I Warned the HOA for Months About a Landslide — They Ignored Me and Nearly Lost Their Lives

Part 1

The hill moved first.

Not a little shiver in the dirt. The slope behind the clubhouse actually breathed, bulged outward, groaned, and then let go in one grinding roar.

Mud, rock, landscaping timbers, and several thousand dollars’ worth of custom HOA shrubbery tore loose like a brown tsunami and surged toward the clubhouse windows.

Inside, the monthly HOA meeting froze. The projector went black. Someone screamed. Someone else yelled, “My Lexus!” At the podium, HOA president Cheryl Havversham stood with her mouth open, clutching a stack of violation notices as if sheer disapproval might be enough to stop gravity.

On the other side of the glass, a thick wall of mud slammed into the back of the clubhouse, shattered the patio doors, and poured inside like chocolate concrete.

In the second row, I didn’t scream. I just muttered, far too quietly for anyone to hear over the chaos, “I sent six emails about this.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

My name is Daniel Ruiz. I’m thirty-nine, a structural engineer for a small geotechnical firm that most people only think about when something cracks, leaks, or falls over. My idea of a good Friday night is double-checking load calculations and making sure buildings do not slide downhill. My wife calls it “professional paranoia.” She’s not wrong.

Six months before the clubhouse turned into a mud aquarium, all I wanted was a quiet place to drink coffee and watch the sunrise without the earth attempting to assassinate the neighborhood.

Mara and I had just bought a place in Hillside Terrace, a shiny new subdivision carved into the side of a big clay hill just outside town. Every house had “views.” The brochure was full of phrases like Live Above It All, Elevated Living, and Panoramic Slope Estates.

The engineer part of my brain translated all that as: We took a chainsaw to a hill and are now hoping the dirt behaves out of politeness.

Still, the price was good. The commute was short. The schools were decent. The house had big windows that made Mara sigh in that way that says, Please stop overthinking and let me have this. So I did what any responsible professional would do.

I moved in and immediately started worrying about drainage.

Enter: Cheryl Havversham. HOA president. Retired interior stylist. Full-time menace in capri pants.

Cheryl treated Hillside Terrace like she was the elected governor of gravity. She had opinions about everyone’s mulch color, the exact millisecond trash cans should be at the curb, and how many minutes a garage door could be open before it became a “security eyesore.” She also had zero understanding of civil engineering, geology, or water management.

Unfortunately, she had 100 percent control of the “beautification” budget.

At my first HOA meeting, I noticed the giant site map hanging on the clubhouse wall. A massive steep slope behind the community pool was labeled STABILIZED CUT – DRAINAGE EASEMENT.

Except when I walked outside later, the real hill didn’t match the map. The drainage swale along the top—where stormwater was supposed to be safely collected and diverted—was full of decorative river rock, ceramic planters, and artfully placed boulders.

I stared at it with my eyebrows slowly climbing. That was the beginning of the nightmare.

The first red flag came with the rain.

A late-spring thunderstorm rolled in, the kind that empties an entire lake onto your ZIP code in an hour. I watched through our back windows as sheets of water hammered the slope behind the clubhouse.

Where there should have been a clear, engineered channel at the crest of the hill, there was water trying to find a path around Cheryl’s “cohesive aesthetic enhancements.” It flowed around ceramic pots, over boulders, and straight into the soil.

Within an hour, the hill started developing long vertical cracks, the kind we call tension cracks—nature’s version of “brace yourself.”

I grabbed an umbrella and walked up the top path. The soil oozed under my shoes. The drains at the ends of the swale were partially blocked by decorative bark and those river rocks Cheryl had bragged about in the neighborhood newsletter. Down below, the retaining wall at the base of the hill had a slight, but unmistakable bulge.

My professional brain started screaming.

The next morning, I did what engineers do when they’re worried: I wrote an email.

Hi Cheryl,

I’m a structural engineer, and I have serious concerns about the slope and drainage behind the clubhouse. The recent landscaping changes are obstructing the drainage swale. After last night’s storm I observed cracking and movement in the soil, and bulging in the retaining wall. This presents a potential landslide risk.

I strongly recommend a geotechnical inspection and immediate remediation. Happy to provide a report or meet on site.

Best,

Daniel Ruiz, P.E.

I attached photos. I highlighted the cracks. I circled the blocked drains. I even attached the relevant sheet from the original grading plan I’d pulled from the city website, the one that said in all caps: DO NOT OBSTRUCT DRAINAGE CHANNEL.

Two days later, I got her reply.

Hi Daniel,

Thanks so much for your input! We actually had the landscaping professionally designed for aesthetic cohesion. We’re not looking to make any changes at this time, but we appreciate your enthusiasm for the community.

Best,

Cheryl Havversham

President, Hillside Terrace HOA

Enthusiasm. That word did things to my blood pressure.

