Mom Said, “We’re Doing Thanksgiving With Just The Well-Behaved Kids — Yours Can Skip This Year.” My Daughter Started Crying. I Texted Back, “Understood. I’ll cancel my card for the event.” They Kept Laughing, Sending Selfies At The Table — Totally Unaware Of What Was About To Happen NEXT…

Part 1

The text arrived while I was folding clean socks into careful pairs, the house quiet except for the scissors snipping next to me. My daughter, Eva, sat cross-legged on the rug, tongue caught between her teeth in concentration as she cut paper leaves for a school “thankful tree.” She held up a maple cutout and announced, with the solemn pride only seven-year-olds have, “I’m thankful for Grandma’s cookies.”

I smiled at her, then looked down at my phone.

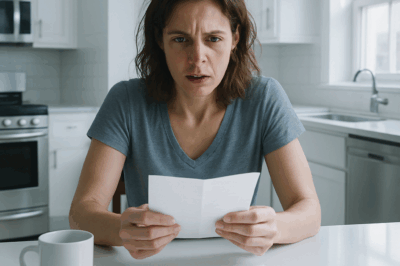

We’re celebrating Thanksgiving only with children who behave well. Your daughter can skip it this year.

That was it. No hello. No context. No emojis to dress the cruelty like a joke. Just a sentence that iced my fingers to the phone.

I read it three times, hoping the words would rearrange into something forgivable. They didn’t. In the reflection of the screen, I caught my own face hardening in a way that made me think, If she looks up right now, she’ll learn something I’ve tried to delay teaching her.

Eva did look up. She saw me, saw the phone, saw the crease between my eyebrows. “Is Grandma coming for Thanksgiving?” she asked, hopeful, a leaf cupped in her hand like an offering.

“No,” I said. I didn’t mean to, but I turned the phone toward her. She read the single sentence, and her mouth went slack. She didn’t speak for a long beat. Then, very carefully, she asked, “Did I do something wrong?” When I shook my head, she started to cry—not the big, loud kind that demands rescue. The quiet kind. The kind that tries not to be a problem.

Something in me flipped over and landed with a final click. It didn’t feel like fury. It felt like a permanent understanding, the sort that redraws a map in your head. My parents had never wanted her. Maybe they’d never really wanted me either. Only the version of me who cost them nothing and nodded on cue.

I sat with Eva until the sobs shrank to shivers. We listed three ridiculous things we were grateful for (pancakes for dinner, socks that match, a neighbor’s cat who thinks our porch is his kingdom) until her breathing smoothed. Then I went into my room, shut the door, and typed a reply.

Understood. I’ll cancel my card for the event.

Because here’s the part my mother always edited out of her holiday stories: for the last three years, I had paid for everything. The turkey. The pies. The rented heaters when November remembered to be cold. The string lights my mother pretended she “found in the garage.” The fancy place settings and the professionally arranged “herb centerpieces” she posted on Facebook as if rosemary had decided to lie itself down in a ring for her alone.

I make good money as a consultant. I never minded helping, not when I believed help was what we were doing together. I’ve covered bills for families who didn’t know me beyond a case number; of course I’d cover a holiday for the people who raised me. It had felt like love.

Staring at my mother’s text, the math shifted. Love didn’t look like this. Love didn’t exile a seven-year-old by text.

I opened my laptop and began to cancel. The catering. The rentals. The florist. The wine delivery scheduled for mid-morning because my father likes to open a bottle “to breathe” while the parade’s on. A few places charged late fees. I accepted them the way you accept a bruise you know will heal.

I didn’t say anything else to my parents. They’d told me exactly how much my daughter—and therefore I—mattered. I took them at their word.

Thanksgiving morning, Eva and I stayed in pajamas. I made pancakes in the shape of leaves because she’d left her paper ones scattered like confetti. We ate at the coffee table, ridiculous amounts of syrup puddling, our laughter a kind of replacement music. At eleven, the family group chat lit up as if nothing had shifted.

