I Was Shattered When I Found My Grandma Locked In The Basement While My Family Danced Upstairs…

Part One

My name is Sarah Mitchell, and on New Year’s Eve I kicked open the basement door of my father’s house in Charleston, West Virginia, and found my grandmother locked inside and crying. Upstairs, music rattled the windows, champagne corks popped, and my family danced like nothing was wrong.

I didn’t say anything at first. I didn’t have to. I scooped Grandma Ruth into my arms, felt every fragile bone through her thin nightgown, and carried her up the narrow stairs into the center of the party. The room froze. In that split heartbeat, the speakers were still hissing, a string of sequined streamers drifted like jellyfish in the stale air, and someone’s laughter died mid-breath.

I set Grandma gently on the couch. Her knuckles were mottled and cold; faint bruises ringed her wrists where someone had “guided” her too hard. I took my badge from my pocket, the gold catching the ceiling light, and laid it on the coffee table where every eye could see it.

“It. Ends. Tonight.”

Linda, my cousin with the heavy eyeliner and heavier opinions, tried to fill the quiet. “You’re overreacting, Sarah,” she said, voice tight around the rim. “It was quieter for her downstairs. She wanted to rest.”

“Is that what you told yourself,” I asked, “so you could keep dancing while she cried?”

Linda’s smile went paper-thin. Her brother Mark took a breath like he was about to laugh and then thought better of it. “Don’t be so dramatic,” he muttered. “It’s just a lock.”

I looked down at Grandma’s hands, at the tremor working through them, at the way they curled like she was bracing for the next command. “Fine?” I said to nobody in particular. “Does this look fine to you?”

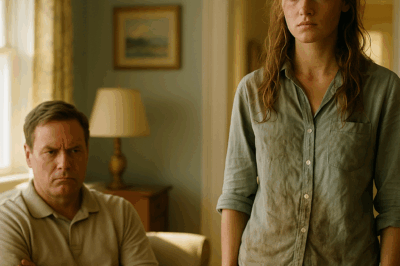

On the mantle, Frank Mitchell, Sr.—my father—set his glass down too carefully. Years in the mines had carved lines into his face that even retirement couldn’t sand away. He didn’t step forward. He didn’t kneel. He stared at me from the shadowed edge of the room.

“You’ve been gone a long time, Sarah,” he said. “You don’t know what goes on here anymore.”

“I know enough,” I said. “I know she doesn’t belong in a basement.”

For a second I thought he’d explode, the old temper rising like a furnace off-balance. Instead he grabbed his coat, went through the kitchen, and let the screen door slap behind him. The music died altogether. People started remembering babysitters and early shifts. Champagne flutes were left sweating on end tables. By midnight, only Linda and Mark remained, whispering in a corner like kids caught shoplifting.

I tucked a blanket around Grandma’s shoulders and sat close enough for her to lean against me. The old house exhaled—the way it always had after my father left a room. Somewhere in the back of my head, the sound of my childhood returned: the kitchen clock ticking louder when I couldn’t sleep, Grandma’s slippers padding across linoleum, the screen door’s slap marking the cadence of our days. My mother left when I was little. Grandma filled the space without asking for applause.

It was Grandma who gave me my first flashlight so I wouldn’t be scared of the dark. Grandma who kept the clipping when I made the local paper for the academy. Grandma who told me, the day I pinned my badge: People will doubt you, especially because you’re a woman in uniform. Don’t let them take your dignity. That’s the one thing you can never give away.

I brushed a strand of hair from her forehead. “I’m here now, Grandma,” I whispered. “I won’t let them hurt you again.”

Her eyes fluttered open—clouded, but clear at their center. “I knew you’d come,” she murmured.

“I should’ve come sooner.”

Her fingers found mine with a surprising strength. “Don’t blame yourself,” she said. “You’re here when it matters.”

