Part 1

It was late September when I came home.

The sun was angling low through the sugar maples on our street, gilding the edges of every picket fence. The air held that thin, clean chill it always gets when summer lets go for real. I walked up the front path, duffel bumping my hip, a skitter of dry leaves chasing my heels, and knocked because that’s what you do when you’ve been gone awhile, even if it’s your own house.

Mom opened the door. For a second, the light behind her was too bright and her face was too much shadow. Then she pulled me into focus the way a person does with a name they haven’t said in a while.

“M—Max… you’re home?” she said, like it hurt.

She came toward me slowly, looking me up and down, and then dropped to her knees and hugged me. I felt the breath punch out of her like the last air from a beach ball. Over her shoulder, I saw Dad standing in the den doorway. He didn’t say anything. His hand went out and found the doorknob, like it had been waiting there for it, and then he turned and shut himself inside. The click of the lock was a statement. He’d always been a man who thought doors were sentences.

He was probably still angry with me. Before camp, I broke into his gun cabinet with some friends from school. Benny—you’d like Benny, if you like people who set the room on fire and then grin at you like they’ve invented warmth—pulled a trigger without meaning to. The bullet punched a hole in the den wall, a neat black mouth ringed by plaster dust. No one got hurt, unless you count my next three days.

“Do you have any idea how stupid that was?” Dad had said, his voice like a belt being pulled through loops. “You’re extremely lucky no one was hurt.”

“I’d ground you,” he’d added, the words clipping, “but I’m just glad you’ll be out of my sight for the next two months.”

He’d kicked me out of the den and sent me to my room without dinner. I wasn’t hungry anyway. Rage is a full meal.

Later, there was a knock at my door, soft as a secret. I opened it and Ryleigh stood there with a plate of food. She pressed it into my chest like she was pinning a medal on me.

“Mom said to sneak you a plate,” she said.

She is taller than me. Big hair. Bigger mouth. Jean jacket vest over a Black Sabbath tee, necklaces like she’d mugged a street vendor and kept the spoils. The smell of hairspray came off her like a threat. Her eyeliner could cut glass. She was sixteen turning seventeen and it made her walk like she owed the house nothing.

“You going out?” I asked.

“No, twerp,” she said. “I dress this way and put on war paint before I go to la‑la land.”

“Do Mom and Dad know?”

“They don’t, and you better not tell them either.” She leaned in. “Or I’ll tell Mom about your noody mags, you little perv.”

She had me dead to rights. Benny had slipped me two magazines during class and I kept them inside a geometry book like irony. I nodded. She smirked and tapped the plate. “Eat. I spit in the broccoli.”

Later, after the house yawned and went to sleep, I heard her window lift and her sneaker soles squeak against the gutter. The next morning, pancakes, eggs, bacon—weekend trinity. Dad sat at the table with his coffee and his paper, still on his first cup, which meant he was an animal who might bite. He never said anything to anyone until his second cup. That day he was extra silent. Hatred of Benny radiated off him in little waves like heat off a hood.

Ryleigh didn’t come down for breakfast. I didn’t expect her. The day wore itself gray, then brightened again toward afternoon. I watched cartoons on the couch, too old for them, but not if the volume was low enough. At 2:14 p.m., a bus pulled up in front of the house with Camp Mannatari spiked on the side in cheery blue paint. The driver’s hat sat at an angle that said he did not think the paint was cheery.

I hugged Ryleigh. Mom kissed the top of my head. Dad stood there like a door in a hallway and didn’t shake my hand like he usually does when I go away for longer than a weekend. He looked at me the way he looked at thunderstorms—like they were personal.

“It’ll be good for you,” Mom said.

She said that about vegetables and church and cleaning my room and orthodontists and now a campground four hours away in a town with a name that sounded like a lullaby someone wrote to sell in a tourist shop.

Sleepy Falls was smaller than I’d imagined, and somehow bigger. The bus snaked through the market district, which was one street with a bend in it, posted with hand‑painted signs for antiques and fresh pies and bait. People came out to watch us pass. They didn’t wave. They didn’t smile. Faces have a way of looking blank when they’re watching things leave. When the bus reached the trees, it kept going, and then kept going, and then kept going. The forest pulled us in with a dozen quiet hands.

