Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever

Part One

The morning I discovered that the heirloom was gone felt like the ground had been pulled out from under me. It wasn’t just any item. It was the item, the one thing in my possession that connected me to my grandmother, the woman who had been my guiding light in so many ways. It was her necklace, an intricately designed piece of gold and emerald that she had worn in every family photo, for every milestone moment, every joyful occasion.

She had always told me, “This necklace isn’t just jewelry. It’s a story.” A story that now I realized had been stolen from me. It started when I went to retrieve the necklace from the box where I always kept it. I was planning to wear it to a small gathering with close friends, partly as a way to feel her presence with me, even years after her passing.

But as I opened the box, my heart stopped. It was empty. At first, I told myself it had to be somewhere else. Maybe I’d moved it. Maybe someone had borrowed it. But no matter where I looked, the necklace was nowhere to be found. Panic quickly set in as I tore through my drawers, the closet, every corner of the house where it might have been misplaced.

But deep down, I knew that necklace had one specific home. I never moved it. I never risked losing it. Someone else had taken it.

I held the empty velvet like you hold bad news—too tightly, as if force alone will reverse time. The cutout in the cushion matched the shape of the pendant perfectly, a green silhouette burned into red, a negative where something essential used to be. I pressed a thumb into the impression and felt the hollow echo in my chest.

Downstairs, the kettle sang to nobody. My coffee had gone lukewarm. The house wore the same Tuesday it always wore—sun through blinds, the dust of ordinary life—but all of it felt like a set, as if someone had quietly replaced the props overnight. The one important thing missing proved the whole scene was false.

I went downstairs to ask my mom if she had seen it, hoping against hope that she might offer a simple explanation. Maybe she had taken it to clean it. Maybe she’d put it somewhere for safekeeping. But when I asked, her response stopped me in my tracks.

“Oh, that old thing?” she said, not even looking up from her phone. “I sold it.”

The sound left my mouth before I knew I’d decided to let it go: a small, hard laugh, the kind that accidentally escapes when the world misbehaves too absurdly for language.

“You sold it?” I echoed. My voice wobbled on the second word. She finally glanced up, unfazed, like I had interrupted her during a commercial break.

“Yeah, it was just sitting there gathering dust. I figured you’d thank me later. I got a pretty good price for it.”

I stared at her, the way you stare at a cracked windshield, trying to determine if it’s spidering further.

“You sold Grandma’s necklace. The one she left for me.”

She shrugged, dismissing my outrage like it was nothing more than an overreaction.

“It’s just a necklace,” she said. “It’s not like you were even wearing it. And besides, now we’ve got some extra cash. You’ll get over it.”

There are moments that split a life into Before and After without asking permission. Sometimes they arrive like explosions. Sometimes they arrive in sweatpants with a phone in their hand and the news that your history has been converted into cash. The casualness of her response, the complete lack of remorse, made my blood boil.

This wasn’t just about the necklace. It was about what it represented. It was about the memories, the stories, the legacy that had been passed down to me. And she had treated it like it was nothing more than a trinket, something to be sold off for convenience.

I stormed out of the room, too angry to say anything more. On the stairwell landing, the old family portraits looked down: Grandma at twenty in a white dress; Grandma at fifty, a corsage pinned to a blue suit; Grandma holding me in a hospital chair, her necklace tucked against my newborn cheek like a blessing. All that gold, all that green. The chain had always looked delicate until you tried to break it—then you discovered what it had survived.

My hands were still shaking when I reached my bedroom. I closed the door and leaned my forehead against the wood until the cool of the paint quieted the heat under my skin. Somewhere beneath the anger was a second, smaller emotion I didn’t want to name. The one that sounded like a child crying behind a closet door: Why didn’t you protect me?

I knew I couldn’t let this go. I couldn’t let her get away with this. That necklace was mine, and I was going to get it back, no matter what it took.

You can learn a lot about a person from the way they justify theft. The phrase “You’ll thank me later” grew claws and climbed into my head. It wasn’t a prediction; it was a dismissal. A life’s worth of small erasures had been building toward this one. The time she gave away my childhood bicycle without asking. The time she “borrowed” the cash I’d saved for senior trip and forgot to return it. The time she told Aunt Susan I didn’t want Grandma’s patchwork quilt, when in fact she’d sold it at a yard sale because it looked “old.”

That afternoon I did something I should have learned to do years ago: I wrote everything down. I opened a blank document and titled it “The Story.” Under that, I started a list: Date. Event. What was said. How it made me feel. It wasn’t for court, not yet. It was for me, a record that said I saw what was happening and would no longer agree to forget.

Over the next few days, I started piecing together the clues. My mom, of course, refused to give me any details about where she had sold it. “It’s none of your business,” she snapped when I pressed her for answers. But I wasn’t about to let her stonewall me.

There are only so many places to turn heirlooms into money without getting questions. I went through the mail on the hall table, the way children of the habitually careless learn to do. I didn’t steal anything; I took photos. Two bank statements. A hardware store receipt. And there: a printed withdrawal receipt stapled to a deposit slip. The deposit was odd—an amount rounder than our bills ever were and dated two days prior. I swallowed the anger and the pride and asked in a voice I hoped sounded indifferent if she could text me the login to our joint account so I could pay the electric bill online.

“Don’t you have it?” she said, thumbs fluttering.

“I must’ve deleted it when I updated my phone,” I lied. She shrugged and read it from a sheet of paper stuck to the fridge with a magnet: a ridiculous password in the form of a dog’s name and a birthday.

