I Said Goodbye to My Dying Husband and Walked Out of the Hospital—Then I Heard the Nurses Talking

Part One

I sat on a wooden bench outside Vanderbilt University Hospital and squeezed my hands together so hard my knuckles went white. Dogwoods were blooming along the walkway, and light broke itself into a thousand glittering fragments on the glass facade. None of it reached me. Somewhere behind those panels and corridors, my husband was losing a fight against an enemy we never saw coming.

Daniel had always looked like motion even when he stood still—broad-shouldered and calm in ways I never learned how to be. He’d work a twelve-hour day in his custom furniture shop, then come home and open a bottle, cook something loud and buttery, and ask about the smallest details of my shift like a man collecting seashells—this one mattered because I found it, that one because I handed it to him. He gave the kind of attention that made the ordinary feel held. It seemed inconceivable that anything could pry him loose from this world. And then six months ago, bruises bloomed inexplicably across his arms, and his breath shortened as if the air had thickened.

“Aplastic anemia,” the hematologist said, like the words were a set of doors he was opening for us and none of them led outside. “Severe. Your marrow is shut down.” He was a gentle man but the gentleness made it worse. He explained what I already knew in my bones: without a stem cell transplant, Daniel didn’t have time. Without a living relative, the odds of finding a match on the registry fell from slim to impossible.

Daniel grew up in foster care. He carried the facts of it lightly, the way you carry something sharp without pressing too hard. He didn’t know his parents, didn’t know siblings; he had memorized the names of houses instead and the false starts inside them. We swabbed his cheek and registered like we were dropping a letter into a storm and asking the ocean to deliver.

I tried to be brave, which in practice meant hiding in the bathroom at night with a towel over my mouth so the sounds I made wouldn’t puncture the hope in the other room. He tried to be impossible, which is to say he kept filling the room with jokes about hospital gowns and baldness like the air wasn’t thick and his bones weren’t tired. When he thought I was asleep, he prayed quietly. I kept my head on his pillow and learned the shape of his breath.

The afternoon the doctor pulled me aside with that new carefulness in his voice, spring was sweet and blind outside. “Emily,” he said, “we are running out of options.” He didn’t finish the sentence and didn’t need to. He was a good doctor and good doctors don’t pretend grace where there isn’t any.

I went down to the courtyard to practice breathing. Two hospital employees sat on a bench under a dogwood, laughing about something that had nothing to do with grief or platelets or death. I envied them. They were talking about weekend plans when one of them said, almost idly, “You know that guy in ICU—Carter? He looks just like this guy who lives out in Pine Hollow. I swear it’s like looking at the same person.”

The entire world pivoted on a hinge no one else heard. Pine Hollow—a small mountain town two hours east of Nashville where the roads turn to thread and the sky hangs lower and kinder. It was nothing and also it was everything. I stood there with the idea thrumming in my chest like a second heart: What if Daniel has family out there? Hope is a dangerous thing if you let it run without a leash; it drags you places you didn’t plan to go. But if the alternative is to sit on a bench while the air smells like flowers and your life narrows to a monitor’s green line, you put one foot on the path and follow.

I said goodbye to my dying husband ten minutes later. I kissed his forehead and smoothed the hair the chemo hadn’t yet taken and told him I’d be back before he missed me. “You look like you’re about to take on the world,” he whispered, mouth crooked in that way I loved. “I might be,” I said and left before my mouth betrayed the rest.

Pine Hollow had the same tired bridge I’d driven across once during nursing school. I stopped at the general store because that’s what you do in towns where news is currency and kindness is still legal tender. I showed the clerk a photo of Daniel—September sunlight on his face, sawdust in his beard—and asked if he’d seen anyone who looked like this. The man blinked, softened, and nodded. “You’re probably talking about Luke Henderson. Out County Road Six. He does odd jobs for half the town. There’s a little boy who calls him Uncle because he fixes everything.”

The house was tired in the way houses are when there isn’t enough money and too much work. The front steps groaned under my weight. He answered the door with motor oil on his hands and a question in his eyes. And then he saw the picture.

For a long moment he said nothing. Then he took a step back like someone had pushed him. “I’ll be damned,” he said, and his voice was already breaking. “Who are you?”

“Emily,” I said. “His wife.”

He looked at the photo and then at me and then at the photo again. “Come in,” he said softly.

