They beat me with a belt for refusing to serve his adult son like a maid. “Feed him or get out,” my mom spat. I walked out with a broken arm, one dollar, and no toothbrush—and they never called. But in this family drama, they forgot one thing: I was already building something that would change everything.

Part 1

Dinner used to be the only time I could pretend we were a family.

For fifteen minutes, I could focus on plates and cutlery, lining up silverware like soldiers, hoping that just once no one would raise a voice, that maybe Mom would smile or Greg would keep his belt on. That night I set the table in silence. The air smelled of reheated pot roast—bland, heavy. I polished the forks, folded the napkins, even lit a cheap tealight from the dollar bin. Maybe peace could be coaxed by small efforts.

Greg collapsed into his usual chair like he owned the oxygen. His son, Carter—eight years old, legs swinging under the table—was already barking orders like a prince with a plastic crown.

“Juice,” he said without looking at me.

I poured apple juice, hands steady, jaw tight.

“He likes it with ice,” Greg muttered.

I turned to the freezer. When I set the glass down, Carter sighed. “Too slow.” He slurped, then tossed his fork onto the floor. “Oops,” he said, eyes on me.

I bent for it, knees aching against the linoleum. When I rose, I glanced at Mom; she was still scrolling her phone.

I placed the fork beside Carter’s plate and reached for my chair. I had just felt the edge of the seat under me when Mom’s voice cut the air like a slap.

“He eats first. Then you clean up. He’s the king. You know your place.”

I froze, then sat anyway—just for a second. I was hungry, too.

Greg’s head lifted slowly. “What did she just do?”

“She sat,” Carter laughed.

Greg slammed his own fork down. “Did I say she could sit?”

My mouth opened; nothing came. I stood. The look in his eyes—the one that always came before the belt—darkened. Juice clinked in Carter’s glass.

“Juice,” Carter barked again.

I reached for the pitcher. His glass was still full.

“He hasn’t even finished,” I said.

Greg scraped his chair back. “I said, serve him.”

“He has arms,” I said, the sentence surprising even me. “He can serve himself.”

Silence fell like a blanket smothering a flame. Greg’s hand moved to his waist. Leather slid through denim loops with a sound that turned my stomach to stone.

“Say it again,” he said, stepping toward me.

I didn’t. I held my breath and my place.

The first hit lashed across my upper arm; the second burned my back. I screamed. “Greg—stop!” But Mom didn’t move. She stepped close enough for her perfume to sting and grabbed my face so hard her nails broke skin.

“You feed him,” she hissed. “Or you get out, worthless girl.”

The belt cracked again. Carter laughed. The kitchen spun. Pain pulsed through my shoulder in sick waves; my right arm hung wrong, numb and hot. Mom’s finger stabbed toward the door.

“Out,” she said. “You heard me.”

Greg yanked open the front door, satisfied. “You want to act grown? Then leave.”

Barefoot in a sleep shirt and thin pajama pants, I moved to the hall. My wallet on the counter—empty. I checked my hoodie pocket. One wrinkled dollar bill. That was it.

“Toothbrush?” I asked, voice so small it made me flinch.

The door closed hard enough to rattle the pictures. The deadbolt turned with a click that echoed louder than the belt.

I stood on the porch in the porchlight’s uncertain cone, cradling my arm. The concrete burned my feet. Somewhere down the street a dog barked, then stopped. I took one breath, then another, then stepped off the porch and limped down the driveway—no bag, no shoes, no goodbyes. One broken arm and one dollar.

Half a block away, a streetlight buzzed, flickered once, then steadied. I sat under it, my back against the pole. Warm trickles of blood slid from my temple into my hairline. I didn’t wipe them. I looked at my scraped hands—small, trembling—and said to the dark, “I’m still here.” The words didn’t feel like triumph. They felt like a plan.

Downtown Bakersfield at midnight doesn’t offer mercy. Shops were shuttered. Neon signs blinked with the tiredness of the overworked. I passed a boarded-up diner whose faded letters still promised BREAKFAST ALL DAY. A church door was locked; even its silence felt tired. At a gas station the fluorescent lights flattened color into an interrogation.

“Bathrooms are for paying customers,” the clerk said without looking up.

“I have a dollar,” I said.

“Water’s eighty-nine cents.”

