I Raised a Baby I Found in the Rubble — Then a Four-Star General Recognized His Necklace

When I was deployed overseas as a Marine Corps officer, I heard a baby crying in the ruins after an airstrike.

I carried him out and raised him as my own.

Years later, a visiting four-star general saw the pendant around his neck… and froze.

That day, the past, duty, and fate collided in a way I’ll never forget.

Part 1

My name is Captain Alyssa Hayes, United States Marine Corps, and the night that split my life in two began with a sound that had no business existing in that place.

A baby crying.

It threaded through the ruins in this high, frayed whimper that somehow cut straight through the hiss of cooling metal and the occasional crackle of distant fire. The firefight that had turned this village on the outskirts of Al-Rashir into a graveyard was already hours behind us. The ceasefire had held, the last shots gone quiet. Technically, the war was over for this piece of ground.

But nobody had told the baby that.

The air tasted like drywall dust and burned plastic. Smoke hung low over the collapsed houses, curling around the skeletal rebar like it wanted to hold on. My squad moved in a loose line ahead of me, boots crunching glass and bone-dry clay. We were there for mop-up: distribute supplies, stabilize survivors, log damage for some future reconstruction team. The kind of mission commanders call “low risk” on the morning briefing board.

I’d done three tours by then. I knew better than to trust the words “low risk.”

“Captain, east sector clear,” Corporal Diaz called over the radio. “No enemy activity. No civvies.”

“Copy,” I answered, but the hairs on my neck stayed up.

Because I could still hear it.

That thin cry again.

Not a cat. Not a wounded adult. Higher. Raw. Human infancy.

I lifted a hand and my squad halted automatically. “You hear that?” I asked.

Lance Corporal Nguyen cocked his head. “I got nothing, ma’am. Just the generators.”

I turned in a slow circle, listening past the mechanical noises and the radio static. There—a stuttered wail, muffled, like it was trapped under something heavy.

“Medic, on me,” I said. “Diaz, you’ve got the squad. Keep sweeping. I’ll be two mikes.”

“Roger that,” Diaz replied, no questions asked. That was one thing about Marines—if you sounded like you knew what you were doing, they’d let you walk straight into hell without slowing you down.

The cry pulled me toward what used to be a row of small houses near the old airstrip. Most of them were blackened shells now—roofs caved in, walls blown out. I stepped over chunks of concrete and twisted metal, the soles of my boots slipping in ash that had been somebody’s kitchen or bed or wedding photo.

“Hello?” I called in Arabic. “Is anyone alive? Anyone need help?”

Only the wind answered.

Then that cry again, sharper now. I followed it to a half-collapsed wall, a door blown off its hinges and buried under debris. A charred flight jacket peeked out from beneath a slab of concrete like a caught wing.

“Here,” I muttered, feeling my pulse climb.

“On your left, ma’am,” Doc Ruiz said, appearing at my elbow like he’d teleported. His face was streaked with soot, eyes already scanning for triage markers. “You got something?”

“Under there.” I shoved my rifle onto my back, wedged my shoulder against the broken door, and pushed. The muscles between my shoulder blades lit up, but the slab shifted an inch.

“Again,” Ruiz grunted, bracing beside me.

We heaved until my teeth hurt. The slab tipped enough that Ruiz could snake an arm under it and yank the door aside. Dust billowed up, hot and bitter.

Wrapped in that shredded flight jacket, nestled in a shallow hollow between cinderblocks, was a baby boy.

For a second, all my training fell away and there was just this one impossible fact: something that new and soft and alive was lying in the middle of a place built for death.

His face was gray with soot, streaked clean in tear tracks. Tiny fingers clutched the edge of the jacket and something silver on a chain. His lips were bluish, but moving. I saw his chest hitch.

“Doc,” I snapped, dropping to my knees. “Talk to me.”

Ruiz was already moving, fingers at his neck, eyes on his chest. “Pulse is thready. Breathing, but shallow.” He peeled back the jacket, checking for burns, broken bones, blood. “Looks like the rubble made a pocket. Jacket took the worst of it.”

“Any adults?” I scanned the rubble around us. No movement. Just the broken outlines of a building that had once had a purpose and now had none.

“Nothing,” Ruiz said quietly. “We’re it.”

The baby let out another weak cry, eyes fluttering open. They were this deep, dark brown, unfocused but stubbornly alive. His tiny fist clenched around the silver pendant again, pulling it into the light.

It was a small disc, dull from soot, engraved with coordinates and worn smooth around the edges. I couldn’t read all the numbers in that moment, but I saw enough to know it wasn’t just jewelry. It was a marker. A message.

“Command, this is Reaper Actual,” I said into my radio, forcing my voice level. “We have an infant survivor at grid—” I rattled off the coordinates for the ruined hanger. “Request immediate medevac.”

There was a hiss, then the cool voice from the forward operating base. “Negative, Reaper Actual. Medevac birds are prioritized for combat casualties only. Evac of non-combatants is to be coordinated through NGO channels.”

I stared at the ruins, the empty sky above them. “Say again, command? There are no NGOs. No local officials. This entire block is gone.”

Static, then: “Orders are clear, Captain. Secure the area. Transfer civilians to local authority or designated humanitarian partners. Medevac is unavailable for non-combatants at this time.”

I looked around at the flattened neighborhood, at the absence of sirens or uniforms or any sign of a functioning government. The only thing alive within shouting distance was cradled in the crook of my arm.

“Local authority,” I repeated, more to myself than to the radio. “Roger that.”

I cut the connection before they could hear what I was really thinking.

Regulations are easy when the people they’re about are theoretical. It’s different when they’re heavy and warm in your arms, breathing against your chest like a question you can’t afford to answer wrong.

I stuck the butt of my rifle in the dirt and slung it back over my shoulder. “We’re taking him to the schoolhouse,” I told Ruiz.

“You know that’s going to cause a paperwork storm,” he said, but he was already tucking his kit back together. “What are we calling him?”

I looked down at the baby. He blinked once, slowly, like he was unimpressed by the chain of command.

“Ben,” I heard myself say. “Short for Benjamin.”

“Any reason?” Ruiz asked, more out of habit than curiosity as we moved.

I shook my head. “Feels like a name that survives things.”

We set up the temporary triage center at what used to be the village school. The chalkboards were cracked, desks overturned, but it was the tallest building still standing. The medics moved among rows of cots, checking bandages, logging injuries, murmuring soft reassurances in two languages. Generators hummed in the courtyard. The smell of antiseptic tried and failed to cover the stink of smoke.

I made a nest for the baby in a spare cot, propping him up with folded blankets. His flight jacket was too burnt to keep, but I cut the pendant free and looped it around his neck again. I cleaned his face with water from my canteen, wiping away soot and grit until skin appeared—pink, new, fragile.

“You’re okay,” I told him, my voice scratchy from smoke. “You’re here. You’re okay.”

He stopped crying.

Just…stopped. He stared up at me with those dark eyes, serious and unblinking, as if he was trying to decide whether I was worth trusting.

I’d been in plenty of impossible situations. Ambushes, sandstorms, political quagmires, meetings with colonels who liked to hear themselves talk. None of them had put a knot in my throat like having that tiny, misplaced life look at me like I was the whole world.

That night, while we queued up bodies for the cold reefer truck and tried to find enough blankets for the ones still breathing, I sat on the edge of Ben’s cot and filled out my first report on him.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE INFANT. APPROX 9–12 MONTHS. FOUND AT GRID…

My pen hovered over the section for “Next of Kin.”

I left it blank.

