I paid my parents $700 a week hoping it would buy peace. But when they skipped my daughter’s birthday and said, “Your child means nothing to us,” everything inside me broke.

Part I: Mondays at 9:00

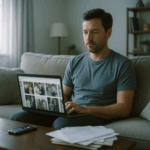

Every Monday at 9:00 a.m., I sent seven hundred dollars to my parents without fail. It was an act with choreography: brew coffee, wipe last night’s crumbs from the table, pull my scrub top over tired shoulders, set the laptop in front of Ava’s rainbow drawings taped to the wall, and type the same numbers into the same fields. Routing. Account. Amount.

“Payment sent,” the confirmation would blink in the corner like a heartbeat.

I told myself it was a kindness. Some weeks I told myself it was an investment in peace. On the worst weeks I admitted quietly—never out loud—that it was penance for existing in a way they never asked me to. Penelope the Disappointment, the girl who left and came back with a baby and a badge that said Registered Nurse and a spine that kept trying to stand up in rooms where slouching was the law.

Ava would spin in the living room while I hit submit. “Mama, look! Spinny skirt!” she’d cry, her glittery tulle catching the kitchen light. She thought her grandparents lived Far, capital F, a place off the edge of maps. Not thirty minutes cross-town. She believed me when I said “Maybe next time, sweetheart,” because kids believe what you hand their hearts, and I kept handing her maybe.

Their bills arrived like weather. My mother texted me like a manager, brisk and precise: Grocery total is $146.82. Add your father’s cholesterol medicine. Your father’s car needs a new battery. She never thanked me—gratitude was tacky, she said once, as if please and thank you were coupons for people who hadn’t learned better. My father rarely texted at all. When he did, it was a thumbs-up or a question mark or a misspelled “ok,” like we were coworkers navigating a shift change.

Still, I paid. When their power bill was overdue, I covered it before they could hint. When their car died, I paid the mechanic. My friends set money aside for trips and kitchen tables; I bought my parents another month of quiet. Peace on layaway. Seven hundred dollars at a time.

Part II: The House That Wasn’t Ours

The first real crack wasn’t a sentence. It was a photograph—a stranger in a beige coat in my parents’ driveway, a camera slung around her neck.

“Hi there!” she said, like she’d been waiting to be welcomed for months. “Here to shoot the listing. Sun’s great today.”

“The listing?” I repeated, literal because figurative would make me spit.

“For the house,” she said cheerfully. “The agent sent me.”

I stood there holding a bag of canned tomatoes, lemons rolling to the bottom like a plot twist. “They’re selling?”

She flipped her clipboard. “Address checks out. Congratulations.” Then she lifted the camera and started capturing walls I’d kept upright with overtime.

That night I asked them why. My mother took a sip of tea and said, “We need a new start,” as if starting over were a sweater she’d found on sale. My father said, “We don’t want to be beholden to you,” as if the word beholden were a trap and I had laid it.

“They’re my payments,” I said. My voice didn’t crack. It calcified. “You’ve built your new start on my money and my Monday mornings.”

“We didn’t ask you to,” my mother replied, with the defiant innocence of a child caught stealing cookies and insisting they were hungry. “You insisted.”

Here’s the truth: I had insisted—because guilt is a lever anyone can pull and hope is the fulcrum that never moves. I had sent money because I am exactly the kind of person who believes family is a verb, not a noun. They took it because they are exactly the kind of people who confuse help with obligation.

The next morning I brewed coffee at 8:58 a.m. and still sent the seven hundred dollars at nine. Because habit is a god that doesn’t care if you stop believing.

Part III: The Birthday

For Ava’s sixth birthday, I tried to build a memory that could survive the winter. Streamers from the dollar store. Lemonade in mason jars. A secondhand bounce house I found for fifty bucks and a favor. Her hair braided like Elsa, her cheeks pink with the velocity of joy. She kept checking the gate.

“Do you think they’ll come this time, Mommy?” she asked, peering at the street between guests, careful not to step on her own excitement.

“Maybe, baby,” I said. “Let’s wait a little longer.”

By three, the candles had melted into soft pink puddles and the lemonade had the warmth of regret. Ava watched the road like faith could parallel park. She held her cupcake and didn’t eat it. Her sparkly shoes dangled over the porch step like swinging reasons.

“Maybe they forgot,” she said finally, voice correct and small.

“Maybe,” I said, and kissed a forehead that didn’t deserve a lie. “We still had fun, didn’t we?” She nodded, the way kids nod when they decide they’ll let you pretend a little longer for your sake, not theirs.

After cake and the calculus of goody bags and the bounce house wheezing itself flat, I scrolled through photos on the couch. In every one Ava is smiling like sunshine in a jar. In the corner of the screen, a text from my mother: Tell Ava happy birthday from us. No punctuation. A sentence that took nothing and cost less.

