In The Courtroom, I Smiled—Because My Husband Never Knew The Secret I’d Kept For 20 Years…

Part One

The old college hall in Reinbeck still smelled faintly of lemon oil and paper programs. Sunlight fell through tall mullioned windows in wide, generous bands—good light, the kind that makes even a crowded room feel intimate. Families rustled and whispered, cameras chimed, and somewhere to my left a woman sobbed into a man’s shoulder as if she’d just been given back the entire world.

I could not take my eyes off the young man stepping into the light at the front of the stage.

Michael.

My son crossed the boards with a stride I recognized from a hundred smaller triumphs—the first day he tied his shoes without help, the science fair ribbon he pretended to shrug off, the letter that said Yes from the last program he’d dared to hope for. The crimson honors sash lay easy across his shoulders. When the dean placed the diploma in his hand, it looked like a scepter.

Around me, the hall rose to its feet. I clapped until my palms stung. Someone’s hat slipped backward. Someone’s bouquet knocked into the back of my head and I apologized for being in the way of their joy.

Inside, my chest ached with something heavier and more private than pride.

In less than a week, I would no longer be Mrs. Whitaker.

Twenty years reduced to a courtroom docket, a file, a signature that would unthread a life the way you unravel a hem: fast when you know exactly where to pull. The irony was cruel—my son’s future opening like a field while my marriage narrowed to a corridor with a door at the end.

Thomas sat several rows behind me, as he always sat for the things that belonged to me rather than to him: present-distant, suit immaculate, jaw set in a way that looked like effort if you didn’t know it was indifference. He didn’t clap like I clapped. He didn’t smile as though the light had chosen our son to carry it farther than we ever could. He never had.

To Thomas, Michael was not and never had been his son. He tolerated the boy the way some men tolerate nice weather that interrupts their plans—pleasant, inconvenient, not differently real. I had tried to build a bridge with casseroles and holiday compromises and the quiet endurance that keeps a family calendar running on a wall. In the end, Thomas had never crossed it.

Men like Thomas do not change. Their silences become architecture; their absences acquire routine. And eventually you find another silence in your house—the one that comes when you know where he is without needing to ask.

That afternoon, however, I refused to catalog losses. I pressed my hand to my throat as Michael lifted his name out of the dean’s mouth and into the rafters, and I let pride steam through me like breath on a winter morning.

He found me in the courtyard after, diploma tied like a promise. “Mom,” he said, and then he was in my arms and I was holding on to the one thing I knew I had done right. We laughed—he, because it felt like air, me, because it felt like reprieve. Over his shoulder, I saw Thomas watching us, unreadable, already elsewhere. And I understood, suddenly and without drama: this chapter was mercifully ending. A door was closing with a sensible click. Somewhere, another had opened its hand.

I had carried a secret for twenty years. It had lived beneath my ribs like a second heart—heavy, rhythmic, impossible to silence. The week ahead would strip my name from a mailbox and my presence from a deed. But the secret? The secret was mine. And, in the courtroom, I would be the only person who knew why I could sit there and smile.

On nights after celebrations, when the house at last exhaled and darkness gathered in the corners, I could conjure him the way grief conjures anything it refuses to leave alone. Not Thomas. Not the man whose shoes sounded like closing doors. The boy before him, the fire I had met too young.

Daniel Brooks was all edges softened by loyalty. He smelled like motor oil and citrus and a bad idea I never regretted. He had a comic-book sense of justice and the kind of tenderness you expect from boys who think no one sees them. Loving him felt like standing too close to a bonfire. You stayed because of the warmth knowing the spark could find you.

The night everything changed is a slideshow: the garage behind the shops, the moon slung low like a coin, a boy from another block with a stupid grin and a stupider dare, my back pressed to corrugated tin, breath stuttering—then Daniel, sudden as thunder, a shout, a flash of blade, a fist, bone, silence. The boy didn’t stand up. Daniel didn’t run.

