I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him…

Part One

The emergency room’s fluorescent lights made everything look like it had been soaked in milk: the white tile, the pale-blue curtains, my son’s face as he bit his lip to keep from crying. The cast tech hadn’t arrived yet; the X-rays glowed like comets on the light board, a tiny wrist fractured in two places. My phone buzzed in my palm as I typed with my thumb.

Mark’s in the emergency room. Suspected broken wrist. Can one of you come?

Ten minutes passed. I stared at the blinking cursor as if willing it to morph into my mother’s silhouette, the one who used to stand in doorways and tell us dinner was ready. When her reply finally appeared, the white speech bubble felt like chalk scraping a board.

We’re busy with Margaret’s promotion dinner. Can’t you handle it yourself? He’s probably just being dramatic again.

Dramatic again.

I looked at my son. Ten years old, dirt on his knees from the soccer field, freckles turning to constellations across his nose, arm bent at an angle that refused to make sense. Tears bloomed and vanished in his eyes, the way brave children try to be what they think you need. Something inside me, something that had been bending for thirty-five years to avoid breaking, found the end of its arc and snapped clean.

I stared at the message until my phone screen went dark. Then I reopened it, but not the text thread. My thumb moved to the banking app the way your body moves in a fire drill: trained, efficient, already knowing the exits. Mortgage, car loan, utilities, their credit cards—all the automatic payments I had set up “just for a little while” when my parents insisted they were going to catch up. My name and routing number ghosted across their lives for six years, invisible in conversation but alive on due dates.

One by one, I slid the toggle. Off. Off. Off. Off. I confirmed with my face, with a code, with a quiet that felt like turning off a machine and hearing your house again.

“Mom?” Mark whispered, his uninjured hand creeping to the hem of my cardigan. “Is it going to hurt when they fix it?”

“Yes,” I said, because he has my eyes and can smell lies, “but only for a minute. I’ll be right here.”

My name is Julia. I’m thirty-five, a financial analyst, and until thirty minutes ago, the person who paid for the love that should have been free.

Three days before the cast, before the toggles, before the message that finally told the truth about my family in ten words, I stood in the hallway of my childhood home staring at the wall of photographs that had always felt like a museum dedicated to one person. My sister’s graduation, her wedding, her baby, her second graduation. In each, my mother’s smile was a ribbon being cut at a ceremony; my father’s hand gripped another man’s arm like they’d taken the hill together. Somewhere, in an album, a picture of me with a diploma existed—practical smile, polite relief. It had never made the wall. My promotion photo did not exist because no one had asked to take one.

“Julia, is that you? Come help me with the dishes,” my mother called from the kitchen, as if speaking across a summer afternoon when we were seven and nine and had not yet learned that love could be rationed.

I had not come to do dishes. I had come to stop behaving like a daughter signing up for extra shifts at a job that paid in disappointment. But bodies move along old grooves; I found myself in front of a cutting board stacking sesame crackers into a fan while my mother wiped her hands on the dish towel I bought her last Christmas.

“Margaret likes sesame,” she said, sliding the plain ones aside as if they were a mistake she’d forgive only once. “Not plain.”

My phone buzzed. Did you tell them yet? It was from Sharon, my ex-mother-in-law, the woman who had shown up at a hospital with a bag and a casserole when my appendix tried to ruin everything. She had been more family across seven years of my marriage and three years of my divorce than my parents had been my whole life. Tell them you’re done. Tell them you’re not a bank.

I hadn’t told them. It turns out there’s no good time to inform your parents you will no longer be their lender of last resort. It turns out there is only doing it and then discovering who they are without your balance due.

The front door opened, banged against the stopper, and my father’s steps came down the hall like a drumline. “Where’s your mother?” he asked the air, his eyes sliding past me as if I were a shadow that sometimes cooked. “Margaret’s due any minute.”

“She’s getting ready,” I said. “She asked me to…”

He nodded and vanished toward the living room where football and men made a single sound.