Table’s gorgeous this year! my mother wrote, posting a picture of candles and cloth napkins folded like doves.

Ready for the feast! my brother, Ben, added, with a selfie of him and my dad, beers in hand, grins wide.

My sister-in-law added a boomerang clink of glasses. Then another photo: a toast “to family that behaves.” The caption was precise and cruel. It landed like a pebble thrown at a window you’d already decided to replace.

I put my phone on Do Not Disturb and taught Eva how to perfectly flip a pancake. We built a fort with blankets and read a chapter of The Princess Bride in our best pirate voices.

At 2:45, a text slipped through anyway—Ben, somehow on a separate thread.

Hey, is the food coming later this year or…?

Three dots. Then, from Mom: Nothing showed up. What’s going on? The caterer isn’t answering. The florist says we’re not on the schedule. They’re saying the card was canceled.

I set the phone back on the counter. The turkey sandwiches I’d grabbed from the deli the day before tasted like peace—thin slices, a smear of mustard, potato chips that shattered like bright applause.

They kept sending selfies. Toasts to tradition. Posed smiles in that dining room. The pictures got fewer as the hours thinned, faces turning tight, cheeks hollowing with hunger and irritation. If there was a photo of the moment they understood, no one sent it.

That night, after Eva fell asleep under our blanket fort, I stood at the window with the lights off and traced the shape of my life with a finger on the glass. I hadn’t planned revenge. I had simply stepped out of a role I’d been cast in without an audition.

But the second act had already started without them noticing. Three months earlier, a letter addressed to my parents had been delivered to my house by mistake. The envelope bore a credit union’s logo I didn’t recognize. Inside: notices about missed payments on a loan co-signed by my parents for Ben’s new BMW. The line that made my stomach drop wasn’t the amount. It was the collateral.

The property used to secure this loan is the residence located at—

My parents’ address. My childhood home.

I’d called my mother then, voice neutral. She had breezed past it. “Handled,” she said. “Don’t fuss.”

She hadn’t handled it. They were sitting in a house they didn’t quite own anymore—raising glasses inside a story that was no longer theirs.

On Monday, Ben called me twice during a meeting. I let it ring. He texted: Are you free? It’s important. Not about Thanksgiving. Later, my mother called. Then my father. The sudden urgency was a familiar flavor: we are a family when we need something you can provide.

That night, I listened to a voicemail from my mother. Her voice wasn’t cold. It was tired. “We have a situation with the bank. Temporary. Could we discuss…help? Something about the mortgage.”

I already knew. I’d known since the letter. The BMW had become a vine, and the vine was circling the house.

I did not answer.

For three days, their calls stacked like plates. My father texted a long message about how family sticks together and how he knew I wouldn’t let something small ruin everything. Small. He called the possible loss of a 27-year home small. He called the first place Eva had ever slept away from me small. He called the physical proof of every sacrifice they’d insisted I make small.

That’s the thing about people who think they’ve reserved the right to define reality: their words stop matching the world.

In the end, I did help.

I wired the money directly to the credit union. Not to my parents. I sent no announcement. I let them sweat in the waiting room they’d asked me to sit in my entire life.

Three days later, a letter came to their house: foreclosure proceedings withdrawn. They called me an hour after the mail usually arrived, both of them on speaker, their voices frosted with rehearsed gratitude. My mother even said she wanted to take Eva Christmas shopping. She used a tone she saves for the cashier she wants to flirt with for a discount. It sounded like generosity.

I wanted to believe them. It’s a stubborn truth: children want their parents to be different even when those parents are telling them who they are in fluent, repeatable sentences. I said yes. I told myself it was a turning point.

It wasn’t.