Two weeks later, another storm rolled through. More rain, more cracking, a little more bulge in the wall. I took more photos. This time, my email included phrases like “imminent slope failure” and “life-safety issue.”

Her response:

Daniel,

We have reviewed your concerns with the Board. The original plans were approved by the developer and the city. There is no issue. Please refrain from spreading alarm.

Best,

Cheryl

“Spreading alarm.”

So I did the only thing someone with anxiety and a conscience can do: I documented absolutely everything.

I took daily photos of the hill. I logged rainfall totals. I printed out the grading plans and highlighted the “do not obstruct” language until the paper looked like it had jaundice. I mapped the cracks on graph paper like it was my personal science project.

That was when the first threat showed up—and it wasn’t from the hill.

One afternoon there was a bright orange notice taped to my front door.

UNAPPROVED EROSION CONTROL MEASURES. REMOVE WITHIN 7 DAYS OR BE FINED.

The offending “measure”? A small line of sandbags I’d placed along my backyard fence, just in case the slope above decided to liquefy while we slept.

The violation photos attached to the notice were almost artful. My sandbags, zoomed in, circled in red.

I wrote back:

These are temporary safety measures due to the unstable slope condition I’ve documented repeatedly. Removing them increases risk to my property and family.

Daniel

Her answer came within hours, faster than she’d ever replied about a genuine hazard.

If you do not remove them, you will be fined $50 per day. Hillside Terrace is not a construction site.

Cheryl

I removed the sandbags because the last thing I needed was a lien on my house. But I didn’t stop.

I started copying the entire HOA board on my emails. I printed my latest set of photos and slid them under the clubhouse office door. At one meeting, I even brought a flashlight, walked everyone out back, and shined the beam along the jagged fractures in the retaining wall.

“Look at the bowing,” I said. “This wall is moving. This isn’t optional maintenance. You need a professional inspection.”

Cheryl pulled her lips into what she probably thought was a cool, authoritative smile.

“Daniel, with respect,” she said, “this sounds like a hypothetical problem. We can’t just spend association funds every time someone gets nervous about a crack in the ground.”

“You don’t have a crack,” I replied. “You have an impending landslide.”

“What we do have,” she said, tapping her printed agenda, “is an issue with people parking slightly crooked in their driveways. Let’s stay focused.”

The other board members—two guys whose only real concern was keeping the pool open on time and a woman who thought “geotech” was a smartwatch brand—nodded along.

The hill kept moving.

The turning point started with an email and ended with a government seal.

After my fourth ignored warning and one more “please stop scaring people” reply, I went around the HOA. I filed a formal complaint with the city building department. I attached everything—photos, drawings, emails, rainfall logs. I used phrases that make municipal engineers sit up.

Public safety hazard. Documented movement. Non-compliance with approved grading plans.

I expected a bureaucratic shrug in six to eight weeks.

Instead, I got a knock on my door five days later.

The man on my porch wore a city badge, steel-toed boots, and the expression of someone whose coffee had just been interrupted by the phrase “potential landslide.”

“I’m Ben Carter,” he said, shaking my hand. “City engineer. You’re the guy sending the apocalyptic hill emails?”

“That’s me,” I said. “I brought props.”

We spent an hour walking the slope. I pointed out the tension cracks, the bulging wall, the clogged drains, the decorative boulders sitting exactly where water wanted to go. He took photos, measurements, and notes, his frown getting deeper with each step.

“How long has it been like this?” he asked.

“Months,” I said. “The HOA president thinks I’m ruining ‘the vibe.’”

Ben snorted. “Here’s what’s about to ruin the vibe.”

Three days later, the city sent a formal Notice of Hazardous Condition to Hillside Terrace HOA. They ordered a geotechnical evaluation of the slope and warned that failure to act could result in fines and closure of community facilities.

Cheryl’s reaction was immediate and unhinged.

She called an emergency HOA meeting at the clubhouse. The subject line of the email blast: URGENT: One resident is threatening our community amenities.

“This,” she announced, waving the city letter like a parking ticket she intended to litigate personally, “is what happens when one person decides to sabotage our community.”

Everyone turned to look at me.

I sat in the back row holding a folder full of soil reports and printouts.

“We are being unfairly targeted because someone doesn’t like the landscaping,” Cheryl continued. “The city is overreacting. Our developer signed off. The county signed off. This is politically motivated.”

I raised my hand. “This isn’t political,” I said. “It’s geology.”

“We are not going to be bullied into spending tens of thousands of dollars just because you like to play scientist,” she snapped.

“I am a scientist,” I said.

“We’re tabling this,” Cheryl declared. “The board will respond to the city and explain that there is no actual risk.”

She did more than respond.

She emailed the city claiming I had a personal grudge, that I had altered the drainage myself, and that I was “mentally unstable and causing panic in the neighborhood.”