“Excessive self-defense,” someone said with the sort of shrug you reserve for poor boys without fathers. He was eighteen. The judge didn’t blink. Within weeks, he was a number stitched to a shirt and a walk measured by walls.

Pregnancy finds you where you stand. It found me in a mirror with my mother humming in the kitchen and my father’s pencil scratching figures that always seemed to come out right. Their respectability had a sound; I grew up to it, learned its rhythm. There was no sound for the truth I carried. I bound myself in sweaters and studied until my eyes ached. I memorized lines of Shakespeare with a hand on my stomach and told myself I could be two people for as long as it took.

I wrote to Daniel. I told him about rain and exams and nausea and hope. He wrote back with pencil and restraint. Count the days until I’m home. Protect our baby. Live for us both. He never described the yard or the noise or the way nights stretch. He used words like boards with which to build me a bridge away from what he was living.

Then, suddenly, there were no more boards. No more letters. Only a message passed through a mouth that had carried too many for men like Daniel: a fall in the bathhouse. A bench. A skull. The end.

Grief is not a word; it’s an acid. It etches you while you smile at neighbors and nod at teachers and pretend your life is still the shape it was yesterday.

And still, life demands: entrance exams, bus schedules, a borrowed room in a student dorm with three walls and a window and a desk that wobbled. I kept it together with pins and hope. Life is not a person you can ask to wait.

The pain came like weather—the first contraction a horizon-line, the next a truth. A senior passing in the hall went white, shouted, and then I was a mess on rusted wheels, a ward document lost in a stack of other small tragedies.

The hospital was the kind they keep out of brochures: peeling paint, soup that always tastes like last week, bleach that never manages to smell like clean. A nurse took my name and then my breath and then my dignity as if the three were meant to be handed over together.

They put me in a two-bed room and that’s where I met her.

Victoria Hayes arrived like money always does—flaunting the joke that it has nowhere appropriate to be. Hair like advertisement. Mouth like a blade. She told me everything without asking anything: the family with a name that unlocks doors, the suitcase of cash that serves as penance, the mandate to disappear until the problem solved itself.

“It’s all a farce,” she said, and smiled like it wasn’t one.

I screamed my son into a room that wouldn’t even look at him. Silence after silence after silence. Then a whisper: He’s not breathing. The nurse said it like a headline. She did not place him on my chest.

My grief must have been a mirror because Victoria flinched and then straightened and then leaned toward me. “Take mine,” she said.

I thought I hadn’t heard. She repeated it, the words stitched to her laugh so they wouldn’t tremble. “Take my baby. He’ll have a life with you. Mine will never have one with me.”

If you want to hate her, choose a different story. She was cruel and brittle and wounded and rich and right. In that miserable ward, no one was looking, not really. The overworked nurse glanced past us. The clipboards piled up like snowdrifts. There were no ankle tags. There was no security man at the door. There was only the humming light and a basin and the cold weight of my dead son and the hot weight of a live boy I had not made.

I prayed an apology I did not know how to compose. I kissed a forehead that would never frown and promised a grave I would never be shown. Then I lifted the crying child whose fingers curled around mine as if they had been practicing for this moment all along.

We made the exchange before dawn as quietly as a confession. The paperwork didn’t blink. Ink is blind like that. I wrote Michael where a blank wanted his name.

I built a life on that signature—night feedings, scraped knees, book fairs, the volunteer clipboard, the science camp envelope I slipped into a mailbox I could barely reach. Every time I tucked him in, the lie pressed a little harder against my ribs. Every time he laughed, the truth loosened its hold.

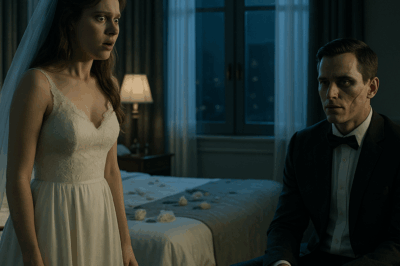

When Thomas appeared, he offered me shelter in the form of a vow that didn’t pretend to be tenderness. “I won’t love him like my own,” he said, as if realism was kindness. “But I’ll stand in the picture beside you.”

