I Identified My Father’s Body in 2005 — But Last Month, He Called Me, “Little Star… It’s Me.”

Twenty years ago, I buried my father — a decorated Navy SEAL who died in a classified mission off the Virginia coast.

I was the one who identified his body. I folded his flag. I thought that chapter of my life was over.

Then, last month, my phone rang at 2:07 a.m.

A man’s voice — rough, hesitant, and heartbreakingly familiar — said,

“Little Star… it’s me.”

I froze. Because that was his nickname for me.

Part 1

The night my father called me, the landline rang.

Not my cell. Not a text. The actual plastic phone mounted on the wall beside my fridge, the one I kept around out of habit and storms and the vague idea that old numbers might still remember how to find me.

It was 2:07 a.m. The kitchen was dark except for the little orange light on the stove clock. I’d just poured my first cup of coffee, because sleep and I had been on a break for years, and the sound of that ring—sharp, metallic, old-fashioned—cut through the quiet like something out of a movie.

Nobody calls after midnight with good news. That’s a rule the universe respects.

I almost didn’t answer. Then I saw the caller ID.

My hand froze around the mug.

Norfolk, Virginia. The old code that used to flash on every deployment call, every holiday greeting from “down at the pier,” every Sunday afternoon check-in after my dad’s second tour. I hadn’t seen that number in twenty years.

In twenty years, I had gotten very good at telling myself stories.

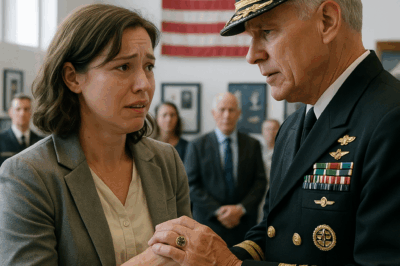

My father, Commander Robert Henderson, U.S. Navy SEAL, died in 2005 when I was twenty-five. A classified maritime test off the coast of Virginia. An explosion. Fire. Signal lost. The words in the letter blurred together when the officer read them to me, but the bullet points stayed.

Presumed killed in action.

No remains recovered.

I stood beside the flag-draped coffin anyway. Folded the triangle of colors with my own shaking hands. Placed a white rose on the smooth wood because that’s what daughters do. They told me the body was too damaged for viewing. I accepted their word as fate and tried to teach my heart to do the same.

The landline kept ringing.

By the fourth ring, I’d set the coffee down, wiped my suddenly damp hand on my pajama pants, and reached for the receiver.

“Hello?” My voice sounded thin in the dark.

For a moment there was nothing. Just static, that low spherical sound you hear when you press a shell to your ear as a kid and someone tells you it’s the ocean.

“Hello?” I tried again. “Who is this?”

A man’s voice broke through, rough and uncertain. Older. Worn.

“Little Star,” he said. “It’s me.”

The mug slipped from my hand and shattered on the tile. Hot coffee splashed across my bare feet; I didn’t feel a thing. My knees hit the cabinet with a thud that would leave a bruise in the morning.

“Who is this?” I whispered.

Static hissed, rising like a wave.

Then the line went dead.

The kitchen went very, very quiet. No hum of the refrigerator, no drip from the faucet. Just my own heartbeat hammering in my ears and the dial tone buzzing like a flatline.

I stared at the receiver as if it might bite me.

Little Star.

Nobody called me that except my father.

He’d given me the nickname when I was five and terrified of the dark. He’d stuck glow-in-the-dark stickers to my bedroom ceiling in the shape of a crooked constellation and whispered, “That’s us, kiddo. Every time you get scared, look up. You’re my little star. You don’t disappear just because it’s night.”

It was the last thing he said to me before his final mission, standing outside the gate with his duffel over his shoulder. “Keep shining, Little Star,” he’d teased. “I’ll find you in the sky.”

He did not come back.

Now, twenty years and a whole lifetime later, his voice had reached across state lines and whatever divides the living from the dead and said the one thing that could rip every scar I’d grown right open.

It’s me.

By 2:30, the shards of the coffee mug were still scattered across the floor and I was sitting at the kitchen table in my robe, wrapped in the stale light of the stove hood like a bad photograph. My hands were shaking so hard I had to lace my fingers together to keep them still.

The voicemail light on the base unit blinked red.

One message.

I swallowed, reached over, and pressed play.

Static. Again that hum, like wind across a microphone.

“Little Star,” the voice said. “It’s me. I just figured out who I am.”

Click. End of message.

I played it three more times. Five. Ten. Every repetition made it worse. The timbre was right. The slight rasp in the back of the throat from too many cigars in the late ’90s. The way he clipped the “t” in “it’s” and stretched the “me” just enough to sound like reassurance.

If it was a prank, it was a cruel one. Someone would have needed recordings, details, an ear for cadence. The thought of some stranger leaning over a microphone and imitating my dead father made nausea claw up my throat.

But if it wasn’t a prank—

I stood abruptly and went to the pantry, climbing up on a chair to reach the top shelf. Behind the hurricane candles and the emergency radio sat an old cedar box, the brass latch worn smooth.

I brought it to the table like an offering and opened it.

Dog tags. His. The chain polished by my thumb over years of nervous fidgeting.

A stack of letters, the paper thin and soft from my re-reading. Commendations with embossed seals I stopped showing people after the casseroles stopped arriving that first year. A pocketknife with a chipped handle he’d carried since Panama.

And a photo.

He was forty-five in that picture, standing on the deck of a ship in his dress blues, sun glinting off his silvering hair. Serious, but smiling in that way he had when my mother took pictures—half cooperative, half embarrassed.

I held the photo up next to the phone, as if the pixels on the caller ID display could line up with his face and make the world make sense.

“Dad,” I said to the empty room, feeling ridiculous.

Nothing answered.

On the last letter in the stack, his handwriting leaned more than usual, as if he’d been writing in a hurry. August 2004.

If anything ever happens to me, Little Star, promise me one thing. Don’t stop asking questions. The truth’s a stubborn thing. Hides in plain sight and waits for the right eyes.

I’d always chalked that up to his general life philosophy. “Question everything,” he used to joke. “Especially the people in uniforms.”

Now it felt like instructions.

By the time the sun pushed gray light through my kitchen window, my decision was made. I grabbed my keys, shoved on yesterday’s jeans, and headed for the car.

If my father was dead, someone had just used his voice to hurt me.

If he wasn’t, then in 2005 I had buried the wrong man.

Part 2

The Department of Veterans Affairs office in Augusta opens at nine. I was in their parking lot at 8:38, eyes gritty, hands jittery from no sleep and too much coffee.

Inside, the fluorescent lights hummed and the air smelled faintly of burned coffee and toner. A handful of veterans sat in plastic chairs along the wall, staring at their phones or the floor. The clerk behind the counter looked barely older than the students I taught at the community college—close-cropped hair, neat shirt, expression set in that professional “How can I help you?” line.

“I need to talk to someone about my father,” I said.

“Okay,” he replied, fingers hovering over his keyboard. “Name?”

“Commander Robert Henderson,” I said. “Navy. SEAL. Reported killed in action in 2005, off Norfolk.”

He typed, squinted at the screen. “Yes, ma’am. I’ve got him here. Status: deceased. Service-connected—”

“He called me last night.”

The words felt absurd as they left my mouth. A couple of men in the waiting area glanced up.

The clerk blinked. “Excuse me?”

“I got a phone call from my father’s old Norfolk number at 2:07 a.m.,” I said. “I picked up. I have a voicemail. It’s his voice. He said my nickname, he knew details—this isn’t a wrong number. Something is wrong with your records or with—” I stopped. I wasn’t even sure where the sentence was headed.

His face shifted—not to disbelief, exactly, but to a kind of careful compassion, the look you give someone standing a little too close to the edge.

“Sometimes,” he began, “families receive scam calls from people claiming—”

“This isn’t a scam,” I snapped.

