In the Middle of the Celebration, I Wanted to Surprise My Husband—But What I Found in His Office…

Part 1

I held the test in my hand and stared at the two pink lines like they were a secret scrawled in a private language—one only my body and I could read. After three long years of trying, of bargaining with calendars, of stacking hope against disappointment until the weight of it bent my spine, it had finally happened. I was pregnant.

I pressed the little plastic stick to my chest and let out a breath that trembled on the way out. Somewhere as small as a pearl and as loud as a cathedral bell, a life had started. Ours. Mine. A sentence I’d been trying to write for so long I’d forgotten how good it felt to find the right word.

October sunlight spilled through the kitchen windows, warm and golden, lighting up the table I’d spent all morning dressing for celebration—Eleanor’s 60th. Napkins folded like little sails, silverware lined with the precision of an apology, roast pork resting beneath a tent of foil, garlic potatoes perfuming the air like a memory I could almost name. I adjusted a fork that didn’t need adjusting, fluffed napins that had already been fluffed. My hands needed a job if they weren’t going to give me away.

Today was Eleanor’s day. But folded in the lining of it, humming just beneath the surface, was my own eruption of joy. I could already see the moment: Ethan’s hands on my face, eyes bright, that startled laugh of his that felt like a door thrown open. He would kiss my forehead, my mouth, then—ridiculous and perfect—bend to kiss my belly, whispering something like, “We need to buy a crib today.” We would argue lightly about names, about painting the guest room, about middle initials that linked us like stitches.

“Babe, you in here?” he called, the shape of his voice sliding down the hall before he did.

“In the kitchen,” I said, smoothing a nonexistent wrinkle from the tablecloth and tucking the test into my back pocket, as if it could keep from blazing through fabric.

Ethan stepped into the room with that infuriating, effortless charm that had hooked me the first time I saw him. The ocean-blue shirt he’d chosen made his hazel eyes tip toward gold. He kissed my cheek, surveyed the table, gave a low appreciative whistle. “My mom’s going to love this.”

“She deserves it,” I said. “Sixty’s a big deal.”

“Not as big as whatever you’re keeping from me,” he murmured at my ear, the tease bright and easy.

“Later,” I said, fighting a grin that wanted, recklessly, to be the whole story. “When it’s just us.”

“You’re killing me, Anna.”

The doorbell rang, cheerful and oblivious, and the moment skittered away under the feet of arriving guests.

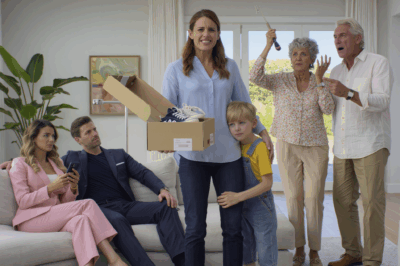

The Mitchells swept in as if they were arriving at a gala rather than our front door. Eleanor moved like a woman who had never not been watched: silver hair pinned with surgical exactness, navy suit sharp enough to correct your posture just by existing. “Anna, sweetheart,” she said, kissing my cheek, eyes softening by one degree. “Everything is perfect.”

“Thank you,” I said, offering her a glass of wine. “I hope it’s to your liking.”

“It’s lovely,” she said, which—coming from Eleanor—was confetti and fireworks.

Frank handed me lilies and a bottle of scotch without a word. It was his dialect of affection.

Neighbors arrived, then teachers Eleanor had once mentored, then Angela and her husband, Mark, their two kids running laps around the entryway like they’d trained for it. The house filled with voices and perfume and the soft public laughter people bring to one another’s living rooms. Compliments ricocheted off the crown molding.

“Anna, how do you do it?”

“You’re amazing.”

“This looks catered.”

I smiled like I knew how to wear it. I refilled glasses, eased plates into hands, slid serving spoons into bowls. Every time my hand crossed my waist, my palm found my stomach in an unconscious benediction. You’re here, I told the little life, over and over. You’re already loved.

Ethan did the thing Ethan did in rooms—commanded them without looking like he was. He told a story about a work trip gone wrong—something about a hotel mix-up and a man in boxers yelling at a receptionist. The room tipped with laughter, even Eleanor’s mouth losing its line for a second. I stood in the kitchen doorway, dishtowel in my hands, and let myself watch him with simple, uncomplicated pride. He looked so alive and so sure, and I had the audacity to think: mine.

I wanted to stop time right there, before the part where everything I knew about my life rearranged itself into a picture that didn’t include me.

Dessert moved the party into a looser orbit. I was arranging coffee cups when Eleanor said, lightly, “Where’s Ethan? Haven’t seen him in a bit.”

“He was just here,” I said, though suddenly my memory had less footage than I wanted. “Probably stepped out to take a call.”

“Check his study,” Angela said, juggling plates the way only mothers do. “He still keeps work stuff in there, right?”

I walked the hall that had always felt familiar and, for the first time, felt foreign. The door to his office was half-closed, lamplight stitching a slender seam across the floorboards. I reached to knock.

His voice slid through the gap—low, intimate, and not the voice he used with me.

“I know. I know. I hate it too,” he whispered. A soft chuckle—tender in a way that made my skin go cold. “But what do you want me to do? The house is full of people.”

My hand hovered above the knob. I didn’t breathe. The hallway air grew thick, as if it had weight.

“I can’t just walk out. It’s her mother’s birthday. Even for me, that would look bad.”

A pause. Then a laugh I didn’t recognize.

“No, of course she doesn’t know. Anna believes everything I say. Like clockwork.”

The first breath I took after that hurt in my ribs.

“I’ll tell her soon. A few more weeks. Let the party dust settle. Then I’ll say we’re not working anymore. It’s no one’s fault. We drifted. You know—the usual soft-landing garbage.”

I stepped back because the floor felt like water. I pressed my hand flat to my sternum like I could keep my heart from walking out without me.

“I mean, come on. She still thinks we’re going to have a baby.” He laughed. “Poor thing’s probably planning names.”

The warmth in my belly curdled into a cold I will always remember.

“She’s sweet,” he added, like he was ordering coffee. “But she’s not you. She’s soft. Predictable. She’ll cry, maybe beg, but she’ll let go eventually.”

I didn’t hear the rest. I didn’t want to know if there were more graces he planned to grant me. I walked away on legs that didn’t feel attached to me, made it to our bedroom, and let the tears come without the dignity of sound. I held the top of the dresser and gasped like someone learning how to breathe.

In my pocket, the test pressed into my hip like a brand. I took it out. The two lines stared back—accusation and promise twinned. How do you tell a man who is already writing his exit that you are carrying a door he will not be allowed to close?

