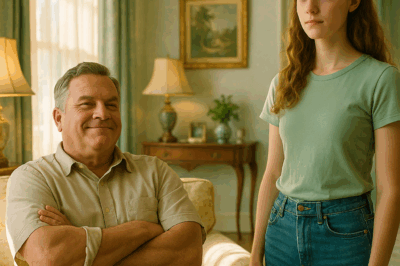

I was about to knock on my parents’ door when I heard them tell my brother, “Don’t stress about the debt. Your sister will cover it.” She never says no to family.

Part One

The hallway carpet muffled everything—my footsteps, my breathing, the bloodthrob pounding at my temples. I had the check in my hand, crisp and unbelievable even after an entire 12-hour shift of glancing at my badge photo and asking, Is this really my life? Is this really my bonus? Fifteen thousand dollars. For a nurse, that feels like sunlight breaking through clouds.

I never got to knock.

“Don’t stress about the debt,” my father said on the other side of the door in his accountant voice, the one he used when he wanted other people to feel calm about bad numbers. “We’ll make your sister pay. She’ll never say no to family.”

On instinct, my hand froze in the air. The weight behind the door—their voices, the cheap bravado—held me there.

“Dad,” my brother Alexander drawled, lazy and oily like always. “You’re a lifesaver.”

“Your sister’s a lifesaver,” my mom corrected, tone light. “She does love to be needed.”

They laughed.

I didn’t open the door. I didn’t say, Surprise, I have good news, too. I didn’t walk in and accept their careful choreography where I am always—always—the responsible one with deep pockets and a deeper well of guilt.

I turned around and walked back down the stairs I’d climbed a thousand times as a kid and across the front lawn and into the cool of my car. The check sat on the passenger seat like a stranger.

The drive home evaporated. Muscle memory got me there: right on Maple, left on Lincoln, over the little rise that makes the skyline look like it’s about to leap into your lap. I parked, and for the first time since nursing school, I cried so hard I had to put my forehead on the steering wheel and ride it out like a storm. I cried for twelve-year-old Vanessa who spent her allowance on class snacks because Mom had forgotten it was her turn. I cried for nineteen-year-old Vanessa studying pharmacology at three in the morning and catching the 5 a.m. bus because there wasn’t money for a car—for her, there was never money for her. And then I stopped crying, wiped my face, and felt something unfamiliar and clean slide into place: resolve.

I moved every dollar out of my account the next morning.

The credit union doors had barely unlocked. I sat with a banker named Stephanie who looked like the kind of woman who keeps receipts for receipts. We opened new savings and checking with security features that made my mother’s “emergency” calls useless. We updated beneficiaries. We removed my mother as an authorized user on my card—a “temporary thing” she’d asked for seven years ago and never relinquished. I set up alerts to ping me if any attempt at access failed. I left feeling like someone had handed me a set of keys that actually belonged to me.

Then I went to the person who understands charts and leverage like a second language.

Joseph’s office looks like a Scandinavian “before and after” reveal, all light wood and good chairs. He’s been my adviser for three years, ever since my first solid stretch as a day trader made me realize money can be a tool or a trap depending on whether you acknowledge gravity. I slid the check into his hand and then slid the other thing across the table: a spreadsheet titled Family Contributions.

“Jesus, Vanessa.” He said it softly. “I knew you were generous. I didn’t know you were a line item.”

Roof: twelve grand. Bear Lake taxes: forty-three thousand, five hundred. Mom’s knee rehab: eight thousand, two hundred. Alexander’s car and “emergency” cash and little things that aren’t little: everything added up in relentless black type. Opportunity cost—what those dollars would have done if they’d stayed invested—wrote a quieter, meaner story in the margin.

“You want to sue?” he asked after he’d counted twice, which he always does.

“No,” I said, surprising both of us. “I want documentation. I want to know exactly what I gave the last five years. I want to be done.”

