Mom Told Me, “You’ll Never Be As Good as Your Brother.” So I Proved Her Wrong in the Best Way.

Part 1

I grew up in a house where pride had a preferred direction. It ran like a current toward my brother and away from me, sloshing a little in my direction only when it overflowed his shores. He was the golden child—Luke—with his clean jawline and cleaner report cards, captain of this and president of that, his name printed beneath photographs that were framed and dusted and pointed out when company came. I lived in the negative space: the one behind the camera at birthday parties, the feet cut off at the edge of the family Christmas card, the helper, the holder, the one with “potential” that arrived like a threat and never like a gift.

Mom didn’t mean to be cruel, I used to tell myself. She was just efficient with her praise. Why spread it evenly when one child had a trophy shelf that bowed under the weight and the other had… what? Sketchbooks? Early drafts? The faint smell of acrylic on her fingers and the stubborn habit of daydreaming during dinner? She loved me, I told myself, in a general way. But she loved Luke in a way that made lists and announcements and casseroles for booster club fundraisers. Her love for him had nouns.

When I was ten, I won a small poetry contest for a shaky little thing I wrote about the sound of the dishwasher and the way the water sparkled like applause. I came home, paper in hand, cheeks hot with the kind of joy that doesn’t know it’s small. Mom looked up from stuffing envelopes for Luke’s baseball banquet and said, “That’s nice, Hannah. Put it on the fridge.” There was no space on the fridge. It had been colonized by Luke’s schedules, Luke’s ticket stubs, Luke’s face in a glossy team photo. I wedged my poem under a magnet shaped like a lemon. It hung crooked for a week and then disappeared. I found it later in the junk drawer, soft at the corners from bumping into rubber bands and disposable lighters.

So I learned to stop bringing my little wins to a room that kept measuring them against a different ruler. I learned to be the person who passes the ball down the table and doesn’t mind if her plate arrives last. I learned how to clap without envying the person taking the bow, and I learned how to survive inside a silence that wasn’t mine.

And then one day, Mom stopped being subtle.

It happened on a Wednesday, the kind that was already tired by lunch. I had called to tell her something I was—for once—proud of. I’d landed a part in a local theater production—a role with real lines, breathing room, a small arc that felt like it matched the one I was trying to draw inside myself. It was my first big yes in years. I wanted, with the aching hunger of a person who remembers hunger, for her to say I see you. I wanted her to reduce the distance between love and proof.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said, and the words were so light they might have floated if they hadn’t been carrying a barb. “You’ll never be as good as your brother.”

There it was. Not an implication. Not an eye roll. A verdict, stamped and filed and placed in the cabinet where she kept truths she didn’t intend to revisit.

If you asked me, later, how I responded, I couldn’t tell you. I don’t think I did. There are moments so final they make conversation an insult. I remember nodding into the phone like a person agreeing to a price she doesn’t intend to pay. I remember setting the phone down on the kitchen counter, the edge of it pressing a small, precise line into my palm. I remember standing very still, as if motion would make the words spread. But here is the thing I remember most clearly: I didn’t feel sad. Not first. I felt… heat. Clean and exact. A coal in the center of my chest that glowed with its own decision.

Anger, yes—but braided with something better. Determination. Not the showy kind, not the vow you make out loud and then abandon when the world complains. A private promise. A quiet recalibration of the universe I could control: I will no longer audition for a role in a story that hurts me.

That night I stared at the hairline crack in my ceiling and took inventory. How many doors had I not knocked on because I could hear her voice on the other side? How many choices had I made by asking, Will she approve? before asking, Will I be alive there? How many times had I tried to wear my brother’s shoes and then felt stupid for tripping?

I had been living inside a comparison so constant it felt like climate. Luke’s path had been well-lit and narrow: sports, academics, leadership. My path had been a wider thing, messy and less flattering in photographs: writing, acting, painting, staying after rehearsal to help paint flats, crying over one sentence until it rang true, mixing a green that wasn’t on the palette. I had spent so much time apologizing for my map that I had never learned its roads.

The next morning, I made coffee that tasted like a dare and wrote a contract with myself in a cheap notebook: No more asking permission to be the person you already are. It would be okay if it took time. It would be okay if it didn’t look impressive on a mantel. It would not be okay if I shrank to fit a frame that had never been designed for me.