When my mother returned wearing the blouse I’d picked out at a December sale so she’d have something nice that fit, I slid the arranged tray toward her and said, “We need to talk.”

Her face shifted from party to storm. “About what? Can it wait until after—”

“I’m stopping all financial support,” I said, and watched her blanch with a double exposure: this day and every day I had kept my mouth shut because it seemed easier for everyone if I swallowed.

“What financial support?” she asked. There are two kinds of people in this world: those who genuinely forget who pays, and those who prefer to ask you to say it so they can resent the sound.

“The car loan. The credit cards. The house insurance. The utilities. The mortgage when it was short.” I kept my voice level the way you keep your hand level when you’re measuring flour and everyone’s watching to see if you’ll be generous.

“After everything we’ve done for you,” she said, and it would have made me laugh if it didn’t make me want to throw the crackers into the sink. I did laugh, a short sound I didn’t recognize as mine.

“What exactly have you done for me?” I asked. “Besides raise me in a house with your favorite child and ask me to cover your bills afterward?”

“We raised you,” my father said from the doorway, not having heard the beginnings but sure of his role in every ending. He looked at me like something unpleasant in the oven had started to smoke. “We made sure you had food to eat.”

“That’s the bare minimum,” I said, and my voice was a thing I had not used in this house: it did not pitch up at the end, it did not apologize with its choice of word. “When Randy left, who helped me? When I was doubled over and texting you from an ER because my appendix was trying to kill me, who picked up your grandson? When I got promoted, who sent a text? Sharon did. Brian did. My ex-husband’s parents.”

My mother’s mouth pressed into a white line. “We couldn’t leave Margaret’s dinner,” she said, digging in the drawer where she keeps justifications. “She would have been upset if we’d missed it.”

“More upset than your daughter being wheeled into surgery?” I asked. “More upset than Mark being called a burden because he eats?” The memory of that sentence—a quiet murmur, as if the word burden were a private joke—hit me like a second shot. “He’s just so much work,” my mother had said, considering an entrée menu and my child, and there is no apology I know that can undo that sentence once it exists.

At that moment Margaret breezed in, perfume wafting, joy whipping her hair around her shoulders like a flag. “Mom! Dad! I brought champagne!” She stopped when she saw me. “Jules? Are you—what…? Are you staying?”

“I came to set a boundary,” I said. “And to tell you all congratulations on your promotion.” I found my keys in my purse with the cool logic of a surgeon who knows sulking is the least effective treatment for anything.

“Julia, wait,” my mother said, and for the first time in my life she sounded like someone who had misjudged a recipe and did not know which thing she could add to fix it.

“I am done,” I said. “You used me when it was convenient and you ignore me when it’s not. You don’t get me and my money, not anymore.”

I walked out as the oven timer dinged. On the porch, I heard my father say, “It’s not that serious,” and my mother say, “What will we tell people?” and Margaret whisper, “What happened?” while champagne popped like celebratory gunshots.

In the car, I cried and then didn’t, and then looked at my phone. My ex-husband’s mother had sent a photo: Mark with flour on his cheeks and a noodle hung over each ear, laughing the way you laugh when the world around you is someone else’s problem.

Sometimes you do not realize how starved you are for a different story until you take a bite.

Three days later, when the cast was still fresh and Mark was rubbing at the itchy part with a pencil eraser, my phone lit with a call from my mother. I had blocked her number after the ER text; she called from my father’s phone instead, a trick older than me.

“We need to talk about this situation,” she said without hello.

“What situation?” I asked. There are two kinds of conversations in this world: those that begin with I’m sorry and those that begin with we need to talk about.

“Your decision to… to cut off support. The mortgage is due. Your father’s medication—”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said, and left it at that, because there is a place inside you that opens when you finally realize someone else’s emergency is not yours.

“You can’t just leave us like this. We’re your parents,” she said, and it was almost endearing, how quickly she toggled between you’re nothing and you owe us everything.

