Mom shouted, “Leave and don’t return!” So I did. Weeks later, Dad asked why I’d stopped paying

Part I: Keys on the Counter

I can still hear the exact sound the keys made when I set them on the counter—light metal on laminate, the tiny ring tapping once against the ceramic sugar jar like a gavel striking wood. If you’ve ever lived your life according to other people’s panic, you know how to quiet every movement, how to shrink in a room, how to become air. That night, I did the opposite. I put the keys down like punctuation. The end.

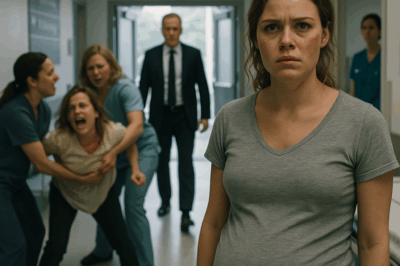

“Get out and never come back,” my mother said, and it wasn’t the sentence that broke me. It was the way she stood behind it—arms crossed, chin lifted, certainty blooming on her face like she’d been rehearsing in a mirror.

My father didn’t look at me. He was at the table with a stack of unopened envelopes spread out like cards he didn’t know how to play. The copper desk lamp illuminated the fine, papery edges of final notices, red stamps, a bank logo with too much confidence in its font. His shoulders were rounded in a way that made him look smaller, like someone had scooped part of him out and forgotten to fill it back in.

I didn’t argue. There had been a time when I would’ve tried to translate myself into their language—explanations, compromises, humor like a bandage—but I’ve learned there are moments that only accept silence. I slid my jacket on, picked up my phone, and left.

January air hit me in the face like a slap that believed in me. The neighborhood was the kind of quiet that holds thin secrets: a light left on in the Smiths’ upstairs study, the blue flicker of a TV behind the Nguyens’ shades, the low hum of a dryer venting into the freezing night. It wasn’t late, but it felt like something was ending everywhere at once.

I walked to my car without looking back and sat behind the wheel until my breath stopped sounding like an emergency. For ten years, my life had been divided into two seasons: Before Dad’s business failed and After. Before, he had the posture of a man who’d built his own scaffolding; After, he stood like someone who’d learned the sky can be convinced to fall if you explain yourself convincingly enough. Before, my mother called me on Sunday mornings to tell me about produce sales and ask if I’d met anyone nice; After, she called every time the electric bill read like a dare.

At twenty-four, when my friends were calculating 401(k) contributions and fighting over whose turn it was to buy the next round of cheap beer, I was wiring half my paycheck into a checking account that bore my name and my father’s shame. Autopay for the mortgage drafted from a subaccount attached to mine; the note was in his name, but the money belonged to the same number on every check stub with my signature. They said it was temporary. They said things would get better. I believed them for longer than someone like me should.

We were supposed to be a family. Messy, flawed, but real. That’s the lie we all agree to, sometimes: that love will eventually catch up to whatever damage outran it.

When the keys stopped vibrating, I put the car in drive and, for the first time in years, left without calculating who needed what first.

Part II: Strings Attached

Winter taught me to enjoy the way cold air insists you keep moving. I worked, I ate what fit in bowls, I slept in the apartment I’d been too cautious to call mine. It had a lopsided radiator that sounded like it had opinions and a neighbor below who practiced scales on a trumpet every evening, slow and proud, like he was teaching himself to breathe.

I had friends, though we’d downsized our version of each other over the years. Mia worked at the hospital and had eyes that stayed on you even when her phone vibrated with other people’s emergencies. Leo from the office trusted me with bureaucratic riddles and all the ways men pretend to be harmless. They had asked a thousand times if I needed anything and I had said no in a thousand different translations: I’m good. We’re okay. It’s temporary. Things are looking up. They weren’t lies, exactly. They were hope with a script.

When the roof leaked, I climbed a ladder and spread tar like frosting. When the dryer broke, I watched videos and learned the language of belts and lint and patience. When the mortgage payment hit like a quiet train, I told myself this is what good sons do. Mom called me her rock. Dad called me a man. The titles mattered more to me than what I was losing to earn them.