Camp Mannatari had everything a brochure promises: a lake wiped clean and set in a picture frame of pines; boats like teeth along the dock; a go‑kart track chalk‑scarred with skid marks; tables for crafts that looked like splinters waiting to happen; an archery range fenced off like it was about to be embarrassed by us; garden rows slick with hose water; a trailhead marked with a carved post and a cartoon fox with its paw to its lips, telling us to be quiet.

They put me in Bunkhouse Three. The counselors smiled too much. Maybe that’s part of the uniform, like the lanyards. Ms. Keen had a smile that didn’t make me suspicious. She was young, maybe nineteen, red hair pulled into a ponytail, freckles like someone had sprinkled nutmeg on her. She looked like the kind of person who knows how to fold a map and who actually uses sunscreen.

On the fourth night, we sat around a fire and the counselors told us stories. The ones that start like A long time ago and end like a dare not to look over your shoulder. Someone asked about the camp’s name.

Ms. Keen glanced at her co‑counselor, who did the weary shrug of a guy not excited to be the one to say the word Mannatari out loud near children. She told the story instead.

“European settlers came in the fifteenth century,” she said. “There were already stories here about a guardian in the woods. A watcher. The Mannatari.” She said the name without italics. “It took those who wandered, they say. Or protected them from worse. It depends who tells it. Some say fae, some say spirit. Names are nets. Sometimes they’re holes.”

I raised my hand. It seemed like the thing to do if you were going to say a thing.

“Yes—Max, right?” she said, pointing at me with the kind of accuracy that means she actually learned our names and didn’t just read them off a clipboard.

“Why would they name a camp after a monster?” I asked.

“I think,” she said, and glanced at the trees as if they’d correct her grammar if she got something wrong, “that someone once figured the best way to make a thing less scary is to put it on a T‑shirt.”

The kids buzzed, pleased to be outside at night being told to be scared on purpose. Ms. Keen leaned forward, elbows on her knees. “How about the Horseman from Hell?”

If that story had a point, I don’t remember. My eyeballs were busy drinking firelight off other faces, looking for shapes in the dark space between tree trunks, thinking about Ms. Keen’s voice, the way it bent around certain syllables like she was making sure she didn’t snag them on anything sharp.

Camp is built to be forgettable in the ways parents want it to be. Days stacked up: lake, crafts, archery, lunch, garden, go‑karts, back to lake. We hiked the same loop so often that the trees started to feel like wallpaper. I found my favorite knot in a birch that looked like an eye squinting. I learned which plank on the dock had a nail that would snag your sleeve. I registered that the counselors looked different when they thought no one was watching. Tighter around the mouth. Counting heads more often than they meant to. Ms. Keen got sick.

At first it was the kind of sick that makes you wave and laugh and say go to bed like a joke. Then she stayed in her bunkhouse with the blinds slatted and we could see her sometimes, watching us play like a person at a window seat in a train that will never stop at the right station. Then the blinds stayed down. I asked a counselor where she was.

“Oh, Ms. Keen?” He said it like he was looking for the page in a manual. “We had to send her to the hospital. She was really sick and not getting any better.”

“Will she be back before the end of camp?”

“N—no… m—maybe next year.” He shifted his clipboard in his hands and folded one corner over. “Hey, no more questions. Let’s get ready for one of our last nature hikes.”

He said last like it was supposed to make us savor it. It made my stomach feel like a pocket with a hole.

We walked the trail we always walked. I dragged my feet a little because when you’re leaving a place, every step can be sabotage. The trees did their tree thing. The underbrush made that underbrush sound Mother Nature loves. I fell behind without meaning to. The others rounded a bend and the path made a small hush like it was remembering a secret.

“Mah… Mah… Max,” someone said, soft and wrong.

I stopped. The hair on my arms stood up so fast it almost made a noise.

“Mah—Max.”

“Ms. Keen?” I said, turning in a circle as if the word would point.

“P—please help me… Y—you don’t have to do this,” she said. Her voice was a record played at the wrong speed. “P—please follow me, children.”

“Guys!” I shouted, stupid, brave, both. “Hey, I found Ms. Keen! I think she’s hurt!”

