I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me…

Part One

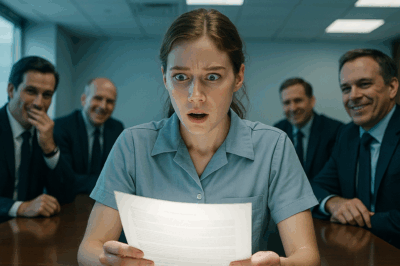

I had already read the letter ten times, maybe more. My eyes kept scanning the same shaky lines, as if by rereading them enough, the words might rearrange into sanity:

Rachel, I’m sorry. I can’t do this anymore. I’ve fallen in love with someone else. We’re leaving today for another city. Please tell the kids I love them. —Eric

Just his name at the end. No confrontation, no courage—only a coward’s signature under a demolition order. For a long time I sat staring at the grain of our kitchen table while the walls quietly moved inward, as if the house itself were embarrassed to be seen with me.

“Mom, are we having dinner tonight?”

Noah—fourteen, solemn, protective already—stood in the doorway, backpack on one shoulder. My reflex was to hide the note. He was too quick. He read it once and set it down, folding it with a care that broke me more than tears would have.

“I kind of figured,” he said in that gravel-new voice boys get when the world starts handing them man-sized moments. “Have you tried calling him?”

I had, and I had called his office, too, only to learn he’d resigned with the same casual cruelty that emptied drawers and vanished photographs. He’d planned his escape like a business trip—resignation, new itinerary, detour around the lives he’d built. We held the conversation grown-ups have when the people supposed to be grown-ups refuse to. Noah kept his hands flat on the table and his voice calm. We said words like mortgage and school and what next while Rosie hummed to herself in the living room and Eli blew pencil eraser dust off his math homework to make his own weather.

In the weeks that followed, I sold jewelry for grocery cash and gave away winter boots I had saved for a never-taken trip. I listed the flat-screen and watched a college kid carry it away like a prize. I put my resume in a file that looked like a biography of someone I no longer was. Fear—sharp, metallic—sat where appetite used to live.

Then a voice I didn’t know called and said, “Is this Rachel Whitaker? You registered at the employment center as a former nurse?”

“Yes,” I said, and made my voice choose trust.

“I’m Claire Henley,” she said. “We’re seeking a live-in caregiver for a private client. It’s not hospital work, but your background is ideal. And if you have children, the property can accommodate them.”

For a beat I couldn’t answer. I stood in my kitchen with a pawn ticket in my pocket and a calendar that looked like a cliff and said, “Yes. I’m available.”

In Reinbeck the next morning, glass and steel rose like new money learning how to be old. Claire met me in a corner office that smelled faintly of lavender and stubbornness. Her suit was immaculate; her eyes were kind in a way people forget to be when their suits are immaculate.

“Your credentials are solid,” she said. “You’ve been out of the field for a few years, but you have critical-care experience. The man you’d be caring for is Mr. Franklin Montgomery, retired investor. He’s paralyzed from the waist down with cardiac and pulmonary complications. Mentally, he’s as sharp as he is impossible. He’s burned through caregivers like fire through newspaper. We’re looking for somebody who won’t take it personally.”

“What counts as personally?” I asked.

“Anything he says after breakfast,” she said, and didn’t smile. Then she turned the tablet, and the number beside weekly salary removed the air from the room.

The gate to the Montgomery estate made a noise like wealth learning to whisper. The guest house they gave us looked like a storybook pushed through a reality show—brick and ivy, four bedrooms, a sunny kitchen where hope could sit at the table and not feel out of place. Noah and Eli raced upstairs arguing about which window framed the trees better. Rosie pressed her face to the glass and breathed a fog-heart on it and wrote HOME? with one finger. I wiped the condensation line away and nodded.

“Mr. Montgomery will see you now,” Lucas Bennett, the estate manager, said with the practiced gentleness of a man who spends his days preventing fires you can’t see.

The widower sat in a motorized chair with a wool blanket over his knees and a scowl that had probably outlived his first fortune. His hair was as white as the linen on the table behind him; his eyes were as sharp as an accountant’s pencil.

“So,” he said, not looking up from his tablet, “you’re the latest.”

“I can shave you now if you’d like,” I said, because fear makes me either silent or reckless and I was tired of being silent. “You’re starting to look more homeless than millionaire.”

He looked up. A flash of something like amusement crossed his face. “At least you’ve got guts,” he said. “We’ll see how long they last.”

They lasted through personal remarks that forgot where decency lives. Through mornings where coffee was not strong enough and patience was a muscle I had to ice afterward. Through a midnight emergency when his chest seized and the room tilted and all the cruelty he had spent on me took one look at the oxygen mask in my hand and went quiet. My body remembered procedures my file said were outdated; my hands moved in a choreography their owner could still perform after three years out of a hospital. The color crawled back into his face. He opened one eye and croaked, “Took you long enough.”

