I Went to the Bank for My Inheritance, the Clerk Mocked Me—Until the Safe Was Opened…

Part One

I remember the bite of Denver air in my lungs and the way the bank’s columns made me feel like a trespasser climbing steps to a stage where I hadn’t been cast. The gold-leaf logo in the glass door gleamed like a dare. I checked my reflection—frayed coat hem, salt-stained shoes, a little too pale—and nearly turned back. The key in my purse dug into my palm like an answer. I pushed through.

The lobby smelled like polish and money. Floors that wanted to see their faces in your shoes, counters lined with brass pens on leashes, a murmur of voices trained to stay low. The security guard at the door—broad-shouldered, squared jaw, E. REYNOLDS on his badge—watched me with that wary, not-quite-unfriendly look that says are you lost?

“Excuse me,” I said, trying not to let my voice tremble. “Could you show me the way to the safe deposit boxes?”

If I’d been a different kind of person, I would have enjoyed his double-take. He stood a little straighter. “You’ll need the branch manager,” he said, then added with a softening I hadn’t expected, “I’ll take you.”

He knocked on a heavy oak door. Inside, a man perched behind a desk big enough to hold a small conference. The name plate gleamed CHARLES WHITAKER, and his tie knot had been coaxed into precision. His smile didn’t reach his eyes.

“Yes?” Mockery lived in that single syllable.

“I need access to safe deposit box twelve,” I said. “My name is Olivia Parker. This is the key.”

The brass looked ordinary in my fingers. The way Charles leaned forward to stare at it made the room feel small.

“Box twelve,” he repeated, like he was tasting something familiar. “Odd. I don’t recall—well. Let’s see what we can do.”

He led me and the guard, Ethan, through heavy door after heavy door, each breath of the vault cooler and quieter, the air changing the way chapels do in winter. Steel drawers marched down the walls in bright ranks. Charles stopped in front of 12.

“This one hasn’t been touched in years,” he said, fingers grazing the engraved digits. He looked at me like he was trying to fit a puzzle piece that had fallen from a different box. “The key.”

I slid brass into steel. For a heartbeat, nothing. Then a click, soft as a sigh, and the door eased open. Inside lay a single object—an old carved box, dark wood polished by hands I knew too well. My mother’s hands. The patterns cut into its lid were both familiar and foreign: loops of vines, a crest I didn’t recognize, a tiny inlaid star.

“Go on,” Charles said, too close, breath smelling of expensive cologne and hunger.

I lifted the lid.

Light spilled over gold. It wasn’t the garish victory of a pirate’s chest; it was the quiet shock of rings and bracelets and necklaces tangled together like a sleeping constellation. A handful of stones winked—emerald, sapphire, one fire-bright round I wouldn’t let myself name. At the bottom, beneath the tumble of metal, a folded paper waited.

All those nights my mother and I counted coins at a kitchen table under a burnt-out bulb came back at once—the thin envelopes, the cut-off notices, the way she smiled around hunger. My throat closed. I pressed the lid shut.

“I’ll be going now,” I managed.

“Of course,” Charles said with a pleasantness that rang hollow. His eyes had not left the box. “Reynolds will escort you. It would be unwise to leave with valuables alone.”

The vault door shut on a whisper. The lobby swallowed us again—brass, marble, voices that knew better than to be loud. Ethan fell into step quietly, half a pace behind, professional to the bone.

“That was unexpected,” he said as we crossed the echo of the floor. Curiosity, not cruelty, edged the words. “You don’t look like someone who would have a box in a place like this.”

I laughed, no humor in it. “I don’t look like someone who has anything worth protecting, do I?”

He didn’t answer, and somehow the silence felt like respect. In the car, my voice found itself. “My mother was a custodian,” I said. “Her hands never healed from bleach. She worked nights. We lived off the rhythm of the clock in other people’s buildings. She never talked about my father. She never talked about anything before me. The only time she mentioned the future was three days before she died. She held my hand and said, ‘You’ll receive a gift that will carry you through everything.’”