“Blood is not a debit card,” I said. “You didn’t choose me then. I am choosing me now.”

She went from pleading to bitter to what she always becomes under pressure: cruel. “You’re doing this because we didn’t come hold your hand for a little sprain. Mark is dramatic, Julia. He gets that from you.”

“His arm was broken,” I said, and felt the weight of years settle into the back of my throat, as if every time I’d swallowed a retort had calcified into a vertebra that now, finally, let me stand. “Don’t call this number again.” I hung up and blocked that line, too. Two numbers silenced, which in this house counts as progress.

Mark looked up from the kitchen table where his family tree project had sprouted across poster board and glue. He had drawn Sharon and Brian’s faces into the branches without an eraser in sight. My name, his name, a dog whose lineage we do not know. No Margaret. No my parents.

“Is this everyone in our family?” I asked.

He nodded, pen cap in his mouth, perfectly confident. “These are the ones who love us.”

Simple. True. Floor plan of a house I wanted to keep.

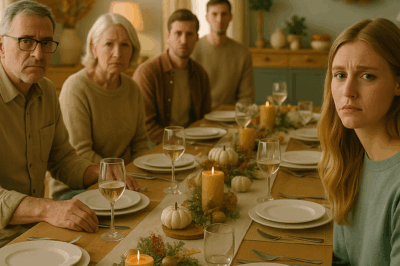

The universe, which has a sense of humor and an impeccable sense of scheduling, arranged for Thanksgiving two weeks after the ER. It arranged, too, for all the orders my mother had placed under my name at the butcher and bakery to be cancelled and refunded and for my father’s call to arrive at 12:17 p.m. with hushed chaos in the background.

“The food never arrived,” he said, and his voice cracked at the end of the sentence the way voices crack when self-image meets evidence.

“Oh,” I said. “I didn’t think you needed anything from me.”

There are sentences that fit so exactly in the hollow they were shaped for that you can hear the click. The silence after this one was cathedral-sized. Somewhere behind my father, my mother said, “What does she mean?” and somewhere to the left an aunt who loves me and cannot fix any of this whispered to someone else, “She means what she said.”

“You embarrassed your mother,” my father said three days later, when he had found his righteous footing again.

“She embarrassed herself,” I said. “I simply left her alone with it.”

For Christmas I drove to my parents’ house on time and uninvited. My grandmother—my mother’s mother, the one my mother had fallen out with for a decade over a story that changes each time she tells it—got out of my passenger seat wearing a hat like a weapon. When she stepped into the foyer, my mother made a noise like a porcelain doll tipping over.

“Oh my,” Grandma said, looking around. “It’s been so long since I’ve been in the house I paid the down payment on.”

Christmas dinner was a theater with a happy audience and a cast trying to remember their lines. My grandmother picked up a spoonful of stuffing and said, “Store-bought?” and my sister choked. After the pie, in the kitchen where girls have always had to find their sharpest sentences, my mother said, “You’re trying to humiliate me,” and my grandmother said, “You did that all by yourself.”

Two weeks later, the phone calls started again. This time my father’s voice was smaller. “Your mother tells people you’re unstable,” he said, in the tone of a man who will sit with you on a porch and pretend that acknowledging the weather makes him a meteorologist.

“She’s telling people I’m having a breakdown because it’s easier than saying she is wrong,” I said. “People who know me know it isn’t true. People who know her know that it is.”

“Christmas,” he said weakly. “You made a spectacle.”

“You made an example,” I corrected. “I decided to be the lesson.”

My brother, who is neither blameless nor a villain, texted at 9:13 p.m. on a Thursday. Hey. Coffee? I almost wrote for you or Mom, but didn’t, because not every kindness is an errand. At the cafe, he stared into a latte like the answer was in the foam and said, “I think I’ve been a coward.” He said it before I could do the thing I normally do: take it on so he didn’t have to.

“She says you’re cruel,” he added after a minute. “I think you’re… consistent. And Mom’s angry because she can’t use you anymore.”