He referred me to Victor, a forensic accountant with patient hands and a teacher’s smile. Victor turned my meticulous notes into something a court would respect if it needed to: notarized summaries, bank statements tabbed with sticky flags, a line graph that looked like a heartbeat. Between the three of them—Family, Portfolio, Opportunity—my history lay on the table like a body I could finally see from above.

That night I called Jessica, my best friend, who has the rare gift of telling you the truth kindly. “They’ve been grooming you for this since you were ten,” she said when I finished. “The responsible one. The rescuer. They built a button, and they’ve been pressing it ever since.”

“I heard them laughing,” I said, and it sounded small and enormous at the same time. “Not even trying to pretend.”

Jess didn’t say I told you so even though she has, for years, in careful ways. She said, “Move your money, document everything, and do not give them another cent. I’ll drive you to the bank. I’ll sit in the lobby while you do it. Then we write you some scripts.”

She meant therapy scripts, which turned out to be the best armor I’ve ever owned.

Dr. Carter is the kind of therapist who looks like she could braid your hair while dismantling a bomb. She listened to my story and nodded like she’d heard sixty versions of it this summer alone. “You were assigned the role of caretaker,” she said. “Your brother was assigned the role of the one who gets cared for. Your parents reinforced it every time you complied. When you change, they will escalate. Expect guilt, rage, triangulation. Expect them to tell other people you’re unstable. Expect them to say ‘family’ as if it were a debit card.”

“What do I say back?” I asked.

“You don’t explain,” she said. “You don’t defend. You don’t persuade. You say: I’m not available for that. I’m making decisions that align with my goals. I love you, and this is my boundary. Then you hang up and call me if you shake.”

Sunday dinner came like always. Roast chicken. Perfect table. The blue house that has always been the set for a sitcom I didn’t choose to star in.

I brought a mid-range Pinot instead of the $80 bottle Dad prefers when he wants to perform appreciation. Mom hugged too long and said, “We missed you on Tuesday. Emergencies, right, sweetheart?” with a tone that tried to recloak the betrayal in domestic banality. Alexander arrived late in a blazer that cost more than my monthly grocery bill, with the confidence of a man who has never read a bill.

“Big news,” he said as he sat. “An investment opportunity. Family only.”

I chewed. I swallowed. I said, “Tell me.”

He launched into Futurecoin Technologies, all untraceable founders and guaranteed returns, and I felt my training kick in the way it does when a code is called at 3 a.m.—heart rate up, brain cool.

“And the seventy-five thousand?” I asked when he finally paused.

The entire table went jambled: forks clinked, eyes flashed. Mom recovered first with the bright sturdiness of someone who has decorated a story for decades. “Vanessa, you misunderstood. We were simply talking about how we could all come together as a family.”

“I don’t misunderstand numbers,” I said.

Dad went for authority. “Eavesdropping is juvenile.”

“I was about to knock,” I said. “Then I heard my parents and my brother discuss how to lie to me to extract seventy-five thousand dollars. You suggested ‘medical bills,’ Mom. Alexander suggested an ‘investment opportunity.’ You said guilt always works.”

Alexander’s charm cracked down to the ugly thing it covers. “You love to feel superior, don’t you? Nurse Manager Vanessa. Maybe spread a little of that wealth around.”

There it was. The marrow. Not gratitude. Not partnership. Entitlement.

“I’m not funding your life anymore,” I said. “I moved my money. I’ve documented everything. I want a relationship with you that isn’t based on what I’m paying for. If that’s not possible for you, I will be okay.”

Dad’s ears went red the way they do when the Bulls lose. “After all we’ve done for you.”

“Name three things,” I said quietly. “Name one thing you did for me that you didn’t do twice over for Alexander.”

Silence can be as honest as numbers.

“I love you,” I said, and meant it in the way you love people who gave you a name and a home and a template for what not to tolerate. “I’m going home. Don’t call me about money again.”