Then November arrived with its cheap sunlight and a woman in a beige coat standing in our driveway with a camera. I had come by with groceries and a plan to fix the sticking back door. The woman smiled and said she was there for the listing photos. For a second, I thought I’d misheard. She pointed to the email on her phone. Address, appointment, real estate agency logo so crisp it might cut you. “Congratulations,” she said, because in her line of work that’s often the safest assumption.

I stood very still. There are moments you can feel your life pull its own plug.

That night I confronted them. My parents sat at the table, the lamp painting everything the color of old pennies.

“Moving,” Mom said, careful but bright. “It’s a new start.”

“Without telling me,” I said. “Without including the person who’s been paying for your roof.”

Dad’s mouth tightened. “We don’t need strings attached.”

Strings. That’s what they called the transfer I had created, the one that kept the house from being a letterhead.

“You said temporary,” I said.

He shrugged, a movement so small it looked like a twitch. “Everything is, eventually.”

There are sentences you cannot answer because answering them would require erasing yourself. I put the milk in the fridge because habit is a gentle tyrant, put the bread on the counter because there’s a right place for bread, then I left.

When Mom shouted her line weeks later—Leave and don’t return!—I realized it was just the final white tile in a path I’d been following blind.

Here is the part I’m not embarrassed to admit: I didn’t cancel a thing. I didn’t call the bank. I didn’t log into autopay and set the fields to zero as an act of revenge that would make a certain kind of story taste right. I simply stopped transferring funds into the subaccount that fed the autopay that fed the mortgage that fed a house that no longer had a room with my name on it.

I didn’t even turn off the light as I left. I was efficient about it, and you can call that petty, but I call it respect for consequences.

Part III: The Visit

It took three weeks for the dam to crack.

First came the late notices—emails forwarded to me with the subject line “???” and no body, like punctuation could rescue a decade. Then the voicemails. Mom cried and told me I was breaking her heart. Dad didn’t cry—he’s from a time when men were taught that tears are a currency you’re supposed to save—but his voice had the rasp of a man who’d been on the phone with Hold too long.

“Son,” he said on the third message, “the bank’s calling. What’s happening?”

It’s strange how quickly your body remembers who it used to be. My finger hovered over the call back button. I could see the shape of us on the porch. I could hear him call me by the nickname he saved for Saturdays and car rides. I could taste the apology forming on my tongue like a reflex.

I didn’t call back. Some silence is cruel. This wasn’t that. This was a no that had earned a pension.

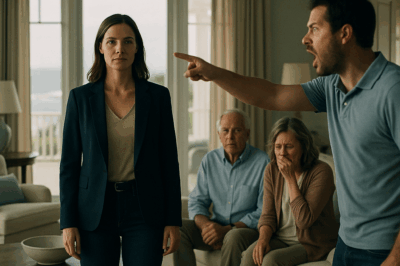

On day twenty-two, he came to my door. Through the peephole, he looked older than his age—shrunken, as if the house had been lending him mass and took it back. I opened the door because my mother’s sentence had been used on me, not him, and because I am not a man who learns meanness quickly.

He tried to sound calm. “Why’d you stop paying the mortgage?”

I leaned my shoulder against the doorframe because a body needs somewhere to put its weight when it’s choosing not to collapse. “Because,” I said, “you told me I wasn’t part of that house anymore.”

He blinked. Confusion skittered across his face, landed nowhere. Pride is a wild animal we invite into our living rooms and pretend we can domesticate; it eats whatever’s closest when it’s hungry.

“You said you didn’t want strings attached,” I continued, steady. “So I cut them.”

For a second, it landed. I saw it—the ledger in his head align, the list of every payment, every Saturday I didn’t go to the lake because there was a fence that needed fixing, each time I told myself vacation exists for people who have parents that know how to pay their own utility bills. You could watch him rewind the tape and discover the real movie.

“We’ll lose everything,” he said.

“You already did,” I said. I didn’t mean the house.

He stood in the hallway and became a silhouette of a man I recognized and didn’t. The door was heavier than it looked, but I closed it without barking my knuckles. He didn’t knock again.

The next day at work, Leo hovered at my cubicle like friendly fog. “You okay?” he asked, and the way he asked told me he’d heard the part of my voice that still carried a boy.

