I gifted my daughter the family home, trusting she would honor it. But her husband told me the garage was “my place.” He didn’t know I had one call left to make….

Part One

The garage door creaked open, a blast of cold air making me pull my cardigan tighter. This was my reward for giving my daughter everything. Fifty feet away, my warm house glowed, my son-in-law’s laughter drifting through the night.

“You’re welcome to join us,” my daughter, Jessica, had said earlier, not meeting my eyes. “But Andrew thinks it might be awkward.”

What I knew was that Andrew Reynolds thought I wasn’t good enough for his precious image.

Six months ago, I’d signed over the family home to Jessica. Then the “temporary arrangement” began. My things were moved from the guest suite to the unheated garage.

Tonight, I knocked on my own front door. “Mom, we’re in the middle of dinner,” Jessica said, keeping the door half-closed.

“It can’t wait,” I said, my voice carrying to Andrew and his guests. “I’ve been diagnosed with a respiratory infection from living in that garage.”

Andrew appeared, his perfect smile fixed in place. “Eleanor, you’re embarrassing Jessica.”

“Am I embarrassing you, Jessica?” I asked. “Or is it embarrassing that your mother has pneumonia from sleeping in a garage while you host dinner parties?”

Her face crumpled, then hardened. “You’re being dramatic. If you’re unhappy, perhaps you should consider other options.”

My own daughter was suggesting I move out. I walked back to the garage, my heart breaking. That’s when I made the call.

“George,” I said to my late husband’s business partner. “It’s time to execute the contingency plan.”

It was the plan my husband, Daniel, and I had drafted at our kitchen table the spring before he died. He had a legal pad, a pencil worn to a nub, and a stubborn faith in people that life had whittled but never taken.

“Promise me we’ll protect you from… optics,” he’d said, eyes tracking the word he hated. Optics belonged to Andrew. It was the ribbon he tied around anything mean to make it look pretty.

I promised. Then we called George.

George Meyer had been Daniel’s business partner for twenty-nine years—just long enough to know the difference between a handshake and a trap. He sat with us for two afternoons in a row, notepad open, reading glasses midway down his nose.

“People can be complicated when grief and property sit at the table,” he’d said gently. “Let’s build something that works if everyone behaves. And something that works if they don’t.”

We created a trust. Not the kind a realtor waves at a camera—this wasn’t cosmetic. It was old-fashioned muscle in careful legal clothing: the Summers Family Home Trust. Title to the house moved into the trust. Jessica was named the remainder beneficiary. I was granted a lifetime right of occupancy—not the paper-thin sort that can be bullied, but a right with teeth: equivalent accommodations to the primary suite and habitability standards matching the main residence. Any violation allowed the trustee to remove other occupants and suspend the beneficiary’s interest.

We also layered in a springing power of appointment. If the trustee documented elder neglect or abuse, my lifetime right expanded: I could appoint the remainder to another heir or charity. The trust even had a practical, undramatic “Care Covenant”—household expenses were to be paid proportionally by the trust and the beneficiary, with the trustee authorized to hire outside help if “family dynamics impair care.”

Daniel’s crooked grin had brightened at that clause. “Family dynamics,” he’d said. “A kind way to say ‘when people act like fools’.”

We signed in June. Daniel died in August.

I didn’t tell Jessica every detail. We told her the house was “in trust for estate planning,” which was true, just not the whole story. Andrew smiled in a way that said he was already rearranging the furniture in his head. I should have noticed how quickly he started calling the master suite my office on walk-through FaceTimes with his clients.

After the funeral, the casseroles stopped, and the “stay with us for a while, Mom” turned into boxes labeled with masking-tape names. Guest towels. Winter coats. Eleanor’s books.

It wasn’t immediate, the garage. It started sweet. Jessica set up a bed in the guest suite. Andrew set a printer on the dresser “for convenience.” The printer grew into a desk. The desk grew into a ring light and a green-screen panel that chewed up the corner like kudzu. “Two weeks, tops,” he promised.

