I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

Part 1

The scent of lilies and stale grief clung to me like a shroud. I stood in front of the cheapest pine coffin they could find and whispered, “I’m so sorry, Leo.” My voice cracked on his name.

Leo Welch. My husband. Gone at thirty-three. I was thirty-one, and it felt like we’d lived three lifetimes together and still hadn’t gotten to the part where things got easy.

The funeral director—professional in black, his brow fixed in that permanent tilt of sympathy—cleared his throat. “Mrs. Welch, we’re ready to finalize the arrangements.”

Every head in the small chapel turned to me. At the front, Leo’s mother, Mary, stiff in a gray suit, looked at me with the same expression she’d worn since the day we met: like I was a stain she couldn’t quite scrub out. Her eldest son, Logan—thirty-five, and the self-appointed guardian of the Welch “legacy”—stood beside her with his arms crossed and a smirk playing on his lips. His wife Olivia clutched her handbag like she expected me to try and steal it. Haley, the youngest at twenty-eight, didn’t look up from her phone.

“Payment, Mrs. Welch?” the director prompted again, his voice softer now.

I had twelve dollars in my pocket. Twelve. Hospital bills had eaten our savings. Leo’s paycheck had stopped the day his heart did. My own work had dried up in the weeks I spent in hospitals and waiting rooms. I hadn’t told anyone that I’d sold my laptop to keep the lights on for those last two weeks.

Before I could answer, Mary stepped forward, her voice slicing through the hushed air. “Honestly, Cameron, you should have married someone with more foresight. Someone who could afford to bury their husband properly.”

Logan chuckled. Haley glanced up, smirked faintly, then dropped her eyes back to the glowing screen in her hands.

The humiliation scorched hot up my neck. My own parents sat in the second row; my mother twisted her hands together, my father stared at the floor. Later, they would tell me it was time to “come home” and “start over” like I was a teenager who’d gotten in over her head at college, not a widow who’d just buried her husband.

I didn’t answer Mary. I didn’t answer the funeral director. I turned on my heel and walked out, my backpack heavy on my shoulders, the weight of those twelve dollars heavier still.

My Honda Civic was waiting in the lot, paint faded, the engine coughy from years of Leo’s patient maintenance. I started it, not looking back at the chapel, and drove until the city lights shrank to a glow in the rearview mirror.

That night I parked behind an Exxon station. The smell of fuel and burnt coffee drifted through the cracked window as I lay back in the seat. Twelve dollars. That was it. I could stretch it for maybe two days if I rationed coffee and gas station ramen.

I swore, in that thin slice of pre-dawn, that I would never need any of them again. Not his family. Not mine.

The twelve dollars ran out in forty-eight hours. After that, the Civic became my everything—bedroom, office, kitchen. I rotated parking spots: Walmart lots, quiet side streets, the back edges of industrial parks. Always with one eye open.

Days, I camped at the public library. Free Wi-Fi. Bathrooms with warm water. A corner table where no one looked too closely at how long I stayed. At first I just… scrolled. Anything to drown out the grief and the shame. One afternoon I clicked on a YouTube video of some kid disassembling a phone—logic board laid bare, tiny screws lined up like soldiers. The precision mesmerized me.

Leo used to joke that I had X-ray vision for electronics; I’d fixed his old laptop with nothing but a borrowed screwdriver and a blog tutorial. Watching those videos, something clicked. My hands knew how to do this.

I started collecting broken devices from dumpsters and curbs: shattered-screen phones, dead tablets, old laptops. I bought a cheap toolkit with my last few dollars. The backseat of the Civic turned into a miniature repair bench. At night, under a headlamp, I practiced: prying open cases, swapping out charging ports, teasing tiny ribbon cables free without tearing them.

Two months in, I could diagnose a dead motherboard just by looking at it. I joined obscure repair forums, posting under “Cameron R,” helping strangers troubleshoot just for the challenge.

That’s when the message came—from a user called “BiteKing.”

Saw your posts on the deadboard revival thread. Got a job for you if you want it. High risk, high reward. Cash.

The photos he sent looked hopeless: a motherboard waterlogged and charred, the kind of job most shops wouldn’t touch. He called it “critical data recovery.” I called it a chance.

Three days in the Civic, hands cramped, back screaming, fueled by gas station coffee—and the data flickered to life. BiteKing, real name Brian Carter, paid me more than I’d seen in months. Enough for better tools, a P.O. box, and a warm meal that wasn’t shrink-wrapped.

“You’re good, Cameron,” Brian said over an encrypted call. “Ever thought about going pro? Anonymously?”

That’s how Vexa was born.

Vexa had no face, no real name—just a reputation in the dark corners of the internet for fixing the unfixable, recovering the unrecoverable, bypassing whatever others called impossible. Jobs came through encrypted channels, payments in untraceable transfers. The work was high risk, but the reward… I was finally building something.

One night, a new request pinged through: Project Red Tears. Corrupted surveillance system. Colonial estate. Cash buyer wanted the system audited and vulnerabilities exposed.

The address in the specs made my hands still on the keyboard. The Welch family home.

I dug. Property records showed “urgent sale—cash buyers preferred.” Deeper still, and the picture emerged: Logan had sunk the family trust into a disastrous crypto play. The house was collateral. They were desperate.

Two years after leaving that funeral with twelve dollars, I wasn’t just surviving. I had the skills. I had the money. And now, I had the perfect opportunity.

Part 2

I didn’t sleep the night after I handed Mary the motel key. I lay on the floor of the empty study—the only room that didn’t echo my footsteps—and watched moonlight crawl the wall where her wedding portrait used to hang. It wasn’t triumph that kept me awake. It was the drum of everything that came next.

Justice is never a single event. It’s a ledger you audit, number by number, until the balance is true.

By morning, the headlines had multiplied. Welch Industries CFO Under Investigation as Widow Questions Circumstances of Husband’s Death. Olivia’s influencer friends pivoted from deifying her pool parties to dissecting her “cruelty”—a word that looked strange beside someone who cried at perfume commercials. Haley’s text pinged at 6:12 a.m.

I’m sorry. I can help you clean it up. I don’t want to be them anymore.

I stared at the words until the phone dimmed. Then I went downstairs and made coffee on a camp stove because the gas service still sat in some limbo of legal paperwork. I drank it on the back steps where Leo and I used to sneak away during holiday dinners to breathe.

He’d sit on the top step, elbows on his knees, and narrate the night like a sports commentator.

“And in the southeast dining room,” he’d murmur, “the eldest Welch male makes a risky attempt to monologue about interest rates while his wife’s face indicates she would rather eat the china.”