“No coffee,” I said. “Just competence.”

Days found their shape. I learned how to measure pain by the way his jaw clenched and when to argue with him and when to let him pretend he had won. The children learned how to make friends with a kitchen they could help in and paths that led to curiosity instead of dead ends. Lucas learned to time errands so I forgot why I loved being alone.

One Saturday he drove me into town to a place with high windows and yeast in the air and a dish he promised would rearrange my heart back into my body. We talked like people who have been waiting for someone to ask them a question they actually want to answer. By the time the last slice of khachapuri was gone, I had said the words He left us in a room that did not turn away. Lucas didn’t interrupt, didn’t fix, didn’t offer solutions wrapped as compliments. He said, “We all get broken a little. The trick is not letting the broken part name you.”

The next week I met Eric in a restaurant with clean napkins and a view he would have chosen when he meant to make me feel small. He was ten minutes late and tan in the way a man gets when he has been outside in a happiness he isn’t entitled to. “Rach,” he said. “We could try again.”

He reached across the table. I pulled my hand back and said the words I had planned in the bathroom mirror with my mouth shaking, “We are here to finalize the divorce.”

He spoke the way hard men speak when the soft gets pulled out of their mouths, mean because they are afraid of being not-mean. “You think some charity job makes you too good for me?” he spat. “You couldn’t even keep me—how are you going to keep a family?”

A chair scraped behind me. Lucas’s shadow fell across the table. “I suggest,” he said in that indoor voice men who could be dangerous practice for when they don’t want to be, “you lower your voice.”

The next voice made me blink. “Or don’t.” Mr. Montgomery stood in the doorway on his cane as if gravity had been waiting for him. “If you make a spectacle, I’ll have brandy with my dessert.”

Eric puffed himself up because some men do that when threatened. Then Lucas reminded him gravity is a real thing. The punch was clean; the silence after it was not. Mr. Montgomery clapped once—actual applause. “Marvelous,” he announced. “Utterly restorative. Shall we order pie?”

On the ride home, my humiliation did not outweigh the relief of being defended in public by men whose admiration didn’t require me to be smaller. I expected consequences. Instead I got tea in a study where once I had only gotten insult. Mr. Montgomery stared at the window until his reflection answered and said, “I have been married four times. I have money and no heirs. I am not easy to love.”

“Most people aren’t,” I said, and watched the sentence land somewhere inside him he hadn’t allowed visitors.

By late summer the children had names for every bird in the orchard. The hallways, once anxious, learned to echo laughter without sounding surprised by it. Rosie performed recitals for the wooden banister; it approved every piece. Eli left his sketchbook on a table where Mr. Montgomery could see it and later found a set of charcoal pencils he hadn’t asked for. Noah helped Lucas fix a gate simply because the gate had sighed when he walked past it.

The day Mr. Montgomery thanked me for saving his life, he said it like a complaint: “You’re underpaid.” I told him I wasn’t.

He adjusted the blanket over his legs and asked, “What does being safe feel like?”

“Like exhale,” I said, and meant it.

Part Two

Autumn introduced itself with honesty—cool edges, yellow edges, mornings that require commitment. By then the estate had become a map my feet could walk in the dark. It had also become a stage where old ghosts came to remind the living who had scripted the first act.

Eric called first, because men like him cannot abide not having the last line. He tried soft, then legal, then a low roar about custody and Child Protective Services and that house isn’t safe.

“It’s safer than you,” I said when he paused to breathe. “And there’s a recording of you in a restaurant being the man you are. File if you like. I’ll bring pie.”

His next move was the one I hadn’t prepared for because I didn’t believe he would risk the children’s shame to soothe his own. He arrived at our approach road with a woman holding her phone like a weapon and a man whose outfit told me he had learned what ethics were and chosen a different hobby. He intended humiliation. He got a gate and a voice over an intercom that said, “This is private property, sir. Step away.”

He made noise that would have worked eleven months ago. Lucas walked down the drive like gravity and daylight had joined forces. Two local officers who owed Helen the cook a favor because she’d fed them through a snowstorm that time parked behind him. Mr. Montgomery sat in his motorized chair under the portico like a king who had come out to watch his jesters and had not been impressed.

“You don’t have the right,” Eric shouted, voice cracking. “They’re my kids. She is a—” He searched for a word that would make me disappear. Braver men had tried. He settled for nothing dressed as liar.

Mr. Montgomery’s voice carried easily. “Unlike you, son, I’ve learned to read,” he said with the lazy contempt of a man who has seen ninety years and doesn’t have time to pretend anymore. “There’s a divorce decree. There’s a police report. There’s a restraining order in a file if you insist on making our afternoon entertaining. Go home.”