Two weeks became a month. The night I found my jewelry box in the hallway, a folding table leaning against my closet like a bouncer, I knocked on the master bedroom door to ask if I should move anything.

Andrew didn’t look up from his laptop. “Oh, yeah. Honey?” He called through the bathroom door to Jessica. “We’re thinking the garage for Mom’s things until the reno. My videographer says the guest bath’s tile is a no-go on camera.”

Jessica emerged with mascara wand still in hand. “Just while we paint,” she said, not meeting my eyes. “Temporary.”

Temporary is a liar’s word. It lets you put cruelty in a paper cup and call it lemonade.

By winter, the space heater in the garage was a weak candle against the drafts. On windy nights the aluminum door shivered like a frightened animal. I installed a second lock from the inside. I stopped listening to Andrew tell me I was “choosing this” because I hated heat. I stopped asking Jessica if we could “just talk,” because her face would fold and unfold in the same practiced pattern—worry, then annoyance, then a plea that was mostly an order: “Please don’t make this harder.”

I held out through chest colds and cough drops and hot tea in travel mugs. I held out until my primary care physician pressed her palm to my shoulder and said, “Eleanor, this isn’t safe,” and wrote down atypical pneumonia and “exposure to cold conditions.”

That’s what I told Jessica on the doorstep, in front of the people drinking wine under my pendant lights. That was the moment Andrew said I was embarrassing her. That was the moment Jessica’s mouth hardened around the words other options.

I dialed George from the cold. The call went to voicemail. He was a morning person. I left a message, voice flat with the kind of calm you learn after decades of being a kindergarten teacher—Daniel used to joke the school had turned me into a hostage negotiator.

“Time to execute the contingency plan,” I said. “I’ll bring documentation.”

I hung up and sat on the narrow cot in the garage, the thin mattress pushing the cold back into my bones. The single naked bulb cast shadows on the concrete. On the workbench, the little carved duck Daniel made our first year of marriage still held paper clips in its wooden beak. I picked it up and held it until the shaking stopped.

The night went on without me fifty feet away. I could hear Andrew’s laugh falling over the music. I got up twice to cough and once to add another sweater. On Dan’s old pegboard, the outline of his missing hammer glowed in dust as if he’d just lifted it and would be right back. I cried once, quietly, into my scarf, because there’s a certain kind of crying that belongs to garages, the kind that knows walls hear and do not answer.

By morning, frost feathered the bottom of the garage door. I shuffled across concrete that bit like ice and texted my neighbor, Lydia: Could you drive me to Dr. Hart at 9? Lydia had known me since the year Jessica learned to ride a bike and Andrew learned that my hedges were not to be “trimmed for curb appeal” without asking.

Of course, honey, she wrote back. And I have a thermos of real coffee. The good kind.

I tucked the doctor’s note and my breathing test printout into a manila folder. Then I added: photos of the garage setup; screenshots of texts where temporary grew into maybe spring?; a video from my old phone showing the breath I exhaled turning white in the beam of a flashlight at 3:12 a.m.; receipts for the two space heaters I bought myself; a photo of the outlet they shared that had left a scorch kiss on the drywall.

George texted at 7:06: I heard your message. Come to the office at 10. Bring everything. Then, after a pause: I’m so sorry it came to this.

George’s office smelled like good paper and older leather. He stood when I entered, walked around the desk, and—without the performance some people put on when they think comfort is applause—he hugged me like a friend whose hand you would hold in a dark hallway.

“Let’s get you warm and housed,” he said, as if it were the most natural sentence in the world. He poured coffee, took the folder, and paged through without hurry, reading everything: the diagnosis, the texts, the video stills. He grunted once at the scorch mark photo.

“It’s enough,” he said, tapping the folder. “More than enough.”

I sat on the visitor chair, hands wrapped around a mug as if it were a small, obedient sun. “We did everything Daniel asked?”

