Part 1

The scent of lilies and stale grief clung to me like a shroud. I stood in front of the cheapest pine coffin they could find and whispered, “I’m so sorry, Leo.” My voice cracked on his name.

Leo Welch. My husband. Gone at thirty-three. I was thirty-one, and it felt like we’d lived three lifetimes together and still hadn’t gotten to the part where things got easy.

The funeral director—professional in black, his brow fixed in that permanent tilt of sympathy—cleared his throat. “Mrs. Welch, we’re ready to finalize the arrangements.”

Every head in the small chapel turned to me. At the front, Leo’s mother, Mary, stiff in a gray suit, looked at me with the same expression she’d worn since the day we met: like I was a stain she couldn’t quite scrub out. Her eldest son, Logan—thirty-five, and the self-appointed guardian of the Welch “legacy”—stood beside her with his arms crossed and a smirk playing on his lips. His wife Olivia clutched her handbag like she expected me to try and steal it. Haley, the youngest at twenty-eight, didn’t look up from her phone.

“Payment, Mrs. Welch?” the director prompted again, his voice softer now.

I had twelve dollars in my pocket. Twelve. Hospital bills had eaten our savings. Leo’s paycheck had stopped the day his heart did. My own work had dried up in the weeks I spent in hospitals and waiting rooms. I hadn’t told anyone that I’d sold my laptop to keep the lights on for those last two weeks.

Before I could answer, Mary stepped forward, her voice slicing through the hushed air. “Honestly, Cameron, you should have married someone with more foresight. Someone who could afford to bury their husband properly.”

Logan chuckled. Haley glanced up, smirked faintly, then dropped her eyes back to the glowing screen in her hands.

The humiliation scorched hot up my neck. My own parents sat in the second row; my mother twisted her hands together, my father stared at the floor. Later, they would tell me it was time to “come home” and “start over” like I was a teenager who’d gotten in over her head at college, not a widow who’d just buried her husband.

I didn’t answer Mary. I didn’t answer the funeral director. I turned on my heel and walked out, my backpack heavy on my shoulders, the weight of those twelve dollars heavier still.

My Honda Civic was waiting in the lot, paint faded, the engine coughy from years of Leo’s patient maintenance. I started it, not looking back at the chapel, and drove until the city lights shrank to a glow in the rearview mirror.

That night I parked behind an Exxon station. The smell of fuel and burnt coffee drifted through the cracked window as I lay back in the seat. Twelve dollars. That was it. I could stretch it for maybe two days if I rationed coffee and gas station ramen.

I swore, in that thin slice of pre-dawn, that I would never need any of them again. Not his family. Not mine.

The twelve dollars ran out in forty-eight hours. After that, the Civic became my everything—bedroom, office, kitchen. I rotated parking spots: Walmart lots, quiet side streets, the back edges of industrial parks. Always with one eye open.

Days, I camped at the public library. Free Wi-Fi. Bathrooms with warm water. A corner table where no one looked too closely at how long I stayed. At first I just… scrolled. Anything to drown out the grief and the shame. One afternoon I clicked on a YouTube video of some kid disassembling a phone—logic board laid bare, tiny screws lined up like soldiers. The precision mesmerized me.

Leo used to joke that I had X-ray vision for electronics; I’d fixed his old laptop with nothing but a borrowed screwdriver and a blog tutorial. Watching those videos, something clicked. My hands knew how to do this.

I started collecting broken devices from dumpsters and curbs: shattered-screen phones, dead tablets, old laptops. I bought a cheap toolkit with my last few dollars. The backseat of the Civic turned into a miniature repair bench. At night, under a headlamp, I practiced: prying open cases, swapping out charging ports, teasing tiny ribbon cables free without tearing them.

Two months in, I could diagnose a dead motherboard just by looking at it. I joined obscure repair forums, posting under “Cameron R,” helping strangers troubleshoot just for the challenge.

That’s when the message came—from a user called “BiteKing.”

Saw your posts on the deadboard revival thread. Got a job for you if you want it. High risk, high reward. Cash.

The photos he sent looked hopeless: a motherboard waterlogged and charred, the kind of job most shops wouldn’t touch. He called it “critical data recovery.” I called it a chance.