“Yeah,” I said. “I think I’m finally going to be.”

Mia came over that night with soup and the gentle badgering people use when they’ve decided to save you whether you like it or not. “You don’t have to set yourself on fire to keep anyone warm,” she said, a sentence I wrote on a sticky note and stuck on my laptop and then peeled off and stuck on my wallet and then stuck on my mirror because it kept being true in new places.

Weeks later, I drove by the old house. Grass high, orange foreclosure notice taped to the front door like a final exam everyone failed. Mom on the porch shouting with the exact pitch she’d used when she screamed me out of the front door; Dad not walking away because there was nowhere left to go. I didn’t feel triumph. Relief has a quieter mouth. I rolled my window down and let cold air come in and sit on my face like a hand. No music. No noise. The silence was not a punishment. It was a room.

Part IV: What a Life Looks Like Without a Bill You Didn’t Create

There is a special kind of lightness in the first paycheck you get to keep. It isn’t greed. It’s a new math.

I did simple things. I paid off my credit card the day the statement dropped and said out loud to no one, look at you. I bought flour that cost more than common sense because I wanted to know if bread could taste like not worrying. I changed the oil in my car before the sticker told me I had to. I slept in on a Sunday and discovered time moves differently when it isn’t carrying someone else’s panic.

I called the bank and removed my name from everything that wasn’t mine. I called the utility company and did the same. Each hold music was its own genre of remorse. “Are you sure?” one representative asked, earnest. “Yes,” I said, and didn’t explain because the explanation was none of her business and all of mine.

I found a therapist named Maritza who had a lamp in her office that made the room feel like late afternoon in a house that never had to lock its doors. She didn’t ask me why I stayed so long inside their storm. She asked me what weather I wanted to learn to forecast for myself.

“Quiet,” I said. “I want a life that isn’t always bracing.”

She nodded like I’d given her a grocery list. “We can get you that,” she said.

On week six, I took my first vacation in years. Not a plane. Just three days in a cheap cabin by a lake that remembered how to treat men gently. I read. I cooked badly and laughed and ate anyway. I walked until my body felt like a dog happy to be on a trail. I came home with a new coffee mug that wasn’t expensive but looked like someone made it with good hands.

At night, I stayed up and added numbers like joy. A savings account with a name that wasn’t Emergency this time. A line item in my budget called House (Mine) and I didn’t know what that looked like yet, but it felt like a good sentence. The budget stopped being triage and started being choreography.

Neighbors started to know my name—Mrs. Patel down the hall, who calls everyone beta and leaves tangerines at your door when she thinks you look paler than you should; Mr. Whitaker on 3B who complains about the mailboxes but shows up with a screwdriver and fixes them anyway; the trumpet player downstairs, whose mistakes got softer once I started tapping the beat on my desk and he realized we were a band.

Mom texted twice. “We’re staying with Aunt Jean for a while,” she typed, and then, “Could we talk?” I didn’t respond. Love is not a drive-through, and I didn’t have exact change.

Dad texted once. “I’m sorry.” No punctuation. I put the phone face down and let the sentence sit in the dark. Apologies are only useful if there’s a plan stapled to the back.

Mia said, “Do you want to drive past the house again?” and I said, “No,” and we drove to the next town and bought donuts the size of our palms and the color of a good bruise and we ate them on a bench until we had sugar in the joints of our fingers.

Two months after the foreclosure, I stood in a small, sunlit living room with a realtor who didn’t try to sell me anything I wasn’t already falling in love with. The place was a pocket: bedroom, living room, a kitchen that smiled if you looked at it too long. Cheap, by coastal standards. Mine, by an arithmetic I had earned. I put in an offer and wrote a letter that said, “I want to live in a place that forgives.” The seller circled my name and said yes.

On moving day, Leo and Mia carried boxes and yelled at each other about the right way to transport a television. We opened windows and let the city in. I held my keys—the new ones, brass with sharp teeth, cleaner than promises—and I remembered the ones I put on the counter and the way they sounded. Endings and beginnings make the same noise; it’s what we call them that changes their shape.