Eric tried a swing at dignity and missed. The woman beside him—who had been filming expecting fireworks to sell to the internet—captured instead the look on Eric’s face when he realized nobody here was going to play his game. The police escorted him to his car; Lucas escorted his dignity to the curb. The gate closed with a rustle. Birds shook leaves back into place.

That night Mr. Montgomery called me to the study. He tapped the seat across from him. “I don’t like being embarrassed,” he said. “But I liked that one.”

“I don’t want this to be a war,” I said because I meant it.

“Then win fast,” he said, as if strategy could be harvested from courage. He passed me a card. “Call this lawyer in the morning. She’s the kind that makes men nervous because she remembers everything.”

It took eight weeks of hearings and more paper than trees should suffer. It took me learning how to keep my jaw parallel to the floor while Eric’s lawyer described me with adjectives that didn’t apply. It took me presenting a neat stack of affidavits and videos and printouts and the sentence the judge liked best: “No, Your Honor, he hasn’t asked to see his children since August.” We left with sole custody and a piece of paper that made Mr. Montgomery’s portico an absolute boundary instead of a suggestion.

In the midst of all that, his health tilted.

It wasn’t dramatic. No sirens. Just a weariness you could not shake off and a cough that took too much of him with it. He stopped insulting breakfast toast. He started asking for stories instead—about Noah’s algebra joke, about the drawing Eli made of the orchard in winter, about how Rosie had learned to braid her hair like a crown.

The morning the doctor lowered her voice and used the word comfort, I sat on the drive and let the sun burn the chilled fear out of my hands. He had asked once what being safe felt like. It turned out it felt like sitting with a man you had learned to respect while the calendar reduced itself to second chances and you did not look away.

He asked to be moved to the garden. We complied like a battalion. The pergola threw shadows like cathedral lace. Helen smuggled forbidden honey into his tea. Lucas stood in the doorway because some men understand guarding a threshold is a holy occupation.

“Tell me something true,” Mr. Montgomery said on the last afternoon when the light was the color of promises kept.

“You were wrong about me,” I said, smiling so he would forgive me. “I never stop for coffee when you’re dying.”

He coughed what might have been a laugh. “You’re underpaid,” he said, because it was his line and we both knew it. Then, after a while: “There’s a letter in my desk. For you. Don’t read it until—” He didn’t finish the sentence because he didn’t need to. He closed his eyes, and when he opened them again, he was looking at something I couldn’t see. I tucked the blanket around his knees as if warmth was a message he could carry with him. He took one more breath like a man finishing a good book and not resenting the last page.

The house heard it first. Houses know the difference between footsteps and quiet. A word moved through staff rooms and up stairs and across a lawn that would never again bear marks from a particular set of wheels. We told the children together because families deserve truth in full sentences. Noah stood with his hands in his pockets and pretended to study the carpet and did not fool me. Eli drew the pergola from memory and left it on the chair. Rosie said, “I will sing to him anyway,” and did, because love is not concerned with logistics.

Three days later, the tang of lilies and stipend of relatives. The lawyer read the will in the study where a different kind of sentence had been uttered years ago. Mr. Montgomery had never been a man to do anything small.

He left legacies to charities I recognized from envelopes on his desk. He left money with Helen’s name on it and the instruction for pleasure, not prudence. He left Lucas the vintage motorcycle nobody had been allowed to touch and a note that said, You idiot, learn to ride it first.

Then the lawyer cleared his throat and read the paragraph that makes strangers family.

“To Rachel Whitaker,” he read, “whose courage reminded me I hadn’t used up all the goodness allotted me, I leave the guest house cottage and an operating endowment to create a home-like hospice on this property. People should die where they have been well-loved. If they have not been, they should be loved as if they were. It will be called Orchard Light. She knows why.”

For once in my life I didn’t know what to say. The children looked at me and understood better than words. Lucas grinned like a man who had just watched a map change to include a road he always suspected existed. The lawyer passed me the heavy envelope Mr. Montgomery had mentioned. I took it to the kitchen I love and opened it there because kitchens are where I have learned to meet the truth.

His handwriting had been steady that day. You think I chose you on a whim, it said. I did not. Claire showed me your card from the employment center. I recognized your name from a nurse’s note the night I sat in the hospital while a friend died. Your hands kept her warm while we waited for a body to finish remembering a life. I watched you talk to a stranger as if she were a person you already loved. I decided then that if I was ever lucky enough to die decently, I wanted you in the house.

I sat with the letter until the paper cooled and my heartbeat normalized. He had seen me at my best when I felt at my lowest. Men like him don’t say love easily. He didn’t. He didn’t have to.