They did, of course. Immediately. And then Aunt Maria called. And Cousin Danielle. And Grandmom. The chorus sang: family family family. Dr. Carter’s scripts held. “I’m not available for that.” “I hear that you’re disappointed.” “This is my boundary.”

On Wednesday, my supervisor called me into her office with that look managers have when they’ve been put in the position to deliver a personal message. “Your father reached out,” she said, eyebrows compromising. “He’s concerned about your ‘mental health’ because you’re making…different choices.”

“I’m in therapy,” I said plainly. “I’m setting financial boundaries with my family.”

She sat back like a prayer had been answered. “Good,” she said. “Tell me if you need time off. And for what it’s worth, we’ve seen this before.”

On Friday, my cousin Diana, who works at the bank no one in my family thinks she can see through them at, called on her lunch break. “I probably shouldn’t say this,” she whispered, and then said the most honest thing I’d heard all week. “They took out a second mortgage three months ago. Seventy-five thousand. I think it’s gone.”

Of course. The plan had never been get Vanessa to pay; it had been get Vanessa to refill the bucket after they’d tipped it into Alexander’s hole.

On Saturday, Dad convened a family meeting to paint me as a traitor. He did not expect Uncle Pete to say, “If she’s paid the lake taxes for five years, she owns a stake.” He did not expect Aunt Catherine to shove my packet at his chest and say, “You always said you were fair.” He did not expect Alexander to glower and glower until the glower looked like fear.

And he certainly didn’t expect Megan, two weeks later, to text, I used my trust to pay the Bear Lake taxes and the deed amendment. You own 25%. I told Dad to split the trust. He’s seeing Joseph Monday.

I stared at the screen until the numbers blurred. Not because I needed the property or the money. Because some Schrodinger part of me had never opened the box to see if my sister might choose me over the script.

Then I went to the lake and painted the guest room a ridiculous, perfect color and slept with the windows open while the water made a sound that felt like permission.

Part Two

Six months later, the leaves turned the city into a confetti machine. I became Director of Nursing for our critical care division—a title that means fewer codes and more budgets, more mentoring, more ability to fix systems that burned us down during the worst years of our lives. I hung a print in my office that says Boundaries are love in action and watched nurses cry in front of it because someone had put truth on paper.

My condo is mine in a way it never was before. I painted the living room terracotta with a roller and a playlist that made my cat, Luna, tilt her head like she was trying to understand me. I found a community at the climbing gym of all places, because learning to fall and trust the rope is weirdly good practice for learning you can’t catch everyone and shouldn’t try.

The calls tapered off. The guilt storms passed. The group texts turned into weather reports (“first snow!”) and neutral holidays (“pie recipe?”). I didn’t go to Thanksgiving. I hosted a Friendsgiving and cried over green beans because someone else sharpened my knives without asking. Two days later, Aunt Catherine sent me a photo of Dad and Mom at a table with fewer chairs and a caption that said, Next year: new traditions.

In October, my father had a heart attack. It wasn’t catastrophic—one stent, two days in the hospital—but mortality has a way of scraping varnish off people. I learned about it from Diana, not from him. I stood in his room doorway the way I had stood in so many doorways as a nurse, and for the first time in my life, my father’s face lit up simply because I was there.

“Vanessa,” he said, voice rough. “You came?”

“Of course,” I said, because I am who I am, even when I’ve learned not to set myself on fire to keep other people warm.

We were quiet. After a while he said, “The cardiologist says stress contributes.” He stared at the ceiling. “Financial stress.”

He told me about the second mortgage I already knew about. He told me about the retirement withdrawals. He told me about how he had spent two months trying to engineer a way to ask me for thirty thousand dollars without making it look like an ask. He told me, quietly and like it hurt, that Alexander had left for California with a suitcase and a promise and an address that turned out to be a P.O. box.

“Your mother thinks he’ll come back,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s good.”

He looked at me then with eyes that looked older than his. “I was wrong,” he said. Not we were wrong. I. “I taught you that love is an invoice. I taught your brother that love is an unlimited line of credit. I am sorry.”

