Part 1

Ding.

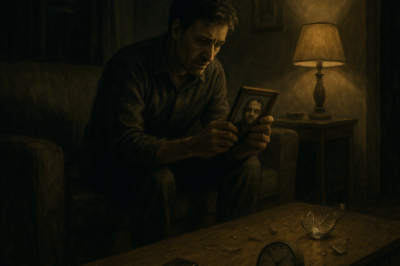

I wasn’t even properly asleep—just suspended in that humming limbo where the news read itself to no one and the TV light washed the living room the color of a fish tank. I lifted my face off the sofa arm and squinted at the rectangle on my chest. An unknown number. A question.

This or That? Tea or Coffee?

I laughed once, that little bark you give a minor annoyance to keep it minor, and set the phone face down. Spam, I told myself, or some idiot’s idea of a viral game. I shut the ringer off and already felt myself falling again when the phone—a dead, black slab—lit my shirt with white.

This or That? Tea or Coffee?

The sound cut through the show, the room, the little membrane of sleep I had growing around me. I slid my thumb along the side button until the screen winked out completely. Power off. There, I thought, there, go away. I shifted. The couch breathed. The apartment settled. I closed my eyes.

Ding.

My eyes snapped open. The phone was still dark—off—but text sat on it like handwriting on a chalkboard. Impossible, bright, the glow coming from nowhere.

This or That? Tea or Coffee?

There are ways you can frighten a person at ten p.m. that don’t work at noon. A light in the wrong direction. A sound at the wrong distance. A message from something that isn’t supposed to be alive when you’ve turned it off. A cold, unreasonable anger stood up in me before fear did. I thumbed the power on. The phone woke like a dog forced from sleep. My thumbs fed the number something venomous—spam, scam, leave me the hell alone—and then stopped. The urge to answer it properly slid into me like a coin going down a throat.

Fine. You want a choice? I’ll pick.

I typed Coffee and hit send, and the relief was immediate and stupid. A switch you flip. A task checked.

Morning ran its routine over me until I hit the gap in it. I padded into the kitchen on autopilot, opened the cabinet for the bag of beans.

“Where did I…” I muttered, and frowned into the empty corner of the shelf where my hand always landed. I checked the other cabinet. The freezer. The breadbox, because why not be insane about it.

I got cranky without coffee. I told myself I’d mis-shelved. My brain, still an animal trying to find the path in tall grass, tried loops I’d run before. When I came up with nothing, I grabbed keys and went to Lucci’s.

Lucci’s is the kind of neighborhood place you narrate to friends as proof you live in a neighborhood. Luca behind the counter knew me. He knew my order. We had a script.

“The usual,” I said, already smiling into it.

He looked at me like I’d brought a goat on a leash into the shop. “The… usual?”

“Yeah. The—” I mimed raising a cup. “Small—”

He stared another beat. “Small tea?”

It took my brain a second to rotate the idea. “No, I—coffee.”

Luca blinked. “Coffee?”

He said it like it was a word he didn’t use. The chalkboard menu behind him listed pastries, Tea Flights, Herbal, Black, Green, Matcha. The chalk where COFFEE should have been was bare.

“Are you okay, man?” he asked gently.

“Did you—did you change the menu?”

“I mean, we sometimes—”

“No, no. Like… do you not… sell coffee anymore?”

He watched me like you watch someone bracing to run into a wall. “We’ve never sold coffee,” he said carefully.

It was the way he said never that made it not a practical joke anymore. Never had that slight flinch in it, like the body making room for rewiring. The word did a strange thing to my stomach. I left without ordering. A woman at a table by the window sipped her tea and frowned at me as if I’d farted loudly in the middle of church.

In the office, I googled coffee like a lunatic proving elephants exist. The results were… well, there were results. But the pictures were sepia weird. Headlines said things like Caffeinated Leaf Steeps High in Popularity and Beans? No Thanks. Old blog posts referenced coffee the way people talk about moon shacks in conspiracy forums. Wikipedia had a stub: Coffee—a mythical beverage rumored to be brewed from roasted seeds; discredited; see Tea. I scrolled, laughing that laugh where it’s not funny and then your throat tastes like copper.

At my desk, I stared at my mug—the one my sister had given me with a dumb pun about Mondays—and its absence told me what the word never had. The mug now said TEA YOU LATER and I hated it with a fresh, precise passion.

I didn’t make the connection until later. We don’t let our brains wear socks with sandals on purpose. We prefer accidents to the right story told too early.

The second text threaded itself into that denial cleanly as dental floss.

This or That? Luna or Sol?

I was on the floor, elbow-deep in the back of a closet I’d already checked twice for the phantom bag of beans that never was, when the ping vibrated on the hardwood. I picked up the phone and felt my face go cool and smooth.

My dogs. The only named pair that mattered. A Mercy Street litter I’d split because the shelter begged me: please, separate siblings, they bond too tight, we need Sol to be fosterable. I’d done the paperwork with a guilt that made me brave and brought Luna home and went back for Sol a week later because brave isn’t the same thing as right.

My thumbs hovered. I typed This out of some childish loophole instinct and sent it.

At six I let the elevator cough me into the hallway and did the keys-and-dog chorus down the door like always. Sol’s bark was there, his nails like castanets on the floor. The living room had its plush tornado to testify. Half the toys were in the wrong half of the room because the good game is bringing the thing back and making me throw it again.

“Luna!” I called, already chastising those part of my brain that liked to get ahead of a worry. I did the whistle she responded to. I rattled the glass where I kept the treats. Sol ran tight circles.