I said yes. Not because it sounded like a wedding—because it sounded like a roof.

We were competent at being married the way two colleagues are competent at a presentation they’ve given a dozen times. We tried for a child; clinics took our blood and our money and gave us words like unexplained and unlikely. The crib stayed a paragraph in a store catalog. Thomas’s patience turned to smoke; his evenings turned to elsewhere. I found out about the other life—a woman, a child, a calendar that made more sense of his absences than any sales cycle ever could—and the strangest thing happened: the rage I expected didn’t arrive. Exhaustion did.

So I worked. I carved a career out of grammar and verse, became the woman you brought your eighth-grader to when they cried over Shakespeare, the woman you hired to iron a business email so clean it landed you the contract. Bookshelves kept me steady. Michael kept me alive.

Twenty years rolled over me. I learned to fold tablecloths alone. I learned to go to sleep without listening for a key.

In the end, Thomas didn’t bruise me with a hand. He bruised me with a file folder.

We stood in the small-town courtroom that pretends to be bigger than it is and let our lawyers do the talking. His produced a deed as casually as a weapon. The apartment where my child took his first steps? Not ours. Purchased under his mother’s name. A neat trick. A clean cut.

“You’ll have a month,” Thomas said, efficient as always. Pack. Leave. Don’t make this harder than it needs to be.

It had never been easy. Still, I smiled. Not to spite him; because the weight I had carried was almost done crushing me. He thought he’d taken my home. He had no idea that the secret I’d kept for twenty years had already opened another door.

I walked out into the Hudson Valley light and made a decision on the courthouse steps. If I owned nothing, I was free to spend everything I had left on the truth.

Part Two

I saw her by accident—fate, generosity, God, or whatever it is that organizes coincidences for people who need them to arrive on time.

Victoria Hayes looked like the ruin of the girl I remembered. The golden hair thinned, the arrogance stripped to something sharper and less decorative. We were two women in a café on a Reinbeck corner pretending the weather was a safe topic.

“I’m dying,” she said finally, the words as plain as the tea in her cup. “Cancer. It doesn’t take bribes.”

She had watched Michael, she admitted. From a distance. So the story goes. “You did what I could not,” she said, and when she said mother the way a person says mercy I forgave her for having been braver than me that night. Or more cowardly. Or the same.

She had a will. Of course she did. A villa in Cyprus, the sort of phrase that sounds like a plot twist in a paperback you lie about reading. Accounts. Investments. She wanted them to be mine.

“Why?” I asked for the sake of ritual, though I understood perfectly well. The only repentance some people are allowed is generosity.

“Because you stayed,” she said. “Because paper is paper and the boy is yours.”

She died months later. The lawyer arrived with an expression that conflated grief and professionalism. He opened his case and poured a future onto my table. I touched the stack of pages as if it might flinch.

Then I told my son.

I did not dramatize. I did not eulogize. I spoke the facts like a woman laying out instruments on a tray: the hospital ward with its stuttering light, the cold weight I kissed goodbye, the offer I could not refuse, the signature that lifted him from one life into another.

I braced myself for the blow—the recoil, the betrayal, the question you fear the most Who am I to you, then?

Michael stood up, crossed the kitchen, and knelt like a man who knows which side his heart is on. “You are my mother,” he said into my hair. “You always were.” No one tells you how much a simple sentence can weigh.

We moved through two kinds of mourning together—the baby who never drew breath and the twenty years of fear that had finally let go. On the other side of those tears, there was a plan: he would finish his work; he would marry the girl who had stood at his lab bench through examinations and doubt and joy (Emily, who moved through my kitchen as if she’d been born to know where I kept the cinnamon). I would take a trip with a lawyer who had made my name legal in a country where bougainvillea throws a tantrum against whitewashed walls and the sea insists on being an adjective.