I washed my face and played at composure. When I slipped back into the living room, Ethan had reappeared—perfect host, impeccable timing, a man with a mouth full of cake and a story about a faulty smoke alarm. He brushed my arm and murmured, “You good?”

I nodded. “Just tired.” The lie slid like a well-practiced prayer off my tongue.

When the last guest left and the house exhaled, he kicked off his shoes and flopped onto the couch, humming under his breath like a man who had gotten everything he wanted and then some. “Come on,” he said. “Sit. You’ve been running around all day.”

I sat because my legs didn’t know what else to do.

“So?” he said, bumping my knee with his. “What’s the big news?”

I looked at his face—the one I’d loved in every light—and saw a stranger wearing a mask my heart had carved. My hand went to my pocket, then stopped. I had tucked the test under the sink before dessert, as if hiding it could stop time from reading it aloud.

“Tomorrow,” I said. “I’m wiped.”

He looked disappointed for the length of a blink, then shrugged and stretched. “Okay. Suspense, then.”

I watched him walk down the hallway humming the same tune he had once hummed while painting the guest room. The door clicked shut. The house looked like a celebration had happened to it. It felt like a wake.

I didn’t sleep. Patterns unspooled behind my eyes: late nights big with no details, business trips that had stretched like gum until they snapped, a new cologne smell I had accepted as the cost of a department store sample lady doing her job too well. The shirt I washed with a lipstick smear he’d attributed to Angela’s too-enthusiastic hug. The way his phone had become an extra limb.

Grief is a forensic scientist if you let it be.

By morning, the only thing I knew how to do was clean. I scoured counters that didn’t need scouring, arranged spice jars alphabetically as if cumin and coriander could put my heart in order. Ethan went for his run—sweats, earbuds—a man whose life had not detonated twelve hours earlier because he had placed the explosives and left the building first.

The second the front door closed, I picked up his phone and unlocked it. Our wedding anniversary. I let the irony touch me and leave.

The messages were there like an answer key. No name, just a number, but the thread did all the work.

I missed you all night.

I hate pretending.

When can we be done with this?

She won’t see it coming.

Photos. An overpriced restaurant I didn’t recognize. A woman—Madison—standing in a red dress that Rachel had described in passing weeks ago when she’d mentioned seeing someone who looked like Ethan at the mall. A picture on our back porch, my windchimes winking in the background as if they wanted to be anywhere else.

I got to the bathroom before the nausea won. It wasn’t morning sickness. It was clarity in the body’s only language: expel what is poisoning you.

I didn’t want to call Rachel. I didn’t want to say the words out loud and let them harden into the air. I also didn’t want to be alone in a room with the truth when it was this large. Can we meet today? I texted. It’s important.

Of course, she replied. Same place.

At the café, the espresso machine hissed and plates clinked and everyone went on living because that’s what people do while your life is becoming a new shape two tables over. Rachel slid into the booth, eyes widening as soon as she saw mine.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

I shook my head and told her everything. The office door. The sliver of light. The voice he saved for someone else. The messages. The photos. The pregnancy test like a lighthouse and a siren.

When I finished, she whispered, with the kind of reverence rage teaches you, “That son of a—” and I laughed a sound that hurt where laughing lives.

“I saw him,” she said carefully, after the quiet made room for more. “At the mall. A few weeks ago. With a blonde. I didn’t tell you because I didn’t trust myself not to be wrong. They were looking at rings.”

“Jewelry,” I said, mouth numb.

“She tried one on,” Rachel said. “He kissed her temple.”

“He’s buying her a ring,” I said, the sentence assembling itself without my permission. “He plans to propose after he divorces me.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, and meant it like a hand braced on your back so you can stand.

“It’s not your fault,” I said, because it wasn’t. To trust your husband is not a flaw; to choose the wrong man is not a moral failing. It is a lesson, and I was learning it with my whole life.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“I’m going to see a lawyer,” I said. The words felt like putting my feet on a floor I had forgotten could hold me.

“And the baby?”

“I’m keeping it.”

“You won’t be alone,” she said, and reached across the table and laced her fingers through mine the way you do on slick sidewalks.

I spent the afternoon setting a table I had no interest in eating at. Steak with garlic butter. Mashed potatoes with rosemary. Caesar salad shaved with too-much Parmesan because grief makes you generous with some things and stingy with others. Candles lit. The dress he had once said I was beautiful in. The theater of it steadied me.

The door opened at six. “Smells amazing,” he said, and kissed my cheek. “What’s the occasion?”

“Us,” I said lightly. “A date.”

We ate in a silence he found comfortable. He told a story about an incompetent client and a coworker who never replied to emails. He asked me if I was okay when he remembered to. I said I was tired. He said, “Same,” and moved on.

After dessert, I stopped his hand on the wineglass. “We need to talk.”

He froze for a fraction. Set the glass down. “About what?”

“About us.”

“Okay,” he said, the word more syllable than promise.

I walked around the table and sat beside him because I wanted to see what his eyes did when the mask slipped. “I know,” I said.

He blinked. “Know what?”

“About Madison.” I didn’t drag it out. “I heard you on your call during the party. I saw the messages. The photos. You can stop pretending.”

“How long have you known?” he asked after a beat, voice paper-thin.

“Since your mother’s cake,” I said. “Happy birthday.”

He exhaled a sound that wanted to be regret and didn’t have the range. “I didn’t want it to happen like this.”

“But you did want it to happen.”

He met my eyes and chose a simple truth. “Yes.”

“Do you love her?”

A nod that took his chin with it.

“And me?” I asked, because the part of me that had set tables for years needed to stack this answer in the right place. “Did you ever?”

“I did,” he said. “I still care about you. I just—”

“Not enough,” I finished for both of us.

“I was going to tell you,” he said. “I didn’t want to hurt you.”

“You already did.”

“There’s more,” I added, because the table had another dish to serve. “I’m pregnant.”

His head snapped like a rubber band. “What?”

“I found out the morning of the party. I was going to tell you before I found out who you were.”

He stood, paced a small strip of rug threadbare. “You’re serious.”

“I am.”

“This—” He dragged a hand through his hair. “This changes everything.”

“No,” I said, and was surprised by how true it tasted. “It doesn’t.”

He stopped. “Anna—”

“I’m keeping the baby,” I said. “And I’m filing for divorce tomorrow.”

He sat like someone had turned gravity up on his chair. He looked like a man inventorying consequences. I looked like a woman who had run out of permission slips to sign.