Silence pressed against the institutional beige walls. I forced myself to lower my voice.

“Look,” I said. “I know how it sounds. But my father was on a classified op. We never saw a body. The report was vague. If there are any… anomalies, missing records, anything… I need to know.”

He hesitated, then tapped a few keys, frowning at the screen.

“Ma’am, the file is sealed under a Defense secrecy provision,” he said. “Operations involving special warfare units from that period are… above my pay grade.”

“So that’s it?” I asked. “I just go home and wait for the 2 a.m. phone calls to stop?”

He chewed his lip, then reached under the counter and pulled out a form.

“If you believe you’ve been contacted by an active, missing, or misidentified service member,” he said, reading off the top, “you can fill out a contact incident report. It gets forwarded to Norfolk command. They review it, compare with any open investigations. Sometimes it’s nothing. Sometimes it… isn’t.”

Paper. Another form in a system built out of forms and folded flags.

I took the clipboard and filled in every box. Name. Rank. Date of “death.” Time and date of call. Exact wording of the message. I attached my cell number, my email, my physical address, the dog’s name—anything that might pin me down as real.

The clerk took the form back, scanned it into the computer, and said, “We’ll be in touch.”

I walked out into the brittle morning cold and stood on the sidewalk for a minute, stomach hollow. The VA building squatted behind me, brick and glass and bureaucracy. Somewhere in there was a file with my father’s name stamped across it, tucked away like he was a finished chapter.

My phone buzzed in my pocket.

For a wild second, I thought: He’s calling back.

It wasn’t him.

It was a Florida number I didn’t recognize and an email from Cole Martinez, both pinging in at the same moment.

Cole had served with my dad for a decade. When I was a kid, he was “Uncle Cole,” the guy who’d bring me plastic submarines from wherever he’d been and teach me how to tie knots my mom wished I didn’t know.

I hadn’t spoken to him in eight years.

I called him first.

He picked up on the second ring. Background noise—waves, maybe, or just wind.

“Hello?”

“Cole, it’s Clare.”

“Clare Bear,” he said automatically, then cleared his throat. “Sorry. Force of habit. How are you, kiddo?”

“Forty-five,” I said. “Not much of a kid anymore.”

“You’ll always be the one trying to climb the pier rail while your old man yelled at you to keep your damn life jacket on,” he replied. “What’s going on?”

I leaned against my car, suddenly glad for the cold seeping through my coat.

“I got a call last night,” I said. “From 757. Norfolk. Landline. It was Dad’s voice. I have a voicemail.”

He didn’t laugh. He didn’t tell me to see someone. There was a sharp inhale, a rustle, like he’d sat up.

“Tell me exactly what he said.”

“‘Little Star, it’s me. I just figured out who I am.’” My throat tightened around the words.

He was quiet for a beat.

“You still have his personnel packet?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “In a box. Why?”

“Open it tonight. Look at the after-action summary from Iron Wave. Check the sign-off. Whose name is on it?”

“I’ve read it a hundred times,” I said. “Captain D. Reynolds.”

“Yeah,” he said grimly. “Reynolds wasn’t Navy. He was private security—contractor. The whole op was a Frankenstein. SEALs plus some experimental tech plus a bunch of civilian cowboys who thought they were invincible.”

“I don’t understand,” I said. “They told us it was a routine test gone wrong. Explosion, structural failure, no survivors.”

“They told you the sanitized version,” he said. “We all got the same story. Downrange, though? Rumor mill said something different. That the mission got yanked off the books halfway through. Black budget, black site, black hole. If there was one thing your father hated, it was when people used his men as lab rats.”

The asphalt felt unsteady under my boots.

“Are you telling me he survived?” I asked.

“I’m telling you there were holes,” Cole said. “No recovered body. Identification based on… let’s call it ‘best guess.’ And now you’ve got a voice from Norfolk twenty years later using a nickname only he ever used. If it is him…? Then someone made a choice to lose him on purpose.”

I slid into the driver’s seat and shut the door, the sound of it a little too loud.

“He wrote me once,” I said, “before Iron Wave. Said if anything ever happened, I shouldn’t stop asking questions.”

“Then honor that,” Cole replied. “But be careful who you ask.”

“Who would know more than you?” I said.

“Officially?” he said. “No one. Unofficially…” He paused. “There’s a guy. Colonel Michael Reeves. Defense Investigations. Retired now. He was the one they brought in after Iron Wave blew up. Literally and politically. He’s the kind who grew a conscience instead of a pension. I’ll text you what I’ve got.”

“Cole?”

“Yeah?”

“If this turns out to be nothing—if it’s some scam…” I swallowed. “I’m not sure I can lose him twice.”

He was quiet for a long moment.

“Listen to me, Clare,” he said. “You’re not crazy. Whatever this is, there’s a reason that phone rang. If your old man could find his way back from whatever they did to him, it’d be because he’s too stubborn to stay dead.”

Despite everything, a ghost of a laugh escaped me.

“I’ll call you,” I said. “When I know more.”

I hung up and drove home on autopilot, the Maine pines blurring past. When I got there, I pulled the cedar box back onto the table and dug out the manila folder marked IRON WAVE – 2005.

The mission summary was four pages long and somehow said nothing.

Test of experimental underwater comms array. Location classified. Vessel: classified. Team: five SEAL operators, three contractors. Incident: sudden explosion. Damage: catastrophic. Presumed cause: equipment malfunction. Casualties: five presumed KIA. Recovered: partial remains, dog tags.

Sign-off: Capt. D. Reynolds, Contracting Oversight.

Cole was right. The only name at the bottom belonged to a man who’d never taken an oath in front of a flag.

I flipped to the back. There was a receipt list of “personal effects: recovered, returned to NOK.”

Dog tags. Pocketknife. Compass.

Items more intact than a body, apparently.

The email from Florida was still unread in my inbox. I opened my laptop.

A link from a local Jacksonville blog blinked up at me. “Unidentified Veteran Found Near Shipyard: ‘I Used To Be Somebody.’”

The grainy photo showed a man in his late fifties or early sixties, sitting on a curb outside a clinic. Weathered face, gray stubble, hospital bracelet. There was a look in his eyes I recognized too well—a mixture of confusion and stubbornness.

The article was three months old.

Miss Lorraine Harris, director of Harbor House, said the man had been staying at their shelter off and on for a few years, using different last names and claiming he’d served “in the Teams.” Medical staff reported signs of head trauma and memory loss. The man reportedly said, “I think I used to be important. I just can’t remember who I was.”

The author made it sound like a curiosity. A human-interest footnote between football scores and weather.

My cursor hovered over the photo.

The build. The region. The timing. And that phrase.

I just figured out who I am.

I printed the article and stuck it in the folder with Iron Wave.

Then I grabbed my keys again.

In the driveway, the sky over Maine was iron gray, clouds stacked on the horizon. The brass compass Dad had given me when I was ten sat in the cup holder, its needle jittering like it was nervous too.

He’d pressed it into my hand at some roadside gift shop, smelling like jet fuel and sea air and cheap coffee.

“So you can always find your way home, Little Star,” he’d said.

Home wasn’t a place right now. It was a voice through static and twenty years of missing pages.

I pointed the car south.

Part 3

The road out of Maine is straight and narrow and old, lined with pines and clapboard houses and signs for lobster shacks that only open in July. I’d driven it a hundred times in my twenties, down to Boston for concerts, further to see my ex-husband’s family in Connecticut.

I’d never done it with a ghost riding shotgun.

By the time I hit the New Hampshire border, the sky was softening from slate to blush. My phone sat silent in the passenger seat, screen dark. I’d turned off the radio, not wanting other voices. Every few miles I’d tap the voicemail icon, press play, and listen to that seven-second fragment.

“Little Star, it’s me. I just figured out who I am.”

Sometimes it sounded completely like him. Other times, it felt like I was forcing the match, like my memory was putting his face over some stranger’s words.