I brought a tiny bottle to the counter. “No bag,” I told him. The bathroom mirror showed a swelling eye and a bruise blooming along my cheekbone like a storm on a satellite map. Dry blood streaked my neck. The way my arm hung made my stomach lurch.

“This,” I whispered to the mirror, “is what worthless looks like to them.” But the mirror didn’t answer, and that felt… right somehow. Worthless wasn’t a face. It was a sentence somebody else wrote.

I found a bench near a bus stop under a billboard for INJURY LAWYERS with a number so large it made me want to laugh. I must have slept; I woke to a voice as worn as the sidewalk.

“You hungry, baby?”

A man stood a few feet away, older, skin the color of good earth, wearing a navy coat gone soft at the elbows. He carried a rolled blanket and a brown paper bag. He didn’t come closer. He sat slowly, knees complaining softly.

He tore a sandwich in half, handed me the bigger piece. “Don’t got to take it,” he said. “But ain’t no harm in offering.”

“Thank you,” I managed.

“Name’s Elijah Burke,” he said after a while. “Most folks call me Mr. Elijah on a good day. Old man Elijah on the others.”

“Kalin,” I said. The way I said it sounded like a dare and a prayer at the same time.

He nodded. “Well now,” he said, “I know who to pray for tonight.”

He told me he’d served in Vietnam; he used to mop the floors at the courthouse; he had a room at Grace Boarding House three blocks east—$480 a month, shared kitchen, bad coffee. He told me about sleeping through three winters in alleys before he landed on a list that put a key in his hand.

“But you know what?” he said, dusting crumbs from his fingers. “Life got better. Not fast. Not easy. But it did. You just don’t quit.”

The sandwich tasted like cold turkey and dry bread. It tasted like mercy. When he stood to go, he draped the rolled blanket over my knees. “You got fire, girl,” he said. “Let it burn right.”

Two days later I found myself in a temporary room at a shelter. Bare mattress, metal bed frame, plastic chair, a door that locked. More than I’d had in years. The cafeteria coffee was weak. The biscuit crumbled like chalk. Other women sat nearby, quiet, eyes on tables. We didn’t ask names. Survival is a language that doesn’t need introductions.

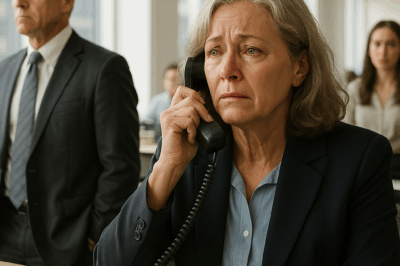

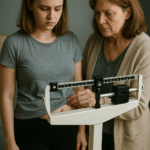

I learned quickly that abusers don’t just control rooms; they try to control records. When Shelley, a staffer with lemon cleaner in her office and a file with my name on it, called me in, I braced. “We received a report,” she said carefully. “Your stepfather claims you threatened him with a knife. That you’ve shown unstable behavior. They filed a secondary alert with Child Protection suggesting you may be a risk around minors.”

The room tilted. “They erased me on paper,” I said, not to her, not to anyone—just to the air. Then I asked for a copy.

There was my mother’s name—Monique Taylor, though she’d signed in the neat cursive she practiced for church bulletins: Mon’Nique Taylor. There was Greg’s blocky signature. In the blank labeled INCIDENT DESCRIPTION, someone had typed: Subject became agitated, threatening demeanor; attempted to harm family member. No mention of my fractured shoulder. No photo of my back. No porch. No deadbolt. Just a story tight as a fist.

In the library around the corner on K Street, you get one hour per person on the public computers. I used my sixty minutes like oxygen. The login code was scrawled on a scrap of paper by a woman with cat-eye glasses who called me “hon” without making it sound like pity. I opened a blank document and wrote:

This is how you erase a daughter.

The words came like floodwater. Cold toast. Missing toothbrush. The way they called me a mouth with legs. The education in silence. I found a quiet survivors’ forum buried beneath a dozen clicks and posted the piece. Not my last name. Not my picture. At the bottom I wrote:

My name is Kalin. I didn’t run away. I was thrown away.

I logged off and pressed my hands flat on the desk until they stopped shaking. The sun had the color of a bruise by the time I walked back to the shelter, but the air felt different. My story wasn’t loud, but it existed somewhere other than me now.