I started small. I bought pens that moved without catching. I wrote every morning, even when the sentences sounded like wooden shoes. I took a six‑week scene study class above a laundromat where the radiators clanked like percussion and the teacher, a woman named Mara who had worked with just enough famous names to be irritating and exactly enough kids like me to be holy, told us, “Say the truth and let the world make room.” I stretched the canvas I’d hidden in my closet behind winter boots and let color do the talking my throat was tired of.

It wasn’t glamorous. I poured lattes in the mornings for people who said their names slowly as if they were worth more ink than mine. I wiped tables and I wiped tears. I learned to take rejection with a nod and a calendar, marking the day I would try again. I learned to hear the voice that said, You’ll never— and answer, Watch me.

But dabbling wasn’t going to rewrite anything. I could sense that. If I wanted to pry the story open from the inside, I’d need to do something louder than a well‑delivered monologue or a neat little painting hung in a hallway. I wanted a work that would point at itself in a room and leave even my mother with nothing to say. I wanted to build a stage and then set myself on it and then invite everyone who had ever cut me out of the frame and then… not flinch.

So I set a goal so audacious it made me laugh when I wrote it: Write, direct, and produce your own play.

It sounds arrogant. It wasn’t. It was survival disguised as art. I had spent a lifetime living in rooms other people designed; I wanted to build one that held me without apology.

The play started as an image: two siblings standing in a house made entirely of mirrors—one multiplies, the other disappears. I wrote at the bar after my shift with the espresso machine still warm behind me. I wrote on the bus and I wrote on my break and I wrote in the few generous hours after midnight when the city quiets enough to hear your own pulse. The first draft was a mess. The second draft was a mess but less proud of it. The third draft had a voice I recognized. I titled it Shadow Work because sometimes honesty refuses to be subtle.

I scraped together a budget the way you build a bird’s nest: one found thing at a time. A mini‑grant from the arts council paid for rehearsal space and tiny stipends. I designed the poster myself: a silhouette backed by a floodlight, the tagline “Come see the person you keep missing.” I taped them in coffee shops and libraries and the kind of bars that cultivate a reputation for saying yes to strange beauty. I made a spreadsheet that would have made my brother proud and a to‑do list that made me dizzy.

And then people began to arrive.

Maya auditioned for the lead—a part that could have eaten a lesser actor. She read my words like she’d been living them in her mouth for years. Jonas, a gentle baritone with a soft spot for underdogs, auditioned for the brother and then asked if he could also run sound because “I like the way plays feel when everything clicks.” Priya, a stage manager whose checklists had checklists, appeared at the first rehearsal with color‑coded binders and a bag of clementines. Zed, a lighting designer who spoke in metaphors and lumens, stood in the theater on a dark afternoon and murmured, “Let’s make absence visible.”

We met on weeknights in a black box theater that smelled like sawdust and old applause. We taped the floor and taped our hearts and promised to tell the truth in a way that didn’t require anyone else’s permission. We rehearsed scenes where the mother says the quiet part out loud, and Maya would look at me after and ask softly, “Does it feel like it?” and I would say yes and no, because the thing about art is that it makes exactness out of the approximate.

Obstacles arrived right on time. Our original venue double‑booked and “regretted the inconvenience.” Mara let us use her studio for a week while I negotiated with a different theater manager named Gus who wore flannel year‑round and believed in first‑time directors “because somebody did for me in ’93.” Two weeks before tech, our actor playing the father booked a commercial and dropped out. I made a list of men who could memorize in ten days and found one who had been waiting for precisely this kind of rescue. The grant funds stretched thinner than honesty; I started saying please to people I had spent years not wanting to owe. I discovered that collaboration is the art of owing each other on purpose.

Every time I hovered near quitting, Mom’s sentence replayed with the stubbornness of a song you hate. You’ll never be as good as your brother. Good, I decided, is a wild word. It needs to be interrogated. Good by whose measure? Good for what? Good to whom? I didn’t want her good anymore. I wanted mine.

The week of opening night arrived like weather. We printed programs on recycled paper with ink that smudged if your hands were nervous. We hung cheap curtains and made them look expensive with light. I borrowed a steamer from a friend who said, “Don’t put your face too close,” and I put my face too close and yelped and Jonas made fun of me until love replaced pain. I ate pretzels for dinner and called it a superstition.