Morning arrived gray and damp, the kind of January that hangs so low you could brush the sky with your knuckles. I fried bacon, because bacon is what home smells like in West Virginia when you’re trying to stitch an unraveled night back together. Grandma hummed an old hymn at the kitchen table, wrapped in her blue shawl, her hands cupped around coffee like a sacrament.

“They keep my checkbook,” she said softly. “Say it’s easier that way. They tell me I’m forgetful. They… they don’t want me around when people visit.”

“You’re not a burden,” I said. I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to. “Don’t you ever believe that.”

She nodded once. “I only believe what I see. And what I see is you, here.”

After breakfast I walked the property. Three acres at the edge of town—enough to pretend we had space, not enough to muffle a slammed door or a shouted word. The coal shed leaned like a retired soldier. The barn roof sagged under memory and weather. I could still see child-me tearing across the yard, Grandma cheering, Dad barking about “wasting time.” When I circled back, Mark’s pickup growled up the drive.

“You planning to stay long?” he asked, flicking ash into the slush. He wanted me to flinch. I didn’t.

“As long as Grandma needs me.”

“That old woman’s tougher than she looks,” he said. “She don’t need babysitting. You, though—” he gestured toward my hip “—you roll in with your badge like you own the place. Don’t forget whose name is on the mailbox.”

“You locked her in a basement,” I said. “You and Linda. You think I don’t know?”

He smirked. “You don’t know half of it.” The smirk faltered under his own words. He killed the cigarette, climbed into the truck, and spit gravel down the drive.

That night the fire snapped and hissed like it had opinions about our day. Grandma dozed in her chair, lashes fluttering with dreams. I thought about the night Dad almost pulled me out of school at twelve to scrub the house while he worked doubles. Grandma, hands on hips, had strode into his room and said, “Frank, if you steal that girl’s future, you’ll answer to me.” He’d glared. He’d grumbled. He’d backed down.

When I graduated the academy and he didn’t show, she’d stood in her Sunday best on the far side of the parade ground and waved like I was the only one who mattered. Afterward, she’d pressed a folded twenty into my palm—money she didn’t have to spare—and said, “For your first badge polish.”

There are debts you can’t repay with paper. There are debts you repay with presence. I had stayed away for twenty years and told myself the distance was wisdom. Maybe I was the only one who could fix this, not because I wore a badge, but because she had earned someone to carry her dignity through a room where people had forgotten what it looked like.

Two days later I drove her downtown to Harper & Sons on Capitol Street, the law office above the hardware store that still sells nails by the pound. The place smelled like coffee and floor wax. The gold leaf on the door flaked when you looked too hard at it. We climbed the stairs slow. Folks in the waiting room snapped their heads up like they’d been caught listening through the wall.

Linda wore fur trim and outrage. Mark had a belt buckle big enough to stop a small-caliber round. My father stood by the window with his arms folded like steel cable. A woman about my age appeared from the inner office with a steady gaze and a hand already reaching. “Eleanor Price,” she said. “Mrs. Mitchell. Officer Mitchell. Come on back.”

The conference room fluorescents hummed above a long oak table carved and scarred by years of elbows. Eleanor clicked her pen, smoothed a stack of papers, and looked my grandmother full in the face. “We’re here for the reading of Ruth Mitchell’s last will and testament,” she said. “Mrs. Mitchell, are you comfortable?”

Grandma nodded. “I’m fine, dear.” Her voice had the soft rasp of a woman who has read scripture and recipes and bedtime stories out loud for seventy years.

Eleanor started with the small things that are, in fact, never small: my grandmother’s wedding band to me, her cedar hope chest to Jeanie in Ohio, a box of recipe cards to Aunt Melissa, who couldn’t be bothered to come. Linda flipped through a pile of handwritten notes assigning quilts to neighbors and grunted like kindness cost too much.

“As for bank accounts,” Eleanor said, “the savings and the CD at Kanawha Valley Bank will be combined for the beneficiary designated in Section Four.”

Linda sat up straighter. “Section what?”

Eleanor cracked the blue tape on a manila folder and drew out a single typed sheet topped with Ruth’s looping signature. The room stilled—coat sleeves whispering, the clock thunking time forward one second at a time.