It wasn’t therapy that came first. It was clay.

Elijah drove me to a narrow storefront between a shuttered tax office and a laundromat whose neon OPEN sign flickered like a bad eye. A wooden board hung above the door: Cedar Clay. Inside the air smelled like wet earth and steeped tea. Bowls and cups lined shelves, each with the soft wobble that says somebody made me with their hands.

Behind the counter stood Evelyn: silver hair twisted up, apron stained with dried glaze, eyes like river stones—calm, not soft.

“You showed up,” she said.

“Elijah said… I might need help,” I said.

She slid a damp block of clay across the counter. “It’s okay to be clumsy,” she said. “It remembers everything. But it forgives easy.”

She didn’t ask about my arm. She watched how I held myself and set a stool near the wheel, showed me how to wedge the clay without using the muscle that screamed. “Symmetry is overrated,” she said when my first bowl collapsed. “Pottery is story. Even scars have shape.”

I stayed late. I pressed my fingers into the clay and let it give. The bowl I made wasn’t pretty. Its lip dipped where other lips rise. At the rim I carved two words with a wooden tool: still here. Evelyn fired it overnight and handed it back in the morning, soft gray, the letters faint under the glaze as if the bowl had whispered to itself while it cooled.

She also slid a small card across the counter: Assistant Clay Technician — Cedar Clay Studio. My name printed in block letters.

“You matter here,” she said. “Pay is small. Pride is larger.”

I became an apprentice to steadiness. We unloaded kilns in a heat that kissed the skin without burning. We sanded the edges of a cracked angel wing until it looked deliberate. On the quietest days the studio’s hum felt like a well-earned nap. When my hand shook, I learned to let the wheel steady me. Shape, breathe, lift. The clay taught me what a spine feels like when it isn’t bracing for impact.

A week later, a shadow darkened the doorway. The chime rang sharp. Braden—Greg’s son and perfectly-grown mirror—walked in with a smirk he must have practiced in the rearview mirror.

“Didn’t expect to find you playing house with mud,” he said, fingers trailing along a shelf like a vandal evaluating a wall. “Mom says you’re airing dirty laundry online. Poor little Kalin. Still performing.”

I set my bowl down carefully, turned, and looked at him until his smile faltered.

“You drove across town because you’re scared,” I said. “Because for once your version of me isn’t the only one in circulation.”

“You think this little craft project matters?” he scoffed.

“I think you don’t belong here,” I said. My voice sounded different to me—quiet, sure. I sat at the wheel, pressed a fresh block of clay to the center, and began. The wheel hummed. The clay lifted. My hands did what they had learned to do: shape something that didn’t exist into something that does. Braden watched, arms crossed, trying not to.

Evelyn stood close enough to catch me if I fell, far enough to let me stand.

When he finally left, the chime was soft again. Evelyn squeezed my shoulder. “That,” she said, “was strong.”

“I used to think silence was safety,” I said, breath slowing. “Now I know it can be power.”

I didn’t make revenge. I made proof. Bowls and wings and a small figure of a girl seated cross-legged with her arms folded like her own wings. I made a phoenix with feathers built from copper wire and discarded belt buckles I pulled from a cardboard box under Elijah’s bed—metal the color of harm, reshaped into something that rises.

It took months to make enough work to fill a room. It took one invitation to open the door.

Part 2

It wasn’t a fancy gallery—two rooms and stubborn radiators—but the light fell through the front windows like a benediction. On a cold Saturday in December, a line wrapped around the block. People stood stamping their feet, breath puffing in small clouds, holding printed invitations with Cedar Clay — Reforged in thick black letters. Inside, lamps threw warm circles on pedestals; the wall plaster had been patched and painted by two volunteers who insisted that patched and painted is the miracle most rooms need.

You don’t realize you’ve been holding your breath for years until you hear a room exhale. That’s what it felt like when the crowd fell quiet and I stepped forward.

“My name is Kalin Ruth Bennett,” I said into the microphone. My voice made the rented speaker crackle just once. “For years I believed my story wasn’t worth hearing. That if I stayed quiet long enough, shame would fade. Shame doesn’t fade. It ferments until you crack.”

I let the silence sit next to my words like a friend.

“This isn’t a revenge exhibit. It’s an obituary for the silence.”