Part 2

Eva wore sparkly boots that gave her blisters and a sweater with a reindeer knitted across the front. She’d made a list of gift ideas with little doodles next to each one: a book with a dragon that isn’t scary; socks with cats; a paint-by-number kit with a sunset; a small pink whistle “for emergencies and also fun.” She had folded the list and slid it into her tiny purse with four dollars of allowance money and a generous heart.

She stood at the window, breath fogging the glass, counting “Mississippi” between looks outside.

When my parents pulled up, my mother honked once, precisely. My father didn’t get out; he doesn’t open doors unless a camera is watching. Eva grabbed her purse and spun in a circle in the entryway, nervous energy peeking out like the hem of a petticoat. I crouched and kissed her forehead. “You call me if you need me,” I said. “For any reason.”

“I know,” she said, brave.

They were gone for four hours.

When they brought her back, she came inside without a word and went straight to her room. My mother stood on the threshold like a delivery person who needed a signature. “The mall was so crowded,” she said, tone airy. “Hard to find anything.” She didn’t meet my eyes.

On Eva’s bed: a small paper bag. Inside: a rubber snowman keychain.

Later, when the house was dim and quiet, I heard the unmistakable sound of someone trying not to cry. She had buried her face in the pillow and was doing that small, swallowing sob designed to keep an adult from obeying their impulse to fix everything.

“They didn’t take me shopping,” she said when I sat beside her and put a hand between her shoulders. “They bought presents for everybody else.”

Presents for her cousins: outfits, toys, a gold bracelet “for the baby to grow into.” She had watched them choose carefully. When she asked if she could pick a small toy, my mother said, “We’re not buying you anything. We’ve already spent too much.”

On what? I asked.

“On real grandkids,” she whispered, repeating words she didn’t understand. And then, in the food court, my father: “At least we don’t have to worry about her acting out in public this time.”

Eva hadn’t cried in front of them. She’d folded her hands in her lap and followed. Obedient. Well-behaved. The kind of child they said they wanted.

I didn’t sleep that night. Not from rage; from a grief so cold it felt like being packed in snow. There’s a moment when you admit the story will not turn. The page you’ve hoped to read next doesn’t exist. My parents would not begin to love my child in the way children are supposed to be loved—without conditions, without scales, without using the word mistake in a sentence about someone breathing.

I stopped imagining an arc where they picked her up and took her to a bookstore and told her to choose two, any two; where they took a photo together in the Santa line and bought hot chocolate and built a memory that wouldn’t bruise when she touched it. I stopped imagining their change and started planning our exit.

Two weeks before Christmas, my father arrived without texting first. He knocked with the old rhythm he used on my bedroom door when I was sixteen and had the audacity to close it.

I opened the door because I wanted to see his face and know, in my bones, that I was not making him up.

“Hey there,” he said, smile switched on, eyes not softening. “How’s the little one?” He said it like her name might be just out of reach, tucked under the car keys and the again-unpaid tolls. Then he got to it. “We need a hand.”

Of course they did. The BMW had accumulated fines, toll violations, and insurance penalties, all in my father’s name because helping Ben had included tying his own ankle to a brick. “The DMV is threatening to suspend my license if we don’t clear it immediately,” he said. “Not Ben’s fault, you know how notices go to old addresses. The system punishes families who fall on hard times.”

He wanted “a few thousand.” He made a joke about early inheritance. He said it like he was offering me an opportunity to audition for Good Daughter again, as if the role was vacant and I’d been missing the stage.

Something inside me snapped so cleanly it felt like relief, like a bone cracking and setting itself right.

“No,” I said.

He blinked. The word didn’t sound real to him coming from my mouth. “We’re family, Grace. You don’t turn your back on family.”

“Does Eva count as family?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. He looked down and back up as if the question were a trick.

I stepped outside and closed the door behind me so Eva wouldn’t hear. “This is the last time we’ll have this conversation,” I said. “You and Mom need to stop pretending you haven’t spent the last ten years making sure my daughter knows she is an outsider in a room she owns the right to be in.”

