I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” — So I…

Part One

I never thought a simple missed flight could change the course of my entire life. That Friday evening, Chicago O’Hare was its usual chaos—rolling suitcases, quick goodbyes, the impatient choreography of the endlessly late. I was one of them, breathless at the gate for the last flight to Indianapolis, the doors already sealed. Seventy is a milestone, and I had promised my mother I’d make the dinner. I stood there with my chest heaving and my boarding pass damp in my fist as the jet bridge retracted, taking my promise with it.

She was waiting for me by the vending machines—if waiting was what you’d call how she stood: still as a lighthouse, wrapped in a patterned shawl that didn’t belong to any airport. Her hair was silver, braided loose, her eyes a kind of sharp I felt rather than saw. I tried to pass. She stepped forward.

“You missed your flight,” she said, low and certain, as if she had closed the door herself. Before I could answer, she drew something from her shawl—a slender silver needle that caught the fluorescent light and threw it back cleanly. “Take this,” she whispered, pressing the cool metal toward me with both hands. “Check your husband and you’ll see the truth.”

There’s a part of you that laughs at omens in airports. Another part recognizes the gravity in a stranger’s face and the fear that’s been dozing in your chest for years. I should have walked away. Instead, I closed my fingers around the needle. It was heavier than it looked. When I glanced up again, she was gone, the crowd swallowed her, or she had never existed at all.

In the taxi back to the suburbs, the city lights smeared and then sharpened, as if the windshield were a lens being adjusted, and I kept replaying her voice: Check your husband. Fifteen years married to David Miller, from the outside picture-perfect—quiet neighborhood, two steady jobs, adequate vacations, dinners with friends—but if you’ve ever lived in a house with hairline cracks, you know when the light hits wrong. Late nights. Phone calls in another room. The way two people can touch knees on a couch and still be far away.

The house smelled like his cologne and good whiskey when I slipped in, shoes off to soften the sound of my entrance. Voices murmured from the living room—David’s in a register I associated with bad news, and another voice I didn’t know, deeper and colder. I stopped at the hallway opening, just where the wall broke into lamplight.

“You owe him,” the stranger said. “Silverman doesn’t care about your excuses. Twelve million, David. That was the deal.”

David’s reply came clipped, thin around the edges. “I just need more time. I can move money. Sell assets.”

“You don’t make promises to George Silverman you can’t keep,” the man said, and the threat in it moved through the house like a draft that knew the floor plan better than I did. “If you fail, you won’t be the only one paying the price.”

I pressed my hand over my mouth. I don’t know how long I stood there, breath shallow, heart a sudden, ridiculous drum. Long enough to realize I knew nothing about the man I lived beside. Long enough to know I couldn’t burst in without becoming part of something I didn’t understand. When the stranger left, his footsteps counted down the path like a metronome.

David moved through the next morning like the conversation had been an inconvenience. Coffee. Tie. Phone. Silence. When the shower started, I opened the closet. I don’t know why my hand went for one particular shirt—muscle memory of three a.m. laundry? The fortune teller’s needle was cold against my palm. I ran the point along a seam, a careful little surgery. The stitches surrendered with a whisper, and a plastic packet slid into my hand: small, crystalline pills, and a phone number in red ink folded tight.

“What are you doing with that?” David’s voice cracked the air behind me. Towel around his waist, water in his hair, eyes locked on the packet as if it were a snake in our bed. He snatched it, smiling a smile meant for boardrooms. “Supplements. Nootropics. Lots of guys at the office use them to stay sharp.”

“Hidden in your shirt,” I said. “Right.”

“Veronica,” he exhaled, exasperation staged to perfection. “You always do this. Take something small and—” He slid the packet into his briefcase. Kissed my cheek like an apology you send when you forgot to attach the file. “Don’t worry so much.”

I didn’t say a word. I listened to the door close and the sound of our life resetting itself to the wrong key. And then I paced. And then I stopped. The needle lay on the dresser like a dare.