When the generators finally cut for the night and the schoolhouse settled into the uneasy quiet of people too tired to move, I stayed awake. Ben slept with one fist curled around that pendant, the other resting on my dog tags where they lay against my chest. Every time I shifted, he tightened his grip like he thought I might disappear.

Regulations don’t cradle a baby at three in the morning. They don’t wake up sweating at the sound of a far-off collapse. They don’t stand in the rubble and decide who counts.

People do.

The chaplain came through the next day with a worn Bible and a tired smile.

“Heard you picked up an extra responsibility, Captain,” he said, nodding toward Ben, who was chewing furiously on the edge of a blanket.

“Picked up,” I repeated. “Like a piece of gear I forgot to return.”

He chuckled softly and sat on the cot across from me. “You know the Corps frowns on personal entanglements, especially downrange.”

“I read the manual,” I said.

He shrugged. “Good thing the Bible isn’t a manual.”

I raised an eyebrow. “You brought your recruiting pitch?”

He flipped open to a page marked with a ragged strip of MRE carton. “Just something you might want to consider.”

He read aloud, voice low. “‘Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress…’”

I finished the verse from memory, surprising us both. “And to keep oneself from being polluted by the world.”

“James,” he said. “You grew up in church?”

“Grew up with a mother who believed in it,” I said. “Big difference.”

“Maybe,” he said. “Maybe not.”

He closed the Bible. “You won’t find a chapter in any Marine Corps order on what to do about a kid like this. Sometimes orders come from higher up than command.”

I rubbed at my eyes with the heel of my hand. “You saying God wants me to take him home?”

“I’m saying you already decided something the moment you lifted that concrete,” the chaplain said gently. “The paperwork is just catching up.”

By the time my unit rotated back to the States, Ben was crawling, babbling, and laughing at the sound of rotor blades like they were his favorite song. The village had an NGO tent city, a few new wells, and a long list of names we’d never match to faces.

On my last night, my squad threw him a kind of makeshift farewell party. Diaz fashioned a rattle out of an empty shell casing and beads from some prayer bracelet. Nguyen stuck a smiley-face sticker on his forehead and said, “That’s your good luck charm, little man. Don’t lose it.”

In the mess tent, Ruiz looked at the stack of adoption and guardianship forms I’d been compiling and shook his head. “You sure about this, ma’am? Bringing him back is going to be hell on your career.”

I looked over at Ben, asleep in an ammo crate converted into a crib, one hand curled around his pendant.

“So is leaving him,” I said.

On my final mission log, under “Results,” I wrote: One survivor recovered. Condition: stable. Action: ongoing care.

The C-130 that carried us out of Al-Rashir lifted off in a roar of hot wind and dust. I held Ben against my chest as the desert shrank below us into a wash of tan and shadow. His tiny fingers played absently with the edge of my dog tags, then with his own pendant. Metal tapped metal, a small, steady sound.

Out the small round window, the world parted into sky and earth. Between them, in that noisy, vibrating space, I knew three things:

War had already taken more than it ever had the right to.

This boy’s life was now inexplicably tied to mine.

And that little silver disc hanging around his neck was not an accident.

I didn’t know what the coordinates meant yet.

But I knew they meant something.

Part 2

Cherry Point, North Carolina, greeted us with cold air and the thin winter light of a sky that hadn’t seen a mortar in its life.

The plane’s ramp dropped with a hydraulic sigh, letting in the smell of jet fuel, wet tarmac, and the Atlantic. Marines shuffled out with their seabags and tired jokes, faces turned toward home.

I walked down that ramp with a baby under my coat.

Ben’s cheeks were pink from the temperature shock, dark eyes wide as saucers. He didn’t cry. He just looked.

I envied him that newness. The base, the runway, the hangars—it all felt too familiar to me, like clothes that had been washed too many times.

“Captain Hayes,” a lieutenant from legal affairs called as soon as my boots hit the ground. “You need to report to admin before you depart the base.”

“Can I drop my gear first?” I asked.

He glanced at the bundle in my arms. His eyebrows twitched. “Ma’am, that would be…part of admin.”

The nightmare started before I even reached my on-base apartment.

In a beige conference room that smelled faintly of coffee and printer toner, a major from JAG leafed through the stack of forms I’d been compiling. Each sheet documented some angle of Ben’s existence: witness statements from my squad, the chaplain’s letter, the NGO reports confirming no surviving family, the Red Cross’s failed attempts at tracing relatives, my request for emergency guardianship.

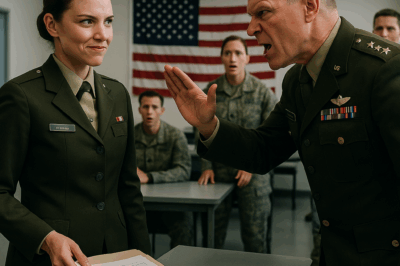

The major tapped the edge of the file against the table. “You understand this is highly irregular, Captain.”

“Yes, sir,” I said. “So is finding a baby under a collapsed hangar.”

“We can’t even prove where he’s from,” he continued. “No birth records. No surviving parents. No local authority to sign off. For all we know, he could be—”

“Alive,” I cut in. “He’s alive. And the only reason he’s here instead of buried in that rubble is because I picked him up.”

He frowned. “We’re not questioning your intentions. But we have systems for orphaned children overseas. You could transfer him to child protective services. Let them—”

“Handle it,” I finished for him. “With all due respect, sir, I’ve seen what ‘systems’ do to kids like him in places where the paperwork is the only thing that moves.” I leaned forward. “If I hand him over, what happens next?”

“Foster placement, ideally,” he said, but his tone lacked conviction. “Possibly a group home.”

“And what,” I asked quietly, “are the odds that somebody looks at a brown-skinned war baby with no paperwork and decides he’s worth the hassle?”

The major exhaled through his nose. “You’re not the first service member to want to bring back a child,” he said. “Most of those stories don’t end well, Captain. For anyone.”

I thought of the laundry basket I’d already converted into a makeshift crib in my apartment. Of the way Ben’s fingers grabbed my sleeve when I tried to hand him to anyone else. Of the nights in the schoolhouse when his breath had been the only sound that cut through the ghost-noise in my head.

“With respect, sir,” I said, “most of those stories start with people who weren’t ready for both wars.”

He blinked. “Both?”

“The one overseas,” I said. “And the one waiting for them when they get home.”

He studied me for a long moment, then slid a different form across the table. “You want to do this the hard way, there is a mechanism still on the books. Wartime humanitarian guardianship. It’s a relic from Vietnam, hardly ever used. It will put you under a microscope. Your career progression will slow. Your personal life will be…complicated.”

I picked up the pen. “My personal life is already complicated, sir. Why not make it worth something?”

The first night back in my apartment, the silence pressed against my ears. No generators. No sporadic gunfire. No restless shifting of a dozen exhausted Marines.

Just the hum of the refrigerator and the distant roar of jets practicing touch-and-gos.

I set Ben down gently in the laundry basket next to my bed, the one I’d lined with folded towels and the extra blanket I’d never used. He wriggled, then settled, one hand immediately finding the pendant against his chest.

I sat on the edge of my bed, staring at the medals hung neatly on the wall. Bronze Star. Humanitarian Service Medal. Proof that I had followed orders and impressed the right people.

They looked small from that angle.

I’d been trained to run toward gunfire, to patch bleeding wounds under fire, to call in air support and close air support and whatever support the situation demanded. I had not been trained to mix formula at 2 a.m. or decipher the different pitches of a baby’s cry.

But war had given me this mission, and for the first time in a long time, the order hadn’t come from the chain of command. It had come from somewhere older and quieter inside me.

Protect him.