Unfortunately for her, lying to city officials about a documented safety hazard is not only stupid. It’s permanent. It goes in the file.

Ben’s reply was polite but firm: Her opinions did not override observable physical conditions, and failure to comply would lead to enforcement action.

Cheryl forwarded that to the board with one line:

We do not negotiate with bureaucrats.

Two weeks later, the city issued another order. If a licensed geotechnical consultant wasn’t hired within ten days, they’d close the pool and clubhouse until the slope was evaluated.

Cheryl doubled down again. She wrote an all-caps post in the neighborhood Facebook group about how “our amenities are under attack due to one resident’s false reports,” and begged everyone to attend the next meeting to “stand up for our community and stop unnecessary spending.”

It worked. It was the most attended HOA meeting in Hillside Terrace history.

Unfortunately, it was also the night the hill decided it was done playing nice.

Part 2

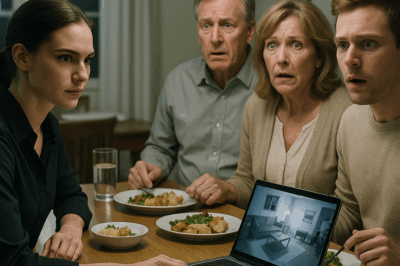

The night of the landslide started the way every HOA meeting does: with passive aggression, stale cookies, and too many people pretending to care deeply about mailbox paint.

Outside, the sky was a swirling mess of dark clouds. A slow, steady rain had been falling all day. The clay hill behind the clubhouse had soaked it up like a sponge.

By seven that evening, the ground was saturated.

I sat near the back, watching the projector flick through the agenda. Cheryl stood at the front, hair sprayed into hurricane-proof immobility, voice dripping patience and contempt in equal measure.

“The city engineer is being dramatic,” she said as a few raindrops ticked against the windows. “They love to overstep. The slope has been there for years. It’s fine.”

She cleared her throat.

“Now, about Daniel’s unauthorized sandbags—”

A thunderclap rattled the glass. The rain intensified, drumming on the roof, sluicing down the slope behind us.

I glanced at the back wall. My temples started that specific ache I get when someone ignores load limits.

Cheryl clicked to the next slide: a pie chart titled AMENITY ENHANCEMENT PRIORITIES. A big green slice was labeled “Pool Furniture Upgrade.” A tiny sliver said “Unnecessary Geotechnical Study.”

“As you can see,” she said, “the board recommends diverting funds from this so-called study to—”

The lights flickered.

Someone near the back turned to look out the windows. “Uh,” they said slowly, “is the hill supposed to look like that?”

I stood.

The hill had developed a long, unbroken crack near the top, running like a scar across the slope. Water poured into it in a steady line, vanishing beneath the surface. Halfway down, a bulge swelled outward—bigger than it had been that morning.

I walked quickly to the back doors. The retaining wall down at the toe of the slope bowed more visibly now, like a tired back.

Every training course I’d ever taken started screaming in my head.

I turned back to the room. “Everyone,” I said loudly, “we need to clear the clubhouse. Now.”

Cheryl laughed, high and tight. “Daniel, stop trying to dramatize this. We are having a meeting.”

“Look out the window,” I said.

People did. A murmur rippled through the crowed. Parents shifted, pulling kids closer.

The hill moved.

Not much. Just enough that the shrubs tilted and one of Cheryl’s precious landscaping timbers popped out like a tooth from a jaw.

The engineer in me knew what that meant. The human in me stopped waiting for permission.

I walked straight to the fire alarm pull by the door and yanked it.

The siren erupted. Red strobes flashed. Everyone flinched.

Cheryl shrieked. “You can’t do that! That is a violation of—”

“The hill is failing!” I shouted over the alarm. “Grab your kids and get out. Away from the back wall. Move!”

Something in my voice cut through the chaos. Maybe it was the certainty. Maybe it was the fact that the floor itself had started to vibrate, ever so slightly.

People began to move—some grumbling, some scared. Chairs scraped. Kids cried. The alarm wailed.

In the middle of it, Cheryl marched toward me like a furious goose.

“I’m calling the police,” she yelled. “You have no authority—”

Behind her, through the glass, the hill let go.

It was like watching slow motion and fast forward at the same time. The entire midsection of the slope separated from the rest with a deep, tearing sound, a slab of soaked earth and rock sliding down as a single massive piece.

It accelerated, picking up debris—timbers, shrubs, chunks of clay. Water frothed around it. The whole thing became a moving wall.

“Move!” I roared.

I grabbed Cheryl by the arm—harder than politeness allowed—and yanked her sideways just as the landslide hit the clubhouse.

The glass doors exploded inward with a sound like a cannon. A brown wall of sludge and shattered landscaping punched into the back of the room where the last two rows of chairs had been thirty seconds earlier. Tables flipped. The projector crashed to the floor. A couch floated briefly before being pinned against the far wall by the slurry.