The loop of the path in front of me did not answer. The wind didn’t carry my voice forward like it is supposed to in stories. I stepped off the trail the way you step off a curb you didn’t see. I followed the sound into the trees, then deeper, then deeper, and then I was somewhere that looked like the place I’d been but the angle of everything had changed and the light had a different grammar.

I’ve tried since then to tell myself I was only lost for an hour. The sun disagrees with me. The ground under my shoes remembers a longer weight. My body—my body remembers the in‑between feeling. The thing where you are a noun with bad adjectives. Hungry, thirsty, scared. I found the path again because paths want to be found. They’re vain. I followed it backward to a place that pretended it was the place I left. The camp was still there when I broke out of the trees like a swimmer reaching a dock he wasn’t sure he’d make. The sky was the wrong color for the time I thought it should be. People were nowhere. Doors were shut politely.

When I reached home, I thought I should feel relief like a puddle you step into. I did, and then it ran out through a crack I didn’t know was there.

Mom’s hug had heat like a fever. She pressed her face into my shoulder and made a sound I didn’t know she could make, a sound like someone tearing a shirt slowly. Dad’s door closed like an apology written in block letters. Ryleigh thundered down the stairs, half makeup, Black Sabbath, hair that had recently known wind, and stopped in the doorway.

“What the fuck happened?” she said, and then she saw me. She saw all of me at once, the way a person does when they’ve been thinking about you in the past tense.

“R—Ryleigh,” I said. The way the name came out of my mouth felt like trying on a shirt and not liking where the seams hit. Mom let go like she’d been pushed and went to her hands and knees and cried into the tile like the tile had personally wronged her.

From the den, a sound: pop. Not loud. Not not loud. A sound a house knows what to do with. The thick, muffled sound that doesn’t bounce off walls because it sinks into them. The kind of sound that makes your bones think you’ve fallen down a step you forgot was there.

I looked at the den door. So did Ryleigh. She had a look I didn’t have a word for. The nearest word was inventory, as if she was counting things she was about to lose.

“What the fuck?!” she screamed, and bolted back up the stairs and slammed her door so hard the house sneezed.

I went to the kitchen wall phone because a person should do a thing. The cord curled like a stolen tail. I picked up. The line was open. I could hear someone breathing ragged, trying not to show it to whoever else might be listening.

“911, what is your emergency?” a woman said, ready and bored and kind.

Ryleigh’s voice came through, too loud and too small. “Hello? Please send help! I’m at 3232 W. Holly Lane.”

“What is happening there?”

“It’s my brother. He’s downstairs with my mother. I think my father shot himself.”

There was the smallest pause, the size of a blink. “Your father shot himself. Okay. We’ll send a cruiser and an ambulance your way.”

“No,” she said, and her voice broke on it. “That’s not it. My brother disappeared a month ago at summer camp. They found his body in the woods. We buried him last week.” She made a sound like a laugh that had misfired and become a sob. “That thing downstairs is not my brother.”

Her voice fell apart then, all at once, like a bridge that finally drops after the last suspension cable snaps. The operator said something, calm and steady, the way the ocean talks to the shore even when a storm has knocked a boat loose, but the words blurred. I hung the phone back on its cradle with the care you use for a sleeping animal you hope won’t wake up.

Footsteps on the sidewalk. Sirens in the wrong distance, then closer, then too close, then cut. Blue flashes strobed through the front windows, painting the living room in a police heartbeat. A neighbor’s front door opened across the street and the neighbor stood in his socks on the top step, mouth slightly open, trying to portion out how much of this was his business.

The first cop in the door had the kind of mustache that thinks it does more work than it does. He kept his hand near his belt like it was a conversation he needed to keep going. His partner scanned the room like her eyes were a scanner that could print answers if you fed them paper. She looked at me, then at Mom on her knees, then at the den door.

“Sir?” the mustache said, because sometimes boys are sir when a cop needs them to be. “Can you step away from the door?”

I did. My legs moved like they were listening to a song no one else could hear. They guided me to the couch and folded me into it. Mom made a sound that was gone as soon as it was anywhere. The woman cop crouched beside her. “Ma’am,” she said softly, the way you say someone’s name first when you need them to find it. “Ma’am, I’m Officer Ramirez. Can you look at me?”