“Section Four,” Eleanor read. “I, Ruth Mitchell, of sound mind, do hereby bequeath my primary residence at 214 Maplerun Road, all furnishings therein, the remaining balances of my accounts at Kanawha Valley Bank, and the deed and mineral rights attached to the parcel known as Mitchell Hollow, Elk District, Kanawha County, to my granddaughter, Sarah Mitchell.”

Silence rolled across the table and broke like a slow wave.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Mark said, half-rising, palms pressed flat to the wood. “To her? She ain’t been here. We did the work. We took care of you.”

My father didn’t sit. He didn’t blink. “Ruth,” he said—my grandmother’s name a warning, a plea, a habit—“tell them this is a mistake.”

Grandma lifted her chin. Small. Steady. “I meant every word.”

“This is theft,” Linda snapped. “That acreage is worth real money. We were counting on the house.”

“You’ll want to watch your language,” Eleanor said, not looking at her.

“It’s Mitchell,” Linda said, as if a name could save her. “And I’m not watching anything. This is a setup. Sarah shows up, plays hero, and suddenly everything’s hers.”

“Grandma made updates months ago,” I said. “Before New Year’s Eve. Before I came home.”

“You brainwashed her,” Mark jabbed a finger at me. “Always were her favorite. She fed you those letters, those clippings, made you a saint in uniform. What about the rest of us?”

“The rest of you locked me in a basement,” Grandma said.

The room went so quiet we all heard the fluorescent hum admit it had been there the whole time. My father turned toward her, something ugly crossing his face and leaving a map of itself. “You wander,” he said. “You fall. We did what we had to. Sarah’s always judged us from somewhere else.”

“I understand perfectly,” I said. “I understand bruises on wrists and a padlock on a door. I understand that music upstairs is not a reason for darkness downstairs.”

Eleanor tapped the papers square. “The will stands unless successfully contested in court. If you intend to challenge, we can schedule mediation first.”

“Damn right we’ll challenge,” Linda said, snatching her purse. “Undue influence. Lack of capacity.”

“Mrs. Mitchell passed a cognitive assessment in May,” Eleanor said. “Physicians’ letters are on file.”

Mark’s mouth opened and closed like a startled fish. My father stared through the window at a gray day that refused to cooperate with his narrative. For a second I thought he might meet my eyes. He didn’t.

We bundled Grandma into her coat. On the sidewalk, the air smelled like thawing snow and river. “You did fine,” she said.

“We’re not done,” I said.

“No,” she agreed. “But we’ve started.”

People love to talk about justice like it’s a lightning strike—clean, dramatic, inevitable. Most of the time it’s slower. It shows up with a binder and a docket number, with neighbors sitting on hard benches because they remember who taught their kids to read.

The hearing room was beige and square and familiar to me in a hundred other cases, but this time the pews held old miners in ball caps, women from Grandma’s Bible study, a cashier from the Shop ’n Save who slipped a card into my hand and squeezed my fingers. Mark swaggered in with a slick lawyer and shiny shoes; Linda wore anger and fur trim. My father came in last, the set of his jaw making a lie of his steady steps.

Plaintiffs went first. A neighbor testified that Grandma had once left the stove on. The pharmacist said she mixed her pills twice in a month. Linda said “confused” so many times it lost its shape and just sounded mean. Mark talked like he was fixing something when he’d been the one to break it.

Eleanor stood and asked quiet questions: Did she recognize you? Did she pay bills? Did she attend church? The answers, under oath, sounded less like concern and more like the threadbare excuses they were.

Then Eleanor held up photos—ones I’d taken in the cold light of the kitchen the morning after New Year’s: bruised wrists, a padlock, a cot. The gallery murmured. Someone said “Lord have mercy” under their breath like a prayer they were ashamed of needing.

My turn. I swore and sat and let the truth do its work. “I came home unannounced. I heard music upstairs and crying downstairs. The door was locked. I broke it. She was cold and alone. That’s the truth.”