In the center under glass stood the reforged wing—dark ash glaze, one edge jagged, the base still scored with hairline scars that the kiln had sealed. The plaque read: Reforged Wing — created by a survivor of domestic and maternal abuse. We had planned to keep me anonymous; the crowd had other ideas. They didn’t come to see a tragedy; they came to see what comes after.

People moved in quiet arcs, pausing at the bowl with still here on its rim, at the small figure of a girl whose smile was not broad but certain, at the phoenix built from brass and copper and wire that had once held a body down. Some touched their throats. Some whispered. Some closed their eyes like the pieces were prayers you make with your hands.

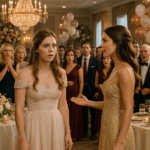

Near the back, pressed against the far wall like they couldn’t decide whether to stay or run, stood Mom and Braden. She wore the trench coat she believed made her look expensive; he wore a smirk that didn’t look like it fit as well as it used to.

“She’s always been theatrical,” Mom said to no one, just loud enough. “We raised her with structure. Boundaries.”

A woman with a press badge clipped to her blazer turned. “She sculpted your cruelty into something people paid to see,” she said evenly. “That’s not drama. That’s art born from survival.”

A man in a suit with the tired excitement of someone who funds hard things approached, card in hand. “Ms. Bennett? I’m with the National Foundation for Contemporary Arts. We’d like to discuss a curated tour. New York. Chicago. Possibly London.”

Mom stepped forward like a person cutting to the front of a communion line. “We’re her parents,” she announced, smile pinned on. “So proud of her resilience.”

I met the man’s eyes. “They’re not here to support me,” I said. “They’re here to claim me now that the clay’s worth something.”

He slid the card into my palm, looked at Mom as if she were a stain on an expensive fabric, and said, “We’ll be in touch—with you.”

A reporter lifted a microphone. “How much of this is autobiographical?” she asked.

“All of it,” I said. “I was beaten with a belt for not filling a plate fast enough. I was thrown out with a broken arm, one dollar, no toothbrush. When I spoke up, my own mother called me a liar. But I didn’t rot. I re-formed.”

Applause began as a tremor and swelled until the radiators rattled. Mom’s face emptied, that quick. Braden tugged her sleeve; for once she shook him off. They left without another word, and my shoulders didn’t lift to watch them go. Shadows shrink in good light; they did what shadows do.

After the closing reception, after Elijah swept cups into a black trash bag and Evelyn pulled the lights off one by one, I stood in the back room with a small candle and a lump of clay. I pinched the clay into a ball, held it over the flame, then pressed my thumb into its warm belly. On a shelf behind me sat a small rock from a creek behind a house I no longer lived in. I set the clay beside it and whispered, “For the girl who waited for someone to open the door.”

The next week we took the phoenix off the studio wall long enough to mount it on a brass bracket under brighter lights. The plaque under it read:

PHOENIX (rebar, belt buckles, copper wire, clay)

by Kalin Arden

for the girl who survived

People stopped in front of it. A teenager with a shorn head traced the edge in air. A woman in a navy coat pressed her palms together like she’d found an altar in a gallery. A man with a stethoscope in his pocket stood so long I wondered if he was stuck; then he exhaled, wiped his eyes with the heel of his hand, and left without speaking. I didn’t need to explain the piece. The piece explained me.

The letter came in a cream envelope with tight handwriting I knew like a scar.

Kalin,

I was raised hard. I raised you harder. Maybe too hard. I see that now. I don’t expect anything. Call if you want.

Mom

It wasn’t an apology. It was an arithmetic error. I placed it on my windowsill next to the creek rock and let the winter sun bleach the paper. Not every door needs answering. Especially not ones that lock behind you.

“Will you call her?” Evelyn asked when I finally told her.

“Maybe one day,” I said. “Not today.”

“That’s fair,” she said, and handed me a thermos of chamomile and a scone that tasted like a childhood I didn’t get to keep.

My apartment wasn’t much—one bedroom above a law office, a kitchen where the oven ran fifteen degrees hot—but it was mine. I mounted a shelf I’d sanded myself from a piece of salvaged barnwood. It creaked under weight but held. On it I placed three pieces like a family that made sense: the bowl with still here on its rim; the cracked angel wing, base mended with gold in the old Japanese way; and the phoenix that caught afternoon light like fire.