“You’re twisting things,” he said. “You’re too sensitive.”

I didn’t argue. I’d wasted too many words already. “Go,” I said. “Don’t knock again.”

He waited ten seconds like he was letting me reconsider, the way he used to do when I asked for a different college major or to skip a party thrown by his friends’ children with last names like country clubs. When I didn’t rescind the no, he walked down the steps without saying goodbye.

The next day, my mother sent one line:

We always knew you’d punish us for not loving your mistake.

It sat on my screen, black letters on white, and in the space between one heart-beat and the next, whatever filament of hope had kept me plugged into them burned out. There it was in writing: the thing they’d said with a thousand small cuts, now carved into a sentence so plain it could be framed.

I blocked my parents. Their numbers. Their emails. Their social accounts. I blocked Ben and his wife. I shut all the windows they liked to crawl through.

The silence that followed for two weeks wasn’t peace. It was a pause. I kept expecting a letter to slip under the door, a neighbor to call with “You should hear them out,” a cousin to suggest “meeting in the middle” as if the middle wasn’t the very place they’d built to make us small.

Then, after New Year’s, my aunt—my mother’s sister—called from a number I didn’t recognize and left a voicemail about compassion. “They’re not doing well. Try to remember they’re human.” She didn’t know about the text. She didn’t know how long the harm had been stacking. I didn’t call her back.

An email from Ben appeared with a subject line: We need help. I didn’t open it. Then a letter arrived from my mother, five handwritten pages. The first four were dresses: excuses stitched from sentimentality. They “struggled to connect with Eva because she didn’t feel like the rest of the family.” They “weren’t ready to be grandparents.” They had “made mistakes.”

Mistakes: the word people choose when the truth would choke them.

Near the end, the dress fell off. There was a second mortgage. The payment I’d made before had not fixed the foundation. The bank had restarted proceedings. This time, there was no thirty-day cushion. The auction date was set for forty-five days. She wrote that the house was “our legacy,” that I “shouldn’t let emotions cloud judgment,” that I should be “bigger than this.”

I folded the letter and slid it into a drawer so Eva wouldn’t see it in the trash. That night, I sat Eva down on the couch. I told her we wouldn’t be seeing Grandma and Grandpa anymore. That some people don’t know how to love in a way that doesn’t keep score. That it’s okay to walk away from people who share your blood if they keep cutting you with it.

“Did I do something wrong?” she asked again, as if repetition might change the answer this time.

“No,” I said. “You existed. Sometimes that scares people who never learned how to be soft.”

She nodded. “Can we have spaghetti?” she asked, practical grace embodied.

We made spaghetti. We put whipped cream on store-bought brownies and declared it gourmet. We watched a movie and stayed up too late. When she fell asleep on my lap, the quiet arrived—not the brittle silence of holding your breath for the next blow, but the kind that comes when you finally set something heavy down.

Part 3

Three weeks before the auction, my doorbell rang. Through the peephole: my parents, side by side, the way they stand in photographs at fundraisers. My mother held a folder—paper’s battle armor. My father looked older and, for the first time, not entirely certain of the story’s ending.

I didn’t open the door. I watched. They rang again; they knocked; my mother said my name in the tone she used to call me in for dinner when we still pretended to be a family that ate at the same table most nights.

Eva came down the hall. “Should I get it?” she whispered.

“No,” I said. Just that. No explanation required. We turned on music in her room. We danced a silly, quiet dance.

When I came back, they were still there. I opened the door just enough for the screen to hold its thin line between us.

“You can stop asking,” I said. “It’s over.”

My mother started with the bank again. Steps taken. Misunderstandings. Papers that would explain everything if only I’d read them with the right eyes. My father didn’t speak this time. He studied the porch floorboards to find a splinter to blame.

