Left Alone With Three Children, I Rushed To A Job Interview—But When I Paid The Fare For An Old Man…

Part One

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror that morning and tried to make eye contact with the woman inside it. She didn’t rush to meet me. Fine lines spidered around eyes that had forgotten how to sleep. The grooves beside my mouth had grown deeper, as if every unspoken worry had carved one more millimeter for itself. Gray threads flashed wherever the light dared to be honest.

Thirty-eight, I reminded myself. The mirror, merciless as always, offered forty-five.

A knock rattled the door. “Mom, are you going to be much longer? Sophie has to pee.” Ashley’s voice had found that exact angle where sharp turned to mean.

It was eight already. Forty minutes until we had to be out of the apartment, forty minutes to pull off a minor miracle. I rinsed my mouth, wiped the steam from the mirror, and opened the door. Ashley swept past me with the practiced outrage of a teenager wronged by the existence of walls, tugging six-year-old Sophie along. “Say thank you,” she prompted, as if courtesy were something I owed her.

“Thank you,” Sophie whispered, leaning her forehead into my hip before being dragged inside. I bit down on the sting in my chest and told myself to save the fight for something that mattered. In our life, oxygen was a finite resource; I had learned to budget even that.

At breakfast I set out bowls of oatmeal, glasses of milk, and the last of the banana sliced into four applause-worthy pieces. Ten-year-old Ethan sat without being told, spoon already poised like a promise. Sophie scrambled onto her chair, hair sticking up like a halo that had given up. Ashley stared at the oatmeal as if it had personally insulted her.

“Oatmeal again,” she said. “And the milk is warm.”

“It’s not warm,” I answered, keeping my voice steady. “It’s straight from the fridge.”

She snorted. “Maybe for you it’s cold. Honestly, you don’t know how to make anything decent. You can’t even be bothered with makeup. You look like an old woman. Mrs. Henderson’s in her forties and looks better than you ever did.”

The words sliced with the clean efficiency of someone who’d practiced. I could’ve told her what I’d carried this week alone: the double shift at the hotel, the heater that had started making a sound like it was crying, the call from the mechanic, the fact that the new shoes Sophie needed would mean we ate beans for a week. But I swallowed it down. In our apartment, pride was a luxury and silence a survival technique.

“Stop being mean,” Ethan said, cheeks flushing like he’d stepped into wind. “Mom works hard. At least we have food. You should be grateful.”

“Grateful?” Ashley kicked the table leg. “For this? For living like we’re poor? For riding that junk car to school and pretending it’s normal?”

“I like Mommy’s oatmeal,” Sophie said into her spoon, voice small enough to get lost between sentences.

I counted behind my eyes the way the counselor in the free clinic had taught me once: inhale to five, exhale to five, start again. By the time I reached ten, the urge to pick up the bowl and fling it at the wall had run itself out like a toddler.

“Finish your food,” I said quietly. “We’re leaving in ten.”

We left in twelve because zipper teeth are not known for their kindness. The December cold slapped our cheeks awake the second the apartment door opened. I buckled Sophie into her booster, checked Ethan’s homework inside his backpack by touch because mothers eventually develop echolocation for math worksheets, and slid behind the wheel of the sedan. The engine coughed until I wondered if I should pat the dashboard and apologize for asking it to live again. It finally sighed itself awake. Ashley folded herself into the backseat and looked at the window like it was a TV channel she despised. Ethan pressed his forehead against the cold glass and drew a heart that fogged and disappeared and fogged again.

Two blocks in, Ashley started without looking at me. “Do you ever notice how other moms actually care? Mrs. Parker drops Haley off in an SUV. She wears heels. Makeup. You look like a tired maid. No wonder Dad—”

The rest of the sentence slammed into the windshield and slid down it unsaid. I pulled the car to the shoulder so fast Ethan’s pencil skittered across the floor mat.

“Get out,” I said. My voice shook, but it held.