A paramedic with a soft belly and hard hands went into the den with the mustache cop. There was a word said quietly in there—clear—in the tone a person uses when they’ve done this before and will do it again. There was the rustle of something expensive being used for the thing it’s meant for. There was silence.

Ramirez shifted and looked up toward the stairs. “Ryleigh?” she called.

The upstairs hall spit out my sister. Her face was a map drawn by someone who didn’t want anyone else to use it. She came down, step by step, looking at the cops, at Mom, at me last. She stopped two steps from the bottom and held there, like the floor below was a lie.

“Hey,” the mustache cop said from the den doorway, and all the soft in the room swallowed itself. He didn’t have to say anything else. The shape behind him—the fact of it—did the talking he didn’t want to do.

Ryleigh’s breath hitched once. “That’s not my brother,” she said, and her eyes were on me and through me, wide and wet and not blinking. “I don’t know what that is, but it’s not Max.”

She wasn’t wrong. Or she was. Or those things were the same.

The paramedic came out and shut the den door again the way you set a lid on a pot that will never need to be opened. He put a hand on the mustache cop’s shoulder. The cop swallowed. His Adam’s apple slid like a trapped fish.

I looked at my hands. The lines there. The turf burn scar near my thumb from falling off my bike when I was eight. The spot of paint on my index finger where I’d been touching up the baseboards in June and claimed I would finish later and didn’t. They were my hands.

Mom reached for me without looking up, grabbed a fistful of my jeans, and held on like she had fallen off a cliff and I was the root sticking out of the dirt. I put my palm on her hair because I couldn’t think of anything else to do. It was softer than I’d noticed my whole life.

When the coroner came, he did it like a man carrying a laundry basket, no ceremony, all function, and somehow that was mercy. He was an old friend of Dad’s, or at least someone who had once borrowed a wrench from him, judging by the way he said my last name with a sigh. The body bag was quieter than I thought it would be. The zipper made its zipper noise anyway. Ryleigh made a sound like a bottle breaking in another room. The sound broke nothing you could sweep up.

Ramirez asked me questions that didn’t feel like questions. Had I seen Dad? Had I talked to him? Did I hear a fight? Had he been depressed? Had he been drinking? Had he ever said anything? Did he own any other weapons? Did anyone else have access to the cabinet? Did I know where the key was?

I answered what I could. I watched the paramedic squeeze Mom’s shoulder like he was reminding a muscle it could do its job later. The mustache cop stood and left. When he came back, his eyes looked like he’d washed them in cold water and found nothing there worth saving. He nodded at Ramirez the smallest amount a head can nod.

“Ma’am,” Ramirez said gently. “We’d like to take you to the hospital just to—”

“No,” Mom said, voice flat. She wiped at her face with the side of her hand. “No. I’m fine.”

“Ma’am—”

“I said I’m fine,” she snapped, and then squeezed her eyes shut like a person apologizing internally to everyone she has ever loved. “I’m sorry.”

“We’ll leave a car on the block,” Ramirez said, standing. “If you think of anything, or if you need anything—”

Ryleigh laughed. It was a short, mean sound and it landed like coin against tile. “We need a time machine,” she said. “You got one of those in the trunk?”

Ramirez didn’t flinch. “I wish,” she said.

The house emptied of uniforms and competence. Silence inflated itself and tried to crowd us off our own furniture. The den door stayed shut like a lid. The evening crept up the windows and laid itself against them like a cat.

“Do you want tea?” I asked, to say a thing.

Mom stared at me like the question had been spoken in a language she used to know. She shook her head. Ryleigh went to the kitchen, opened and closed three cupboards, looked at the wall phone as if it would confess, and then came back out with nothing in her hands.

“Say something,” she told me, low and desperate and furious. “Say anything Max would say.”

My mouth opened like a drawer. Nothing in it was organized. “I’m sorry,” I said, because it had to go somewhere.

She stared at me for so long the air around her face seemed to waver. “When we went to Sleepy Falls,” she said slowly, “you were two. You carried a blue bucket everywhere and cried when you couldn’t find it and then it was on your head the whole time.” She tilted her head, studying mine like an x‑ray. “You told me that yesterday. From a picture.”

