I gifted my parents a $425,000 seaside mansion for their 50th anniversary. When I arrived, my mother was crying and my father trembling—my sister’s family had taken over. Her husband stepped toward my Dad, pointed to the door, and yelled, “This is my house, get out!”…until I walked in, the room went dead silent.

Part I: Salt Air, Sour Voices

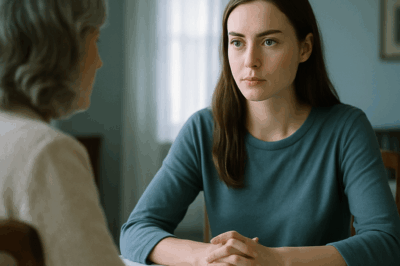

By the time I pushed through the glass door, the Atlantic had blown the curtains into a slow-breathing animal and the whole room smelled like citrus polish and arrogance. My mother was crying—quiet, practiced, like she didn’t want to offend the house I’d bought. My father stood beside her with his hand curled around the back of a dining chair, knuckles pale as bone, his jaw set as if it could carry him through yet another indignity. In the center of the living room, under the vaulted ceiling we’d joked felt a little too cathedral for a beach place, my brother-in-law jabbed a finger toward my father.

“This is my house,” he barked, voice shaking, “get out.”

My father didn’t flinch. That’s the thing about men who came up hard and honest—they know how to hold still while a wave slaps and recedes. But it struck me how small he looked in that moment, and I hated it, because my father is not small. He was the first person to show up at my little league games and the last to leave a busted engine in the garage. He taught me how to read an oil gauge before I could read a chapter book, and he never once asked me to be less around people who were more.

My sister saw me first. Hannah’s eyes went wide, darting to Mark, back to me, doing the math. She hadn’t expected me this weekend. That was the point. In their heads, I wasn’t going to be here to ruin the story they were trying to tell about themselves.

The house itself seemed to recoil at Mark’s voice. It’s a place that took me months to find: cedar shingles scumbled gray by salt, a deep porch, a ribbon of beach that feels private even if the law says it isn’t. I’d chosen everything with my parents’ hands in mind—banister smooth enough for my mother’s palm, stairs my father could take slow if time ever decided to be cruel. It was the kind of house that forgives a life. I bought it for their fiftieth anniversary because I wanted to hold their love up to a horizon and say, “Look. This is what you built.”

I set a black folder on the marble island the way some men put down a holstered weapon. Mark half-turned toward me, the room’s charge shifting the way it does when a thunderstorm decides whose backyard to punish.

“You weren’t supposed to be here,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “And yet.”

There’s a face certain men wear in their thirties—men who’ve had just enough luck to believe they’re good at life but not enough history to know the bill always comes due. Mark wore that face. He had the two-handed handshake the first time I met him: as if he could smother your suspicion with his palms. He complimented too easily, and his compliments always had a wobble in the middle, like a person who hadn’t actually tasted the wine he’d just called “exceptional.” Hannah glowed, and I wanted to be wrong, because love, to me, has always been a reason to give a person one more inch of grace than they deserve.

“Mark,” I said evenly, “you’re yelling at my father in a house I bought for my parents. That’s a choice.”

He had the nerve to grin, a flicker of it, before he remembered to set his jaw. “We clarified the title,” he said, aiming the sentence like he’d practiced it in a mirror. “It’s ours now—family consolidation—tax strategy.”

I looked at my mother. She wiped under one eye. My father’s jaw flexed.

“Family consolidation,” I repeated, letting the words taste like tin. “Fascinating.”

I flipped the folder open. Pages whispered. I slid one across the island’s stone. “These are the original trust documents.”

He didn’t immediately pretend to read them. His eyes tracked the seal, the signature, the notary stamp, the clause that said nothing moves without me. He glanced at Hannah. She flinched.

“You forged their signatures, Mark,” I said, not unkindly. “You filed a transfer using the wrong deed number, the one tied to my trust account. You used a notary who’s been dead since 2021. You moved your things into my parents’ anniversary gift and started calling it yours.”