Back then I thought the laughing made it survivable. Now I knew it only turned down the volume.

I texted Haley one line: Come at noon. No phones.

She arrived five minutes early in a hoodie and sunglasses, hair knotted on top of her head like she’d yanked it up with both hands. Up close, the veneer cracked: bitten cuticles, a constellation of stress acne along one cheek, a bruise-yellow crescent at her temple she tried to hide with concealer and failed.

“Fell into a cabinet,” she said when my eyes found it.

“Logan?” I asked.

Her face tightened, and she didn’t answer.

We sat in folding chairs in the empty parlor like two kids in trouble. I set a recorder on the mantelshelf, its red eye blinking. “I’m not interested in ruining you, Haley,” I said. “But I need the truth in the record.”

She took a breath like someone about to swim the length of a pool underwater. “I thought the money made us safe,” she said. “I thought… if I just didn’t look at the ugly parts, they couldn’t touch me.” Her mouth twisted. “Logan said Leo was weak. That he took the wrong shift, that he didn’t follow protocol. He said… it was sad, but these things happen. When I saw the policy date, I knew. I knew it wasn’t an accident to them. It was arithmetic.”

The recorder kept blinking. Outside, wind scraped the boxwoods against the windowsill.

“Mary called it ‘a provision,’” Haley continued. “Said real grown-ups prepare for worst-case scenarios. The night of the accident, she told the ER doctor we wanted ‘comfort measures only.’ She said Leo wouldn’t want machines. She didn’t ask you because you’d ‘fall apart and embarrass everyone.’ When you got there, she kept you in that glass room and told the nurses not to let you back. I—”

Haley’s voice broke. She pressed a fist to her mouth and inhaled hard through her nose. When she spoke again, it was smaller. “I tried to text you. Logan took my phone.”

He would have. He was always better at catching things than throwing them.

I reached up and clicked the recorder off. “Why tell me now?”

“Because you didn’t just burn their house down,” she said. “You lit up the whole street so I could see. I’ve been living in a room with no windows.” She swallowed. “I don’t know how to live somewhere else. But I want to.”

I believed her. Maybe because there was no performance left in her. Maybe because I could see the kid she used to be—awkward and too tall, hiding behind an older brother who’d weaponized her invisibility.

“You’ll write a statement?” I asked.

She nodded. “I’ll sit for whatever you need. I’ll testify. I’ll… I’ll pay back what I can. I don’t have much, but—”

“I don’t want your money,” I said. “I want your memory. The parts nobody recorded.”

She flinched at that and then nodded again like a soldier.

When she left, she hugged me. It wasn’t pretty. It was a clumsy collision of elbows and apology. But it was the first thing anyone in that bloodline had given me that didn’t come wrapped in contempt.

Brian sent me a message with a link to a shared drive and a single sentence: You ready to go loud?

“Loud” in Brian-speak didn’t mean press conferences or weepy videos addressing “the community.” It meant something precise: documented, timestamped, corroborated. It meant we weren’t asking anyone to believe us; we were asking them to read.

We published a dossier. Not to tabloids, not to Jolie’s parasitic audience, not even to my personal accounts. We filed it as a complaint with the Department of Labor and OSHA: negligence, financial coercion, ethical breaches in medical decision-making. We attached affidavits from Haley and two anonymous plant workers who’d been waiting for somebody—anybody—to go first. We included copies of the budget cuts, the policy date, the email from Mary with provision in the subject line, the redacted medical report with its redaction undone.

And then, because some truths need to breathe outside meeting rooms, we mirrored the dossier on a public site—a simple page with a single header: LEO.

No last name. No dramatics. Just the person they tried to erase.

By sundown it had a hundred thousand views. By noon the next day, five hundred thousand. Reporters called. Lawyers called. A woman I didn’t know in a town I’d never visited sent a voice note that began, “My husband died on a shift he shouldn’t have been on. When I asked why, they told me the schedule was fixed.”

I didn’t reply to any of them that first day. I sat on the back steps again and watched two girls from our new training cohort kick a soccer ball across the lawn where the caterers used to set the rented tent. One girl had her hair in blue braids. The other wore a neon hoodie and boots scuffed white at the toe.

They laughed the way teenagers do, hard and free, like sound itself was a resource you couldn’t ever exhaust.

When the ball hit a yew and ricocheted toward the porch, the girl in the hoodie chased it and skidded to a stop when she saw me. “Sorry!” she said, half-gasping.

I picked up the ball and spun it on my palm. “Tell your coach to move the cones a foot to the left,” I said. “Wind’s pushing your shots.”

She squinted at me. “You’re not the coach.”

“More of a groundskeeper,” I said. “But I pay attention.”

Her grin flashed like a match. “I’m Ky,” she said, and held out a hand. “The blue braids is Jules. We’re on the PCB repair track. Jules says she’s going to be better than you in a month.”

“Jules should aim higher,” I said, tossing the ball back. “I’m only good because I was hungry.”

They took off, already laughing again, the ball banging off one of the stone lions flanking the terrace. The lion blinked in the sun like a creature just waking up.

Mary filed a defamation suit. Of course she did. It had two causes of action: reputational harm and intentional infliction of emotional distress. Brian sent me a PDF at 2 a.m. with a subject line that only read: lol.

He told me not to worry. I didn’t, exactly. But in the hours before dawn, I sometimes imagined the old Mary, the one from when Leo was a kid—the one who took him to the museum on Tuesdays because admission was free. Had she ever existed? Or had grief erased her before grief even arrived?

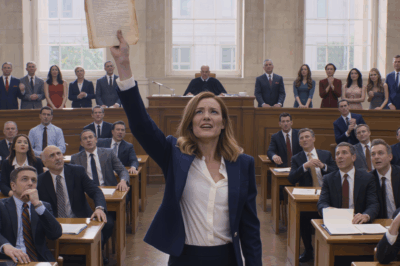

When the suit made the docket, it also made the morning shows. Which meant the morning I walked into a courtroom again, I did it in front of cameras. My palms didn’t sweat. My heart didn’t sprint. I’d already done the hardest thing anyone ever asked me to do: leave with twelve dollars and not come back.

Mary wore gray again and a new set of pearls—as if pearls could make a different argument than the one her face made. Logan wasn’t with her. He was working the only strategy left to him: hide and hope the fire burns out.

The judge was a woman in her fifties who had the patient fury of a person who’d read too many pages of preventable damage. She let Mary’s lawyer talk for twelve minutes uninterrupted, then held up a hand. “Counsel,” she said, “your client’s problem is not defamation. It is documentation.”

