I was fired by the new CEO on his first day, the bouquet I brought still trembling in my hands. “Selene Ward, your time is over.” He didn’t know that two days earlier, I’d had a crucial meeting. The next morning, the secretary burst in, breathless: you need to see this…

Part 1

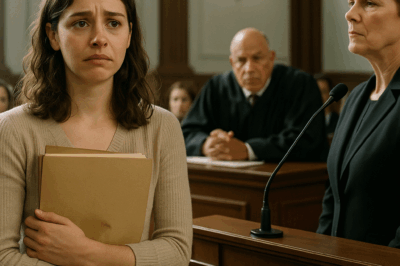

The bouquet trembled in my hands when he said it.

“Selene Ward, your time is over.”

No hesitation, no pause—just the clean execution of a man who’d practiced the line in a mirror until it felt inevitable. James Mercer stood in the doorway to the boardroom like a portrait—new CEO, ten years my junior, cufflinks that caught the light in tiny suns, and eyes so cocksure they might as well have been blindfolds. Behind him, a panorama of the city that my decisions had helped pay for: steel and amber, scaffolds and cranes, a skyline that didn’t know it had a new name at the top.

I didn’t argue. I didn’t plead. I placed the bouquet—lilies and small white roses—on the table to keep my hands from shaking and smiled because he had no idea.

Two days earlier I’d been in a closed-door meeting. Not with him, not with the full board. With the people who actually moved the strings: the partners, the shareholders, the ones who didn’t wear the company hoodie but kept a drawer full of them. We were in a quiet conference room at the Meridian Hotel, a place that understood discretion the way surgeons understand scalpels. Their breakfasts sweated in silver domes against white linen. My cup of black coffee had gone cold and remained perfect.

I had walked out of that room carrying more than a bouquet. I carried leverage.

The first time I met James had been three years prior, when he was a consultant with too much charm and too little restraint. He lingered near my door asking questions he already knew the answers to, testing me with that smile. Quick with decks, quicker with praise, he gravitated to power as if it were heat. I mistook his hunger for brilliance. I let him close. I even recommended him to the board when the headhunter sent a short list for “fresh leadership that could speak product to markets and markets to product.”

He used my own hands to sharpen the knife.

The first sign had come in a whisper—a meeting I used to run, rescheduled without me. Then a document I should have reviewed, already signed. His name began to appear in conversations that used to be mine like a watermark: inexorable, faint, permanent.

Then the email. I wasn’t meant to see it. A mis-forward from a junior analyst who thought my “SWard” address belonged to a different Ward in operations. The line was so unremarkable in its cruelty I had to read it twice to respect its audacity:

Selene is dated. She’s too tied to the old guard. If we want a future, we cut her loose.

It wasn’t the words that hurt. It was the tone. Casual. A scheduling note between lunch and a haircut. A woman reduced to a line-item on a slide titled “Impediments.” I archived the email. It did not delete itself. The grief that rose inside me put on a harder coat. I revised the plan I had been preparing in a quieter place in my head.

I wasn’t going to stop him.

I was going to let him destroy himself.

I began with the numbers, because numbers, unlike men in new suits, don’t change depending on who reads them.

Ward & Co. was stable—boring in the way that pays salaries. We grew 8–12% annually. We didn’t trend on Twitter. We made things that worked behind other things that won awards. James pitched the board on “unlocked upside.” He said the words leveraged expansion the way some men say I love you—not for the first time and never when it counted. He whispered accretive acquisitions to anyone who’d take a call; he spoke of “asset light partnerships” with companies whose liabilities were printed in newspapers large enough to wrap fish. He promised impossible growth and designed it to be impossible to disprove—until it wasn’t.

I let him sell it. Publicly I nodded when he spoke, because men like James do not see knives in smiles. Privately I gathered files. Every projection he stretched like dough. Every liability he buried in footnotes. Every executive he told, “When I’m in the chair, you’re my right hand.” I traced the web and watched how thin the threads were when you tugged gently on the corners.

James didn’t understand that the systems you inherit have manual overrides.