Three days in the Civic, hands cramped, back screaming, fueled by gas station coffee—and the data flickered to life. BiteKing, real name Brian Carter, paid me more than I’d seen in months. Enough for better tools, a P.O. box, and a warm meal that wasn’t shrink-wrapped.

“You’re good, Cameron,” Brian said over an encrypted call. “Ever thought about going pro? Anonymously?”

That’s how Vexa was born.

Vexa had no face, no real name—just a reputation in the dark corners of the internet for fixing the unfixable, recovering the unrecoverable, bypassing whatever others called impossible. Jobs came through encrypted channels, payments in untraceable transfers. The work was high risk, but the reward… I was finally building something.

One night, a new request pinged through: Project Red Tears. Corrupted surveillance system. Colonial estate. Cash buyer wanted the system audited and vulnerabilities exposed.

The address in the specs made my hands still on the keyboard. The Welch family home.

I dug. Property records showed “urgent sale—cash buyers preferred.” Deeper still, and the picture emerged: Logan had sunk the family trust into a disastrous crypto play. The house was collateral. They were desperate.

Two years after leaving that funeral with twelve dollars, I wasn’t just surviving. I had the skills. I had the money. And now, I had the perfect opportunity.

Part 2

I didn’t sleep the night after I handed Mary the motel key. I lay on the floor of the empty study—the only room that didn’t echo my footsteps—and watched moonlight crawl the wall where her wedding portrait used to hang. It wasn’t triumph that kept me awake. It was the drum of everything that came next.

Justice is never a single event. It’s a ledger you audit, number by number, until the balance is true.

By morning, the headlines had multiplied. Welch Industries CFO Under Investigation as Widow Questions Circumstances of Husband’s Death. Olivia’s influencer friends pivoted from deifying her pool parties to dissecting her “cruelty”—a word that looked strange beside someone who cried at perfume commercials. Haley’s text pinged at 6:12 a.m.

I’m sorry. I can help you clean it up. I don’t want to be them anymore.

I stared at the words until the phone dimmed. Then I went downstairs and made coffee on a camp stove because the gas service still sat in some limbo of legal paperwork. I drank it on the back steps where Leo and I used to sneak away during holiday dinners to breathe.

He’d sit on the top step, elbows on his knees, and narrate the night like a sports commentator.

“And in the southeast dining room,” he’d murmur, “the eldest Welch male makes a risky attempt to monologue about interest rates while his wife’s face indicates she would rather eat the china.”

Back then I thought the laughing made it survivable. Now I knew it only turned down the volume.

I texted Haley one line: Come at noon. No phones.

She arrived five minutes early in a hoodie and sunglasses, hair knotted on top of her head like she’d yanked it up with both hands. Up close, the veneer cracked: bitten cuticles, a constellation of stress acne along one cheek, a bruise-yellow crescent at her temple she tried to hide with concealer and failed.

“Fell into a cabinet,” she said when my eyes found it.

“Logan?” I asked.

Her face tightened, and she didn’t answer.

We sat in folding chairs in the empty parlor like two kids in trouble. I set a recorder on the mantelshelf, its red eye blinking. “I’m not interested in ruining you, Haley,” I said. “But I need the truth in the record.”

She took a breath like someone about to swim the length of a pool underwater. “I thought the money made us safe,” she said. “I thought… if I just didn’t look at the ugly parts, they couldn’t touch me.” Her mouth twisted. “Logan said Leo was weak. That he took the wrong shift, that he didn’t follow protocol. He said… it was sad, but these things happen. When I saw the policy date, I knew. I knew it wasn’t an accident to them. It was arithmetic.”

The recorder kept blinking. Outside, wind scraped the boxwoods against the windowsill.

“Mary called it ‘a provision,’” Haley continued. “Said real grown-ups prepare for worst-case scenarios. The night of the accident, she told the ER doctor we wanted ‘comfort measures only.’ She said Leo wouldn’t want machines. She didn’t ask you because you’d ‘fall apart and embarrass everyone.’ When you got there, she kept you in that glass room and told the nurses not to let you back. I—”

Haley’s voice broke. She pressed a fist to her mouth and inhaled hard through her nose. When she spoke again, it was smaller. “I tried to text you. Logan took my phone.”