The apartment answered with the kind of silence that looks like it’s listening. There was no door she could have opened, nothing to crawl under. The windows locked like tiny prisons. My bedroom closet was closed. The under-the-bed—nothing. The linen closet—only linen. The goddamn bathtub. The washer. The slab of space under the couch she liked when thunder came. The balcony, which would have required a ghost’s hands.

“Luna!” I called it different ways until the syllable got pilled with tears and wouldn’t swallow.

Sol whined. He brought me one of her toys, a frayed fox that squeaked in a broken, apologetic way. He set it on my shoe and looked up like a communicator from a species I had lost the translator to.

I called the super. Animal control. The microchip service. A vet tech friend who sounded kind until her voice started repeating the protocols and I heard the we in we always tell people to check behind the water heater and then hung up.

At ten, my phone buzzed without sound—I’d clicked the sound off again, a learned reflex that had already proved useless—and I watched the little white speech bubble on the lock screen like a syringe plunger coming down.

This or That?

Failure to choose immediately will result in a choice being made for you.

Mom or Dad?

There is a kind of quiet that happens around panic that makes you think you have time. It’s an artifact of adrenaline, the body pouring sugar into the engine and then asking the brain to please keep the car on the road. I read the text three times, each reading moving one component from joke to threat.

I did nothing.

It felt like virtue, that nothing. It felt like a stand. It wore the costume of I will not participate in your evil. Under that, it was a calculation: if something is done to me, it is not something I have done.

I called my parents. It rang and rang on my mother’s line and cut to voicemail; her voice said her name too fast, like she’d been embarrassed by the idea of having to record it. My father answered on the third ring, his phone voice already slightly irritated, the way ours always was with each other. “Yeah? What’s up, kiddo.” I hadn’t been kiddo in fifteen years.

“Where’s Mom?” I asked, stupidly, like she might be there next to him.

“What—” he started, and then: “She’s at her book thing. You okay? You sound—” He made an uncertain noise.

“Text me when you get to bed,” I said. “Please.”

“Is this a—should I be—”

“Just, please.”

That night, sleep was a body of water I walked into out of exhaustion instead of safety. I submerged immediately. I dreamed luna moths stuck to my arms like living paper decorations and tried to lift me by chewing tiny, patient semicircles out of my skin.

My phone lit the ceiling at 4:12 a.m. I didn’t have to look. I looked anyway.

Choice made.

By noon, my father’s voice was a sound I couldn’t clean off. “She must’ve… she went out back to water the basil. I took a call. Ten minutes, tops. The gate was shut. Her shoes—her shoes are by the door, I—there was a glass out there. Her glass. She just—”

A search party kicked the woods behind their development with bright sneakers and good intentions. The news was a rectangle of polite concern that ended with a smile about a local fair. The group texts got longer as the hope got smaller, a thing I’d never measured before. My phone vibrated until the metal innards felt warm. It never vibrated with what I wanted.

I told no one about the unknown number and its choices. Try shaping that story with your mouth and see how it feels in the air.

I told Sol that his sister was… I didn’t have a noun. Gone wasn’t right. (Gone) suggested an act. This felt like a verb had been stolen and the sentence didn’t care.

The apartment’s hairline cracks—the ones a landlord can ignore by painting over—turned into canyons. Into each I could fit the idea of a voice that had texted me and had not needed my phone to do it.

The next ping landed while I was halfway through a bottle that had not seemed like mine until it was half gone.

This or That? Spine or Skull?

I didn’t answer. The phone sat on the coffee table, screen going to sleep like a living thing entitled to it. The text notification stayed. Under the bedroom door, a softly persistent whispering began, like someone had put their mouth right against the crack and were telling the carpet a secret with great urgency.

I turned the TV up. The whispering twined around it the way ivy ignores fences. I stood, because standing is a tool when you have none. I walked to the door. The whispering was not words or it was and the part of me translating language had stepped back. It had the texture of words. The confidence. It was the sound of come here if the person saying it had learned to come here on another planet.

I didn’t open the door. I pressed my forehead to it and felt the cheap builder-grade hollow beneath the veneer and wondered if I did, finally, have a choice that was not pretend.

When I backed away, the phone’s light caught me again.

Failure to choose immediately will result in a choice being made for you.

“Go to hell,” I told it, which satisfied no one.

By morning, coffee was still not a thing, my mother’s picture sat on a Family Watch Facebook page surrounded by comments telling me where to look for a person who did not exist at the end of their advice, Luna remained a hole with fur around it, and my skin had a hum under it like I’d slept near a transformer. I called the number.

It rang.

It clicked.

The silence that answered was not background noise. It was a room with carpet and no one in it. I closed my eyes and adjusted so I could listen better, like that would change what I was hearing.

“Who is this?” I asked.

A breath, or the suggestion of one, in the way something hot suggests breath. Then a click. The line went to that polite kind of dead where the phone gives up trying to interpret.

Okay.

Fine.

If this was going to be a system, I could probe it like a fence.

I texted it first.

How do I win?

The dots—a thing I had not expected, hysteria that made my throat go cold—bubbled at the bottom of the screen and then stopped and then returned.

This or That?

Win or Lose?

“Cute,” I said to no one.

I typed Lose and watched, ridiculous, as if something might resolve in front of me like a magic eye poster. Nothing did. I waited. Nothing happened except, after a minute, the disorienting sensation that I had done something important I could not yet see.

I tried again.

This or That?

Question or Answer?

“Answer,” I said aloud as I typed it, because I am the sort of idiot who talks to text messages as if the program appreciates theater. The reply came instantly.

You have selected: Answer.

Suggestions: Keep your eyes open. Keep your phone charged. Keep choosing.