The plaintiff’s attorney tried for a smirk. “You’ve been absent for years, Officer Mitchell. Why swoop in now?”

“Because distance doesn’t excuse abuse,” I said. “Because nobody wants to be locked in a dark basement on New Year’s Eve while their family dances upstairs.”

The judge called Grandma. I wanted to carry her to the stand, but I let her walk with her cane because that’s how dignity travels when it insists on making its own way. She raised her hand. She told the truth in the voice that once taught half the holler to read.

“They say I was confused,” she told Judge Collier. “But I was never confused about one thing: who loved me and who didn’t. Sarah visited when she could. The rest locked me away. I may be old, but I know what dignity feels like and what it doesn’t.”

She pulled a folded paper from her shawl pocket—a copy of the letter she’d sent me in June—and asked Eleanor to read it. Sarah, you are my strength. Others may see me as a burden, but you have always honored me. I want you to have this home because in your hands it will remain a place of love, not shame. The room held its breath the way a congregation does when truth takes the lectern and refuses to blink.

Judge Collier looked at my grandmother, then at me, then at my father. “I’ve known Ruth Mitchell my whole life,” he said. “She taught my boy to read when he hated books like cusses. I don’t see a woman without her wits. I see a woman failed by those closest to her. The will is upheld. The estate passes in full to Sarah Mitchell. And I’ll add,” he said, gaze hard enough to spark, “locking away an elder is not care. It’s cruelty.”

The gavel cracked like thunder in a valley. Linda gasped. Mark cursed small and childish. My father’s hand whitened on the back of the bench. When I stood and offered Grandma my arm, neighbors rose in a ripple—miners, church ladies, a teenage cashier—nobody clapping, nobody making a scene, just standing because some respect wants your weight, not your noise.

We walked out into daylight, into a world that had decided to believe her.

Part Two

July heat settled on Charleston like a heavy quilt, but the whole town came out for the Fourth anyway. Kids shook sparklers into scribbles. The high school band wheezed “Stars and Stripes Forever” like an elderly dragon with good intentions. Veterans in ball caps lined the curb, swapping lies and sunscreen. I pushed Grandma’s chair to a spot under the maple near the VFW hall. When folks saw her, they straightened like string pulled from the blue.

“Good to see you out, Miss Ruth,” an old miner said, his voice soft around the vowels.

She lifted her hand, waved like she was shy of the attention and hungry for it at once.

Across the street, my father stood with his arms folded in that old and familiar architecture. He didn’t wave. He didn’t smile. He watched, a man who couldn’t figure out how the room had stopped listening to him and started listening to the one he’d always talked over.

The mayor tapped the mic and winced at the squeal. “Before we continue,” he said, “this town wants to honor one of its own. Ruth Mitchell taught generations of us to read. She did it with patience and a paddle for those of us who needed it.” The crowd laughed, and the mayor grinned. “She gave more to this community than we can count, and it’s time we said so.”

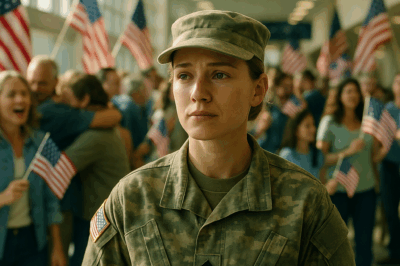

At his signal, a dozen veterans stepped forward and formed a line in front of us—women with silver hair in uniform skirts, men with shaking hands trying not to let the tremor show, a couple of younger ones still narrow-hipped in their dress blues. One by one, they raised their hands in salute. The crowd fell quiet enough that the flag could be heard snapping. Grandma’s hand trembled on my arm. She reached up and tapped my badge.

“Stand,” she whispered. “Salute with them.”

I did. For a heartbeat, time braided us into one thread—veterans, a grandmother, and a daughter with her palm at her brow. Across the street, my father finally dropped his eyes.