He packed that night. Not everything. Enough to leave with a story where he could still be the protagonist if he told it right. I stood at the door and watched a future I had set a place for lift his suitcase and walk out, humming a tune I no longer recognized.

The silence he left behind was loud and honest. I liked it for that.

At eight a.m., I sat in a leather chair across from a lawyer whose office smelled like paper and quiet power. I told him about the affair and the photos and the pregnancy and the woman in red. “You’re in a strong position,” he said. “You have proof. You have a child on the way. We can do this without burning the building down.”

At the clinic, they told me six weeks. They handed me prenatal vitamins and a stapled packet called Your First Trimester. I held it like a passport and a map. At work, I sat across from my boss, Linda, and said the words I didn’t rehearse and didn’t need to: “I’m getting divorced. I’m pregnant. I’m going to keep working.”

“You’re one of the most reliable people here,” she said, and those words saved me from crying in public. “We’ll figure it out.”

At home, I walked the rooms like a new tenant. His shoes were gone from the mat. His cologne had stopped haunting the hall. The guest room—our once-nursery—had shaggy carpet and an old rocking chair I’d rescued from a yard sale two summers ago. I ran my fingers along the windowsill and pictured late nights that were also early mornings and a name I hadn’t chosen yet.

I called my parents. My mother cried the kind of tears that don’t need sound. My father’s mouth thinned with anger he had no place to put. “I’m pregnant,” I said at the end of a long explanation. The air changed.

“You’re going to be a mother,” my mother whispered. “We’re with you.”

For now, that was enough to sleep a little.

Three weeks after he left, I took down the photo in the hallway—Big Sur, wind in our hair, eyes full of a future that never came. I wrapped it in newspaper and wrote old life on the box with a black marker. I didn’t throw it away. I didn’t need to keep it where people could see.

Rachel came with garbage bags and a soundtrack. “Want to burn this?” she joked, holding up his college sweatshirt.

“Tempting,” I said, and laughed in a way that made my ribs ache less. “Goodwill.”

When we were done, the house was lighter by a few boxes and a few ghosts. I lit a candle and ate soup on the couch and read a chapter of a baby book that started with the sentence You are stronger than you think. For once, I didn’t argue.

He texted once: Can we talk? I miss you. I didn’t reply. He showed up in the rain, hair plastered to his forehead, looking like a man who wanted to feel absolved. “I just want to talk,” he said.

“No,” I said. “You want to feel better.” He said it was a mistake. I said it was a choice. He looked past me as if the past could wave from the hall. I closed the door gently and then sat down and folded laundry and put on soft music because the best revenge is evidence of growth.

On Sunday, I went to a parenting class at the community center and sat in the back. “First time?” a woman named April asked. “Me too. My ex ran off with his yoga instructor.” We laughed. There is something holy about laughing with strangers at the absurdity of your own survival.

I drove home under a quiet sun and realized I wasn’t just surviving. I was standing. Soon enough, I’d be ready to run.

Part 2

The first time she cried, everything else went quiet. White walls and sterile light and the shoed whisper of nurses receded. The world shrank to a sound that split me open and stitched me together in the same breath. They placed her on my chest: warm, damp, furious with life.

“Hi,” I whispered. “It’s just us.”

I named her Clara Grace. Clara because clarity is a gift people don’t talk about enough. Grace because I had learned to handle myself gently, finally, and I wanted her to be anchored to that lesson whether she needed it or not.

The nurses said I was calm. I didn’t tell them I had done the hardest work in a kitchen months ago listening to a voicemail and choosing a future.

Rachel came with flowers and a stuffed fox and soup that tasted like home. “You did it,” she said, eyes shining.

“We did,” I told her, because survival is a team sport no one gets a medal for.

My parents arrived and cried the good kind of tears. My mother kissed my forehead and apologized for every time she hadn’t noticed my quiet had turned into a bruise. My father held Clara like a prayer he could finally say out loud.

A letter arrived later—from Ethan, no return address. I don’t deserve to be a father, but if you ever want her to know me, I’ll wait. I read it twice, then slid it into the sleeve at the back of Clara’s baby book. Not as a promise. As a record.

We moved back home in winter. I painted the nursery yellow—sunflower, not butter—and hung prints of clouds because baby rooms should be full of things that teach your eyes to look up. Above her crib, I framed three sentences: You are loved. You are safe. You are wanted.

At three a.m., in the long hour when clocks forget how fast time can go, I walked the hall with her, cheek to cheek, and told her stories that weren’t about before. I told her about after, about how you can build a whole life out of a pile of endings, about the sound a door makes when it opens to a room you didn’t think you deserved.

I wrote. Not just in spiral notebooks, but for people who sent emails that said We’d like to publish this. Stories about women who stay and then go, about kitchens and phones and the way a body can be both a battlefield and a nursery. I built a little desk beside Clara’s playmat, and she kicked at the air while I typed paragraphs into our future. When I read lines aloud, she smiled as if I’d gotten them right.

Sometimes grief visited like weather you can’t schedule around. On those days, I strapped Clara into her stroller, opened the front door, and let the sun clarify my face. “Look what we built,” I told her. “Just us.”

He tried twice more—once with an apology that had notes of performance and once with an argument that had notes of panic. “I made a mistake,” he said at the door.

“You made a series of decisions,” I corrected. “This is where they led.”

I closed the door and didn’t cry. Not because I’m made of steel. Because I had a baby to feed in twenty minutes and a deadline to hit by nine and a life to live between those two points.

Spring found us ready to be seen again. The grocery store cashier learned our names. The barista learned that I take half-sweet and that Clara likes to stare at the espresso machine like it’s a Las Vegas fountain. We went to the park and I watched other mothers watching other babies, and I felt the first clean, uncomplicated easiness I’d felt in years—a bright ribbon of a feeling I was not about to question.

One afternoon, Linda stopped by with a stack of files and a glint. “We want you to lead the launch,” she said. “You’ve earned it.”

I thought about the table I had set for a man who had planned to leave. I thought about the kitchen and the voicemail and the sound a life makes when it turns. “Yes,” I said without hesitation.

We celebrated with takeout on the living room floor. Clara gummed a spoon. I cried a little into my noodles in the way you do when you realize the universe didn’t forget your address.

April from parenting class became a real friend—the kind who will show up if your car won’t start and the kind who will tell you the truth about sleep schedules with a kindness that doesn’t make you feel like a bad mother. We took turns holding each other’s babies so the other could have two free hands to drink coffee and remember their own.