I threw the phone into the cushions like it had made a face at me.

The whispering under the bedroom door came back that night. It matched my breathing until my breathing matched it. I lay on the couch with the dog pressed into my calves like he was trying to become part of me and stared at the shadow underneath the door until it seemed to pulse independent of the light.

My sister, who had flown in to be near Dad, sent me a picture of Mom’s basil, blackening in its pot. I watered it. It’s still doing this. Is that a sign? lol I hate signs. I wrote no and stared at the three letters like I’d just successfully lied to someone for the first time and wanted to tell on myself.

At 3:03 a.m., the phone:

This or That? The Name You Use or The Name You Don’t?

I typed This again in the childish hope loopholes scale and smiled an ugly, desperate little smile at how clever I still could be inside a nightmare.

The next morning, the HR database at work called me Edwin instead of Ned. Every email addressed to me used the name on my birth certificate—the one my parents had ditched the second the nurse left the room and my face informed them No. At lunch I stood with my plastic tray in the cafeteria line and half of the people who’d known me for five years said Edwin like they’d been waiting for permission to do so and the other half watched me with the worry you reserve for people who have new symptoms.

I went into the bathroom and stared at my face and tried it. “Edwin,” I said, and my mouth felt inappropriate. I thought: what you choose disappears. But the inverse was happening, too. Something else came forward. As if erasing coffee made tea shine, selecting This made That the survivor. Picking Luna made Sol remain. Choosing Mom or Dad and failing—the coin toss took my mother and left the father who would wander his own house holding a glass he couldn’t remember emptying.

Okay. A rule. Rules are a mocking comfort, but a comfort. My brain loves rules. It once memorized the whole AP Stylebook instead of calling a girl back.

I called Priya.

“I know it’s late,” I said, and listened to her cough a laugh because I always started her calls that way. “But I need you to trace a number for me.”

She works for a carrier I’ll never name. She does things with phones that give her an expression like a god peeking between clouds and admitting he can, in fact, move a storm.

“My heart sank when I saw your name,” she said. “I thought you’d become one of those We need to talk people.”

“We do. But also, can you trace—”

“Give me the number,” she said. “And tell me it’s your boyfriend and not, like, a bot from Shenzhen in my fiber.”

“It’s a bot from… not here,” I said. “Just—give me something I can hang onto.”

She ran it while staying on the line, our small talk strapping itself to the sides of the minutes like paddles on a barrel. I answered questions about Dad that I didn’t want to. I said Mom’s name like it was a permission slip I hadn’t forged right. When she sucked in her breath, it sounded like a straw slurping the end of a milkshake.

“What?” My gut got ready to drop.

“This is going to sound… dumb,” she said. “But the originating switch says the call—the text—” She hesitated, reached for a word. “It’s—this number is yours.”

“Like spoofed?”

“No,” she said softly. “Like… the ingress is—” She made a helpless sound. “It’s zero. The caller location it gives me is… your coordinates.”

“My what?”

She read them. The numbers pinpricked a map in my head so accurately I smelled my hallway. “It says it’s coming from inside your apartment,” she said, and tacked on, like a good friend, “but that’s dumb, so it’s probably a glitch. Or a very bad joke. Or I need to recalibrate something. Send me a screenshot of the thread.”

I sent it. She went quiet. For a long time. “Is this a bit?” she asked finally, voice small.

“I wish it were,” I said.

Her typing sounds scratched in my ear. “Ned… your call logs show outgoing messages to this number. Your number. Like you are sending them to yourself. The IMSI—” She exhaled. “I don’t want to freak you out, but if I had to write down bananas impossible in a field labeled explanation, I’d do it.”

“Can you block it?” I asked. “From your side?”

She started to say No one can block— and reconsidered. “I can try,” she said. “But if this is—if this is a loop, my filter might just… catch the net and the fish at once.” She paused. “Are you okay?”

I looked at the bedroom door. The whisper had started up again, regular as a neighbor who plays scales on a clarinet every night at seven. “I’m—” I said, and then, honestly: “No.”

“Come stay with me,” she said. “Bring Sol.”

“What if it follows?” I asked, and listened to the way that sentence slid off the furniture of both our lives and into a space we didn’t have words for.

“If it follows, you won’t be alone,” she said.

The phone chimed.

This or That? Sight or Sound?

You have sixty seconds.

“Priya,” I said, “it’s doing the thing.”

“Put it on speaker,” she said, voice going professional in that way she had that made me breathe slower.

I did. Silence answered like a smile. The timer wasn’t on the screen—there was no countdown graphic to wring your hands at—just the knowledge that it was counting somewhere and the part of me that knows time in my bones could feel it.

“Don’t choose,” Priya said.

“It punishes that,” I whispered. Sol pressed harder into my shin. The bedroom whisper rose in volume to match my whisper, a petty thing that made my throat ache.

“Answer with something else,” she said. “Say neither. Say both.”

I typed Neither. Sent.

Invalid.

“Of course,” I said.

“Flip it,” she said quickly. “Ask it a question.”

I typed, hands shaking more from the adrenaline than fear. This or That? You or Me?

The dots appeared. Disappeared. Appeared.

This or That? Sight or Sound?

Thirty seconds.

“Okay,” I said. “It doesn’t like playing catch.” A laugh skittered out of me, brittle as candy glass.

“Choose sound,” Priya said, talking fast. “If you lose your hearing, you can still—”

“It’s never that literal,” I said. “It takes the thing you pick. It takes it like it never was.” I pictured a silence so thorough music had never been invented. I pictured a world full of people with mouths and hands and no words because sound was a rumor someone had debunked and everyone agreed to be relieved about.