The first time I saw the villa, I laughed out loud because sometimes life insists on satire. Blue shutters. A terrace engineered for morning coffee and late confessions. A sea that does not accept the word no from the horizon.

We moved in together like a declaration—three generations and a dog none of us intended to adopt. The villa began to sound like people. Mark evaporated from our lives not with a slam but with a failure to appear. I wish him nothing. I wish myself quiet.

Cyprus is a good place for ghosts. The dead let you nap in the afternoon there. I let the Mediterranean organize my days. I taught English to tourists who wanted to order wine without embarrassing themselves and to a boy who brought a notebook full of lyrics instead of vocabulary words. I planted herbs in the courtyard because nothing heals quite like tearing leaves from a stem and having the scent insist you’re already forgiven.

That’s when he arrived at my door asking if the lesson advertised on the hand-scrawled card in the bakery window was real.

Samuel Green was not young. He was not beautiful in the way that makes passersby pretend not to look. He was marked by fire—lips that had learned to speak around skin more tender than most men ever admit to having, hands that carried the memory of heat. But his eyes. Some things find you twice if you let them. Daniel lived there, not as a resurrection but as a permission.

“We can start with the present perfect,” I said, because teacher is a muscle you never lose. We spent evenings conjugating and laughing and discovering that idioms are just poetry that got too practical. He asked questions that assumed I had answers. He drank tea too hot and told me the sea made him less afraid.

Love did not ambush me this time. It walked at my pace and asked if the road felt right under my feet. It did.

I will not pretend the past stopped aching. Sometimes, holding my granddaughter, I would close my eyes and see a cold bassinet at the far side of a room that still smelled like bleach and soup, and guilt would prickle my skin like sun. I never stopped saying the name I never gave out loud. I never stopped telling the air the story of that night so that someone would keep it safe besides me.

But grief and joy made room for each other at my table. That is the miracle age gives you if you insist on staying alive long enough to receive it.

The day of the final hearing in Reinbeck, the courthouse clock did not care how dramatic my life felt. It ticked with the same bored dignity it lends to parking tickets and property lines. Our lawyers stood like chess pieces who knew their moves long before the pawns ever did. Thomas’s attorney cleared his throat and produced the deed that had once made me nauseous from rage. He recited the words as if they belonged to a truth older than marriage: the apartment was never ours. It belongs to his mother. She may reclaim it at will. You have thirty days.

I thought of a narrow kitchen where I taught a toddler to stir batter by counting to ten. I thought of winter boots lined up by a door we could never afford to replace. I thought of a boy asleep on a couch I had paid for in installments so small you would mistake them for errors.

I smiled.

Not cruelly. Not even triumphantly. I smiled because the man across from me had no idea who I had become in the twenty years he hadn’t bothered to look. He didn’t know about the café with the woman who gave me a will and a benediction; he didn’t know about the boy who knelt in my kitchen and called me mother with more accuracy than a blood test. He didn’t know the sea could teach a woman her name again at fifty.

I smiled because I had been poor and housed and frightened and brave and wrong and right and quiet and loud and, finally, free. I smiled because this moment—his lawyer puncturing the air with a period he thought would end me—was, in fact, a comma in a sentence I’d already rewritten.

The judge asked if I had anything to add. “No, Your Honor,” I said. I wanted to tell him I had a plane to catch, a herb garden to water, a granddaughter who thinks my voice is embedded in lullabies, a man who looks at my scars and sees maps. But the courtroom is no place for poetry. So I slipped that smile into my bag with my pen and my checkbook and walked out.

On the courthouse steps, the Hudson Valley light was indecently beautiful. The air smelled like histories I didn’t have to carry anymore. I pressed my palm to my chest and felt nothing pounding there except a good, ordinary heart.