I took down the medals, one by one, and set them gently in a drawer.

The next morning, my doorbell rang at oh-eight-hundred sharp.

I knew it was him before I even looked through the peephole. There are some footsteps you don’t forget.

I opened the door to find retired Colonel Richard Hayes standing ramrod straight on my stoop, hands behind his back, jaw clenched.

“Is it true?” he asked. No hello. No hug. Just three words sharpened like a bayonet.

I stepped aside. “Come in, Dad.”

He scanned the apartment with quick, tactical eyes as he walked past—the neatly stacked moving boxes, the marine posters, the laundry basket crib. Ben gurgled from inside it, kicking his legs.

My father stopped.

The sight of the baby hit him harder than any briefing I could have given. He stared for a long moment, shoulders tight, face carved in lines I’d never noticed before.

“You brought back a child from a war zone,” he said finally.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“You think that’s compassion?” His voice went flinty. “It’s confusion, Alyssa. You’re a Marine, not a missionary. We don’t get to play God with people’s lives.”

Something in me snapped, quiet and decisive.

“Was it playing God when I called for medevac on a wounded lance corporal, sir?” I asked. “Or when I grabbed Ruiz by the vest and pulled him away from that RPG?” I pointed at Ben. “He was on my battlefield. That made him my responsibility.”

“You did your part,” my father shot back. “You pulled him out. You kept him breathing. Now let the system do the rest.”

“Would you have said that,” I asked, my voice softer than I felt, “if it had been me under that rubble?”

He froze. Just for a second. A crack in the armor.

Then he turned on his heel and walked out without another word.

Ben fussed, sensing the tension. I scooped him up, breathing in that warm, milky baby smell that somehow cut through jet fuel and disappointment.

“We’re okay,” I murmured into his hair. “We’re okay.”

The months that followed taught me more about endurance than any deployment ever had.

Daytime, I was Captain Hayes, Logistics Instructor, shouting over the clatter of training fields, teaching young Marines how to move supplies through impossible terrain, how to keep convoys fueled and fed and functional.

Nighttime, I was Mom, on-call for every whimper, blowout, and nightmare. I memorized the aisles of the commissary’s baby section, learned how to strap a car seat into the back of a government-issue sedan, and mastered the art of napping in fifteen-minute increments.

The gossip hit faster than the sleep deprivation.

“She brought him back from where?”

“Is that even legal?”

“I heard she had to sign away promotion consideration for the next five years.”

I let it roll off me. Marines will talk about anything that scares them until it’s small enough to joke about. If my unconventional motherhood gave them material, so be it.

What mattered were the moments nobody else saw.

Ben’s first laugh, when I accidentally dropped a spoon and he thought it was hilarious.

His first word—“mama”—clear as reveille one morning when I walked in with his bottle.

The way he’d quiet instantly when I hummed the marine hymn under my breath, as if some part of him recognized the rhythm of boots and brass.

The emergency guardianship process crawled through the Department of Defense, the State Department, and whatever other alphabet agencies felt entitled to weigh in. Every week, another interview. Another home visit. Another stack of forms designed by someone who had never changed a diaper after twelve hours on the rifle range.

One JAG lawyer raised an eyebrow at my file. “You understand, Captain, that if you deploy again, child services may want to revisit placement.”

“I understand,” I said carefully, “that the Corps can send me where it needs me. And that if they do, my son will be waiting for me when I get home.”

“‘Son’ is a strong word for a non-biological dependent,” he said.

“So is ‘brother’ for the Marines I’ve bled with,” I replied. “Doesn’t make it less true.”

The judge who finally signed off on the adoption wore her robe like armor. She was in her sixties, eyes kind but piercing. The courtroom was half-empty the day of the hearing. Just me, Ben in an ill-fitting baby suit, and a clerk tapping away at a keyboard.

“Captain Hayes,” the judge said, scanning the thick file in front of her, “this is not a standard adoption. It crosses international lines, military regulations, and a dozen bureaucratic tangles I’d rather never see again.”

“Yes, Your Honor,” I said, pulse in my ears.

She looked up. “And yet, every report I have—from your commanding officer to the chaplain to the orphan welfare liaison—says the same thing. That wherever this child came from, he is home now.” She smiled, just a little. “This is one of the rare times in my job where the law gets to do something that feels right.”

She reached for her pen. “By the authority vested in me by the state of North Carolina, I grant this adoption. The minor child shall henceforth be known as Benjamin Cole Hayes.”

Cole.

The middle name hit me in the chest, even though I was the one who’d written it on the forms. It had floated up one night as I stared at the pendant, tracing the letters half-burned into that old jacket scrap. C-O-L-E.

I didn’t know then what all it would come to mean. I just knew it seemed to belong to him.

“That’s it?” I asked, stunned. “Just like that?”

The judge laughed softly. “Trust me, Captain, there is nothing ‘just’ about what you’ve done. Now go home. You have a son to raise.”

Outside the courthouse, the air smelled like cut grass and exhaust. Ben squirmed in my arms, chewing on his bow tie.

My father called that night.

He didn’t clear his throat first, the way he usually did when he was gearing up for a speech.

He just said, “Your mother would have been proud.”

I stared at the phone. “Of what? Breaking protocol? Making your life complicated?”

“Of following your orders,” he said. “Not the Corps’s. Yours.”

“Dad, the Corps—”

“The Corps doesn’t know everything,” he cut in, which for him was akin to blasphemy. “Just…don’t let this soften you, Alyssa. The world you work in…it eats sentiment for breakfast.”

“It’s not sentiment,” I said, the words coming from somewhere deep and newly solid. “It’s service. Just a different kind.”

He didn’t respond for a long time.

Then, quietly: “Wear your cover straight. Teach him to say ‘sir’ and ‘ma’am.’ The rest we’ll figure out.”

Years went by.

I transferred to a training unit stateside for good, trading sand and incoming rounds for whiteboards and PowerPoint. My days filled with young Marines learning how to move mountains of supplies into places the world had forgotten.

My evenings filled with homework, bedtime stories, and the constant low-level chaos of raising a boy who seemed determined to touch every surface and ask every question.

We settled into a rhythm. Ben grew fast and smart and stubborn. He organized his toy soldiers into fire teams and demanded after-action reports on his own Lego disasters.

Every few months, he’d hold up his pendant and ask, “Where’s this from again, Mom?”

“From the sky,” I’d say, which was close enough to the truth and easier than explaining international law to a five-year-old. “It fell to you like a gift.”

Sometimes, late at night when the house was quiet and the ocean’s hiss drifted in through the cracked window, I’d take the pendant off his neck and hold it under the lamp. The coordinates were worn, but legible. I’d trace them with my thumb and tell myself that one day I’d punch them into a map and see what they pointed to.

But there was always something more urgent. A field exercise. An ankle sprain. A science fair project about volcanos that needed last-minute papier-mâché. Life has a way of making the past wait its turn.

Until the letter arrived.

It showed up on a Tuesday in spring, tucked between a utility bill and a glossy pizza coupon.

Marine Corps Heritage Banquet, the embossed script on the envelope read. You are cordially invited…

I slit it open with my thumb, standing at the counter amidst cereal bowls and Ben’s abandoned crayons. The invitation was for officers who had distinguished themselves in humanitarian operations. My name was on the list.

I huffed a laugh. “Distinguished” is not how I would’ve described the months of forms, midnight feedings, and arguing with bureaucracy.

But it felt like a checkpoint all the same. A moment to stop and see how far we’d come from that collapsed hangar.

Ben shuffled into the kitchen in socked feet, eyes still puffy from sleep.

“What’s that?” he asked, leaning on my arm.