“Choose sight,” she said, and when I sucked air, “Ned, if this is what you say it is, someone somewhere will remember that sound used to be a thing even if it’s gone. You remembered coffee. You remember Luna. It leaves you in a space where you can at least—” Her voice did not crack. Mine did, for her.

“Ten seconds,” I said, without needing the phone to tell me.

“Ned,” Priya said, and I thought of her small kitchen full of plants and how she labeled spice jars like she was leaving information to humans after the apocalypse, “choose sound.”

I typed Sound. I didn’t send it. The bedroom whispering surged, joyous, greedy. I erased Sound and typed Sight. I didn’t send it, either. The whispering changed pitch, like an orchestra tuning to a different A. This was not buying time. This was me deciding to either introduce the world to a new flavor of emptiness or make darkness the proper noun it has always wanted to be.

“Three,” Priya said.

I typed Sight. Every part of me lifted its hands to block the blow.

“Two,” Priya said.

The text box pulsed. My thumb hovered.

“One,” Priya said.

I didn’t tap.

Choice made.

The apartment didn’t shudder. The world didn’t invert colors. The TV didn’t hiccup. For two seconds, the silence had a sharpness to it like a knife right before it cuts a paper towel cleanly. Then Priya’s voice spoke a confused, distant hello in my ear and the whisper under the door was still there and my eyes still worked and the word music still had meaning and everything felt fine in the way a bridge feels fine to a person halfway across it.

“What happened?” Priya asked. “What did it take?”

A car honked outside my window. A siren rose and rounded a corner. Somewhere above me, someone dropped a pan and their roommate shouted something you can’t shout if your mouth has never learned the trick of tone. Sound still existed.

“I don’t know,” I said. My phone vibrated again.

You have selected: —.

Consequence applied.

This or That? Knees or Eyes?

“Don’t answer,” Priya said. “Come. Get in your car. Come now. I’ll trace—”

“Priya,” I said, and the door handle of my bedroom ticked like something testing patience. “It’s escalating.”

“When you get here,” she said, “I’ll put your phone in a Faraday bag. We’ll smash it. We’ll go to the carrier’s—”

“It doesn’t care about the phone,” I said. “It’s just using it to be polite.”

At my feet, Sol whined as if he could see the shape of the thing behind the door and wanted me to understand what big meant.

“Knees or eyes,” I said out loud, like writing it would make it less impossible.

“Ned,” Priya said, each syllable a rung on a ladder she wanted me to climb, “listen. There are rules. You found one. It prefers a choice. It punishes silence. It seems to scale. It is coming for you in a line that goes coffee, dog, mother, name. It will keep choosing things attached to you until it chooses you. Do you hear me?”

“I hear you,” I said, and the sentence knifed through the thick air like its own gallows humor.

“Then we change the rules,” she said. “We choose before it asks.”

I laughed helplessly. “What does that even—”

“Make a sacrifice,” she said. “Give it something you can stand to lose before it frames the question. Rip up pictures. Burn shirts. Throw your mugs away. Choose this or that yourself in your own house. Starve it. Don’t feed the pair. Don’t let it pair something you won’t break.”

“I can’t unpair my eyes from my knees,” I said.

“No,” she said, and then, softer: “But you can put something between you and it. You can make noise that isn’t music. You can cut the pairs it might offer while it’s thinking. You can—” She stopped. “And you can come. Bring Sol. If it can pick a lock it can pick a lock, but it will have to do it here, with me, and I will look it in the face and tell it no.”

The text pulsed.

This or That? Knees or Eyes?

Sixty seconds.

I did not sit. I did not think. I moved.

I grabbed Luna’s fox, Sol’s leash, my wallet, my mother’s basil—why?—and swept them into the bag that hung by the door. I yanked the charger out of the wall and shoved the phone in my pocket because even if the game didn’t need it, I did. I unlocked the deadbolt.

The whisper under the bedroom door grew excited, and because I am a human animal, I looked back.

I don’t recommend doing that if you are trying to be a person who leaves a place.

Something was pressing its face—its absence of a face—against the crack. If I said it was shadow, you’d think it was delicate, a negative space. This was shadow the way a storm cloud is solid when it wants to be. It had… shape. You know the wrong shape when you see it. It lifted the door handle delicately, the way you lift a thing you plan to break slowly. It knew my name, not the one HR had given me back, and it said it without breath. Not through wood—with wood, using the cheap hollow like a throat.

“Stop,” Priya said in my ear—not to me. To it.

I shut the apartment door behind me and went into the hall. I ran.

In the elevator, as the floors counted themselves down, my phone vibrated in my pocket like a heart. I didn’t take it out. I didn’t answer. The elevator dinged the way elevators have always dinged and I loved the sound like a person loves proof.

On the street, the wind knifed tears out of my eyes. I half-dragged, half-carried Sol to the car. I put him in the back seat with my bag. I put the basil there too. I slid into the driver’s seat and, like a man in a dream, yanked my seat belt until it clicked. The phone buzzed again, three short insistences. I started the car. The dash lit. The radio came on to a station that, for the first time, I imagined not existing.

When I pulled into traffic, the phone made a sound like a timer ending in a game you never get to win.

I looked.

Choice made.

“Which?” I whispered, as if it might answer, as if it wasn’t going to make me discover it the hard way. I checked my hands on the wheel. My knees flexed purposely under the dashboard on command. My eyes flicked to the mirror, to the road, to the light changing. Both were there. Both were mine.

The world’s edges felt… altered, the way things do when the air pressure changes and you don’t notice until your ears pop. I turned left toward the highway.