“I don’t care about the steps,” I said. “I care that you told my child she doesn’t belong. That you told me my daughter is a mistake. That you’ve dressed cruelty as standards and called it care. I helped when I shouldn’t have. I gave you every chance to choose us. You chose a car and an image and a son who learned to hand you his consequences in pretty wrapping paper.”

They didn’t argue. Not because they agreed—because they finally understood how little oxygen was left for the fire they were trying to start.

“Let her write us letters someday,” my mother said, tears hanging on her eyelashes like ornaments. “So she doesn’t forget us.”

“You made sure she won’t,” I said. “Not the way you think.”

I closed the door.

Nineteen days later, the house sold. I didn’t watch the auction. I didn’t refresh the listing. I only knew the date because my mother had scratched it into the corner of her letter. Someone else would arrange furniture in the living room I once built blanket forts in. Someone else would paint over the ding in the hallway where I knocked a laundry basket into the wall when I was fifteen and rushing out to a life that suddenly felt possible. Houses forget you faster than you think. But they also stop being the place where a story keeps you trapped.

They moved in with Ben. Of course they did. He’d always been their favorite. Maybe now he could be their lifeline, too. Maybe he would learn that lifelines tangle when you tie them to people who believe gravity is optional.

Eva didn’t ask about them anymore. Not once. Children are not resilient because they bounce back without bruises; they are resilient because they learn to find joy in rooms where adults stop dropping glass. It’s an unholy skill. I would have spared her the need to learn it. Failing that, I would be the parent who made the room soft.

I didn’t tell her everything. Not the ugly additive of “real grandkids.” Not the fact that her grandparents had mortgaged their home for a second car and then had the nerve to lecture me about responsibility. She didn’t need those tastes in her mouth. I gave her this truth instead: you are loved on purpose, without condition, and anyone who doesn’t join that project loses access to us.

I changed her bedtime prayer at her request. We added a line: “Thank you for people who choose us.” She said it each night with a seriousness that seemed older than seven.

There is a peculiar emptiness after a decision that reorders your days. People expect fanfare or collapse. What came was practical. I called my bank and opened a college savings account in Eva’s name. The money I’d sent to stop a foreclosure became the seed for a future my parents would never claim as theirs. I rearranged our living room—not because of ghosts, but because the couch had always fit better under the window. I fixed the leaky tap my father used to promise to fix when he came over “next weekend.” I taught Eva to ride a bike in the cul-de-sac, running behind her and letting go when she didn’t know I had because some lessons deserve surprise.

On Sundays, we began volunteering at a community kitchen. The first time, Eva held the ladle with two hands, tongue caught between her teeth the way it had been when she cut those paper leaves. “Say hello, look people in the eye,” I whispered. “Everybody likes to be seen.” She served a man with a tattoo of a bird on his wrist, and he said, “Thanks, kiddo,” like it mattered. Eva glowed all the way home.

Aunt Maggie—the one who called about compassion—read the weather and chose us. She came over with a casserole that didn’t taste like pity and told Eva stories about my great-grandmother who swore at sewing machines and taught all her daughters to use tools not just recipes. “She owned a hammer,” Aunt Maggie said, tapping the table for emphasis. “A real one.”

“What did she build?” Eva asked, eyes bright.

“Exits,” Aunt Maggie said. “And shelves. And a kitchen table sturdy enough to hold four generations.”

We made new traditions with the neat stubbornness of people refusing to let someone else’s meanness steal an entire season. In February, we hosted a “halfway to spring” dinner where everyone we loved wrote something kind about someone else at the table on a card and then folded it into their napkin for later. In April, we planted marigolds and tomatoes in planters on the balcony because I wanted Eva to see something thrive in dirt we tended. In June, we camped in the living room and told ghost stories where the ghosts got jobs and therapy.

Sometimes, late at night when dishes were stacked and the apartment hummed its small, dependable hum, I caught myself reaching for my phone out of sheer old habit—waiting for a message that would require me to drive across town and do something that would be called helpful and feel like erasure. Then I’d remember: I had thrown the switch. The light that used to beckon people who only showed up with empty hands was off.