Grief does strange things. It rearranges your sense of time. It makes you see loved ones in every passing silhouette for years afterward. I’d spent entire afternoons in grocery stores once, following some poor man in a navy jacket down the aisles because his shoulders reminded me of Dad’s from the back.

This was different. This was a voice that knew my name, my nickname, the pattern of affection and apology my father used whenever he’d missed a birthday or a recital because Uncle Sam had a schedule.

Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York blurred past. Somewhere in New Jersey, a semi-truck blasted its horn as it passed me; I hadn’t realized I’d drifted five miles under the speed limit, staring at nothing.

Dad had always loved road trips.

“The road’s honest,” he’d say, hands at ten and two, eyes scanning the line where asphalt met horizon. “You find out who you really are when it’s just you, four wheels, and too much thinking time. You can pretend you’re running, or you can admit you’re chasing.”

Right then, I didn’t know which one I was doing.

Norfolk, Virginia, greeted me with the same smell it had twenty years before—salt, diesel, and something metallic underneath. The cranes at the shipyard rose out of the dusk like skeletons. The motel I picked had a flickering neon sign and a door that stuck.

It felt appropriate.

I slept for four hours, if you can call it sleep. Every time I closed my eyes, I saw caskets and cold metal rooms and my father’s face half in shadow.

At nine on the dot, I walked into the Norfolk VA Regional Office with a copy of my father’s death certificate in one hand and the Jacksonville article in the other.

The clerk at the front desk—a woman in her early fifties with gray-streaked hair pulled into a bun—took my ID and typed, nodding to herself.

“Commander Henderson. Deceased, two thousand five,” she read.

“Everyone keeps telling me that,” I said. “But I got a phone call from his old base code last week and there’s a man in Jacksonville who looks like…” I forced myself to stop and breathe. “Look, I don’t need a lecture; I need someone who knows what Operation Iron Wave really was.”

The woman’s eyes flicked up from the monitor, assessing. Less pity than the clerk in Maine. More… curiosity.

“Those records are sealed,” she said. “Special operations from that period are on a need-to-know basis only.”

“I’m his daughter,” I replied. “If someone misidentified my father’s body and dumped him in the wind for twenty years, I need to know.”

The corner of her mouth twitched, like she was trying not to let something show.

“Name’s Donna,” she said, pushing her glasses up. “Off the record? A lot of files from those contractor days got messy. Stuff went from Navy to ‘private oversight’ and back again, and when it all blew up in Congress, some people very much wanted it all to go away.”

“Like my father,” I said.

She hesitated, then lowered her voice.

“I can’t open the file,” she said, “but I can tell you who used to sign the investigation reports on cases like his. Retired now. Lives out near the bay. If anyone’s been wondering about Iron Wave all these years, it’s him.”

She wrote a name and an address on a sticky note and slid it across the counter.

COL MICHAEL REEVES – CHESAPEAKE.

“Don’t tell him I sent you,” she said. “He hates being reminded this place still exists.”

The house sat near the marsh, salt grass bending in the wind, an American flag hanging from the porch, faded but still orderly. It didn’t look like the kind of place secrets lived. It looked like the kind of place grandfathers grilled burgers and complained about their cholesterol.

I rang the bell.

The man who opened the door was tall and thin, shoulders still straight despite the years. Gray hair buzzed close. Navy sweatshirt, jeans, bare feet. His eyes flicked to the death certificate, the Jacksonville print-out in my hand, the set of my jaw.

“You must be Clare,” he said.

Not “Can I help you?” Not “Who are you?” Just you must be.

My stomach dropped.

“You knew my father?” I asked.

He stepped back, gesturing me in.

“I knew Robert,” he said. “Come on. You look like you could use coffee.”

The kitchen smelled like old grounds and something fried earlier in the morning. He poured us two cups, black, and sat across from me at a scarred wooden table.

“He was one of the best,” Reeves said. “Not just as an operator. As a human being.”

“Then why did no one tell us there was a chance he survived?” I asked. “Why did I stand in front of a coffin and bury a man who might have been alive?”

He studied me for a long beat.

“You’re sure the voice you heard was his?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And you’re sure about the body? That it was him?”

I saw the casket. The white rose. The officer’s eyes, careful and sad. The sheet over the thing beneath the flag that looked like a body but somehow didn’t feel like one.

“They didn’t let us see his face,” I said. “They said it would be… kinder not to.”

He leaned back with a sigh, rubbing a hand over his mouth.

“You’re not crazy,” he said. “You’re late to a party I’ve been drinking alone at for two decades.”

“Tell me,” I said. “All of it.”

He stared into his mug as he spoke, like the coffee might reveal scripts he’d kept memorized.

“Iron Wave was a mess from the start,” he said. “They sold it as a tech test: underwater communications array, environmental sensors, all that shiny crap. But the real project was buried two layers down under a private defense contract. Your father’s team was attached as the muscle, but there was a second agenda. Human testing. Exposure response. Nobody told the SEALs that part.”

My jaw clenched.

“How do you know?” I asked.

“Because I was the one they called in to clean up,” he said flatly. “The day after the explosion, I flew in from D.C. expecting a salvage op and a standard investigation. What I found was confusion, three separate chains of command, and a contractor company that refused to turn over half its logs.”

“And my father?” I asked. “What did you find of him?”

“Not much,” he said quietly. “Two sets of partial remains pulled from the wreckage. Neither positively identifiable as your father. Two dog tags. One of them his. That was enough for the paper pushers. They wanted closure. They wanted the news cycle to end. They wrote the report, stamped ‘deceased’ on five men, and called it a day.”

My lungs felt too small.

“You let them tell us he was dead,” I said.

“I tried to push back,” he said. “Said we needed more proof. They told me this was above my pay grade. Two years later, a contractor down in Jacksonville called a friend in my old office. Said they’d picked up a man near the shipyard, disoriented, wearing pieces of a SEAL wetsuit with R.H. stitched into the collar. Said the guy insisted he was ‘important,’ that he ‘didn’t belong here.’”

I gripped the edge of the table so hard my fingers hurt.

“What happened?” I asked.

“He was checked into a civilian hospital,” Reeves said. “By the time I tried to get records, he’d been transferred. No forwarding info. No file. It was like he’d evaporated. Whoever had him didn’t want him found.”

“And you didn’t call us,” I said, the anger finally finding its footing.

He met my eyes.

“I retired,” he said. “Partly out of disgust. Mostly because I realized I was either going to die of an aneurysm or of a bullet in the dark if I kept knocking on those doors. But I never stopped checking the obituaries. The veteran registries. The unidentifieds. When your form came across my radar last week…” He nodded at the papers. “I knew it was you.”

I sat back, heart pounding. The kitchen was suddenly too small. The air too full.

“So he’s been out there,” I said, “alive, for who knows how long. And nobody thought to tell his daughter.”

“They never meant for you to know he existed,” Reeves said. “Not this version of him, anyway.”

Rain started to patter against the window. Somewhere in the marsh, a bird cried.

“If he is alive,” I said slowly, “if that call was real… why now? Why after twenty years?”

Reeves shrugged, a tired, helpless motion.

“Memory’s a tricky bastard,” he said. “Sometimes all it takes is a sound, a smell, a word to cut through whatever fog they’ve layered over it. You know what the last thing your father asked me before Iron Wave was?”

I shook my head.

“‘If this goes sideways,’” Reeves said, “’you going to make sure someone keeps asking questions for my girl?’”

My throat closed.

He pushed the Jacksonville article toward me, tapping the print-out of the man on the curb.

“Go,” he said. “See if the sea brought him back. But if you find him, Clare, understand this: whoever sank his name that first time will not be happy he floated to the surface.”

“I’ve already buried him once,” I said, standing. “They can get in line.”

Part 4

Jacksonville smelled like a mix of tar, wet rope, and old stories.