In the passenger seat, where no one sat, my phone lit with one more message, elegant as a chef’s plating.

You learn.

I learn.

This or That?

Me or You?

The steering wheel tried to climb out of my hands. The car behind me laid on its horn so hard I could feel the driver’s life in it. The light ahead swung stubbornly to yellow. I pressed the gas.

“Priya,” I said, “it’s asking—”

“Don’t say it out loud,” she said. “Don’t let it hear it in your mouth.”

I laughed, and it sounded like someone else laughing with my teeth. “It already knows.”

“It wanted you to run,” she said. “Good. Keep choosing where it can’t see you do it. Keep choosing things it can’t frame.”

I passed Lucci’s. Luca turned his sign from OPEN to CLOSED and, as if to prove I was still in a world that would humor me sometimes, flipped the light and put on a jacket.

“Green,” I said out loud, to no one, because the light turned green and it felt like there was a god left who would have me. “Green green green.”

The phone pulsed on the seat. Sol whined, low, uncertain. The city took a slow breath it didn’t know I was timing.

At the on-ramp, a billboard flickered with an ad that should have been for coffee and which, in this world, was an elegant photograph of steam rising from dark tea in a cup that made my throat feel like paper.

“Priya,” I said, turning the wheel, merging, choosing, “I’m coming.”

Behind me, my apartment building shouldered the sky. One window, third floor, left corner, pulsed—not with light, but with the feeling of someone standing at the glass.

The phone buzzed once and fell silent.

I did not answer.

I merged into the stream of headlights and taillights, the city making its self as it went along, and the on-ramp curved me into a choice I could pretend was mine.

—End of Part 1—

Part 2

I made it to Priya’s in nineteen minutes flat—record time, my skull buzzing like it had a second heart hidden in it.

Her building’s lobby smelled like cut limes and old heat. She was already at the front door, hair in a loose knot, keys in her fist like improvised brass knuckles. She didn’t say You look like hell but her face held the phrase. She crouched, rubbed Sol’s ears in a way that made his whole back end wag, then ushered us inside.

Her apartment was the opposite of mine—plants in every window, a shelf of labeled jars (coriander, cumin, star anise) that had the calm of someone who believes in categories. The TV was off. The speakers were unplugged. There was a silvered pouch on the coffee table: the Faraday bag she’d promised.

“Put it in there,” she said, palm open for the phone.

“It doesn’t care about the hardware,” I said.

“Humor me,” she said. “Let me do one thing they taught us in the manual before the world ended.”

I slid the phone into the pouch. The zipper’s teeth closed with the satisfying margin of a good decision. She stared at it like it might hatch. I looked at every other thing in the room because looking at the bag made the bag seem like a mouth.

“What did it ask, last?” she said.

“Me or You.”

Priya’s mouth made a line that looked legal. “Okay,” she said, the bright, controlled okay of a nurse with bad news. “So it’s doing the thing predators do when they’re bored of mice.”

She bent, hauled a milk crate out from under the coffee table, and started laying things on the rug: a handheld spectrum analyzer, a cheap RF sniffer, a little software-defined radio dongle like a toy. She thumped her laptop awake and her fingers flew. The screen bloomed with software I couldn’t read.

“If it’s riding the network,” she said, mostly to herself, “we’ll see it. If it’s riding the air, we might see it. If it’s riding you—” She stopped there because neither of us wanted to say then the best we can do is be loud when it bites.

The Faraday bag sat on the table like a lidded eye. No buzz. No ding. It made me uneasy, the quiet. I missed the terrible certainty of the chime.

“You said rules,” I said. “Name them.”

“It prefers a choice to be made,” she said, clicking, scanning. “It punishes indecision by making one for you. It escalates the stakes if you disobey. It targets pairs—literal pairs at first, then conceptual ones. It seems bound to your narrative—things sticky to you.” She glanced up. “Have you noticed it ask about anything I could choose?”

“No,” I said, and we both clocked that as both observation and omen.

“Then there’s a scope,” she said. “That’s something.”

“And it learns,” I said. “It said as much. You learn, I learn. It closed my loopholes.”

She nodded, eyes on the waterfall of RF noise sliding down her screen. “Then we have to open a hole it doesn’t expect. We have to pair it to something it can’t consume without losing its teeth.”

“Like what?”

“Like itself,” she said.

I laughed in a way that made Sol’s ears tilt. “It doesn’t answer my questions.”

“No,” she said. “But it traces to you. And we have two yous.” She tapped the Faraday bag. “Your phone, your line. And—” She held up her own phone like a magician revealing a duplicate flower. “Me.”

“You can’t be me,” I said, and heard how childish it sounded the second it left my mouth.

“I can be whatever the network lets me be,” she said. “For a minute. If I mirror your SIM, create a shadow line, then for one granular moment the world contains two of you. If it asks Me or You, and it can’t tell which is which—maybe it eats its own tail. Or chokes.”

“You can’t just—”

She raised an eyebrow. “Watch me.”

She moved like she was playing an instrument—the good kind of confidence that makes the people in the cheap seats relax. She pulled a tiny kit out from the crate, the sort of thing only someone who loves their job and hates their employer’s limits would own. She popped the SIM tray from my phone, slid the wafer-thin card into a reader, then fed its soul into her laptop.

“Are we committing crimes?” I asked.

“Only the good kind,” she said.

The RF sniffer burped. She frowned. “Huh.”

“What?”

“It’s quiet,” she said. “Like… quieter than my apartment has ever been. As if something is holding its breath.” She flicked a switch, the analyzer hummed. A faint spike drifted in the noise. “There,” she whispered. “On and off. A whisper of whisper. Your bedroom door, in spectrum.”