People screamed for real now. Not HOA-meeting outrage—primitive, gut-deep terror.

“Front exit!” I shouted. “Stay away from the windows. Take the side path, not the lower slope.”

Mara had been at home with our son, thank God. I didn’t have to find them; I just had to get everyone else out.

I shoved Cheryl toward the front doors. She stumbled, splattered with mud and rain, still clutching her stack of violation forms like a life raft.

We spilled outside into cold, pounding rain.

Behind us, the hill kept slumping. Smaller slides broke off and chased the main flow like aftershocks, burying half the patio and a good chunk of the pool fence. A couple of cars parked in the “perfectly safe overflow parking” behind the clubhouse disappeared up to their windows in mud.

Within minutes, sirens filled the night. Fire trucks. Police cruisers. An ambulance. Somewhere in the tangle of lights, I saw Ben’s city truck pull up, his jaw clenched so tight I could see it from across the lot.

Firefighters swept us into rough lines, counting heads, checking for injuries. Miraculously, we’d gotten everyone out of the back of the room. There were scrapes, bruises, one broken wrist from someone tripping over a chair, and a mild concussion. It could have been a disaster scene. Instead, it was a near miss.

“If we’d stayed another minute,” one firefighter muttered to me as he sloshed through the mud-filled clubhouse, “we’d be zipping up bags.”

“You said you warned them,” he added, almost as an afterthought.

“For four months,” I said, watching Cheryl sit on a folding chair under a tarp, her hair plastered to her head, shock turning her face gray. “They gave me a violation for sandbags.”

The next few days were a blur of neon vests, caution tape, and news vans.

The city slapped big yellow UNSAFE – DO NOT ENTER placards on the ruined clubhouse. The pool area, half-buried in clay, looked like a drained aquarium someone had dumped a construction site into.

The local paper ran a front page story:

ENGINEER WARNED HOA ABOUT LANDSLIDE RISK FOR MONTHS. THEY IGNORED HIM.

The article quoted excerpts from my emails, Cheryl’s dismissive replies, the city’s unanswered orders. It printed before-and-after photos of the hill and a close-up shot of the blocked drainage swale, still artfully decorated with ceramic pots, now half-buried in mud.

The online comments were vicious. People used phrases like criminal negligence and power-tripping HOA tyrant. Strangers from other neighborhoods chimed in with their own Cheryl stories. The power had shifted completely out of her manicured hands.

But mud is temporary. The real punishment, I knew, would come from paper.

I didn’t have to wait long.

Part 3

In the weeks after the slide, Hillside Terrace went from “up-and-coming luxury community” to “cautionary tale.”

The city formally condemned the clubhouse and pool until costly repairs and full slope stabilization could be completed. Orange fences went up. Kids pressed their faces to them like it was a zoo exhibit. Parents pulled them back, whispering about lawsuits.

The HOA’s insurance company sent their own engineers. They climbed over the debris, took measurements, and combed through documents with the grim efficiency of people who spend their lives trying to decide whether they have to cut a check.

The answer, at least in full, was no.

Apparently, intentionally ignoring written safety warnings from both a licensed engineer and the city, then lying about it in writing, has consequences even insurance companies won’t swallow.

I got the first call from a lawyer two weeks after the slide.

“Mr. Ruiz?” she said. “My name is Rachel Kim. I represent several homeowners in Hillside Terrace. We’re considering a class action against the HOA for negligence. Would you be willing to share your documentation?”

I looked at the color-coded binder on my kitchen table, tabs sprouting from it like a strange paper flower. “I have… some,” I said.

Her laugh was dry. “The city’s report is brutal. They concluded the original design had adequate drainage and stabilization. HOA landscaping changes obstructed that drainage and increased saturation. Warnings were ignored. The landslide was ‘foreseeable and preventable.’”

Foreseeable and preventable. Lawyer catnip.

The HOA held its first post-disaster meeting in the parking lot, because the clubhouse now sported a large crack where the back wall used to be.

They rented a pop-up tent. Cheryl stood under it like a dethroned queen, makeup reapplied, hair restored to its usual shellacked helmet. She looked smaller, though. Like someone had let the air out.

“We have been unfairly targeted,” she began, raising her voice over the murmur of gathered neighbors and the hum of a nearby news van. “The landslide was an act of God.”

“God didn’t move those drains,” someone shouted.

“God didn’t email the city saying Daniel was crazy,” another added.

That one stung her. You could see it.

Greg, a usually quiet neighbor who lived two houses down from me, held up his phone. “We read the emails, Cheryl,” he said. “The city FOIA’d everything. You told them Daniel was mentally unstable and that he altered the drainage. You lied.”

A rumble of agreement moved through the crowd.

Cheryl’s smile wobbled. “We were trying to avoid unnecessary panic,” she said. “This lawsuit talk—this isn’t helpful. We should be united. Our community is hurting.”