Sure enough, I found a transaction from a pawn shop just a few days earlier. That was my first lead.

The pawn shop wasn’t far: a strip of glass and chrome wedged between a vape store and a deli that swore it made the best pastrami in three counties. The bell over the door jingled, that cheerful sound that always feels at odds with the business of desperation. Fluorescents hummed. Glass cases shone with other people’s mistakes: watches engraved with names not in the room, coins that had once lived in pocket jars, cameras with the strap still warm from someone’s neck.

I approached the counter, trying to steady my voice as I described the necklace. The shop owner—a man with calm eyes and the kind of hairline that had given up without losing dignity—gave me a long look before shaking his head.

“Sorry, miss,” he said. “It’s already been sold.”

It was the kind of sorry people say when they mean it and also mean they have no intention of helping you further because policy.

“Sold?” I repeated, my voice barely above a whisper. The pendant had been worn by travelers and brides and a woman who taught me to thread needles by the light of a kitchen window. Now it had passed through a glass case without my knowledge, pressed into someone else’s palm.

He nodded, offering a half-hearted apology. “It was a beautiful piece. Went fast. But if you want, I can give you the buyer’s contact info. They seemed like a collector. Maybe they’ll be willing to part with it.”

I blinked. “You can do that?”

“We keep a file on high-value sales for insurance. You can ask; I can say no. I don’t see the harm in sharing a public email. People sell; people change their minds. It’s Newbridge. Everyone’s connected to everyone.”

He pulled a three-ring binder out from under the counter and turned it so I could see. He ran a finger down a column of dates and found the line. A yellow sticky note bloomed. He wrote with a deliberate slowness that somehow felt respectful.

It wasn’t much, but it was a start. I took the contact information, my mind already racing with ideas for how to approach this mysterious buyer.

On the drive home I practiced the two stories: the one where I begged and the one where I negotiated, and then I decided to write neither. When you want something back that shouldn’t have been taken, there is a way to ask that is neither beggar nor thief. My grandmother would have called it “standing up straight.”

That night, I sat at the little desk in my bedroom and crafted an email to the person whose name belonged to a Gmail that sounded like it should be printed on a business card: Sylvia Hart – Antiquities & Appraisal. I chose my words carefully, sanded the splinters of anger off, left the grain of truth.

I explained the situation. I did not call my mother names. I said the necklace had been in my family for three generations and had significant sentimental value well beyond its appraisal. I attached a scanned photograph: Grandma at twenty-two, cheeks like summer apples, the emerald petals of the pendant resting just below the hollow of her throat. I said I would be grateful for the chance to talk.

To my relief, she responded quickly.

Her tone was polite but firm. She understood the necklace’s significance to me, but she had purchased it legally and wasn’t obligated to return it. However, she added, she might be willing to consider parting with it for the right price.

I put my forehead down on the desk for one very small moment. The thought of buying back something that was already mine felt both infuriating and humiliating, but I didn’t have a choice. If this was what it took to get the necklace back, so be it.

The next step was finding the money. Sylvia’s asking price wasn’t astronomical, but it was far more than I had on hand. I sold a few personal items, dipped into my savings, and even reached out to a couple of close friends who were willing to lend me small amounts. Every dollar I gathered felt like a tiny victory, a step closer to reclaiming what should never have been taken in the first place.

On the fourth day of fundraising I walked into the spare room where I kept boxes of “someday sells” and opened the lid of a carton labeled BOOKS—RARE. On top lay my first edition of The Secret Garden, a gift from Grandma on the day I turned ten. I cradled it, ran a finger over the foxed edge of the dust jacket, and put it gently back. There are some things you don’t sell, even for other things you cannot bear to lose. The calculus of love is complicated; sometimes it ends exactly at the borders of your own heart.

But there were other items—shoes I had never worn, a set of copper pots I’d convinced myself I needed during a pandemic bread-baking phase, a camera I used twice because my phone was easier. I listed them all. The texts from friends came in like postcards: Take your time paying me back. I loved Grandma’s lemon bars too. She would be proud of you for pushing. Each note turned a knot in my stomach into a ribbon I could breathe past.

A week later, I found myself standing outside Sylvia’s house, a charming old Victorian with a garden full of blooming roses. The kind of house that says someone loves old things in the correct way. I clutched the envelope of money tightly in my hands, my palms damp with nervous sweat.

When Sylvia answered the door, she was nothing like I had imagined. No velvet headband, no cloud of perfume. She wore jeans and a linen shirt and the uncomplicated, curious gaze of someone who believes objects and stories can fix one another.

She invited me in and offered me tea as though I were an old friend. “You’re the granddaughter,” she said, as if the word was a title. I nodded and she smiled. “I hoped you’d write. The necklace has the kind of weight a person carries with purpose.”

The living room smelled faintly of beeswax and old paper. Sunlight slid across the floorboards and glowed in the window glass like honey in a jar. She gestured toward a small mahogany box on the coffee table.

“The necklace,” she said softly, “is one of the most beautiful pieces I’ve come across. When I bought it, I wanted to believe it had been sold with consent. Now I know better. Your email felt like the ending the piece was asking for.”

When she brought it out, my breath caught in my throat. There it was, my grandmother’s necklace gleaming softly in the afternoon light. For a moment, I couldn’t speak, couldn’t move. Seeing it again felt like seeing a piece of my grandmother herself, like she was right there in the room with me.

Sylvia sat back on her heels the way people do when they mean to get out of the way of a reunion. “May I?” she said, and I nodded. She fastened the clasp at my neck with the deftness of someone who had done this a thousand times for people crying in rooms like this. The emerald cooled my skin. The chain remembered me.