Eleanor sent a birthday card for Clara’s first, the edges too crisp, the script too careful. Wishing you every joy, it said. No mention of me. No return address. I took a picture of Clara in a paper crown and didn’t send it because some bridges look like roads until you try to drive across them.

Rachel met someone. He was good. He carried chairs after dinner without being asked and laughed at himself when he tried to assemble a playpen without instructions. “He’s a real one,” she said. We toasted with cheap champagne because that’s what you do when people who deserve nice things get them.

On Clara’s second birthday, we ate cake for breakfast and ran through the sprinkler in the afternoon because childhood should be sticky and loud. I stood in the yard and took a picture of her running in the light that has only ever belonged to late June, and I cried because it had all happened without me noticing: I had become happy.

Not movie-happy. Not confetti-happy. The kind of happy that reads to a toddler and shuts the laptop at five and texts a picture of a ridiculous sandwich to a group chat and pays the mortgage on time and lights a candle on a Tuesday because the living room is clean, yes, but also because we lived.

A final letter came from Ethan. It had no sharp edges. He said he was sober, said Madison had left, said he did not expect anything, said he understood what he had broken, said he hoped Clara would one day want to know him. I wrote back two sentences: I’m glad you’re working on yourself. When she is old enough to ask questions, I will tell her the truth and let her decide.

It turned out the hardest part of forgiveness was not offering it to him. It was offering it to myself—for not knowing, for not leaving sooner, for needing a voicemail to be the thing that picked me up by the shoulders and turned me around.

Years later, when Clara was tall enough to use her own step stool at the sink, she asked where her daddy lived. I dried my hands and told her the true story with all the proper names. I told her that some people love well and some people don’t, and that the most important thing she could ever do was learn the difference and act accordingly. I told her that I had loved her father and that he had loved me and that sometimes love is not enough when honesty is not there to hold it up. She nodded solemnly and announced she wanted spaghetti for dinner.

After she went to bed that night, I sat in the kitchen—the same one that had once been an evidence locker—and thanked the rain. I thanked the pipe that had finally decided to work and the water that had splashed where it wasn’t supposed to and the phone that had betrayed a man who had betrayed himself first. I thanked the part of me that had listened and then moved.

The house is different now. There are crayon marks on the baseboards and library receipts on the fridge and a perpetual stack of laundry that I have stopped resenting. There is laughter in the hall that has nothing to do with performance, and music in the living room that isn’t trying to make anyone forget where they’re standing.

Sometimes, on afternoons when Clara falls asleep in the car and I drive an extra ten minutes just to let her nap, I pass neighborhoods where other versions of me still live. I don’t hate them. I don’t rush to rescue them. I send them a kind of quiet energy that says: When you’re ready, you’ll know. You will not miss the door. It will be bright enough for both of you.

I thought the surprise I had been planning was a crib and a name and a man twirling me around our kitchen. The surprise turned out to be me—stronger than I believed, kinder than I expected, unwilling to end the story in the middle. I had wanted to surprise my husband. Instead, I surprised myself.

If you’re reading this in a kitchen that looks a little like mine did then, if you are holding something you’re not sure you can hold, if you’ve just heard a voice through a door that changed your weather: you are not done. You are not ruined. You are allowed to choose again. You are allowed to set a table for a different life.

In the middle of the celebration, I went looking for a husband to surprise and found a truth I didn’t want. The life that came next was not the one I’d planned. It was better: honest, quiet, and full of a child who laughs with her whole body. I did not get the ending I thought I’d bought with casseroles and patience. I got a beginning I’m proud to live in.

And when the rain comes now, it feels less like needles and more like blessing. I open the window, let it in, and I wash the dishes slowly—no longer afraid of what the water will turn on.

Part 3

By the time Clara was five, she had become a tiny, unstoppable narrator of our lives.

“Once upon a time,” she announced one Saturday morning from the couch, clutching a cereal bar like a microphone, “there was a mom who was very strong and a girl who was very fast and they lived in a house with too many books and not enough cookies.”

“Hey,” I called from the kitchen, pouring batter into a pan. “We have plenty of cookies.”

“Not for my heart,” she said gravely, then dissolved into giggles.

She’d started kindergarten that fall, marching into the classroom with a backpack half her size and a confidence twice mine at that age. On the first day, I watched her take a deep breath, scan the room, and pick a seat next to a boy no one else was sitting by.

He looked up, startled.

“I’m Clara,” she said. “I like stories and jelly sandwiches. What do you like?”

He blinked and then smiled. “Dinosaurs.”

“Cool,” she replied. “We can be friends.”

I’d gone back to my car and cried—not because I was sad, but because I knew how much it costs to cross a room and sit next to loneliness, and she did it like it was the most natural thing in the world.

She asked about Ethan more that year.

“Why don’t you love him anymore?” she asked once from the backseat, legs swinging, eyes on the passing houses.

I gripped the steering wheel a little tighter.

“I don’t stop loving people like a light switch,” I said. “But I did stop letting his choices make my life small.”

She considered that. “So, like, you still care about him, but you love you and me more.”

“Yes,” I said. “Exactly like that.”

She nodded, satisfied, then asked if we could get pizza for dinner.

The first time Ethan saw her in person, she was six.

It was my idea.

She’d been asking more pointed questions: did he forget my birthday, does he know what I look like now, does he remember my favorite color. I could have kept stalling. I could have lied. Instead, I called my lawyer, then Ethan’s, then Ethan.

“We can meet,” I said. “On my terms. Public place. Short. If you make this about you and me, I walk.”

There was a pause on the line, long enough for me to count the tiles on the kitchen floor twice.

“I understand,” he said. His voice sounded older, like someone had scraped some of the polish off. “Thank you.”

We met at a park halfway between our cities, the kind with a duck pond and a playground and enough parents around that I knew no one would make a scene. Rachel came with us and sat on a bench with a book she barely pretended to read.

Clara wore the yellow dress she called her “sunshine armor.” She was quiet on the drive, which was rare enough to be its own weather pattern.

“You don’t owe him anything,” I reminded her as we pulled into the parking lot. “Not a hug, not a smile, not forgiveness. You get to decide.”

“I know,” she said. “But I want to see what his face does when he sees me.”

He was already there, hands shoved into the pockets of a jacket that looked a little too big. His hair had more gray at the temples. His shoulders were less certain. When he saw us, something like awe and regret crashed together in his expression.

“Hi,” he said, voice rough.

Clara regarded him as if he were a painting she wasn’t sure she liked yet.

“You’re taller than in the pictures,” he added, then winced. “That was a stupid thing to say. Sorry. I’m… I’m nervous.”