I called.

“Why didn’t you come?” I asked when my father answered. No pleasantries, no softball. We had graduated beyond the need to pretend.

“We didn’t feel like it,” he said.

“Dad,” I said, finding the calm that lives under the river, not on top. “She waited for you.”

There was a rasp, the sound of pride clearing its throat to lie. Then he said it: “Your child means nothing to us.”

Silence was the only thing I could afford. My ears filled with refrigerator hum like I’d moved into a new country where appliances are cruel. The phone was still pressed to my cheek when I realized he had hung up.

I went to Ava’s room. She was asleep, one hand still covered in glitter, her mouth open in an O like wonder had learned to breathe out of it. I kissed her forehead and whispered, “You’re everything.” Not to her—she was dreaming—but to the part of me that needed to say it out loud before I forgot my own language.

Then I went to the kitchen, set my phone on the counter, and watched the clock breathe past nine p.m.—a different nine than the one I used to serve.

Part IV: Strings, Cut

I didn’t sleep. I sat at the table and let his words sit across from me like a terrible guest I refused to feed. At midnight, I opened my banking app. The recurring payments lined up like obedient soldiers: rent, utilities, groceries, auto. The weekly transfer to my parents. I canceled them one by one, a guillotine with a touchscreen. Click. Confirm. End.

When I reached “Automatic transfer: $700, Weekly, Monday, 9:00 a.m.,” my thumb hovered. My hand trembled, then stilled. I canceled that one too.

For a moment, the room made the sound of a refrigerator in a house that belongs to you. Then my phone buzzed.

Can you order us dinner? my mother texted. Nothing fancy, just Chinese or something. We don’t have food in the house.

Forty minutes. That’s how long it took for them to notice I had stopped paying for their life. Forty minutes after my father erased my daughter, my mother asked me to buy her lo mein.

I locked my phone and slid it face down on the counter. I walked to Ava’s room, sat on her bed, and placed my palm over her small ribs to feel her breathing. “Never again,” I whispered. Not to them. To me.

Part V: Fallout in Real Time

Morning arrived like an insult. Sun on the table, coffee staining the same ring as yesterday. An unknown number called. It was their landlord.

“Ms. Hayes, this is Richard. The rent didn’t come through. Is everything alright?”

“Everything’s fine,” I said, and the words surprised me with how true they tasted. “It’s not my responsibility anymore.”

“They told me you managed their payments,” he said.

“I used to.”

I hung up and felt the cord snap. Not the one connecting me to them. The one connecting me to the idea that I owed them rescue.

At ten, my brother called. “Pen,” he said, “Mom says you’ve lost your mind.”

“Define lost,” I said.

“She says you’re cutting them off.”

“I am.”

He was quiet for a heartbeat. “Good. I’m done, too.”

“What?”

“I’ve been sending them two hundred a month,” he admitted. “Groceries. Gas. Little things. I thought if we both…” He didn’t finish.

“They never told me,” I whispered.

“They never told me about you,” he said. “Guess we were paying rent on the same guilt.”

We laughed at the absurdity, and the laugh turned into something like grief. Not for them. For the time we had spent buying a version of family that didn’t exist.

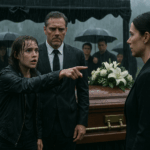

A notification popped. “The Truth About Our Daughter,” a Facebook live replay. My mother clutching a tissue like it was a prop, my father’s arms crossed, jaw set.

“We’ve always supported Penelope,” my mother sniffled. “But she’s made up lies, telling people we refuse to see her child.”

“She’s been forcing money on us for years,” my father said. He actually had the nerve to look wounded. Then he held up a printed photograph of Ava in her pink dress and said, “This child does not exist to us.”

I threw my phone on the couch—then picked it back up. I closed the video. Within an hour: Are you seeing this? Is that your dad? My cousin Lauren texting, Do. Not. Post. Anything. Let them choke on their own words.

I obeyed. I learned silence is a language, and mine was becoming fluent.

By evening, the video had spread through town. Church friends shared it with prayer hands. Strangers asked what kind of grandparents say that about a six-year-old. By morning, their church had quietly removed their photo from the website like sin could be deleted with HTML.

Two days later, Lauren called. “They showed up at the family reunion,” she said. “Telling everyone you’re lying.”

“I didn’t go,” I replied.

“I know. But you might want to look at Facebook.”

An hour later, a video from a different phone: a sunny backyard, plastic cups, folding tables. My mother pleading, “No matter what Penelope told you, we love her. That poor child—she’s confused.”

And Lauren, like a blade: “Before or after you said her kid doesn’t exist?”

Someone held up a phone to a speaker. Out came my father’s voice: Your child means nothing to us. Collective silence. Then Uncle James, steady as a table: “If that’s how you treat your granddaughter, you don’t belong here.”