I handed over the envelope and Sylvia placed the necklace in my hands. “Take good care of it,” she said with a kind smile. “It’s clear it belongs with you.”

On the way home, the pendant tapped against my sternum like a small heartbeat, steadying the one inside me.

But the story wasn’t over yet.

I still had to face my mom. She needed to know what she had done, not just to me, but to our family’s legacy—and she needed to understand that this would be the last time I let her take something from me without consequences.

When I got home, I found her in the living room scrolling on her phone as if nothing had happened. I walked in holding the necklace out in front of me.

“Recognize this?” I asked, my voice calm but firm.

She looked up, her eyes widening in surprise. “How did you—” she began, but I didn’t let her finish.

“I got it back,” I said. “Because unlike you, I understand what this necklace means. It’s not just jewelry. It’s not just something you can sell off because you felt like it. This is our history. This is Grandma’s story. And you had no right to take it.”

For the first time, she looked genuinely uncomfortable. “I didn’t think it was that big of a deal,” she said, defensive. “I mean, you weren’t even wearing it.”

“That’s not the point,” I interrupted, my voice rising. “The point is that you decided—without asking me—that something priceless to me was worthless to you. And then you laughed it off like it didn’t matter. But it does matter. To me. To our family. To the memory of the person who gave it to us.”

She didn’t have much to say after that, whether it was guilt, embarrassment, or just a desire to avoid further confrontation. She remained quiet as I turned and walked out of the room.

I went upstairs, closed my bedroom door, and took the necklace off long enough to put it back in the velvet cushion it had occupied for years. It clicked into place. The outline filled. The world aligned by a small degree.

On my desk, “The Story” file waited. I added a line: Returned to rightful owner on Tuesday. Paid in paper. Paid in resolve.

I didn’t sleep much that night. Instead I sat on the floor with my back against the bed and made a list not of events but of decisions. It ended with one sentence that felt like it had been waiting for me to write it for a very long time: This ends here.

What happened next would not only test my determination, but change the way I saw my mom and myself forever.

Part Two

“She’ll regret it forever” is the kind of sentence that sounds dramatic until you realize regret is simply a calendar with the same event circled every day. Regret is not a scream; it’s a metronome. You don’t have to punish someone for that to happen. You just have to stop protecting them from their own choices.

The first thing I did was talk to a lawyer.

Her name was Marta, and she wore suits the color of good arguments. In a conference room that smelled like toner and coffee, she listened without interrupting while I told her everything—from the empty velvet box to the pawn-shop binder to Sylvia’s living room and the weight of the clasp at the back of my neck.

“Legally,” she said, “your mother committed conversion—the civil kind, not the spiritual kind. She interfered with your property rights and deprived you of the use of your necklace. Criminal charges would be theft, maybe, but prosecutors don’t love domestic disputes over property. Civil court loves receipts.”

She slid a notepad across the table. “Do you want to sue her for the appraised value and costs? Or do you want something else?”

I didn’t want money. I wanted a boundary with teeth. I wanted a letter from a neutral party on paper with a header that said the future is different now.

“Draft a demand letter,” I said. “Ask for reimbursement of everything I spent to get it back: the price, the gas, the appraisals. Include the pawn shop transaction detail and the fact that she refused to disclose where she sold it. And include this.”

I pushed “The Story” printouts forward. Marta scanned them, eyebrows lifting at the “You’ll thank me later” headline scrawled at the top.

“Not admissible as anything but narrative,” she said, “but persuasive as hell.”

“And I want a stipulation,” I added, the words clarifying as I spoke them. “No member of the family touches or sells or loans or consigns any inherited item without the written permission of the named heir. If they do, the heir is entitled to three times the appraised value and fees.”

Marta smiled. “Punitive liquidated damages. Love a woman who reads her contract templates. We can attach the stipulation to a family property memorandum and a trust if you want to go big.”

“Big,” I said. “But not vindictive.”

“There is a difference,” she said, and wrote quickly. Her pen made a sound like sewing: thread through cloth, steady, strong.

The second thing I did was take the necklace—not to a safety deposit box, not to a museum—but to a jeweler Grandma loved, a woman named Leena who kept a loupe in her pocket and addressed all objects as she, as if every piece had a name and a history and a personality you should respect.

Leena held the pendant like an old friend. “She’s tired,” she said softly. “She’s been through hands.”

“Can you make her strong again?” I asked.

“I can make her as strong as the day she left your grandmother’s neck,” Leena said. “Maybe stronger. But promise me something.”

“What?”

“Promise you will wear her,” she said. “Not lock her away. Stories don’t live in boxes.”

I promised. When I left, the chain sat against my collarbone like an oath.

The third thing I did was go through the house. Not to inventory valuables or search for hidden cash. To decide what, if anything, I wanted to fight for next. In a back closet I found a shoebox of letters tied with ribbon—the good kind of old, not the sellable kind. I put them on my own shelf. The tin of recipes written in Grandma’s looping hand went into my kitchen. The rest—the clutter that had turned our history into hiding places for shame—I put in the donation bin. People imagine revenge as fire. Mine looked like daylight.

Marta’s letter went out on Friday.

It was not cruel. It was clear. It detailed the facts in numbered paragraphs and ended with a sentence that contained no threat—only consequence.