The Faraday bag sat like a calm pet. She copied, wrote, burned the mirror to a second card. She held it in the air and looked at me like changing your name at the courthouse. “This makes me a ghost of you,” she said. “Just for a minute. If that number texts, both of us will get it.”

“And then what?”

“And then we answer at the same time with different choices,” she said. “We force it into a superposition. If it’s as clean and brittle as it sounds, it might—” She flicked her fingers, a motion like a brittle leaf breaking.

“And if it chooses one of us to punish for being clever?”

Her eyes didn’t blink. “Then it will choose you,” she said. “If I’m bait, I’m bad bait. I’m not part of its diet—yet.”

Yet.

“Priya—”

“You asked me to help.” She slid the ghost SIM into a mottled old Android she kept for testing. “This is me helping.”

She texted from my ghost number to my real number.

This or That?

Us or Them?

I snorted. “That’s not how—”

Her phone buzzed. The Faraday bag thrummed on the table like a live thing. The laptop pinged—some log accepting some registration.

On the testing Android: my own thread mirrored back—everything the unknown number had sent me, sitting there like a duplicate diary. The newest message arrived on both screens in the same instant, perfectly synchronized.

This or That? Me or You?

There it was again, elegant, indifferent. Beneath it, the polite lie of typing… in three dots on both phones.

Priya lifted the testing phone so the two screens faced each other like two knives glinting.

“On three,” she said. “We split it.”

“What do we pick?”

“You say Me,” she said. “I’ll say You.”

“Won’t that just make it easier?”

“If there’s a brain behind this, it wants a clean world. Let’s give it two conflicting edges. Let’s make it decide if it can tell which one of us counts as you.” Her thumb hovered. “One.”

“Priya—”

“Two.”

“Wait.”

“Three.”

I typed Me and hit send. Across from me, on the ghost, she typed You and sent. The room held its breath. For a half-second nothing happened and hope rose in my throat like a stupid balloon.

Then both screens replied in the exact same white:

You have selected: Me.

Consequence applied.

The Faraday bag shuddered. The lights in Priya’s kitchen flickered so minutely you could call it imagination, if you needed to stay happy. The RF plot stuttered, then climbed, then steadied again, an animal shaking something off.

“Which of us was Me?” Priya asked.

My mouth went dry. “I… I don’t know.”

“What did it take?” she said. “Check.”

I ran my hands over myself like a man discovering he’s still in one piece. Knees bent. Eyes saw. The cockroach‑stubborn little part of the brain that inventories loss came up blank.

My phone buzzed in the bag. I fumbled the zipper. Another message.

Learning complete.

This or That? Knees or Eyes?

“Shit,” Priya whispered. “It didn’t choke.”

“No,” I said. I stared at the words until they moved like water. “It cleared its throat.”

I put the phone down like it might bite. “What if it’s trying to get me to choose something I can’t live without so I stop being a moving target?” I said. “What if it wants me still?”

“It already wants you still,” Priya said. No sugar. “So we decide what stillness is to you.”

The text pulsed. Sixty seconds arrived without being announced. The ceiling seemed lower.

“Decoy,” Priya said, moving. “We build decoys. It goes after what is paired to you—we unpair, we deliberate misname. You don’t get to be you in the house. You don’t get to be the center.” She swept her hand—there was a force to it, cult-leader, general. “Label everything. Break everything. Put a hat on the dog and call him Carpet. Eat tea with a fork. Move the bed into the kitchen. You are going to be insufferable to live with for a night.”

The laugh forced itself out of me. “I can’t outrun it with whimsy.”

“You can buy time,” she said. “And we need that minute.”

She grabbed a Sharpie, wrote FRIDGE on the oven, OVEN on the fridge. She took a post‑it and smacked WINDOW across the clock. She handed me the pen. I wrote ME on the basil plant and YOU on the lamp and hated myself for how good it felt to make a mess that wasn’t the world’s.

Knees or eyes. Knees or eyes.

My mouth was dry. Sol stood strange, not sure if this was a game where he knew the rule. He leaned against me and I felt the insistence of his living weight.

Priya stepped close enough that I could see the freckles on her right cheek, the one hidden most days under confidence. “Pick,” she said.

“I can’t,” I said.

“You have to,” she said.

“What if I choose Me,” I said, the worse thought blooming, “and it stops?”

“Ned,” she said, so gently I felt the name slide into my body and sit there. “If that is the rule… you know the math.”

I thought of Luna missing. I thought of my father standing on the back step with the basil pot and the hose and the way he would look at the line where the patio met the lawn like he was waiting for a mother-of-pearl shell to be set there with a note inside. I thought of my mother’s voice on her voicemail and how it would be like a movie prop if she never recorded another. I thought of coffee—how stupid—and the mug I hated because it had betrayed me. I thought of being a person in a world that didn’t have to be explained, each object making room for the next.

“Ten seconds,” I said, because you can feel a minute die in your bones. Priya’s eyes shone, the way eyes do when they’re still holding their water like a talented dam.

“Choose,” she said.

“Knees,” I said—maybe, because maybe I could crawl into a life and call it a life, maybe, because maybe what passing itself off as a god wanted most was to make me choose to not see.

I typed Knees and hit send. The room didn’t skew. My legs didn’t give out. For a second I wondered if I’d gamed it, if Knees meant something like wobble in a dialect I didn’t share with angels.