“An invitation,” I said. “To a fancy dinner on base.”

“Do I get dessert?” he asked thoughtfully.

“Almost definitely.”

“Then yes,” he said. “We should go.”

I looked at him—his messy hair, his serious eyes, the pendant glinting at his collarbone—and felt something like a road turning under my feet.

Maybe it was time he saw the world I came from. Not the ruined villages and burning hangars, but the other side. The uniforms and flags. The part that was about building instead of breaking.

I had no idea that the banquet would crack open everything I thought I knew—and that the coordinates on his necklace were about to point straight back at us.

Part 3

The week leading up to the banquet felt like the base was getting ready for inspection from someone much higher than a general.

Mess dresses came back from the cleaners in crisp plastic. Young Marines practiced table etiquette in the chow hall, trying to remember which fork to use while their buddies heckled them.

In the training room, I showed my recruits how to write an appropriate toast. “Keep it under two minutes,” I said. “Stand up straight. Don’t try to be funny unless you’re actually funny. Honor the absent.”

At home, I ran my life like a joint operation. Lesson plans pinned to the fridge next to Ben’s spelling tests. Gear list on the whiteboard. Banquet checklist in my head.

I ironed my dress blues while cartoons flickered in the living room. A breeze from the Atlantic slipped in under the kitchen curtain, moving the edge of the invitation where it sat on the counter.

Cherry Point has a way of sanding some of your sharper edges. On a good day, the sound of waves and rotors layers into something almost comforting.

But there are edges you keep deliberately. The ones that remind you who you are when the noise dies down.

I kept those tight while I got Ben ready to see my world.

We practiced handshakes in the hallway, his small fingers wrapped around my own.

“Look people in the eye,” I told him. “Say, ‘Nice to meet you,’ even if you’re not sure yet if it is.”

He bounced on his toes. “What if I forget their name?”

“Then ask again,” I said. “Names matter.”

Two days before the banquet, I took him to the barbershop on Main Street. The place smelled like talc and aftershave, the walls covered in framed photos of ships and squadrons.

Chief Hartman, Navy retired, lifted Ben into the big chair, wrapping a rocket-printed cape around him. “So,” he said to me, clippers in hand, “you bringing this one to the big shindig?”

“I am,” I said.

“Good,” Hartman grunted. “Heritage ain’t just for the old folks.” He eyed the pendant at Ben’s neck. “Interesting necklace.”

“Found him with it,” I said.

Hartman nodded once, no further questions. Sailors are good at recognizing when something isn’t theirs to pry open.

He turned to Ben. “You take good care of your mama, hear? She took damn good care of you.”

“Yes, sir,” Ben said solemnly, as if he’d just accepted an official assignment.

My father and I were circling each other like two ships trying to find the same harbor from different charts.

He’d started dropping by on Sundays with bags of tools, fixing things that didn’t strictly need fixing. Tightening cabinet hinges. Oilings doors that didn’t squeak. Standing in the garage, polishing my old NCO sword while pretending not to watch Ben draw chalk lines on the driveway.

When I told him about the banquet, he just nodded, face unreadable.

“Wear the blues,” he said. “Let the boy see who his mother is.”

He said “mother” like it was a rank.

On the afternoon of the banquet, the sky went that particular Carolina blue that always makes me think of dress uniforms. Ben and I dressed slowly, like we were suiting up for something more than dinner.

I pulled on my dress blues, smoothing the skirt, pinning my ribbons in the precise line that marked time and places and things I’d rather not remember.

Ben wore a navy blazer and a clip-on tie that kept listing to the side. I straightened it, then lifted his pendant and tucked it under his shirt.

“Keep it close,” I said.

“I always do,” he answered easily.

We stopped by my father’s house on the way to base. He stepped out onto the porch in a blazer that didn’t quite fit his smaller frame anymore, the fabric stretching across shoulders that had carried too much.

He looked Ben up and down, cleared his throat. “You look squared away, son.”

“Thank you, sir,” Ben said, standing a little taller.

My father handed me a small velvet box without ceremony. Inside were my mother’s pearl studs.

“She’d want you to wear them,” he said, voice low. After a beat, he added, “I’m proud of you, Captain.”

For my father, that was the equivalent of a full brass band and fireworks.

The officer’s club looked the same and different when we walked in. Fresh paint on the walls, new portraits alongside the old. But the smell of polished wood, aftershave, and decades of stories pressed into the carpet was the same.

A brass quartet played near the stage, the notes threading through the clink of silverware and low conversation. A banner hung above the podium: HONORING SERVICE BEYOND THE BATTLEFIELD.

Heads turned as we walked in. Not a lot of single moms bring their five-year-olds to heritage banquets.

Ben’s hand tightened around mine. “Mom,” he whispered, “are all these people soldiers?”

“Marines,” I corrected gently. “And tonight we’re mostly celebrating peace.”

We found our table—six, near the front. My father was already seated, back straight, shoes polished to a shine you could salute in.

He gave me a short nod that translated to: You’re on time. You look right. I’m not going to say more, but it’s there.

“Remember how to salute?” he asked Ben.

“Yes, sir,” Ben said.

“Good man,” my father murmured.

The program started with a prayer, then a slideshow of images projected onto a screen at the front. Flooded towns. Helicopters hovering over rooftops. Marines passing water bottles down human chains. A medic cradling a dusty toddler on a stretch of highway.

For a moment, I thought my heart stopped.

There, in one quick flash between two other photos, was me. Young, exhausted, desert cammies stained with God-knows-what, holding baby Ben in my arms in that ruined schoolhouse. His face was turned toward me; mine was looking at the camera like I’d been caught in the act of feeling something.

A few people at nearby tables glanced my way. One whispered, “That’s her.”

I kept my face neutral. Marines are good at sitting perfectly still while the whole world shifts an inch.

The Master of Ceremonies eventually stepped up to the mic.

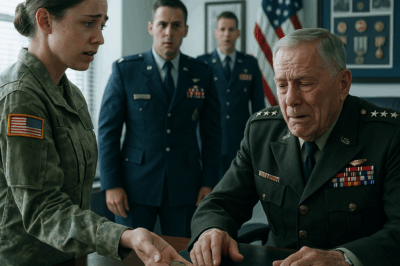

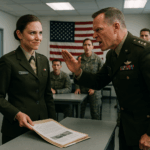

“Tonight,” he said, voice amplified and practiced, “we’re privileged to have with us leaders and heroes whose influence stretches from the front lines to the home front. Please welcome our guest of honor, General Robert Cole, four-star Marine, humanitarian advisor, and a man whose commitment to service has defined an era.”

The room stood as one, the scrape of chairs swallowed by applause.

The name hit me like a small, precise detonation.

Cole.

It was a common enough name in the Corps—which is why my brain tried to file it as coincidence and move on. But my hand went instinctively to the pendant under Ben’s shirt.

General Cole walked to the podium with the unhurried gait of someone who’d spent his life under scrutiny. Tall, gray-haired, uniform immaculate, the fruit salad on his chest balanced and heavy.

His face was not handsome in the conventional way. It was carved by sun, strain, and years of making decisions other people would live or die by. But his eyes…his eyes looked tired in a way I knew too well.

He didn’t thunder into the microphone. He spoke quietly, as if he understood that people lean in when you don’t force your voice on them.

“I’ve stood on more flight lines and more parade decks than I care to count,” he said. “I’ve seen courage in places most folks don’t have on their maps. The things we celebrate in rooms like this tend to be the big moments—the firefights, the rescues, the operations with names.”

He paused, scanning the room.

“But some of the bravest acts I’ve ever known don’t come with citations. They start in the quiet. In the moment when someone hears a cry nobody else hears and decides not to walk away.”