Ashley’s lips parted. She needed a second to recalibrate. “Fine.” She yanked the handle. The door slammed hard enough to rattle the car’s bones. Sophie flinched, then started to cry. Ethan rounded on the empty air where his sister had been.

I wanted to call Ashley back. I wanted to slingshot my words out the window and lasso her stubborn shoulder. But exhaustion and pride are kissing cousins; they put their hands on your mouth and say, don’t. I merged back into traffic and drove toward two schools and a front desk where a manager tapped her clipboard like a metronome for my failures.

By the time I poured myself behind the hotel’s front desk, Mrs. Cartwright had already clocked me with a look. “Cutting it close again, Linda.”

“I know. I’m—”

“Don’t say traffic.” She pressed her clipboard to her chest like a shield. “Two complaints yesterday. Wrong wake-up call time and not enough smiling. This isn’t a charity.”

No, it wasn’t. If it had been, there would have been bread and kindness.

I smiled with the part of my face that still remembered how and answered phones and typed names and handed out key cards while my brain replayed the image of my daughter walking away from the car like she had just fired me from her life. When my shift ended and Scranton’s early dark had already settled its coat across the streets, I drove home to a quiet apartment and a kitchen table where Ethan sat pretending to work fractions while he watched me the way you watch a glass perched too close to the edge. Sophie curled on the couch with her thumb and blanket and The Very Hungry Caterpillar like liturgy.

“Ashley?” I asked.

He shook his head. I called and called. Voicemail collected my apologies like stamps. At eleven, I found the bathroom—our apartment’s only room that allowed a door—to be the right place for falling apart. A text pinged while I was sitting on the cold edge of the tub: I’m not coming back tonight. I don’t want to live with you anymore. Stop calling me.

“Mom?” Ethan’s little voice came through the door like a hand. “Are you crying?”

I wiped my face with the heel of my palm and tried to pull my mouth into something that could pass for a smile. He hugged me anyway, his thin arms fierce as any promise. “We’ll be okay,” he said, and I decided to believe him because he was the only person in the room who had ever been right about anything without trying.

The morning dragged me out of bed by the ankles. I coaxed Sophie into tights while she slept sitting up. Ethan brushed his teeth without being asked because he had been old since he was eight. Ashley’s room remained a demonstration of absence. At school, Mrs. Graham, the guidance counselor with the voice like concerned tea, told me Ashley hadn’t been in class for three days. “Truancy requires district notification,” she said gently. “Please find her, Ms. Thompson.”

Please find her—as if I had taken off my glasses and mislaid her on a dresser. I called every friend’s number listed in the school directory, the ones scribbled on scraps of paper, the one I had sworn I would never dial again. “She’s with a friend,” one girl whispered and hung up. That night, when the text finally came—I don’t need you—I pressed the phone to the counter and thought of all the ways in which that sentence was biologically inaccurate.

Somewhere between calls to voicemail and pretending leftover spaghetti was a party, my life did the thing it liked to do: it overlapped a new crisis on top of the previous one. The car died, this time like it meant it. A mechanic I barely knew looked under the hood the way a doctor looks at a chart when he’s about to ask if you have family nearby. “Transmission. Fifteen hundred at least.”

Fifteen hundred might as well have been fifteen thousand. I found the coffee can behind the cleaning supplies and shook out the emergency money. Every day of our life qualified as an emergency; we had simply agreed not to use the word all the time. By nightfall, my savings looked like someone had cut the bottom out of a cloud and watched the weather pour through.

In the morning I went to Martha’s—Mark’s mother—because the universe has a dark sense of humor. Her house smelled like antiseptic that has given up and old fabric that has not. She lay in the rented hospital bed in the den, the TV volume up loud enough for people in other houses to hear histrionics from shows where the pictures are too bright.

“You’re late,” she said. The stroke had moved half the words down a slippery slope, but this one still climbed.

“I’m here now.” I adjusted her blanket, peeled her an orange with thumbs that had learned that gentleness doesn’t always get you gentleness back.

“What do you think?” she asked when I asked how she felt, and I could have laughed if laughing didn’t use calories we needed for rent.