The morning of the premiere, I woke to a text from an old neighbor: Your mom’s been telling the ladies at church you have a show tonight. She’s “curious” to see it. Curious. The word made me both nauseous and oddly exhilarated. I hadn’t invited her. I hadn’t invited anyone from that old house. But word is a river; it finds its own course. Part of me hoped she wouldn’t come; part of me—if I am brave enough to admit it—wanted her to be in the room when I stepped out of the shadow and onto a stage I built with my own tired hands.

Call time was seven. At six‑thirty, I stood in the back of the house and watched strangers fill seats. There is no drug like that: all those bodies choosing to share a breath with your idea. I recognized bar regulars and the woman who sells me thread at the fabric store and my coworker’s dad who attended everything labeled “art” like he had taken a personal oath. I saw Luke slip in near the aisle, his hair a little longer than last time, his face softer. He waved, small and private, and I waved back. And then I saw her.

Back row. Arms crossed. Pearl earrings that could unfasten an entire room. Expression unreadable as a closed book.

My heart pounded once, hard, and then settled. This wasn’t about her. This wasn’t about him. This was about me and a work that had required more of me than any person ever had. I took a breath Mara had taught me—fill from the bottom, let it climb the spine—and walked backstage.

The last five minutes before a show are made of electricity and superstition. Priya tied and retied a knot in her sweatshirt drawstring. Maya whispered, “You wrote me out of a corner I didn’t know how to leave.” Jonas squeezed my shoulder and said, “We’re ready,” and I believed him because he always only said things when they were true. I checked the props table like a pilgrim. Zed called “House out,” and the room exhaled.

Lights down. The audience hushed in that involuntary, beautiful way crowds do when they know something is about to happen that didn’t exist five seconds ago.

We began.

In the first scene, the siblings stood side by side and counted the ways a person can disappear while standing in plain view. In the second, the mother praised the boy for breathing and told the girl she was “so creative” in the tone you use for a child who has drawn on the wall. In the third, the girl built a door with her hands and walked through it. The audience leaned forward, not dramatically, but like wheat in a wind. Laughter arrived in exactly the right places—small, grateful, not cruel. Silence arrived in the other places—respectful, prickly, generous. When Maya said the line, “I will not audition for pain,” I heard someone in the second row whisper, “Oh.”

At the halfway mark, a light cue misfired and flooded the stage too soon. Zed fixed it mid‑breath. In the quiet scene before the end, the brother sat on the floor and admitted that being loved like the sun was not the same as being warm. You could feel the air change. The last monologue landed in the center of the room like a small bell. Then light, then darkness, then applause.

Thunder. Not polite clapping. Not the kind of applause people give because they paid for a sitter and want to validate themselves. The kind that rises in the body before the hands catch up. The kind that says, We heard you.

I stood for the curtain call with my cast arranged like a sentence whose grammar had finally, finally, made sense. We bowed. We straightened. I stepped forward when they pushed me forward and I caught my mother’s eye. For the first time in my life, her expression didn’t feel like a test. Something moved there—pride, maybe, or a grief that arrived too late to be useful but not too late to be honest.

The curtain fell. We rushed into the small, bright backstage where congratulations crash around like happy furniture. Priya cried into my shoulder; I cried into hers. Mara appeared with flowers she had obviously purchased at intermission and said, “You built a room that fits you.” Gus slapped my back and told me a story about his first show that made me love the year 1993. Strangers said sentences that grew the night bigger: “I felt seen,” “That was my mother,” “I didn’t know you could tell it like that.”

And then I noticed her. Mom stood at the threshold of the backstage hallway as if unsure whether the word welcome applied to her. The confidence she wore like a coat had slipped off one shoulder. For a second, neither of us moved. She looked smaller than the verdict she had delivered to me months earlier. She looked like a person and not like a wall.

“Can we talk?” she asked. Her voice had misplaced its edge.

I nodded. We stepped out into the alley behind the theater where the night air felt cool enough to be kind. The door thunked shut behind us, muting the celebration into a warm hum—a proof that joy could continue without us and would be waiting when we returned.

She looked at her hands. Then at the amber halo around the streetlight. Then at me.

“Your play,” she said, and stopped, and tried again. “Your play was… incredible. I had no idea you were capable of something like that.”

The compliment landed like a coin tossed too late in a fountain. It glittered, even as it made a wish ache. I felt validation and sadness and relief and none of the old, feverish hope. I had built a world that didn’t require her permission to exist. I could accept her sentence without needing to be sentenced by it.