He would have. He was always better at catching things than throwing them.

I reached up and clicked the recorder off. “Why tell me now?”

“Because you didn’t just burn their house down,” she said. “You lit up the whole street so I could see. I’ve been living in a room with no windows.” She swallowed. “I don’t know how to live somewhere else. But I want to.”

I believed her. Maybe because there was no performance left in her. Maybe because I could see the kid she used to be—awkward and too tall, hiding behind an older brother who’d weaponized her invisibility.

“You’ll write a statement?” I asked.

She nodded. “I’ll sit for whatever you need. I’ll testify. I’ll… I’ll pay back what I can. I don’t have much, but—”

“I don’t want your money,” I said. “I want your memory. The parts nobody recorded.”

She flinched at that and then nodded again like a soldier.

When she left, she hugged me. It wasn’t pretty. It was a clumsy collision of elbows and apology. But it was the first thing anyone in that bloodline had given me that didn’t come wrapped in contempt.

Brian sent me a message with a link to a shared drive and a single sentence: You ready to go loud?

“Loud” in Brian-speak didn’t mean press conferences or weepy videos addressing “the community.” It meant something precise: documented, timestamped, corroborated. It meant we weren’t asking anyone to believe us; we were asking them to read.

We published a dossier. Not to tabloids, not to Jolie’s parasitic audience, not even to my personal accounts. We filed it as a complaint with the Department of Labor and OSHA: negligence, financial coercion, ethical breaches in medical decision-making. We attached affidavits from Haley and two anonymous plant workers who’d been waiting for somebody—anybody—to go first. We included copies of the budget cuts, the policy date, the email from Mary with provision in the subject line, the redacted medical report with its redaction undone.

And then, because some truths need to breathe outside meeting rooms, we mirrored the dossier on a public site—a simple page with a single header: LEO.

No last name. No dramatics. Just the person they tried to erase.

By sundown it had a hundred thousand views. By noon the next day, five hundred thousand. Reporters called. Lawyers called. A woman I didn’t know in a town I’d never visited sent a voice note that began, “My husband died on a shift he shouldn’t have been on. When I asked why, they told me the schedule was fixed.”

I didn’t reply to any of them that first day. I sat on the back steps again and watched two girls from our new training cohort kick a soccer ball across the lawn where the caterers used to set the rented tent. One girl had her hair in blue braids. The other wore a neon hoodie and boots scuffed white at the toe.

They laughed the way teenagers do, hard and free, like sound itself was a resource you couldn’t ever exhaust.

When the ball hit a yew and ricocheted toward the porch, the girl in the hoodie chased it and skidded to a stop when she saw me. “Sorry!” she said, half-gasping.

I picked up the ball and spun it on my palm. “Tell your coach to move the cones a foot to the left,” I said. “Wind’s pushing your shots.”

She squinted at me. “You’re not the coach.”

“More of a groundskeeper,” I said. “But I pay attention.”

Her grin flashed like a match. “I’m Ky,” she said, and held out a hand. “The blue braids is Jules. We’re on the PCB repair track. Jules says she’s going to be better than you in a month.”

“Jules should aim higher,” I said, tossing the ball back. “I’m only good because I was hungry.”

They took off, already laughing again, the ball banging off one of the stone lions flanking the terrace. The lion blinked in the sun like a creature just waking up.

Mary filed a defamation suit. Of course she did. It had two causes of action: reputational harm and intentional infliction of emotional distress. Brian sent me a PDF at 2 a.m. with a subject line that only read: lol.

He told me not to worry. I didn’t, exactly. But in the hours before dawn, I sometimes imagined the old Mary, the one from when Leo was a kid—the one who took him to the museum on Tuesdays because admission was free. Had she ever existed? Or had grief erased her before grief even arrived?

When the suit made the docket, it also made the morning shows. Which meant the morning I walked into a courtroom again, I did it in front of cameras. My palms didn’t sweat. My heart didn’t sprint. I’d already done the hardest thing anyone ever asked me to do: leave with twelve dollars and not come back.