“Good,” she said. “Me too.”

He laughed, surprised.

I stayed a few steps away, arms crossed loosely, close enough to intervene, far enough to give her room.

He didn’t reach for her. He didn’t cry. He just sat down on the bench nearby when she sat, leaving a respectful gap between them.

“I brought you something,” he said, awkwardly holding up a small, wrapped package. “You don’t have to like it. Or keep it. I just… wanted to bring something that was about you, not me.”

She tore the paper off with the efficiency of a six-year-old and held up a sketchbook and a pack of colored pencils.

“I remembered your mom said you like to draw,” he said. “The lady at the art store said these don’t break as easy.”

Clara flipped through the blank pages, thumb making the paper whisper. “Thank you,” she said, polite but not performative.

“You’re welcome,” he said, and looked like he might break anyway.

They talked. About school. About her favorite books. About how she’d once eaten an ant on a dare and regretted it for a week. He listened like it was all important. To her, it was.

He didn’t talk about the divorce. He didn’t talk about Madison. He didn’t ask to hold her or to be called Dad. At one point, Clara glanced over at me, eyes asking, Are you okay?

I nodded. I was.

After half an hour, I checked my watch. “Time,” I said gently.

Clara hopped off the bench.

“Can I draw you something sometime and mail it?” she asked Ethan.

He swallowed. “I’d like that very much,” he said.

In the car, she buckled herself in and stared out the window for a minute.

“Well?” I asked.

She shrugged. “He’s… sad,” she said. “And kind of funny. And kind of small.”

“Small?”

She scrunched her nose. “Like, inside. Like his feelings are all squished up.”

“Yeah,” I said. “That feels right.”

“Can we get ice cream?” she asked.

“Of course.”

On the way to the ice cream shop, my phone buzzed.

Thank you, Ethan had written. For trusting her. For not turning her into a weapon. I’m going to spend the rest of my life trying to be the man she thinks she met today.

I didn’t reply. Some messages are just meant to be read, not answered.

Life settled into its new rhythm. Meetings and school pickup and late-night fevers and deadlines and the occasional email from Ethan with a joke or a photo of a stray cat he’d befriended on a job site.

I stayed single longer than anyone expected.

“You’re allowed to want someone,” April said over coffee one day as our kids smeared playdough into the cracks of her dining table. “You know that, right? Wanting help doesn’t mean you failed at independence.”

“I know,” I said. “I just… like this. Us. Me and Clara. I don’t want to invite anyone in who doesn’t make it better.”

“Then don’t,” she said. “But if someone does make it better… maybe don’t slam the door in his face.”

I rolled my eyes and changed the subject.

The person I didn’t slam the door on when he showed up wasn’t a stranger. It was someone who’d been in the background of our lives so long I’d almost stopped seeing him.

His name was Jonah.

He owned the bookstore on the corner, the one with the crooked shelves and the resident cat. He was the one who always tucked an extra sticker into Clara’s bag when we bought her a new chapter book and who always remembered what I’d read last.

“You strike me as someone who rereads novels more than you reread emails,” he’d said once, which should not have felt like a compliment and yet somehow did.

One rainy Thursday, our power went out. Clara thought it was magic; I thought it was an emergency. The fridge. The heat. My laptop battery at 12%.

“I’m bored,” she declared after an hour of flashlight puppet shows and shadow stories.

“We’ll go somewhere with lights,” I said, grabbing our coats.

“Like where?”

“Like… the bookstore.”

The bell chimed when we stepped in. The warmth was instant. Jonah looked up from behind the counter, where he was wrestling with a stack of returns.

“Power’s out?” he guessed, taking in our damp hair.

“Yep,” I said. “We’re refugees.”

“Welcome to the Republic of Paper,” he said. “We have heat and three-dollar cocoa.”

“Sold,” I said.

Clara disappeared into the kids’ section with a speed that suggested she’d have found her way even in the dark.

I leaned against the counter, exhaling. “I forgot what quiet felt like,” I admitted.

He poured cocoa into a paper cup and slid it toward me. “You never forget,” he said. “You just misplace it for a while.”

I smiled into the steam. “You always talk like a man who lives between chapters.”

“Occupational hazard,” he said. “You start seeing everything as a story. Even outages.”

He hesitated, then added, “So, how’s your story these days? Last time you were in, you said you were finishing revisions on something.”

I’d told him, in a moment of uncharacteristic openness, about an essay collection I’d been working on. About kitchens and phones and celebrations and the quiet corners of grief.

“I turned it in,” I said. “My agent’s sending it out. I’m trying not to picture editors using it as a coaster.”

“They’d be fools,” he said. “You write like you’re pressing your hand into wet cement. It stays.”

Heat crept up my neck that had nothing to do with the cocoa.

We talked. About books and deadlines and the weird era of school picture day. When Clara came back with an armful of picture books, he rang them up and slipped in an extra one “by accident.”

Outside, the rain had softened to a mist. The power at home flickered back on while we were pulling into the driveway.

That night, after Clara was asleep, I found myself thinking about the way Jonah had looked at her when she’d explained the entire plot of a story she hadn’t finished yet—with patience and genuine interest, not condescension.

“You’re doing it,” I told myself sternly in the bathroom mirror. “You’re imagining things.”

But the next time he wrote a note on my receipt—Don’t forget to read page 147 twice—I didn’t roll my eyes. I smiled.

Part of me was still in that hallway outside Ethan’s office, listening to a voice meant for someone else. Part of me always would be. But another part of me—the louder, healthier part—had started to believe that what happened there didn’t have to be the last word on love.

The universe apparently agreed, because three weeks later, I got an email from my agent with a subject line that didn’t feel real.

Offer.

I opened it with shaking hands.

They loved it, she wrote. They want to publish it. Full collection. Good advance. They think this is the start of something.

I laughed, and then I cried, and then I called Rachel, who screamed, and then I called my parents, who both tried to talk at once.

When Clara came home from school, I swung her in a circle.

“What happened?” she shrieked, laughing.

“Someone wants to make my book into a real book,” I said. “With pages and a cover and everything.”

“So it won the contest?” she asked, because in her world, you only got prizes by beating someone else.

“Kind of,” I said. “But the real prize is… we might be able to fix the roof and still afford soccer.”

She gasped. “We’re rich?”

I snorted. “We’re… okay. And that’s more than enough.”

We celebrated that night with grilled cheese and tomato soup and a dance party in the kitchen. I spun her under my arm. She spun me under hers. The lights flickered once and stayed on.