The drive from Norfolk took the better part of a day. I cut through North Carolina with the windows cracked, the humid air moving sluggishly through the car. Somewhere in South Carolina, a thunderstorm rolled in, a sheet of gray that swallowed the road.

I stopped at a roadside diner when the rain got too thick to see through. The neon sign flickered; the coffee tasted like it had been on the warmer since the Clinton administration.

The waitress set a chipped mug in front of me and squinted.

“You look like you ain’t slept in a week, sugar,” she said.

“Something like that,” I said.

She nodded at the compass on the table. “Headed somewhere or running from somewhere?”

“Both,” I admitted before I could stop myself.

She topped off my coffee. “My daddy used to say, if a ghost starts knocking, you either answer the door, or you move. Standing there pretending not to hear just makes ’em mad.”

When I climbed back into the car, I pulled up the voicemail again and listened all the way through.

“Little Star, it’s me. I just figured out who I am.”

I looked at my reflection in the rearview mirror.

“Hold on,” I said to the empty car. “I’m coming.”

Harbor House sat near the shipyards, a two-story brick building with peeling paint and a handmade sign that read: HARBOR HOUSE – FOR THOSE WHO SERVED. A flagpole out front leaned slightly to the left.

Inside, the air was cool and smelled of soup, disinfectant, and too many people trying to get better in too small a space. A bulletin board near the door advertised AA meetings, job fairs, and a flyer for “Vet Art Therapy – Paint Your Story.”

A woman with silver braids and glasses hanging from a chain around her neck looked up from the reception desk.

“Afternoon,” she said. “Can I help you, baby?”

“I hope so,” I said, holding up the printed article. “I’m looking for this man.”

She peered over her glasses, then at me.

“Oh, you’re talking about Mr. Bob,” she said. “Quiet fella. Polite. Helped mop the floors without being asked. We was all kind of fond of him.”

My heart thudded.

“Is he here?” I asked.

Her expression shifted, softened.

“Not right now,” she said. “He left about a week ago. Middle of the night. Got a phone call, came out looking like somebody had just told him he’d won the lottery and lost his ticket all in one breath.”

My fingers tightened on the paper.

“A week ago,” I repeated. “Do you remember what night?”

She considered.

“Tuesday?” she said. “All I know is I was watching that late show with the TV doc who yells a lot, and the phone rang in the office. Man’s voice asked for ‘Robert.’ I told him we had three Roberts on the roster and which one he meant. Long pause. Then he said, ‘The one who used to be somebody.’ Gave me a callback number with a Maine area code, honey, and my eyebrows hit the ceiling.”

My legs felt weak.

“My number starts with Maine,” I whispered.

She nodded slowly.

“Mr. Bob was listening from down the hall,” she said. “After I hung up, he came to the desk shaking, said, ‘It was her. My Little Star.’ Packed his bag in ten minutes. Said he had to go home before he forgot again.”

Something in my chest broke open. A sharp, ragged mess of hope and grief.

“He called me,” I said. “That same night. I missed the first ring.”

“He called you and then he left,” she said. “I haven’t seen him since.”

“Did he say where he was going?” I asked.

She shrugged.

“North,” she said. “Said he needed to find the cold, that the cold helped him think. Mentioned St. Augustine once, said he remembered standing by a fort with a little girl eating shrimp out of a paper basket.”

I stared.

St. Augustine. I was eight the summer we’d gone down to Florida while Dad was between assignments. We’d walked the old fort walls, scooped sand crabs into pails, and he’d bought me a junk-shop compass with a sticky needle and promised it would always point home.

I still had that compass. It sat in my glove compartment, its cheap brass casing worn smooth.

“He remembered that?” I asked.

Miss Lorraine smiled, full of quiet triumph.

“Baby, he remembered something,” she said. “Long as there’s something to follow, a man ain’t all the way lost.”

She rummaged in a drawer and pulled out a file folder.

“We keep notes on everyone comes through,” she said. “Doctor at the VA down on Bay Street said he had amnesia. They tried to get him on a list for long-term care, but you know how that goes. Lots of wait, not a lot of care.”

She slid a photocopy across the desk.

R. HANLEY – M, approx. 55, reported Navy service, claims past as SEAL. Memory gaps, chronic headaches. Responds to name “Robert Henderson.” Hypervigilant near bodies of water. Draws five-point star in margins of paperwork.

In the corner of the page, someone had indeed traced a small, wobbly star.

“For my Little Star,” was scribbled underneath in shaky letters.

My vision blurred.

“Bay Street VA clinic,” Miss Lorraine said gently. “Talk to Nurse Megan. She’ll remember him. And if you see him…” She reached over and squeezed my hand. “Tell him the coffee’s still terrible and his bed’s still open.”

The Bay Street clinic was wedged between a pawn shop and a boarded-up diner, its sign faded but stubborn. Inside, the waiting room buzzed with murmured snippets: “I told them it hurts…” “No, they said I gotta wait three months…” “You heard about…”

A nurse with a ponytail and dark circles under her eyes looked up from the reception desk.

“Hi,” she said. “What can we—?”

“I’m looking for a patient,” I interrupted, then winced. “Sorry. I know you’re slammed. His name is—was—Robert Henderson. Or he might have used Hanley. Navy veteran. Head trauma. Last seen about a week ago at Harbor House.”

She studied my face, then the article in my hand.

“You the daughter he always talked about?” she asked.

I blinked. “He talked about me?”

She smiled faintly.

“Every appointment,” she said. “Didn’t remember a lot of details at first. Just flashes. Called you his Little Star. Said you liked blueberry pancakes and that you hated the dark until he stuck those glow stickers on your ceiling.” She mimed stickers in the air.

My knees wobbled. I gripped the counter.

“That was me,” I said. “I’m Clare.”

Her smile turned sad.

“He’d be real glad to know you came,” she said. “Last time I saw him, his memory was… coming back, I guess. He seemed clearer. Kept asking if we’d heard any calls for ‘Henderson, Robert.’ When the shelter told him they’d talked to you, he just sat there and cried for a bit. Then he said, ‘I gotta go before she gives up.’”

“Do you know where?” I asked, barely able to get the words out.

She shook her head.

“He said he wanted to see a fort he remembered and the ocean with the lights turned off,” she said. “I figured he meant St. Augustine. We got him some bus vouchers and a list of shelters along the way.”

She opened a drawer and pulled out a thin file.

“I’m technically not supposed to show you this,” she said, “but technically, nobody’s supposed to come back from the dead either, so I think we’re past the rulebook stage.”

Inside were notes from years of sporadic visits. Headaches. Disorientation. Sudden anger. Quiet days. On one page, right next to a note that read PATIENT RESPONDS TO THE WORD ‘HENDERSON’ BUT DENIES IT’S HIS NAME, there was a scribbled sentence:

Little Star, if I find you, will you still know me?

I pressed my hand over my mouth.

“Some days he knew he was missing something,” the nurse said softly. “Some days he just looked… hollow. But the last time, when he left? He looked like a man who’d finally found a map.”

I walked back out into the heat, the file pressed to my chest like armor.

St. Augustine was two hours south.

If the road is honest, I thought, it will put him at the end of it.

Part 5

St. Augustine is the kind of town that forgets time is supposed to be linear.

The old Spanish fort crouches by the water, its stone walls softened by centuries of sun and salt. Tourists wander cobblestone streets with ice cream cones and shopping bags. The marina’s masts bob in the distance like a forest of thin, patient trees.

When I was eight, everything about it had felt huge. The cannons, the walls, the sky. My father had pointed out over the bay, pretending to be a tour guide.

“See, Little Star? That’s where the pirates tried to come in,” he’d said. “But the fort stood and the people inside kept fighting. Sometimes staying alive is just about staying put.”

We’d watched the sun slide down behind the bridge and eaten shrimp out of greasy paper baskets, fingers dripping butter and Old Bay. He’d bought me a brass compass from a gift shop, the kind that turns green on your wrist if you wear it too long.