Mary wore gray again and a new set of pearls—as if pearls could make a different argument than the one her face made. Logan wasn’t with her. He was working the only strategy left to him: hide and hope the fire burns out.

The judge was a woman in her fifties who had the patient fury of a person who’d read too many pages of preventable damage. She let Mary’s lawyer talk for twelve minutes uninterrupted, then held up a hand. “Counsel,” she said, “your client’s problem is not defamation. It is documentation.”

Brian leaned over and scribbled something on his legal pad. It was a tiny pizza with a speech bubble that said, Objection: cheesy. I snorted, too loud for court. The judge cut me a look that was not unkind.

“You want to keep going?” Brian whispered.

“We are going,” I said. “With or without a gavel.”

The suit died where it stood. I walked out into sun sharpened by winter air and a sidewalk full of microphones and didn’t say anything into any of them. A younger me would have. She would have wanted the last word, the ten-second clip that played well in strangers’ living rooms.

I’d learned something in the months since I became Vexa, and then stopped needing to be. Silence is not absence. Sometimes it is a structure you build so the truth has somewhere to sit.

I went to see Mary at the motel the night before the sheriff’s sale of the condo I’d bought, then sold, then re-purposed, then let go of entirely. I brought her a bag of groceries and a flyer.

She answered the door with her mouth already open like a pitcher.

“You’re not welcome,” she began.

“It’s not your house,” I said. “You don’t get to decide who’s welcome in rooms you don’t pay for.”

She tried to slam the door. I stopped it with my palm and the quiet force of someone who’d learned to carry weight without showing it.

“Mary,” I said, and the name came out of me with no malice in it, which shocked us both. “I brought eggs and soup and bread. I brought a flyer for a grief group that meets two blocks over on Tuesdays because that’s still your day for free things.”

Her eyes flickered. The muscles in her jaw flexed. “You’re enjoying this,” she said.

“I didn’t enjoy any of it,” I said. “Not one minute.” I held the flyer out. She didn’t take it, so I set it on the nightstand inside the door. “There’s a number on the back for an advocate at the hospital,” I said. “You’re going to get asked questions you won’t want to answer. Call her before you answer them. You’re going to need an attorney who doesn’t lie to you. I wrote down names.”

Mary’s mouth clicked shut. She looked at the bag of groceries like it was a trick.

“You think this makes you better than me,” she said finally.

“No,” I said. “I think it makes me done.”

I stepped back into the hall. “You can hate me,” I said. “I won’t give it back.” And then I walked away.

In the parking lot I sat in the driver’s seat a long time without turning the key. The motel neon bled red on the glass. I remembered Mary standing at the foot of the hospice bed with her hands folded like a schoolgirl praying to the wrong God. I remembered Leo’s breath rattling. I remembered the way the nurse cut off the oxygen alarm with her thumb and how small the room felt when a machine stopped arguing with the air.

No, I didn’t enjoy any of it. But joy isn’t the only measure of whether something matters.

The LEO site became more than a complaint. In three months, we had fifty-seven reports from workers in three states. Brian built the database because he liked to pretend he didn’t care and then do the kindest thing you could imagine without telling anyone. Haley ran intake. She was good at listening without filling the quiet. She learned to say, “I hear you,” instead of “I’m sorry” because some things deserve mirrors more than bandages.

Ky and Jules got their first contracts repairing logic boards for a refurbisher who paid on time and in cash. The day Ky brought me a check with her name on it and zeros she’d earned, she cried in the kitchen, and then laughed, and then cried because she’d laughed while she was crying like it meant something was wrong.

“It means everything is working,” I said. “All systems normal.”

We hosted our first class in the dining room with the table leaves removed and anti-static mats lined up like a runway. Twelve women, ages nineteen to forty-three, learned to wick and reflow and test for shorts. Someone burned a finger. Someone soldered to the wrong pad. Someone who’d never been told she could be good at anything lifted a microscope, found a hairline crack, and whispered, “I see it,” like a prayer.