He was his father’s son, she told me when I washed her hair. Restless. Never satisfied. She meant Mark. She meant my marriage that had died twice—once in a car wrapped around someone else’s life and once in a police report. I nodded because this was not the house where my opinions mattered.

Everything, I thought on the drive home, was a balance beam with no mat beneath it.

Ashley came back on a Thursday like she’d run to the corner store and decided to make it next week instead. She shouldered the door open and threw her backpack down like an accusation. “I needed a break,” she said. “You were suffocating me.”

Sophie squealed “Ash-ee!” and attached herself to her sister’s legs. Ethan, wise as a monk, looked at the tabletop and waited.

“Dinner’s almost ready,” I said because I did not trust my throat with anything else.

“I’ll do it,” Ashley muttered, elbowing me aside and producing chopped vegetables in clumsy handfuls. The chicken burned on one side and the carrots were daringly crunchy, but we ate it like it was the first course at a wedding where the bride had made it down the aisle without tripping. After, Ashley sat back, arms crossed, eyes half-closed. “Don’t get used to it,” she said. “I’m not trying to be perfect. I just didn’t feel like eating garbage tonight.”

It wasn’t an apology. It was an opening, thin as a paper cut. I took it.

The interview was on a day the sky pressed down so low it felt personal. A storm had marched in from the west and started shouldering cars into ditches. I should have canceled, but the paper in my pocket promised a wage high enough to turn beans into chicken at least twice a week. I layered myself into my oldest coat and two sweaters that believed in each other and headed downtown.

By the time I reached Center Street, wind had teeth. Snow didn’t fall so much as attack from the side. Somewhere between the bus stop and the restaurant, an old man materialized from the white, coat too thin for anyone who had a choice. He dragged a small suitcase that kept trying to sit down in the slush.

“Sir!” I shouted over air that made the inside of my nose hurt. “Do you need help?”

“Train station!” he shouted back. “Gotta get to the station.”

The station was three miles and seven blisters away. I flailed an arm at the single cab crawling down the street with its hazard lights like eyelids. The driver rolled down his window and told me his meter worked and the world didn’t. The old man patted empty pockets with hands that shook.

Without thinking, I peeled my glove off and pulled crumpled bills I had saved for nothing specific and everything. “I’ll cover it,” I said to the driver and to myself and to the part of me that always saved the last bite for someone else.

“You don’t have to,” the old man said, shock and pride doing their dance.

“I know,” I said. “Get warm.”

He scribbled an address on a torn corner of a pharmacy bag. “At least take this,” he said. “Come by sometime. I’ll repay you.”

I shoved the paper into my coat as the cab door closed and his breath fogged the window. Then the car was gone, the white closed around me again, and I was a woman in a snowstorm who was late to an interview that mattered more than breakfast, with cheeks on fire and hair wet against skin that had already decided not to forgive me for any of this.

I missed the interview. I missed it in the precise way people who don’t have a safety net miss things: with every part of me trying, with no part of me enough against weather and life. I trudged home and found Ethan at the table with his pencil and math like a holy man with his texts, and Sophie asleep in the crease of the couch with jelly on her cheek, and Ashley in her room pretending she didn’t wish she’d asked where I was going. I sat by the window and told myself I hadn’t failed; I had just chosen a different job for thirty seconds. It wasn’t a paycheck, but when I replayed the old man’s grateful mouth in the cab, something unclenched in my chest.

Sometimes all that keeps a person soft is the knowledge that they can still choose to be.

Part Two

Three days passed before someone knocked at our door at an hour that wasn’t for deliveries or trouble. I wiped my hands on a dish towel and opened it.

It was him—the old man—without the suitcase that had looked like it needed a wheelchair. His coat was heavier, his eyes clearer. Beside him stood a man who pulled seventeen years out of my lungs as if time were a magician and I the audience since childhood.

“Linda,” he said. His voice had been sanded by life but it still found the note that used to make my chest loosen. “It’s me.”

“Daniel.” Saying his name felt like stepping onto a floor I hadn’t realized was there.