“So you can always find your way back to me,” he’d said.

Now, twenty-something years later, I parked near the marina and sat in the driver’s seat for a full minute, both hands clenched around that same compass.

The needle shuddered. North. North. Always north. Except north didn’t feel like a direction anymore. It felt like a person.

I got out.

The afternoon crowd swelled and ebbed around me, sandals slapping, camera shutters clicking. Somewhere, a street guitarist played a familiar rock song slow and sad.

I walked toward the waterfront, scanning every bench.

Don’t build him in your head before you see him, I told myself. Don’t paste the man from the photograph onto some stranger’s face and decide it’s him just because you need it to be.

When I saw him, I knew anyway.

He sat on a bench looking out over the water, shoulders hunched against a breeze that wasn’t strong enough to justify the curl in his posture. Gray hair poked out from beneath a navy baseball cap, longer than regulation but still neat. His hands were folded around a paper coffee cup, fingers nicked with old scars.

People age. Time has a way of carving itself into a face.

In my mind, my father existed at forty-five, the way he’d been before Iron Wave, lines at the corners of his eyes, strong jaw, steady shoulders. The man on the bench was older. Cheeks hollowed a bit, jaw slack when he wasn’t concentrating, skin weathered by years of hard sun and shifting roofs.

But the profile—that angle of cheekbone, the line of the nose, the way he held his head slightly cocked like he was listening for something only he could hear—that was him.

“Dad?” I said, voice barely more than breath.

He turned.

His eyes were the same.

Gray-blue, shot through with the kind of sadness you only earn by outliving your own story. For a heartbeat, they were blank, scanning a stranger.

Then they widened.

“Little Star,” he whispered.

Every story I’d ever told myself about being strong, rational, prepared disintegrated.

I stumbled forward, one hand pressed against my mouth, the other reaching out and stopping inches from his shoulder.

Up close, there were more scars. A white line along his temple disappearing into his hairline. A knot on his jaw like an old fracture. A thin rope of puckered skin along his forearm—same place he’d sliced it open on our backyard fence when I was ten. I’d helped Mom clean it, pressing cotton balls soaked in hydrogen peroxide, watching the bubbling white foam with morbid fascination.

“You still got the scar from the fence,” I blurted, nonsensical.

He glanced down at his arm, then back at me, a slow, dawning recognition spreading across his face.

“I told you I’d never get rid of it, remember?” he said, voice breaking. “Said it’d be proof I was human.”

I couldn’t hold back anymore.

I launched myself at him, arms wrapping around his shoulders. For a terrifying second, he went rigid, as if no one had touched him in years. Then his arms came up around me. Stronger than I expected. Shakier, too.

He smelled like cheap coffee, sea air, and something that might have been antiseptic. His heart thudded against my cheek.

“I thought you were dead,” I sobbed into his jacket. “I buried you. I folded your flag. I put your things in a box and I tried to live like you were on the other side of something I couldn’t cross.”

His hand slid up to the back of my head, fingers threading through my hair like they had when I was little and feverish.

“I thought I was dead, too,” he said, voice rough. “Some days, I wished I was. I didn’t know… I didn’t remember…”

He pulled back slightly so he could see my face. His own was wet.

“I didn’t mean to leave you,” he said. “I didn’t mean to forget you.”

The words sliced and healed all at once.

“What do you remember?” I asked.

He sank back onto the bench, patting the space beside him. My legs felt like rubber as I sat.

“Not everything,” he said. “Not in order. It’s like someone took my life and shook it up in a jar. Bits and pieces float past, and sometimes I can grab them before they sink.”

He stared ahead at the water as he spoke.

“I remember the boat,” he said. “The op. We were testing that damn comms grid. Reynolds kept pushing to go deeper, kept saying the readings weren’t clean yet. Your old man told him we were already kissing the bottom and that mission safety wasn’t a suggestion. We argued. Then everything shook. I smelled fuel. Fire. Someone yelling ‘abort, abort.’”

He rubbed his temples.

“I remember hitting the water,” he said. “Cold like a slap. Fire above me. I remember thinking, ‘Clare is going to be so mad if I die in some contractor’s science fair gone wrong.’ Then… nothing. Just dark.”

“What next?” I asked.

He shook his head.

“Next thing I knew, I woke up in a room that smelled like diesel and bleach,” he said. “Not a Navy med bay. No flags. No doctors. Just men in plain clothes with regulation haircuts. One of them said, ‘You’re lucky, Reigns. We pulled you out of hell.’”

“Reins?” I repeated.

“That’s what they called me,” he said. “Captain Reigns. Said I’d hit my head, that I was confused. When I told them my name was Henderson, they smiled and nodded and gave me pills.”

He mimed popping one in his mouth.

“Headaches,” he said. “Like someone had wired my skull wrong. Every time I asked questions, the headaches got worse. Every time I pushed, they’d pat my shoulder and tell me I was getting agitated and hand me another pill.”

He stared down at his hands.

“I remember work,” he said. “Lifting. Cleaning. Sometimes in warehouses, sometimes on docks. Always behind fences. They said I was just earning my keep. Said I needed stability before I could ‘go back into society.’ But no one ever told me where society was, or who I’d been in it.”

“How long?” I whispered.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Years. I’d get moved. I’d wake up in a different bunk with a different name on the clipboard by the door. Once it was ‘Bob Hanley.’ I liked that one. Felt almost right. I’d ask about my family sometimes. The men in charge would say I’d had a breakdown, that my mind was inventing people to fill in blank spaces.”

My chest ached.

“I started to believe them,” he admitted. “When you’re dizzy and in pain long enough, you start grabbing any steady story, even if it’s wrong. I knew there was someone, though. A girl. Laughing. Blueberry syrup on her chin. Glow-in-the-dark stars on a ceiling. I just couldn’t pull her name out of the mud.”

He looked at me then, eyes wet.

“Then a few months ago, some doctor at that clinic in Jacksonville smelled like the kitchen from our old house in Maine,” he said, voice low. “I don’t know what it was. Coffee. Cleaner. Something. It flipped a switch. Suddenly I remembered snow. The dock. You in that red coat your mother hated because it clashed with your hair.”

I laughed through tears. “She said it made me look like a stop sign.”

“Exactly,” he said, smiling. “And I remembered saying, ‘Little Star, you’re going to blind the fish.’ It all started… connecting. I went back to the shelter that night and laid down, and all I could hear in my head was you asking me not to go back out on the boat. ‘Promise you’ll come back, Daddy,’ you said.” He cleared his throat. “I hadn’t let myself hear that in years.”

He glanced at me.

“So I found a phone,” he said. “Dialed the old house number. I didn’t even know if it still worked. It rang, and when you answered…” He shook his head. “For a second, I thought maybe I was dead after all, because that was the only kind of miracle I could picture myself getting.”

“You hung up,” I said.

“I panicked,” he admitted. “My voice sounded wrong in my own head. I thought if I stayed on, I’d mess it up. So I left the message instead. And then I got on the first bus going north.”

I let the information settle, the edges still sharp.

“You remembered me,” I said quietly.

“Not all at once,” he said. “But enough to know I had to find you before whatever they did to me erased it again.”

I reached into my pocket and pulled out the old compass, the brass dull and scratched.

“You told me this would help me find my way home,” I said. “Turns out, it found you.”

He took it, turning it over in his hands, thumb tracing the groove where the lid met the case.

“You kept it,” he murmured.

“I kept all of you,” I said. “I just didn’t know which pieces were real anymore.”

He closed his fingers around the compass, then reached for my hand.

“Help me remember the rest?” he asked.

I squeezed back.

“Yeah,” I said. “We do this together now.”

Part 6

Finding him was only the first miracle.

Proving he was who he said he was—that was the second.