Brian leaned over and scribbled something on his legal pad. It was a tiny pizza with a speech bubble that said, Objection: cheesy. I snorted, too loud for court. The judge cut me a look that was not unkind.

“You want to keep going?” Brian whispered.

“We are going,” I said. “With or without a gavel.”

The suit died where it stood. I walked out into sun sharpened by winter air and a sidewalk full of microphones and didn’t say anything into any of them. A younger me would have. She would have wanted the last word, the ten-second clip that played well in strangers’ living rooms.

I’d learned something in the months since I became Vexa, and then stopped needing to be. Silence is not absence. Sometimes it is a structure you build so the truth has somewhere to sit.

I went to see Mary at the motel the night before the sheriff’s sale of the condo I’d bought, then sold, then re-purposed, then let go of entirely. I brought her a bag of groceries and a flyer.

She answered the door with her mouth already open like a pitcher.

“You’re not welcome,” she began.

“It’s not your house,” I said. “You don’t get to decide who’s welcome in rooms you don’t pay for.”

She tried to slam the door. I stopped it with my palm and the quiet force of someone who’d learned to carry weight without showing it.

“Mary,” I said, and the name came out of me with no malice in it, which shocked us both. “I brought eggs and soup and bread. I brought a flyer for a grief group that meets two blocks over on Tuesdays because that’s still your day for free things.”

Her eyes flickered. The muscles in her jaw flexed. “You’re enjoying this,” she said.

“I didn’t enjoy any of it,” I said. “Not one minute.” I held the flyer out. She didn’t take it, so I set it on the nightstand inside the door. “There’s a number on the back for an advocate at the hospital,” I said. “You’re going to get asked questions you won’t want to answer. Call her before you answer them. You’re going to need an attorney who doesn’t lie to you. I wrote down names.”

Mary’s mouth clicked shut. She looked at the bag of groceries like it was a trick.

“You think this makes you better than me,” she said finally.

“No,” I said. “I think it makes me done.”

I stepped back into the hall. “You can hate me,” I said. “I won’t give it back.” And then I walked away.

In the parking lot I sat in the driver’s seat a long time without turning the key. The motel neon bled red on the glass. I remembered Mary standing at the foot of the hospice bed with her hands folded like a schoolgirl praying to the wrong God. I remembered Leo’s breath rattling. I remembered the way the nurse cut off the oxygen alarm with her thumb and how small the room felt when a machine stopped arguing with the air.

No, I didn’t enjoy any of it. But joy isn’t the only measure of whether something matters.

The LEO site became more than a complaint. In three months, we had fifty-seven reports from workers in three states. Brian built the database because he liked to pretend he didn’t care and then do the kindest thing you could imagine without telling anyone. Haley ran intake. She was good at listening without filling the quiet. She learned to say, “I hear you,” instead of “I’m sorry” because some things deserve mirrors more than bandages.

Ky and Jules got their first contracts repairing logic boards for a refurbisher who paid on time and in cash. The day Ky brought me a check with her name on it and zeros she’d earned, she cried in the kitchen, and then laughed, and then cried because she’d laughed while she was crying like it meant something was wrong.

“It means everything is working,” I said. “All systems normal.”

We hosted our first class in the dining room with the table leaves removed and anti-static mats lined up like a runway. Twelve women, ages nineteen to forty-three, learned to wick and reflow and test for shorts. Someone burned a finger. Someone soldered to the wrong pad. Someone who’d never been told she could be good at anything lifted a microscope, found a hairline crack, and whispered, “I see it,” like a prayer.

I hung two photographs in the foyer where the oil portraits had glowered for decades: one of the girls playing soccer, all elbows and knees and laughter; one of Leo in a thrift-store suit on our wedding day, crooked tie, crooked grin, holding a bouquet he’d made himself from grocery store tulips and a sprig of rosemary because it “smelled like brave.”

On the anniversary of his death, I took the second photo down and brought it to the graveyard. I sat on the grass, not caring that the ground was cold or that my coat wasn’t warm enough.

“They read it, baby,” I said to the stone. “They finally read it.”

Wind moved through the oak above me with a sound like distant surf. A crow landed on the far corner of the fence and swore at me for invading its afternoon. I reached into my pocket for the thin brass key I kept there—a relic from the condo, not because I needed souvenirs but because I needed reminders. I set it on the dirt and pressed it down until the earth took it.

“I don’t need doors,” I said. “I build openings.”

I stayed until my fingers went numb and then I went home.

Six months after we published, Welch Industries declared bankruptcy. The plant was bought by a cooperative, half the board made up of workers who’d punched in there for twenty years and knew which motors sang and which ones were about to burn. They rehired more than anyone thought they would.

Logan took a plea deal on the financial crimes. He won’t go to prison forever, because this isn’t a movie, but he will be poor, and he will be ordinary, and that may be a worse sentence for someone who thought money made the mirror tell the truth.

Mary’s defamation suit vanished into that long night where bad ideas go. She moved into a one-bedroom apartment on the bus line and, according to a whisper routed through a cousin who still speaks to everybody, she goes to the Tuesday group sometimes. I don’t need to know whether she talks. It’s enough that she sits in a circle where someone could look at her and say, I hear you.

Haley started taking classes at the community college. She texts me pictures of her notebooks: margins filled with doodles of circuits and little cartoon lungs with sparkles around them because she says breathing is a hobby now. Sometimes she comes over and helps Ky and Jules with their homework, and they roll their eyes because “ugh, Haley,” and then ask if she wants to order dumplings and not tell me how many.

I still fix things, but not for ghosts. Vexa exists the way a retired knife exists: sharp if you touch it wrong, not interested in shining. Sometimes I take a job because a stranger says “please” like a person drowning, and sometimes I send it to one of the girls because their hands are steadier than mine now and that makes me proud in a place so deep I don’t have a name for it.

I got a letter from Leo’s great-aunt’s lawyer—the one whose estate Logan had tried to disappear. It was handwritten and smelled like violet talc when I opened it, a ghost of the woman who’d saved catalog clippings and cash in freezer bags. I always hoped the right person would find this, the letter said. I don’t know who you are, but if you found it, you’re the right one. Make something better than a trust fund.

I taped it inside the supply closet door where the girls keep the isopropyl and the Kapton tape and the box of band-aids for when someone forgets that heat is not an idea. Every once in a while someone reads it and says, “She sounds like my grandma,” and I say, “She sounds like everybody who ever put five dollars in a coffee can and said ‘someday.’”