Kindly remit payment in the amount of $3,642.18 within thirty (30) days of the date of this letter. Should you choose not to comply, we will file suit for conversion and seek damages, costs, interest, and equitable relief, including injunctive relief prohibiting you from disposing of family property without written consent of the heir. We sincerely hope such an action will be unnecessary.

On Monday, my mother stopped speaking to me.

Silence can be a weapon, but it can also be a surrender. She left coffee cups in the sink and walked around me without making contact with either shoulder. No apologies. No explanations. At dinner, the clink of fork against plate sounded like rain in a tin roof.

On Wednesday, I came home to find a note on the kitchen counter in her handwriting: Fine. Take your precious things. I’m not going to jail because you’re dramatic. Money will be paid.

The next day, a cashier’s check arrived at Marta’s office for the full amount. No memo line. No apology there either. But the money’s indifference pleased me. It was just arithmetic. I deposited it and paid everyone back. I kept Leena’s receipt and my gas station slips in a folder labeled SETTLED.

And then, finally, I did the thing that made her understand regret, not as an emotion but as a structure she would have to live inside for a long time.

I built the Hannah Rowan Trust.

Hannah had been my grandmother’s name. She had never been rich, but she had been generous like water. The trust was not big either—three lines on a form, a bank account that hummed from the small engine of my freelance checks and the money I no longer spent on things that pretended to be comfort. The trust existed for two purposes only:

- To fund the preservation and ethical transfer of family heirlooms—appraisals, insurance, restoration—and

- To sponsor one young woman a year in a short course called

Standing Up Straight

- , which involved financial literacy, boundary-setting, and the legal basics of protecting yourself from your own people when necessary.

The first seminar took place in the basement of the library because that’s where things that change lives often start. I wore the necklace. I did not mention my mother by name. I talked about the difference between forgiveness and permission, the difference between value and price, the difference between inheritance and ownership.

Two months later, the local paper ran a small piece in the community section with a photo of me standing beside a black-and-white poster of Grandma smiling out of 1961. The caption read: Granddaughter Honors Local Teacher With Trust For Women’s Heirlooms. Somewhere between the classified ads and a story about the high school’s robotics team, my mother would find the words “honors” and “trust” and know both were aimed over her shoulder.

We lived like roommates then. A thin plastic of civility stretched over everything, the kind you pull taut across a bowl and hope doesn’t tear when you put it in the fridge. I stopped narrating my schedule; she stopped offering opinions. On the first Sunday of October, she knocked on my door and asked, “Are you wearing it to the Harvest Dinner?”

“The necklace?” I said. “Yes.”

“Fine,” she said, and the syllable sounded like surrender. Then, almost too quietly to hear: “She would like that.”

At the Harvest Dinner, I felt the weight of eyes on the emerald. Neighbors asked gentle questions. Aunt Susan reached out and touched the pendant like a small reliquary. “Your mother told me you got it back,” she said. “I’m glad. Your grandmother would haunt us all if we let it go to strangers.”

“She would set off smoke alarms until we confessed,” I said, and Aunt Susan laughed, and some segment of the night’s awkwardness softened.

I would love to tell you that after that, my mother and I learned each other’s languages overnight, that the apology arrived on linen paper and the house refilled with the kind of love that makes the evening news. The truth was less cinematic and more useful.

In November, she asked me where I had the necklace restored. “Leena on Maple,” I said. “Tell her you’re my mother. She’ll give you the chair by the sunny window.” Mom nodded. A week later, a ring that had belonged to my great-grandmother appeared on the kitchen table in an envelope from Leena’s shop with a receipt for cleaning and a fresh appraisal. “For Thanksgiving,” Mom said. “Since you’re hosting. Maybe put it in the trust file.”

On Christmas morning, we ate pancakes at the dining table and she handed me a box wrapped in plain brown paper. Inside was a spiral-bound book with a photo of Grandma on the cover and a title printed in mocked-up typewriter font: Hannah’s Necklace: A Story In Receipts. I opened it to find scans of everything—photo albums, appraisals, a copy of my text to her from the day I found the box empty. She had been paying attention after all.

“Regret,” she said, not looking at me, “is different up close.” She took a breath. “I’m sorry.” The words didn’t heal old wounds; they stopped new ones from forming. Sometimes that’s the best a human can do.

And then, because the universe enjoys symmetry, the pawn shop called.

“You should know,” the owner said, “a man came in yesterday with two pieces that look like they belong with your grandmother’s necklace. Not from your mother. From a house clear-out. I’d feel better if you had the chance to see them.”

I drove straight over. In the glass case lay two emerald drops—earrings that once hung like leaves from Grandma’s ears in a photo from before I was born. I recognized them the way you recognize a melody you didn’t realize you remembered until the second verse. They were priced in a way that said someone understood what they were worth to someone somewhere.

“How much for family discount?” I asked. The owner smiled and quoted me a number that made sense for all parties. I paid. I took them to Leena, who laughed with delight and called them “the chorus.” “You know what this means,” she said. “The set is singing again.”

That night, I brought the earrings home and set them on the kitchen table in front of my mother without comment. She reached out with the same careful hands she used to lay baby blankets over my nephew’s sleeping body.

“She wore these when she danced,” she said. The first memory she’d offered without prompting. “She said they swung time into place.”

“Do you want to try them on?” I asked. She nodded, and I fastened one, then the other. She caught her reflection in the microwave door and went very still. “I remember this feeling,” she said. “Like being in a photo and a heartbeat at the same time.”

This was not my revenge. This was my repair. Those are not the same processes, but sometimes one uses the other’s tools.