In the corner by the window sat the little figure of the cross-legged girl with her own arms folded like wings. She didn’t look brave. She looked calm. On the nights when sleep ran from me, I looked at her until my nerves followed her lead.

The library on K Street invited me to teach a writing hour. Ten chairs in the meeting room, a whiteboard that squeaked when you capped the marker. I wrote YOUR VERSION FIRST across the top and told them what I’d learned with my back against a light post and a gas-station water bottle in my hand: if you don’t write your own story, someone else will, and then you’ll spend your life begging to edit your own life. We read Mary Oliver and Audre Lorde aloud without asking for permission. A man with a gentle jaw wrote: I am allowed to be loud. A woman with nail polish bitten off wrote: I was thrown away, not run away. We clapped for each other until the security guard stuck his head in and said, “Five minutes.”

At the bookstore on 8th and Milner, the community reads night became a ritual. Elijah always saved me the same seat—second row, middle, near enough to feel eyes without feeling trapped. The host always said, “Borrow warmth. Return later.” I never returned it. No one asked me to. The first time I read there, my hands shook so hard I had to put my notebook on my lap to hide it. The last time, I didn’t bring a notebook. I brought the truth and a way to set it down gently.

People came and went. Some left notes tucked between studio shelves or slipped under the gallery door—me too, thank you, I told someone because of you. Some came back with their own hands full of clay. Some stayed to mop floors because loving a place sometimes looks like cleaning it.

On a Tuesday afternoon, while I was mixing glaze, a courier delivered an envelope with a logo from the National Foundation for Contemporary Arts. I opened it with fingers that remembered how to shake and didn’t. The curated tour was a yes. New York in spring. Chicago in fall. Maybe London, if the funding aligned.

I taped the letter inside the studio office cabinet where I kept spare batteries and tea bags. I didn’t want it on a wall. I wanted it where the work lived.

A month later, I stood in a different room with different light and watched strangers in a different city stand in front of the reforged wing and begin to breathe like they had been holding it too long. A woman touched her throat the same way the woman in Bakersfield had touched hers. A teenager took a photo of the word still on the bowl’s rim where the light caught it. A journalist asked why I’d chosen to put belt buckles in the phoenix; I told him, “Because all the materials of harm can be remade.” He wrote it down. I hoped he kept it.

One morning, between installs and interviews and flights that made my skin feel like paper, I got a voicemail from an unfamiliar number. My father’s voice sounded smaller than I remembered. “I know I can’t call,” he said. “I know this violates. I just… I’m sorry.” He hung up before the message could learn to be anything else.

I saved it in a folder called Not For Me and forwarded it to my lawyer with a three-word note: Please enforce order. Some things you do not let back in, no matter how they knock.

The last time I drove past the old house, it had a tricycle on the grass and a wind chime under the eaves. It didn’t look like a crime scene anymore. It looked like a house. My son—years older now—leaned his forehead against the window and said what he’d said that first night: “They can’t hurt us.”

“They can’t,” I said, and felt the sentence arrive all the way down.

Years from the night I left with one dollar and no toothbrush, I still sometimes wake to the sound of leather sliding through loops. I still sometimes reach for the deadbolt. But mostly, morning is coffee and a blue bowl that says still here and a dog who learned quickly that my lap is safer than the couch. Mostly, my life is small and exactly the right size: a studio full of dust motes and tea, a shelf full of pieces that tell the truth with curves and cracks, a kitchen where love is measured out in spoons and salt and forgiveness.

Mom thought she had made me a tool. Greg thought fear would keep me soft. Braden thought silence would last forever. They didn’t understand the basic chemistry of a life: enough pressure, enough heat, and you don’t shatter—you change form.

On the smallest wall of my apartment, I mounted one more shelf. It creaked under weight, then held. On it I placed a new piece: a small phoenix with wings outstretched, feathers made of the thinnest slices of brass, burnished till they caught the morning. I pressed my thumb into its breast while the clay was still damp and left the imprint there, a heartbeat’s memory.

They raised me like a tool and tried to throw me away. I learned to be a kiln. I learned to turn the worst materials into something that glows.

I didn’t just survive them. I made a life they can’t touch.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS. CH2

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS Part 1…

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call. CH2

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call….

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant. CH2

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

End of content

No more pages to load