On a warm night the following spring, I hosted a dinner. Not a gala, not a fundraiser, not a press event. A dinner with folding tables and mismatched plates and food that steamed in the cool air. We ate outside under strings of cheap bulbs because the expense of a chandelier is a tax on people who don’t know how good the sky looks.

Brian came and pretended to be uncomfortable around so much sincerity and then laughed at one of Ky’s terrible jokes until he had to put a hand on the table to breathe. Jules’ mother brought arroz con pollo and three types of pickled onions. Haley made a cake that collapsed in the middle and then declared it a crater and filled it with berries like a tiny universe.

After we ate, we played music from someone’s phone and danced on the flagstones with the caution of people holding full cups and full hearts. I am not a good dancer. I move like someone trying to get a very determined cat off a countertop. It didn’t matter.

At some point I walked away from the noise and stood on the back steps again. The lawn rolled down to the trees, the trees held up a slice of moon, and for a second the house didn’t look like a house. It looked like a possibility that had gotten tired of waiting to be used.

I felt a presence beside me—not the kind you have to pretend about, not the kind you conjure because it hurts less than the alternative. Just the simple awareness of space making room for memory.

“I did it,” I said.

The wind moved across the grass.

“And I didn’t do it like they would have,” I added, because that mattered to me. “I didn’t become them on my way to outliving them.”

Behind me, laughter spiked, then fell into a hum. Someone must have spilled something, because a chorus of “oh no” rose and then turned into “it’s fine” like a blessing.

I turned back toward the noise—the clatter and the voices and the light—and realized I was no longer measuring my life by what I’d lost, or what I’d taken back. I was measuring it by what I was building.

For months, I’d been thinking in closures: cases closed, accounts closed, doors closed. But that night the word that came to me was simpler and bigger.

Open.

Open like a ledger finally balanced. Open like a window after a long winter. Open like a door you hold for someone behind you because someone held it for you once, when you had twelve dollars and more debt than hope.

At the very end of the night, after the dishes were stacked and the last car’s taillights were a smear on the road, I walked into the foyer and looked up at the place where Mary’s portrait had glared down on generations of Welches who learned how to perform before they learned how to tell the truth.

I hung a new frame there—a printout of the LEO header page, corners held by brass tacks because ornate frames are cages. Under it, I taped a quote Ky liked to write on her notebooks: The digital bones always tell a story. You just have to know how to listen.

I locked the door and went upstairs to the small room I kept at the back of the house. The window looked west. I brushed my teeth with the bathroom light off because the moon was bright enough. I lay down and fell asleep fast, without dreaming, which felt like a luxury so grand no one had invented a price for it yet.

In the morning, the house woke before I did. Somewhere downstairs a microwave door clacked; a kettle hissed; a girl with blue braids scolded a girl in a neon hoodie for using the good tweezers to open a bag of chips. I smiled into the pillow.

I’d left with twelve dollars. I’d come back with less than that and more. The house didn’t matter anymore because a house is just a container. What mattered was what we’d poured into it: tools and time and tenderness and truth, the four currencies nobody can repossess.

On my way to the kitchen, I passed the front hall and saw a woman on the porch, mid-fifties, posture like a question. She wore a coat too thin for the morning and her hands were empty.

When I opened the door, she startled, then steadied.

“Is this the… the training place?” she asked.

“It is,” I said.

“I saw the thing online,” she said. “The… the Leo site. I don’t know if I’m too old for this kind of work.”

“You’re not,” I said.

She nodded, eyes wet but not weeping. “I’m tired,” she said. “But I’m not done.”

“Good,” I said, stepping back, holding the door. “Neither are we.”

She came in past me, shoulders squared a fraction. I closed the door against the cool, and inside we set water to boil, and turned on the lights over the mats, and made room at the table.

Justice had been served in full. Mercy—unexpected, undeserved, unasked for—found whatever space was left and sat down with us, picked up a screwdriver, and got to work.

I had left with twelve dollars. Two years later, I bought their house in cash. And in the years after that, we bought a better future together, one steady hand-soldered joint at a time.

Part 3

Year three in the house, the floorboards finally stopped sounding like they were asking me who I thought I was.

At first, every step felt like trespassing. The grand staircase, the heavy banister Leo used to slide down as a kid when Mary wasn’t looking, the hall runner that had seen more designer shoes than work boots—they all seemed to whisper, Not yours. You can buy the deed, but you can’t buy belonging.

Belonging isn’t bought, though. It’s repeated.

Bootprints in the kitchen at six a.m. because Jules forgot her badge and texted, Panicking, plz rescue. The squeak of sneakers in the hallway as Ky and two newer trainees raced to see who could bring a dead laptop back first. Haley’s laugh bouncing off the high ceiling during lunch, her voice calling, “Who stole my Tupperware again?” as if the question didn’t answer itself.

Three years in, the house no longer looked like their house.

The portraits in the hall were gone, replaced by framed schematics and simple black-and-white photos of hands working—soldering, typing, writing, holding. The bar cart that used to groan under expensive bottles now held spools of wire, magnifying visors, and a jar of Sharpies with the word LABEL written on it three times. The piano in the parlor, which no one in the Welches had touched in a decade, had become the staging ground for packed lunches on workshop days.

I still kept one thing of theirs in its original place: Leo’s father’s toolbox, dented and scratched, on the shelf in the garage. It had been his inheritance, the only thing he claimed from this house. The rest hadn’t felt safe to take.

“I wonder if he’d hate this, or love it,” I said one afternoon, wiping sweat off my forehead with the back of my wrist.

Brian, half under a table tracing Ethernet cables like he was following a rumor, grunted. “Love what?”

“That his family’s museum turned into a community college,” I said.

Brian slid out and squinted up at me. “He used to tell me in the break room,” he said, “that if he ever accidentally got rich, he’d open a weird little school that taught kids to actually fix things instead of throwing them away. Didn’t think he meant this house, but…”

He gestured around. We stood in what used to be the formal dining room. The long mahogany table was gone—sold to pay for the first run of oscilloscopes—and twelve sturdy workbenches stood in its place. Anti-static mats. Lamps. Labeled bins of components. One whole wall painted with whiteboard paint covered in notes, ideas, equations written by hands that didn’t always trust themselves until they left proof in marker.

“He’d like it,” Brian said. “He’d make fun of you for naming the soldering irons, though.”

“They’re temperamental,” I said. “They deserve names.”

He smirked and ducked back under the table.

We ran cohorts now. Twelve-week training programs, three times a year, for people who’d never been told the inside of a device was somewhere they were allowed to go. Some were out of work; some were under the table; some had never had a job that asked anything of them but stamina and silence.