An invitation arrived in the mail a week later: a small local museum was putting together an exhibit called Told In Gold: Stories of Family Jewelry. The curator asked if the Hannah Rowan Trust would consider loaning the necklace and earrings for a month, with proper security and a plaque describing their history.

I called Marta. “If I loan them, will it avoid any future claim of abandonment or public domain?”

“They’re yours,” she said. “Just get everything in writing and take a photo of the display card. Your grandmother would find this funny.”

I loaned them. The plaque read:

Hannah’s Necklace (c. 1958) & Earrings (c. 1960)

Gold, emerald, memory

Worn by teacher and community organizer Hannah Rowan at graduations, weddings, and first days. Taken once without permission, reclaimed by a granddaughter who believed objects have stories and stories have owners. On loan from the Hannah Rowan Trust for Heirlooms & Learning.

On opening night, my mother stood in front of the glass case and read the plaque silently twice. Her eyes were wet at the edges. When she turned to me, there was something like a smile that knew it had been earned.

“Will you ever forgive me?” she asked.

“I already did,” I said. “The day you wrote the check and left the note. Forgiveness is not forgetting. It’s deciding not to carry your mistakes for you anymore.”

She nodded. “That sounds like your grandmother.”

“It sounds like me,” I said. “Which is why she would have liked it.”

After the exhibit closed, I took the pieces home. I still wore the necklace often—on ordinary days and on extraordinary ones. When I taught the second session of Standing Up Straight at the library, a girl with a buzzcut and a black hoodie hugged me awkwardly and said, “My mom sold my dad’s Navy ring to pay a bill. I thought I had to just eat it.”

“You can be compassionate about circumstances and still insist on justice,” I told her. “It isn’t either/or. It’s and.”

She nodded like a person storing a map.

As for my mother, regret did its work—not as a punishment, but as a practice. In February, she brought me a stack of photo albums and asked if we could scan them into the Trust drive together. In March, she called Aunt Susan and apologized for the quilt situation from ten years ago and returned the cash Aunt Susan secretly sent to my Venmo for the necklace fund. In April, I came home to find a Post-it on a box: Your watch from Grandma. I had it cleaned. Don’t thank me later. Do it now. Love, Mom.

I laughed. I thanked her then. The sound felt like spring.

And because every good story about taking back what was yours should end with an unmistakable gesture, I did one more thing—the smallest, sharpest thing I could think of.

For Mother’s Day, I gave her a present wrapped in plain brown paper: a framed print of the museum plaque. In the matting, just below the title, I had the framer letter two lines in tiny type:

“It’s just jewelry.” — said once, wrongly.

“It’s a story.” — said forever, rightly.

She hung it in the hallway without comment. Now, every time she walks past it on the way to the kitchen, to the laundry, to her phone buzzing on the table, she passes her own sentence and the correction that made it human.

The necklace sits safely in its box when it isn’t resting against my skin. I wear it more often than I used to. Every time I put it on, I feel a sense of pride, not just in the piece itself, but in the journey it took to get it back. It’s a reminder that some things are worth fighting for, that standing up for what matters can lead to strength you didn’t know you had.

As for my mom, things between us are still complicated. Trust isn’t something that can be rebuilt overnight, and I’m not sure it ever will be entirely. But one thing is certain: she knows now that I won’t let her dismiss or undermine what’s important to me. She knows because there is a trust with her mother’s name on it and a plaque she cannot avoid and a daughter who has learned to turn “You’ll thank me later” into a sentence with a different ending.

That’s my revenge: not her shame, but her education. Not my anger, but my boundary. Not her silence, but her yes to a new rule we made together in the wreckage of the old one.

And in the end, that’s a lesson worth learning—one she’ll remember every time the emerald catches light and throws it back like a promise kept.

Part Three

Regret is sneaky.

It doesn’t arrive with a thunderclap and a villain’s monologue. It shows up in quieter ways: a hand hovering over a jewelry box that isn’t there anymore, a pause in the middle of a sentence that never makes it to the end. It was in the way my mother started looking at objects.

Not with that old casual appraisal—Can I get rid of this?—but with a weight behind her gaze, as if every chipped bowl and photo frame carried a question: Who would miss this if it vanished?

In the months after the trust, after the lawsuit-that-wasn’t, after the museum plaque, my mother became careful.

Too careful, almost. She wouldn’t throw away a cracked mug without asking if it belonged to somebody’s memory. She’d hold up a faded T-shirt from a charity 5K and ask, “Does this matter to you?” like she was holding a heart valve instead of cotton.

Sometimes I almost wished she’d snap, roll her eyes, mutter something about me being dramatic. That, at least, was familiar. This new hyper-vigilance made the house feel like an antique store in an earthquake zone: everything fragile, everything balanced, nothing entirely safe.

“Guilt’s too heavy a coat to wear all year,” I told Marta over coffee one afternoon.

“She’ll either take it off,” Marta said, “or learn how to carry it without making you hold the hem. Not your job anymore.”

“That’s the thing,” I said. “When she sold the necklace, I finally learned how to say no. Now I have to learn how not to say yes to taking care of her remorse.”

Marta stirred her coffee. “Welcome to Stage Two of Boundary Maintenance,” she said. “Stage One is ‘No.’ Stage Two is ‘Still no, but thank you for asking with better manners.’”

That second stage snuck up on me in an email.

Subject: Hannah Rowan Trust – Speaking Request, it read.

The sender was a woman named Elise, director of a small women’s shelter three towns over. She’d heard about the trust from a librarian who’d attended my first Standing Up Straight session.