A woman near the front—Maria, mother of three, frequent receiver of “Your kids left chalk on the sidewalk” notices—cleared her throat.

“I’d like to make a motion to remove the entire board,” she said. “Effective immediately. For cause.”

For a moment, the only sound was the wind smacking the tent flaps.

Then hands shot up.

The board’s attorney, a man whose suit looked like it resented being rained on, stepped forward. “Let’s slow down,” he said. “The bylaws have a specific process for—”

“They also have a specific process for addressing life-safety issues,” Maria snapped. “Which this board ignored.”

The attorney hesitated. The optics were bad, and he knew it.

“Fine,” he said. “We’ll record a vote.”

They tried to do it with paper ballots. That lasted thirty seconds. People started calling out their votes.

“For removal,” Maria said.

“For removal,” Greg echoed.

“For removal,” another neighbor chimed in, voice shaking with anger. “My car is still half-buried behind the clubhouse because you said it was ‘perfectly safe.’”

The chorus continued. A few timid “against” votes surfaced—friends of Cheryl, or people who were just allergic to conflict—but they were drowned under the tidal wave of “for.”

The motion passed. Officially. Loudly.

Cheryl looked around as if she’d come to a party and found someone else’s name on the cake.

“You can’t just— I have dedicated years to—”

“You nearly got us killed,” someone shouted from the back. “Because you thought decorative rocks were more important than listening to an engineer.”

Her face went pale, then flushed a mottled red, then pale again.

The HOA’s attorney cleared his throat. “Ms. Havversham,” he said carefully, “you should also be aware that given the findings in the city report, and the correspondence on record, there is a possibility you could be held personally liable in the negligence suit.”

“Personally?” she whispered. “But… the board…”

“The board is being named as an entity,” he said. “You, as president, are being named individually.”

He might as well have dropped a second landslide on her.

The special assessment letters landed in mailboxes a week later.

Every homeowner would have to pay $42,000—each—for slope stabilization, clubhouse reconstruction, additional insurance, and legal fees.

The reaction ranged from stunned to furious.

“Forty-two grand?” Maria said, waving the letter on my porch. “We don’t have that. My husband’s a teacher. We’re barely paying the mortgage as is.”

“You can arrange a payment plan,” the letter said. “Or apply for a hardship deferment.”

“Or we can sue,” Greg muttered.

They did.

Rachel’s class action suit moved faster than anyone expected. The PR around the landslide had embarrassed the city council; they wanted it resolved. The developer, dragged back into the drama, produced their original plans and inspection sign-offs with the eagerness of someone shoving exculpatory evidence across a table.

In deposition, I sat under fluorescent lights and answered the same questions half a dozen different ways.

“When did you first observe cracking on the slope?”

“When did you first communicate concerns to the HOA?”

“How many times?”

“What response did you receive?”

“Did anyone from the HOA ever consult you in your professional capacity?”

“No,” I said again and again. “They did not.”

Cheryl’s deposition transcripts leaked, of course. In them, she insisted she had “relied on the original approvals” and that “one resident” had “a history of oppositional behavior.”

Rachel slid the transcript across the table to me one afternoon. “She says you have ‘anger issues,’” she said. “Anything you want to tell me?”

“I got angry when my neighbors nearly died in a preventable landslide,” I said. “Does that count?”

She smiled faintly. “The judge will probably agree with you.”

When the settlement finally landed, it was messy. Insurance paid for some of the stabilization. The developer chipped in a small portion to avoid public trial. The HOA, as an entity, was responsible for the rest.

Cheryl’s personal liability had been negotiated down, but not away. She exhausted her savings and refinanced her house to cover her share. A lien went on her property.

She put it on the market three months later. The listing photos were carefully cropped to avoid showing the still-scarred hill.

Mara watched me reading the real estate ad at the kitchen table.

“Do you feel bad?” she asked.

“About what?” I said. “Physics?”

“About her losing the house,” she said gently.

I stared at the photo of Cheryl’s staged living room, all gray and white and aggressively neutral.

“I feel bad that it took a slide for anyone to listen,” I said. “I don’t feel bad that ignoring reality has consequences.”

Mara rested a hand on my shoulder. “You did everything you could,” she said. “More than most would.”

I knew that, logically. Emotionally, it sat in my chest like a rock.

One afternoon, months after the dust and mud had finally settled, I saw Cheryl at the grocery store.

She was in the produce section, staring at a pyramid of avocados as if they’d personally inconvenienced her. The sharpness had gone out of her posture. Her immaculate capris had been replaced by plain jeans. No clipboard. No stack of violation notices. Just a woman picking through bruised fruit.

She saw me. For a second, something like the old fire sparked in her eyes. Then it fizzled.

“I suppose you’re happy,” she said finally. “You got what you wanted.”