We didn’t promise miracles. We promised skills. Knowledge. A path that wasn’t just “pick up whatever shifts they give you until your body gives out.” In the first three years, forty-seven people had gone through our program. Thirty-nine were employed in repair, refurbishing, or adjacent fields. Four had started micro-businesses of their own. Two had moved away and still sent emails once a month: pics of their new benches, their first client reviews, their kids holding up a soldered joint like a trophy.

“Found another one,” Ky said, dropping onto the bench next to me with a thud. She pushed a cracked phone across the mat. “Kid tried to fix their own screen. Glued the new one on without disconnecting the battery.”

“Fireworks?” I asked.

“Mini show,” she said. “But the board’s salvageable if we clean it. Want to make this a demo? Show the newbies not to fear other people’s messes?”

“Always,” I said.

She grinned and went to round them up.

They still called me “Cam” or sometimes “Boss” when they wanted to annoy me. Never Mrs. Welch. That name had been taken from me at Leo’s funeral like a coat that didn’t fit the room. I didn’t want it back. I’d learned to hear myself without it.

The LEO site had grown beyond anything I could have predicted.

At first it was just a complaint portal turned public archive—a ledger of near misses and not-misses, of men and women whose stories read like echoes of Leo’s. Then a non-profit in another state reached out. Then a union organizer. Then a lawyer specializing in workplace safety.

“We’ve been putting these cases together one by one,” she said over video. “You’ve just handed us pattern.”

We partnered. We built tools: anonymized reporting forms that channeled straight to investigators; templates for workers to document conditions; plain-language guides to rights they’d been told they didn’t have. We ran webinars from the house, the dining-room-turned-lab behind me as backdrop. I never underestimated the power of visual metaphor: the widow who’d bought the house turned it into a school and a shield.

Leo’s name became a shorthand in some circles—not for tragedy, but for the moment something stops being an individual mistake and becomes a system you can point at.

“Do you ever… regret going public?” Haley asked one evening, when we sat on the back steps sharing a bag of chips that had probably expired two months ago.

She’d grown into her face in the last few years. The bruises were gone. The hunched posture too. She wore her hair shorter now, in a chop she’d given herself in my downstairs bathroom one night when she realized she didn’t need to look “presentable” for Logan anymore.

“Sometimes,” I said honestly. “When I think about how tired I am. When I get letters from people who are still in it and know we can’t pull them out fast enough. When I imagine what Leo would have said.”

She nudged me with her shoulder. “He’d say you were being dramatic,” she said. “Then he’d bring you diner coffee and tell you to keep going.”

“Probably,” I said.

She crumpled the chip bag and launched it toward the recycling bin at the base of the steps. It went in. “Two points,” she said.

“You know he’d be proud of you too, right?” I added.

She stiffened slightly. “I stayed quiet too long.”

“You spoke when it mattered,” I said. “That’s not nothing.”

She stared across the yard. “I still dream about the glass room,” she admitted. “You know. In the ICU. I see you standing on one side and him on the other and Mom between you, and I’m… nowhere. I’m not even in the dream.”

I knew that room. I’d seen it in my own sleep. “You’re in it now,” I said. “You walked into the memory and changed it. That counts.”

She exhaled, the sound thin and shaky, then laughed once. “You always talk like that?”

“Like what?”

“Like you’re narrating a documentary,” she said.

“Occupational hazard,” I said. “Exposure to lawyers and grief.”

She leaned her head against my shoulder for a second. It was brief and clumsy. I cataloged it as progress in a ledger no one else could see.

A year later, the factory co-op invited me to speak at their general assembly.

The plant floor looked different. Cleaner. New signs, hand-painted by someone who cared, hung above stations: KNOW YOUR RIGHTS; KNOW YOUR WORTH; KNOW YOUR EXIT ROUTES. The machines were the same, the hum familiar. But the faces around the tables looked… brighter. Not happy all the time; that would have been a fantasy. But awake.

“We’re voting on our first surplus allocation,” the co-op president said, a woman named Trina who had calloused hands and a voice that could command a room without a mic. “Ten percent to maintenance reserve, five percent to training, ten percent to a hardship fund.”

“And?” someone called from the back.

“And ten percent to LEO,” Trina said. “For scholarships and emergency support for workers in other places who haven’t won yet.”

They clapped. One guy whistled. I felt my face heat.

“I didn’t come here to ask for money,” I said when they handed me the mic.

“Then you came unprepared,” Trina said, and the room laughed.

I looked around and saw people Leo had known. Men he’d smoked with under the loading dock roof on rainy days. Women he’d covered shifts for when they had child-care emergencies. A twenty-year-old forklift driver he’d trained, now with a little girl perched on his shoulders wearing noise-canceling headphones too big for her head.

“I came to say thank you,” I corrected. “Because you proved something I’ve been shouting into the internet like a crazy person trying to be heard over car horns.”

“Which is?” someone asked.

“That the people who do the work should have the power,” I said simply. “And that when they do, fewer people die. Fewer people get hurt. Fewer spouses go home alone.”

Silence settled gentle, like a blanket, not heavy enough to smother, just enough to warm.

On my way out, Trina pulled me aside.

“You know Logan’s up for parole next year,” she said.

I hadn’t thought about his timeline in months. “I do now,” I said.

“He ain’t coming back here,” she said. “We voted on it. He tried to call me last month. Wanted to ‘consult.’” Her lips twisted. “I told him we don’t pay for ghosts.”

“Good policy,” I said.

“You going to go to his hearing?” she asked.

The thought made my stomach flutter, not from fear but from something like… curiosity.

“I haven’t decided,” I said.

“Whatever you decide,” she said, “don’t do it for him. Do it for you. If you need to say something, say it. If you’re done, stay home and build something. Both are holy.”

I nodded. “Is that in your bylaws?” I asked.

“Article thirteen,” she said. “Section two: Thou shalt not waste time on men who ain’t sorry.”

We laughed, and then I drove home.

Part 4

The day of Logan’s parole hearing, I woke up before my alarm and sat at the edge of the bed, fingers twisted in the hem of the blanket.

I’d told myself I wouldn’t go. For months, when the letter from the Department of Corrections sat propped on my desk like an invitation from a universe I wasn’t sure I believed in, I’d told myself I was done. Trina was right: I didn’t owe him anything. Not presence, not words, not witness.

But obligation and completion aren’t the same thing.

“Go,” Brian had said, dropping a box of donuts on my desk the day before. “Or don’t. But decide, and then own it. Don’t half-commit out of spite. That’s their religion, not yours.”

In the end, it wasn’t Logan that made up my mind. It was Leo.