The living room smelled like coffee and rain in a coat. He listened while I told him about Daniel—how he loved building walnut tables with joints that felt like forgiveness, how he kept his jokes quiet in hospital rooms, how the marrow that should have been making more of him had folded its arms and sat down. I said the words “no family” and watched something painful move across his face.

“Our mother wasn’t much of one,” he said finally. “There were a lot of us. Some disappeared into grandparents’ houses. Some into neighbors’ cars. One—” He swallowed. “She had one in a hospital when I was seven. A boy. She said we were not keeping him. She signed things. I remember because of the way the nurse folded the papers. Like it mattered how they were creased. I always wondered if he was okay. That’s the kind of word I used then. Okay.”

He rubbed a hand over his face, leaving a clean stripe through the motor oil. “What’s his name?”

“Daniel,” I said. “Daniel Carter.”

“I’m Luke,” he said. “Let’s go.”

He didn’t ask for time to think or a day to prepare or a lawyer to call. He grabbed his keys and we left Pine Hollow with the rain starting and then deciding it would go all in. He followed me to Nashville with the wipers smearing water into the shape of a future I didn’t dare describe to myself in case I jinxed it.

Daniel was awake when we walked into his room. The color drained from his face and then flooded back in the way sun moves across a wall. He looked at Luke and I watched recognition happen on a level deeper than sight. The part that knows its own.

“I think I’m your brother,” Luke said.

Daniel’s mouth opened like a prayer. He held out his hand and Luke took it without needing instructions. I stepped back into the hall and let the thin hospital door muffle the sound of two men meeting a version of themselves. A nurse wheeled a vitals cart by and smiled at me because she didn’t know what was happening and the world continues, the way it does, unaware and alive.

They tested him immediately. The hematologist came back with that expression good doctors get when the universe has surprised them for the better. “He’s a strong match,” she said. “One of the best.”

Luke laughed, one hand pressed to his chest as if holding in joy might keep it from spilling. “Tell me where to sign,” he said. “Tell me what to do.”

He joked with the nurses during prep because that’s who he turned out to be. “Never thought I’d be donating my bones to a man I just met,” he said, and then, more quietly, to Daniel, “I’m glad it’s you.” Daniel squeezed his hand and said, “I dreamed of a brother. I didn’t think I’d get one.”

The transplant took all day and only minutes. It was like that. A procedure that looked simple enough if you didn’t understand how many miracles it took to get the bag of new cells into the room. I held Daniel’s hand while the nurse checked the line and looped the world into a circuit. “I’m here,” I whispered into his hair and the IV pump hummed a lullaby built out of perseverance and plastic.

We watched and waited. That’s the work after—the not doing, the trusting that what you can’t see is happening. I counted signs like rosary beads: the flush in his cheeks, the steadier voice, the way his hand found mine without the effort it had cost him the week before. Luke slept in a broken recliner when he wasn’t running back to Pine Hollow to keep the animals alive and the truck from rusting in place.

When they finally let us take him home—our house now felt generous enough for three—Daniel stopped in the doorway the way men do who have learned that thresholds are a blessing.

“You built this,” I said quietly.

“We did,” he corrected, and his smile wasn’t the kind you give the camera; it was the kind you give the person who helped hold your ribs closed while the storm finished.

We moved into a life shaped by gratitude rather than the desperation that had been eating the edges. Daniel made his way out to the garage the second week and put his hands on wood, and the sound the plane made when it met the board was loud enough to drive away nightmares. He built me another rocking chair. He put it next to the first one—the one he’d made when his hands were still sure they would always be strong—and we rocked in both and watched fireflies make their tiny temporary promises.

Luke became a regular like he’d always been a recurring character and we’d just missed his early lines. He told stories about a mother who tried sometimes and failed often and a father whose initials he still carried in a pocketknife. He placed the knife in Daniel’s palm. “It’s the only thing of him I had,” he said. “Now we both do.”

The community of Pine Hollow mailed casseroles and notes and quilts. People signed letters with phrases that would have sounded quaint if they hadn’t felt like stitches. Family is everything. Hold each other close. I taped them to the fridge. When grief tried to creep back into a corner and crouch there like it owned the room, I pointed to those papers and said, “Not today.”

Outside, Nashville’s skyline looked the way it always does—like a city practicing for the day it will be bigger. Inside, I breathed without counting. Daniel’s hair came back in a soft crop that made him look seventeen for a week. Luke figured out how to make his coffee without apologizing for how strong it was. We learned to sit on the porch without feeling like we had to fill the silence with gratitude. You can be grateful without announcing it every minute. That’s called rest.