He sputtered the way a lawnmower sputters when a stone jams the blade. “We… I… no one is saying… you’re misunderstanding the—”

Behind me, the ocean hit rock and receded. The room went very still, as if the house wanted to hear the next sentence better.

“Effective today,” I said, sliding the next paper across, “you are trespassing.”

Hannah’s breath hitched. Her hand came up to her mouth, and for a flicker of a moment she looked like the kid who used to crawl onto my bed when thunderstorms cracked our roof and tell me if I held her hand, the lightning couldn’t find us.

“Evan,” she whispered. “I didn’t know.”

Maybe she didn’t. But ignorance is a pet that eats more than you expect. It grows until you’re feeding it every room in the house.

Part II: Before the Thunder

Two months earlier, when the realtor called to say she’d found “the one,” I wasn’t thinking about fraud. I was thinking about the way my father looked at the ocean like it was a joke God had told a thousand times and he still wasn’t done laughing. I was thinking about the way my mother folded dishtowels, edges aligned, like order was an act of love. I was thinking about a porch swing and the way fifty years sits more comfortably in a chair by a window than in a condo that looks at a billboard.

We’d walked through five houses that weekend. Each had a flaw. One had a view that made you stupid and a foundation that made you prayerful. One had neighbors who believed leaf blowers were a personality trait. One felt like it had been built by a man who hated corners. Then we turned into a gravel drive and the Atlantic shrugged itself into view. My mother’s mouth made a small O. My father whistled, low and soft, the way men of his generation whistle when something makes them sentimental in public.

“This one forgives,” my mother said, running a hand along the banister. She’s always said that about people and places she believes deserve their second chances. “It forgives and it keeps a secret.”

I set up a living trust for the house because my job has taught me that love is not the opposite of paperwork. My attorney, Mina, drafted the documents with the kind of legal music that makes courts stand up straighter. I signed; the bank stamped; the county recorded. Then I wrapped a key in tissue, slid it into a small blue box, tied a white ribbon, and placed the box in my mother’s palm. My father looked like a man trying not to run in church.

We had six good weekends. Then I got a call from the bank manager. She used my first name in a voice she reserves for letting people down easy.

“Evan, we received a request to transfer title on the ocean property. The instruction references your trust. Can you confirm authorization?”

I took a breath that didn’t go anywhere. “Who’s the transferee?” I asked, but I already knew.

“Hannah Carter-Bailey,” she said. “It says family consolidation. The documents include a notary attestation. The signature appears—well—”

“Smudged?” I said. “Darker than it should be?”

“Yes,” she said softly. “And the deed number they used is not the parcel’s. It’s the account number for the trust itself.”

I thanked her. I hung up. I pressed my thumb and forefinger to the ridge of my nose and waited for the anger to arrive. It didn’t. I felt something better: clarity. Timing, I reminded myself, is the sharpest blade you own.

I called Mina. “How criminal do you want to be?” she asked, which is her dark way of asking if we’re going to need a judge or a friend at the bank.

“Not very,” I said. “Not yet. I want him to learn.”

We compiled. The notary stamp? Belonged to a woman named Alma who had been buried three years earlier under a headstone that said “Beloved mother” and “Always on time.” The digital signature? Came from an IP address in the co-working space Mark liked to post about. The signatures that were supposed to be my parents’? One loop too neat on my father’s name. A lowercase i where my mother always dots with a tiny heart if she’s distracted or happy.

I called Hannah. She picked up on the fourth ring, voice buoyant with a kind of joy I recognized—I had felt it myself when a thing I wanted for a long time finally said yes.

“Evan! You’re going to love this. We’re making the house the family hub. Already got a contractor. Mark says if we rip out—”

“Stop,” I said, gently. “Did you sign anything?”

“Just a couple places,” she said. “Mark said it was paperwork. You know. The boring stuff you like.”