Ashley peered around the hallway corner just then, drawn by the gravity of an adult saying my name like a present. Her eyes pinged from his face to mine and back, and I saw the exact second she recognized herself in a stranger’s jawline.

“Mom,” she said. “Who is this?”

I held onto the doorframe because my knees had more truth in them than the rest of me. There had been a thousand versions of this moment in my head. None of them involved a Saturday afternoon or spaghetti sauce on the stove.

“This is Daniel Hayes,” I said. My voice broke on the second word. “Your father.”

Time didn’t stop, but it did rearrange its furniture.

“What?” Ashley’s face paled, then hardened. “No. Dad was—Dad was Mark. He—” She shook her head like a dog after a bath. “You’re lying.”

Behind me, the spaghetti threatened to become allegory. I turned the stove off and sat because staying upright felt like arrogance.

I told her. I told both of them. Not everything at once—you can’t take out a lifetime and lay it on a table like laundry and expect people to know which piece belongs to whom. But I told her the parts I had protected her from and the parts I had used to protect myself. I told her about being eighteen and in love with someone whose mother looked at me and saw a list of things money cannot buy and resented me for every one of them. I told her about the threats—soft at first, then louder—if I didn’t step aside, if I didn’t make myself a footnote in a story they had already written. I told her I found out I was pregnant after I had become a footnote and that by the time I tried to write myself back into the book, someone had stolen the pen.

Daniel stood the whole time, his hands opening and closing like he was practicing dropping something heavy. “She told me you’d left,” he said when I finished, his gaze on the space between my shoes. “My mother. She said you’d found someone else. She said you didn’t love me. I believed her because I wanted to believe her. I didn’t know how to fight who she was. I should’ve learned.”

Ashley’s chin wobbled. She was still trying not to let her mouth do that thing that made her look younger than she wanted to be. “So all this time,” she said, “you let me call a liar ‘Dad,’ and the real one was…what? Waiting around until a blizzard blew him here?”

“I wasn’t waiting,” Daniel said softly. “I was ignorant. There’s a difference, but it doesn’t change what you lost. If I had known you existed, nothing would’ve kept me away. Nothing.”

Ashley flinched like he’d thrown her a rope and she’d been too proud to catch it. She turned away and wiped at her eyes with her wrist the way she had when she was five and still let me do it for her. “I don’t know if I can forgive either of you,” she whispered. “But I’m tired of being angry all the time.”

She sat down.

The old man—Daniel’s father, I understood now by the shape of his hands and the ready apology in his posture—cleared his throat. He set a folded paper on the table with the kind of care you give to something that could break or save. “My name is Victor Hayes,” he said. “I’m the man you paid a fare for.”

“I didn’t pay it for you,” I said before I could stop myself. “I paid it because it was what the day asked me to do.”

He nodded like I had passed a test I didn’t know I’d been taking. “This may feel…complicated. It shouldn’t be. I asked the driver where he had picked me up, and he told me about a woman outside Lee’s Diner in a blizzard who waved him down with a hand that looked like it’d frozen if kindness hadn’t kept it warm. I wrote my address on a scrap and asked you to come by so I could repay you. When I got home, I recognized your name from a story I’d spent years trying to rewrite.”

He slid the paper closer: a rescheduled interview time for Lee’s Diner—handwritten, signed by Mae Lee, the owner, with a note: Heard you were the woman who got Victor to the station. Come in Monday. I don’t hire résumés. I hire people who make the world less cruel.

I blinked down tears I had promised myself would be rationed. “I missed my interview,” I said. “The storm—”

“I know,” Victor said. He reached for the sugar bowl like he didn’t want to watch my face in case I dropped gratitude on it. “But I told Mae what you’d done. Her parents crossed the ocean with nothing in their pockets but hope and instructions to be brave and kind. She keeps a booth for both.”

“This isn’t charity,” Daniel added quickly, like he’d been waiting to say it. “You still have to cook circles around boys who think they invented eggs. But Victor told me about you, and I remembered what it felt like when your name was the only thing in my head.”