“I remember the trip,” I said. (I remembered a fox on a carved post, paw to its lips, telling someone to be quiet. I remembered a trail with too many choices pretending to be one.)

“Mom,” Ryleigh said, not looking away from me, “we buried Max last week.”

“Ryleigh.” Mom’s voice had crushed glass in it. “Not tonight.”

“When should I say it,” Ryleigh asked, and the way she said when was a plank thrown across a ravine. “When should I say that’s not him?”

Mom put her hands on her face and dragged them down, like she was trying to make a different one. She didn’t answer. Her shoulders shook like her body had decided to cry even if she had opted out.

I sat on the couch with my hands on my knees because hands on knees look normal. A clock somewhere decided to be a metronome for our breathing. Outside, a car passed, tires on asphalt like a whisper trying to be useful.

In the den, the hole in the wall from the day Benny squeezed the trigger waited for spackle that would never come. That felt important. A little math problem of cause and effect written in plaster dust.

Ryleigh slept on the couch across from me that night with one eye open. Mom slept on and off in the recliner, waking on the hour to look at me like she was watching a stove. The sky took its time with morning, as if it was trying to be kind and failing. When light finally found the living room, it didn’t look like any other light we’d had in it.

By noon, casseroles began to arrive, because grief makes people cook. They came with faces attached that said we didn’t know and we knew and we thought he was doing better and we always wondered and your boy and your husband and your brother and your. Some of them looked at me the way you look at a family portrait where one of the heads has been replaced by someone else’s head using scissors and glue. Some touched my shoulder and said you poor thing. The doorbell rung like it was working off a timetable.

Benny showed up around two with a plant from the grocery store and eyes that had been crying even before he got to our street. He stopped dead in the doorway when he saw me, then tried to arrange his face into something he could live with.

“Dude,” he said.

We stared. I watched the day I met him roll across his eyes like a movie played for an audience of one. He gripped the plant like it was a life preserver. He didn’t hug me. He didn’t leave. He stayed just long enough for me to see the part of him that wanted to say I’m sorry about a gun and the part of him that wanted to say I’m sorry about a coffin. Both parts lost. He set the plant on the coffee table and backed away like a person leaving a cage without letting the tiger know.

The first night was a lesson in how long a house can hold its breath. The second day was the part where the casseroles cooled and solidified into blocks you could build a small fort out of. The phone rang with people who didn’t want to say the word funeral and said service instead like euphemism could pay for anything.

At 3:17 p.m., a padded envelope arrived addressed to Dad from an insurance company with a return address that looked like it had been copied wrong. It slid through the mail slot and lay on the rug like a small animal sleeping. No one picked it up.

At 4:02, the doorbell rang and there was no one there. No kids with pamphlets, no package delivery, no neighbor with soup. The porch looked the way doors do when they’ve just swallowed something.

At 4:25, the light changed in the den without the lamp being on. It was a trick of clouds. It was nothing. It was something.

I stood up because standing up is what you do when you’ve noticed a thing and want to look like you haven’t. “Bathroom,” I said to no one and everyone.

In the hallway, the mirror above the console table caught me. For a second, my face didn’t look like my face. Not because it wasn’t—the parts were all right there where you’d expect—but because the way it sat on my skull seemed like a mask that had been put on by someone who wanted to do a careful job and didn’t understand the ritual of it.

I leaned in. My eyes looked back. Brown, tired. I thought very hard: What did you say to Jay in the basement? The answer didn’t come. Jay’s face did, the way it had gone blank right before the doorbell cam footage had gone out of frame. The way his mouth had pressed into a straight line like he was not going to say open out loud even though the shape of it fit in his mouth easily.

The hallway air felt colder than the living room air. The thermostat said it wasn’t. The hallway had opinions anyway.

Mom’s voice floated from the kitchen, not words, just the cadence of someone telling a story that has no middle and no end. Ryleigh’s laugh cut it, jagged, and then softened on the edges as if someone had filed it down.

I looked at the den door.

It looked back like a dare.

I turned away and went to the bathroom and stared at my hands again because hands are honest even when they aren’t. Then I flushed the toilet for the benefit of the house.