I visited the CFO, Dana—quiet as paper, sharp as paper cuts. We sat in her office like co-conspirators, the blinds whispering across sunlight.

“You see it too,” I said, sliding a folder across the table.

She opened the first tab. She inhaled once, the way divers do. “He’s amortizing fantasy,” she said evenly.

“Can you put it in a sentence a partner will understand?”

“With these assumptions,” she said, tapping two cells, “we will need to borrow to pay dividends within six quarters.”

“That’s not a sentence,” I said. “It’s a eulogy.”

She closed the folder and looked at me over steepled fingers. “What are you going to do?”

“What you trained me to,” I said. “Make the invisible visible. In a room that believes in light.”

I called the breakfast at the Meridian. Seven men and two women who controlled 34% of the voting shares between them. The few who had sat with William in the original garage, back when we used whiteboards like faith. I laid out facts, calm and controlled: the preliminary diligence everyone waved away as “high level,” the money we didn’t have yet already promised to advertisers, the deemphasized line items called customer success that meant support staff who would be cut and take their knowledge with them, the clause in a partner letter of intent that gave a private equity fund the right to swap our stock for theirs if we missed a target by a rounding error.

I didn’t demand anything. I asked them one question.

“Do you trust him with your money?”

The silence that followed was heavier than outrage. They glanced at one another, small, precise looks—the way people who do not have to raise their voices communicate verdicts. One of them, a woman with a half moon of scars on her wrist she didn’t bother to hide, closed her leather notebook and said, “We will speak to counsel.”

I left the hotel to the smell of bacon and fresh coffee and the particular sound carpeted floors make when men in expensive shoes cross them. I held the elevator button; it arrived. I thought of the bouquet on my kitchen counter—a silly indulgence I’d bought for myself because I had a tendency to mark beginnings and endings with flowers. I took them with me to work. I had no intention of letting them be about him.

Two days later, the bouquet trembled in my hands.

James said the line. The boardroom air didn’t stir. He set a white envelope on the table with the solemnity of a priest placing an icon.

“I’m not surprised,” I said.

“You should be grateful,” he said, smiling at the word. “We’ll take care of you.”

“I’m sure you will,” I said.

Sandra had sent me a text at dawn: Good luck today. Hats and knives. I tucked the flowers under my arm because hands that are full cannot wring themselves.

I walked out past the reception desk. Anna, the secretary who kept the place from tilting off its axis, looked up with eyes wide in a way I had last seen when someone said fire. She mouthed I’m sorry. I mouthed don’t be. Stupid, I know, but I liked the symmetry.

Derek from Product, who had worn sneakers to work before James crowned him VP of Innovation, had the good sense to widen his gaze when he saw my flowers. He shook his head. I nodded. We created a friendship out of that exchange, later.

“Selene—” James called after me, a stutter in his voice that sounded like wind mispronouncing its own name.

“Good luck, James,” I said without turning.

I didn’t watch him sit down at the head of the table where the chair still remembered William’s weight. I didn’t see him ask for water. I didn’t see him smile at the directors as if he were introducing a magician he’d paid for out of his own pocket. But I can recite what happened next, because Anna told me every detail so I could keep it like a jewel.

Ten minutes. He was mid-sentence, a slide titled Our New Era paused in the uncanny valley between confidence and delusion, when Anna burst into the boardroom. She never bursts. She enters. Respectfully. With competence. She stopped at the threshold and said, “I’m sorry, you need to see this.”

Her voice: breathless, steady, the way a person delivers bad news without making it performative.

She placed a tablet on the table and hit a button. The screen flashed to a financial outlet. Headlines scrolled like hail.

MERCER’S RISKY EXPANSION COULD SINK WARD & CO.

ANALYSIS: UNSUSTAINABLE GROWTH PLANS LEAVE LEGACY COMPANY EXPOSED.

EXCLUSIVE: LETTER OF INTENT WITH ORION CAPITAL INCLUDES UNDISCLOSED CLAWBACKS.