It was the first time he’d drafted a sentence without her approval. “This doesn’t mean I’ll come to bat every time you two fight,” I said, and he smiled like he’d expected me to and had prepared to say it himself if I didn’t.

“Good,” he said. “I need to stop asking women to run interference for me.”

By March, the calls had turned into letters, the letters into silence. My sister phoned once to say, “They expect me to cover the mortgage,” and I said, “You’re the favorite,” and we didn’t laugh, because for the first time the word didn’t feel like a crown; it felt like a bill. “Good for you,” she said softly when we hung up. It was the nicest thing she had said to me in years. Niceness matters when it begins at truth.

There were practical consequences. They lost the car because the bank does not care if people like you, only if you pay them. The mortgage fell behind; my father called the bank and remembered why he’d liked having me as his customer service department. My mother appealed to the court of public opinion; the jury yawned. It turns out people can watch you push a daughter off a calendar and then send you a casserole when you say she’s unstable, but they won’t bake for you when your daughter quietly texts the family group chat, Happy New Year, I’m fine, and refuses to be the villain in your story.

I built new traditions with the people who had earned the right to hand me a spoon. Sunday dinners at Sharon and Brian’s became sacrosanct. Mark learned to braid pasta, to stir slowly, to set three extra places because “you never know who will show up hungry.” He broke one glass and no one said “burden.” Sharon bought him a step stool so he could see the stovetop and a notebook so he could write down recipes, and on the first page he wrote SPAGHETTI BECAUSE LOVE, and that is the gospel.

In May, his school held a family day at the park. At the picnic table, kids introduced their grandparents to their teachers. Mark ran to Sharon and Brian and dragged them toward his soccer coach, breathless. “These are my grandparents,” he said, the simplicity of the sentence a small revolution. Sharon shook the coach’s hand and told him Mark had been practicing with a broom in the hallway because of his cast. “He’s passionate,” she said, and there is no stronger spell than hearing a thing you thought was a liability reframed as a gift.

We passed my parents on the way to the car. They were standing with my sister under a maple tree, the leaves making polka dots on their faces. My mother looked at me the way people look at an old injury when it aches before a storm. “Julia,” she said. My name, nothing more. She held her purse like a question. Her eyes dropped to Mark’s cast—now covered in signatures and drawings and a scribble that looks like love—and she said, “Does it itch?”

“It does,” Mark said solemnly, as if she had asked the most important question of his life. She laughed, startled. For a second, the world was a kitchen in 1989 and she was learning to be a person who asks how children are and not a person who tells them to lower their voices. “Don’t put anything down there,” she added, and then glanced at me like she didn’t trust herself to add sorry and certainly didn’t know how to add thank you for not letting me use you anymore.

“We should go,” I said, because boundaries don’t enforce themselves. We walked away and she didn’t call my name twice. That counts as mercy.

Six months after the ER, after Thanksgiving, after Christmas with a hat and a grandmother, I sat on my back steps with a glass of pinot and watched fireflies invent a language. Mark had fallen asleep on the couch with a library book about planets open on his chest. Across the street, our neighbor watered a patch of grass that insists on being brown. The city hummed a safe distance away. My phone buzzed with a text from Sharon: Chili’s on Sunday. Brian says bring appetites and that weird salad you make with the lemon thing.

Wouldn’t miss it, I typed back.

There was a time when I would have tried to fix it all. I would have bought the turkey, made the pie, hand-delivered the apology my mother needed me to perform on her behalf to her friends. I would have pulled one more night shift at the bank of my own heart.

Here is the end you asked for when you read the beginning and felt your stomach clench because you know exactly what it means to be told your child is dramatic again and your grief is inconvenient and your money is expected: it is not the end where my mother falls at my feet or the one where my father weeps into a hankie and says everything he should have said at seventeen. It is the end where I am okay. It is the end where my son knows exactly who shows up when he breaks and exactly who calls him brave. It is the end where a family tree has branches that grow in directions genetics would never predict.