“Thank you,” I said. I didn’t demand an apology. I didn’t offer one. The breeze found my hair and lifted it and set it back down like blessing.

She took a breath that sounded like a hinge.

“I realized something tonight,” she said, and the vulnerability in her tone startled us both. “I spent so many years putting your brother on a pedestal, sure his path was the only path that mattered. Watching your play… it made me see how wrong I was. Success isn’t trophies or titles. It’s… this. Passion that leaves a mark. You’ve done that.”

Some part of me that had been waiting at a door for decades finally stood up and left. I’d thought proving her wrong would feel like fireworks; instead it felt like rearranging furniture and finally being able to walk across a room without bruising your shins. Warm. Practical. True.

Back inside, the cast whooped when they saw me. Luke found me near the prop shelf and wrapped me in a hug that belonged to the kind version of our childhood, the one we had sometimes managed when the house went quiet. “I had no idea,” he said into my hair, and then held me at arm’s length. “I mean, I knew you were you, but this… Hannah.”

I laughed—real, round laughter that made the back of my neck go warm. For once, I didn’t feel like I was catching up to a train already moving. I felt like I had arrived at a station I had built.

We stayed late enough to be in the way and early enough to leave the staff with a chance to close without resenting us. I signed two programs and a playbill someone had stolen from the front row. I swept confetti someone had snuck in and scattered at the end. I sat for a minute alone in the dark house while the sound of the city came in faint through the exit signs and realized that I had managed, for a breath, to stand outside comparison and simply be.

What happened next, I couldn’t have predicted. I thought the best part of the night had already happened. I thought the twist was the simple fact of my mother’s face rearranging itself around a new truth. But life, as it turns out, is a better playwright than I am.

Two days later, an email arrived that would turn the small room we’d built into a door we hadn’t known was there.

—To be continued in Part 2.

Mom Told Me, “You’ll Never Be As Good as Your Brother.” So I Proved Her Wrong in the Best Way.

Part 2

Two mornings after the premiere, my phone buzzed with an email notification. I was still in pajamas, sipping coffee that tasted faintly of cardboard because I’d reused the filter, when I opened it. The subject line read: Invitation from the State Arts Festival.

For a second, I thought it was spam—some mailing list I’d accidentally landed on when I bought discount brushes. But then I read:

“Dear Hannah, we were in the audience for your debut of Shadow Work. We would like to extend an invitation for you to bring your play to the State Arts Festival this summer. Your voice is fresh, urgent, and necessary. We believe more people need to see what you’ve created.”

I stared at the screen until my coffee went cold. My little play—the one I had pieced together with duct tape and favors, in a theater that smelled like wet wood and old lights—was being invited to a festival where people paid for tickets, where critics scribbled in notebooks, where real directors scouted for new work.

I called Mara first. She whooped so loud the line crackled. “See? See? I told you. Truth makes a room.”

Then I called Jonas. He said, “I’m in. Just tell me when. I’ll quit my job if I have to.” Priya texted back in all caps: TELL ME YOU’RE SERIOUS. Zed just sent a string of light bulb emojis, which, from him, was basically Shakespeare.

I sat back on the couch, letter open, heart doing cartwheels. And then I thought of Mom.

She called me that evening.

“I heard about the invitation,” she said, her voice quieter than usual, like she was standing at the edge of something. “Congratulations.”

“Thanks,” I said carefully.

Pause. “Your brother never got asked to something like that.”

The words might once have been a dagger. Tonight they sounded more like surrender.

“Maybe because it wasn’t his path,” I said. “This one’s mine.”

She didn’t argue. For once, she just let the silence be.

The months leading up to the festival were chaos and magic in equal measure. We tightened the script, added new lighting cues, stitched costumes that didn’t fall apart mid-scene. I worked part-time at the café to keep afloat, then rushed to rehearsal, my notebook scribbled with revisions and my soul scribbled with nerves.

There were days when exhaustion pressed so hard I thought maybe Mom had been right all along. Maybe Luke’s clean, linear path was the only safe one. But then I’d watch Maya deliver the final monologue with tears sliding down her face, or hear Jonas whisper the brother’s confession in the dark, and I’d remember: I had built this. We had built this.