His gaze brushed past our table—just a flicker, the way a spotlight skims a crowd. For a second, I thought it paused.

Then it moved on. And I told myself I was being ridiculous.

My father leaned over. “Good man,” he said softly. “Lost his wife on a classified mission years back. Marine pilot. Never remarried.”

“How did she die?” I asked before I could stop myself.

“Officially?” he said. “Missing in action over the Eastern Ridge. Osprey went down on a humanitarian run. They never found the wreckage. Just some debris.”

The pendant at my son’s chest seemed to grow heavier against my forearm.

No, I told myself. It’s a big Corps. A big world. You’re connecting dots because that’s what your brain does when you’re nervous.

After the speeches, officers flowed around the room in small knots, shaking hands, trading deployment stories like weather reports. Servers wove between them with trays of stuffed mushrooms and tiny, impeccable desserts.

I stood near the dessert table with Ben, trying to convince him that one brownie was enough.

A young lieutenant in dress blues approached, looking like he’d borrowed his jawline from a recruitment poster.

“Ma’am,” he said, nodding at my ribbons, “if you don’t mind me asking…your son’s necklace. Is that an old aviation pendant?”

I looked down at the silver disc peeking out from under Ben’s tie.

“Yes,” I said slowly. “Why?”

The lieutenant shifted, suddenly uncomfortable. “I’ve seen one like it before. General Cole…he keeps its twin on his desk. Says it belonged to his wife.”

Before I could answer, a shadow fell over the dessert table.

General Cole himself stood there, flanked by a slightly panicked-looking aide. Up close, he looked exactly as he had from the podium—composed, contained, careful. But his eyes had a flicker in them, like a pilot trying to read an instrument suddenly giving off strange numbers.

He smiled at Ben, the way high-ranking officers do around kids. A little awkward. A little too wide.

“What’s your name, young man?” he asked.

Ben straightened instinctively. “Benjamin Hayes, sir.”

“Hayes,” Cole repeated quietly. “Strong name.” He glanced at me. “You take after your mother?”

“Yes, sir,” Ben said proudly. “She’s a Marine.”

Cole’s lips quirked. Then his gaze caught on something and froze.

The pendant had slipped fully into view. It lay against Ben’s shirt, glinting in the chandelier light.

For a heartbeat, the entire room dropped away. The hum of conversation, the clink of glasses, the band’s low music—all of it went distant.

The general’s face had gone ashen. The hand holding his glass began to tremble, just a little.

“Where…where did you get that?” he asked, voice suddenly hoarse.

Ben looked at me, alarmed.

I answered. “He’s had it since I found him overseas, sir. After an airstrike.”

The color drained further from Cole’s cheeks. “Found him,” he echoed. “Where?”

“In a village outside Al-Rashir,” I said slowly. “Five years ago.”

He set his glass down with exaggerated care, as if the slightest miscalculation might shatter it—or him.

“That area,” he murmured, almost to himself. “That’s…that’s where…”

His aide stepped closer. “Sir? Do you need—”

Cole took a step back from us, then another. “Excuse me,” he said stiffly, and turned away, moving through the crowd like a man walking through fog.

The aide scurried after him.

My father reappeared at my side, eyes narrowed. “What happened?”

“I don’t know,” I said truthfully. “I think…he recognized the pendant.”

My father’s gaze dropped to the necklace. He’d seen it a thousand times. Tonight, he looked as if he was really seeing it for the first time.

“Cole,” he said quietly. “And Cole.”

I swallowed hard.

Too many dots. Too many years. Too much coincidence.

Or not enough.

We left early. Ben was tired and sticky with dessert, and my nerves had frayed down to live wire.

On the drive home, he stared out the window at the blur of base lights.

“Was that man sad, Mom?” he asked.

“Which man?” I said, though I already knew.

“The one with all the ribbons,” he said. “The one who looked at my necklace like it hurt.”

I stared at the road ahead, the white lines ticking by like heartbeats.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “I think he was.”

That night, after I tucked Ben into bed—pendant back under his shirt, fingers wrapped around it even in sleep—I went to the garage and pulled out the fireproof box I hadn’t opened in years.

Inside were the relics of one night in Al-Rashir that had refused to stay in the past.

The original mission report.

A scalloped scrap of burnt fabric with the hint of embroidered wings.

And a sealed envelope I’d never had the courage to open. The label, in blocky official handwriting, read: PERSONAL EFFECTS.

My hands shook as I tore it open.

A photograph slid out. Its edges were singed; one corner had been eaten by fire.

It showed a woman in Marine flight blues standing on a tarmac, sun sharp on her face. Her smile was wide, confident, the kind you only give to the camera if you believe absolutely in the ground under your feet.

Around her neck hung a silver pendant.

The same pendant as Ben’s.

On the back, faded but still legible, was an inscription.

To R. COLE

Forever my wingman.

Under that, barely visible, a set of coordinates.

The same string of numbers etched into the pendant that now slept against my son’s chest.

Major Sarah Cole, USMC. Missing in action. Wife of General Robert Cole.

I sat down hard on the workbench stool, breath knocked loose.

I had thought, all these years, that I’d brought home a stranger’s child out of duty and instinct.

Turns out, I’d brought home the last living piece of someone else’s story.

The question wasn’t whether I could keep pretending I didn’t know.

It was whether the truth would save us—or blow us apart.

Part 4

I didn’t go to sleep that night.

I sat at the kitchen table with the photograph in front of me, the pendant warm in my palm, and the weight of two families pressing against my ribs.

My first instinct was to shove it all back into the box. To lock it, shove it onto the shelf, and never open it again. I’d built a life for Ben. A good one. Safe. Steady. Full of people who loved him.

Dropping a missing Marine and a grieving four-star general into the middle of that felt like pulling the pin on a grenade and hoping I could hold my thumb over it indefinitely.

My second instinct, the one that sat deeper and more stubborn in my bones, refused to let it go.

The Corps runs on honesty and silence in equal measure. You learn very quickly which one keeps your people alive in which situations.

But this wasn’t about operational security. This was about a boy who wore a stranger’s coordinates around his neck.

The next morning, I drove to my father’s house with the photograph face-down on the passenger seat.

He was in the backyard, kneeling beside the rosebushes he tended with the same precision he’d once reserved for weapons inspections. His hands were stained with dirt instead of oil.

“Morning,” he grunted without looking up.

“Dad,” I said, “I need you to see something.”

He wiped his hands on his jeans and stepped onto the patio, squinting in the light. I laid the photograph on the table between us.

He didn’t touch it. Not at first. Just stared.

After a moment, he picked it up, careful not to bend the burnt edges.

“That’s Major Cole,” he said quietly. “Met her once. Hell of a pilot.”

He flipped it over, saw the inscription. When he reached the coordinates, his jaw tightened.

“You knew her?” I asked.

“Just enough to want her covering my Marines’ six,” he said. He tapped the inscription with a thick finger. “This was on the jacket you found, wasn’t it?”

I nodded.

“And that baby you pulled out from under the hangar was wrapped in it.”

“Yes.”

We both knew the rest. We didn’t say it out loud. Some truths feel too big to fit in a human mouth.

“So what now?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, and that was a rare admission from either of us. “Part of me thinks I should put this back in the box and let everyone keep living with the ghosts they already know.”

“And the other part?” he asked.

“The other part thinks a man has the right to know his wife didn’t die for nothing. That her last moments gave someone a chance.”

My father stared out across his small, neat yard. The marine in him, the one who believed in chain of command and clean endings, warred visibly with the man who had buried a wife and watched a daughter come home with new scars.