“We’re not here to buy anything,” Victor said. “We’re here to repay what was owed for a long time. Not money. Truth.”

Truth, I have learned, is not a polite guest. It sits in the chair you were saving for denial and then asks you to pass the salt. But we fed it because starving it hadn’t gone well for any of us.

Over the next weeks, Daniel showed up without fanfare. He didn’t knock with gifts or promises he couldn’t keep. He brought groceries sometimes and asked me before he took the trash out, as if he knew that in our house, competence was a thin wall I didn’t want anyone leaning too hard on. He took Ethan to the park and didn’t try to teach him to be a man in an afternoon. He sat with Sophie while she drew cats that looked like jellybeans. He learned, quickly, that the only way to make Ashley speak was to stop expecting it. He told her he was there and then sat there.

Ashley bristled like a porcupine that had gotten used to sleeping on its own quills. She lobbed sharp things at him when he least expected it. Where were you at my sixth-grade recital? Would you have taught me to drive? Do you snore? He didn’t answer all of them. He answered the ones that mattered with sentences that were not excuses. I didn’t know. Yes. Only when I’m sick. The rest he let hang in the air until they fell to the floor and stopped being weapons.

I went to Lee’s Diner on Monday with a comb through my hair and a shirt so clean it felt new. Mae Lee looked me up and down like a surgeon deciding if a heart could take a new rhythm. “Victor says you paid his fare,” she said. “I say that and a dollar will get you coffee. I hire grit and grace. Show me both.”

She slid a ticket onto the pass and barked orders while the griddle hissed. I didn’t flinch. My hands remembered onions and heat and the weight of a spatula. When she said behind and walked past me, I moved like I’d been born in a kitchen. When the bell dinged, I plated like something small depended on the edges being clean.

“You start Friday,” she said after an hour. “Don’t be late and don’t make me regret it. We’re a family in here, and that means we yell and forgive.”

Victor came in later and ordered coffee like it was a miracle he could pay for. He looked smaller sitting at the counter than he had in my doorway, but his eyes were brighter. “I owed you a fare,” he said. “Turns out I owed you a father too.”

I shook my head. “You don’t owe me that. You owe your son. And he owes himself.”

He nodded. “Then we’ll call it even when both of you feel it in your bones.”

The first paycheck from Lee’s felt like relief edged with responsibility. I used it to keep the lights on and the internet paid because Ethan’s math teacher insisted homework appeared on a screen now. I put twenty in a jar on the fridge for “fun” and watched the kids stare at it like it was a zoo exhibit. We spent it on Friday ice cream in January because the cold doesn’t care if you add to it.

Ashley’s truancy case got a second chance when Mrs. Graham realized anger was not the same as defiance and that kids sometimes needed time to unravel the knot grown-ups had tied. Ashley went back to class with a hoodie and a look that dared anyone to say glad you’re back in a tone she wouldn’t like. She failed a test and then passed the next. She slammed her door and then opened it and asked, without eye contact, if I wanted to watch a show with her. We sat with our ankles touching like we were remembering something we had never actually lived.

Martha still needed bathing. Her bitterness didn’t evaporate because my life had decided to be magnanimous for a week. But the work felt different when it wasn’t the only thing the world asked of me. One afternoon, she watched me peel an apple and said, “He loved apples,” as if this were an apology disguised as fruit. “Mark,” she added when I didn’t say anything. “He ate them to the core.” It wasn’t forgiveness, but it was how she knew how to lower her sword for a second.

Daniel’s mother—whose disapproval had once been strong enough to warp the course of two lives—called Victor when she realized I existed again in a way she couldn’t control. He didn’t answer. He was busy helping his son build a bridge with a teenager who had carry-on luggage full of reasons not to meet him halfway. When she finally sent a letter to my apartment, I slid it, unopened, into a drawer with a sickle of understanding: not every truth needs to be invited in. Some can wait outside in the cold until they are ready to knock like a person and not a storm.