We host life-skills nights on Wednesdays, Elise wrote. Your program sounds like exactly what our residents need—many of them have had family steal from them, sign leases in their names, you name it. Would you consider coming to talk? We can offer a small stipend and all the store-brand cookies you can eat.

I said yes. Not for the cookies. For the women whose stories the word “stole” barely covered.

The shelter meeting room was smaller than the library’s basement, with mismatched chairs and a whiteboard that had seen better eras. The women in the room ranged from nineteen to sixty, faces and hands marked with the kind of lines that don’t come from age alone.

I wore the necklace. It felt important that they see it with their own eyes, sitting where it belonged.

“I’m not a lawyer,” I said at the start. “I’m a person whose mother sold her grandmother’s heirloom necklace without asking and told her, ‘You’ll thank me later.’ Spoiler alert: I did not thank her later.”

They laughed—the brittle kind of laugh that comes from recognizing the shape of a bad story, even if the details differ. I told them the whole thing: pawn shop, Sylvia, Marta, trust, plaque. I watched their faces change at different moments. Some flinched at “joint bank account.” Others at “it’s just a necklace.” A few nodded with a weariness that said, I too have sat in a kitchen with someone who translated betrayal into practicality.

During the Q&A, a woman with cropped gray hair and a faded anchor tattoo on her wrist raised her hand.

“What if the person who took your stuff says you’re ruining their life by asking for it back?” she asked. “My sister sold my daddy’s medal. Said she needed the money for the light bill. Now she says me making a fuss is ‘tearing the family apart.’”

I thought about my mother, about the note that said Fine. Take your precious things. I’m not going to jail because you’re dramatic.

“People who benefit from your silence will always call your voice ‘drama,’” I said. “It doesn’t mean you’re wrong. It means you’re changing the script. And sometimes, yeah—sometimes standing up does tear things apart. It also keeps you from being torn apart slowly over years.”

After the session, Elise pulled me aside.

“Would you ever consider doing a version of this with… family?” she asked. “We’ve had a few moms come through here who realize, too late, that they were part of the problem. That they taught their kids the wrong things about love and ownership. Some of them are trying to fix it.”

I thought of my mother reaching for the earrings’ reflection in the microwave door.

“Maybe,” I said.

Two weeks later, I came downstairs to find my mother at the kitchen table with a legal pad, a pen, and her reading glasses perched at the end of her nose.

“I have a proposal,” she said.

It was a weird echo of the way she used to announce changes as if they were weather—inevitable, impersonal.

“What kind of proposal?” I asked, wary.

“This trust of yours,” she said. “The standing-up class. The museum. The… all of it. I’d like to help.”

“Help how?” I asked slowly.

“Admin,” she said. “Filing. Making calls. Sitting at the registration table. Telling my own story as a cautionary tale if you think it would… help.”

She looked at me over her glasses and, for a moment, I saw not my mother but a woman in her sixties who had discovered, late, that she was capable of hurting people she loved and was trying to find something to do with her hands that wasn’t clutching guilt.

“I don’t want to be the villain forever,” she said softly. “I know I was, for a while. I earned it. But I’d like to… do the opposite now. Teach women not to do what I did. To listen when their kids say something matters.”

The petty part of me wanted to say no.

To say, You don’t get to use my work as your absolution.

The part that had sat in that shelter and watched women flinch wanted to say yes.

Boundaries again. Always back to boundaries.

“We can try it,” I said. “But it’ll be my terms. You’ll be a volunteer, not the boss. And if at any point it becomes about making you feel better instead of them safer, we stop. Deal?”

She nodded.

“Deal,” she said.

Her first “shift” was at a Saturday afternoon workshop we hosted at the library: Protecting Your Stuff From People You Love. Marketing had argued for a softer title. I’d insisted on honesty.

Mom sat at the sign-in table with a stack of name tags and a plate of store-bought cookies—the respectable kind, not the neon-frosted ones. Women drifted in, some alone, some with friends, some with kids in tow.

“How did it go?” I asked after everyone had left.

She sat back, the legal pad now filled with notes—names, questions she’d overheard, ideas for future sessions.

“I heard a woman tell her friend, ‘My son thinks he can pawn anything in the house and I’ll just… let him,’” she said. “Another said her fiancé keeps ‘borrowing’ pieces of her jewelry for his sisters.”

She shook her head.

“If someone had told me thirty years ago that taking something your child treasures without asking is violence, not ‘tough love’…” She trailed off. “I might have done things differently.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Maybe not. But you know it now. That has to matter somewhere.”

She glanced at the necklace.

“It matters here,” she said, tapping her chest. “Every time I see that green flash, I remember the look on your face in the kitchen. That’s my forever.”

There it was.

Not my revenge.

Her regret.

Permanent, not by my punishment, but by the imprint of her own choices on her memory.

I didn’t need to twist the knife. The knife lived in the kitchen drawer now, labeled and obvious.

When the museum asked to borrow the pieces a second time—for a traveling exhibit, this time, touring regional cultural centers—Mom insisted on coming with me to sign the papers.

“This is the only way I’m letting them leave town again,” she told the curator. “Accompanied by my daughter and a stack of legal documents the size of a Bible.”

The curator smiled.

“You’d be surprised how often this comes up,” she said. “Families and jewelry. Families and anything, really. People think love entitles them to everything inside someone else’s life.”

“Not anymore,” my mother said.

The curator raised an eyebrow. “You’d be a good guest speaker for us,” she said.

Mom flushed.

“I’d rather just stand in the back and keep an eye on the glass,” she said.