“You stir this up,” he said finally. “Best-case scenario, it’s a mountain of paperwork and some very uncomfortable meetings. Worst case…”

He didn’t finish. He didn’t have to. Worst case meant headlines. Investigations. Questions about custodial rights and chain of custody and whether bringing Ben home had been a violation of something someone could put into a statute.

“I don’t care about the paperwork,” I said. “Or the politics. I care about Ben. And about not lying to him by omission for the rest of his life.”

My father sighed, the sound long and low. “Your mother used to say the truth is like a tide. You can build sandcastles against it, but it’s coming either way.”

“She was a poet now?” I asked, trying to lighten something that didn’t want to be lightened.

“She had her moments,” he said.

I went home and did what I do best when I’m scared.

I dug into the facts.

The Defense Department archives weren’t exactly user-friendly, but Marines get good at finding what they’re not supposed to see.

After an hour of dead links and redacted summaries, I found the entry.

MAJ SARAH COLE, USMC. MIA 2003. Aircraft: MV-22B Osprey. Mission: Humanitarian extraction. Location: Eastern Ridge AO. Status: Presumed deceased. Remains: Not recovered.

Presumed.

I looked at the photograph propped against my laptop. At the coordinates stamped into metal and skin and time.

No body. No closure. Just a man in dress blues folding a flag over an empty casket.

There are some ghosts you make peace with. There are others that never quite stop rattling chains.

I’d just given that ghost a shape.

I filed an appointment request through base channels. You can’t exactly email a four-star general and say, “Hey, sir, I think I accidentally adopted your son.”

I coded my request as a follow-up on “rescued personal effects from Al-Rashir incident.” It wasn’t a lie. It just wasn’t the whole truth.

The base liaison raised both eyebrows when she saw the form. “You know you’re basically asking to walk into the lion’s den, right, Captain?”

“I’ve been in worse,” I said.

She shook her head like she’d seen enough of my kind over the years. “General Cole will see you at 0900, day after tomorrow, conference room B.”

The night before the meeting, my father showed up unannounced, as usual. He stood in the doorway, hands in his pockets, looking more like a concerned parent than a retired colonel.

“You sure you want to do this?” he asked.

“No,” I said honestly. “But I think I need to.”

He studied my face. “You remind me of your mother,” he said.

I smirked. “I thought you said that was both a compliment and a warning.”

“It still is,” he said.

Morning came too early, as it always does when there’s something heavy waiting on the other side of it.

I put on my service uniform and pressed it until every crease could cut glass. I dropped Ben at my father’s house with a kiss and a promise I’d be back before dinner.

“Marine stuff,” I told him when he asked where I was going.

He nodded matter-of-factly. “Okay. I’ll show Grandpa my new jet.”

My father caught my eye over Ben’s head. We both knew I wasn’t just going to talk about “stuff.”

The conference room was generic military: beige walls, an American flag in the corner, a table that had seen too many elbows. Coffee smelled faintly burned in the corner.

General Cole was already there when I walked in. No aides. No staff. Just him, standing by the window, hands clasped behind his back, looking out at the flight line.

“Captain Hayes,” he said, turning as the door closed. “At ease.”

I stood at parade rest, which for me is just attention with slightly less tension.

“Thank you for seeing me, sir,” I said.

“You said it concerned a recovered item,” he said. “From Al-Rashir.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

I set the folder on the table and slid the photograph toward him.

He looked down, and in that moment, the careful composure I’d seen on stage and in portraits shattered.

His hand went to the edge of the table as if he needed something to hold onto.

“Sarah,” he whispered.

He picked up the photo like it might crumble if he gripped it wrong. His thumb traced the singed edges, the curve of her cheek, the line of the pendant.

“Where did you find this?” he asked, voice raw.

“In the debris of a collapsed hangar,” I said quietly. “Wrapped around an infant I pulled from under a door. This was in the jacket with him.”

He closed his eyes.

For a long moment, I thought he might fall. Then he opened them again, and they were wet.

“You mean,” he said slowly, “he lived?”

I nodded. “Yes, sir.”

“And you brought him here,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

“Yes, sir.”

He looked at me like he was trying to reconcile the woman in front of him with the impossible facts I’d just laid down.

“What’s his name?” he asked.

“Benjamin,” I said. “Benjamin Cole Hayes.”

Something broke in his expression at the middle name. He looked away, jaw working.

I thought of my father’s warning about truths that detonate. I thought of the chaplain’s voice years ago, reading from James about orphans and widows and what pure religion looked like.

I thought of Ben’s hand reaching for mine in the dark, fingers tight around cold silver.

“I can get you DNA confirmation,” I said. “If you want. Quietly. Through the base clinic. No headlines. No lawyers. Not yet.”

He shook his head once, sharp. “I don’t need a lab to tell me what my gut already knows,” he said. “But yes. For his sake, not mine, we should do it right.”

He looked back at the photograph, then at me.

“Captain,” he said quietly, “I’ve spent years telling Marines that sometimes doing the right thing will cost them. That honor isn’t cheap and grief is the tax you pay on love.”

His voice cracked. “I never imagined anyone would pay this kind of price for my family.”

I swallowed hard. “I didn’t do it for your family, sir. I did it because there was a baby in the rubble.”

“And then you did it for years after,” he said. “Don’t you dare undersell that.”

We stood there, two Marines separated by rank and decades, joined by the strange arithmetic of war.

“We’ll do this on your terms,” he said finally. “Not mine. Not the Corps’s. His. I don’t want to rip his life out from under him just because I’ve been given a second chance I don’t deserve.”

“You do,” I said before I could stop myself.

“No, Captain,” he said. “My wife does. My wife deserves to have her boy know where he came from. The rest of it…”

He let the sentence hang.

We agreed to meet again the next morning. Neutral ground. No flags or brass or portraits watching us.

The base chapel seemed as good a place as any.

I called my father as soon as I left the building. Told him everything in a rush. The photograph. The recognition. The way the general’s voice had broken around the word “wife.”

He listened without interrupting.

“I’ll bring the boy,” he said when I finished. “And Alyssa?”

“Yeah?”

“You won’t face this alone.”

The chapel smelled like lemon oil and dust. Sunlight slanted through the stained glass, painting colored rectangles on the worn pews.

Ben sat next to my father, whispering questions about the angels in the windows. Did they wear boots? Why did one of them have a sword? Was he allowed to have a sword?

“No swords until you’re at least twelve,” I said, because some battles can be postponed.

The door opened quietly behind us.

General Cole walked in without his cover, his dress uniform replaced by khakis and a blazer. Without the armor of medals, he looked older and more human, like a man who’d lost things he didn’t know how to get back.

He stopped a few feet away.

“Ben,” I said gently, “this is General Cole. He’s a friend of ours.”

Ben stood, serious-face engaged, and stuck out his hand. “Nice to meet you, sir.”

Cole knelt to take it. His fingers shook just slightly as he closed them around the small hand.

“Nice to meet you, Benjamin,” he said. “You can call me Robert. Or sir. Whatever feels right.”

Ben considered this, then shrugged. “Okay, sir.”

He lifted his pendant without prompting. “My mom says this is a promise.”

Cole’s face crumpled. For a terrifying moment, I thought he might actually collapse.

“She would have said that,” he whispered, eyes shining.

“Who?” Ben asked.

The general looked at me, asking for permission without words.

I nodded.

“Someone I loved very much,” he said. “She wore one just like that. She flew a big plane into dangerous places to help people who were hurt.”

“Like a superhero?” Ben asked.

“Yes,” Cole said. “Exactly like that.”