We live now in a villa that insists on doors open. Michael works late into the afternoon, his genius of focus broken only by his daughter’s insistence that the sea is more interesting than his data set. Emily moves through our kitchen humming songs I don’t recognize and love anyway. Sometimes I look up and find Samuel watching us from the terrace, a softness in his mouth that makes me feel like I am being read aloud gently.

At night, when the cicadas practice their opera and the sky dyes everything navy, I sit with the notebook Edward finally found the courage to give me: Isabelle’s. My mother’s handwriting slants, then stumbles, then stops mid-sentence in a way that makes me want to kiss the page. She wrote about violets and hunger and a song she could not get out of her head and the shape of a future she never got to hold. I run my fingers over the ink and speak into the dark.

“I found you,” I tell her. “And I found me.”

Sometimes the sea answers. Mostly, it’s my granddaughter—Anya—who wriggles from her bed and pads down the hall, hair a mess of moonlight. “Grandma,” she whispers, breath warm against my wrist. “Don’t leave.”

“I’m not going anywhere,” I say, and this time I hear myself and believe me.

If you’re hungry for the courtroom flourish, take it with you. If you’re looking for the moment I sank a blade into a man’s ego, enjoy it as a parable about signatures and hubris. But remember the part that matters: the secret I kept for twenty years was not a weapon. It was a child, a choice, a grief, a love. It was the reason I could sit across from a man who never really knew me and smile.

Because he never saw what I had survived. He never knew who I had become when he wasn’t looking. He never understood that a woman who has carried a silence that long knows how to set it down.

On the days when the villa fills with guests and roast chicken and half-understood conversations in three languages, I step back and watch, quiet in the doorway, the way you do when the good scene finally lands on stage. Michael lifts Anya high and she squeals and Emily throws her head back laughing and Samuel squeezes my hand under the table as if to anchor me in a place I no longer fear to leave.

I think of the girl in the ward with the humming light and the cold bassinet and the impossible offer. I think of the young wife who mistook endurance for devotion and the middle-aged woman who learned that a deed is not a home. I think of the grandmother who will teach a little girl to plant thyme and to conjugate to be in every tense that matters: I am. You are. We were. We will be.

Sometimes I reach for the old pendant I still wear out of habit more than need. It is not a talisman; it is a breadcrumb. It led me through a forest I thought I would die in and out the other side.

If you ever find yourself in a courtroom being told your life is smaller than it is, remember me. Sit up. Smooth your dress. Let your mouth curve the way you taught it to curve when men thought they were narrating your story. And then, from a place they cannot subpoena, let the smallest, truest smile unspool.

The secret of your strength is not the secret you kept. It is that you kept going.

END!

News

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

“She’s Alive,” I Whispered When I Saw the Photo of the Tycoon’s Deceased Daughter—But Why… ch2

“She’s Alive,” I Whispered When I Saw the Photo of the Tycoon’s Deceased Daughter—But Why… Part One The July…

Mother-In-Law Threw Away My Late Mom’s Jewelry Laughing So I Taught Her a Lesson She’ll Never Forget. CH2

Mother-In-Law Threw Away My Late Mom’s Jewelry Laughing So I Taught Her a Lesson She’ll Never Forget Part One I…

“I Have a Surprise for You Too,” I Smiled. My Husband Stepped Into the Hallway, Stunned, and Then… ch2

“I Have a Surprise for You Too,” I Smiled. My Husband Stepped Into the Hallway, Stunned, and Then… Part One…

My Mother Died Giving Birth to Me, A Midwife Took Me In—But Years Later, A Letter Exposed The Secret. ch2

My Mother Died Giving Birth to Me, A Midwife Took Me In—But Years Later, A Letter Exposed The Secret Part…

When I Got Married, I Never Thought My Husband Was Hiding Another Face—But That Night… ch2

When I Got Married, I Never Thought My Husband Was Hiding Another Face—But That Night… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load