He’d always said closure is a myth people invented to sell self-help books, but he’d also believed in not leaving doors half-open.

“Drafts waste energy,” he’d say, stuffing an old towel under the base of the back door in winter. “Either open it and go through or shut it and stay.”

So I went.

The prison was an hour away, a low-slung complex of beige and barbed wire on the edge of nowhere. The waiting room smelled like nervous sweat and vending machine coffee. Other people sat with their own folders, their own ghosts. A woman in a navy dress clutched a photo of a young man in a cap and gown; a guy in a stained jacket stared at his shoes.

A guard called my name. “Welch,” he said, mispronouncing it only slightly differently than the judge had at the bankruptcy hearing.

The room where the hearing took place was small and bright and cold. Two plastic chairs on one side of a table for the board members, one on the other for Logan. I took a seat against the back wall with the other observers.

Logan shuffled in in beige. He’d lost the weight that came with boardroom meals and no heavy lifting. The angles of his face were harsher. His hair, buzzed, showed the first real grays I’d seen on him. He didn’t see me at first. Or he did and pretended he didn’t. Performance was still muscle memory.

The board asked their questions. The script was familiar: remorse, rehabilitation, plans for re-entry. Logan hit his marks.

“I’ve had a lot of time to reflect,” he said. “I realize now I prioritized profit over people. I lost sight of what mattered. My brother’s death… that was a wake-up call.”

The word my in front of brother made something twist in me.

He went on. “I want to make amends.”

“How?” one board member asked. “Be specific.”

He hesitated. “I’d like to… volunteer. Help others avoid my mistakes. Speak to business schools about ethics.”

I almost laughed.

“Anyone here wish to make a statement?” the chair asked.

I hadn’t planned to. My heart climbed into my throat anyway.

I stood.

Logan’s eyes snapped to me, and for the first time in a decade, I saw something that wasn’t arrogance or stress. I saw fear.

“Ms…?” the chair prompted.

“Cameron,” I said. “Leo Welch’s widow.”

A flicker at the table. The name still held weight in certain files.

“I’m not here to argue for or against his parole,” I said. “I’m here to correct the record.”

Logan’s jaw tightened.

“Leo’s death wasn’t his ‘wake-up call,’” I said. “It was his ledger closing. He never got a chance to make amends or reflect or go on speaking tours. He went to work, like he always did, and didn’t come home.”

I kept my voice steady, because anger would have been easy and easy never carried the point with people like this.

“Logan talks about prioritizing profit over people like it was a slip-up,” I continued. “It wasn’t. It was policy. It was pattern. It was emails and memos and schedules and budget cuts that told men like Leo their lives were variable costs.”

I looked at him then. Really looked. His shoulders were hunched, his eyes dark.

“Since he’s been inside, workers have organized,” I said. “They’ve formed co-ops, read their contracts, refused unsafe shifts. Logan’s company went bankrupt, and other people made something better out of the wreckage. They did that without him.”

I turned back to the board.

“Whatever you decide today,” I said, “don’t confuse his newfound vocabulary with leadership. He can do his amends in a soup kitchen or a halfway house or in an apology letter he never sends—not as the face of a redemption story. Don’t give him another stage to stand on while the people in the wings are still sweeping up.”

I stepped back. My knees shook. I sat down.

The board thanked me. They adjourned. They told Logan they’d mail their decision.

As we filed out, he caught my eye.

“Cam,” he said. His voice was small. I’d never heard it small.

I could have walked past him. I could have pretended I hadn’t heard.

“You remember Leo’s voice when he’d do sports commentary over dinner?” I asked instead.

It wasn’t what he expected. His brow furrowed. “What?”

“I hear yours like that now,” I said. “Background noise over a game you’re not playing in anymore.”

His mouth opened. “I did love him,” he said. “In my way.”

“In your way, he was a line item,” I replied. “In mine, he was the whole budget.”

I left without looking back.

Outside, the sky was bright and indifferent. In the parking lot, a man in a faded work shirt was helping his daughter into a car seat. She fought him with a ferocity that said she’d have opinions about everything forever. He laughed and gave in on the strap length. Their voices carried on the breeze.

I drove back to the house—not theirs, not anymore, not really mine either, more like everyone’s—and parked under the tree Leo used to climb as a kid because he dared Haley to and then had to prove it was “easy.”

In the foyer, Ky stood under the LEO printout with a clipboard. “We got three new reports today,” she said. “One from a warehouse in Ohio. One from a hospital in Texas. One from a distribution center in Jersey. Jules thinks we should do a webinar about shift-swapping coercion.”

“That’s specific,” I said, shrugging off my coat.

“We like specific,” Jules said, appearing from the dining room with a pencil behind her ear and a smear of flux on her cheek.

I grinned. “We do.”

We scheduled the webinar. We ordered Thai food. We argued about the best flux brand.

Life went on. Not like nothing had happened. Like everything had, and we refused to let it happen again in the same way without somebody yelling about it.

Years slid. Seasons tumbled over each other the way they do when you’re measuring time by cohorts and case files instead of calendars. Chloe, one of our second batch, left to start her own repair shop two towns over. She came back every few months for lunch and brought stories about customers who argued about prices and then came back anyway because “you’re the only one who explains it in English.”

Ky applied for a grant to build a mobile repair van—a literal school on wheels. When she got it, we painted the van ourselves on a weekend, words crooked but legible: FIX-IT FORWARD. Underneath, smaller: Powered by LEO.

Haley graduated from community college with a degree in occupational safety. She invited me and Mary to the ceremony. Mary declined. I went. When they called Haley’s name, she walked across the stage like her skeleton finally believed it belonged to her.

Afterward, in the parking lot, cap askew, she said, “I want to go into places like our plant. Before something happens. Not after.”

“Then that’s what you’ll do,” I said. “And you’ll be excellent.”

She blushed. “I learned from pros.”

One day, about eight years after I’d left the funeral with twelve dollars and nothing else, I found myself in my old Civic again.

I’d kept it. At first because I couldn’t bear to let it go—the car that had been my bedroom, my office, my kitchen. Later because it felt wrong to junk something that had carried so much weight. We’d parked it under a tarp near the back of the property, the tires flat, the cloth seats smelling like nostalgia and bad decisions.

Jules had been pestering me for months. “We could convert it,” she’d say. “Make it an exhibit. ‘How Not to Sleep.’ Or use it as a testbed for the EV conversion course.”

“You just want to take it apart,” I’d accuse.

“Obviously,” she’d say.