We stayed in a small bed and breakfast a block off the water, the kind with mismatched quilts and a bowl of peppermints by the front door. The owner, a widow with soft eyes and a sharp sense of when to mind her own business, handed us a single key and said, “You two look like you got a lot to talk about. Breakfast’s at eight. Coffee’s on early.”

Dad slept twelve hours straight that first night. I didn’t sleep at all. I sat in the armchair by the window, watching him breathe. Every time his chest rose, the twenty-year knot in my stomach loosened a fraction.

In the morning, he shuffled into the kitchen in one of the inn’s loaner robes, hair sticking up, blinking against the light.

“Please tell me you still know how to make blueberry pancakes,” he said.

I laughed, first genuinely in what felt like years.

“I’ve had twenty years to practice,” I said.

Over breakfast, I called Reeves.

“Colonel,” I said without preamble. “He’s alive. I’m looking at him right now.”

There was a long pause.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said quietly. “Robert Henderson really is too stubborn to die.”

I glanced at Dad, who was poking his pancakes like they might vanish if he looked away.

“He remembers pieces,” I said. “Enough to know he was held somewhere off-book. I have his VA records from Jacksonville. They list him as ‘R. Hanley’ with amnesia and reference Iron Wave in the margins.”

“You need DNA confirmation,” Reeves said. “And a doctor who isn’t on some contractor’s payroll to sign off that he’s the man whose file they stamped as dead. Otherwise the Navy will bury this in paperwork until you both forget why you came.”

“I don’t care what the Navy thinks,” I said reflexively. “I care that he’s here.”

“You should care,” Reeves replied. “The only way to keep him safe now is to drag this thing into a light so bright nobody can pretend they don’t see it. I know a medical examiner. Retired. Names Dr. Eleanor Price. She’s got more integrity than most of the Pentagon. I’ll text you her info.”

Dr. Price’s clinic sat on the edge of town facing the marsh, a clean white building with wide windows and a parking lot half full of pickup trucks. Inside, the waiting room smelled faintly of lemon and rubbing alcohol.

She met us herself—a woman in her sixties with silver hair twisted into a loose bun, sleeves rolled up, a stethoscope draped around her neck like she’d forgotten it was there.

“So this is the man who refuses to stay buried,” she said, studying Dad with a frankly clinical eye and something warmer underneath. “You look pretty good for a corpse, Commander.”

“Been called worse,” Dad said.

She laughed and shook his hand.

“Let’s get some samples,” she said. “And then let’s make a few phones ring.”

DNA swabs took minutes. She took my sample too, labeling each tube with precise handwriting. Then she ushered us into her office and shut the door.

“I had a feeling something like this would happen,” she said, flipping open a folder. “You don’t see as many closed casket identifications as I did and not suspect some of them aren’t what they seem.”

She pulled a copy of my father’s 2005 medical report from the file.

“Look here,” she said, tapping a line near the bottom. “Cause of death listed as ‘trauma consistent with explosion.’ Identification: ‘visual confirmation by next of kin.’ No autopsy. No dental match. They had a body, they had your signature, and they had a paperwork deadline. That’s not proof. That’s convenience.”

“I saw someone,” I said, the memory rising like a tide I’d tried to hold back. “They let me see…the shape. They said it was him. I believed them because the alternative was impossible.”

She softened.

“You did what any person in your position would do,” she said. “You trusted the people in uniforms.”

She shot me a dry look.

“Between you and me, that trust has been abused more times than I care to count.”

Dad stared at the report, his jaw working.

“How many other families,” he asked quietly, “are grieving the wrong man?”

“Too many,” Dr. Price said. “But right now we work on this one.”

When the results came in forty-eight hours later, she called us back to the office.

I knew the answer before she handed me the folder. Some things you feel in your bones.

“Immediate family match,” she said. “Statistically conclusive. This man is your father. This man is very much not dead.”

Dad exhaled like someone had cut a rope around his chest.

“So I’m not crazy,” he said.

“Well,” she said, “I didn’t say that. But you’re definitely not imaginary.”

We all laughed, and the sound had a wild, giddy edge.

That night at the inn, I found Dad sitting on the porch steps, staring out toward the water.

“What happens now?” I asked, sitting beside him.

He shrugged.

“Not sure,” he said. “Part of me wants to disappear somewhere with a fishing rod and pretend the world ended in 2005 the way it was supposed to. Another part of me wants to walk into the Pentagon and flip over every table until someone looks me in the eye and says they’re sorry.”

“Do you think they will?” I asked.

He snorted.

“No,” he said. “But they might say ‘regrettable oversight’ in a memo, and that’s as close as that place gets.”

“Reeves wants you to testify,” I said. “He’s talking about hearings. Investigations. Contractors under oath.”

He rubbed his face.

“I’m tired, Clare,” he said. “I thought dying would be the hard part. Turns out coming back comes with homework.”

“Then don’t do it for them,” I said. “Do it for the guys who didn’t make it. For their families. For the next person some private company decides to disappear.”

He looked at me for a long time.

“You sound like your mother,” he said.

“Considering she was the one who told me to never let a man in a suit tell me what reality is, I’ll take that as a compliment,” I replied.

He smiled, then sobered.

“She’d be mad I let my hair go,” he said, tugging at the gray curls near his ear.

“She’d be mad you stayed away so long,” I said. “But she’d forgive you.”

“Would you?” he asked, too softly.

I thought about all the birthdays, the graduations, the empty chairs at the table. About nights at fourteen when I’d stand on the dock, looking out at the black water, listening for engines that never came. About the call in the middle of the night that ripped open twenty years of scar tissue.

“I thought you were dead,” I said. “I grieved you. I built a version of my life around that fact. Knowing you were alive that whole time and I didn’t know…” I swallowed. “It hurts in a way I don’t have words for.”

His shoulders sagged.

“But,” I continued, “I also know now that you weren’t sitting on a beach somewhere choosing not to call. You were trapped. Drugged. Lied to. Used. The people who did that to you are the ones I’m angry with. You… you came back as soon as you could find your way.”

He blinked hard.

“I followed your voice,” he said.

I took his hand.

“Then yeah,” I said. “I forgive you. For being lost.”

He held onto my hand like it was the only solid thing in the world.

The next morning, Reeves called.

“Price sent me the report,” he said. “I forwarded it to some people who still owe me favors. The Oversight Committee wants to hear your father’s story. Closed session. No cameras. For now.”

“Is that safe?” I asked.

“No,” he said honestly. “But keeping this under wraps clearly hasn’t been either. The contractors who ran Iron Wave’s real agenda—they’ve changed names, but they haven’t changed games. They’ve made a lot of money on the back of men like your father. They’re not going to be thrilled he’s walking around with his memory coming back.”

“We’ll come,” I said. “We’ll tell what we know.”

“You’re your father’s kid,” he said. “I’ll send the details.”

When I told Dad, he sighed.

“Guess I better find a blazer that doesn’t smell like salt and mold,” he said.

“If not, you can wear that old SEAL hoodie from the photos,” I said. “Intimidate them into honesty.”

He chuckled.

“Honesty and Congress,” he said. “Now there’s a pairing I never thought I’d see.”

Part 7

Washington, D.C., is impressive in the way of marble tombs.

Every surface in the federal building gleamed. Guards stood like punctuation marks at the doors. Our footsteps echoed down corridors lined with portraits of men who’d made decisions about lives like my father’s without ever getting salt water in their boots.

Reeves met us at the security checkpoint, hair more silver than gray now, cane tapping against the floor.

“You clean up better than I do,” Dad said, eyeing his blazer.

“Retirement’s just an excuse to let the starch out,” Reeves replied, clapping him on the shoulder. “You ready?”

“No,” Dad said. “But let’s do it anyway.”

The hearing room was smaller than I’d imagined. No rows of cameras, no screaming reporters. Just a semicircle of senators in suits, a couple of committee lawyers at a side table, and a row of chairs for witnesses.