Part 4

If you want a ceremonial ending, you won’t get one from me. My life did not clap its hands together and declare, “There, that’s solved.” It simply kept moving in the direction of what I chose.

In March, Eva won a reading prize at school. She stood on a low stage in the multipurpose room while twelve parents and three siblings clapped too loudly. The principal gave her a certificate and a paperback. She scanned the crowd for me, found me, and lit up in a way that made my ribs feel correctly spaced. After, she asked, “Can we mail Grandma a picture?” The question landed without pain. It was curiosity, not a test.

“No,” I said gently. “Pictures are for people who show up.”

She considered that and nodded. “We can give one to Aunt Maggie.”

“We can,” I said.

In May, I got a promotion. More clients. More responsibility. A raise that made the numbers in my budget stop looking like a tightrope and start looking like a sturdy bridge. I bought Eva a secondhand piano with a middle C that sticks unless you press it like you mean it. She played “Twinkle, Twinkle” as if the stars were listening.

In August, a certified letter arrived addressed to me. I let it sit on the counter all day. After dinner, I opened it. The handwriting on the enclosed note was my mother’s, strained. The letter said they were moving again. Ben’s apartment had proved too small for three adults, two babies, and a dog who deserved better than any of them. They were going to stay with a “friend from church upstate” for “a while.” She wrote that she had seen a photo of Eva on my cousin’s social media and that she looked “grown.” She wrote that she prayed for our family every day. She did not ask for money. She didn’t apologize. It was the kind of letter you write when the story you’ve been telling turns into static and you reach for faith because you’ve run out of control.

I put the letter back in the envelope and slid it into the same drawer as the other one, not to keep it safe, but so I could finish washing dishes without seeing it. Later, I took both letters out to the building’s metal bin and let them go. Paper burns faster than you think. It curls into itself and the words blacken and lift like smoke that shouldn’t have existed. I didn’t watch until the end. There is mercy in deciding not to memorize destruction.

On the first cool Sunday of October, Eva and I hiked a short loop trail that smells like pine and something sweet you can’t name. She collected leaves for a new thankful tree at school. When we stopped for water on a rock that had warmed itself in full sun, she said, so matter-of-fact it startled me, “Our Thanksgiving is just us this year.”

“Unless we invite people who choose us,” I said.

She grinned. “Aunt Maggie. Mr. DeLeon from the community kitchen. Maybe Ms. Patel who brings the pumpkin pie with the leaf shapes on top?”

“Done,” I said. “We’ll set the table with the good plates and mismatched forks.”

“Can I make place cards?” she asked.

“Yes. Make them in shapes.”

“Leaves?” she said, mouth already deciding on the color.

“Leaves,” I answered. “The same as last year. Only real.”

We invited our people. We cooked too much. We set out a bowl where anyone could drop a paper leaf with a specific thank-you to someone else at the table. Eva stood to read them before dessert, cheeks flushed, hair escaping its braid, voice steady.

“Thank you, Mr. DeLeon, for teaching me to use the big ladle. Thank you, Aunt Maggie, for the scarf the color of the lake. Thank you, Mom, for pancakes in leaf shapes. Thank you, Ms. Patel, for letting me roll pie dough even when it sticks.”

When the plates were stacked and the dishwasher hummed, I took my phone out and looked, for the first time in months, at the family group chat. It was a quiet museum of old performances. I scrolled to the last photo of that last Thanksgiving—the one where they raised glasses to “well-behaved children.” The dining room glowed. The table was a stage. My parents smiled as if joy had never once had to negotiate to be allowed in.

I didn’t feel the ache I thought I would. I felt distance. A room I had once been trapped in was now just a room other people used to rehearse their best angles. I closed the app and turned off notifications altogether. Not out of anger. Out of health.