It is the end where I pay for nothing I don’t want and everything I do. It is the end where my ribcage finally stops feeling like a cage and starts feeling like a porch I built with my own money and my own rules.

Part Two

The ER’s wrist-care pamphlet migrated to the refrigerator by sheer gravity. It sat there among a zoo of magnetized pizza coupons and a crooked drawing of a Star Destroyer from Star Wars because Mark insists that villains should get displayed sometimes, too. Life found a new tempo: school drop-offs, two-person dinners at a kitchen table with one wobbly leg, spreadsheets at midnight after Mark fell asleep and the wineglass was only water. The months stretched and then snapped back like a rubber band you’ve forgotten is around your wrist.

My mother didn’t call again. My father did, twice, and both times hung up when it went to voicemail, maybe spooked by the recorded version of me reminding him that boundaries weren’t a phase. My sister sent one text mid-February to ask if I knew my parents’ mortgage servicer would allow a grace period. “They thought you might know,” she wrote, which is the closest anyone in my family has come to the sentence you are valuable. I wrote back: There are hardship programs. They can call. I didn’t add: They can do hard things without me. It was implied.

On a Sunday night in March, Grandma called at exactly the time she calls because she is a woman who trusts clocks. “Your mother brought me to the doctor today,” she announced without preamble.

I sat up. “Voluntarily?”

“Apparently she’s discovered I am eighty-two,” Grandma said dryly. “She is practicing. She apologized to Dr. Kumar for being, and I quote, ‘a real piece of work’ at my last appointment.”

I laughed. “Is hell currently experiencing a breeze?”

“Drafty,” Grandma said. “And listen. She said the words to me: ‘I told lies about my own child.’”

My breath did something painful. “Did she say why?”

“She said,” Grandma continued, and I could hear her papers rustle as if she were reading from notes, “that when you left the game, she didn’t know how to explain that you had never been given a fair shot. She said she was embarrassed because her friends ask about children as if motherhood were a scoreboard.”

I let the quiet stretch until it could hold more things. “Did she ask you to tell me?”

“She asked me to tell you she’s seeing a counselor,” Grandma said, and then after a beat, “I think she meant it. I know when people mean things. I am old.”

I didn’t call my mother. I didn’t text. I sat with the information like a stone in my pocket and didn’t try to skip it across any water. People either change or they don’t. Your participation has little to do with it beyond removing the cushions you make for their falls.

The call from my father came in April. Saturday. Yard work hour in a suburban time zone. “I’m at the car dealership,” he said, as if he were calling to tell me the weather. “We’re getting a used Corolla.”

“Good car,” I said.

“We liked the SUV,” he continued, “but it’s too much. We…” He cleared his throat, a sound like a man swallowing a rock. “We’re adjusting.”

There are words your father says late to you that still land on time for your child. “I’m glad,” I said. “Mark will think it’s funny that you’ll have the same car as his soccer coach.”

“Tell him…” My father paused, as if the next words were behind a heavy door. “Tell him Grandpa says he was brave,” he said, a half-step behind the moment you wanted but acceptable, nonetheless.

I did. Mark nodded and asked if Grandpa knew about the biomechanics of wrist casts, which he had researched for a school presentation because he is, for better and worse, mine.

Two weeks after my father’s call, my sister knocked on my door on a Tuesday, holding paper grocery bags and a bouquet of chrysanthemums that had seen better days. “Peace offering,” she said, grimacing. “They were on sale, and I forgot flowers are supposed to look like they haven’t suffered.”

I grinned and made room on the counter. She stacked pasta, canned tomatoes, and three kinds of chips with the reverence of a pilgrim. “I started therapy,” she blurted. “Mom gave me her therapist’s card. We’re talking about favorite children and scapegoats and all the fun words.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I meant both that you were chosen without consent and that you missed out on the part where you get to be complicated without being punished.