Ben puffed up a little. “My mom’s like that, too. She found me when everything was broken.”

The general’s gaze flicked to me. Respect. Gratitude. Something like awe.

“She did,” he said. “She absolutely did.”

We sat together in the front pew, the four of us. A retired colonel with weathered hands. A general stripped down to his grief. A boy with two kinds of history around his neck. And me, somewhere in the middle of all of it.

I told the story again. This time not for a judge or a JAG officer, but for a man who needed to hear every detail like oxygen.

Where I’d found Ben. What the hangar had looked like. The sound of that first weak cry. The decision to bring him home.

Cole listened with his hands clasped, knuckles white.

When I finished, he took a long, slow breath.

“I don’t want to blow up his life,” he said. “He has a mother. He has a home. Whatever…whatever role there is for me, I’ll take it. And if the right thing is for me to stand back and just know he exists, I’ll do that, too.”

My father cleared his throat. “With respect, General,” he said, “you standing back never did anybody any favors.”

They looked at each other, two men who’d spent their lives carrying the weight of other people’s sons and daughters.

“Kids don’t need perfect families,” my father continued. “They need people who show up. You being here—” he nodded at Ben “—that’s what matters.”

Cole looked back at my son. “Benjamin,” he said, choosing his words carefully, “the woman who wore a necklace like yours…she was my wife. She flew a mission one day to help people far away, and her plane didn’t make it back. I thought I lost everything that day. But I didn’t know she saved something—someone—that survived.”

Ben processed this with the immense seriousness only five-year-olds and soldiers have.

“So,” he said slowly, “she helped me, and my mom helped me, and you…you’re sad.”

Cole laughed once, a short, raw sound. “That’s very accurate, son.”

Ben nodded. “You can be at my birthday,” he said, as if it had just occurred to him.

Cole blinked hard. “I would be honored.”

We didn’t make any declarations that day. No new last names. No lines drawn in legal ink.

We made something else instead.

A tiny, fragile agreement that we would all carry this truth carefully, like a candle.

A few days later, at a smaller ceremony I’d delayed for years, the base commander finally presented me with a humanitarian citation for “extraordinary compassion under fire.”

It was in a dingy auditorium, not a grand banquet hall. Folding chairs instead of round tables. A flag that had wrinkles we hadn’t quite steamed out.

I stood at attention on the stage while the colonel read the citation with the appropriate solemnity.

“Captain Alyssa M. Hayes distinguished herself by acts of humanity beyond the call of duty…” it began.

My eyes wandered to the second row, where Ben sat between my father and General Cole, swinging his feet, one hand on each of theirs.

“…demonstrating that courage is not only found under fire, but also in the willingness to bear the long-term weight of mercy…”

The applause swelled as I accepted the ribbon. It felt odd to pin official recognition onto something that had grown so personal.

“General Cole has requested to say a few words,” the colonel added, surprising me.

Cole stepped to the microphone. He wore his full uniform this time, medals catching the fluorescent light, but his eyes were the same as they’d been in the chapel.

“Marines,” he said, “we’re very good at recognizing courage that comes with blast waves and battle damage. We hand out medals for actions we can summarize in an after-action report.”

He looked at me, then at Ben.

“But some of the bravest acts don’t fit easily into a citation,” he continued. “Sometimes courage looks like hearing a cry when you could pretend you didn’t. Like signing your name on form after form because your gut says walking away isn’t an option. Like choosing, every day, to keep carrying someone else’s future even when it makes your own path harder.”

The room was still. Even the junior Marines in the back, usually fidgeting at these things, were locked in.

“This officer,” he said, voice thickening, “carried more than a wounded body out of a war zone. She carried my son.”

You could feel the ripple as the word landed. Son.

He didn’t elaborate. He didn’t have to.

“She gave him a name,” he said, “a home, a life. She gave a woman whose plane went down in the dark the one thing you hope for when you strap into a bird and take off into danger—that if you don’t make it back, someone will finish what you started.”

He turned to me, and for a second, the general disappeared. All that was left was a man whose world had shifted.

“Captain Hayes,” he said softly, “you gave my boy a second life. There aren’t enough ribbons in the Corps to cover that.”

My throat closed. I held my bearing because that’s what Marines do, but I felt tears hot behind my eyes.

The colonel started the applause, but it surged beyond ceremony. Marines stood, one after another, until the whole room was on its feet. My father stood straighter than I’d seen him in years. Ben climbed up on his chair to clap harder, cheeks flushed, pendant flashing at his throat.

Afterward, in the slow milling of people finding coffee and handshakes, Cole approached us.

He didn’t ask for anything grand.

“May I?” he asked simply, looking at Ben. “Be around. Show up. Baseball games, school plays. Days that matter. Whatever you’re both comfortable with.”

“Yes,” I said. “On one condition.”

He raised an eyebrow.

“No salutes at Little League,” I said. “And if you bring dessert, it has to be pie. We’re a pie family.”

He smiled—a real one this time, not the tight public version.

“Deal,” he said, and held out his hand.

My father took it. “Deal,” he echoed.

Two old Marines, two very different lives, shaking on a future neither of them had planned for.

Ben threaded his fingers through both of their hands like it was the most natural thing in the world.

That night, after everyone had gone home and the house had settled, I sat on the back steps with the pendant warm in my hand.

The air smelled of pine and salt. Somewhere beyond the trees, a train horn sounded—a long, low human sound that always feels like leaving and coming home at the same time.

War’s math is cruel. It subtracts without mercy. Lives. Limbs. Futures.

But every now and then, someone adds something back.

Not enough to even the ledger. Just enough to prove it’s possible.

I closed my fingers around the pendant and knew that whatever came next, we weren’t walking into it as strangers anymore.

We were what the Corps had made us.

We were a unit.

Part 5

A year slid by, not in a neat montage, but in the messy way real time moves: school days and field exercises, grocery runs and parent-teacher conferences, the occasional nightmare, the more frequent soccer game.

The official stuff wrapped up quietly.

The DNA report arrived in a plain envelope with government letterhead. I opened it at the kitchen table with my father sitting across from me, mug of coffee in his work-rough hands.

99.97% probability of paternity match: Robert Cole.

My father whistled under his breath. “That’s about as certain as God and gravity,” he said.

I stared at the paper. Even though we’d already accepted the truth in our bones, seeing it in ink did something to my breathing.

“He found his father,” I said.

“And his father found more than he lost,” my father replied.

General Cole came over that evening. No uniform. Just jeans, a flannel shirt, and a nervousness I found oddly comforting. High-ranking officers aren’t used to walking into places where nobody salutes.

I handed him the DNA report without commentary.

He read it, exhaled, then folded it once, precisely.

“Do you want a copy?” I asked.

He shook his head. “I don’t need more paper. I just need him.”

He didn’t try to change anything. He didn’t ask to move Ben across the country or put his name on any new documents.

“I missed his first word,” he said, sitting with his elbows on his knees, watching Ben push a toy truck across the floor. “His first steps. The first time he scraped his knee and realized blood doesn’t mean the end of the world. Those things are gone. I’m not going to rob him of what he has now just because my grief turned out to have a different ending than I thought.”

“So what do you want?” I asked.

He smiled faintly. “I want to be the guy in the stands who yells too loud,” he said. “The one who shows up at science fairs and pretends to understand volcano projects. The one he can call when he’s mad at you and needs someone to explain why you’re not actually the worst person on earth.”

“I don’t think that guy gets any ribbons, sir,” I said.

He looked at me. “I’ve had enough ribbons.”

Ben took to him like kids do to anyone who genuinely wants to be there. No pressure. No expectations beyond Legos and time.