“And then some,” he said. “We weren’t paranoid; we were prudent.” He smiled, and the smile didn’t reach his eyes. “Tell me everything again, slowly, like I’ve never heard it. If we end up in front of a judge, detail wins the day.”

So I told him. All of it. The gradual banishment repackaged as logistics. The party lights visible under the garage door like a lit stage seen from backstage. The way Jessica would text are you okay? and then silence the thread when I answered honestly. How the good blanket from the guest room disappeared one afternoon and reappeared weeks later on a couch back, fluffed for company.

When I finished, George closed the folder. “Okay,” he said. “We proceed in two lanes.”

“Two?”

“One: the house and your rights. Two: Andrew.”

My fingers tightened around the mug. “Andrew?” I tried to make the word sound like a question and not a curse.

George leaned back. “He doesn’t know it, but a lot of what makes Andrew’s world sparkle still threads through Daniel. We didn’t sever every tie when he passed. We tied some threads tighter.”

Daniel had kept his majority in the company private. He trusted George. He didn’t trust shiny—his word for men who wore ambition like cologne. Andrew was shiny.

“What kind of threads?”

“Employment. Contracts. Guarantees.” George slid a single sheet across the desk. The first clause was simple enough that a tired woman could understand it: the company—Daniel’s and George’s—had taken an equity stake in Andrew’s marketing firm two years ago, a bridge investment when Andrew made big promises and short invoices. The guarantee attached to that stake had a behavioral clause. Public conduct causing reputational harm to the company or its principals triggered a right to buy out Andrew’s share at a preset, less-than-flattering valuation.

I looked up. George’s mouth twitched. “Daniel never wanted Andrew broke,” he said. “He wanted him to have incentives to be decent.”

“And the company can… choose when to call that clause?”

“We can, if we have cause. For the house, though, we do not need Andrew. We have the trust.”

He paged to a copy of the trust instrument, my handwriting on little flags marking the clauses that mattered now. Right of occupancy. Equivalent accommodations. Abuse trigger. Trustee powers. I read them again, and they steadied my stomach. It felt like touching a stair rail in the dark and finding it still there.

“My plan is simple,” George said. “We issue a formal notice to Jessica as the remainder beneficiary: the trust’s standards have been breached, your lifetime right has been interfered with, and immediate corrective measures are required. We copy counsel. We include the physician letter. If they comply—heat on, guest suite restored, apologies made—we stop at enforcement. If they do not, we suspend Jessica’s beneficial interest pending review, appoint a property manager for the trust assets, and initiate removal proceedings for any occupant not respecting the covenant.”

“Remove Andrew.”

“Remove anyone the trustee deems an obstacle to your occupancy.” He looked at me over the frames. “I’ll be blunt: if Jessica chooses to align with Andrew against the trust, her interest goes into suspension. Not forever, necessarily. But until there’s compliance.”

If you had offered me heroin or that sentence, I would have chosen that sentence. Not because I wanted Jessica punished. Because I wanted the scales to stop pretending they were balanced.

“And Andrew?” I asked.

“Andrew gets his own separate letter from company counsel,” George said. Another paper slid toward me. Different letterhead. “He’ll receive notice that his conduct appears to constitute reputational harm: elder neglect is not just ugly; it travels. We invite him to meet and, ideally, resign his board advisory position and accept a tidy buyout. If he refuses, we proceed under the clause.”

“You’re not… firing him.”

“I’m giving him a door to walk through like a gentleman,” George said. “If he locks the door, we have a key.”

“How fast?”

“Fast.” He checked his watch. “The trust’s notice will be couriered today to your front door and emailed to Jessica. I’ll also file a memorandum of occupancy rights with the county recorder before close of business. It puts the world on notice that you and the trust are not to be trifled with. Tomorrow morning, I’ll have an HVAC team at the house to inspect and restore heat in the guest suite. The trust pays, because the trust protects you even when your child forgets how to.”