I stared at my lap where the old wooden box sat, heavy, familiar, a stranger. “I thought she meant strength. I didn’t know she meant this.”

Ethan nodded once, a soldier’s acknowledgment. When he left me at my apartment, he didn’t say anything else. The hallway door shut on the scent of winter and bank-polish. The world went quiet around the box and me.

I didn’t open the note that night. Not at first. I watched the light move across the lid. I let the day catch up to me. And then, because I could not survive another minute of not knowing, I lifted the lid again, pushed the cool weight of gold aside, and eased the paper out.

The handwriting sloped the way my mother’s mouth had when she was trying not to cry. There wasn’t much—an address in Aspen, a phone number, and a small line, careful, urgent: You can always turn to them.

Them. Who? Why had we suffered ramen winters and candles-for-electricity nights if there had been a them? Anger spiked, swift and clean. Love followed it, messy and brimming, because grief makes a soup of your insides and leaves you to drink it.

That was when the lock on my front door whispered wrong. A sound too thin, too slow. The knob jostled, the deadbolt shivered. I did not plan. My body moved without asking me. I scooped up the box and backed away.

The door erupted inward on its hinges. Two men slid through—efficient, blank-eyed, one with a grin that didn’t know how to stop. He grabbed my arm; the wood dug into my ribs; I screamed his name without knowing it: Ethan—

—and then he was there, the bank guard without brass or marble, breath like a winter run, shoulder set. The room devolved into fists and glass and a sound I can still hear when sleep won’t oblige—the thundercrack of a pistol in a small room. Ethan staggered and set his jaw at the same time. He fought with training and something messier that looked like anger in the right places. Sirens swelled, the hallway filled with red-blue, and the men with blank eyes wore bracelets they hadn’t asked for.

When the door shut behind the police, my apartment looked like it had fought a storm. I pressed both hands to Ethan’s shoulder and tried to remember every emergency angle from a nursing textbook I hadn’t seen in years.

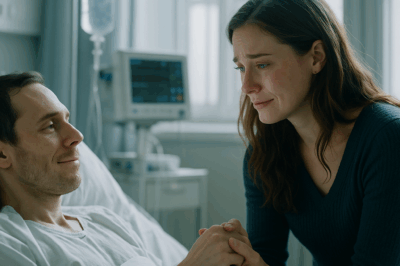

“Better me than you,” he said through teeth and breath.

And that was when the shape of my new life began.

He told me later, pale under hospital lights, that he had gone back after he dropped me off at home. He had knocked on the bank manager’s door and paused—he didn’t know why—when he heard the phone voice inside. Charles Whitaker said the words that made Ethan a different kind of employee immediately: I have the address. Tonight. A wooden box full of jewelry…

Ethan did not say the part out loud that I saw later in the shape of his mouth when he slept sitting up: he had disobeyed orders once before in a different uniform and lived to keep doing it. He said, “I told him my stomach hurt. I left. I ran.”

I called the Aspen number the morning after the police swept glass into plastic bins and left me with a hole where a door should be. An old man’s voice said hello and a woman’s voice said my mother’s name like a prayer. The bus to the mountains felt like time travel. Denver’s grit gave way to evergreen and the long thin line of blue that pretended it wasn’t sky but miracle.

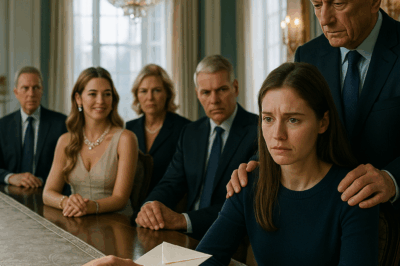

The Caldwell estate’s gate wore a crest like the one on the box. I pressed the intercom and thought my heart might not forgive me if it had to wait another second. The gates opened. The walk up the drive was long enough for seven different lives to happen and end. An older man and woman met me at the door. They had the kind of careful posture people learn not to display in pictures anymore. Their eyes, though, did the opposite of careful.

“Anna?” the woman asked, and then she reached for my face as if she couldn’t trust her hands to touch anything without it disappearing. “Oh, Henry, she’s back.”