I hung two photographs in the foyer where the oil portraits had glowered for decades: one of the girls playing soccer, all elbows and knees and laughter; one of Leo in a thrift-store suit on our wedding day, crooked tie, crooked grin, holding a bouquet he’d made himself from grocery store tulips and a sprig of rosemary because it “smelled like brave.”

On the anniversary of his death, I took the second photo down and brought it to the graveyard. I sat on the grass, not caring that the ground was cold or that my coat wasn’t warm enough.

“They read it, baby,” I said to the stone. “They finally read it.”

Wind moved through the oak above me with a sound like distant surf. A crow landed on the far corner of the fence and swore at me for invading its afternoon. I reached into my pocket for the thin brass key I kept there—a relic from the condo, not because I needed souvenirs but because I needed reminders. I set it on the dirt and pressed it down until the earth took it.

“I don’t need doors,” I said. “I build openings.”

I stayed until my fingers went numb and then I went home.

Six months after we published, Welch Industries declared bankruptcy. The plant was bought by a cooperative, half the board made up of workers who’d punched in there for twenty years and knew which motors sang and which ones were about to burn. They rehired more than anyone thought they would.

Logan took a plea deal on the financial crimes. He won’t go to prison forever, because this isn’t a movie, but he will be poor, and he will be ordinary, and that may be a worse sentence for someone who thought money made the mirror tell the truth.

Mary’s defamation suit vanished into that long night where bad ideas go. She moved into a one-bedroom apartment on the bus line and, according to a whisper routed through a cousin who still speaks to everybody, she goes to the Tuesday group sometimes. I don’t need to know whether she talks. It’s enough that she sits in a circle where someone could look at her and say, I hear you.

Haley started taking classes at the community college. She texts me pictures of her notebooks: margins filled with doodles of circuits and little cartoon lungs with sparkles around them because she says breathing is a hobby now. Sometimes she comes over and helps Ky and Jules with their homework, and they roll their eyes because “ugh, Haley,” and then ask if she wants to order dumplings and not tell me how many.

I still fix things, but not for ghosts. Vexa exists the way a retired knife exists: sharp if you touch it wrong, not interested in shining. Sometimes I take a job because a stranger says “please” like a person drowning, and sometimes I send it to one of the girls because their hands are steadier than mine now and that makes me proud in a place so deep I don’t have a name for it.

I got a letter from Leo’s great-aunt’s lawyer—the one whose estate Logan had tried to disappear. It was handwritten and smelled like violet talc when I opened it, a ghost of the woman who’d saved catalog clippings and cash in freezer bags. I always hoped the right person would find this, the letter said. I don’t know who you are, but if you found it, you’re the right one. Make something better than a trust fund.

I taped it inside the supply closet door where the girls keep the isopropyl and the Kapton tape and the box of band-aids for when someone forgets that heat is not an idea. Every once in a while someone reads it and says, “She sounds like my grandma,” and I say, “She sounds like everybody who ever put five dollars in a coffee can and said ‘someday.’”

On a warm night the following spring, I hosted a dinner. Not a gala, not a fundraiser, not a press event. A dinner with folding tables and mismatched plates and food that steamed in the cool air. We ate outside under strings of cheap bulbs because the expense of a chandelier is a tax on people who don’t know how good the sky looks.

Brian came and pretended to be uncomfortable around so much sincerity and then laughed at one of Ky’s terrible jokes until he had to put a hand on the table to breathe. Jules’ mother brought arroz con pollo and three types of pickled onions. Haley made a cake that collapsed in the middle and then declared it a crater and filled it with berries like a tiny universe.

After we ate, we played music from someone’s phone and danced on the flagstones with the caution of people holding full cups and full hearts. I am not a good dancer. I move like someone trying to get a very determined cat off a countertop. It didn’t matter.

At some point I walked away from the noise and stood on the back steps again. The lawn rolled down to the trees, the trees held up a slice of moon, and for a second the house didn’t look like a house. It looked like a possibility that had gotten tired of waiting to be used.

I felt a presence beside me—not the kind you have to pretend about, not the kind you conjure because it hurts less than the alternative. Just the simple awareness of space making room for memory.

“I did it,” I said.