I stared at the papers. It had taken months for the cold to creep up my bones. It took ten minutes for warmth to take root again. “And me?”

“You,” he said, “are coming to my wife’s for dinner tonight. Elaine insists. I won’t have you eating soup out of a thermos in a garage while I send letters.”

I laughed then—too loud for the room, too grateful for the absurdity. “George,” I said, “if I end up crying into your wife’s pot roast, you have to promise not to tell me I’m dramatic.”

“I’ll tell you you’re human,” he said. “And then I’ll pass the potatoes.”

Lydia drove me home. She watched while I walked up to the front door and slipped the thick envelope from the courier’s hand with a nod. He pointed at the signature line on his pad. I signed my name with the extra flourish Daniel used to call my teacher underline.

Jessica opened the door before I could turn the knob. She had her phone in her hand like a small shield. “Mom,” she said too brightly, “we can talk later? Andrew has a client call.”

“A notice was delivered,” I said, holding up the envelope. “From the trust.”

She blinked. “The what?”

“The trust that holds title to this house,” I said. “The one your father and I set up last summer.”

The color drained from her face the way it does when a person realizes the truth was in the room the whole time wearing sensible shoes. “Andrew said we needed the deed in my name. For refinancing.”

“Andrew says a lot of things,” I said. “This one is more complicated.”

Andrew’s voice floated from the kitchen. “Jess?” It was the voice you use with skittish dogs. It was the voice he used on me when he wanted to move furniture I was sitting on.

“George sent a notice,” Jessica said into the house. “About the trust.”

Silence. Then the measured footfalls of a man auditioning for the role of Calm. Andrew appeared, jaw tight, smile polite.

“Eleanor,” he said, the way dental hygienists say, You may feel some pressure. “This is unnecessary.”

“Then it will be easy to comply,” I said, surprised at how quickly the response came. Part of me thought Daniel had said it through me.

“We’re in the middle of a quarter,” he said, as if the calendar could defend him. “It’s not a good time for…” He gestured, an elegant wave meant to convey your feelings and my inconvenience in the same arc.

“For honoring the care covenant?” I said. “It’s exactly the right time.”

He looked past me to the driveway and stilled when he saw Lydia leaning on her sedan, arms crossed, watching. He turned back. The smile curdled. “You’re making this adversarial.”

“I’m making it formal,” I said. “So no one gets to pretend later they didn’t understand.”

He glanced at the envelope again, then at the house. Calculating. “Let’s schedule a discussion with your… trustee.”

“At 3 p.m. tomorrow,” I said. “Here. With the HVAC crew.”

He let out a quick laugh. “You went to a lawyer in the night?”

“A business partner’s office,” I said. “And I didn’t go in the night. I went in the morning. I slept in the garage last night.”

Jessica’s eyes flicked—shame, then fear, then something like anger not at me, but at the part of herself that knew better. “Mom,” she said, lower, “you always make it sound worse.”

“You make it look better,” I said softly. “That’s not the same thing.”

She backed away. “We’ll talk tomorrow.”

“You’ll read the notice today,” I said. “And you’ll turn the heat on in the guest suite now. I’m moving back into my room.”

Andrew’s mouth opened. Closed. “No, you’re not.”

“Then the trustee will move me,” I said. “And all the locks you changed without telling me will be changed back.”

He didn’t ask how I knew about the locks. Men like Andrew assume the things they do without witnesses cannot be seen.

I handed the envelope to Jessica. “I love you,” I said. It surprised her. It surprised me a little, too. “Which is why I’m doing this like a grown-up.”

I walked back down the steps, past the hydrangeas that needed pruning and the porch mat that read WELCOME with a lie in the O, and I got into Lydia’s car. I didn’t look back. Some scenes only get worse when you watch them twice.