No one argued. No one hugged them. They left with eyes down, like children told to clean up a mess they pretended they didn’t make.

I watched it three times. Then I laughed, quietly and from a deep place. Not cruel. Released.

Part VI: Thirty Days

Richard texted, “They’ve been told to vacate in thirty days. I’m sorry it came to this.” I didn’t respond. Not because I didn’t have words. Because the only honest sentence I had was already complete: This is not my fire to put out.

The video kept moving. Church pages writhed and reorganized. Someone clipped together both clips—their live performance and their public undressing at the reunion. The comments turned, tide-like and swift: Hypocrisy at its finest. You can’t erase your own blood. That poor little girl.

I posted nothing. I did not dance on their digital grave. I took Ava to the park. She drew stars with chalk and named them after people she loved.

“This one’s for Uncle Ryan,” she said, starburst messy and bright.

The sky smelled like rain and possibility.

Back home, I found an envelope in the mailbox, cream paper, my name in Aunt Virginia’s careful hand. Inside was a single sentence: They chose pride. You chose your child. That’s what family is supposed to look like.

I folded it and put it in a drawer next to Ava’s first tooth, the hospital bracelet that once circled her wrist like a question, and the last photo of me with both my parents that doesn’t make my stomach turn. The drawer felt like a museum that allows only honest exhibits.

That night, Ava asked, “Mommy, can Nana and Grandpa come next year?”

“No, baby,” I said. “They won’t be coming anymore.”

She thought about it, the way kids think in full color. “That’s okay,” she said. “We can invite Uncle Ryan.”

“Yes,” I said. “We can.”

Part VII: Boundaries, with Flowers

The following week, the noise fell away. Their profiles vanished. Their church issued a statement about healing and boundaries, which in church-speak means someone did something unforgivable and there are potlucks to be scheduled without them. I didn’t feel victorious. I felt free. The kind of freedom that sits in morning sunlight with you and doesn’t ask for anything back.

Ryan showed up with groceries and a grin that reached his eyes. “You look lighter,” he said.

“Maybe I am,” I replied. “How’s your guilt budget?”

“Retired,” he said, and we clinked coffee mugs like crystal.

We drove to Aunt Virginia’s for Sunday lunch. Lemon pie cooling on the counter. Sun through lace curtains. She hugged Ava, then hugged me, then put her hands on my shoulders and said, “Peace looks good on you.”

Over pasta she talked about boundaries: how love without respect is appetite; how saying no is a full sentence; how forgiveness sometimes looks like letting people meet the consequences they spend their lives outrunning. “Kindness with boundaries is strength,” she said, and later, when she slipped an envelope into my hand, that sentence was written on a card in her cursive.

That night I watched Ava sleep, her small chest rising under the soft light of her nightlight, and realized the quiet wasn’t empty anymore. It was protection. It was mine.

Part VIII: The Long Clean

Cutting them off set off a chain of small domestic miracles. I deleted old reminders from my phone and replaced them with new ones: Kindergarten registration. Dentist appointment. Buy new sneakers before Growth Spurt Season. I updated my budget spreadsheet. The “Parents” row—once a long red line across columns—wasn’t there. The blank space felt like a window.

I signed us up for a Saturday ceramics class. We made lopsided bowls that a less generous person would call ashtrays. Ava made a snake that looked like a question mark, then painted it purple and named it Dorothy. At home, we planted basil in a pot and put it on the kitchen window sill. We named the basil, too. “Hope,” Ava decided. “Because it helps things taste better.”

Sometimes my phone buzzed with unknown numbers. I let them go. Richard called once more to say the locks had been changed. I thanked him for being kind and moved a pile of laundry without the guilt of a stranger’s problem in my hands.

The hospital offered me a day shift. I took it. Suddenly the world had evening. We ate dinner at a table at an hour the sun still noticed. Ava learned to help without turning it into a report card. I learned to sit.

Part IX: The Letter I Didn’t Send

I drafted a message to my parents, a long one. I didn’t send it. It contained the things I would have said if I had needed them to know. It started with “Your granddaughter has a gap tooth now, the way I did when I was six, and she laughs the way you must have when you were young, Mom, before you learned to swallow your voice and then spit it as orders.” It contained the sentence “You taught me that love is a bill you pay on time or else,” followed by “You were wrong.” It ended with “I hope someday you understand that the only thing you successfully cut out of your life was the part that would have forgiven you.”

I printed it, folded it, slid it under the card from Aunt Virginia. The drawer closed like a boundary gently locking.

Part X: The Call from the Church Lady

Two months later, a woman from their church called. “We’re praying for reconciliation,” she said.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Would you be open to a mediated—”

“No,” I said. “I am not available to protect two adults from the consequences of their own speech.”