Part V: The Call That Didn’t Undo Anything

Dad called again on a Thursday when the sky tried on rain but decided to keep it for later. I recognized the number and felt nothing wild in my pulse, which is its own miracle. I let it go to voicemail. When he texted five minutes later—Can I see you?—I said, Coffee Saturday, 10. The café had windows that let you watch people decide the day they were going to have.

He arrived early and sat cornered by morning light. He looked like a man who understood that shame comes in white envelopes and silence. He stood when I approached and then didn’t know whether to hug me and settled on standing still. I sat. We didn’t talk and then we did.

“I’m sorry,” he said. This time with a period.

“For what?” I asked. Sometimes specificity is the only way a bridge can be built.

“For letting you carry us,” he said. “For letting her talk to you like that. For telling the world I didn’t need my son when I was alive because I was too proud to say I did.”

He was not a good man pretending to be bad or a bad man pretending to be good. He was my father. That’s messier. He wasn’t asking for money. He was asking for a language we hadn’t spoken to each other without fear in a long time.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

He stared into his coffee like a man who has been given a pool and doesn’t know if he remembers how to swim. “Working nights at the warehouse,” he said. “I took a budgeting class at the library. I have… two months sober.”

I sat with that. Pride doesn’t always bark. Sometimes it waits to be invited to the table. “Good,” I said.

“I’m sorry,” he said again, and I believed it.

“I can’t fix this,” I said, and he nodded like he’d hoped I would say that instead of the opposite. “But if you keep doing the things you just told me, we can keep having coffee.”

He exhaled. It sounded like winter leaving.

We didn’t talk about Mom. I didn’t ask where she was staying now, whether the words she’d used on me had turned on her tongue like a boomerang. I didn’t need narrative symmetry to make my life livable.

When he left, he didn’t try to hug me. “Next Saturday?” he asked at the door.

“We’ll see,” I said, and he understood somehow that those words were a possible yes and not the polite version of punishment.

Outside, the city had decided on rain after all. I put my hood up and walked home the long way, past my old apartment, past the mailbox that used to rattle like a warning when the ones with windows arrived, past the tiny park where kids in winter hats learn how to accept gravity and try again. I unlocked my door and walked into a room that smelled like rosemary and dust and a beginning I had orchestrated.

That night I cooked, badly but proudly, and I opened a window because cold air is still a friend. I ate at my small table and wrote a new budget for a life that didn’t require me to translate love through money. I added a line for gifts that didn’t taste like guilt. I added a line for travel to a town with a lake that had been kind to me once. I added a line for therapy and called it “weather,” because that’s what we were doing there—learning to forecast, learning to pack for a storm, learning to go outside anyway.

Mom texted the next morning. A simple “Thinking of you.” I stared at it long enough to memorize the exact shade of blue around her bubble, and then I set the phone face down. I did not respond. Not because I am cruel. Because I am learning to speak a language where boundaries are grammar and love is the sentence and not the excuse.

Weeks later, a letter arrived at my new address, forwarding caught up like a good dog. It was from the bank; habit made my stomach tense. I opened it and laughed quietly at myself: an advertisement for a savings account with a ridiculous interest rate and a more ridiculous name. I tore it in half and recycled it and forgave my body for flinching.

On the first warm day of spring, I planted basil in a pot on my small balcony and put it in a square of sunlight like an apology to every plant I’d ignored for lack of time and attention. I breathed. It smelled like the inside of a summer I hadn’t yet written.

Sometimes, when the radiator hisses and the trumpet downstairs finds a note he’d been chasing, I hear the keys on the counter, the sugar jar gavel. End. Then I hear another set of keys—mine now—on a new counter, tapped lightly, not as a verdict but as a beginning.

They wanted me gone. I left. They wanted no strings attached. I cut them. I thought the sound of severing would be loud; it wasn’t. It was the quiet that followed that told me who I was.

I roll the windows down when I drive now, even in cold. No music, no noise. Just air and the certainty of forward. The last debt I ever paid was the one they taught me to believe I owed: my future for their comfort. I paid it in full when I stopped. And the receipt looks like my life, fitting me, finally—messy, flawed, but real.

