioning the paternity of my child. Of course. When you cannot own something, you deny it exists.

Lucas reads, sighs, and says, “It’s malicious and baseless, but a judge will order a test just to shut the door. Are you okay with that?”

“Let them pay for it,” I say. “Let them feel the price of their fantasies.”

The lab is cold. The swabs brush cheeks; the forms collect signatures; the machine does what machines do without caring about anyone’s version of legacy. A week later, the judge—a woman in her late fifties with short hair and the square shoulders of someone who has carried more than one burden—looks at the paper and then at Damian and then at Esther.

“The results confirm Mr. Ford is the biological father,” she says. Her tone is not unkind. “As for the child’s registered name, the birth certificate was filed legally and properly by the child’s mother within the mandated time frame. There are no grounds to amend it without the consent of both parents.”

Esther stiffens. Damian stares at his shoes. Lucas clears his throat. “Your Honor, there is one additional matter,” he says. “A sworn statement from Ms. Freya Lucas attesting that Ms. Kendall Bell was present at Mr. Ford’s private condominium on multiple occasions during the final weeks of Ms. Fuller‑Ford’s high‑risk pregnancy.”

“It’s irrelevant to the legal questions before the court,” the judge says. “It is, however, relevant to my opinion of everyone’s character.” She taps the file. “Petition dismissed.”

It is over.

In the hallway, Esther is already gone, trailing perfume and unspent rage. Damian stands there like a man whose team forgot to tell him the rules changed three seasons ago.

“You let them do this,” I say, not raising my voice. “You let them rename our child at a party, question her existence in court, turn our life into a performance of someone else’s tradition.” I pull a new envelope from my bag. Not a draft. The thing itself. “This is your tradition now,” I say. “Losing the things that mattered because you couldn’t find your spine.”

The divorce papers click into his hand. His fingers close around them reflexively. His mouth opens. I walk away.

I am not interested in hearing the sound a Ford makes when the Ford smile breaks.

Part Two

Relief is not joy. It’s exhale. It’s a room that stops humming. It’s sleep that lasts more than two hours in a row. For the first time in months, I have all three.

I am making space where things used to live. The nursery I painted with my colors—sea‑glass and soft greens—feels like a place that belongs to life, not performance. Isa naps in a sunbeam like a cat everyone loves. At three a.m., when she cries, there is no flinch of fear that someone will weaponize my exhaustion. There is just us.

The Fords, it turns out, are not weatherproof.

Lucas calls from a number he only uses when the news is too good to fit in a text. “You’re not going to believe this,” he says. “I just got off the phone with a colleague at the state revenue department. Someone filed an anonymous tip alleging irregularities in a Ford family trust—Esther’s trust. Very specific irregularities.”

The word specific is doing a lot of heavy lifting. I picture Martina’s face at the lakehouse—the way she watched instead of defending. Lacy’s rumor surfaces: Esther “smoothing” Kendall’s education. Lucas goes on. “Funds designated for education and welfare allegedly funneled to a third party for years—tuition, apartments, cars. Account numbers. Transfer dates. They’ve opened a full audit.”

“Martina,” I say. It comes out as a breath and a prayer. The overlooked daughter with a front‑row seat to a matriarch’s hypocrisy finally found a lever she could pull without being crushed beneath it.

“Whoever it was,” Lucas says, “just put a crack in a foundation that’s been painted over for decades.”

The audit takes months. That’s the nature of audits and myths: they both unravel slowly. But when it finishes, the numbers are simple and brutal. Esther is ordered to repay nearly two decades of unauthorized distributions, with interest and penalties. The lakehouse sells. So does a chunk of the portfolio that bought the cream‑and‑gold and the catered holidays. The trust—allegedly for “family” and “legacy”—turns out to have been a conduit for a single, carefully chosen outsider.

Kendall stays long enough to negotiate child support and then leaves a state where her name now tastes like metal.

I don’t gloat. Not because I am better. Because I am busy.

A week after the audit news becomes a whisper everyone knows, Isa turns one. The cake is a cheerful disaster of pink frosting, sprinkles, and enthusiastic palms. My apartment smells like sugar and coffee. Lacy snaps photos from the floor like a sports photographer. I laugh a laugh that has nothing to do with performance and everything to do with the small person waving a frosting‑covered hand as if directing an orchestra.

“Speaking of demolition,” Lacy says, swiping a smear of pink off my cheek with her thumb, “Tyron called. Final numbers are in. It’s not just the money. They finally talk to each other like people, not staff.”

I picture Aunt Freya at her kitchen table, lemon bars cooling, saying, “Martina, do you want to drive with me to the coast?” I picture Martina saying yes.

My phone buzzes with a message from Freya: a photo of a sunset properly named—gold that isn’t cream. We are okay, the caption reads. There is no mention of Esther or legacy. The thread between us hums with a different word: enough.

The divorce takes exactly as long as it takes a man like Damian to realize the law is not an opinion. His lawyer postures. Mine produces the paper that matters. I am reasonable. I am also done.

He tries for reconciliation once—flowers in hand, apology in the middle distance. He says words about second chances. I tell him my second chance is the life I’m already living. The door closes. The lock turns. The silence afterward is not ice; it is wool. Soft. Warm. Mine.