It wasn’t everything. It didn’t confess the laughter in the hallway that will always live in a small bruise in my chest. It didn’t pay me back for five years of roof and taxes and tears. But it was the first true thing he had offered me that wasn’t language to get to an ask.

“I can’t fix your finances,” I said. “I can’t fix Alexander. I can’t be the lever you pull when something breaks.”

He nodded like he had practiced the gesture and meant it this time. “I didn’t ask you to come for anything,” he said. “I just—I wanted you to know I know.”

Mom arrived twenty minutes later wearing grief like a perfume she wasn’t sure fit. She kissed me with a kind of ferocity that felt like apology and then asked, gently and unsurprisingly, if I still knew the name of the physical therapist who had been kind to her knee. She slipped once, “We’re a little tight right now,” and I said, “I’m not available for that conversation,” and she nodded and asked what Luna eats now that she’s grown.

You don’t undo thirty years of pattern in one heart attack. But you can write over it in careful handwriting until the old script is hard to see.

We sold the Bear Lake house in January. It turned out to be a kindness disguised as a loss. We sat at the closing table with a lawyer who clicked through numbers like deals were just math and not ghosts. Dad slid the proceeds into an account that a fee-only adviser supervised. He texted me screenshots that looked like Bible verses to him: contributions, budget, no cash advances. He told me the new counselor said making lists helps. “I love lists,” I wrote. “You should have had me teach you earlier.” He wrote back a heart he probably had to ask Megan how to find.

Megan called from a coworking space with a plant wall and wrote I got into the accelerator and I have a mentor who is not a man who calls his mother for rent. She split the trust like she said she would; Dad whined, Mom cried; she stood anyway. She paid back the last two property taxes voluntarily even though it wasn’t required, and then she said, No more—pay your own mortgages. She stopped being beautiful scenery in other people’s stories. She got an EIN instead of a new watch. We argue about fonts now. It’s heaven.

On a rainy Tuesday in March, I met Dad for coffee. He wore a jacket that fit a man who had let go of a lake house and an illusion. He stood up when I arrived, a small ceremony I noticed and put in my pocket.

“How’s work?” he asked, because it’s the only clean entry point we’ve ever had.

“Good,” I said. “We got three out of five nurses through a leadership program last quarter. They’re starting to ask for what they need. We built a preceptor structure that doesn’t burn people out. It feels like…a system that works for humans.”

He nodded like I was teaching him a thing and not reporting. “Your mother’s making marinara like it’s a religion,” he said. “She started a book club. They read the book this time.”

We grinned at each other like strangers who might become friends.

“Do you ever think about coming back to Sunday dinner?” he asked cautiously. “No pressure. The lasagna is better.”

“I might,” I said. “On the condition that no one mentions money and no one asks what I drive. On the condition that when Alexander calls from California, you send him to a program instead of a bank.”

“That last one is hard,” he said.

“That last one is love,” I said.

He looked down at his hands. “I’m learning,” he said.

I took a sip of coffee and decided to make a vow that belonged only to me. I will not be the person I was in the hallway outside your door. I will not stand with a gift in my hand and let your laughter teach me how small you think I am. I will bring dessert when I want to. I will leave when I need to. I will love you with a locked wallet and an open hand.

Spring came early. The city shrugged off the last snow like a dog out of a lake. Luna chased a sunbeam across the floor and lost. I put on my running shoes and a playlist that makes me forget I am a person other people have opinions about and go along the trail that smells like thawed earth and possibility.

My phone buzzed. A text from Mom with a photo of a cake that looked like it had survived a battle and a caption that said, I tried a new recipe; I think I overbeat the eggs; I miss you. I wrote back, I miss you too and You don’t have to use six eggs; three will do.

She wrote, come Sunday? and then, after a minute, no pressure.

I stared at the screen and felt the old fear like a shadow, and then I felt the new thing which is like a door in my chest: openable, closable, with a handle only I can reach.