And then I looked at the photo strip on Priya’s fridge—really the oven now—that held us both in a three-frame laughter at a street fair last summer and realized I could not remember walking. I knew that I had done it. I had gotten from place to place, my body had performed the miracle. But in my head, every memory that had had walking attached now glided. The pool of water where I’d learned to step without fear? It became a distance I covered. The time I’d hiked Devil’s Backbone with my sister became a series of pictures without the click of footfalls. The itch of wanting to run when delayed sprouted and died without a verb to feed it.

My knees bent. They worked fine. But the story of them was gone.

“It’s taking narratives,” I said, breathless. “It’s thinning the film.”

Priya nodded once, a hard motion. “Then the only thing it can’t survive is the end of your story.”

She went to the table, picked up my phone. She placed it in my hand. The screen lit obediently. It buzzed again.

This or That? Me or You?

We both laughed, the unfunny laugh of a person who’s found the bottom they kept imagining.

“You know what happens if you choose You,” she said.

“It could be anyone,” I said. “It could be you. It could be everyone. The world makes a shape around pronouns.”

“And if you choose Me…” She didn’t finish. She did not have to.

I looked at the Faraday bag. I looked at Sol. He had Luna’s fox in his mouth—the toy he’d carried around the apartment like an icon.

“What if I make Me and You the same thing,” I said. The last of the hubristic problem-solver in me delivered it with a flourish.

“How,” she said, not with mockery, but with a real opening.

I opened my contacts. I edited Me. I changed it to You. I opened a new group thread and named it WE and added my number twice—real and ghost—and Priya’s once. The thread chirped like a bird agreeing to be an omen.

“This is magical thinking,” I said. “But all of this is.”

She smiled without humor. “Then do magic.”

I typed into WE with my real number:

This or That? Me or You?

Both phones vibrated at once. The unknown number answered inside the group as if it had been waiting in the doorway and finally been invited to step in.

This or That? Me or You?

The message appeared twice—the same message, mirrored. The name on my line wore my contact’s label. You asked Me or You? in WE.

I typed Me on my real line. On the ghost in Priya’s hand, she typed You. We hit send in the same breath.

You have selected: Me.

Consequence applied.

Thread ARCHIVED.

The word archived carried more weight than it deserved. The screens went gray in that thread, like a curtain whisked down. The Faraday bag gave one small kick and then lay still.

In my hand, the phone buzzed one more time, just once, like someone knocking gently to see if I was up.

“Ned,” Priya said.

I looked at her, and for a second saw the frames—the small frames that make a life—that would not have existed if I had not met her: the way she labels flour FLOUR and sugar SUGAR even though no one else needs it. The way she says oof when she sits down and immediately makes fun of herself for saying oof. The way she says my name like it’s not the only thing about me.

The room slid sideways; not the world—the center of it. A soft pressure against my chest, like a doorbell rung from inside. I felt the outline of Myself, the one the game had been pushing me into, the one the rules prefer, begin to refine.

“Wait,” Priya said, and stepped toward me on legs that, in my head, were now a beautiful blur.

“It wanted a clean world,” I said. “Let’s give it one.”

I kissed her forehead, because the part of me that was all stupid movie endings needed to. She smelled like coriander and solder. Her hands closed around my wrists and then—nothing as dramatic as gone. None of the flares of white I’d prepared for.

Just… less.

The exact amount less a person becomes when his story stops being told by his own body.

It was not pain. It was deletion. Not the violent kind; the respectful kind; the kind where the actor leaves through a door the set has always had and the audience sits a second longer than the script plans because they are adjusting to the absence of footfalls.

The last thing I heard (and I was grateful I still had that) was Priya saying my name through her teeth like it was a rope.

I am not in the rest of this story.

What you get now is Priya’s voice, because this is what good engineers do when systems fail: they write reports so the next person can build the right thing.

Coffee is back, first of all. That’s the thing everyone asks when I tell them the short version and then pause long enough for them to make a joke. The next morning I walked into Lucci’s and Luca did a little awkward flourish with the espresso handle like he’d been practicing cartwheels in a phone booth all night. “The usual?” he said, and then flushed like he’d gotten away with a swear.

Sol barked when I carried two coffees back onto our block. He was holding Luna’s fox, still, like a dumb child with a job. He slept on the couch that night and made dog‑dream noises. In the morning I opened the door and there was Luna on the mat like a person trying to understand a magic trick. She didn’t smell like the street. She didn’t stink of creek. She just wagged all over and Sol made the sound dogs make when a toy they thought was broken squeaks again. I cried into their collars until they both tried to lick my eyeballs.

The unknown number stopped. That’s the second thing people want to know. No more This or That. The Faraday bag sits in the drawer with the spare batteries and the tape that refuses to stay in its own roll. Sometimes I open the drawer and stare at it the way a person stares at a snake’s shed skin. You could still lift it and pretend the snake.

Ned’s phone is in there too.

His father calls me. Not every day. Enough. We talk about basil. We talk about rain. We do not talk about the minute between sixty and zero. There is a gap where his wife used to be and I cannot fill it, and he does not ask me to. Once he said, “I keep thinking I can almost remember something and then there’s just a good breeze,” and I said, “I know,” and he said, “Do you?” and I said, “Yes,” and neither of us tried to prove it.

His sister came over with a grocery store cake and an apology she didn’t owe me, and we cut the cake and ate it with forks standing up in the kitchen because the dogs were insane over the sugar. We did not light candles. We said his name like a promise and a password. In this version of the world, the obituary didn’t have to be printed. I kept the one we would have written in a locked file named README.md like a nerd’s prayer.