In the middle of that celebration, I caught my reflection in the window—hair wild, cheeks flushed, eyes bright—and realized I didn’t feel like a woman waiting for the next disaster. I felt like someone standing in the middle of her own life, fully present.

Later, after I tucked Clara in, my phone buzzed.

Congrats, the text read. Rachel again? Another friend?

Unknown number.

Who is this? I wrote.

A minute later: Sorry, it’s Jonah. Got your number from the order form your publisher sent over—we’re going to carry your book. That was probably a weird way to get it. I just didn’t want to wait until you came in to say how proud I am.

My stomach did something inconvenient.

Thank you, I typed. And then, before I could overthink it: I owe you cocoa.

Deal, he wrote. For the record, I’d have cheered this loud even if I didn’t hope to be in the acknowledgments.

You are, I replied, and smiled at his next message: Guess I better buy a nicer shirt for the launch party.

The word party used to make my chest tighten. Now it sounded… like an opportunity.

Part 4

The launch party was nothing like Eleanor’s 60th.

For one, it was in a bookstore, not my dining room. For another, no one there was pretending to like me out of obligation.

The shop was packed in the way that made the fire marshal nervous and my inner thirteen-year-old ecstatic. Friends from work. Parents from school. People from the community center. Strangers who’d read an excerpt online and decided to show up. My parents stood near the back, beaming. Rachel was up front with April, both armed with tissues and their phones on camera mode.

Shelves had been pushed aside to create an aisle of folding chairs. At the end of it, a small podium waited, my name printed on a poster beside it, the book cover shining from a stack.

In the Middle of the Celebration, the title read, in looping script, I Wanted to Surprise My Husband.

I’d fought for that title. My editor had worried it was too long, too specific. I’d insisted.

“That’s where it started,” I’d said. “In the middle of a party that wasn’t about me. That’s the night everything changed.”

She’d relented. “You’re the one who has to live with it,” she’d said. “Besides, it’s a hell of a hook.”

Jonah moved through the crowd, checking on the coffee urn, straightening a stack of books, whispering something to the high school kid manning the register. He’d put on a navy button-down that did, in fact, look newer than his usual flannels.

“You ready?” he asked when he finally reached me.

“No,” I said. “Yes. Maybe.”

“Good answer,” he said. “Ready people are boring.”

I laughed, nerves untying a little.

Clara had insisted on choosing my outfit. We’d settled on a simple black dress and a bright scarf.

“You look like a writer,” she said proudly, as if she’d invented the concept.

When it was time, Jonah tapped the mic.

“Thank you all for coming,” he said, voice carrying easily. “I opened this store because I believe books save people. Tonight we get to celebrate a book that did that work before it was even bound. Please welcome our very own Anna.”

The applause hit me like a wave.

I stepped up to the podium, fingers brushing the worn wood. For a heartbeat, the air shifted, and I was back in my kitchen, listening at a door that had never been meant to be a window.

I took a breath.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m Anna. And I wrote this book because one night, in the middle of a celebration I was hosting for somebody else, I realized my life was happening in the next room without me.”

A ripple of recognition moved through the crowd. People shifted in their seats. A woman in the second row pressed her lips together like she was holding in a story of her own.

“I thought that night was the end,” I went on. “Spoiler alert: it wasn’t.”

I read. Passages about Eleanor’s party. About the hallway. About the office door and the voice on the phone. About the kitchen sink, the phone, the decision. About Clara’s first cry. About the way rebuilding looks like laundry and court dates and asking your boss for a different schedule.

When I reached the part where I wrote, I thought the surprise I’d been planning was a crib and a name and a man twirling me around our kitchen. The surprise turned out to be me, my voice shook.

I looked up and saw tears in more eyes than just my mother’s.

After, during the signing, people came through the line with their books open to the title page and their hearts open to the air.

“My husband left me last year,” one woman whispered. “I thought I was crazy for not seeing it. Thank you for making me feel less stupid.”

“You’re not stupid,” I said, meeting her eyes. “You were generous.”

A man about my father’s age said, “I was Ethan once. I’m trying not to be anymore. Your book hurt in the right way.”

A twenty-something with purple hair said, “My mom stayed. I wish she’d had this.”

“I’m glad you do,” I said.

Clara hovered nearby, carefully arranging the stack of signed copies, occasionally whispering, “That’s my mom,” to anyone who looked like they might not know.

At the end, when the last book was signed and the last cookie was eaten, Jonah handed me a glass of cheap champagne.

“You did it,” he said.

“We did,” I corrected. “You made a space for it.”

He shrugged. “It was going to exist with or without these walls.”

He hesitated, then added, “I’m… uh… supposed to ask you something.”

“Oh?” I teased. “Is this where you tell me you’re secretly married and ten kids are going to come out of the stockroom?”

He snorted. “God, no. I can barely keep track of my ferns.”

He took a breath, and suddenly the room felt quieter, even though people were still talking, still stacking chairs.

“I’ve been thinking,” he said. “About timing. About how you’ve spent the last few years building something sacred out of wreckage. About how unfair it would be to come in and ask for space in that before you were ready.”

He looked me straight in the eye.

“I like you,” he said. “A lot. I like Clara. I like the version of myself I am when I’m around you. I don’t need an answer tonight. Or this month. Or this year. I just needed to say it out loud, so it isn’t living in my head rent-free.”

My heart did its old, familiar stutter. But this time, it wasn’t fear. It was… possibility.

“You picked an interesting setting,” I said, glancing around. “Very public.”

He winced. “Yeah, the timing could be better. I blame the champagne. And your reading. It was like watching someone run a marathon and then being like, ‘Hey, want to go for a walk?’”

I laughed, a little breathless.

“Jonah,” I said. “I like you too. I like that you never once tried to fix me. I like that you stock my book next to the authors you know intimidate me just to make a point.”

He grinned. “You noticed that.”

“I notice everything now,” I said. “It’s kind of my thing.”

I took another breath. I thought about the woman who’d stood outside an office door and the woman who’d stood behind a podium. They were both me. Only one of them had any business answering this question.

“I’m not looking for someone to rescue me,” I said. “I don’t need rescuing. But I am… open to someone to walk next to. Slowly. With rest stops.”

His shoulders dropped, tension he probably hadn’t realized he was holding dissolving. “I can do slow,” he said. “I shelve Russian novels for fun.”

I laughed.

“Okay,” I said. “Then let’s… see.”

He touched his glass to mine. “To seeing,” he said.

“To seeing,” I echoed.