That afternoon, I pulled the tarp off and slid into the driver’s seat. Dust motes danced in the shaft of light cutting through the windshield. The steering wheel was faded where my hands had worn it smooth. The little crack in the dash from when we’d hit a pothole too fast on I-95 the day Leo and I drove to the ocean for the first time.

I turned the key out of habit. The engine did nothing, of course. But in my head, I heard the old cough, the determined rumble.

I ran my fingers over the spot where a piece of duct tape used to cover a tear. Memory and muscle layered over each other. For a moment, tears threatened. Not because I missed the hunger or the fear, but because I could feel, in my body, the woman who’d curled up on this seat and promised herself she’d never need any of them again.

She’d kept that promise. But along the way, she’d learned a better one: that needing people isn’t weakness. Needing the wrong people is.

I climbed out and found Ky and Jules arguing over a pile of scrap in the driveway.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s gut her.”

They whooped.

We wheeled the Civic into the garage. Hood up. Seats out. Wires exposed. We turned her into a teaching tool, a skeleton of a life that used to be my only shelter.

At the next cohort orientation, I stood beside the stripped car and told the story. Not the viral version. The real one.

“I slept here,” I said, knocking the roof gently. “I cried here. I ate way too many gas station burritos here. I thought… this was all life would ever be, because I had failed the test of ‘belonging’ my in-laws wrote.”

I saw their faces—hopeful, skeptical, guarded.

“I tell you this not because you should follow my path,” I said, “but because you need to know that the distance between where you are and where you want to be is made of small decisions, not magic. You will solder a joint wrong. You will mis-diagnose a board. You will think you’re not cut out for this. And then, one day, you’ll fix something no one else could and realize you’re the one people call when the thing they can’t live without stops working.”

I paused.

“They told me, in that family, that I hadn’t married well. That I hadn’t earned a seat at the table. They were right. I hadn’t married well. I married someone who died trying to support a system that didn’t care if he did. The only thing I can do now… is stop that story before it starts for as many people as possible.”

I looked at the Civic.

“This car got me through the worst years of my life,” I said. “Now it’s going to get you through the first ones of your new one.”

Ky started clapping. Jules joined in. Soon the whole room did. It wasn’t for me. It was for the possibility that their lives might be more than the script they’d been handed.

Part 5

The invitation arrived in a cream-colored envelope that smelled faintly of lilies and old paper.

For a second, standing in the foyer of the house I owned and everyone else still thought of as “the Welch place,” I was twenty-one again in a borrowed dress, waiting for Mary to pronounce judgment on whether my shoes were “appropriate.”

Then I flipped the envelope and saw the return address: Welch Industries Memorial Foundation.

I laughed. I couldn’t help it. The sound bounced off the high ceiling and came back at me like a heckler.

“Everything okay?” Haley called from the kitchen.

“Depends on your definition,” I said, walking in.

The envelope held a heavy card stock invitation, embossed with a logo some overpaid designer had clearly pitched as “classic with a modern twist”: intertwined W and I with a little laurel wreath. The text was formal.

You are cordially invited to attend the inaugural Leo and Julius Welch Memorial Lecture on Ethical Innovation.

Keynote speaker: Logan Welch.

“Ethical,” I read aloud. “Innovation.”

Haley dropped the spoon she was using to stir her tea. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

“Apparently he got the speaking tour he wanted,” I said.

Brian, who’d come over to fix a glitch in our server, snatched the invitation and read it. “They booked a conference center downtown,” he said. “They’re charging a thousand a seat.”

“A thousand?” Haley yelped. “To hear him talk about ethics?”

“He’s out,” I said. Saying it out loud made it more real. He’d been paroled eighteen months ago. I hadn’t gone to the official hearing to hear the decision. I’d read it online like everyone else.

He’d stayed quiet since. No interviews. No public statements. No visits to the co-op. This lecture would be his reentry.

“You going to go?” Brian asked.

I traced the raised letters on the card. Leo and Julius. They’d slapped his name on the front of an event he never would have attended.

“No,” I said. “We are.”

We bought three tickets with LEO money, because sometimes you need to see a system up close to understand how to dismantle it.

The night of the lecture, the hotel ballroom hummed with the low, expensive murmur of corporate networking. People in suits milled around high-top tables, wine glasses in hand. A banner with the foundation logo hung behind a stage lit too brightly.

We took seats halfway back. Close enough to see his face. Far enough that I could leave without climbing over anyone if I needed to.

A woman in a sleek black dress introduced him.

“Tonight,” she said, “we welcome a man who has learned from his mistakes. Who has turned personal tragedy into a commitment to ethical leadership. Please join me in welcoming Mr. Logan Welch.”

He walked out to polite applause.

He looked older. We all did, but on him it showed in deep lines around his mouth, in the way his shoulders hunched slightly like he was bracing for a blow that might not come. His hair was mostly gray now. No suit—just a white shirt and dark slacks, the uniform of someone trying to look humble on purpose.

“Thank you,” he said, gripping the podium.

He started with the script I expected. “I used to think success was numbers on a page,” he said. “Account balances, stock prices, square footage. I measured my life in quarterly reports.”

People nodded. They recognized the language.

He talked about “losing his way.” About “failing to see the human cost.” About “the night everything changed.” He mentioned “my brother” several times, each time pausing as if the words required effort.

Beside me, Haley whispered, “He cried in the shower when he said yes to Mom about cutting the safety audits. He thought no one heard. I did.”

On stage, he said, “I’m not here to excuse what I did. I’m here to tell you it’s possible to choose differently.”

He clicked to a slide showing a graph trending upward, labeled HUMAN FIRST. I almost choked.

“This is… surreal,” Brian whispered, scribbling something on his notepad that I later saw was a tally of every time Logan said journey.

“Listen,” I murmured.

Because underneath the buzzwords and the rehearsed pauses, something felt… off. Or maybe on, in a way I hadn’t anticipated.

Midway through, he stopped. Put both hands flat on the podium. Looked directly at the center camera that was beaming his image to a livestream audience of paid attendees.

“There’s something else,” he said. “Something I didn’t tell the board. Or the press. Or anyone except my therapist and the guy who refused to ghostwrite this speech for me.”

The room shifted. People glanced at each other. This wasn’t on the handout.

“I’ve been using ‘we’ a lot,” he said. “‘We cut corners. We didn’t see. We failed.’ What I really mean is ‘I.’ I failed. I cut the corners. I ignored the reports. I signed the documents. When my brother died, I told myself it was a tragic accident. It was easier than admitting I’d written the conditions that made it possible.”

Silence. No clinking glasses. No murmurs.

“In prison, I saw a website with his name on it,” he continued. “Just Leo. No last name. Stories like his. Wives and husbands and kids and friends saying ‘he went to work and didn’t come home.’ I saw my name. Not on the site. In the patterns.”