“That’s not—”

“It is,” I said, and hung up. I stood at the sink and washed basil leaves like sins I decided not to commit.

Part XI: The Reunion We Didn’t Attend

A new family reunion arrived on the calendar, the kind printed without shame from a spreadsheet someone keeps in a drawer beside recipes. Lauren texted, “You’re welcome to come. Or not. Either way, you’re family.” We didn’t go. Not because I was punishing anyone. Because I had promised Ava the science center would teach us how to be astronauts for a day and promises to her count more.

We built a paper rocket and launched it in a room full of kids and parents and grandparents who knew how to show up. I felt a pang and then a warmth that washed it—my body learning that memory can be fed without starving the present. Ava’s rocket hit the ceiling tiles. She squealed. For a second the sound filled every space in me that used to be apology.

Part XII: The After

Months unspooled. The Facebook group found new scandals. The church lady moved on to casseroles. My parents, as far as I could tell, vanished into the lattice of people who choose pride and call it privacy. That was their right. Silence belonged to me, too.

On the anniversary of the night my father said the sentence that carved a new life into me, I sat at our kitchen table at 9:00 p.m. on purpose. The clock ticked past the hour. No transfer. No confirmation. The laptop reflected my face back to me. I looked like a person who had finally set a bag down.

Ava padded into the kitchen in pajama feet. “Mama, can I have water?”

I poured some into a cup decorated with purple bunnies and handed it to her.

“Do you think we can have a big bouncy house again on my birthday?” she asked, drinking.

“We can,” I said.

“Can we invite Uncle Ryan and Aunt Virginia and… me?”

“Especially you.”

She grinned. “Good night.” She hugged my waist and toddled back to bed.

I turned off the light. The basil on the sill smelled like summer in a small, defiant way. I stood in the darkness and listened to the house breathe. It sounded like peace. Not loud. Not triumph. A steady, earned hum.

Part XIII: A Year Later

We threw another party. Streamers, lemonade, the better bounce house because I found it cheap in a yard sale group. Ryan manned the grill like a man who had been practicing telling the truth and discovered it tasted better than lying. Aunt Virginia taught kids how to blow bubbles with their hands, her laugh ringing like bells in chapel. Ava wore a yellow dress and kept her eye on the gate, but not in that old way. She watched for the people we invited—the ones who have proven they belong.

When the candles went out, she wished on smoke.

“What’d you wish for?” Ryan asked.

“I can’t tell,” she said, solemn. “Or it won’t come true.”

“Fair,” he said.

After everyone left, we sat on the porch steps. The street was quiet. The sky turned that particular bruised blue that happens right before it lets go completely.

“You did right,” Ryan said.

“I did what I had to,” I said.

“Same thing.”

Across the lawn, the headlights of a slow car brushed the curb. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t rise. I didn’t prepare a speech or a barricade. The car kept going. We laughed at ourselves because we could.

Inside, I washed plates without thinking about seven hundred dollars. Ava fell asleep holding Dorothy the purple snake. I set a slice of cake aside for breakfast because joy is better when it leaks into the next day.

Before bed, I opened the drawer, took out Aunt Virginia’s card, and reread the line I now knew by memory: Kindness with boundaries is strength.

I tucked it back. I slept.

Part XIV: The Ending I Chose

This is the part people always ask about: Did they ever apologize? Did they come around? Did the church make them confess on camera? Did they, did they, did they.

No.

They chose pride. I chose freedom. That’s the story. It doesn’t have to be more dramatic than that line. It is dramatic enough.

Freedom looks like breakfast without dread. It looks like a budget without a row titled Parents. It looks like a little girl who doesn’t keep checking the gate. It looks like a woman who can sit at her own table and feel the centrifugal force of peace pull everything that matters to the center while letting the rest fly off into whatever galaxy finally has room for it.

On Monday mornings at nine, I still open my laptop. I pay rent. I pay the electric bill. I send money toward a small vacation fund we call Somewhere With Water. I send seven dollars to my own account labeled Fun, because sometimes the number matters less than the message.

Payment sent, my screen blinks. Not to them. To us.

I close the laptop, and Ava spins in her still glittery skirt, and the basil on the sill will need water, and the house hums like a living thing that intends to keep doing it.

Everything inside me broke. Everything I needed stayed. And the life we built afterward fits like it was made for us. Because it was.

Part XV: The Grocery Aisle

Two weeks after the party, Ava and I were in the grocery store arguing with a melon. She knocked it with her knuckles the way Aunt Virginia taught her and pronounced it “hollow like a drum.” We were still laughing when I turned a corner and nearly collided with my mother.

She froze. Her hand, already reaching for a carton of eggs, hovered as if she’d been unplugged mid-motion. For half a second, I was eight again, scolded for breathing too loudly. Then I remembered I was the woman who had ended a war without picking up a sword.