Part VI: The Ledger of the Past

When Maritza asked me to bring “artifacts” from before the collapse, I thought she meant bills. She meant photographs. I dug them out of a plastic tote I’d labeled STUFF in a panic after a pipe burst in my parents’ basement years ago. There were birthdays where the cake leaned, Halloweens where my costume looked like an apology, and a photo of Dad the year the shop opened, standing in front of a freshly painted sign with his name in font he’d sketched on napkins. He was thinner and wider at the same time—thin with hunger for a future, wide with the way men become architecture when they’re building something from nothing.

“What did you learn from him before the fall?” Maritza asked.

“Everything that matters,” I said. “And one thing that almost killed me.”

“What’s that?”

“That you prove you’re a good person by how much weight you can carry without asking for help.”

Maritza nodded and said nothing for a while, the way good therapists make room for a truth to take off its shoes and sit down.

I told her about mornings in the shop, the smell of metal filings and coffee that forgot to be fancy. How Dad showed me how to cut lumber by measuring twice and cutting once, and how Mom showed me how to cut feelings by measuring nothing and cutting always. They were not villains in this story. They were just human beings, underfunded and overproud, raising a son who thought the only way to keep love was to staple himself to other people’s emergencies.

“Your mother,” Maritza said gently. “What story do you think she was telling herself the night she told you to leave and never come back?”

“That I had become the ledger,” I said. “Not the son. A balance sheet with a pulse.”

“And now?”

“Now I’m a person again,” I said. “With a ledger of my own.”

We stayed late that evening. On the way home, the trumpet player downstairs was working on a new song—something hopeful that still lost its way around the bridge. He stopped, started again, and then nailed it. I laughed alone in my kitchen. He didn’t know it, but we applauded together.

Part VII: The Auction

Foreclosure doesn’t fast-forward like the movies. It drags. A notice. A notice about the notice. A date that changes twice because the courthouse staff is human and county software is not. I told myself I wouldn’t go. I went.

Courthouse Room B smelled like damp paper and impatience. A man in a too-tight suit read parcel numbers like prayers he didn’t believe in. Investors with legal pads wrote on top of each other’s writing. People in hoodies stared at shoes. A mother bounced a baby who wouldn’t stop reminding us what oxygen is for. When our address gurgled through the man’s throat, I didn’t flinch. The opening bid was less than my first year of payments. Someone raised a paddle. Someone else scratched their ear. Gavel. Sold.

There were no violins. But when I walked out, spring had finally committed. On the courthouse steps, two sparrows argued about a crumb. It felt like permission to live again.

That night I wrote a letter I did mail—to the address of the house I now owned. To myself.

You did not fail. You stopped. You chose a life that fits. Wear it every day without apologizing for how good it feels.

I stuck it with a magnet to my new fridge and left it there until the corner curled and I had to tape it, which made it better somehow.

Part VIII: The Visit That Wasn’t a Reckoning

Two months into the new place, Mom texted again. Can we meet? No punctuation. No exclamation points—the punctuation of her optimism and her fear.

We met at a quiet diner off the highway where waitresses call you honey and the ketchup bottles are already sticky. She looked smaller and younger and older, a trick grief plays. I slid into the booth and waited. She fiddled with a paper napkin until it became confetti.

“I didn’t want to sell,” she said. “He did.”

“You told me to leave,” I said. I wasn’t asking a question. I was laying brick.

“I know,” she said, and those two words opened a door I didn’t trust but could see through.

She told me pieces I knew and pieces I didn’t: how the bank manager who used to bring cookies when she was a teller retired and the new one spoke in acronyms; how Dad believed the summer would bring contracts it didn’t; how pride makes people deaf even when they want to hear. How she grew up with a father who only knew love as a condition she could fail and how that made “get out” sound like protection, even when it was poison.

I waited for the part where it became my fault. It didn’t come.

“I’m… sorry,” she said, small but precise. She looked at my face the way mothers look at babies when they’re not afraid of breaking them. “I thought love meant protecting him from hard things. I forgot you were a person, not a resource.”

“Thank you,” I said, because when a person offers the right apology, the politest thing you can do is accept it clean.

“I want to earn coffee,” she said. “Later. When I’ve figured out who I am when I’m not rescuing him badly.”

“Later,” I agreed. I left with pie in a to-go box and a small hope I did not admit to.