“I like paperwork that’s true,” I said.

I didn’t tell her everything. You don’t alert a trespasser you’ve noticed the window open if you want to catch his footprints. Also, she’s my sister. Love makes me gentler than sense sometimes.

I let them move in. I sent flowers. I said nothing when they hosted his investors and called it “our place.” I said nothing when he posed in what he called “my ocean office.” I said nothing when my mother called and said, “We can’t find our binoculars,” and I thought, They’re in a box labeled ATTIC with masking tape written in a hand that is not mine, because I’ve always labeled with a marker and a line under the title. Then the anniversary crept closer, and I said to my parents, “Let him throw the party. Trust me just this once.”

Part III: The Confrontation Everyone Pretended Was a Party

Mark stacked his guest list with the kind of people he thought could prove he’d won. Two investors with shiny watches and sincere shoes. A neighbor who knew the HOA president by first name and liked to tell landscapers where to park. A college friend who’d found success selling something between cryptocurrency and a breath mint.

He didn’t invite my parents’ oldest friends—the ones from the factory floor where my father spent thirty years, or the church ladies who brought casseroles when I broke my arm in third grade. He invited applause. It came in the right moments, and he practiced receiving it in the bathroom mirror, I would wager, because he walked into the living room with a script and a jaw and a tie he thought made him look like a man who owned a thermostat.

I texted the bank manager: “Stand by.” I texted Mina: “Now.”

I walked in. The air changed. My mother said my name like a question answered. My father straightened a millimeter, which in father speaks reads as a mile. Mark said the line about “my house,” with a finger pointing at an old man who could still fix a carburetor barehanded and had never pointed in anger at anything but a map.

I opened the folder. I put papers on marble. I let the house hold silence that smelled like lemon and justice.

Mina is not tall, but she has a presence that makes tall people decide they’ll sit. She stood beside me with her hands folded like patience itself. When Mark blustered about “confusion,” she mentioned the notary’s death certificate and the IP trace and the trust clause that reads like a steel door. You could feel the room process the word felony. It’s dense. It has gravity.

The officers came. They didn’t thunder. They did not pose. They read, nodded, took keys, asked if anyone wanted to claim the monogrammed cutting board with Mark’s last name on it. The investors pretended to receive urgent texts. The HOA-familiar neighbor discovered his shoes needed to be somewhere else. The ocean outside drummed its approval against rock.

“You’ll regret this,” Mark snarled as they guided him down the steps.

“I already did,” I said. “For months.”

Hannah pulled in on herself like a curtain. The line she’d walked—love on one side, convenience on the other—had finally frayed and snapped and she was wearing the half that couldn’t keep her warm. “I didn’t know,” she said. “I swear.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But you didn’t ask. There’s a difference.”

I left her with a symbolic key: the one I’d wrapped for the gift box, the one with a ribbon and a note that had once read, “For the house where you will always be welcome.” I tucked the note underneath the ribbon again, but this time I wrote something else: “Buy your own. Earn it.”

Part IV: The Morning After a Storm Is Too Bright

The locksmith came at eight and left at ten. He was kind enough not to talk about the news, which travels faster than wind when a house glows with scandal. He installed deadbolts and a keypad and taught my father how to reset the code, which my father did twice, because men like him keep practice in their pocket.

We ate leftover cake for breakfast and eggs for lunch and potato salad straight from the bowl at four because my mother has always believed parties are a meal group that begins and ends with mayonnaise. The neighbor came over with crab dip and the kind of apology that doesn’t try to reinvent history. He’d been fooled, too—some men are good at making belief feel like a compliment.

Mina filed what we’d promised we’d file. The DA sent a letter later that week that said words like “deferred” and “compliance.” I had insisted on mercy. Prison ruins people and bends families in the middle. Shame will be punishment enough, I thought, and I still think so. Shame makes mirrors heavier.