“My name is Olivia,” I whispered. “Anna was my mother.”

Snow fell in my chest. Their grief was twenty years old and fresh as a bruise. I learned the story in front of a fireplace that had met presidents and watched toddlers take their first steps. Anna Caldwell, only child, a hurricane in a girl’s dress. She fell in love with a man who had a talent for leaving; she fell out of grace with a family who had a talent for pride. She carried me anyway. She left anyway. The Caldwells searched, fought with lawyers and each other, paid private investigators and private prayers. And then the news came—not of me, but of absence. A rumor of death. They buried the rumor in a coffin that held air and didn’t know whether to be relieved or ashamed.

“Forgive us,” Margaret said to my mother’s name carved on a stone later that night, snow climbing the letters. “We chose being right over being kind.”

“You knew where to send me,” I said softly, the paper in my pocket warm from my hand. “She wanted me to find you after she was gone. I think she wanted me to know both truths: that love can hurt you and that family can heal you.”

They insisted I stay. They insisted I eat. They insisted I sleep in a bed my mother had slept in as a child. I floated through the halls like a ghost who keeps checking the mirror and seeing someone she knows but can’t quite name.

Then I went to the hospital to sit with the man who had taken a bullet meant for me.

Ethan’s shoulder healed slowly and stubbornly. He hated the sling; the sling did not love him either. We walked the hospital garden when the weather allowed, and he explained four different ways to escape a room and which one was least likely to break anything you couldn’t replace. He talked about nothing and everything the way men do when they have learned it is sometimes braver to ask questions than to hold eye contact. His parents showed up with casseroles and stories and the soft proud look people give the world when the world has given them back their son. When his boss called, it wasn’t to ask for keys. It was to offer a promotion.

The bank lost a manager to handcuffs and headlines. The newspapers were full of a different last name, but Charles Whitaker’s arrest tucked itself onto page three and did not leave. He had been sloppy, greedy, recorded. The men with blank eyes had very good microphones and very poor loyalty. He pled; he went; he wrote letters to a son he had not seen in twelve years. I did not read them. I didn’t need to.

I went back to the Caldwells for a week and learned what home can mean after you have convinced yourself the word is for other people. Margaret taught me how to stand at a window with a cup of tea and let sadness arrive and leave like weather. Henry showed me the ledger books Anna’s grandfather had balanced with a fountain pen and a sense of humor you could see in the loops of his Gs. We didn’t talk about money much, which is how you know people have it. We talked about my mother’s laugh. We made our guilt form sentences and then let the sentences have their way with us.

I took a job at a small publishing house in Denver that smelled like dust and possibility. I learned to love commas and authors in equal measure. I saved money in a jar and called the jar Future. Ethan became director of security and learned to sit at a table and speak like a man who had earned chairs listening to him. We learned how to be a couple that didn’t need calamity to feel alive. When he asked me under cottonwoods in the Caldwell garden if I wanted to share names and mortgages, I said yes without thinking about the worst-case scenario first. The day we married, Margaret cried like a woman who had just been told grief could end. Henry shook Ethan’s hand hard enough to bruise and whispered something that made Ethan straighten like he was still standing at attention.

A year later we sat in a waiting room holding hands that had a little more confidence in them and listened to a doctor say the word pregnant with a smile that felt like sunlight. The Caldwell estate has many rooms, and one of them turned itself into a nursery with the speed and generosity of grandparents with second chances. I kept the old wooden box on the mantle for a while and then tucked it into a chest with other things I do not need to look at every day to believe they exist.

On a cold evening, when the mountains were paper-cuts against a navy sky, I took the note out and read it a last time. You can always turn to them. I had. The them had widened to include more than Anna could have predicted: a soldier with good timing; a banker with bad morals who had been dealt with; a couple in a stone house learning to be softer than they had been taught; a child who kicked against my palm and insisted there was a future whether or not I was ready.