The wind moved across the grass.

“And I didn’t do it like they would have,” I added, because that mattered to me. “I didn’t become them on my way to outliving them.”

Behind me, laughter spiked, then fell into a hum. Someone must have spilled something, because a chorus of “oh no” rose and then turned into “it’s fine” like a blessing.

I turned back toward the noise—the clatter and the voices and the light—and realized I was no longer measuring my life by what I’d lost, or what I’d taken back. I was measuring it by what I was building.

For months, I’d been thinking in closures: cases closed, accounts closed, doors closed. But that night the word that came to me was simpler and bigger.

Open.

Open like a ledger finally balanced. Open like a window after a long winter. Open like a door you hold for someone behind you because someone held it for you once, when you had twelve dollars and more debt than hope.

At the very end of the night, after the dishes were stacked and the last car’s taillights were a smear on the road, I walked into the foyer and looked up at the place where Mary’s portrait had glared down on generations of Welches who learned how to perform before they learned how to tell the truth.

I hung a new frame there—a printout of the LEO header page, corners held by brass tacks because ornate frames are cages. Under it, I taped a quote Ky liked to write on her notebooks: The digital bones always tell a story. You just have to know how to listen.

I locked the door and went upstairs to the small room I kept at the back of the house. The window looked west. I brushed my teeth with the bathroom light off because the moon was bright enough. I lay down and fell asleep fast, without dreaming, which felt like a luxury so grand no one had invented a price for it yet.

In the morning, the house woke before I did. Somewhere downstairs a microwave door clacked; a kettle hissed; a girl with blue braids scolded a girl in a neon hoodie for using the good tweezers to open a bag of chips. I smiled into the pillow.

I’d left with twelve dollars. I’d come back with less than that and more. The house didn’t matter anymore because a house is just a container. What mattered was what we’d poured into it: tools and time and tenderness and truth, the four currencies nobody can repossess.

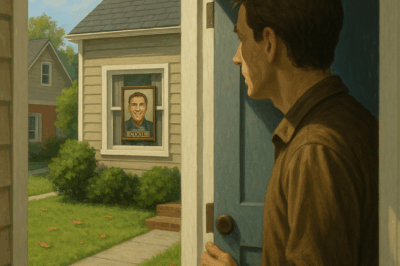

On my way to the kitchen, I passed the front hall and saw a woman on the porch, mid-fifties, posture like a question. She wore a coat too thin for the morning and her hands were empty.

When I opened the door, she startled, then steadied.

“Is this the… the training place?” she asked.

“It is,” I said.

“I saw the thing online,” she said. “The… the Leo site. I don’t know if I’m too old for this kind of work.”

“You’re not,” I said.

She nodded, eyes wet but not weeping. “I’m tired,” she said. “But I’m not done.”

“Good,” I said, stepping back, holding the door. “Neither are we.”

She came in past me, shoulders squared a fraction. I closed the door against the cool, and inside we set water to boil, and turned on the lights over the mats, and made room at the table.

Justice had been served in full. Mercy—unexpected, undeserved, unasked for—found whatever space was left and sat down with us, picked up a screwdriver, and got to work.

I had left with twelve dollars. Two years later, I bought their house in cash. And in the years after that, we bought a better future together, one steady hand-soldered joint at a time.

END!

News

My neighbor had the coolest name I’ve ever heard. Then he died.

Part 1 Hello my friends, I’m not really sure how to get started. But I had something exceptionally bizarre happen…

Help. It’s 7:58am Again And It Will Be Until She Smiles

Part 1 I don’t know where else to put this. I’ve called 911. I’ve broken windows. I’ve tried staying awake…

20 years ago, a child went missing. 2 months ago, I found him.

Part 1 I don’t know what I’m doing posting this to a damn internet forum, but I need to get…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Part 1 The email hit my inbox like a punch to the gut. Not the email itself, but the attachments—screenshots…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

Part 1 of 2 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived like a digital slap—a sloppy forward from…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Part 1 The cream‑colored envelope felt heavier than paper ought to. It wasn’t just the cardstock—my family preferred thick things,…

End of content

No more pages to load