We built Orchard Light the way you build anything that lasts: slowly and with consent from the land. The old carriage barn became a place where monitors beeped less and laughter snuck out the windows rudely. Hospice is grief, yes, but it is also praise. We taught the kitchen staff how to make bone broth like a lullaby. We hired nurses who grasped that the real job is not getting pain to zero but getting fear to behave. The orchard became a chapel, the pergola an altar, the path a procession.

People came. They walked in carrying anger or fear or exhaustion or all three. They left—some carried, some walking—with their edges softened by love that did not need them to be anything other than what they were. We didn’t fix dying. We fixed part of living.

Eric tried one more time in a courtroom that had already learned his last name. He asked for money because men who take rarely stop themselves. The judge asked if he had stopped to see his children on the days he had off since August. He said no. The judge said words that belong on stone: Motion denied. He walked out of my life for the final time without turning back. The door did not take offense.

Lucas started falling asleep on the guest house couch on nights when the moon made the orchard glow. He would wake with an apology and a neck kink. One evening I handed him a blanket without comment. He took it and smiled the smile of a man who has decided to move a suitcase without announcing it.

On an anniversary that used to be a day I dreaded, the staff wheeled a new admissions gurney under the pergola. Rosie scattered petals from a basket because that’s what her body told her made sense. Eli hung the sketch he had drawn of the pergola in winter where the morning light could learn it. Noah, taller than my shoulder now, stood next to Lucas and said something that made the older man glare with fondness.

I walked to the edge of the orchard where Mr. Montgomery’s chair used to sit and said thank you to the air. Some people believe ghosts are cold. I do not. The air warmed around my face the way a hand hovers before it touches.

We planted daffodils where his wheels turned the earth. In spring they came up fat and unapologetic.

“Do you ever miss who you were?” Lucas asked one night under stars so numerous it felt like greed.

“I miss believing I had to be small,” I said. “It was easier. But I do not miss me.”

He nodded as if a map had been corrected. “You know,” he said quietly, “you can keep changing here. There’s room.”

“There is,” I said, and didn’t correct you to we because some promises need to finish writing themselves.

When people ask me now what happened—how a postponed life became a beginning—I tell them the shorthand version because truth is heavy and most people are already carrying their own. I say: I answered a phone call. I said yes. A cruel man tried to humiliate me in public and a grumpy widower clapped for a well-placed punch and then went on to save my life by giving me a place to save other people’s. I say: My children grew louder in a house that had been too quiet for years. I say: Love did not so much return as get granted permission.

Sometimes I walk the path to the gate and sit on the low stone wall and watch buses go by. I think about a woman who once stood in a kitchen she had paid for with birthdays and babies and read a letter signed with a man’s exit. I wish I could put a hand through time and touch her cheek and tell her two things:

It’s going to hurt. It’s going to end.

Then I would add, because she will need to hear it twice: It’s going to begin.

I go back to the cottage with windows that remember every version of my children’s laughter and a table that has held grief without complaint and scatter flour with Rosie as if joy were a recipe you measure with your hands. I pour tea and walk it down to the pergola where a new family sits, scared and brave the way all families are when the door between rooms opens. I tell them what someone taught me: “You don’t have to be good at this. You just have to be here.”

And on certain evenings, when the light falls exactly right and the orchard glows like it knows a secret, I catch myself smiling without realizing I’ve started. Not because I won anything in court or survived what I thought I couldn’t, but because I am here—fully. The job I took to keep us fed became the work I was born to do. The man who tried to humble me by leaving taught me to rise by staying. The widower who tested me with insults left me a home and a mission and the sentence that closes every story I now care to tell:

We made a good life out of what was left.

END!

News

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… CH2

To Afford Surgery for My Paralyzed Husband, I Took a Job at a Hotel—But One Day, I Saw Him… …

“Mister, please take my little sister, she’s only six months old and very hungry.” Ethan turned and saw a 7-year-old boy holding a tiny baby close. ch2

The city’s pulse was a frantic drum against Ethan’s ribs. Time was a thief, and it was currently picking his pocket…

The Waitress Said, “My Mother Has the Same Ring.” — The Millionaire Looked at Her and Froze. ch2

Graham Thompson, the 53-year-old founder of Thompson Grand Hotels, sat alone at a corner window table in The Beacon, a warm, wood-paneled…

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… CH2

After My Husband Left On A Business Trip, I Found His Second Phone—I Answered The Call. And… Part One…

My Son’s Family Left Me Stranded on the Highway — So I Sold Their House Without a Second Thought… ch2

Everything began about six months ago, when my son Ethan called me sobbing. “Mom, we’re in trouble,” he choked out,…

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract… CH2

I Was Just the Dishwasher. My Boss Took Me to a Meeting as a Joke—But When I Read the Contract……

End of content

No more pages to load