Dad sat at the microphone, hands folded, posture straight. I sat behind him, close enough that I could reach forward and touch his shoulder if he needed grounding.

“Commander Henderson,” the chairwoman said, “you were declared deceased in 2005 in connection with Operation Iron Wave. Do you contest that report?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “On account of the fact that I’m sitting here.”

A ripple of uneasy chuckles.

She nodded.

“Walk us through what happened,” she said.

He took a breath and began.

He talked about the mission briefing. About being told they were testing “environmental resilience for comms equipment,” about the civilian techs who talked a lot and listened very little, about the contractor in charge, Captain—no, Mister—Reynolds, who seemed more concerned with pleasing someone on a phone line than keeping the boat afloat.

He described the explosion in clipped terms, but I could hear the images underneath.

“The deck bucked,” he said. “Fire broke out near the stern. We lost steering. Someone yelled that the array had overloaded. I gave the order to abandon ship. After that, it was noise and heat and the ocean hitting me so hard it felt personal.”

One of the senators asked, “You’re certain the explosion was accidental?”

Dad’s jaw tightened.

“I’m certain it wasn’t an act of God,” he said. “Equipment like that doesn’t just spontaneously combust. Not when half the readings had been red for thirty minutes and the contractor in charge said we’d address it ‘after the test window.’”

He told them about waking up in that metal room. About the man who called him “Reigns.” About the pills, the rotating names, the way any mention of “Henderson” got smoothed over with words like ‘confused’ and ‘agitated.’

“Their goal was to make me forget who I was,” he said. “Because a man who doesn’t know his own name doesn’t ask why nobody called his family.”

The lawyer from Defense Oversight leaned forward.

“Do you have any evidence,” he asked, “that this operation was sanctioned at any level above the contractors?”

Reeves cleared his throat.

“I do,” he said, sliding a folder across the table. “Bank transfers, memos, subcontractor agreements. New Horizon Systems—” He tapped the name. “Rebranded now as Horizon Global—billed the Department of Defense for ‘recovery and rehabilitation of test subjects’ after Iron Wave. That’s the language they used. ‘Test subjects.’”

Dad closed his eyes briefly.

“Those ‘subjects,’” he said quietly, “were my men.”

The room went still.

In the days that followed, more documents surfaced. Whistleblowers dug up old emails. Former employees of New Horizon, hiding in comfortable mid-level positions at other firms, found religion or guilt and added their voices.

A picture emerged of a company that had treated soldiers as assets to be repurposed. Men injured in “non-attributable incidents” were quietly “transferred” to private facilities, their identities blurred under the guise of psychological care. Some went home eventually, records scrubbed. Some didn’t.

“Why didn’t you come forward earlier?” one senator asked Reeves.

“I tried,” he said. “My reports were ignored. My access was revoked. My pension was used to remind me that loyalty is rewarded and troublemakers are not.”

“And you, Commander?” the chairwoman asked. “What do you want from this committee?”

He looked at me briefly before answering.

“I don’t want a parade,” he said. “I don’t want my face on a poster. I want an official acknowledgement that what happened to me and my team was wrong. That the families who were told their sons died honorable, clean deaths were lied to. I want policies that keep contractors from operating shadow wars with our people as lab rats. And I want my daughter to be able to tell this story without people patting her hand and asking if she’s sure.”

I felt something in my chest unknot.

On the train back to the hotel, Dad leaned his head against the window and watched the city slide by.

“Do you think they listened?” I asked.

“I think some of them heard,” he said. “That’s a start.”

The story broke big anyway.

Someone leaked enough of the hearing to the press that the morning headlines flashed with variations of: NAVY SEAL DECLARED DEAD FOUND ALIVE, CLAIMS CONTRACTOR COVER-UP. Photos of Dad in his uniform from before, photos of him now in his blazer, hair gray, face lined, eyes still fierce.

Reporters called. Producers emailed. A publisher reached out to me about “a book opportunity.”

Dad ignored most of them.

“I didn’t survive twenty years of being a ghost just to become a soundbite,” he said.

The contractors did not, as predicted, send us fruit baskets.

Men in unmarked suits tried soft intimidation first. A knock on the door of the cottage in Florida we were still using. Two smiles that didn’t reach their eyes, badges flashed too fast to verify.

“We’re concerned about national security implications,” one said. “Loose talk can harm ongoing operations.”

“You mean loose talk about the way you misused your last ‘operation’ is bad for stock prices,” I said pleasantly, standing squarely in the doorway.

Dad stepped up beside me, taller despite the stoop he’d gained.

“If you have questions,” he said, “you can contact my lawyer or the Senate. I’m done talking to people who don’t sign their real names on forms.”

They exchanged a look and left.

“You sure you want to poke that bear?” I asked after the door shut.

“I’ve been poked harder by better men,” he said. “Besides, they’re not as scary now that I know they bleed like everyone else.”

We decided to leave Florida anyway.

“Too flat,” Dad said. “Too many memories of cages and clinics.”

We went back to Maine.

The Henderson house had sat half-empty since Mom died three years before—a place I visited on holidays and kept clean out of obligation and something like faith. Dust sheets off the furniture, windows washed, her handwriting still on sticky notes in the pantry.

Dad stood in the doorway for a long time before stepping inside.

“She’d kill me for tracking mud in,” he said softly.

“She’d kill you for letting your hair go that color,” I said.

He chuckled, then caught sight of the old family photo on the mantel: all three of us at the harbor, my hair tangled, his arm around Mom’s shoulders.

“She’d forgive me for the hair,” he said. “Not for making you stand alone next to a box that wasn’t mine.”

We held a memorial that summer—not for him, but for the four men whose names had been listed next to his on the Iron Wave casualty list.

Reeves flew up, leaning on his cane, grumbling about airports. Cole came too, limping, older, still somehow exactly the same. They stood with Dad on the dock, three men who’d seen too much and lived anyway.

“Here’s to the ones who didn’t get a second shot,” Cole said, tossing a rose into the water.

“And the ones who waited for us to come home,” Dad added, turning to me.

We watched the flowers float out, bobbing on the swell.

“That guilt is going to try and eat you,” I told him later, when he sat on the back steps staring at the tide.

“I know,” he said. “It already has. For years, I thought I must have done something to deserve what happened. That some choice, some mission… this was the bill coming due.”

“That’s not how it works,” I said.

“You sure?” he asked.

I thought about it.

“No,” I admitted. “But I am sure that what they did was wrong. That you being here doesn’t mean they deserved to die any more than you did. That’s not a math problem you can solve.”

He sighed.

“Survivors always think they’re supposed to justify their survival,” he said. “Maybe the bravest thing is admitting there’s no justification. Just the fact that we’re still breathing, and we owe it to them not to waste that breath.”

“Then let’s not,” I said.

We fell into a new rhythm.

He bought a small boat with some of the settlement money the contractors grudgingly released once the investigation started bearing teeth. Just a modest little thing, nothing like the vessels he’d commanded. He took it out every morning he could, weather permitting, sometimes alone, sometimes with a couple of vets from the local support group.

“It’s cheaper than therapy,” one guy joked, clambering aboard.

“It is therapy,” Dad replied.

I went back to teaching part-time and writing the rest of the time. Not a tell-all. Not a revenge screed. Just our story, piece by complicated piece. The call. The drive. The ghosts that turned out not to be.

People reached out. A woman in Ohio whose brother had died on a contractor-heavy op in Afghanistan. A man in Texas who swore he saw his “dead” CO in a shelter five states away. Some were probably grasping. Some might have been onto something.

I couldn’t fix them all. But I answered every email.

“Don’t stop asking questions,” I wrote, over and over. “Even when it hurts.”

The nightmares didn’t vanish when the truth came out. If anything, they sharpened.

Some nights I’d wake to hear the shower running. I’d find Dad sitting on the floor under the spray, fully clothed, eyes far away, water pounding around him.

“Too much fire,” he’d say. “Water helps.”