On the drive home, Clara chattered nonstop from the backseat about how weird it was to see my face on a poster.

“Does this mean you’re famous?” she demanded.

“Not really,” I said. “It means I said some things out loud that other people were already thinking.”

“That’s what famous is,” she argued. “Just… louder.”

She fell asleep with her head against the window, clutching the bookmark Jonah had given her that read: Some stories save us. Some stories are us.

I carried her to bed, then went back to the kitchen.

The table was cluttered with discarded gift bags and a stack of unsent thank-you cards. I cleared a space and sat down. The hum of the fridge, the tick of the clock, the faint sound of a car passing outside—all of it felt like a soundtrack I’d finally chosen.

My phone buzzed.

You were incredible tonight, the message read.

From Ethan.

I stared at it for a long moment.

Thank you, I wrote back. I meant everything I said.

I know, he replied. I’m glad you’re telling it. Maybe… it’ll help other Annas leave sooner. And other Ethans wake up before they burn everything down.

Maybe, I typed. For both our sakes, I hope so.

We didn’t talk about Clara. We didn’t fall into old patterns. We just existed in that small, strange overlap between past and present, two people who had once shared a life and now shared a story.

I set the phone down and looked around my kitchen.

Once, this room had been a stage set for other people’s celebrations. Now it was command central for mine.

I stood up, turned off the light, and went to bed.

Part 5

Five years later, I stood in a different kitchen, in a different house, frosting a cake I had baked with my daughter and my almost-husband, and realized I had finally rewritten what celebration meant.

The house was small but ours—mine and Clara’s, with room folded in for Jonah like a carefully written chapter. We’d bought it together the previous spring, trading in my old mortgage and his apartment above the store for a patch of yard and a kitchen with enough counter space for three people to make a disastrous amount of cookies at once.

The counters were currently dusted with powdered sugar. The sink was full. The floor bore the sticky footprints of a twelve-year-old who still had no concept of how to stay in one place while eating.

Clara perched on a stool, wielding a piping bag like a weapon.

“Not too much,” I warned.

“This is art,” she said, looping another swirl of buttercream along the edge. “Art cannot be contained.”

“It can if we want it to fit candles,” Jonah pointed out, leaning against the fridge, tie slung over his shoulder, shirt sleeves rolled up.

He was wearing the suit we’d bought for court appearances and weddings. Today it was for the latter.

“Remind me why we’re doing this at home and not at some fancy venue where other people clean up?” he asked.

“Because I promised myself,” I said, smoothing the frosting along the side of the cake, “that the next big celebration I hosted under my roof would be about me. And the people I chose.”

He nodded, expression softening.

“Also,” Clara added, “because Grandma June said if we spent money on chair covers, she’d disown us.”

“Valid,” Jonah conceded.

It was our wedding day.

We were keeping it small. Backyard, fairy lights, a taco truck parked at the curb, a rented arch we’d drape with flowers my mother and April were currently arranging like they were auditioning for a gardening show. No assigned seating. No DJ. A playlist Clara had curated of Motown, indie folk, and three Taylor Swift songs she insisted were “legally required.”

“You good?” Jonah asked, pushing off the fridge and coming over to rest his hand on the small of my back.

I thought about it.

I thought about Eleanor’s birthday. The hallway. The office door. The conversation I wasn’t supposed to hear.

I thought about the kitchen afterward, the way the water had hit the phone, the way my own voice had sounded when I’d said, “I know.”

I thought about the hospital, Clara’s first cry, the nights alone, the parent-teacher conferences, the edits, the launch party, the park bench with Ethan, the bookstore’s hum, the email that had started with Offer.

I thought about the woman I had been in each of those scenes. How often I’d mistaken endurance for love. How long it had taken me to understand that leaving wasn’t failing a promise; it was honoring a deeper one.

“Yes,” I said now. “I’m good.”

He kissed my temple. “Then I’m good.”

Clara hopped off the stool, wiped her frosting-covered fingers on a dish towel, and surveyed us with a critical eye.

“You’re going to make people cry,” she said. “In a good way.”

“That’s sort of your mom’s brand,” Jonah said.

“Rude,” I said. “But fair.”

Guests started arriving in little clusters. My parents, carrying folding chairs and a cooler that clinked. Rachel and her husband, with their two kids arguing about who got to hold the rings for a second. April with a tray of deviled eggs and a look that said she’d kill anyone who messed with me.

Eleanor came, too.

That had been a whole story on its own.

She’d reached out a year earlier, after seeing an interview I’d done on local TV about the book and the way communities can quietly enable a certain kind of betrayal.

I owe you an apology, she’d written in an email so formal it could have been framed. For not seeing. For not wanting to see. For letting my love for my son excuse what he did to you. If you are ever willing to speak to me, I would like the chance to say that to your face.

I’d stared at the screen for a long time, hearing her voice in my head: Everything is perfect. And later: How could you do this to our family?

In the end, I’d said yes. Not for her. For me.

We’d met at a quiet café at an hour when nobody we knew would be there. She’d looked smaller, too. Softer at the edges. Her hair had thinned. Her hands had trembled slightly when she’d lifted her cup.

“I thought he was happy,” she’d said, eyes damp. “I thought you were dramatic. I thought… if I admitted anything was wrong, it meant I had failed as a mother.”

“You didn’t cheat for him,” I’d said. “You didn’t pick up the phone in that office.”

“No,” she’d agreed. “But I raised a man who thought he was entitled to everything he wanted without consequence. I praised him for charm and never for telling the truth when it cost him something. That’s on me.”

I hadn’t absolved her. But I’d accepted her apology. She’d been at three of Clara’s soccer games since.

Now, in my backyard, she approached me slowly, cane tapping the grass.

“You look radiant,” she said, and for once, there was no edge to it.

“Thank you for coming,” I said.

“Thank you for inviting me,” she replied. Her eyes slid to Jonah, who was adjusting the arch, tongue between his teeth in concentration. “He seems… good.”

“He is,” I said simply.

She nodded once. “I’m glad,” she said. “Truly.”

The ceremony itself was short.

Clara walked me down the “aisle”—a path between two rows of mismatched chairs—holding my hand with the solemnity of someone escorting a queen.

“You sure about this?” she whispered, loud enough for the first row to hear.

“I am,” I said.

“Okay,” she said. “Because if he ever hurts you, I know where he works and I can rearrange his shelves into chaos.”

“You’re terrifying,” Jonah murmured when we reached him. “I love that about you.”

Our officiant was a judge from the family court I’d met during my divorce, who’d become an unlikely ally. She spoke briefly about second chances and the bravery of staying when it’s right and leaving when it’s not.