Back on Maplerun Road, the house looked different. Not magic different—porch steps still needed scraping, paint still peeled in strips like old wallpaper—but neighbor boys had hammered the worst boards into safe shape, and the church ladies had planted marigolds that weren’t pretty so much as stubborn. The place breathed people again.

We sat on the porch. The air smelled like far-off barbecue and fireworks powder. I told Grandma about plans that had gotten bigger when Eleanor told me the mineral rights meant more than a story told over coffee: a Ruth Mitchell Community Center in the old barn, a weekly supper where widows and vets and anyone whose family had made them small could come and not have to make a case for their hunger, a reading room with a paneled wall of hand-me-down books and a sign over the door that said NO QUIET REQUIRED in letters tall enough to see even with old eyes.

“I never wanted riches,” Grandma said. “I just wanted to leave something good behind.”

“You did,” I said. “I’m just putting your name on the door.”

We opened in September with crockpots plugged into a tangle and riggers tape holding cords where feet couldn’t trip. The church ladies claimed the kitchen like they’d been waiting. Wayne from the hardware store brought folding tables that bowed politely under casseroles. A boy with the start of a mustache stacked chairs and wouldn’t let anyone older touch them. Mark didn’t come. Linda didn’t come. My father stood once at the edge of the parking lot and turned away when a volunteer spotted him.

The first person through the line was a man I’d arrested once for disorderly conduct at the Bluebird Tavern. He looked at the sign, at me, at the steam rising from meatloaf, and managed, “You serious?”

“Dead,” I said. He grinned and took seconds.

We added a shelf of paperbacks with cracked spines and a sign that said TAKE. KEEP. SHARE. A girl in secondhand sneakers read a picture book to a cat that refused to leave once the door got held open too often. People learned each other’s names and each other’s stories without insisting on the parts that felt like getting undressed in public. There are places you are required to whisper; this wasn’t one of them.

In October, I found my father standing in the barn doorway when the supper was over and the lights were strung back to hooks. He held his hat like it required instructions. “I heard,” he said, then stopped.

“You heard what?” I asked, not unkind and not helpful.

“That you’re using my father’s name like an ornament,” he said finally. “Without my say.”

“Your father’s memory,” I said. “Your mother’s name. Your say has done enough.”

He nodded once, like a man who has run out of lies he believes. “You always were hard,” he said.

“No,” I said. “I finally got soft in the right direction.”

He didn’t come back. He didn’t stop me either. There’s a kind of repentance that is too fragile for the volume some people demand. I didn’t require it. I required absence, which he handled with excellence.

Winter settled early and cold. The community center steamed with soup and stories. The room smelled like yeast rolls and dignity. When a blizzard took out power for two days, we handed out blankets, checked on Miss Alma down the hill, and found the generator my father had bought ten years ago during a different storm with different courage and got it running for Mrs. James, who’s on oxygen. Nobody wrote a check. Nobody gave a speech. We put our backs into it and pushed.

In March, I sat at Grandma’s table with a calculator and an iced tea and a growing comprehension of mineral rights that made my head hurt. Eleanor showed me how to move the money quietly into a trust that would feed the center long after we were stories. “My grandmother would hate fuss,” I said. “Let’s build something too sturdy to require it.”

“Done,” she said, and clicked her pen. She’s the kind of lawyer who makes the law feel like a fence you asked for, not one built to keep you out.

I still wear a badge. I testify in beige rooms and stop cars for running reds and hold hands in alleys when the sirens have done everything they can and it isn’t enough. But now I go home to a porch where the light is on because I turned it on, not because I’m waiting to see if someone else will remember. Grandma sits in her chair by the window, shawl neat. Sometimes she forgets what day it is. She never forgets to say thank you to the boy who brings the mail.

On the anniversary of New Year’s Eve, I cooked black-eyed peas and cornbread and a pan of collards that made the house smell like history. Linda sent a card thick with perfume that said No hard feelings in loopy letters that refused to land on truth. Mark texted a photo of a new job badge. My father left a voicemail on a Tuesday afternoon: “I drove by the barn. Looks good.” I didn’t save it. I didn’t delete it. I let it sit in the space between anger and the kind of forgiveness that isn’t for other people so much as for the part of yourself that needs to put things down.