“What I wanted,” I said, keeping my voice level, “was for the hill not to come down on us.”

She flinched.

“I never meant for anyone to get hurt,” she said. “I was just trying to keep the neighborhood… nice.”

Keeping the neighborhood “nice” had turned out to be the ugliest thing she’d ever done.

“I know you didn’t mean it,” I said. “But meaning and impact are different. You ignored warnings. That has consequences.”

She looked away first.

“I heard you’re on the new board,” she said, bitterness creeping back in. “How’s that working out for you? Enjoying the power?”

“Mostly I enjoy the committee name,” I said. “Slope Safety and Infrastructure. We’re very glamorous.”

She snorted despite herself.

To my surprise, what I felt looking at her wasn’t triumph. It was a strange mix of anger, pity, and relief. The fight was over. The hill had spoken. Gravity had finally voted.

Now we just had to figure out how to live on it.

Part 4

Being right doesn’t automatically make you popular.

When the dust settled and the lawsuits stopped being daily entertainment, Hillside Terrace still had to fix a literal hole in the ground and a metaphorical one in everyone’s trust.

The interim board—made up of volunteers from the “concerned residents committee”—asked me to serve as vice president, specifically in charge of “engineering and safety.”

“You realize that’s not a ceremonial title, right?” I said at the first meeting.

“None of them are,” Maria replied. She’d been elected president, mostly because she’d had the courage to say aloud what everyone else was thinking: that Cheryl had to go. “We’re rebuilding from scratch.”

The first order of business was hiring a real geotechnical consultant. The second was listening to them.

The firm we brought in wasn’t mine—conflict of interest—but I knew the senior engineer, a guy named Sam Walker. We’d gone to the same conferences. I trusted him.

He walked the hill with a squad of technicians, took core samples, and ran slope stability models that made my head ache sympathetically. His report was blunt.

“The original cut is steep, but not inherently unstable if properly drained,” he told the board in a meeting that actually started on time. “The problem was all the junk in the swale. Remove the obstructions, install a proper subdrain system, regrade the mid-slope, build a real retaining structure at the toe, and you’ll be okay.”

“How much?” someone asked.

He named a number that made everyone wince but not faint.

“Cheaper than another landslide,” I said.

“Cheaper than another lawsuit,” added Maria.

The work took months. Excavators chewed away at the damaged slope. Dump trucks hauled out load after load of saturated clay. A soldier pile wall went in at the base—massive steel beams drilled deep, with concrete lagging between them. French drains were installed at multiple levels, wrapped in filter fabric, connected to real, actual outlets.

The decorative river rock and ceramic pots never came back.

I spent most evenings out there, standing at the perimeter fence, arms crossed, watching.

“You know you’re not on the clock,” Sam said one day, coming up beside me.

“Old habits,” I said. “I sleep better when I know where the water’s going.”

He nodded. “You did good, you know,” he said. “Most people look at cracks, shrug, and call them ‘texture.’ You pushed.”

“I had a personal stake,” I said. “My house. My kid.”

“That helps,” he said. “Still doesn’t make it easy.”

When the wall was finished and the drains connected, the city inspected, signed off, and quietly removed the UNSAFE placards from the clubhouse shell.

Rebuilding the structure itself took another year. The insurance only covered barebones; the community had to choose between “luxury upgrades” and “not draining our savings again.”

We chose cheap, durable, and boring. Waterproof flooring. Simple furniture. No indoor water features, no matter how much someone on the new social committee pined for a giant fish tank.

At the grand reopening, we held the first official “New HOA” meeting.

The agenda was short.

First: an update on the stabilization project.

I stood at the front, a little uncomfortable, and clicked through slides showing the new wall, the drains, the slope profile.

“We’ve designed for a hundred-year storm,” I said. “Rainfall like the night of the slide won’t saturate the soil the same way. The factor of safety is significantly higher now.”

Ben, sitting in the second row, gave a small approving nod.

“Second,” Maria said, taking the podium, “we have some proposed bylaw changes.”

We’d spent months drafting them. They were simple.

Any modification to common-area drainage or grading would require sign-off from a licensed engineer and the city. Any safety concerns raised in writing had to be documented, investigated, and responded to in writing. No more verbal handwaves.

And: no board president could serve more than two consecutive terms.

“I make a motion to adopt the changes,” Greg said.

“Second,” someone else chimed in.

The motion passed unanimously.

Afterward, people milled around the rebuilt clubhouse, sipping coffee from the new, less breakable mugs, looking out at the slope that had nearly killed them and now sat, armored and drained, like a tamed animal. Still wild, but watched.

Mara slipped an arm through mine. “You look tired,” she said.

“Engineers don’t get tired,” I said. “We just… lose efficiency.”

She smacked my arm lightly. “You worried less this last storm,” she said. “You slept.”

“I did,” I admitted.

“Progress,” she said.