Hannah moved into a rectangle of an apartment with a balcony barely big enough for a chair and a plant. She texted me a photo of a basil that looked like it wanted to live. “Look,” she wrote. “Green.” She came over to the house three times in the first month, and each time she stood at the edge of the deck like it might push her back, and each time my mother hugged her like she’d learned anything other than love. My father installed a coat hook at Hannah’s height, and he made sure not to call it permanent.

Mark sent me three emails, eight texts, and two letters. The letters were better. Paper slows a man down. He wrote about confusion and misunderstanding and family and business. He wrote about the ways the world had been unfair to him when he’d been so close, so close, to catching it. He wrote one sentence that I believed: “I thought kindness was a green light.”

I didn’t respond. He wasn’t talking to me, anyway. He was writing to the jury of men he hoped existed who would read his footnotes and clap. Some men never get used to the quiet that follows a no.

I transferred the house from the trust to my parents’ names. Mina approved. The bank manager smiled with teeth that said she was happy for us. At the county clerk’s office, I handed over a form and a donut. The woman behind the glass took both and said, “It’s nice when good things happen to good people.” I didn’t tell her that the world isn’t that neat. I let the neatness live in that sentence for the afternoon.

My parents began the business of soaking in their fifty-first year in a house that wanted none of us to try so hard. My mother watched the water like it was a hymn. My father fixed a hinge that didn’t need fixing. They argued about whether the hydrangeas would mind more sun. He insisted on installing a dimmer switch in the hallway because he doesn’t believe in lights that only know two ways of being.

I slept in the guest room and woke with the unmistakable sense that I’d stopped carrying a door I didn’t even know had a handle. It felt like relief you can’t justify to anyone who hasn’t stood where you stood and thought, I need to be careful if I want to remain kind.

Part V: The Cost of Being Done

I’m not proud of how long it took me to see Mark clearly. He was good at throwing blankets over problems: money, charm, the right wine. He was good at using Hannah as the reason and my love as the excuse. He seemed like the kind of man who could be kept in check by a mortgage and a couple kids. Men like that never plan to steal until they realize they can.

My mistake wasn’t the trust or the paperwork—my mistake was assuming paper would keep him away from people. He got in through the soft door: my parents’ belief that anyone around their daughter’s laughter must be a guest. They signed where they were told because Hannah said, “It helps,” and they’d watched me help from the time I had hands. He used the trust because he thought a trust was like a person—swayable, if you knew what to say. He used the dead notary because he thought the dead are done speaking. He used the bank because he thought institutions ultimately bow to persistence.

He didn’t plan on the part where someone who loves quietly is also a person who pays attention.

When I walked into the house that night and saw my father’s hands—those hands that built me a treehouse and a resume and a way to say sorry without sounding like a child—I felt something settle. Not anger. Not even hurt. A kind of finality.

“Are you okay?” my father asked me on the porch later, as if it mattered more to him than whether he’d be allowed to stay.

“I am,” I said. “Are you?”

He nodded. “I’m not embarrassed,” he said. “Not anymore.”

“Me neither.”

He put his elbow on the railing and looked out at the endless thing men look at when they need to put themselves into a sentence that includes the word small and the word okay. “I never liked that boy,” he said, which made me laugh, which made my mother say from the kitchen, “Don’t wake the neighbors with all your cackling,” which made us laugh harder, which is how families save each other.

Hannah walked out with three mugs of coffee and sat on the steps, and for a minute we were the kids we used to be, the ones who ate cereal at midnight and watched storms. “I signed something I didn’t read,” she said, not looking at either of us. “I thought if I trusted him, he’d keep trusting me.”

“Trust isn’t a favor,” I said. “It’s a contract. You can’t keep signing if he keeps breaking it.”

She nodded. “I know.”

I did something then I don’t do often. I reached out and took her hand. She didn’t pull away. The ocean threw a couple waves casually against the rock, like it wanted to end the scene with applause and didn’t care that we were being sentimental. When we went back inside, the house kept our secrets and the hydrangeas leaned a little toward the window.