The car still coughed, but it coughed less with shifts at the diner lined up behind the front desk schedule. The heater rattled, but Mae’s tips paid a man named Julio who stopped it from sounding like it was going to walk down the hallway one night and move to Florida. Ethan’s face brightened when his math grade did. Sophie lost a tooth and insisted on guessing what the tooth fairy looked like. “Someone tired,” I said, and we laughed until she snored on the couch as if to prove me right.

On a Sunday in late February, the five of us—six if you count Victor, who had the stubborn charm of a man who knows where the spare key is—sat around our table with pizza we hadn’t cooked and salad that proved to the children we were not animals. Ashley folded a slice in half the way her not-father had taught her and chewed with exaggerated care.

“I told Mrs. Parker you got a job,” she said into her food.

“Oh?” I tried for casual and landed somewhere around breathless.

“She said maybe she’d hire you for weekends. She needs help with the bakery. I said you already have a job, like, two, and she said some people need more than one because the world is not a fair distribution of anything.”

I looked at my daughter, who had started the year thinking I was an embarrassment and ended it quoting the woman whose SUV she had used to measure me against. I set my hand down on the table. She placed hers on top of it without looking at me. If I had invented a gospel, it would have been that move.

Later, when the dishes were stacked and the house had fallen into the kind of silence that is not the absence of noise but the presence of peace, I stood at the window and watched the streetlights spray their cones of light onto slush. Daniel joined me, hands in his pockets because he still didn’t know what to do with them around me.

“You did this,” he said.

“No,” I said. “We’re all doing it. Even Ashley. Maybe especially Ashley.”

He nodded. “I don’t expect—” He stopped. “Anything. I don’t expect anything except the chance to keep showing up.”

“That’s the only thing worth expecting,” I said. “And don’t show up with lawn chairs. Bridges still have to be built.”

He smiled, and it didn’t hurt like it used to to see it. It hurt in a different way—the good sore of muscles that have stretched farther than they thought they could.

On the day Lee’s Diner gave me a name tag that meant more to me than anything I had worn in years, Mae pinned it crooked and said, “Grit and grace. Don’t lose either.”

We didn’t. Not when Ashley clamped her mouth shut for a week because her teacher said the word parent and meant father. Not when Ethan scraped his knee and cried more because he thought he wasn’t supposed to cry than because it hurt. Not when Sophie announced she wanted to be a dentist and we all pretended we hadn’t thought that meant she would be more comfortable around pain than the rest of us.

Victor still rode cabs sometimes, despite my insistence that he at least wear a hat that covers his ears. He tipped like a contrite millionaire and made a point of asking drivers about their families. “Repayment,” he told me once when I scolded him for not taking the bus. “Not for the fare. For a woman in a storm who chose to be the kind of person I want my son to be.”

He said it in front of Ashley on purpose. She rolled her eyes because she was constitutionally required to. But later that night, she put a dollar in the jar on the fridge labeled FUN and another labeled GAS and then wrote under FUN in small letters: and kindness. She pretended she hadn’t.

On a morning in March that smelled like wet concrete and first chances, I stood in front of the mirror again. The gray was still there. The lines were deeper. But the woman in it looked back at me sooner this time, and she didn’t look like a wound. She looked like a person who had survived without choosing to become sharp, like someone who had decided that tired and kind were not mutually exclusive.

I tucked a strand of hair behind my ear, kissed my fingers, touched the glass so the gesture could count twice, and went to wake the kids. Sophie leaped into my arms. Ethan made a joke that made coffee come out my nose. Ashley bumped my shoulder in the hallway like a truce and said, “Your cooking’s not that bad.”

We drove to school with the car coughing a little and the windows fogging until I cracked one and told everyone to pull their sleeves down because the cold owes us nothing. When I dropped them off, Ashley didn’t slam the door. She didn’t say goodbye either. She lifted a hand without turning around.