“Penelope,” she said.

“Mom.”

We stood in the fluorescent light with canned tomatoes watching from the shelves. She looked smaller, like the world had finally changed its mind about cushioning her fall. She opened her mouth, closed it, tried again.

“I wanted to—” she started.

Ava barreled into the cart with the kind of momentum that only exists in bodies that haven’t learned to be careful yet. “Mama, can we get the cereal with the tiny marshmallows?” she asked, not seeing my mother, or maybe pretending not to, which is its own sort of grace.

“Not today,” I said gently. “We’re getting the one that doesn’t taste like regret.”

My mother flinched at regret the way people flinch at sudden light. “She’s grown,” Mom said, gaze flicking to Ava, then flitting away like it was dangerous to make contact.

“She has,” I said. “She reads chapter books now. She makes up songs. She names plants.”

Silence stretched. Somewhere near the bakery, a child started crying for a cookie and was offered a carrot instead, which made the crying louder. Life continued, indifferent.

“I wrote you a letter,” my mother said abruptly.

“You did?” I asked. Not unkind. Not too kind. A tone I’d learned in the last months: neutral doesn’t mean numb.

“I didn’t send it.” She looked embarrassed. “I… couldn’t find a stamp. And then I didn’t know if stamps were the problem.”

“Stamps rarely are,” I said.

Ava tugged on my sleeve. “Mama, can we go see the lobsters? I want to name them before they’re soup.”

“Two minutes,” I said, then turned back to my mother. “We have to go.”

“Penelope,” she said quickly. “I… I’m sorry.”

For what? hovered on my tongue. It would have been a battlefield question and I was done with war.

“Thank you,” I said. “We’re leaving now.” I took the cart handle and steered toward the tanks where lobsters blinked anciently at fluorescent futures. Ava pressed her hands to the glass. “This one is Sir Pinches,” she decided. “He’s a knight.”

We left with cereal that told no lies and a basil plant that needed more light than our kitchen could reasonably offer but that Ava insisted on rescuing anyway.

In the car, she asked, “Was that Nana?”

“Yes.”

“Is she still mad at you?”

“No,” I said, surprising myself by believing it. “She might be mad at herself. That’s not ours to fix.”

Ava hummed, satisfied. “Good. Because I’m busy naming lobsters.”

Part XVI: Fire Drills

When you build a new life, you test its exits. I wrote contingency plans like some people write poetry—just in case. If I get called in for an emergency shift, who picks up Ava? (Ryan, Aunt Virginia, Mia; a calendar with three names is steadier than one with one.) If Ava gets sick at school, where do we keep the thermometer and the soup and the stories? (Top cabinet, bottom shelf, the blue book with the rabbit who learns bravery isn’t loud.) If my parents show up at our door? (We don’t open it. Not because we’re cruel. Because we’re safe. I wrote a script and taped it inside the closet door: We are not receiving visitors. Please leave.)

I taught Ava how to call 911 without making it a game. “We only press these numbers when grown-ups can’t help,” I said. “And we never press them to see what happens.”

“What happens?” she asked.

“People who know what to do show up,” I said. “But only if we need them.”

“Like Uncle Ryan,” she said seriously.

“Exactly.”

Ava practiced fire drills with a stuffed bear named Captain. We crawled low under imaginary smoke and met by the lamppost and counted to make sure everyone made it. “Safety is boring,” she proclaimed after the third drill, flopping dramatically on the grass.

“Boring is good,” I said. “Boring is where peace lives.”

She considered this. “Then I like boring.”

Part XVII: The First Report Card

In late October, Ava brought home a report card with stickers and checkmarks in boxes that told me she was a person who tried, and tried kindly. Her teacher, Ms. Ortiz, wrote, “Ava asks great questions and helps other students sound out words. She reminds me to breathe.” I cried a little in the parking lot. Not because of grades. Because of the sentence about breathing. It felt like proof that our house had not stolen something essential from her.

At pickup, Ms. Ortiz pulled me aside. “I know you work nights sometimes,” she said. “If you ever need me to hold Ava for ten minutes until someone arrives, call the office. We’ll sit in the library and pretend to be quiet.”

“Thank you,” I said, swallowing a windfall of gratitude. In the car, I told Ava we were getting ice cream to celebrate her report card.

“I didn’t even do anything,” she said, delighted and suspicious.

“You exist,” I said. “That’s everything.”

She chose strawberry with sprinkles. I chose vanilla because you don’t have to make complicated choices to prove you’re enjoying yourself. A woman at the next table smiled at us. “You two look like peace.”

“We’re practicing,” I said.

Part XVIII: The Winter Parade

Our town has a winter parade that is mostly trucks wrapped in lights and teenagers attempting choreography from the back of flatbeds. It is earnest and a little chaotic and exactly what community looks like when it’s trying hard for the right reasons.