The knock that evening was not neighborly. Four firm raps, measured as a heart monitor. The same man stood on our stoop, filling the threshold with the energy of a person who never waited. “End of the week,” he told David. “No more excuses.” He glanced at me briefly, the way a surveyor glances at property lines he intends to ignore.

Later, while the cul-de-sac twinkled benignly under porch lights and receding dinners, an SUV rolled up the drive. Four men climbed out and moved up the walk like the answer to a question we hadn’t asked. One of them spoke through the door and it opened because David opened it. They escorted him to the car. They did not look back. The taillights detached from our house and took my husband into the dark.

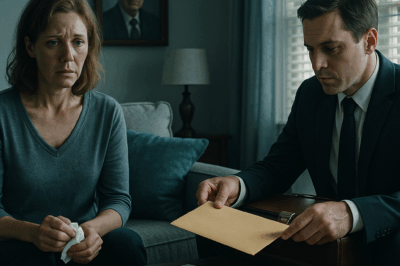

I called one person: Andy Summers. College friend turned prosecutor, one of those constants you don’t realize you’ve kept until you call them after midnight. I told him the fortune teller, the needle, Silverman, the pills, the men. He didn’t interrupt. When I was empty, he said, steady as a metronome, “Veronica, you need to be careful. Silverman is real. He doesn’t do second chances.”

An hour later, two unmarked cars idled under the streetlamp. Agents took pictures of the place where our life had looked normal. They looked at me like a witness, not a wife. One held up the packet I had found. “This isn’t caffeine,” he said. “It’s synthetic meth. High purity.” Andy stayed on my phone through it all. “Don’t throw the needle away,” he said. “It led you to one secret; it might lead you to more.”

It did. Not because it’s a magic wand, but because it made me look. Long after midnight, I saw the rug’s edge toed slightly off-square. I lifted the corner and found the smallest imperfection in the floorboard—a faint cut you’d miss if you weren’t hunting for fault lines. The plank came up with my nails and a grunt. Inside: a black USB drive and an envelope with my name in David’s handwriting.

Veronica, the letter read. If you’re reading this, I’ve run out of time. Plug in the drive. Whatever you do, give it to Andy. Trust him. Find the woman who gave you the needle—she’s not who she seems. I love you.

The video started with David’s face lit by a desk lamp, older and more tired than any version I knew. My name is David Miller, he said. For fifteen years I lived a double life. I was recruited by DEA to get inside George Silverman’s organization. I went in deep. Too deep. Then I met you and wanted out, but you don’t leave a man like Silverman. He suspects. You have to trust Andy. And the woman who gave you the needle—she’s undercover. Find her. She’ll help you. Veronica, I love you. That was never a lie.

The screen went black and left me with every version of my marriage at once: the Friday flowers and the late nights, the kisses and the secrets, the quiet mornings and the packet in his shirt. In the morning, Andy called. “We need to move you,” he said. “Silverman’s not going to knock twice.”

They took me downtown to an office that smelled like old coffee and institutional carpet. In a conference room with too-bright lights, a man introduced himself: “Name’s Stan Rushin. I was David’s handler. We’ll get him back. I just need that drive.” He was smooth, the kind of smooth that confuses you into thinking you’re safe. On his desk, half-covered by a file, a photo: David, handcuffed and kneeling in a concrete-green cell that didn’t cast shadows correctly. The background blur was lazy. My fingers were already on the edge of the print when the tiny earpiece the agents had given me crackled: Don’t trust him, Andy’s voice said. He’s the mole.

Stan saw the shift in my face. His smile evaporated. The gun appeared like a coin from behind a magician’s ear, pressed to my temple as if he’d practiced the movement on doors, on women, on fear. He dragged me half a step and the door blew open. “Drop it!” Agents filled the doorway, bodies filling angles they’d studied a hundred times. Stan didn’t drop it. He tightened his grip. Somewhere in me, a wire snapped clean. My hand found the needle because I had put it where my fear couldn’t reach it, and I drove that sliver of silver backward with everything I had. He gasped, loosened, and the agents surged. Shots, shouts, the sting of burned chemicals, glass giving up its cohesion. Then quiet. Then breath again.