At the diner, I flipped eggs and listened to orders shouted like advice. At lunch, Victor came in and sat at the counter and told me a story about the time he tried to fix a leaky sink and ended up calling three plumbers and a priest. I laughed harder than people in aprons are usually allowed to. Before he left, he pressed a folded bill into the tip jar and said, “For the fare,” like we were actors in a play that ends the same way every time because the audience wants to clap there.

When I got home that night, there was a note on the table in Ashley’s handwriting. I told Mrs. Parker I could watch the bakery Saturday so you can sleep. Don’t make a big deal out of it. The note was taped under the jar labeled FUN. There was a five inside.

Sometimes endings don’t announce themselves. They arrive quietly, set their suitcase down in the hallway, and show you instead a beginning.

I still measure months by bills and school calendars and what the car sounds like in the morning. There are still nights the quiet feels like a warning. But when I close my eyes now, I don’t see a hallway with a door I can’t open. I see a cab in a blizzard pulling away and a woman with numb fingers choosing warmth for someone else. I see an old man at my door with his son beside him and the way my daughter’s face looked when she realized she had a father who wasn’t a lie.

Sometimes all that changes a life is the moment you refuse to keep walking past someone else’s storm. Sometimes you throw your last dollars at a cab and end up with a job, the truth, and the permission to build a different kind of family around a kitchen table sticky with spaghetti sauce.

We’re not rich. We’re not done. But at the end of the longest days, I sit on the couch with a kid tucked under each arm and another pretending she only wanted to watch a show because the light in the room is better here, and I think: this is enough. Not as compromise. As conclusion.

I once stood in front of a mirror and didn’t recognize myself. Now, when I catch my reflection in the diner’s window as I pass with two plates balanced on one arm, I do. She’s the woman who paid a fare she couldn’t afford and got change she never expected. She’s the mother who told the truth and didn’t let it ruin everything. She’s the person who learned that being left alone with three children is not the end of a sentence; it’s the beginning of a story you get to finish.

And when I write it down, I make sure to include this: we chose to be kind. And the world, eventually, chose to be kind back.

END!

News

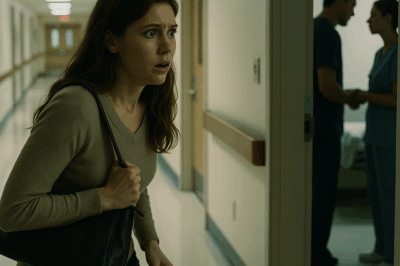

I Rushed to the Hospital to See My Mother—But Ended Up Overhearing My Husband Talking to a Nurse…CH2

I Rushed to the Hospital to See My Mother—But Ended Up Overhearing My Husband Talking to a Nurse… Part…

On My Wedding Day, I Thought I Gained A New Life—But I Inherited My Mother-In-Law’s Tragedy Instead… CH2

On My Wedding Day, I Thought I Gained A New Life—But I Inherited My Mother-In-Law’s Tragedy Instead… Part One…

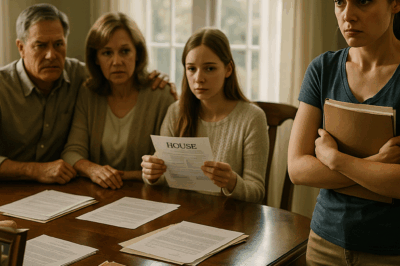

At The Reading Of The Will, My Husband Could Barely Hide His Smile. But The Moment He Heard… CH2

At The Reading Of The Will, My Husband Could Barely Hide His Smile. But The Moment He Heard… Part…

My Parents Gave Everything to My “Fragile” Sister After Siding With My Ex. ch2

My Parents Gave Everything to My “Fragile” Sister After Siding With My Ex Part One The smell of old…

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt. ch2

They Begged Me to Pay for Surgery—Then I Found the Sports Car Receipt Part One The call came at…

My Mother Dumped Me Like Trash at 12, Now Crawls Back: ‘Honey, Let’s Discuss the Inheritance!’ ch2

My Mother Dumped Me Like Trash at 12, Now Crawls Back: “Honey, Let’s Discuss the Inheritance!” Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load