“It’s weird,” Margaret said. “Apparently constantly being the favorite makes you a liar. I learned to say what kept me safe. It turned me into someone I don’t always like.”

We made spaghetti in companionable silence, in the kitchen of my house where girls talk like people, not like resumes, and then we ate it on the rug with bowls because sometimes the act of moving furniture keeps old ghosts from sitting in chairs.

“Do you hate me?” she asked around the last meatball.

“Sometimes,” I said, because truth is a hobby I recommend, “in the past. But mostly I hate the way we were cast in a play we didn’t audition for.”

Margaret breathed out like a tire releasing air after a long drive. “Do you think Mom can be… different?”

“I think people can be,” I said. “I think you can be. I think I can be.” I didn’t add and I think my boy already is because that part is a prayer and we do not say those out loud if we want them answered.

We cooked with my grandmother the following Sunday: three generations rolling meatballs, four hands, one recipe scribbled on a card that says handful where it should say teaspoon because love, like old ladies, does not measure the way new books do. My mother arrived late, carrying a salad that was mostly lettuce but also, clearly, an offering. She hugged Mark and didn’t squeeze him the way people do to extract compliance. She stood next to me at the stove and said, “I told Aunt Patricia the truth and she said, ‘well, finally’ and then she cried.”

“Patricia loves crying,” Grandma said. “She used to cry at The Price Is Right.”

“I’m trying,” my mother said, and the word trying made me drop a spoon because I have been a mother and I know what it takes to put that verb in your mouth. She glanced at me and looked afraid and then held it. “I told my book club that I taught you to cook everything and you taught yourself to feed yourself in better ways than I did. I told them I was mean. It felt like… something broke.”

“Plates break,” Grandma said, handing her a dish towel. “We have more.”

We ate in a house that had my mother in it, a version I had never met because she had never introduced us, a woman who could say she had been wrong in a room that had once been an altar to her certainty. When we cleared the dishes, my mother tried to sweep around my feet like she always does—fixing, hovering—but then she stopped and said, “Teach me the boundary thing.”

“It’s not magic,” I said. “It’s just deciding what you will and won’t do and then behaving accordingly—over and over until it becomes a story other people have to include when they tell yours.”

“Over and over,” she echoed. “Like mass,” she added, because she can’t help but make everything a sacrament.

“Exactly,” I said, and Grandma rolled her eyes and told us to stop being poets and start being dishwashers.

The call from the school came in May. Not an emergency, not a nurse saying “he’s fine,” not another wrist trying to escape the arm. “Family night,” Ms. Garza, the counselor, said. “We’re hosting a workshop on family systems. It might be useful.”

I laughed because my picture is in the dictionary under boundaries, but I went because my child goes to a school where they still believe community is possible. The workshop was taught by a woman with a voice like a whetstone—slowly sharpening everything it touched. She put a diagram on a whiteboard: scapegoat here, golden child there, lost child floating at the margins. Parents nodded as if someone had finally named why Thanksgiving makes their teeth hurt.

“Breaking cycles,” the counselor said, “looks like telling your mother ‘no’ in a gentle voice until she learns how to love you without conditions. It looks like telling your child ‘I’m sorry’ and meaning it. It looks like loving your parents from across the street and leaving casseroles on the porch if necessary.”

Afterward, my mother walked me to my car. “I didn’t know I could say sorry,” she said. “We weren’t allowed to. It meant you lost.”

“Winning is expensive,” I said.

“I’m tired,” she said, and she didn’t mean from the workshop.

“You can rest,” I said. There are sentences only daughters can offer their mothers. She took it, slowly, like soup you’re not sure you deserve.

Mark’s cast came off in June. The doctor cut the plaster with a tool that sounded like it wanted to be dangerous but wasn’t. “Don’t be scared,” he told Mark, and Mark nodded like a very small politician acknowledging a very large crowd. When the cast fell away, his arm was pale and hairless, a new creature under a rock. He flexed it. “It feels light,” he said, amazed.