That night, as we walked home under a sky finally clear of storm clouds, my son—seven now, all knees and questions—pointed up at the hill.

“Is it still mad at us?” he asked.

“The hill?” I said. “Hills don’t get mad. They just do what physics tells them.”

“Are we still dumb, then?” he countered.

“Some of us were,” I said. “We’re trying to be less dumb.”

He considered that. “Okay,” he said. “Can I roll down it now?”

“No,” Mara and I said in unison.

Two years later, I found myself in a very different room, talking about the same hill.

The state legislature had convened a hearing on hillside development and HOA oversight. Somebody in a blazer had decided our little slide was a good case study.

I sat at a long table with a microphone and a nameplate: DANIEL RUIZ, P.E., HILLSIDE TERRACE RESIDENT.

Across from me, a row of lawmakers shuffled papers.

“Mr. Ruiz,” one of them said, “in your professional opinion, what was the primary failure in your community’s situation?”

“Hubris,” I said before I could stop myself.

A few people chuckled. I let the silence stretch a bit.

“Technically,” I said, “there were three failures. Poor education—people in charge didn’t understand the infrastructure they were responsible for. Poor process—no requirement for expert review of changes. And culture—a board that punished people for raising concerns rather than thanking them.”

“Do you believe stronger state regulations could help?” another asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But regulations are only as good as the people enforcing them. HOAs need to treat safety like they treat paint swatches—with obsessive attention.”

That line made the local news.

After the hearing, in the hallway outside, a man in his fifties approached me.

“I’m president of an HOA up in Crestview,” he said. “We’ve got a slope behind our pool, too. After seeing what happened to you, our board wanted to add some boulders ‘for ambience.’ I showed them the article about your landslide. The rocks stayed in the catalog.”

I shook his hand. “Good,” I said. “Tell them you’ve already paid for the entertainment.”

Back in Hillside Terrace, life settled into something that almost resembled normal.

Kids splashed in the reopened pool. The clubhouse hosted birthday parties, book clubs, and one extremely earnest karaoke night. The slope sat quietly behind it all, drained and reinforced, a constant background reminder that the earth doesn’t care about property values.

We installed a small plaque on the back patio, near the new doors.

IN RECOGNITION OF THE RESIDENTS WHO EVACUATED THIS BUILDING ON THE NIGHT OF THE 20–– LANDSLIDE, AND OF THE ENGINEERS, FIREFIGHTERS, AND NEIGHBORS WHO PREVENTED A TRAGEDY.

LET THIS HILL REMIND US TO RESPECT GRAVITY, LISTEN TO WARNINGS, AND PUT SAFETY BEFORE AESTHETICS.

My name wasn’t on it. I preferred it that way.

Part 5

Years passed.

The hill stayed put.

Trees planted along the slope’s benches grew, their roots threading through the stabilized soil. The soldier pile wall darkened with weather. Moss crept into the grooves. If you didn’t know the story, it looked like it had always been there.

Most new residents didn’t know the story.

They saw a well-built wall, a nicely graded hill, a somewhat plain clubhouse, and a president named Maria who smiled a lot but went very still when anyone suggested “fun little changes” to the drainage.

Sometimes, at new-neighbor barbecues, the question would come up.

“So what’s with the plaque?” a new arrival would ask, flipping burgers. “Something happen here?”

One of us old-timers would tell the story, condensing panic and mud and litigation into a digestible anecdote.

“Landslide,” we’d say. “Ignored warnings. We got lucky. We fixed it.”

Their eyes would go wide. They’d nod. Life would go on.

My son grew up. My marriage weathered the strain of lawsuits and late nights and eventually settled into a new shape—one that included more walks, fewer arguments about email tone, and a mutual understanding that my professional paranoia had its uses.

One autumn evening, almost a decade after the slide, I sat on the rebuilt clubhouse patio with Ben and Sam, three engineers with gray sneaking into our hair, watching a storm roll in over the hills.

“This one’s going to dump,” Sam said, looking at the radar on his phone.

“Good test,” Ben added.

We sat in silence as the rain started, gentle at first, then heavier. Water ran into the swale, disappeared into the drains, reappeared obediently at the outfalls farther down, just as designed.

The hill stayed quiet.

Ben leaned back in his chair. “You ever think about moving?” he asked.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Then I look at that wall and think, at least here I know exactly what’s under my feet.”

Sam laughed. “That’s the most engineer thing I’ve ever heard.”

Across the patio, Maria was setting up for a community meeting—this time about a modest playground upgrade. The agenda taped to the door included a line that made me smile: “5. Review of drainage implications.”

As the meeting started, I slipped out. I’d promised Mara I’d be home in time to help with dinner. On my way to the parking lot, I nearly collided with a teenager barreling around the corner, earbuds in.

“Whoa,” I said, grabbing his shoulder before he could wipe out on the wet concrete. “Slow down.”