They built model planes together in my garage, glue and paint turning my workbench into a miniature aircraft graveyard. Cole talked about lift and drag and how pilots measure risk. Ben talked about dinosaurs and snack preferences and how unfair it was that bedtimes existed.

My father and the general, two men who’d spent their entire lives in rigid hierarchies, gradually relaxed around each other. They argued about fishing spots instead of war strategies, about the proper way to grill ribs instead of the proper way to take a hill.

Once, I walked into the backyard to find them both teaching Ben how to throw a baseball.

“You’re dropping your shoulder,” my father said.

“You’re over-rotating your hips,” Cole said.

Ben looked at me, exasperated. “Why does everything have rules?”

“Because these two spent their whole lives following them,” I said, laughing. “You get to decide which ones you keep.”

I stayed in the Corps longer than I’d originally planned.

The war no longer needed me in the same way, but the Marines always need someone who knows where logistics meets human beings. I moved into veteran outreach, working with men and women whose scars were easier to catalog than their stories.

I visited VA hospitals with boxes of forms and boxes of donuts, helping people fill out one while they ate the other.

“Don’t leave your story over there,” I told them, whether “there” was a desert or a jungle or a dark room stateside. “Carry it with you. Let it point you somewhere. A compass, not an anchor.”

Sometimes I told them about the baby in the rubble. I never used names. I didn’t need to. They understood the pull of a mission that isn’t in any manual.

At home, life looked beautifully, almost unbelievably ordinary.

Ben learned to ride his bike on the same cul-de-sac where my father used to pace after deployments, waiting for news.

He came home from third grade with a permission slip for a field trip to the air museum. He waved it at me, eyes shining.

“Can we go, Mom? Please? General Cole says he’ll come, too. He said there’s an Osprey there like the one his wife flew.”

Something in my chest tightened—but it wasn’t pain. Not exactly.

“Yeah,” I said. “We can go.”

We stood together under the hulking shape of that aircraft a week later, the three of us. My hand on Ben’s shoulder. Cole’s hand on the railing. Ben’s fingers on the pendant.

“Was it scary?” Ben asked, looking up at the Osprey’s tilted rotors.

“The first time, yes,” Cole said. “After that, it felt like…freedom.”

“Like a rollercoaster?” Ben asked.

“Better,” Cole said.

They looked at each other and grinned, and for a moment, I could almost see Sarah there with us. Not as a ghost. As something warmer. A presence in the space between the three of us.

The base dedicated a small memorial garden beside the chapel the following summer. A place of live oaks and simple stones where people could sit and remember without having to say what, exactly, they were remembering.

The brass wanted to call it the Heritage Grove. Cole pushed back.

“What do you think?” he asked me over coffee at my kitchen table. “You’re the one who hears the cries, Captain.”

“Promise Garden,” I said, the word popping out before I even thought about it.

He cocked his head. “Why?”

“Because that’s what this all was,” I said, fingering the pendant on the table between us. “A promise somebody made in a hangar. A promise somebody else kept in a schoolhouse. A promise we’re all still trying to live up to.”

He nodded like it had been obvious all along. “Promise Garden it is.”

The dedication ceremony was small. A chaplain, a handful of Marines, a retired general and a retired colonel standing side by side, and one boy in a too-big polo shirt, his pendant shining in the morning light.

The plaque read:

FOR ALL WHO HEARD THE CRY AND ANSWERED.

Taps played soft from a single bugle. The notes curled around the live oak like a benediction.

I felt the same ache I’d felt that first night in Al-Rashir. The ache of standing in the aftermath of something terrible and realizing that somehow, against all odds, something good had survived.

After the others drifted away, I stayed behind. The garden was quiet except for the hum of insects and the distant roar of jets practicing takeoffs.

I dug a small hole at the base of the first live oak. From my pocket, I pulled out a duplicate dog tag the lab had sent with the DNA report. Sarah Cole’s name and number pressed in metal.

“Rest easy, Major,” I murmured as I covered it with soil. “Your boy’s safe. Your husband knows. We’ll take it from here.”

A breeze rustled the oak’s new leaves. If I believed in signs, I might’ve called it an answer.

That night, I came home to find Ben asleep on the couch, a half-finished model plane on the coffee table, his hand resting on his pendant like he was pressing a seal into wax.

My father snored quietly in his recliner, TV flickering muted reruns across the room. Cole had already left, a half-empty beer bottle on the counter his only trace.

“You did good, kid,” my father muttered without opening his eyes, as if he could sense where I’d been.

For once, I didn’t argue.

Years will keep passing. That’s what they do.

One day, I’ll stand in a different auditorium and watch Ben—taller now, voice deeper, shoulders squared in a way that makes my chest ache—make his own choices.

Maybe he’ll put on a uniform. Maybe he’ll pick up a guitar. Maybe he’ll fly planes like the woman who gave him life or heal people like the medic who kept him alive in that schoolhouse.

Whatever he chooses, he’ll do it knowing where he came from.

Knowing that his story started with a cry in the ruins and continued because a whole chain of people refused to walk past it.

When I talk to new recruits now, or to veterans whose stories are eating them from the inside, I don’t always talk about battles.

Sometimes, I talk about that night in Al-Rashir. About the sound of a baby’s cry coming from under a slab of concrete. About the way everything else in the world went quiet in the face of that sound.

I don’t mention four-star generals or DNA tests. I don’t need to.

I tell them this instead:

“Someday, you’ll hear something only you can hear. A scream. A sob. A plea nobody else is close enough—or willing enough—to answer. It might be in a war zone. It might be in a barracks room or a grocery store parking lot or a phone call at midnight. It might sound like a baby. It might sound like your own voice.

Whatever it is, don’t walk past it just because it’s not in your orders.

Sometimes, the cry you answer isn’t just theirs.

It’s your own.”

If this story has a moral, it’s not about medals, though the Corps will always find ways to pin metal to cloth.

It’s about what you decide to carry when the shooting stops.

About whether you let the world harden you into something unbreakable and useless, or whether you allow a crack or two so the light can get in.

I used to think honor was about who saluted you.

Now I know better.

Honor is about who you bend down to lift from the ashes.

And if you listen, really listen, you’ll hear them.

Crying in the rubble. Laughing in the living room. Asking hard questions in the garden.

That’s where the real battle is.

That’s where you decide who you’re going to be.

I chose a baby in the ruins.

He chose me back.

And somehow, in all that brokenness, a family was born.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

I Thought the Iron General Would Destroy Me — But When He Saw My Dad’s Old Coin, He Started to Cry.

I Thought the Iron General Would Destroy Me — But When He Saw My Dad’s Old Coin, He Started to…

At the General’s Will Reading, the Lawyer Suddenly Asked Me: “Do You Know Your Parents?”

At the General’s Will Reading, the Lawyer Suddenly Asked Me: “Do You Know Your Parents?” At the General’s will reading,…

Take Off Your Uniform — Commander Ordered Her, Then She Smirked, You Just Did The Biggest Mistake Of

Everyone in the base thought she would break. Everyone thought she would obey. But Lieutenant Mara Hale did something no…

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off …

I was rushed to the hospital in critical condition. The doctors contacted my parents, but they said, “We can’t, our other daughter is busy walking her dog.”

I was rushed to the hospital in critical condition. The doctors contacted my parents, but they said, “We can’t, our…

My son left me off the wedding guest list but sent a $90,000 invoice for the party and honeymoon, joking that I should be grateful to chip in. I quietly set things in motion to flip his dream on its head.

My son left me off the wedding guest list but sent a $90,000 invoice for the party and honeymoon, joking…

End of content

No more pages to load