That night, after Mom fell asleep again in the recliner with the TV blue‑lighting her face, after Ryleigh’s breathing evened on the couch in a rhythm that meant awake and pretending, after the neighbor’s porch light clicked off, I lay on my back and watched the grain of the ceiling slide slowly toward the wall. My chest rose and fell. The house counted. The dark pressed its palm against the window and waited for me to match it. It’s rude to keep a guest waiting.

And sometimes, when you’ve been someone long enough, you start to wonder where you put the original box he came in.

If this is a confession, it’s a bad one. Confessions usually have more apologizing. This one has more weather.

I came home from summer camp in late September. My mother said my name like it had teeth. My father locked a door and then made a sound and then didn’t make any more sounds. My sister called the police and said a thing you don’t say in a house you want to live in anymore: That thing downstairs is not my brother.

And she might be right.

Or she might only be early.

—End of Part 1—

Part 2

The first week after Dad’s death moved like a shadow under the skin of the house.

It didn’t matter how much light we let in — the blinds drawn all the way up, the front door propped open during the day — it always felt dim inside. The air was wrong, like it belonged to a smaller space and was being stretched thin across too many rooms. Mom moved on autopilot, answering the phone, setting out food she never ate, thanking neighbors for pies she didn’t touch. Ryleigh watched me like she was waiting for me to trip over something only she could see.

The funeral came and went. Closed casket. No open discussion about why. Everyone cried in different shapes. Some cried like leaking faucets, others like storms that leave branches in the road. I didn’t cry at all, and every time I caught Ryleigh’s eyes across the church, her face tightened — not from grief, but from something sharper.

Afterward, I noticed the way she avoided being alone in a room with me. She’d linger in doorways if I was inside, ask Mom to go with her if she needed something from the basement, sleep with her bedroom door locked. She’d never done that before.

The day after the funeral, a small padded envelope arrived. Same as before: no return name, just a printed label from an insurance company. Mom opened it in the kitchen, then froze. Her fingers tightened on the paper until the veins stood out like ropes.

“What is it?” I asked.

She blinked hard, folded the paper, and shoved it into her apron pocket. “Nothing you need to worry about.”

Ryleigh glanced at me from across the counter. She didn’t believe her either.

Nights were the worst.

The house got quieter than any house should get. No creak of wood, no hum from the fridge, no wind through the siding. Like it was holding its breath. I started hearing small things — a faint scratching behind the den wall, the sound of water trickling somewhere it shouldn’t be, my name whispered so softly I couldn’t tell if it came from upstairs or inside my head.

One night I went to the bathroom at 2 a.m. and caught movement in the hallway mirror. Just a flicker — like my reflection’s face was still turning toward me after I’d already stopped moving. When I leaned closer, the skin on my cheeks looked too smooth, like a photo touched up by someone who didn’t understand human texture.

I didn’t tell anyone.

Three days later, Ryleigh finally confronted me.

It was late evening. Mom was in her bedroom on the phone, voice muffled behind the closed door. Ryleigh came down the stairs in her socks, stopped a few feet from me in the living room, and crossed her arms.

“Tell me the truth,” she said.

I looked up from the TV. “About what?”

Her eyes narrowed. “Where were you — really — the day you came home?”

“At camp,” I said automatically. “I got lost during a hike, found my way back.”

“Bullshit,” she said. “They found your body, Max. I saw it. I saw the photo they sent Mom before the burial.” Her voice wavered, but she pushed through it. “You had a gash across your face, dirt packed under your nails. You’d been dead for days.”

The air between us felt like a rope pulled tight.

“You think I’m lying,” I said.

“I think…” Her jaw clenched. “I think you’re not you. Not completely.”

She took a step closer. “So I’m going to ask you something only Max would know.”

My pulse thudded in my ears. “Go ahead.”

Her eyes searched mine. “What did you steal from my room when you were nine?”

I opened my mouth, but nothing came out. Not because I didn’t know — but because I knew too much. The answer rose immediately: the silver lighter with the skull on it she kept hidden in an old jewelry box. But another memory surfaced alongside it — something I’d never lived, not in this life. A small blue bucket in my hands. Ryleigh laughing as she lifted it off my head. The smell of wet pine and something sweet rotting in the grass.

“Max?” she pressed.

The answer that came out wasn’t the one I intended.