“Sorry,” he said, tugging a bud out of his ear. “Grandma wants me to put the chairs out.”

“Which grandma?” I asked, recognizing his face but not placing it.

“Cheryl,” he said.

The name stopped me.

“You’re… her grandson?”

“Yeah,” he said warily. “You know her?”

“We used to work together,” I said carefully. “On the HOA.”

He squinted at me. “You’re the landslide guy.”

“I guess I am,” I said. “How’s she doing?”

He shrugged. “Okay, I think. She moved into the condos down on Maple after she sold the house. She does, like, pottery now. Makes weird bowls. Keeps telling me not to ignore deadlines.” He rolled his eyes. “She mentioned you once. Said she should’ve listened. Then said not to tell you she said that.”

A laugh snuck out of me. “Your secret’s safe,” I said.

He darted off toward the storage closet, leaving me standing in the rain with the strange, unexpected warmth of that admission.

On the drive home, I thought about Cheryl. About the woman who once threatened to fine me for sandbags, standing in a community center somewhere, teaching people how to center clay instead of control a neighborhood.

People change. Hills shift. Walls hold.

At home, Mara had the radio on and a pot of something that smelled like home bubbling on the stove.

“How was the meeting?” she asked.

“Short,” I said, hanging up my jacket. “Boring. Perfect.”

She smiled. “Any landslides?”

“Not tonight,” I said. “Not here.”

After dinner, as I washed dishes and listened to my son—now in college, home for the weekend—complain about group projects, my phone buzzed.

It was an email from a stranger. Subject line: HOA + Slope Question.

I hesitated, then opened it.

Hi Mr. Ruiz,

I got your contact from a friend of a friend who works at the city. I’m on the board of an HOA in another town. We’re thinking of “enhancing” the hillside behind our community center with some landscaping, and I remembered reading about what happened in your neighborhood years ago.

Would you be willing to look at our plans and tell us if we’re doing anything stupid?

Thanks,

Olivia

I stared at the screen. Mara dried her hands and looked over my shoulder.

“You going to answer?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said slowly. “Yeah, I am.”

I typed:

Hi Olivia,

Short answer: yes, I’m happy to take a look. Long answer: I’ll tell you what our former HOA president told me wasn’t important, and what nearly cost people their lives.

Start with the drainage.

Best,

Daniel

I hit send.

Outside, the rain drummed steadily on the roof. Water ran down gutters into downspouts, out onto the street, into storm drains, and eventually, somewhere far away, into a river that didn’t care about cul-de-sacs or clubhouses or the human tendency to assume the ground will always stay still.

I cared.

Enough to send emails. Enough to pull alarms. Enough to stand on cold patios and argue about walls.

That’s the thing about warnings. They’re only annoying until the moment they’re not. After that, they become the difference between a headline and a story you tell on a quiet night, years later, to remind yourself that once, when the hill started to move, you did, too.

And this time, at least, we moved just in time.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Family Ignored My Graduation — Then My $5 Million Penthouse Made Them Pay Attention…

My family skipped my graduation, but the moment my $5M penthouse made real-estate headlines, everything changed. A single text from…

I Caught My Parents On Security Camera Planning To Give My Brother My Apartment – So I Set A Trap & Exposed Everything At Dinner…

I Caught My Parents On Security Camera Planning To Give My Brother My Apartment – So I Set A Trap…

My husband yelled “How dare you say no to my mother, you stupid!” At the family party, he even sma…

My husband yelled, “How dare you say no to my mother, you stupid!” At the family party, he even smashed…

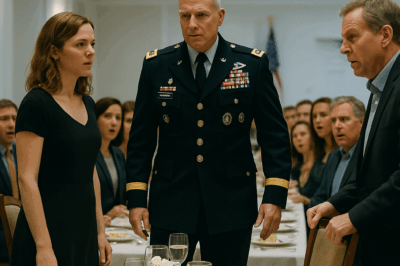

“Someone Like You Doesn’t Deserve to Sit Here.” My Dad Pulled the Chair Away.Then a General Stood up

“Someone Like You Doesn’t Deserve to Sit Here.” My Dad Pulled the Chair Away. Then a General Stood Up …

My CIA Husband Called Out of Nowhere — “Take Our Son and Leave. Now!”

My CIA Husband Called Out of Nowhere — “Take Our Son and Leave. Now!” Part 1 The sound of…

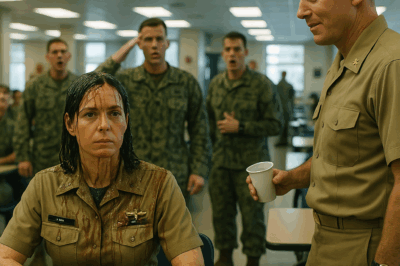

Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral

Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral Part 1 By…

End of content

No more pages to load