Then it was our turn.

“I, Jonah,” he said, looking right at me, “promise not to make you smaller so I can feel big. I promise to listen when you say you’re tired, not just when you clap. I promise to tell you the truth even when it makes me look bad. I promise to celebrate you when it’s your party and clean up with you when it’s not.”

I laughed through my tears.

“I, Anna,” I said, “promise not to disappear into taking care of everyone else. I promise to let you carry some of the weight, even when my instinct is to apologize for it. I promise to tell you when I’m scared instead of pretending I’m fine. I promise to remember that this is a choice we make every day, not a default we fall into.”

We exchanged rings. We kissed. People cheered and whooped and wiped their eyes and then immediately started lining up at the taco truck because feelings are easier to process with guacamole.

Later, when the sun dipped low and the fairy lights flickered on and someone’s kid knocked over a cup of lemonade and nobody panicked, I slipped away for a minute.

The house was quiet inside, the way a stage is quiet between acts.

On impulse, I walked down the hall to the small room at the end that Jonah had claimed as his “office.” It was a modest space—cheap desk, sagging bookshelf, a bulletin board with more ideas pinned to it than he’d ever have time to execute.

The door was half-open, lamplight spilling across the floor.

I stopped in the same place I had all those years ago outside Ethan’s office.

My heart thudded, not with fear this time, but with muscle memory.

I listened.

Inside, Jonah was on the phone.

“Yes, Mom, I’m sure,” he was saying, laughing. “Of course I’m sure. I wouldn’t be standing here in a suit sweating through my shirt if I wasn’t.”

He paused, then added, “Because she’s… home. Because when I picture any version of the future where I’m not walking next to her and Clara, it looks… wrong. Because she doesn’t need me, and she still chose me. That’s the biggest honor I’ve ever had.”

My throat tightened.

He must have heard my little inhale, because he turned.

“Busted,” he said into the phone. “She heard me. I’ll call you later.”

He hung up and opened his arms.

“You spying on me at our own wedding?” he teased.

“Just making sure I don’t need to burn another man’s office down,” I said, stepping into his embrace.

He sobered, pressing his forehead to mine.

“You will never have to listen at doors in this house,” he said. “If there is something you need to know, you’ll hear it sitting next to me on the couch, eating cereal out of the box.”

“I know,” I said. “But for what it’s worth… I like what I heard.”

He smiled. “Good. Because my mother thinks I talk too much about you.”

“She has excellent taste,” I said.

We stood there for a moment, in the doorway between past and present, and I realized something I wish I could go back and whisper to the woman I used to be:

It’s not that you’ll never hurt again. It’s that one day, you’ll hurt and also be happy. You’ll remember and also move forward. You’ll walk past an office door and not flinch.

“Come on,” he said, taking my hand. “Your daughter is about to start the playlist without you and you know she’ll roast us in her speech if we’re late.”

We stepped back into the yard.

Clara stood on a chair, clinking a fork against a glass like she’d been doing it her whole life.

“Attention!” she called. “I have prepared remarks.”

Groans and laughter.

“Keep it under ten minutes!” Rachel shouted.

“I make no promises,” Clara said, then grinned. “Okay. So. Once upon a time, my mom was married to a person who did not deserve her. Then she heard something she wasn’t supposed to hear and she did the scariest thing a person can do: she left. And she didn’t just leave. She built something. Me. This house. This whole buffet.”

People laughed.

“She taught me that love is not about staying no matter what,” Clara went on. “It’s about staying where you can be yourself. Jonah,” she turned to him, “thank you for knowing that already and not making her teach it twice.”

He laughed, blinking fast.

“Anyway,” she finished. “I’m really glad we’re all here. I’m really glad my mom got surprised in the worst way once, because ever since then, she’s been surprising herself in better ones. To Mom and Jonah: may your fights be funny and your tacos never run out.”

She raised her glass of sparkling cider.

Everyone echoed the toast.

I felt the words settle over us like a blessing.

Later, after the guests had gone and the yard was a battlefield of paper plates and stray napkins, after my parents had gone to bed at their hotel and Rachel had left with a Tupperware full of leftover carnitas, after Clara had finally fallen asleep with her dress half unzipped and her speech crumpled on the nightstand, I went back to the kitchen one last time.

The sink was full. The counters were sticky. My feet hurt. My hair was coming undone.

I turned on the tap.

Water rushed, clear and cold, splashing over plates and glasses, catching the light from the window.

My phone, on the counter, buzzed.

A voicemail.

I smiled, picked it up, and pressed play.

“Hey,” came my own voice, younger and thinner, from a recording I’d forgotten I’d made years ago when my therapist had suggested I talk to myself like a friend. “If you’re listening to this, it means you’re somewhere hard. Just… remember you’ve done hard before. Remember the kitchen. Remember the office. Remember the choice you made. I’m proud of you. I love you. Keep going.”

I laughed, a little choked.

“Already did,” I told her. “You’d like it here.”

I set the phone down, rolled up my sleeves, and started on the dishes.

In the middle of the celebration, all those years ago, I’d gone looking for my husband and found a truth that broke me.

In the middle of this one, I’d gone looking for my almost-husband and found a different truth:

I was never really looking for a man in an office.

I’d been looking for myself.

And this time, when I found her, I didn’t let go.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

At my granddaughter’s wedding, I noticed my name tag said, “The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to have you here.”

At my granddaughter’s wedding, I noticed my name tag said, “The old lady who’s paying for everything. I’m glad to…

While I Was Washing Dishes, Water Hit My Husband’s Phone. Then His Voicemail Played. I Fell Apart…

While I Was Washing Dishes, Water Hit My Husband’s Phone. Then His Voicemail Played. I Fell Apart… Part 1 The…

On My Wedding Morning, My Mom Burned My Dress With A Candle. So I’d Look Less Pretty Than My Sister

On My Wedding Morning, My Mom Burned My Dress With A Candle. So I’d Look Less Pretty Than My Sister…

Mom Kicked My Daughter’s Leg Out During Dance Recital And Laughed — Now She Matches Her Worthless Life

Mom Kicked My Daughter’s Leg Out During Dance Recital And Laughed — Now She Matches Her Worthless Life Part…

My Parents Slap Me for Buying Shoes for My Son Instead of Contributing to My Sister’s Honeymoon Fund

My Parents Slap Me for Buying Shoes for My Son Instead of Contributing to My Sister’s Honeymoon Fund Part…

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was…

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was… Part…

End of content

No more pages to load