“Look at you,” Sharon said, clapping. “Now you can stir again without injuring someone.”

“Grandma Sharon,” Mark said in the car, rolling the window down and closing his eyes to feel air on skin that hadn’t felt it in six weeks, “are we still a family when we’re not cooking?”

“Of course we are,” she said. “We’re a family when we’re yelling and when we’re quiet and when we’re stirring and when we’re washing and when we’re reading and when we’re absolutely sick of each other and when we’re not.”

“Even when Mom says no to her mom?” he asked, the way children ask if gravity applies to them too.

“Especially then,” Sharon said, and I squeezed the steering wheel a little too hard because it was a sentence my own mother could not have formed until recently.

In July, we went to the lake in a rental car that didn’t feel like debt. My father taught Mark how to skip stones, which is the only religion I practice consistently. “It’s about flatness,” he said, showing him how to choose and hold. “It’s about angle and wrist and pretending you control the water when you know you don’t.”

“Like life,” Grandma muttered from a folding chair, catching the sun with a visor that has seen fifty summers.

“You were right,” I said to my father quietly, because some places are holy and honesty is how you thank them. “Stones stay. Rivers move.”

He nodded. “I said that?” he asked, who has said more hurt than help and is surprised a good thing made it through.

“You did,” I said. “And anyway, it’s true.”

We watched Mark send one, two, three clear bounces out into soft water. He grinned like a magic trick had chosen him. My mother watched him and then pulled the brim of her hat down, and I think there were tears in the shade where her eyes live now.

There are endings that disappoint because nothing explodes. You think you want fireworks; turns out you want peace with a soundtrack of crickets. Here is the end where my mother does not become a saint but becomes a person with a calendar that sometimes includes therapy. Here is the end where my father admits things he cannot fix and buys a car he can. Here is the end where my sister learns to be a sister in the middle of her life and we forgive the girl neither of us got to be.

Here is the end where I do not go broke buying love; I invest in safety and spaghetti instead. Here is the end where Mark learns the difference between people who say we’re busy and people who show up with a bag and say we brought cards in case we have to wait. Here is the end where Thanksgiving is a table that fits exactly enough and the turkey arrives because the person expected to bring it was invited and because if they weren’t, someone would make soup and we’d call it providence.

Here is the end where I sit on a back step under a sky that does not ask me to prove anything anymore and I am grateful, not because my mother has changed in a way that erases the ways she didn’t, but because I have. Because I did the thing you are not supposed to do in families like mine: I told a story with a different ending and then lived in it long enough that other people had to acknowledge the address. Because my son will grow up inside a narrative where love does not require a receipt.

On Sunday, Sharon texted: Mark says we need garlic bread. Bring your appetite. I sent back a photo of the loaf rising on my counter and the word Always.

After dinner, Mark carried plates to the sink without being asked and looked at me with pasta on his chin like the happiest thing in the world is knowing what to do. He was right. He is often right. I wiped his chin with a dish towel and kissed the top of his head and thought, this is how cycles end: not with a courtroom speech, but with a child who believes showing up is normal and love is not a line item and family is a verb.

When we left, Brian called after us from the porch: “Drive safe, and text when you get home, okay?”

I texted my grandmother when we did. She responded with a single emoji I have taught her to use correctly: the heart that doesn’t beat but still feels somehow alive. My mother sent a message too, not complicated, not manipulative—I made chili. Do you want the recipe?—and I thought, look at that: women teaching other women to feed themselves.

I didn’t think to check my banking app on the way upstairs because I don’t do that anymore. The toggles stayed off. The lights stayed on. The quiet inside my chest felt earned. And when I fell asleep, I did not dream of emergency rooms or text bubbles or calendars with my name erased. I dreamed of a lake and a small boy with a strong arm and a stone skipping toward a center he didn’t have to reach to prove he could.

END!

News

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead. CH2

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead Part…

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

End of content

No more pages to load