Part IX: Building Something That Doesn’t Collapse

Leo and I decided to build bookshelves with our own hands because YouTube had convinced us we were capable men and because I needed a place to put the secondhand poetry I’d been buying like bread. We measured wrong twice. We cut once badly. We swore softly because his niece was visiting and had ears like law enforcement. By hour five, the board settled into the bracket and the bracket decided to be helpful. We stood back and admired something straight that had not started that way.

“You ever think about kids?” Leo asked, because building things makes men consider versions of themselves they still have time to become.

“Sometimes,” I said. “But I think about not raising a mortgage more.”

He nodded. We didn’t joke our way out of the honesty. We held it for a minute, then moved on to sanding. That felt like practice for being the kind of men we want to be.

I put Dad’s old hammer—the one with electricity stains and a handle that fits my palm like a handshake—on the shelf when we finished. Not as a shrine. As a tool that belonged where it could be reached without hurting me.

Part X: The Call from Aunt Jean

Aunt Jean is the family’s emergency contact. She can coax a soufflé and a confession out of a person using the same voice. She called one evening with her newsreader tone.

“He’s trying,” she said.

“I know,” I said. “We have coffee.”

She took a breath that said she’d had to choose her words twice. “She is, too.”

I leaned against the doorframe and waited.

“She’s… in a group. Women who’ve been angry for twenty years and tired for twenty-one. She got a job at the library.”

“The library?”

“They pay her to tell kids not to run and grown men to stop whispering,” she said. “It suits her.”

We didn’t solve anyone that night. We didn’t have to. It felt good just to know other people were being supervised by something other than my sense of duty.

Part XI: A Housewarming with Only Furniture

When the boxes were gone and the plants had survived three weeks without acts of God, I hosted a housewarming. No charcuterie board in sight—just pasta and salad and a cake from the grocery store iced with congratulations to Tammy because it was discounted and I think Tammy is probably out there doing her best.

People brought ridiculous gifts: a doormat that said THIS PLACE HAS RULES, a screwdriver set that had twenty more pieces than any one person could need, a candle that made the room smell like rich people’s laundry. Mia cried once and pretended not to. Leo stood in the kitchen doing stand-up about his failed shelf career even though the shelves were right there working.

Halfway through the night, a knock. I opened the door to find Dad on the stoop with a plant in a terra cotta pot and the look of a man who had asked a stranger which one doesn’t die easily. A snake plant. Good choice.

“You told me once you liked green things,” he said.

I took it. Behind him, the hall light made him look like he’d been cut out clean against something bright. “Come in,” I said. He did. He hugged Leo like they fought on the same side of a war. He told Mia she reminded him of a neighbor from his childhood who had saved a squirrel. He did not make it about me. He made it about being here.

When the party slid into dishes, Dad rolled up his sleeves and found the rhythm we’ve always had—pass, rinse, dry, stack. He didn’t say sorry. He didn’t explain the past. He said, “Need anything else?” and I said, “No,” and we both meant it.

After everyone left, I put the snake plant on the shelf next to the hammer and the letter to myself. The house had a corner now that understood who I am.

Part XII: The Thanksgiving I Didn’t Expect

I had planned to travel for Thanksgiving—something obscenely tourist like a train ride through New England cliches. Two weeks out, Aunt Jean texted a photo of a turkey that could solve hunger and wrote: It would mean a lot to him if you came. And her.

I do not owe anyone my holidays. But I owed myself the chance to see if peace can hold more than one person at a table without breaking.

We ate too early, the way families do when they like the excuse to eat twice. The new place Aunt Jean had found for them was small and tidy, two chairs by a window that looked out on a tree that had not decided yet whether to shed or keep. Mom had set the table with a care that felt like a prayer. Dad had made the gravy without lumps, which is miraculous and should be recognized in national registries.

We did not revisit that night. We did not say words like foreclosure or mortgage or leave. We talked about Aunt Jean’s neighbor who insists on singing to his trash cans at 6 a.m., and about a show none of us had seen but all of us had opinions about, and about the boy in Mom’s story hour who told her leaves are dead flowers and how she had laughed until she realized he might be a poet.

Halfway through, Mom stood to refill my water and paused behind my chair. She set a hand on my shoulder, only for a second, and squeezed. It landed in my bloodstream like medicine.