When I went back to Denver to stand in a courtroom and watch Charles Whitaker stand to hear his sentence, Charles wore his same tie knot and a face that looked like it had been practicing regret and hadn’t nailed it yet. The judge read, the lawyers wrote, the spectators breathed. The clerk with the kind eyes stamped papers and did not smirk. When we stepped into the hallway, Ethan took my hand and squeezed. The weight I had carried up marble steps months ago fell away in increments you could measure like heartbeats.

Outside, the air was thin and righteous. It tasted like snow and something sweeter that I realized was happiness not needing to be loud. I thought of the first time I had stood in front of the bank, the security guard’s wary gaze, the manager’s practiced smirk, the humiliation trying on my coat to see if it fit. Then I thought of a safe door opening and light finding gold and a life stitching itself together with hands from both sides of the past.

Part Two

A funny thing about inheritance: the world assumes it is silver and stone and money in old boxes. Sometimes it is a story kept quiet long enough to be a secret and then long enough to be a sin. Sometimes it is courage you didn’t know you were trained to use.

Margaret says I am my mother’s girl in the way that counts and the way that the world equates with trouble—stubborn, forgiving in the wrong places until she learns not to be, and then generous past what the situation deserves. Henry says I am a Caldwell in the way that counts less and matters more—ledger-minded, eyes for the details that save you or sink you, a fondness for breakfast at windows. Ethan says I am myself, and he says it like a promise.

The first winter after everything, I graduated on a stage that felt like a joke because I was older than the girls in heels too high and younger than the adjuncts in blazers too elbow-patched. Henry and Margaret clapped before my name was finished, the kind of proud that steals a little air from the lungs of the people sitting behind them. After the ceremony, a girl in line at the coat rack tugged my sleeve and whispered, “My mom cleaned houses. She thinks she isn’t allowed to hope. Could you—” and she held out a piece of paper. A number, a name, a plea compressed into the formalities the world allows. I said yes to coffee. I always do.

The bank invited me to a “client appreciation gala” a year later when they cleaned house so thoroughly the smell of bleach hit each floor like a sermon. I stood by a table of canapés someone had tortured into swans and watched a man in a new suit mispronounce “compliance.” Ethan caught my eye and shook his head like we were both trying not to laugh in church. The new manager asked if I would consider joining a community advisory board. The answer would have been no in another lifetime. In this one, I said I’d think about it. People can learn. Institutions, too, if they are taught with patience and consequences.

Sometimes at night, after we put our daughter down and the house clicks into its soft noises, I sit with the old box again. I do not need the jewelry. Margaret insisted I keep it “as a corrective for every night you went to bed hungry.” I wear the simplest ring sometimes, a delicate band with an engraving so worn you can only tell it used to be words if you want badly enough to read them. The rest stays put, a museum of choices a young woman made when she was told she had none.

I called the Aspen number printed on the note one last time in spring to ask a question that had finally let me see it needed asking: why hadn’t they found her? Why hadn’t they pushed past their pride when it hardened and done something monstrous in its kindness like show up at a diner where she worked and make a scene so loud love would have had to be admitted? Henry listened until I was done. “Because we were cowards,” he said. “And because the world told us wealth meant we didn’t have to beg. We learned too late that sometimes begging is the bravest thing.”

There are days when the mountain light pours over the Caldwell staircase like it has plans for us. I watch our daughter crawl toward it, fists flattening and releasing against the wood, her laugh bouncing off portraits that have seen a hundred versions of joy and are learning a different one. I think of Anna, barefoot in a dormitory hallway, telling a boy she loved him even though the cards were already telling her they would not be kind. I think of Ethan, bleeding in my living room and smiling through it because some people learn early that kindness is just courage in civilian clothes. I think of me at a front door that gave way and a voice that said my name with relief and command both attached.

I am writing this on the anniversary of the day I watched a safe door swing open. The clerk at the bank did not know he was teaching me a lesson when he let his face betray his contempt. He did not know I would carry his expression the way other people carry wedding vows or lullabies. He did not know he was the beginning of the story I tell other women when they whisper “I don’t belong here.” I tell them the truth that saved me again and again: keys don’t ask what you’re wearing.