I looked down at the needle—slick and proof. The fortune teller hadn’t given me magic. She’d handed me a way to insist on edges.

Back at the field office, the USB drive lay on the table between me and Andy like a loaded decision. “This is enough to take down half of Silverman’s network,” he said, voice tight with something like hope. “But David—” He stopped. He didn’t need to finish. The only thing I had now was the truth, and truths are not kind just because you need them to be.

I slept in a safehouse that didn’t feel safe and stared at the ceiling with the needle on the nightstand. The woman’s accent echoed through the air: Check your husband and you’ll see the truth. I had checked. The truth was complicated and bleeding. The truth had taken the shape of an old story: who a man loves, and who a man serves, and what a woman will do when she realizes she is the only person left to tell herself the truth.

Part Two

By dawn, a decision hardened in me that felt less like bravery and more like finally having run out of places to hide. The video, the packet, the needle, Stan bleeding under the weight of an arrest—every thread led back to the woman at O’Hare. If she was undercover, she wasn’t a ghost. Undercover agents clock in like the rest of us, just at different doors. And they come back to the places where people tell the truth badly and strangers miss flights.

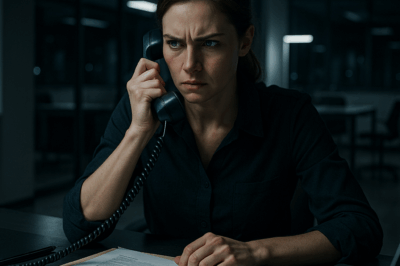

“I need to go to O’Hare,” I told Andy over bad coffee. “Alone.”

“You’re not going anywhere alone,” he said. “But we can arrange a controlled meet.”

In the end, we compromised: two agents within view, one trailing a handful of yards behind, an earpiece tucked warm against my skin. I took the Blue Line and walked into Terminal 3 with the purposed calm of a person who has learned to look normal while her life changes color. I stood by the same bank of vending machines where the needle had found me. The airport smelled like cinnamon and jet fuel, two scents that have always made people think they’re going somewhere special.

She appeared exactly where my intuition told me she would: behind me, so that when I turned it looked like I’d simply changed my mind about a snack. Same shawl. Same braid. Same eyes that could cut a lie down to size.

“You came,” she said, as if we’d booked this weeks ago.

“You vanished,” I answered. “And then men with guns came to my house and took my husband into a car that swallowed him.”

She nodded once, like a conductor acknowledging the players in the pit. “You brought it?”

I showed her the needle, held between finger and thumb, point down. She smiled—not kindly, not unkindly. “We don’t give people weapons,” she said. “We give them stories. Sometimes the stories are sharper.”

“Who are you?”

“Zoya Markova,” she said, an accent like a doorway into a colder country. “Cover enough to disappear, not so much I become a snowdrift. We have to talk quickly. Your friends think they’re the only ones who can do choreography.”

“Is David alive?” It came out too fast, too loud.

“Alive,” she said, and the word spread through my bones like heat for the first time in days. “Silverman keeps what he cannot yet sell. Your husband is leverage. He is also evidence. He is both at once, which makes him very valuable and very breakable.”

“You told me to check my husband,” I said. “I did and nearly burned down the rest of my life. Now what?”

“Now,” she said, “we get him back.”

She walked, and I followed, which is the thing we do when insiders finally show up. We headed for the end of the concourse and the chapel that airports maintain for those who need mercy near departure boards. In the small silent room with the stained glass airplane and the guestbook of names written in all caps, Zoya laid it out with the efficiency of someone who had spent twenty years being where she wasn’t supposed to be.

“Stan fed Silverman everything he needed,” she said. “Routes, names, where to find your house. He wanted the drive to clean up after himself. He failed, and that has made Silverman impatient. If we don’t move, David will become a lesson. He is in a warehouse on the Calumet River that used to ship tires and now ships other things. They change locations like shirts, but this one we can count on because laziness is the thing that takes down empires.”