Ava and I bundled up and stood with Aunt Virginia near the bakery to watch. We drank hot chocolate that could scald a saint and waved at Santa like we were still on his list. In the distance, a small group from my parents’ church marched past with a banner about joy.

My mother wasn’t there. My father wasn’t either. For a moment, I felt phantom guilt like a draft under a door. Then a group of middle schoolers shuffled past dressed as snowflakes—cardboard, glitter, conviction. One lost a mitten. Ava darted forward and handed it back, solemn as a paramedic. The snowflake grinned. The moment passed. The rest of the parade was ours.

On the walk home, Ava slipped her hand into mine. “Mama?”

“Hmm?”

“Joy is loud,” she said, thinking of the banner.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Sometimes it’s quiet like hot chocolate.”

She nodded. “I like both.”

Part XIX: Ryan’s Confession

In January, Ryan sat at my table and confessed that he’d been going to meetings.

“I go because I thought addiction didn’t apply to people like us,” he said. “Turns out it doesn’t care about like us.”

“I’m proud of you,” I said, and meant it.

He scratched at a knot in the wood with his thumbnail. “I kept thinking if I gave Mom and Dad enough money, they’d like me more. Like there was a cover charge for their approval.”

“We both thought that,” I said.

He smiled a little. “Now I’m saving for a down payment on a house that smells like my cooking.”

“You should make a list of everything your house will have that you never had growing up,” I suggested.

“Okay,” he said, and started writing on the back of a receipt.

A door that locks and no one yells through it.

A couch anyone can sit on without being judged for where they sit.

Enough forks.

He looked up. “Enough forks,” he repeated, and we laughed until Ava came in from the living room asking if this was a fork party and where was her invitation.

Part XX: The Envelope

A certified letter arrived in late February. The return address was their church. I opened it at the counter with the wary respect you give to official paper. It wasn’t from the church. It was from my father. He had used their letterhead like a disguise.

Penelope,

We’re moving to a different town. Smaller. Don’t worry. We’re not asking for help. I wanted you to know we saw a therapist. She asked me what I meant when I said Ava didn’t exist to us. I couldn’t answer. She asked me who taught me to speak like that. I could answer that. My father. His father. Men who thought control is love and love is leverage. I don’t know how to fix how I spoke and what it did. I want to try. If you ever want to talk, I’ll be here. If you never want to, I accept that, too.

Dad

I held the letter and felt something tired lift a little. Not forgiveness. Not yet. An uncoiling, like a spring I didn’t know I’d wound waiting to see if he’d ever write something worth reading. I didn’t reply. But I didn’t throw it away. I put it in the drawer with Aunt Virginia’s card. The drawer was becoming a museum of possible futures.

Part XXI: The PTA Meeting

I went to a PTA meeting because I am the kind of woman who swore she’d never go to PTA meetings and then discovered they are where the field trips get funded. A woman with a type-A haircut argued that the bake sale should be gluten-free to “attract a wider donor base.” A man suggested a car wash in February. Ms. Ortiz, who apparently doesn’t sleep, volunteered to coordinate both.

I raised my hand. “I’m good at spreadsheets,” I said. “And shifts.”

“Bless you,” Ms. Ortiz said, which felt like a sacrament.

After the meeting, a woman with kind eyes approached. “You’re Penelope,” she said. “I’m Marla—my kid’s in Ava’s class. We heard what happened with your parents. People talk. I hope you don’t mind me saying: you did the brave thing.”

“The necessary thing,” I said.

“Same,” she replied, and handed me a Tupperware of brownies because some people understand that solidarity is also sugar.

Part XXII: The Dance Recital

Spring came with clouds that couldn’t decide and a recital that could. Ava’s class wore yellow skirts that gusted like dandelions. We sat in the auditorium and watched small humans struggle adorably to find beat. When Ava found me in the crowd, her face lit like the stage had stepped closer.

After the bows, her teacher handed out flowers. Aunt Virginia had brought roses and one crooked tulip from her yard that Ava declared “my favorite because it knows how to tilt.” Ryan wiped his eyes like men who grew up being told not to.

In the lobby, a woman asked, “Is your mother coming?” and for a second I thought she meant mine. “No,” I said, and didn’t feel the sting I expected. “We have the right people here.”

Ava handed a flower to Ms. Ortiz. “For reminding my mom to breathe,” she said solemnly.

“You remind me,” I whispered.

“Always,” she said, because we had taught each other our lines.

Part XXIII: The School Project

Ava’s class had to make family trees. I considered forging jury duty so we could skip it. Instead, we sat at the table with markers and glue and the words we own.

“Who should I put here?” she asked, pointing to a branch where grandparents traditionally loiter.