Part VI: The Long Ending

Six months later, a man at a grocery store I don’t know called me a hero because he’d heard the story on the kind of breeze that blows status updates through neighborhoods. I said I wasn’t. I said I was a son. Which is to say: someone who does the work in front of him and tries not to make it performative.

Mark’s startup limped along long enough for one investor to say, “We’ll circle back,” which is venture-speak for “We’ve circled and there’s no back.” He moved into a rental that had a view of other rentals. I hope he learns. I don’t need him to. Life eventually gives quizzes on chapters you skipped.

Hannah got a job at a dental office doing billing and learned the way money moves when it’s earned. She calls me when she does something boring but grown: “I balanced a budget,” “I said no to a dress,” “I called Mom before she called me.” The first time she made a car payment on time, she texted me, “It felt like choosing myself.” I wrote back, “That’s what it is.”

My parents’ house smells like coffee in the morning and garlic at night. There’s a calendar on the fridge with my father’s block letters and my mother’s circles around the days I’m supposed to be there. I don’t always make it, but the circles make me try. In the backyard, my father has built a ridiculous bench that faces the sunrise and says, in a wood-burned script that is absolutely my mother’s doing, “Sit. Breathe. Be married.” They let other people sit there, which is the whole thing about my parents—everything they build is for everyone else, including, finally, themselves.

I keep the black folder in a drawer, and sometimes I take it out just to remember that paper can be a shield instead of a sword. There’s a copy of the dead notary’s obituary tucked inside because the dead deserve to be more than a stamp. There’s a Post-it in Mina’s writing that says, “Proud of you,” which I keep because lawyers don’t say that kind of thing out loud unless it’s true. There’s a dried piece of ribbon from the symbolic key I gave my sister, and there’s a list in my handwriting of the dates that mattered between the first bank call and the night the officers took Mark to the door. I am sentimental about paperwork. It’s a flaw. It’s also the reason my parents still watch the ocean from the porch that forgives us.

When people ask for an ending, I don’t tell them the one they expect. There was no fistfight. No dramatic revelation scored by a string section. There was a folder, a phone call, a door, and a road. There was a man who thought ownership is something you can talk into being and a family that decided to be quieter and therefore stronger than that. There was my mother’s face the next morning as she watched the water like it was an episode she couldn’t pause. There was my father’s hand on my shoulder and the weight of fifty years in his palm.

There is this: I stand at the edge of the deck sometimes and let the salt wind make a mess of my hair and the gulls critique me. I think of the moment I walked into the room and everything went quiet. I think of the way kindness can be mistaken for weakness. I think of the way anger makes me sloppy and orchestration makes me proud. Then I go inside and cut fruit for breakfast and laugh at whatever joke my father tells and put my mother’s coffee on the little tray with the ridiculous floral design she refuses to throw away.

Some victories don’t need words. Some houses remember good news. Some men learn to stop pointing at things that don’t belong to them. And sometimes, if you do the paperwork and you wait for the right moment, a house by the sea lasts long enough to hear the people inside it say thank you to each other without anyone being asked to leave.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

An Unknown Number Called Me It Was His Ex What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew

An Unknown Number Called Me. It Was His Ex. What She Said Shattered Everything I Thought I Knew Part…

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law

The Bride Slapped a Server at Her Own Wedding, Not Knowing It Was Actually Her Mother-in-Law Part I —…

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am

HOA Karen Called 911 After I Slept at My Cabin—Then Froze When She Learned Who I Am Part I:…

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side?

When is THAT ONE time that you had to turn to the dark side? Part I — The Unicorn…

“We’re Taking Your Lake House For The Summer!” Sister Announced In A Family Group Chat. I Waited…

“My sister said, “We’re taking your lake house for the summer,” and everyone in my family agreed. They drove six…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes…

My Mother Asked Who I Wanted To Marry. This Time, I Didn’t Choose Simon Hughes… Part I: The Answer…

End of content

No more pages to load