On my way out, Dad walked me to the door. “Next Saturday?” he asked.

“Next Saturday,” I said.

Driving home, the radio landed on a station playing a song Dad used to hum when he worked at the bench. I sang along and was surprised my mouth knew the shapes. I did not cry. Not from sadness anyway.

Part XIII: The Letter to the Boy I Was

On the anniversary of the night I left the keys on the counter, I wrote a letter to the version of me who was still waiting to be chosen as much as he was useful.

Kid,

You did your best with a rulebook no one gave you. You were brave in boring ways, which is the only bravery that lasts. You don’t have to be the answer to every question in a house that refuses to ask the right ones. You can leave without becoming a person who loves less.

When they tell you to go, go. But don’t leave yourself behind. He needs to see the place you built for him.

P.S. The trumpet player learns the bridge. You will too.

I tucked the letter in the plastic tote labeled STUFF, now amended to STUFF + PROOF.

Part XIV: The Ending People Don’t Believe in Because It Isn’t Loud

In May, the trumpet player moved. I know because the scales stopped and the apartment below turned into the muffled rumble of a couple who cook together. He left a note on the corkboard by the mailboxes: Thanks for clapping. I hadn’t been that loud, but I appreciated the assumption.

Dad got promoted at the warehouse. Mom started bringing home books about minerals and letting kids knock them together to hear different clinks, the sneaky way she teaches science. Their place smells like coffee and possibility when I visit. They do not ask for money. I do not offer. We split the check.

I saved enough to upgrade my car to one whose check-engine light does not believe in performance art. I planted herbs on the balcony and learned basil likes to be touched, that mint will colonize if you let it, that rosemary takes its time like someone who knows they’re worth the wait. I learned to bake bread that won’t embarrass itself in front of strangers. I learned that I snore a little when I sleep on my back and that the solution isn’t shame; it’s a pillow.

Mom and I had coffee without Aunt Jean for the first time. She told me a joke that made me spit mine and apologized for the spray and then didn’t apologize for the story. She told me she’s learning how to be a person whose first instinct isn’t fear. I told her I’m learning how to be a person whose first instinct isn’t rescue. We laughed like two people sharing new grammar.

Sometimes I drive past the old street to remind myself the world did not end there. The house is painted a different color. The new owners put up a small basketball hoop and a string of lights on the porch. A kid’s bike lies in the yard like a fallen promise that will be picked up. I am not the ghost at that address anymore. I am a passerby, allowed to smile.

On nights when rain tries to play the windows like an instrument, I stand in my kitchen and tap my keys on the counter. Not as a gavel. As a metronome. The beat I keep now is my own.

They told me to leave and not return. I did. Dad asked why I’d stopped paying. I told him the truth, and for once, we let it do all the talking. Nothing exploded. Everything changed. The last debt I ever paid was to myself: the promise that I would not finance someone else’s denial with my future. Paid in full.

And still, without resentment, with a boundary instead of a wall, I keep a second mug in the cabinet. Not because I’m waiting for someone to come claim it. Because the life I built has room. For coffee with Dad on Saturdays. For Mom’s library stories. For friends who show up with tiny screwdrivers and enormous opinions. For me, at my own table, hands washed, appetite honest, no longer eating around the parts of my life I can’t chew.

The silence that followed me out that night is not behind me anymore. It’s beside me, an old friend that knows when to speak and when to sit with me while I listen to everything I can finally hear.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Mistress Attacked Pregnant Wife in the Hospital — But She Had No Idea Who Her Father Was

Mistress Attacked Pregnant Wife in the Hospital — But She Had No Idea Who Her Father Was Part I…

An Unknown Number Called Me It Was His Ex What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew

An Unknown Number Called Me. It Was His Ex. What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew Part…

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law Part I —…

I GIFTED MY PARENTS A $425,000 SEASIDE MANSION FOR THEIR 50TH ANNIVERSARY. WHEN I ARRIVED, MY MOTHER

I gifted my parents a $425,000 seaside mansion for their 50th anniversary. When I arrived, my mother was crying and…

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am Part I:…

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side? Part I — The Unicorn…

End of content

No more pages to load