Yes, I wrote. I’ll bring salad. I’ll leave by eight. I’m not available for financial discussions. A heartbeat later: we’re not available for those either with a smiling face that looked like she’d learned how to emoji from Megan.

Sunday, I stood on their porch again. Same blue house. Same geraniums. New person in the body suit of an eldest daughter.

I was about to knock when I heard my father’s voice, thinner than the last time I’d heard him through a door. “Let’s make sure to send Megan the handyman number,” he said. “She shouldn’t be up on a ladder alone.”

“Vanessa will boss us all around about safety,” Mom said, the smile in her words so warm it fogged the glass.

“She gets to,” Dad said. “She knows things.”

The doorbell camera blinked. I knocked. Mom opened the door with tears in her eyes and a dish towel over her shoulder and didn’t step aside until she’d squeezed my hand and said, “I’m glad you’re here.”

I set the salad on the counter and took a deep breath and felt the boundaries settle around me like a well-tailored suit. The lasagna was good, but the best part was when Dad got up to do the dishes without Mom prompting, and when the conversation skated close to remember when, I said, I’d like to talk about now, and they said, okay.

After dinner, I put my coat on and kissed my mom’s forehead and told Dad to text me his cardiologist’s name so I could look up his outcomes like a daughter who is also a nurse and a guardian of her own peace. He nodded. “I told him you’d check his stats,” he said. “He said to tell you he’s in the top decile, whatever that means.”

“It means I won’t lecture you tonight about what you eat,” I said. “But I will always lecture you about who you let use you.”

He smiled, like somebody who had finally learned why being the responsible one isn’t a curse—it’s a superpower when you aim it at the right target.

On my drive home, the city looked like a place worth fighting for. I parked, went upstairs, and logged into my brokerage account. My Future climbed in steady, beautiful green. I smiled at the graph like it was a friend. I closed the laptop and stood at the window and thought about the person who had walked away in a hallway rather than knock, and the person who had knocked tonight because she’d decided the terms.

Some debts you don’t pay in dollars. You pay them by refusing to believe you owe them.

And some families you don’t lose—you redefine them until they fit.

The next morning, I put a sticky note on my mirror. Boundaries are love in action. Under it, I wrote, including self-love. Then I picked up my bag and went to a job that makes me proud and a life that finally feels like it belongs to me.

END!

News

My father told me I wasn’t his biological daughter just so he could exclude me from my grandmother’s inheritance. “Only blood relatives deserve the family fortune,” he said proudly. I looked him in the eye and asked, “Are you sure you want to stick to that?” He nodded without hesitation. ch2

My father told me I wasn’t his biological daughter just so he could exclude me from my grandmother’s inheritance. “Only…

My dad handed my inheritance to his new stepson. He told me, “He deserves it more than you.” I gave a quiet smile and walked off. But at the lawyer’s office, everything changed. ch2

My dad handed my inheritance to his new stepson. He told me, “He deserves it more than you.” I gave…

Nobody from my family came to my graduation, not even my husband or kids. They all went to my brother’s barbecue instead. ch2

Nobody from my family came to my graduation, not even my husband or kids. They all went to my brother’s…

My mom texted me, “We changed all the locks. You don’t live here anymore.” ch2

My mom texted me, “We changed all the locks. You don’t live here anymore.” Part One The text arrived…

At my sister’s wedding reception, the screen flashed: Infertile, divorced loser, high school dropout. ch2

At my sister’s wedding reception, the screen flashed: Infertile, divorced loser, high school dropout Part One The first laugh…

My spiteful sister-in-law suddenly played nice and invited my son to an adventure park with her daughter for a cousin’s day out. I agreed, but 2 hours later, my niece called me in tears, saying, “Mom said it was just a prank, but he’s not waking up.” ch2

My spiteful sister-in-law suddenly played nice and invited my son to an adventure park with her daughter for a cousin’s…

End of content

No more pages to load