“You keep talking about we,” I said. “What am I in this?”

“You are the reason he left,” she answered simply. “Which makes you the only bait he will take personally.”

“I am not bait,” I said, and my voice surprised even me. “I am a woman who used to make chicken on Tuesday nights and who has learned how to pry up floorboards and who does not appreciate being turned into a prop every time a man makes a mess.”

Zoya’s mouth quirked in what might have been her first real smile. “Good,” she said. “Then you will survive this. But if you want to be in the room when he breathes air without a bag over his head, you will have to stand somewhere dangerous for thirty seconds and not flinch.”

The plan was held together by the kind of string only professionals can tie: a controlled meet staged as a handoff, decoy drives, a perimeter built out of men and women who know how to spread out in shadows, radios bleeding back to a van that hummed like a heart. My part was infuriatingly simple—stand between two yellow lines in a place that had smelled like rubber and river long before any of us were born, hold the needle in my right hand where a camera could see it, hold nothing else in the left.

“Why the needle?” I asked.

“Because he told Silverman,” she said. “And Silverman told him to bring it to the man who introduced it. Men like tokens. They believe in talismans they can buy.”

We drove at dusk, a line of vehicles that looked like they had nothing to do with each other. The meeting spot squatted at the edge of the water, all corrugated metal and rust, the river wide and indifferent beside it. The sky turned bruise-colored. My breath fogged the air.

He came from the shadows the way he always had in my life these last few days—suddenly, and storytelling the air around him. David walked toward me with his hands out in that don’t-shoot posture that is half compliance, half theater. He was thinner. His eyes were the same. Behind him, men with guns and men with hands in pockets that meant guns. Zoya’s team bloomed outward from darkness, becoming real the way mountains do when fog lifts.

“Veronica,” he said, and there is a way your name sounds when a person hasn’t said it out loud for weeks and heard it in his head a hundred times. I wanted to touch him and I wanted to rage. I held the needle instead.

“You told me to find her,” I said. “I did. She says you told Silverman about the needle.” I wasn’t stalling. I was testing the edges.

“I told him enough that he needed to see it,” he said, and only later did I realize he looked past me twice—counting, cataloging, waiting for a cue. “You shouldn’t be here. But I’m glad you are.”

Zoya’s voice crackled in my ear: Now.

Everything that had been still moved. Floodlights knifed the dark. Commands slapped against the air, first in English, then shouted in languages that made no promises. The men behind David turned and reached and found themselves held at the edges by people who knew how to wedge a line into a circle. Someone fired against the roof to remind metal what sound grief would make if it had lungs. In the strobe of movement, David surged forward. A hand closed around my arm and another around the back of his shirt and for a split second we were both falling and then the van door slammed and Zoya said, “Drive.”

Bullets hit metal behind us. The river didn’t care. The city took the sound and angled it toward steel and stone until it became part of noise. Inside the van, David grabbed my face with his hands and for the first time since the video I saw his whole self—the brave piece, the selfish piece, the tired piece and the one that still believed in North. “I’m sorry,” he said, already crying and already apologizing for crying. “I didn’t know how to get out. I didn’t know how to come home.”

Zoya tossed a towel into his lap and a radio to a man whose eyes never stopped scanning. “You can be sorry later,” she said. “Right now you will listen.”

What followed took months to play out in courtrooms and conference rooms and back channels that smelled like paper and disappointment. The drive mapped routes and kickbacks and a system that had gotten so comfortable it forgot to lock its doors. Stan sang to save his life. People with clean fingernails who had never touched a gun found their names on documents they had failed to read. George Silverman was led down a hallway in cuffs and for a second looked like any other man who had believed he was smarter than the math that brought him there.

David’s status was more complicated than arrests or evidence. The bureau called him a confidential human source until the press called him an undercover agent and the internet called him a liar and my heart called him both. He testified with his hand raised and his voice steady. On cross, a man in a suit asked if he had slept at night. David swallowed and told the truth: no. Later, in the elevator, he told me he had written his confession to me a hundred different ways and thrown each version out because there’s no good way to say, I kept the worst part of myself away from you because I wanted the best part of you.