Graphs borrowed from the deck James had sent to the board were annotated with footnotes that didn’t exist in his version. Anonymous sources “close to the board” parsed his growth plan with the kind of expertise that takes more than a weekend with a consultant. One pull quote, memorably cruel because it was true: “You can staple wings to a toaster, but you shouldn’t call it a plane.”

“Who leaked this?” James asked, eyes flicking from headline to headline as if by speed he could make them change.

“We need to see this,” Anna said again, because that’s what a crisis is: not what you want to see, but what you must.

He looked up. The directors’ faces were stone. The kind of stone that remembers water passing over it for a century and is patient with erosion.

One by one they closed their folders; one by one they rose. No chair scraped loudly. No voice raised. They left him with his slides and the bouquet on the table and the ghost of a woman who had smiled rather than begged.

By noon, counsel had been contacted. By three, the independent directors had called for a vote. By evening, James’s ID card returned a small red light when he tried the glass doors. Security didn’t drag him. He walked out under his own power—but power has a sharp sense of humor about who it belongs to.

He found me anyway. Of course he did.

He appeared in the doorway to my office—the one that used to be mine, now another woman’s who would ask me months later how I took my coffee—and closed the door. He didn’t knock. Men like James believe in the dramatic.

“You,” he said. His voice cracked. The arrogance had fallen off him like paint in weather. Underneath: a boy who never learned how to lose. “It was you.”

I leaned back in my chair. The bouquet lay wilted between us, drooping heads like gossip. “You fired me, James,” I said. “You ended my time here.”

His jaw tightened. He waited for me to take the credit he needed to blame me with. I didn’t give it to him. I let the silence do its work. If there is a sound to certainty drowning, I learned that day what it is.

He left without slamming the door. He is not, no matter what his résumé implies, stupid.

That night, at home, I stood with my hands on a kitchen counter dented by a pan I’d dropped on a Sunday when a phone call interrupted me and decided I wasn’t going back to any room that treated my presence like luck. I had been offered a board seat at a smaller firm three months prior and postponed the decision. I called them. “I’m in,” I said. The woman on the other end let out the kind of breath people take when they have been waiting on a delivery truck all day and it finally turns the corner.

The next morning, the calls began.

“Selene, I’m with StratCap—”

“Selene, we don’t like surprises, but we like lies less—”

“Selene, would you be willing to consult—”

A miniature storm. I didn’t need a title. The people who make decisions know the difference between a signature and a name. The bouquet dried in a vase over the weekend, and when I brushed my hand against a petal, it broke like burnt paper. I didn’t feel grief. I felt the click of a trap I’d spent a year setting, closing where it should.

On Monday, a courier delivered an envelope in the old-fashioned way: hand, seal, weight. Inside: a letter from the chair of the board. We would like to explore a formal advisory arrangement regarding succession planning, capital allocation, and governance. The word governance made me smile in a way growth never had. We set a date.

What James did not understand, and maybe never will, is that power is not an office. It is a map of conversations, and I already knew the routes by heart.

Part 2

The glass tower that used to hold my office throws a shadow across a block at noon. I walk under it sometimes the way people revisit old schools—out of habit, not hunger. My name isn’t on the door anymore. Good. Names on doors are photographs of sunsets: pretty, inaccurate, yesterday. The women at reception don’t look up when I pass because I do not go inside. One of them is new. One of them is Anna, and she winks when no one is watching.

It is a mistake to think a story ends because the villain exits. Villains are rarely villains to themselves. They are choices in suits. They are people who look at climbing equipment and decide the ropes are optional. James’s rope snapped. It made a sound. We went on.

The advisory agreement came with conditions I wrote in a coffee shop because why not: quarterly sessions with the board, monthly breakfasts with the CFO and COO, a clause that obligates the company to staff compliance with adults, a line that forbids any “major strategic shift” without an explicit vote recorded in minutes. The lawyer on the other end said, “This is unusually… blunt.” I said, “I don’t have time for whispered implieds.” He laughed. He signed. People are living tired of euphemism.

We established a practice I called The Friday Page. One page, no adjectives, numbers for adults, charts only if they say more than a sentence can. It was an old journalism trick I’d stolen years ago. The CFO loved it because you can hear lies in adjectives and not in charts. William loved it because men who like to make decisions quickly love anything that makes decisions quick. The board loved it because they got to feel like they were in the know without reading five hundred pages designed to ensure that they never would be.