“Who shows up?” I asked.

“Uncle Ryan,” she said, scribbling his name with hearts. “Aunt Virginia.” She drew a small basil leaf and wrote Hope because she’d decided plants counted.

“And here,” she said, holding up a glue stick with a dramatic flourish, “Mama.”

She put us at the trunk and didn’t ask if that was allowed. I didn’t tell her family trees are supposed to have more branches. I let ours grow the way it wanted.

The next day I saw her tree on the bulletin board outside her classroom. A group of kids stood pointing and comparing. “Your family is small,” a boy said to Ava, matter-of-fact.

“My family is enough,” she said, and the boy nodded like he appreciated the efficiency.

Part XXIV: The Laundry Room

There is a small laundry room in our building with a bulletin board that used to be for lost socks and is now for everything: babysitter numbers, a book exchange, a flyer for free yoga from someone who looked limber enough to be untrustworthy. One afternoon I found a handwritten note tacked up:

If you need help with rent or groceries this month, text me. No questions. – Apt 2D

I didn’t need help. But I ripped a corner of an envelope and wrote underneath:

If you need help with CPR or stitches, knock on 4C. RN. No questions.

Someone drew a heart. Someone else added: Forks, if you’re out for a party. 3B.

A micro-community, built without a group chat. It felt like proof that generosity can exist without being a trap.

Part XXV: The Storm

In August, a thunderstorm rolled in the way men some of us dated used to: hot, thinking it was a gift, intending to make a mess. It downed a power line on the block and the building went dark. I grabbed the flashlight and has anyone seen my phone? and the battery pack I keep fully charged because the part of me that worked nights knows better.

In the hallway, people had their doors open to let air move. Mr. Whitaker from 3B offered up extension cords like sacrament. The teenager from 2D played acoustic guitar quietly and Ava sat on the threshold, listening with the reverence small people reserve for people who won’t talk down to them.

By candlelight, I told Ava the story of how we got here. Not the bloody parts. The bravery: how we chose us. How sometimes choosing us sounds like no. How no can be a lullaby.

“The lights will come back,” she said.

“They always do,” I said, and meant more than electricity.

Part XXVI: The Church on the Corner

I hadn’t passed their church for months. One Sunday, traffic rerouted us past it. The banner out front had a new slogan about grace. The front lawn had a lemonade stand manned by a child with a glitter sign. I bought a paper cup for a dollar. It was sour and perfect.

The pastor stood under a tree talking to an old man about God and probably also about weather because the two share a committee. He didn’t see me. Or if he did, he chose to let me pass unharassed. I appreciated the effort it took to do nothing.

Back in the car, Ava asked if God lives in buildings.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Sometimes God lives in boundaries.”

“What’s a boundary?”

“A line that keeps the right things in and the wrong things out.”

She drew a line with her finger on the fogged window. “Like this?”

“Exactly.”

Part XXVII: The Call I Took

A year and a half after the birthday, my phone rang with a number I recognized and didn’t fear. My father.

“Hi,” I said. Heart calm, breath even.

“Hi,” he said. “We moved. It’s… small. But ours.”

“I’m glad,” I said, and was.

“I volunteer at a community center,” he said, and laughed self-consciously. “Turns out I know how to fix things besides my pride.”

“That’s good,” I said.

He cleared his throat. “I don’t expect anything. I just wanted you to know.”

“Thank you.”

“Will you tell Ava happy birthday?” he asked, voice steady.

“I will,” I said.

We said goodbye. He didn’t say sorry again. He didn’t ask for a door. He told me something I was free to put down if it was too heavy. I held it. It was light.

Part XXVIII: The Second Birthday

We threw another party. Different streamers. Same lemonade. The better bounce house because this time it was a choice, not a fix. The people who came were the ones who had been coming, plus a boy from Ava’s class who brought a stick bug in a jar as a gift and made me question the wisdom of letting strangers bring live things into my home. Ava named it Sir Sticksalot and declared him “family for today.”

When the last kid left and the yard had returned to grass plus confetti, Ava hopped onto the porch step and cleared her throat like a town crier.

“Announcement,” she said. “Next year we will have a piñata.”

“Noted,” I replied. “Requirements?”

“It will be shaped like a basil plant,” she said.

I laughed. “We’ll see.”

After she fell asleep under a blanket that had somehow acquired star stickers, I sat on the porch with a slice of cake and listened to the neighborhood. Somewhere, a couple argued gently about who left the hose on. Somewhere, a dog barked as if the moon had insulted it. Somewhere, a woman poured herself a glass of something and decided tomorrow would be kinder. The air didn’t know me. It cupped my face anyway.