Elaine’s pot roast was the sort of generous that makes you cry if you’re not careful, so I took small bites and made jokes about kindergarten glue sticks and adult men who confuse charm with character. George’s grandchildren had left a Lego fire truck on the end table; I parked it by my water glass and moved it when I needed to sip, like a tiny, red sentry.

After dinner, George reviewed the next steps. “The recorder stamped the memorandum at 4:52,” he said, tapping his watch. “There’s a copy in your bag. That means that even if someone were foolish enough to try to encumber the property tomorrow, they’ll trip over us first.”

“Do you think Andrew is the kind of foolish who encumbers?”

“I think he is the kind of foolish who believes rules are for other people,” George said. “Which is why we bring rules.”

He checked a text. “Company counsel sent Andrew the board letter at 5:18. He’ll read it before bed. Or he’ll ignore it and find out in the morning that ignoring a letter doesn’t stop it from existing.”

“Jess?” I asked.

“A different letter for her,” George said, voice gentler. “It explains suspension without meanness and lays out a path back: compliance, counseling, and a conversation—just the three of us, at my office—with no Andrew. I will shovel a road back for your daughter, but she’s going to have to walk.”

I nodded. That was the right sentence. My chest ached—not from the pneumonia, though that nagged—but from the part of me that had wanted the house gift to be a love letter, not a leash.

Elaine packed leftovers into containers like a general laying out supplies and pressed a heating pad into my hands. “I know you have one,” she said, “but this one is prettier.” It was floral. I hugged it to my ribcage like a pet.

That night I slept in Lydia’s guest room under a quilt she’d made from her late husband’s shirts, small plaids that told stories if you looked. I woke up twice coughing, once from a dream where Daniel was standing in the garage holding that carved duck, saying, “Why are you apologizing to the cold?”

I answered him out loud in the dark. “I’m not anymore.”

The morning bloomed like a schedule. At 8:45, a white van with Coastal Comfort HVAC pulled into the driveway. At 9:05, a locksmith named Angel knocked on the door with a clipboard and a box of brushed-nickel deadbolts. At 9:12, a process server—a nice woman in a blazer the color of calm—left a copy of the trust notice on the porch table with a photo of it there on her phone. At 10:00, George arrived with a folder and a face made of law.

Andrew opened the door wearing a sweater the color of respectable oatmeal and the eyes of a man who hadn’t slept. He looked from the locksmith to George to me.

“This is unnecessary,” he said again.

“Then it will be quick,” George said, and his voice had the exact amount of mercy a courthouse hallway allows. “Eleanor, would you like to show me the guest suite?”

I led the procession down the hall. The room smelled like hairspray and ambition. The ring light stood like an accusation in the corner. The bed was made with the good blanket—the one that had disappeared—folded at the bottom like a trophy. The vent whistled faintly; someone had shut it halfway.

Angel crouched, popped the vent, and frowned. “It’s stuffed with a towel,” he said, waggling the offending terry cloth.

Jessica’s hand flew to her mouth. “I—” She shot a look at Andrew. “We—”

Andrew’s face remained smooth. “It must have fallen.”

Angel looked at the vent opening—three feet higher than a fall could carry. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t have to. He handed me the towel. I didn’t take it.

“Open all the vents,” George said to the HVAC tech. “Full check on the system. Replace the filter. The trust will pay.”

He turned to Jessica. “We’re not here to humiliate you,” he said. “We’re here to fix it.”

Jessica’s eyes filled. “I didn’t—” She broke off.

George softened a notch. “You went along with a narrative that was convenient,” he said quietly. “Now you’re going to choose one that’s decent.”

He turned back to business. “Mr. Reynolds, you’ve received a letter regarding your role at Meyers & Summers.”

Andrew’s jaw ticked. “I received a letter full of insinuations.”

“It contains invitations,” George said. “To resign gracefully and exit with a check. Or to force a vote you will not win.”

“Those are threats.”

“Those are options,” George said. “I’m a boring man, Andrew. I like options.”