On my laptop there’s a folder of captures from the night—the RF plots, the timestamps, the way the ghost SIM registered and then deregistered itself like a polite intruder. Every so often I open it and go through it frame by frame as if one of them might blink and show me his outline. That’s not how data works. I do it anyway.

I took the group thread called WE and pinned it. It’s gray now, archived, like a plaque on a park bench. Sometimes, when the apartment is too quiet, I open it and look at the conversation that closed itself like a book. You have selected: Me. It reads like a polite suicide note written by a machine that believes in good grammar.

The basil lives on my sill. It is thriving, idiotically. I have to pinch it back so it won’t bolt in this ridiculous light. On the pot I wrote ME in Sharpie and then, because I am sentimental in ways I will only admit in black ink, I put a second label under it that says YOU.

A week after, I got a text from an unknown number. My stomach dropped with the kind of practiced fear the body loves. I opened it in the dark and let the light paint my face.

Ping test. You there?

It was from our own test bench at work, the one that pings endpoints to make sure the baby network we’re building hasn’t tipped its bowl. It had never texted me personally before, and I took the future I believe in by the shoulders and shook it until it did.

“Yeah,” I wrote back, and then, because I am trying to train the universe like a cat, I added: “We.”

The phone didn’t reply, obviously. It’s a machine. It isn’t the same thing that asked Ned to break himself into a clean line. But the next morning, as I stood in Lucci’s and Luca poured coffee into two to‑go cups and Sol and Luna tangled their leashes in ecstatic, obtuse geometry, the radio played a song so old it had worn grooves in my neurons. The singer held a note like a dare. A woman at the window laughed and the laugh had all its pieces in it. A kid dropped a muffin and cried in a register so high Luca’s lights almost tried to go out.

I took both cups home. I set one on the counter next to the stove I’d labeled FRIDGE and left it there, not as a ritual, but as a habit I refuse to break. The dogs bumped my knees and I bent down to press my forehead to theirs, and in my head I could remember walking again because sometimes the brain does you favors when you aren’t looking.

In the evening I sat on the couch with both dogs making the couch into a terrain feature and opened the wedding album Ned had never had a chance to put away because there hadn’t been one. That’s not grief. That’s just grammar. We didn’t do that. But I opened a photo from the fair anyway—me and him and stupid fried dough and powdered sugar wearing our black shirts like we were in a band called This or That. I took a pen and on the back I wrote YES.

If you want the kind of ending you can hand to someone at a party and have them smile politely, take this: the number stopped; the dog came back; the coffee returned; the world left its drawers open and then closed them again.

If you want the kind of ending the truth gives you, take this instead: a person put a word in the place the world asked for one and the world took it. He left behind a direction—choose for each other when you have to—and a practice: when asked to make the world smaller, make it bigger by one person.

Sometimes, when I turn off the lights, the apartment pricks my skin with the memory of a whispering that isn’t there. In those moments I say his name and then mine as if reciting This and That in a language that declines in plurals. I don’t wait for a reply. I know how systems terminate. But I’ve learned something from all this that the manuals never told me: some choices you make by yourself in the dark aren’t really for you at all, and the proof is that other people can see them in the morning.

The last thing on my whiteboard at work, written in Ned’s handwriting from a sticky note he left near my laptop the week we met, says this:

Keep your eyes open. Keep your phone charged. Keep choosing.

I leave it up. Not because the thing that asked for Me or You is still listening. Because I am.

Because we are.

END!

News

A Local Man Was Found Dead Yesterday. It’s My Fault.

Part 1 I needed to go for a walk that day. It didn’t matter that I’d been exhausted the day…

My mother used to tell me that my father was an angel. I thought she was crazy until I saw him myself

Part 1 I don’t remember my mother ever being sane. From the day I was born, the house made a…

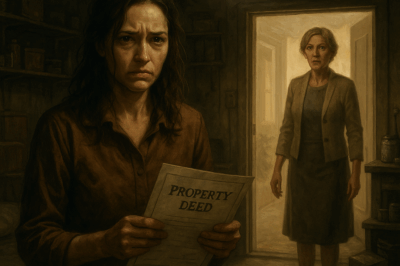

Stepmom Made Me Sleep in the Garage for 4 Years—Then Tried to Steal My “Dead” Dad’s Estate

Part 1 She thought she was playing a long game. She never realized I was silently keeping score. I’m Stephanie,…

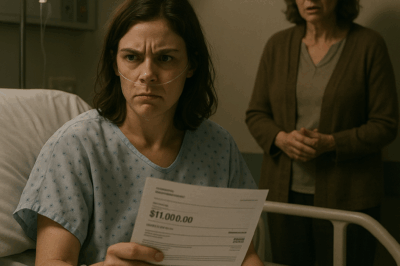

My Mom Took $11K While I Was in Surgery and Said It Was “For Family”

Part 1 Okay, here’s how it really started. Not with a bang, but with a rectangle of paper taped to…

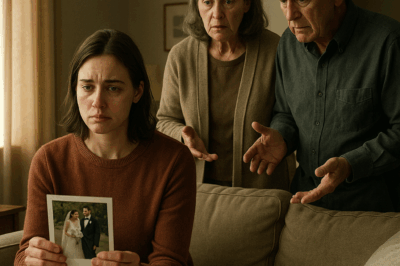

Parents Funded Brother’s Lavish Wedding, Then Begged Me For Help Years Later

Part 1 The courthouse steps felt cold under my bare legs that morning. I’d chosen a simple cream dress—nothing fancy,…

My wife has started dreaming about things I’ve done

Part 1 “You left the utensil drawer open this morning, didn’t you?” she asked, stepping out of our bedroom as…

End of content

No more pages to load