I’d sit just outside the tub on the bathmat, handing him a towel when he was ready, waiting until the faraway look faded.

Other nights, I was the one who woke up gasping—phone ringing in my dreams, static, his voice saying “Little Star” followed by silence. I’d pad down to the kitchen and stand in front of the landline, half expecting it to ring again.

Sometimes it did. Telemarketers. Wrong numbers. Once, a survey from a political campaign.

“Are you satisfied with the current administration’s handling of national security?” the cheerful voice asked.

I laughed so hard I startled the dog.

“Not even a little,” I said, and hung up.

Healing, I learned, isn’t a straight line. It’s a tide. Some days the shore looks clear and solid. Some days the water climbs back up and sweeps you off your feet.

On the good days, Dad and I sat on the dock at night, mugs of tea in hand, his old constellation stickers now mirrored by real stars overhead.

“See that one?” he’d say, pointing. “Cassiopeia. Looks like a crooked W. Always liked that one.”

“Because it’s the Little Star?” I teased.

“Because it’s stubborn,” he said. “Refuses to line up the way people expect.”

I’d lean my head on his shoulder, the wood warm under us, the sea breathing in and out.

“You know,” he said once, “if you’d given up—if you’d heard that call and decided it was just your brain playing tricks—I’d still be sitting on some bench in Florida, thinking my life ended in ’05.”

“I couldn’t let it go,” I said. “I tried. For years. But every time the Navy’s version of the story started to feel settled, some part of me itched.”

“That itch saved my life,” he said.

“No,” I replied. “Your refusal to disappear saved your life. I just picked up the phone.”

Part 8

It’s been three years since the night my dead father called me.

Some days, that sentence still feels like it belongs to someone else’s life. Usually the part where we tell it at conferences, or when a reporter tacks our story onto a larger piece about military reform and contractor oversight.

Mostly, though, our life now is boring in the best ways.

Dad’s hair has grown out into a respectable silver mop. He wears it with a kind of stubborn pride, like the wrinkles around his eyes—a map of where he’s been, not something to be smoothed over.

He volunteers twice a week at the VA clinic in town, not as a counselor—he’d laugh at that—but as something better. A man who sits in the waiting room with a pot of coffee and a deck of cards, willing to listen.

“I’m living proof you can come back from some pretty wild stuff,” he tells the younger vets. “If I can find my way, so can you.”

The investigation into Horizon Global moved slowly, like all big bureaucratic wheels, but it moved. Executive types in suits had to answer questions they’d dodged for two decades. Families were notified that some of what they’d been told wasn’t accurate. There were apologies, some formal, some whispered.

It didn’t bring anyone back. But some wounds finally started to scab instead of fester.

The Department of Defense held a ceremony last year.

They wanted to present Dad with a medal, a plaque, a new folded flag.

He put on his dress blues—dug out from the back of the closet, pressed and altered to sit over a slightly softer middle. The ceremony was small. The Secretary shook his hand. Cameras flashed.

“For remarkable resilience and continued service beyond the line of duty,” the citation read.

He smiled for the photos, eyes kind, jaw set.

When we got home, he put the medal in the cedar box with the others and slid it back onto the shelf.

“You’re not going to hang it up?” I asked.

He shook his head.

“I know who I am now,” he said. “Don’t need another piece of ribbon to remind me. Besides…” He nodded toward where I was standing. “I already got my proof of life.”

I rolled my eyes to keep from crying.

“Cheap move, Dad,” I said.

“Accurate move,” he countered.

The landline still hangs in the kitchen.

Sometimes I think about taking it down. It’s not like we need it anymore; I pay for the service mostly out of habit and superstition.

But then there are nights when the house is quiet and the sea outside is loud, when the dog snores and the old heater knocks in the basement, and I’ll look at that plastic phone and feel a kind of gratitude that’s hard to explain.

One ring in the middle of the night changed everything.

A friend asked me recently if I believe in miracles now.

I shrugged.

“I think I believe in people refusing to disappear,” I said. “And in the stubbornness of love.”

If you’d asked me in 2008 if I’d ever get to tell my father I was angry with him, that I loved him, that I forgave him, I would have said no. That those words had to be written on paper and burned on the dock, tossed into the water for whoever handles that kind of mail.

Now, every time he forgets where he put his glasses and mutters, “Getting old is a full-time job,” I get to roll my eyes in person.

Every time he yells at the game on TV or insists on burning half the pancakes or calls me “Little Star” when I’m trying to be stern about him overextending himself, a tiny part of me whispers: You’re here.

You’re here.

The landline rang last week at 3 p.m.—a perfectly reasonable hour. I answered on the second ring, heart thumping reflexively.

“Ms. Henderson?” a polite voice said. “We’re calling about your car’s extended warranty.”

I laughed.

“Wrong ghost,” I said, and hung up.

Sometimes I’ll catch Dad standing by the water in the early morning, coffee in hand, lips moving. I don’t eavesdrop. Whatever he’s saying to the swell and the sky is between him and the element that tried to keep him.

My father used to think dying on a mission was the ultimate test of a man. The neat ending. The honorable exit.

Now, he knows better.

“Coming back, that’s the real test,” he told me once, sitting on the dock at sunset. “Learning to live in a world that went on without you. Letting people love you when you’re not sure you deserve it. That takes more guts than any op I ever ran.”

I rested my head on his shoulder.

“Then maybe the bravest thing you ever did,” I said, “was pick up a phone and say, ‘Little Star, it’s me.’”

He smiled at the horizon.

“Maybe the bravest thing you ever did,” he said, “was believe me.”

If you’ve lost someone and there are words sitting heavy in your chest—anger, love, apology, gratitude—say them.

Write the letter. Leave the voicemail. Speak into the wind.

Sometimes they won’t come back. Most of the time, in fact, they won’t. But you’ll know you didn’t let the truth rot inside you.

And sometimes, very rarely, the dead don’t stay all the way gone.

Sometimes they find a way to call you in the middle of a quiet night and say, “It’s me. I just remembered who I am.”

And if that ever happens, I hope you pick up.

I hope you listen.

And I hope, with everything I have, that you don’t stop asking questions until the story you’re living in feels like the truth.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

I Saw an Admiral Wearing My Dead Father’s Ring — What He Told Me Changed Everything

I Saw an Admiral Wearing My Dead Father’s Ring — What He Told Me Changed Everything I spent years serving…

“This Is the Fat Pig We Live With,” Dad Joked — Then His Navy SEAL Friend Said: “Admiral Hayes…?”

“This Is the Fat Pig We Live With,” Dad Joked — Then His Navy SEAL Friend Said: “Admiral Hayes…?” My…

I Sat Behind a Pillar at My Brother’s Wedding — Then a General Said, “Come With Me.”

I Sat Behind a Pillar at My Brother’s Wedding — Then a General Said, “Come With Me.” I never expected…

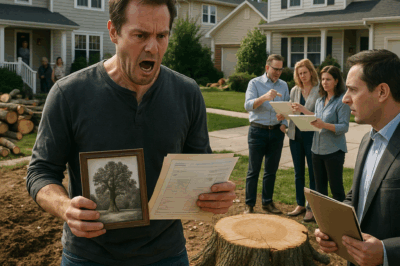

HOA Cut Down My 200-Year-Old Tree… They Didn’t Know It Cost $1 Million!

HOA Cut Down My 200-Year-Old Tree… They Didn’t Know It Cost $1 Million! Part 1 If you’ve never watched…

I Warned the HOA to Stay Off My Land — Now They’re Blaming Me for a $15 Million Landslide !

I Warned the HOA to Stay Off My Land — Now They’re Blaming Me for a $15 Million Landslide !…

My Family Helped Hide His Affair And Called Me Crazy—Until I Exposed Them All

My Family Helped Hide His Affair And Called Me Crazy—Until I Exposed Them All Part 1 The worst part…

End of content

No more pages to load