“The lighter,” I said. “Silver. Skull on it. You kept it in a wooden box under your bed.”

Her face drained of color. “I never told you where I hid it.”

I didn’t know what to say. The air between us felt like it was being pulled out of the room, replaced with something colder.

That night, I woke to a sound at my window. A slow, deliberate tap-tap-tap. I sat up in bed and listened. It came again. Three knocks, evenly spaced, from just the other side of the glass. My curtains stirred slightly, though the window was shut.

I crossed the room and pulled them back.

No one there.

Only the faint outline of the maple tree in the yard, its branches too far to reach my window.

I stood there longer than I should have, waiting for something to happen. And then I saw it — my own reflection in the glass, smiling when my mouth wasn’t.

The next morning, Mom said she was going into town to “handle some paperwork.” Ryleigh refused to let her go alone, so I was left in the house by myself.

At least, I thought I was.

An hour later, I heard footsteps upstairs. Slow. Careful. I crept to the bottom of the staircase and looked up.

Someone stood at the end of the hall. My height. My build. Wearing my clothes.

They turned their head toward me — and it was my face, down to the small scar on my chin from falling off my bike when I was eight. But the eyes… the eyes were wrong. Flat. Like glass marbles painted brown.

It smiled. Not wide, just enough to show me it could.

Then it stepped into my bedroom and shut the door.

When Mom and Ryleigh came home, I didn’t tell them. I told myself I imagined it. That I’d been tired. That grief makes people see things.

But later that night, I found the bedroom door locked from the inside.

The days blurred after that. I started noticing changes in the mirror. Sometimes my reflection was a half-second behind me. Sometimes its expression didn’t match mine. Once, brushing my teeth, I saw something black flicker across my eyes — not just in the iris, but filling the whites too — and when I blinked, it was gone.

Ryleigh watched me constantly now, eyes sharp, like she was waiting for proof to show Mom. I avoided being alone with her. I avoided being alone with anyone.

A week after the funeral, I woke up to find dirt under my fingernails. Dark, damp, smelling faintly of pine.

I hadn’t been outside.

And I knew — without knowing how I knew — that somewhere in the woods near Sleepy Falls, there was a shallow place in the earth shaped exactly like me.

That night, as I lay awake, I heard it again. The knock at the window. Three slow taps.

This time, I didn’t get up.

I just listened as the taps became a scrape. Then a voice, low and rasping, that sounded like mine.

“Let me in,” it said. “You don’t have to do this.”

I think Ryleigh is right.

I think I came back wrong.

And I think whatever’s still out there in the woods wants the rest of me back.

The only question is — what happens to the thing wearing my face when it does?

END!

News

We tried summoning a demon as a joke. But something answered.

Part 1 I didn’t believe in any of it. Not really. Demons, rituals, salt circles… all that stuff felt like…

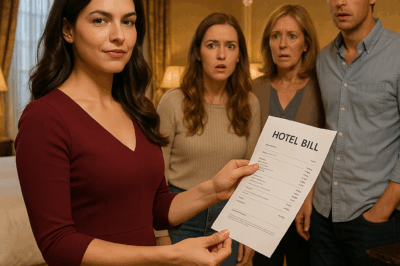

They Mocked My Tiny Apartment—So I Booked Them a Luxury Hotel… Then Left Them the Bill

Part 1 I always thought I was a patient person. Turns out seven years of being married into Thomas’s family…

Parents Took My College Fund for My Brother’s Startup, Then Refused to Pay Me Back

Part 1 I always knew the exact moment I decided to destroy my family. It wasn’t when they drained my…

They Lied About My Illness For 25 Years To Fund My Sister’s Life

Part 1 I haven’t been allowed to drive alone since I was sixteen. Not because I’m a bad driver—no one’s…

Forgotten at Dad’s Birthday—Until I Forwarded That Email

Part 1 I stared at my phone, fingers trembling as I scrolled through the Instagram photos. There they all were—Mom,…

Kristin Cabot’s Son Breaks Down on Live TV as Andy Byron Affair Scandal Escalates

The Andy Byron affair scandal has taken a heartbreaking turn after Kristin Cabot’s 17-year-old son broke down in tears during…

End of content

No more pages to load