Later that night, after Eva fell asleep under a pile of blankets that could double as a fort at a second’s notice, I stepped out onto the balcony with a mug of tea. The air smelled like rain that wasn’t sure it was coming. Lights in other people’s kitchens glowed. A siren wailed two neighborhoods over and then faded into ordinary.

I thought about the girl I used to be—the one who kept auditioning for a role that paid in scraps and criticism. I thought about the woman I am now, who will scrape a batter bowl clean with a spatula and teach a child to press middle C like she means it, who will set boundaries without a speech and enforce them without fire. I thought about the door I closed and the lock I turned.

Here is the part where stories like mine usually say something like, “I threw away the key.” But that’s not quite right. I didn’t throw it away. I put it in a drawer where I keep useful things: extra batteries, a screwdriver, a tiny flashlight. Keys open and close. Boundaries aren’t prisons; they’re gates I decide when to swing. If one day, years from now, two people stand on my porch as different as people can be and ask for a conversation built of apology and practice and proof, I will decide then, with the person I’ll be by that point, whether to unlock anything.

For now, the door is closed.

The next morning, I woke before my alarm. Sunlight pressed a soft square onto the carpet. I made coffee and packed Eva’s lunch and tucked one of her leaf place cards into the pocket of her backpack. She found it at school and later told me she kept it in her desk “for emergencies, and also fun,” which is exactly the definition I would have chosen for proof of love.

That evening, we pulled out the construction paper again. Eva cut leaf after leaf, filling a bowl with color. “Who are these for?” I asked.

“For us,” she said. “For all the days between the holidays.”

We wrote: Thank you for pancakes on Tuesdays. Thank you for people who choose us. Thank you for a house that hums. Thank you for the big ladle. Thank you for second chances we don’t have to take.

When we were done, she taped them to the fridge in a crooked circular wreath, a messy crown of gratitude. We stood back and admired it. It wasn’t pretty the way my mother’s centerpieces were pretty. It was ours.

Our first winter alone arrived with early dark and we answered it with lights clipped to the balcony and late soups and open-door Sundays for whoever needed stew and a chair. We learned that quiet can be a blanket, not a punishment. We learned that some traditions are worth abandoning and some worth inventing.

And on Thanksgiving the next year, when texts started flying in other people’s group chats—their inside jokes and their performances—I didn’t feel excluded. I felt chosen. By myself. By my daughter. By the people around our table who stood not because a ceremony told them to but because a love did.

If you are standing in a kitchen with a phone in your hand, reading words that try to shrink your child, let me tell you what I wish someone had told me sooner: you are allowed to say no. You are allowed to cancel the card. You are allowed to cook pancakes in leaf shapes and call it a feast. You are allowed to build a life that does not require the approval of people who confuse obedience with love.

You can close the door. You can lock it.

And you can live, beautifully, on the other side.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

MY SON ORDERED ME: OBEY HIS WIFE OR LEAVE I SMILED, TOOK MY SUITCASE, AND WALKED AWAY…

MY SON ORDERED ME: OBEY HIS WIFE OR LEAVE I SMILED, TOOK MY SUITCASE, AND WALKED AWAY… Part I…

After Three Years of Silence, I Received a Letter from My Dad. But When I Looked Closer…

After three years of silence, I finally received a letter from my dad. At first, I thought it was the…

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter …

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter … Imagine lying in a…

My Parents Laughed When I Walked Alone To My Wedding, But Their Faces Changed When The Doors Opened

My Parents Laughed When I Walked Alone To My Wedding, But Their Faces Changed When The Doors Opened. My Parents…

On My 30th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.3 Million That I Saved – But They Fell Into My TRAP

On My 30th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.3 Million That I Saved – But They Fell Into My TRAP My…

My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside.” Everyone Smirked. I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, and Left

My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside.” Everyone Smirked. I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, and Left Part I Sunday…

End of content

No more pages to load