Opening night at the festival arrived like a thunderstorm—loud, electric, impossible to ignore. The theater was twice the size of our black box, the seats plush instead of threadbare. I peeked from backstage and saw rows filled with strangers, a few local critics, even a city council member whose name people said like it mattered. And there, near the middle, sat Luke. And next to him, unbelievably, Mom.

My chest tightened, but this time not from fear. From readiness.

The play unfolded like it had been waiting for this stage. Every line landed, every pause hummed. The laughter was louder, the silences deeper. When Maya delivered “I will not audition for pain,” someone in the audience gasped audibly. At the end, the applause wasn’t just applause. It was a roar.

We bowed, cast linked arm in arm, and the lights washed over us like blessing. I scanned the audience one more time. Mom was on her feet. Clapping. Not politely. Not reluctantly. Fully.

Backstage, Luke found me first. “Hannah,” he said, gripping my shoulders. “You were brilliant. I wish I’d had half your guts.” His eyes were bright, and for the first time, I saw not competition, not hierarchy—just my brother. My equal.

Mom approached slower. Her face was complicated: pride, regret, maybe fear of saying the wrong thing. Finally, she spoke. “You proved me wrong.” Her voice broke. “And thank God you did.”

I didn’t rush to hug her. I didn’t collapse into tears. I simply nodded. “I know.”

Because I did know. I didn’t need her words anymore. But hearing them was like closing a door gently instead of slamming it.

In the weeks after the festival, reviews trickled in. Words like raw, vulnerable, necessary appeared in print beside my name. The theater offered me a residency for new work. A college professor emailed, asking if he could teach Shadow Work in his seminar on identity and art.

But the best moment was smaller. Josie—the girl in the front row with braces and bitten nails—sent me a handwritten note through the theater office. “I thought I was the only one who felt like the extra sibling. Thank you for making me feel less alone.”

I pinned it above my desk. That was the trophy I hadn’t known I wanted.

Mom started calling more. Not to compare, not to measure. Just to ask: “What are you working on? When can I see it?” It wasn’t perfect. The years of imbalance couldn’t be erased. But I didn’t need them erased anymore. I had outgrown the frame.

Luke and I grew closer, too. We joked about trading titles: he could be the golden boy, and I could be the shining girl. One night he admitted, “You know, being ‘the best’ all the time felt like a cage. I envied you, actually. You got to find yourself without everyone watching.”

I laughed at the irony, but later, in bed, I thought: maybe both of us had been shadows. Just in different ways.

Looking back now, I don’t regret her words. They hurt, yes. They scarred. But they also lit a fire I might never have found otherwise. That sentence—You’ll never be as good as your brother—became the push that made me discover something truer:

I was never supposed to be.

I wasn’t Luke. I was me. And being me turned out to be more than enough.

The last night of the festival, the cast gathered in the empty theater. We sat on the stage, legs dangling, eating greasy pizza out of the box. We told stories about the mistakes that had turned into miracles, the cues that almost killed us, the lines that had healed us.

I looked around at the faces—my people, my room, my light—and thought: This is better than trophies. Better than pedestals. Better than approval. This is mine.

For the first time, the shadow I had lived in so long didn’t feel heavy. It felt like contrast. The kind you need to make the light brighter.

And that was how I proved her wrong—not by becoming my brother, but by becoming myself.

The End

News

My Dad Told My Son, “If You Want to Eat, Go Find a Dumpster.” Mom Laughed. So I Threw Out Everything. CH2

My Dad Told My Son, “If You Want to Eat, Go Find a Dumpster.” Mom Laughed. So I Threw Out…

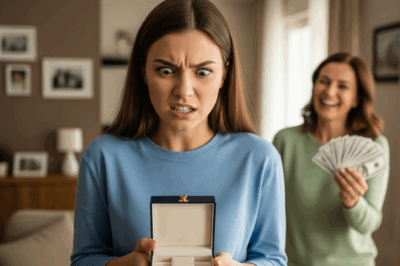

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever. CH2

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever Part One The…

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off. CH2

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off Part…

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside. CH2

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside Part…

After 9 Years, Couple Opens Wedding Gift Aunt Told Them Not To Open. CH2

Part 1 They married in late spring, on a day that seemed made of warm light and second chances. Kathy…

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sisters Wedding So I Took Revenge. CH2

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sister’s Wedding So I Took…

End of content

No more pages to load