One evening while the sky burned itself down to embers and then flickered out, Daniel said, “I grew up thinking being an orphan meant I was alone. Turns out it meant I was practicing for when it mattered to hold on.” He took my hand and then Luke’s and looked at us the way men look at the road they almost didn’t make it back to.

“You never were,” I said.

“Maybe not,” he answered. “But it felt like it until you.”

I leaned my head on his shoulder. The world made its small noises. Gravel settled in the drive. A dog three houses down decided he would announce the moon. Somewhere behind us a neighbor’s radio played a gospel song in a minor key and I thought, This is the sound of my life turning back into itself.

Part Two

The nurses outside Daniel’s room that day didn’t know their small, bright conversation was going to shift a life. They didn’t know about the bench, or the dogwoods, or the way a woman makes a promise to a man sleeping under a machine—that she will fix it—and then goes looking for a mountain that might answer. They didn’t know they were opening a door I had been banging on with both fists for weeks.

I think about that whenever I walk past a group of people in scrubs laughing about lunch. There’s a world between their words that has nothing to do with me and then suddenly everything. It’s a good reminder to be careful with your ordinary because it might be someone else’s lifeline.

We built a new ordinary that fall. It didn’t feel like a replacement. It felt like an addition—space cut out of fear to make room for something alive. We added Luke to our family the way you add a plank to a bridge: carefully and then with your weight. He found a job with a local contractor who couldn’t believe his luck and also called him “boy” affectionately even though they were the same age. Daniel built a bench for the front yard and carved both of their initials where only I knew to look.

On Sunday nights, we ate at our table even if the meals were nothing fancy. Sometimes the three of us fell quiet and then all started to speak at once. It became a joke. “You first,” Daniel would say, and I’d nod to Luke and he’d nod to me and we’d end up talking over each other anyway. Laughing in houses where beeping used to be louder is a rebellion I highly recommend.

One golden evening, we walked the road toward Pine Hollow while the leaves made a show of departure. Luke swung his best friend’s little girl on his shoulders and she squealed as if the world had been waiting to lift her up. “I used to think I’d never have this,” Daniel said, squeezing my hand, “and I don’t just mean the health. I mean the belonging.”

“You do,” I said. “And it has your name on it.”

He turned that over in his mouth like a small miracle. “Sometimes you get exactly what you need after you’ve done the math on how you won’t,” he said finally. “And it still feels like luck.”

We were not saints. There were days I snapped because the pharmacy took too long and nights when the fear came back through a window we’d thought we’d nailed shut. There were doctor appointments that went fine and one that didn’t. There was a fever and a weekend in the hospital I didn’t tell anyone about because I didn’t want the world coming in at the edges. There was the morning the lab called and said the counts were good all in capital letters, and I put the phone down and cried so hard on the kitchen floor I couldn’t stand up for fifteen minutes. Luke sat with me and didn’t try to fix it. That’s the thing with brothers: they know when you’re allowed to cave and when you need to be told to get up.

Winter came with a quiet that felt like a kind of agreement: We’ll all rest now. Daniel’s hair came back enough to hold a thumbprint. Luke built a shed. I started jogging short distances that did not become marathons and that was fine. The hospital called less. The world called more. Sometimes a neighbor would drop a pie on the porch and we’d laugh because we didn’t know them that well. Outside kindness makes a good house better. I recommend accepting it even if you don’t know what to do with a buttermilk pie.

In January, we drove to Pine Hollow to watch the sky pretend to be a painting. Luke’s front room was crowded with people who had loved him long enough to be surprised and pleased by the new story. They all hugged Daniel too hard and he didn’t mind. He let them whisper “miracle” and didn’t correct them. He told me later that the word didn’t make him uncomfortable anymore because he didn’t think of the transplant as a lightning strike. “It was work and wonder,” he said, “and I can live with both.”

One night by Luke’s fire, the wind trying to get in at the edges and the wood saying no, Daniel pulled a small bundle from the pocket of his coat. He set it in my palm. Inside was a note—his handwriting steady again—and a ring he had taken off the day the doctor said marrow and put back on the day he could walk to me from the porch without holding the rail.

You are my always, the note said. The same words he’d framed by the kitchen door years ago. He didn’t kneel because the ground was frozen and his joints weren’t done forgiving him. He didn’t say anything because silence said it better. I slid the ring on and nodded and then laughed because sometimes joy needs a sound to move through.