We had a small christening for our daughter in the church where Margaret was baptized. Soft lilacs and a minister with a laugh like a creek in summer. We put the rattle from the old box in our little girl’s hand, and she swung it hard enough to make everyone laugh. “That’ll do,” Henry said softly, and his voice had the shake in it that makes your own eyes hot. After, in the kitchen that had seen three generations ruin recipes and perfect others, Margaret poured coffee and told me a story about Anna stealing a loaf of bread from the pantry as a child because she thought crumbs were “boring” and the heel was where the flavor lived. I didn’t know you could love a person you’d never had a conversation with this much. Turns out you can.

When I go back to Denver, I walk past the apartment where the door used to rattle wrong and where Ethan bled. It has a new door and a new paint color now. I want to tell the girl inside to keep a chair wedged under the knob when her heart says it needs one even if the world says she’s dramatic. I want to tell her she hasn’t met the people who will fight for her yet. I want to tell her she will.

I make a habit of leaving keys in the pockets of coats I donate. I leave a note sometimes, too, in a cramped hand that looks like my mother’s when I rush. You can always turn to them. I don’t define them. It’s better that way. Let the line widen around whoever proves themselves worthy.

The day Charles Whitaker stood in court for sentencing, the clerk who mocked me the first day was not there—he had taken a job across town. The new one smiled at me like I belonged and slid me a pen without a leash. It is a small thing, the difference between derision and decency. It changes the flavor of your day anyway. When the judge spoke, Charles stared at a middle distance that didn’t include me. I didn’t need it to. The safe had been opened. So had I. Neither of us were what we had been before.

On the drive back to Aspen, our daughter slept with her mouth open the way babies do when they intend to trust you completely. Ethan hummed without knowing he was doing it. The highway unspooled like a promise someone kept after all. Snow still clung to north faces; aspens made lace out of the sky. Road signs ticked off miles we would no longer measure in hunger or fear.

“Do you ever think about that day?” Ethan asked softly, careful not to name it in case naming it called it back.

“All the time,” I said. “But it lives in a room with the door open, not one we’re locked inside.”

He reached across the console and found my hand. His palm was warm and a little rough from the way he insists on fixing things himself. I squeezed, the way you do when you want to say we made it without making too much noise about it.

We pulled into the drive. Margaret waved from the porch like a painting learning to move. Henry opened the door before we knocked. The house smelled like rosemary and something baking too long the way things do when you get distracted by happiness.

After dinner, I pulled the old wooden box down and placed it on the table. We opened it together: Margaret, Henry, me, Ethan, and the baby—who tried to eat a necklace because this is the job of babies. The jewelry shone. The paper lay where it always had, creased and tender. I slipped it into the lining of the lid, permanent now where it had always been temporary.

“Keep it,” Margaret said, her hand on mine. “Not because it’s worth money, though it is. Because it’s the proof that love sometimes looks like leaving and sometimes looks like telling someone where to find home.”

If the clerk from the bank had walked past the window then and looked in, he would not have recognized the woman laughing with her grandparents and a soldier and a child who shook a rattle like a battle cry. He would have thought he’d taken a wrong turn and arrived at a different story. He would not have known it was the same one.

We are not the sum of the rooms that tried to keep us out. We are the keys that turned anyway. And when the safe was opened and the clerk’s smirk died on his face, it wasn’t because gold glinted. It was because a woman who had been told all her life she didn’t belong had kept coming back until the door said yes.

That is the inheritance my mother left me. Not jewels. Not even the family I found because of them. The audacity to walk into places where derision waits on polished shoes and say with a steady voice, “Number twelve, please,” and stand there until the lock remembers what it was made for.

END!

News

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… CH2

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… Part One The dog trembled in…

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… CH2

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… Part One It…

Rushing to My Fiancé’s Mansion, I Defended a Helpless Stranger… and What I Discovered Shocked Me. CH2

Rushing to My Fiancé’s Mansion, I Defended a Helpless Stranger… and What I Discovered Shocked Me Part One I didn’t…

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off. CH2

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off Part…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me……

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything. CH2

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load