We had choices then, and none of them were the kind you can outsource to friends or therapists. Witness protection was offered the way hospital forms are offered with a pen attached. We could become people with new names who looked out at a new street under a new sky. Or we could stay and try to live in a world where people write your story for you in the comments.

“I will go where you go,” he said. “You don’t owe me a place in your life. But if there is a version of us that can breathe, I will build whatever that version needs.”

The hardest thing about choosing is that sometimes both paths are right and both are wrong. We sat in a quiet room with a window that looked out at a brick wall and decided to keep our names. We decided to stay. We decided that the way back was through the place we had been happiest—my mother’s little town outside Indianapolis, where people still put reservations under “Miller, party of two,” because they don’t need last names to get you to a table.

Six months after Silverman went down and the papers stopped using our photo as a synonym for complicated, we drove to that town. We were late for dinner—on purpose this time, because being early felt like a lie. My mother stood in the doorway with a dish towel over her shoulder, her hair greyer than the last time I’d seen her under chandelier light. “You missed the party,” she said, and then pulled me into her chest and cried into my shoulder.

David waited on the porch until she motioned him in with a nod that was not forgiveness and not condemnation. Just a mother doing the math of who hurt her child and who tried to put it back together. We ate too much and laughed at things that hurt and cried at things that didn’t and when the lights in the backyard clicked on and made the summer air whiter, my mother handed me a small box.

“Found this in your father’s old toolbox,” she said. “No idea what it is. Thought you might.”

Inside was a shadowbox I had made in third grade—pressed dandelion and a crooked crayoned house and a note that said, Things that are sharp can also be useful. I slid the silver needle into the box beside the flower and the house and the note.

We drove home under a sky that felt new because we decided it could be. The needle sits on our mantel now in that shadowbox, not because I believe in omens, but because I believe in reminders. It taught me to cut stitches that didn’t serve me, to sew seams I could trust, and—when the moment asked for it—to be sharper than the story others tried to write me into.

Sometimes the truth is that your husband was undercover. Sometimes the truth is that he lied. Sometimes the truth is both and you have to decide if both can live in the same house. We are building a house that can hold contradictions. It has a lock we both know the code to and a table we both set and a couch where two people can touch knees and still be close.

I missed my flight. A fortune teller handed me a silver needle. I checked my husband and saw the truth. The truth almost killed us. It also gave us back the only thing worth keeping: a life we choose with our eyes open.

In the airport chapel, a guestbook sits with more names than you’d think. Someone underlined a verse about needles and camels; someone else drew a tiny plane. If you flip to the back, you’ll find a line written in a hand you might recognize if you’d sat where I sat and heard what I heard: The needle finds the heart. Underneath, in my hand, a reply: And then we learn to stitch.

END!

News

My 89-year-old father-in-law lived with us for 20 years without contributing to our expenses. After his d.eath, I was sh0cked when a lawyer arrived with explosive news. ch2

I got married at 30, with nothing to my name. My wife’s family wasn’t well off either; there was only…

I Said Goodbye to My Dying Husband and Walked Out of the Hospital—Then I Heard the Nurses Talking. ch2

I Said Goodbye to My Dying Husband and Walked Out of the Hospital—Then I Heard the Nurses Talking Part One…

At His Estate, I Was Just the Caretaker — Until I Realized Who Set Me Up to Fail… ch2

At His Estate, I Was Just the Caretaker — Until I Realized Who Set Me Up to Fail… Part…

After My Husband Died, I Tried to Sell His Garage—But Inside Was Something I Never Expected. ch2

After My Husband Died, I Tried to Sell His Garage—But Inside Was Something I Never Expected Part One The…

My Husband Snarled Over the Phone, “You’ll Crawl Back on Your Knees!” — But He Never Expected… ch2

My Husband Snarled Over the Phone, “You’ll Crawl Back on Your Knees!” — But He Never Expected… Part One…

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House—But… ch2

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House—But… I grew up in…

End of content

No more pages to load