“You can do both,” I said.

On opening night in the next town over, I watched kids press their noses to the display case, adults lean in to read the little placards. One teenage girl snapped a selfie with the necklace in the background, then frowned at the text.

“‘Taken once without permission, reclaimed by a granddaughter…’” she read aloud. “Dang. That’s cold.”

“Or warm,” her friend said. “Depends on who you are.”

My mother and I caught each other’s eye.

“Guests,” a docent called out. “In fifteen minutes we’ll have a short talk by the founder of the Hannah Rowan Trust and—”

“—her accomplice,” I added quietly. “Do you want to say a few words?”

She shook her head.

“I’ll stand next to you,” she said. “If anyone asks, I’ll tell them the truth.”

That turned out to be enough.

A woman about my mother’s age stayed behind after my talk.

“I’m here with my daughter,” she said. “I sold her grandfather’s watch when she was sixteen. She still brings it up. I tell her she’s being dramatic. I… don’t want to be that mother anymore.”

My mom stepped forward.

“I sold my daughter’s grandmother’s necklace,” she said. “Told her she’d thank me later. She did not. It almost cost me my relationship with her. Don’t do it. Go home. Tell your daughter you were wrong. Ask her how to make it right now, before she needs a lawyer to teach you where her boundaries are.”

The woman blinked, tears filling her eyes.

“How did you live with yourself after?” she whispered.

“I didn’t,” my mother said. “That was the point. I had to become someone else.”

Later, in the car, she turned to me.

“Did you see that girl behind her?” she asked. “The way she looked at her mom, like she wanted to believe her?”

“I saw,” I said.

“Do you ever think,” she asked, “that you wanted to believe me too?”

“Yes,” I said. “For a long time, I did. Then I wanted me more.”

She nodded. The streetlights slid over her face, alternating shadow and gold.

“I understand that now,” she said. “I wish I had sooner.”

There it was again.

Regret. Not as a wall between us, but as a bridge we had to cross carefully, boards creaking under our feet.

One night, maybe a year later, I came home to find my mother at the kitchen table with Grandma’s old recipe tin open between us.

“We have a request,” she said. “From your cousin. She wants Grandma’s lemon bar recipe. Says every time she tries one somewhere else, it tastes… wrong.”

“Give it to her,” I said.

She hesitated.

“You don’t want it protected in the trust?” she asked, half-joking.

I smiled.

“Not all heirlooms belong in folders,” I said. “Some belong in ovens and messy countertops. As long as she doesn’t open a chain called ‘Grandma’s Lemon Bars’ without credit, we’re fine.”

Mom laughed. It sounded less rusty now.

“I like this version of us,” she said.

“So do I,” I admitted.

“Your grandmother would too,” she said. “She’d hit me with a wooden spoon first, but after that…”

“She’d make us tea,” I said. “And tell us to stop wasting time when there’s dough to roll.”

We both looked at the necklace.

It glinted, quiet and steady.

Not revenge, not victory.

Just continuity.

Part Four

The last laugh, it turns out, doesn’t arrive with a punchline.

It arrives in glimpses.

In the way a once-casual thief of heirlooms flinches every time someone jokes about “borrowing this forever.” In the way she volunteers to be the one who double-checks the locks at museum exhibits. In the way she holds her grandson’s hand a little tighter when they walk past a pawn shop.

It arrives in paperwork, too.

When my mother decided to update her will, she asked if I would come to the appointment.

“You don’t have to,” she said. “But I’d like you there. To make sure I don’t… accidentally screw something up for you.”

“Accidentally,” I echoed. She winced.

“Fine,” she said. “Before I screw something up less accidentally than I admit.”

The attorney, a calm woman with a knack for cutting through small talk, asked us both questions. About assets, about debts, about intentions.

“Do you have any specific bequests?” she asked my mother. “Items you want to go to particular people?”

“Yes,” Mom said. “The house to be sold and proceeds split equally between my children. The contents of my personal jewelry box to be handled in accordance with the existing trust. Kitchenware and recipes to go to whomever is willing to host holidays. And…”

She glanced at me.

“…and I want a line in there that says I am barred from selling, pawning, or otherwise disposing of any property designated as an heirloom by my children, now and in the future. Retroactively, if possible. I know you can’t legally do that last bit, but I’d like it written down anyway. For the record. For the… joke.”

The attorney smiled.

“Not a joke,” she said. “A memorialization of growth. We can include a clause requiring the consent of any named heir for disposition of heirloom items. It’ll give your kids legal backing if anyone tries to do what you once did.”

“Good,” Mom said. “I want my mistake to be their armor.”

Later, when we left, she squeezed my hand.

“I know it’s weird,” she said. “Thinking about… all this. But it feels better, knowing it’s written down. Like I’ve installed my own deadbolt.”

“Welcome to the club,” I said.

Years passed.

We got older. The necklace stayed the same age.

I wore it to big things: the launch of our second community program, a gala where we raised enough money to expand Standing Up Straight to three more towns, a courthouse ceremony where a judge granted guardianship to one of our program’s alumni who’d aged out of foster care and wanted his baby sister to stay with him instead of strangers.

I wore it to smaller things too: grocery runs, parent-teacher conferences for kids whose parents couldn’t make it, Tuesday afternoon walks with my mother around the neighborhood.

Once, on one of those walks, we passed a yard sale. Folding tables lined the driveway, sagging under the weight of other people’s once-important stuff.

A woman about my age stood behind one of the tables, arms crossed, fatigue evident in the slump of her shoulders. She glanced at us, then at a box labeled JEWELRY $5.