At midnight I stood in the doorway to the basement I’d kicked open a year earlier. We’d painted the walls. The padlock was gone. The bulb wasn’t a bare 60-watt anymore; it was a warm pendant that made the old concrete look like stone on purpose. I stood there with the memory and all the air I could hold and then turned the light off and shut the door gently. Upstairs, Grandma hummed. Outside, someone shot bottle rockets over the river and yelled happy new year to a street that still belongs to all of us.

Sometimes people ask me what changed the most. They want an answer that fits into a sentence you can fold and carry in a wallet. I tell them the truth: nothing and everything. The house still creaks. The friends who stood in the courtroom still hold us up. The ones who refused to see still look away. The center smells like rolls. The cat thinks she owns the reading chair. The marigolds survived the first frost.

Grandma taught me that dignity isn’t a trophy other people award. It’s a muscle you use when nobody claps. She carried it through rooms that tried to make her small. When I found her in the basement—cold, alone, hidden—I thought I was bringing her out of the dark. Turns out she had been lighting the way the whole time. All I did was hold the match high enough for other people to see.

So if you came here looking for a moral—if you found this because you typed how to stand up to family into your search bar at midnight when the house is too quiet—take this with you: the lock is never the last word. The party upstairs isn’t the whole town. The basement door kicks easier than you think when you decide. You are allowed to say It ends tonight and mean it, not because you have a badge, but because you have a name.

And if you ever have to carry someone up a flight of stairs and set them down gently in the center of a room that forgot them, know this: there are more of us than there are of them. The ones who will stand when a judge says the thing that should have been obvious. The ones who will bring soup and books and too much butter. The ones who will teach a girl to read under a maple tree and call that enough, then watch it bloom into a building with her name.

Justice, we learned, is not the fireworks. It’s the porch light, left on. It’s the bell over the door that rings when a woman with a shawl and a cane arrives and is greeted by name. It’s the way a community rises, quiet and unashamed, to make a wall of respect around the person who should have had it all along.

END!

News

At 1 A.M., My Mom Collapsed at My Door — Dad Hit Her for His Mistress. I Put On My Uniform… CH2

At 1 A.M., My Mom Collapsed at My Door — Dad Hit Her for His Mistress. I Put On My…

At the Will Reading, Dad Smirked With His Mistress – But Grandma’s Final Wishes Changed It All . CH2

At the Will Reading, Dad Smirked With His Mistress — But Grandma’s Final Wishes Changed It All Part One…

I Come Back From Afghanistan With One Arm — And My Family Acted Like I Didn’t Exist… CH2

I Come Back From Afghanistan With One Arm — And My Family Acted Like I Didn’t Exist… Part One…

My Dad Skipped My Iraq Homecoming. A Week Later, He Called in Panic. CH2

My Dad Skipped My Iraq Homecoming. A Week Later, He Called in Panic Part One “Your brother’s BBQ is…

My Dad Was Disappointed I Came Back Alive — So I Did What He Feared Most. CH2

My Dad Was Disappointed I Came Back Alive — So I Did What He Feared Most Part One I…

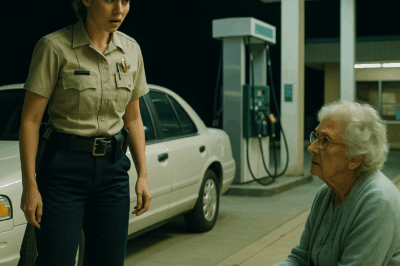

At 2 A.M. on Patrol, I Found Grandma Abandoned at a Gas Station. What Happened Next Shocked Everyone. CH2

At 2 A.M. on Patrol, I Found Grandma Abandoned at a Gas Station. What Happened Next Shocked Everyone Part…

End of content

No more pages to load