We married in the church Luke’s grandmother had cleaned for forty years. The aisle creaked and the flowers smelled like someone’s backyard. The dress was borrowed from a woman whose daughter had decided Paris was more romantic than Tennessee; it fit because grace sometimes does. Daniel cried when he saw me the way he had cried under the oak tree and I loved him more for not pretending courage is the absence of tears.

When you carry death close for a while, you discover how to set a table for grief—leave a chair, pour a glass, nod when it shows up uninvited. But you also learn how to be impolite to it. To dance in front of it. To laugh so loudly it moves to the kitchen and leans against a counter and rolls its eyes and then sits down and claps because you’re good at this.

Months after the wedding, I went back to Vanderbilt on my day off to drop off brochures for a donor registry drive the Pine Hollow church had organized in Daniel’s honor. I stood in that courtyard again under the dogwoods. Two nurses were on their break, talking about spring. One of them looked up and said, “Hey, you’re the Carter wife, aren’t you?”

“I am,” I said.

She smiled and told me they still talked about the day two men who looked like each other found each other in a room no one liked to go into. She didn’t know she’d been a hinge in the door back then, and I didn’t tell her because sometimes leaving magic unnamed lets you keep it.

On the way out, I sat on the bench where I’d once practiced breathing. The hospital’s glass shone like a promise, or a dare, depending on the day. I thought about the first night I’d whispered in the bathroom into a towel and the day I’d driven to Pine Hollow with nothing but a picture and audacity and the way hope can feel like an insult until it’s the only thing keeping you upright. I thought about two men whose lives had failed to intersect and then did and I thanked whatever you thank when there are too many names and not enough answers.

I went home to a house that looked like itself again. Daniel was in the shop with the door open, music low, plane talking to walnut. Luke was in the yard, hands on his hips, surveyor of projects he would get to in his own time. I walked through the house touching the backs of chairs, the edge of the sink, the note by the door. The ordinary felt like a cathedral.

On the porch that evening, someone asked if I ever thought about the bench and the conversation I’d overheard, and I said yes, all the time. Not because I wanted to live in the past but because I wanted to remember how small things save you—how a sentence spoken by two women on break can pull a thread that unravels a noose.

“Do you ever think about what would have happened if you hadn’t heard them?” Daniel asked.

“I don’t,” I said. “Because I did.”

He nodded like we’d just agreed on what to have for dinner. We rocked in both chairs and watched the fireflies pretend to be stars and the stars pretend to be close and the world turn itself toward night with the only confidence it owns: that morning is not a myth.

That’s how our story ends—at least this chapter. Not with a curtain call in a sterile room, not with a list of numbers, not with a tragedy we always knew was possible. It ends with a family on a porch, an extra chair for whoever needs it next, and the knowledge that sometimes life hands you exactly what you asked for at the last possible minute. And sometimes, when you’re on a bench outside a hospital with dogwoods in bloom, it hands you a sentence that sounds like gossip and turns out to be grace.

END!

News

Airport Security Dog Wouldn’t Stop Barking at a Pregnant Woman — Then Everyone Learned the Heartwarming Truth. ch2

The winter morning at Brighton International Airport had been humming along in its usual way — rolling suitcases clicking over the tile,…

“My Mommy Won’t Wake Up…” — The Cry at the Airport That Sent a K9 Officer Racing Against Time. CH2

The airport was unusually quiet that Sunday morning. Officer Janet Miller adjusted her duty belt as she and her K9…

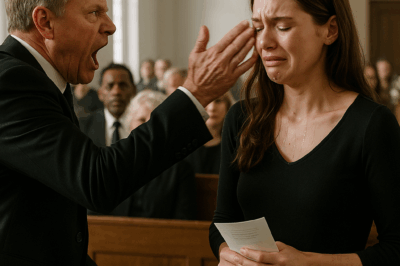

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”— So I Chose Revenge. CH2

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me and Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”—So I Chose Revenge Part…

My Brother Kicked Me Out After My Divorce, So I Prepared an Unexpected Surprise. ch2

Part 1: An Unexpected Betrayal I stood in my brother’s marble-floored foyer surrounded by moving boxes and the remnants of…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

Jeanine Pirro and Tyrus Declare War on CBS, NBC, and ABC—With $2 Billion Backing, Fox News Makes Its Move. ch2

In a shocking move, Jeanine Pirro has declared war on CBS, NBC, and ABC, and she’s not doing it alone….

End of content

No more pages to load