I built a small firm because women who get divorced from titles do not go back to maiden names; we write new ones. I named it Harbor Thirty because I like the way that sounds in a mouth. The work was simple because simple is heavier than clever: teach boards how to read, teach executives how to listen, teach founders how to woo capital without marrying their cap table. I kept it small on purpose. Five people. Two analysts who understood the difference between a variance and a story about a variance. One partner from an old rival who called me and said, “I owe you an apology; it’s the only currency we don’t inflate.” One assistant who kept my calendar like a saint presides over a relic. One me.

It would be sexy to pretend I became a vigilante for women in rooms they expect coffee from. I did not. I became an expert who got paid. I took calls, and I calculated fees based on the difficulty of convincing people they are not their own best plan. Sometimes I failed. I learned to leave.

James trod water for three months at a “stealth” consultancy and surfaced with a startup in a field that would have embarrassed a high school boy in 1998. He tried to raise a small round and found out that footing matters more when you stand in front of a cliff. The articles had made his name spell danger; the Google results turned investors’ index fingers to the back button. He wrote a Medium post that never used my name and used the word learned nine times. I didn’t read it. Sandra texted me lines. I didn’t understand the importance of institutional knowledge. I over-indexed on vision. She added a popcorn emoji, and I asked about her son. Small talk is freedom.

Two days before Ward & Co.’s annual meeting, the building’s newest secretary—fresh cheeks, sharp bun—burst into the boardroom breathless. It has become a ritual, almost theatrical: breathless entry, news that must be seen. We laughed, because sometimes you must let your body know that it is not about to die.

“Apologies,” she said, cheeks pink. “You need to see this.” She had a tablet. She placed it on the table. Fewer headlines this time, more citations. A macroeconomic note that said something smart about interest rates; an industry piece that said something truer about labor; a small photograph of a factory floor showing six men and three women wearing the same shirts in different sizes.

“It’s us,” Dana said quietly.

No one argued. We have never been the kind of company that confuses a lens with a mirror. William, older now in the way men get handsome when they stop thinking it matters, looked at me.

“We need to do the thing,” he said.

“What thing?” a director asked, new to our short-hand.

“Tell the truth,” I said. “And fix what the truth made obvious.”

We told the truth: cost of capital up, cost of selling down, cost of pretending equal to zero because we stopped. We fixed what we could: a painful decision to shutter a line that had sentimental value and unkind margins; a less painful decision to double the size of support because when you answer the phone, revenue’s second cousin shows up with a casserole; a decision, simple and late, to let customer success schedule the launch calendar and not marketing. We wrote it on one page. No adjectives. The stock dipped for a quarter. Then it didn’t. The director who had asked “what thing” bought me coffee and said, “I thought truth-telling was for personal lives.” I said, “It is. That’s why it works.”

The bouquet has a habit in this story: it realigns itself with endings and beginnings. On a Tuesday, a man in his twenties brought me peonies in a brown paper sleeve after a talk I gave at a university about power and the silence it likes to be confused with. He said, “My mother watched the live stream of that board meeting where you didn’t say his name. She said she replayed it. She said you taught her something about—” He stopped. He held the peonies out like paper boats. “Thank you,” he finished. I put them in a jar next to my sink and thought about all the women who will never be in rooms like the one I was in and still deserve that kind of end.

When James called me—once, late, from a number that made itself look like a telemarketer—I let it go to voicemail because I do not need to know what my past wants from me. I listened later in the way you listen to recordings of your own voice and learn to forgive. “Selene,” he said. “I—” Silence. He hung up. The message lasted three seconds. It will be on his phone bill as a proof of something he thinks he attempted. It will not be on mine.

The old meeting room has a new table. It is longer, inexplicably. The chairs got reupholstered. The plaque in the hall with the list of CEOs has four names now. William’s twice. James’s for six months, then a hyphen, then the ambiguous interim. Names on plaques are little mausoleums. Sometimes they are museums to patience.