My mother paused.

On top of the pile lay a small silver locket, dented but pretty.

“Excuse me,” Mom said. “Do you know what you’re selling there?”

The woman shrugged.

“Stuff from my mom’s house,” she said. “She moved into assisted living. Told me to get rid of ‘all that junk.’”

My mother picked up the locket gently.

“May I ask,” she said softly, “if you know anything about this?”

The woman frowned.

“Think my grandma used to wear that,” she said. “But she died when I was nine. Mom never wanted to talk about her. Said they didn’t get along. I don’t even have a photo of her.”

Mom turned the locket over, rubbed a thumb over the hinge.

“It’s your choice, of course,” she said. “But before you sell it… maybe open it. See if there’s a photo inside. Or a name. Just so you know what you’re letting go of.”

The woman hesitated, then took the locket and popped it open.

Inside, tucked under scratched glass, was a tiny black-and-white photo of a woman with eyes like hers.

“Oh,” she whispered.

My mother smiled.

“Sometimes the junk isn’t junk,” she said. “Sometimes it’s a story you didn’t know you had. You get to decide what it’s worth to you.”

We walked away, leaving the woman staring at the locket like it had just spoken.

“That was very… you,” I told Mom.

“I learned from the best,” she said.

“Grandma?” I asked.

“You,” she said.

I swallowed against the lump in my throat.

On the tenth anniversary of reclaiming the necklace, we held a small gathering at the library. Nothing grand—no media, no velvet ropes. Just folding chairs and cake and a poster board where people could write, in thick markers, a story about an object they loved.

One woman wrote about her father’s battered wallet, with his high school football photo still tucked behind the plastic. A teenager drew her grandma’s crockpot. A boy printed carefully: MY MOM’S WEDDING SHOES. SHE LET ME TRY THEM ON.

My mother wrote nothing. She stood, watching, her hands folded in front of her.

After everyone left, she approached the board.

“You’re not going to write anything?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“I don’t need to,” she said. “You know mine.”

“What is it?” I asked, curious what she’d say.

She reached out, touched the space where my grandmother’s name was printed on a small card at the edge of the board.

“My daughter’s spine,” she said. “Straight as a ruler now. Strong as steel. That’s my object.”

I laughed.

“You want to put that in the trust?” I asked. “Might be hard to appraise.”

She shrugged.

“Not everything needs a price,” she said. “Some things already cost enough.”

There it was—the last laugh.

Not mine alone, but ours.

Not a cackle over someone else’s downfall, but a shared, quiet amusement at the way life had looped back around: the woman who once sold her daughter’s heirloom now standing in a library basement, protecting strangers’ locket stories and complimenting her kid’s vertebrae.

When I think back to the day I opened that velvet box and found it empty, I still feel the drop in my stomach. The same way you feel that first unexpected jolt on a flight, even when you’re used to turbulence. But the fear that used to live in that memory has been replaced with something else.

A map.

From that moment—to the pawn shop, to Sylvia’s living room, to Marta’s office, to Leena’s workbench, to the museum, to the shelter, to the kitchen table, to the yard sale, to the library.

Every step a choice.

Every choice a small, stubborn refusal to let “You’ll thank me later” be the last word.

My grandmother was right.

The necklace isn’t just jewelry.

It’s a story.

Once, my mother tried to rewrite that story without my consent. She cut out chapters and sold them to a stranger.

I made sure she’d regret it—not by hurting her, but by insisting that the story be told whole. By building a trust with her mother’s name. By turning that moment of theft into a curriculum on consent and value and love that doesn’t require sacrifice.

She will remember what she did every time the emerald flashes in a mirror, every time she signs her will, every time she tells another woman, “Ask your kid before you sell that.”

That is her forever.

Mine is different.

Mine is the weight of the chain at my throat when I open the door to a girl holding a dusty shoebox, eyes wide, asking how to keep her stories safe.

Mine is the satisfaction of watching my mother pass her a tissue and say, without prompting, “Sit down. Let us tell you what we learned the hard way.”

Mine is knowing that the last laugh wasn’t really a laugh at all.

It was a decision.

To stop being the person stories happen to, and start being the one who writes them.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

They Tossed Her Bag in Front of Everyone — Then the Medal of Honor Hit the Floor

They Tossed Her Bag in Front of Everyone — Then the Medal of Honor Hit the Floor Part 1…

She Refused to Salute the General — Then Whispered a Name That Left Him Frozen

She Refused to Salute the General — Then Whispered a Name That Left Him Frozen Part 1: The Refusal…

A Simple Woman Handed Over Her ID — They Laughed, Then Collapsed When It Spoke Her Rank

A Simple Woman Handed Over Her ID — They Laughed, Then Collapsed When It Spoke Her Rank Part 1…

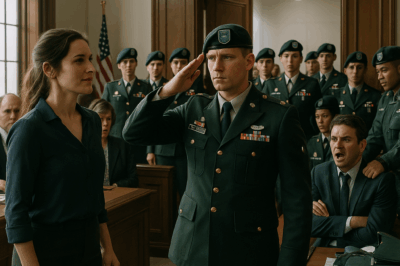

They Called Me Insane in Court—Then 12 Berets Burst In, Saluted Me ‘Major’ and Arrested My Brother

They Called Me Insane in Court—Then 12 Berets Burst In, Saluted Me “Major,” and Arrested My Brother Part One –…

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sister’s Wedding So I Took Revenge

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sister’s Wedding So I Took…

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off …

End of content

No more pages to load