Part XXIX: The Hospital Hallway

A patient coded on a Tuesday. We did what we do: we counted compressions, we shouted meds, we asked walls to hold for one more minute. We didn’t save him. I washed my hands under water that had become its own kind of prayer and stepped into the hallway and cried in the way nurses do: for the tiniest bit of time, deeply, then not at all—because there is charting to be done and other lives to hold up.

An older nurse—Sharon, who has the posture of someone who carries hospitals across rivers—handed me a tissue. “You have a kid, don’t you?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“How old?”

“Six,” I said. “Almost seven.”

She nodded like this was a code she could read. “You going home after shift?”

“Yeah.”

“Good. Let her tell you something dumb. Laugh too hard. It’ll put the floor back under your feet.”

I did. Ava told me a joke about a tomato that wasn’t funny until she started laughing and then it was vital. I laughed so hard I scared the basil plant and we both agreed that was medicine.

Part XXX: The Finale—A Letter to Future Ava

On the night before she turned seven, I wrote a letter and tucked it into the book she asks me to read when she’s brave: the one where the rabbit learns to sleep without the light and learns the dark is full of things that are not teeth.

Ava,

You will ask someday why we don’t have pictures of you with them. No, not them. With Nana and Grandpa. I’ll tell you the truth: they taught me that money is the same as love, and I taught them it isn’t. They were wrong loudly. I was right quietly. That quiet is why you sleep without waiting for a car that never parks.

If you ever forget your worth, I will remind you with the evidence of breakfasts and bedtime stories and all the Mondays we didn’t buy peace—we made it.

If you ever think your job is to keep anyone calm, remember: you are not a savings account for someone else’s regret.

If you ever meet a boy or a girl or a person who thinks boundaries are meanness, introduce them to a door.

You are my yes. You are my enough.

Love,

Mama

I slid the letter into chapter three, where the rabbit realizes the closet is not a monster; it’s where the costumes live.

Then I turned off every light in the house but one. I stood in the doorway of Ava’s room the way I have since the night she was born, as if my silhouette could keep watch. She murmured in her sleep, rolled over, took the blanket with her.

Outside, the world kept doing what it does. A siren wailed and faded. A sprinkler did that annoying tt-tt-tt, and then the longer shhh that sounds like the summer doing percussion. Somewhere, my parents were learning how to pay bills without using my wrists. Somewhere, a church lady used the word reconciliation and meant submission; somewhere else, someone folded a stack of laundry and felt a lighter kind of tired.

Inside, our basil plant needed water. The dishes needed washing. The cat needed to be convinced that she was not, in fact, the queen of every pillow.

And me? I needed nothing but this: the knowledge that on Monday at 9:00 a.m., I would send money to no one but the future I was building. That the child who allegedly meant nothing to them takes up the whole sky of a small house that hums. That love is the only bill I pay on time without a reminder.

It turns out peace doesn’t have to be bought. It can be planted. Watered. Named. It grows even in small kitchens. It grows especially there.

Epilogue: The Gate

A year later, we moved to a place with a tiny yard and a gate that squeaks. On our first night, Ava stood by it and said, very seriously, “Mama, this gate keeps the wrong things out.”

“And the right things in,” I said.

She nodded like she had built it herself. She didn’t look for cars. She looked for the stars coming one by one like polite guests. We went inside, closed the door, and locked it. Not in fear. In ritual.

The gate squeaked once like a promise. The house hummed yes. And everything we let go of stayed gone, making room for everything we chose.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Karen Cut Down My Tree Without Permission — Until It Fell Right Onto the Sheriff’s Car!

When HOA Karen decided to cut down my beloved oak tree without permission, she thought she was being a hero…

I Hadn’t Even Taken Off My Jacket When My Dad Said, “Didn’t Realize They Let Dropouts In…

I Hadn’t Even Taken Off My Jacket When My Dad Said, “Didn’t Realize They Let Dropouts In Here.” A Few…

My Wife Did Everything To Exclude Me From Our Daughter’s Wedding—3 Weeks Later She Called About…

My Wife Posted Album: “Our Daughter’s Dream Wedding Yesterday!” 200 Photos. I Wasn’t Invited—Found Out From Instagram. I Commented Heart…

HOA Karen Tried to Kick My Guests Off the Lake—Froze When I Said “This Is My Private Land!”

I Got HOA Karen Tried to Kick My Guests Off the Lake—Froze When I Said “This Is My Private Land!”…

I Got Fired for “Having Two Jobs” — But HR Never Bothered to Find Out What Those Jobs Really Were

I Got Fired for “Having Two Jobs” — But HR Never Bothered to Find Out What Those Jobs Really Were…

Mom shouted, “Leave and don’t return!” So I did. Weeks later, Dad asked why I’d stopped paying

Mom shouted, “Leave and don’t return!” So I did. Weeks later, Dad asked why I’d stopped paying Part I:…

End of content

No more pages to load