I’m not interested in hauntings. I’m in the business of air.

The morning after we closed the Harbor Thirty fund—a small pool of money that lets us put skin where our advice is—I walked to the Meridian Hotel and sat in the same chair where I had asked seven people if they trusted James with their money. The room smelled like bacon and linen again. The manager recognized me and pretended not to. Discretion is a religion there.

A young woman at the next table scrolled on her phone with the fury of someone who wants to be asleep instead. She had notes open in a document labeled Board Prep. She had typed and deleted the sentence We need to be honest three times. I turned away; I am not anyone’s story. She coughed, a small sound. I looked back. She looked at me and then past me, as if I were a poster of someone she’d once admired and was now embarrassed to be caught looking at.

“Say it like this,” I said without planning to. I pushed my coffee toward her, wrote on a napkin. “This is the number we told ourselves. This is the number the world told us. This is the number we can live with. Then stop talking.”

She read it. She nodded. She took the napkin. “Thank you,” she said. “Are you—”

“No,” I said, smiling. She laughed. We practice anonymity in doses.

At home, on my desk, I keep the wilted bouquet pressed in a book. The petals have become tissue thin and still hold a hint of scent when you press your nose against the paper. I do this sometimes when I need to remember how it felt to be told my time was over by a man who didn’t understand what time is.

Time is a map, not a clock. It winds. It loops. It leads you into rooms where you thought you would beg and teaches you to smile instead.

The secretary still bursts into rooms, sometimes—breathless, bright—with news that must be seen. Only now she does it because she knows that truth delays are more expensive than truths told on time. In one meeting she arrived red-cheeked with a one-page note: a supplier in trouble, a strike looming, a shipment stalled at a port where someone else’s politics played king. We adjusted. We survived. We bought the supplier a seat at our table and did not tell anyone we had saved ourselves by refusing to make them a villain.

I don’t keep bouquets in boardrooms anymore. I keep water. I keep pens that work. I keep the habit of asking one question that flips rooms over:

“Do you trust this with your money?” (When I say this, I mean him, her, me, us, the policy, the market, the story we prefer.)

My name is not on the door. It is on a calendar. It is in a phone. It is in scripts whispered in bathrooms before meetings where people need to say brave sentences to men who think they are weather.

The day we closed a sale we had chased for nine months without lying once, I bought myself a bouquet on the way home from work. Peonies, freesia, eucalyptus. I carried them up the stairs like a promise I had already kept. At the top of the landing, I paused and looked out toward the glass towers that shine at dusk like a city apologizing for the day. I thought of the sentence that had begun this version of my life.

“Selene Ward, your time is over.”

I smiled again.

Because it wasn’t.

It had begun.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

It’s 7 AM and You’re Still Sleeping Get Up and Make Me Breakfast— My Mother-in-Law Screamed at Me… CH2

It’s 7 AM and You’re Still Sleeping? Get Up and Make Me Breakfast— My Mother-in-Law Screamed at Me… Part…

My Husband’s Family Called Me “Useless” — But My Dad’s Response Left Them Speechless. CH2

My Husband’s Family Called Me “Useless” — But My Dad’s Response Left Them Speechless Part 1 No one ever…

My Aunt Claimed I Owed Her $30K for “Raising Me” – The Judge’s Response Left Her Speechless…. CH2

My Aunt Claimed I Owed Her $30K for “Raising Me” — The Judge’s Response Left Her Speechless… Part 1…

My Husband Was Celebrating with His Mistress… So I Arrived with Her Fiancé. CH2

My Husband Was Celebrating with His Mistress… So I Arrived with Her Fiancé Part 1 What would you do…

Abandoned and erased by family, I returned after 9 years. Mom snapped: ‘Why is this failure here?’ CH2

Abandoned and Erased by Family, I Returned After 9 Years. Mom Snapped: “Why Is This Failure Here?” Sister Smirked: “You…

My brother’s fiancee slapped me in front of 150 people at their wedding. CH2

My brother’s fiancée slapped me in front of 150 people at their wedding because I didn’t give them my house….

End of content

No more pages to load