On his weekends with Isa he tries to be the sitcom version of a father: trips to the park that last exactly the length of the timer on his phone; pictures forwarded to Esther; questions asked like items on a checklist. At first, his distance angers me. Then it worries me. Then it becomes another thing I cannot fix that doesn’t need to be mine to carry. I write a list of things I can do—pack snacks, send a sweater even if the forecast says sixty—but loving a person into good fatherhood is not on the list. I cross it off anyway, in my head, for the girl who still tries to pass tests nobody told her about.

There’s one more tradition I let go of like a helium balloon: the Ford family gathering. They still have them, smaller, hungrier, more careful. I am not invited. I don’t want to be. If you can imagine a room without yourself and feel your chest expand, that is the direction to walk.

I build other rooms. The community art space gets a second set of shelves for supplies. We start a grant program for teen moms who want to take classes without choosing between paint and diapers. On Thursdays we host a drop‑in poetry night where ninth graders write lines that hit me like prayer blindsiding a cynic. We hang their poems next to their collages and under them I tape little labels that say ARTIST: ISA’S MOM because sometimes a child needs to see her mother’s name under something beautiful.

I still see Lucas, mostly for coffee and occasional document emergencies, sometimes because we like the same bakery with the lemon bars that taste suspiciously like Freya’s. Lacy, of course, sees herself in my front door like an eclipse sees daylight.

On a Tuesday that looks like every other Tuesday, an envelope arrives. Not thick. Not threatening. Plain white. Inside: a card with a watercolor of lilacs. My mother’s handwriting, familiar and foreign, curls across the page.

We found an old apron in the hall closet. The one you wore when you baked with Grandma. Do you want it? —Esther

It is not an apology. It is an offer. Some apologies arrive wrapped in declarations. Some arrive wrapped in flour dust.

I tell her yes. She leaves the package in the lobby with my name printed too carefully, as if names could be correct if you held your breath long enough. The apron smells faintly of vanilla and time. I put it on and make a cake because I can. I cut a slice before anyone else comes home. I eat it standing up.

A text pings from an unknown number. Martina: I’m sorry for what you went through. I didn’t know how to help before. I’m trying better now. I reply with a single heart. We are not friends. We are women whose maps intersected, briefly, at the same sinkhole.

The photo that once sat in the heavy frame on Esther’s mantle—the one where families dress in navy and pretend they never eat—is now tucked into a box under my bed, face down. On the wall of my living room hangs a different picture: me, hair up and paint‑splattered, surrounded by kids holding brushes like wands, all of us mid‑laugh. A nine‑year‑old took it on a disposable camera and scrawled on the back MISS ROBIN IS COOL in pencil with such pressure the letters are embossed. That is the portrait I choose.

When Isa is old enough to ask about her name, I will tell her what names can be: gift, anchor, tool. I will tell her how the paper that held hers felt heavy, like armor, and how the day I unfolded it across a table my hand did not shake. I will tell her that some people believe legacy is something you inherit; others know legacy is something you make, one choice at a time. I will tell her that Marin was a woman who raised three children alone and taught me to thread a needle by the light of a kitchen window; that Fuller is a name that means “the one who made,” and Ford is a name that means “crossing place,” and that on the day she was born I decided we would be both—makers and crossers.

When she is older still, I will take her to the registrar’s office and show her the counter where I wrote her name, so that when someone tries to take something from her with a smile, she will know she can take it back with ink.

If I’m lucky, by then she will be bored by the story. She will roll her eyes at the part where her grandmother tried to change her name at a party. She will look up from her book and say, “Mom, can we get ice cream?” And we will. We will go to the shop with the chalkboard menu and the owner who gives kids tiny cones for free and the bench with the carved hearts that have outlasted the couples who carved them.

On the way home she will fall asleep in her car seat and I will carry her upstairs and tuck her in and take off the apron and hang it on a hook and stand in the doorway for a moment doing nothing but listening to a small person breathe.

And I will think—not triumphantly, not cruelly—but with a quiet that feels like a room I own: Let them keep their traditions if they like. I kept the only one that matters.

I named her with love.

And that love carries my name.

END!

News

My aunt’s inheritance gave me a house and two million dollars. Out of nowhere, my parents—who hadn’t been in my life for 15 years—appeared at the will reading, saying, “We’re your guardians.” When my lawyer stepped in, their faces drained of color. Ch2

Yesterday, at 28 years old, I became a millionaire. My Aunt Vivien, the woman who raised me, left me everything:…

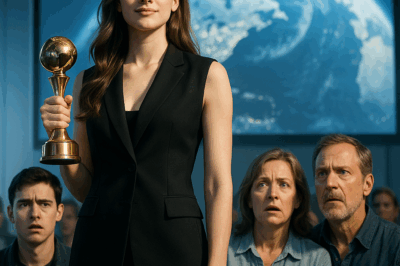

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

My ex-husbamd bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… CH2

My ex-husband bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… Part One My…

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… CH2

My ex-husband’s mother told me to leave ASAP when I got a divorce, but she regretted it later… Part One…

After my dad’s funeral, my SIL suddenly said the inheritance goes to her husband. I was stunned… CH2

After my dad’s funeral, my SIL suddenly said the inheritance goes to her husband. I was stunned… Part One I’m…

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so i left in silence. Then they started panicking… CH2

My husband and daughter ignored me forever, so I left in silence. Then they started panicking… Part One My name…

End of content

No more pages to load