He exhaled shakily.

“That site exists because my sister-in-law”—he didn’t say my name; didn’t need to—“was left with twelve dollars and more debt than anyone should have. She didn’t accept a martyr. She built a movement. I’m not the hero here. I’m the warning.”

He paused. Looked out over the room.

“You all paid a lot of money to be here,” he said. “To hear how to be ethical without sacrificing profit. To learn how to do the right thing without making anyone uncomfortable. I can’t give you that. There’s no version of this where you keep everything you have and your people stop dying. You’re going to have to give some of it up.”

A nervous laugh from someone at a side table.

“I’m not naïve,” he continued. “I know some of you will leave here feeling moved and do nothing. Some of you will quote me in your annual reports and never change a single schedule. But maybe… one or two of you will go back and pull a shift report or a budget ledger and say, ‘Not on my watch.’ That’s who I’m talking to.”

He stepped back from the podium.

“I’m done being asked to tell a redemption story,” he said. “There is no redemption for what I did. There is only restitution. And that’s not something you clap for. It’s something you pay for.”

He walked off stage.

The room sat in stunned silence for a full thirty seconds before the automatic polite applause kicked in, weak and scattered.

“Was that… real?” Haley asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “But it was useful.”

Later, as the crowd thinned and people went back to exchanging business cards as if nothing had tilted, Logan approached us.

He looked smaller up close. Or maybe I was finally seeing him without the scaffolding of power.

“Hi,” he said.

“Hi,” I replied.

Haley crossed her arms. “Nice speech,” she said, the words edged.

He nodded. “I didn’t tell them I was going to say all that,” he admitted. “Pretty sure I’m not getting invited back.”

“Good,” Brian said before he could stop himself.

Logan gave a short, tired laugh. “Yeah,” he said. “Good.”

He looked at me.

“I know you don’t owe me anything,” he said. “But I wanted to say… I’m sorry.”

The words were inadequate. They always are. They don’t raise the dead. They don’t erase hospital bills. They don’t clean the blood off the ledger.

But he wasn’t offering them as a check. He was naming them as a receipt.

“I’m not the one you need to say that to,” I said. “You need to say it to every person who punched in under your watch. To every spouse who sat in a waiting room and heard ‘these things happen.’ To yourself, in a way that changes how you move.”

“I’m trying,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “Keep doing it where it counts. Not on a stage.”

He nodded. “I’m working with the co-op,” he said. “Pro bono. Well, just… bono, I guess. They make me take notes.”

“They should,” I said. “Trina will eat you alive if you step out of line.”

His mouth twitched. “She already did,” he said. “Twice.”

We stood there for a moment. The air between us was neither forgiveness nor hatred. It was something stranger: acknowledgment.

“I don’t expect you to forgive me,” he said finally. “Ever.”

“Good,” I said. “Then we’re on the same page.”

We left it there.

Outside, the air was cool. The city lights blinked. Cars honked. Somewhere, a siren wailed. Life, uninterested in our dramas, went on.

Back at the house, Ky and Jules had ordered pizza and were watching a documentary about right-to-repair laws. They made room on the couch. Haley kicked off her shoes and tucked her feet under her.

“How was the show?” Ky asked, mouth full.

“Underwhelming and unexpectedly useful,” I said.

“Metaphor for capitalism,” Jules muttered.

We laughed.

Later, in my small back room with the west-facing window, I opened my laptop and pulled up the LEO site. A new submission had come in while we were at the lecture.

Heard your story on a podcast. I thought it was just us. My wife says I should tell you what happened at our plant…

I read, and my chest tightened, and I forwarded it to the lawyer and to Trina and to Haley with a note: next.

Because that’s what justice looked like now. Not a finish line. A relay.

I lay down and looked at the ceiling. The cracks formed shapes if you stared long enough. Leo used to see dragons. I saw circuit diagrams.

The house was quiet, but not the brittle quiet of grief. The full quiet of rest. Down the hall, someone snored softly. The pipes hummed. The fridge kicked on.

I thought of that day at the funeral. Twelve dollars in my pocket. A pine box I couldn’t afford. A family that looked at me like a failed audition.

I thought of the Civic. The Exxon lot. The first phone I took apart with hands that shook from caffeine and rage.

I thought of the woman who’d come to the door that morning asking if she was too old to learn.

I thought of Ky’s van. Of Haley’s degree. Of Brian’s pizza drawings. Of Logan’s face when he said I’m sorry like he understood it wasn’t a spell.

I realized, suddenly and simply, that I wasn’t carrying it all anymore. The weight had been distributed. Spread out over circuits and circuits of people who’d decided they were done being quiet.

I had left with twelve dollars. They had expected me to crawl back, to beg, to be grateful for scraps.

Instead, I learned to read the bones of their machines and their ledgers and their lies. I learned to build something that didn’t require anyone’s permission.

Two years later, I bought their house in cash.

Ten years later, the house no longer felt like theirs. Or mine.

It felt like a promise kept.

Some nights, when the air is just right and the noise level in the house drops to that sweet spot between chaos and silence, I stand in the foyer and listen. I can almost hear Leo’s voice, not as a ghost, but as an echo in the structure.

“And here,” he’d say, “you see the underdogs take the lead in the final quarter. The crowd didn’t see it coming, but anyone paying attention knew the whole time the game was rigged—and still, somehow, they won.”

I smile and flip off the light.

Tomorrow there will be more devices to fix, more reports to read, more girls to teach, more men to testify against and sometimes, rarely, for. There will be more grief. More joy. More mundane Tuesday afternoons where nothing happens except someone learns to trust their hands.

Justice turned out not to be a destination.

It was a daily practice.

And so, with every joint soldered, every story documented, every shift refused, every young woman who walked into a room she’d been told wasn’t for her and sat down anyway, we kept at it.

One steady, hand-soldered connection at a time.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court

HOA Put 96 Homes on My Land — I Let Them Finish Construction, Then Pulled the Deed Out in Court…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It Part 1 The email hit my inbox like…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”? Part 1 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last Part 1 The…

Karen Lost It When I Bought 50 Acres Outside the HOA — My Locked Gate Blocked Her Forever

When I bought 50 acres just outside the HOA’s reach, Karen thought she could still control me. But the moment…

German Officers Never Expected American Smart Shells To Kill 800 Elite SS Troops

German Officers Never Expected American Smart Shells To Kill 800 Elite SS Troops December 17, 1944. Elsenborn Ridge, Belgium. SS…

End of content

No more pages to load