Andrew looked past us into the yard, then at the ceiling, then at the vent Angel was reattaching. He was a man counting doors and realizing none of them led to a room where he was the only person who existed.

“You can’t just move in here,” he said to me, last attempt.

I tilted my head toward the papers in George’s hand. “I can,” I said. “And I will. And for what it’s worth, I don’t want to. I want to live in a world where I don’t need to recite clauses to my child.”

Jessica’s shoulders crumpled. She sat on the edge of the bed—my bed—and cried into her hands in the way you do when the picture you’ve been carefully coloring goes off the line and you suddenly see the line for what it is.

I sat next to her. “You do not have to choose him,” I said, and realized while I said it that I didn’t just mean Andrew. I meant the version of herself that had learned to make promises with asterisks.

She nodded into her palms and then stood, wiping her face. “Mom,” she said, voice small. “Do you want tea?”

“Yes,” I said. “And your father’s mug. The blue one.”

She went. I watched her go, and for the first time in months, I didn’t feel like I had left the room by existing.

George cleared his throat. “The trustee hereby restores the guest suite to the life tenant,” he said, which was legal for “Welcome home.”

Angel handed me a key, new and warm from his palm. It felt like a sentence finishing correctly.

Andrew lingered in the doorway. “You’re overreaching,” he said because he needed a word that let him believe he could still be in charge.

This time it was my turn to smile. “You’re underestimating,” I said, and held up my phone. “And I still have one call left to make.”

His lip curled. “To who? The sheriff?”

“To you,” I said, and thumbed a contact starred ten years ago: Daniel. The number forwarded to George’s special line now, and when it clicked, I said, “George? Go ahead.”

George’s other phone buzzed. He answered like a man ordering a sandwich. “Yes,” he said, listening. “Thank you. That was quick.”

He ended the call. “The board accepted your resignation, Andrew,” he said. “Unanimous. The buyout offer is valid until close of business tomorrow. After that, we’ll proceed under the clause.”

Andrew swallowed. “You can’t pin your family drama on my career.”

“You did that,” George said evenly. “With a towel in a vent.”

Andrew’s eyes flashed. “This is absurd.” He turned to Jessica, in the doorway with a mug in each hand, face still damp. “Say something.”

Jessica looked at him, then at me. She handed me the blue mug. She handed him nothing.

“Don’t do this,” he hissed. For a second, the mask slid. What looked out from behind it was not optics.

Jessica didn’t step back. “I can’t unknot myself for you anymore,” she said, and I saw Daniel in her mouth when she said it. “I have to be my mother’s daughter before I am your wife.”

Andrew stared. His math stopped making sense. He left the doorway without slamming anything, which somehow made it louder.

George slipped a card onto the dresser. “Ms. Reynolds,” he said to Jessica, because sometimes a title is a buoy you can choose to hold or not. “Counseling. Boundary work. Logistics. Call me when you’re ready to talk about returning your interest to good standing.”

Jessica nodded without moving her head.

Lydia texted me from the driveway: If he needs to tantrum, he’s welcome to do it at my property line. I have a hose.

I smiled. “Thank you,” I texted back. “We’re okay.”

It wasn’t a lie, not exactly. It was a forecast. The kind of weather you get after a storm when the air smells almost edible and you think—if you’re the kind of person who thinks about these things—that you might be able to grow something again.

That night I slept in the guest suite. The heat came on with a gentle sigh. I set the carved duck on the nightstand and my inhaler on top of a paperback. I fell asleep with the door locked and my phone on the charger and a note on the dresser in my own handwriting: You are not apologizing to the cold anymore.

In the morning, I found Andrew in the kitchen with a single suitcase. He wore the look of a man who wants you to ask him to stay. I didn’t.

He gestured at the coffee machine—which, ironically, I had bought. “Do you know how to—”

“You push brew, Andrew,” I said.

He made a show of chuckling. “I mean… I’ll be at a hotel.”

“Good luck,” I said.

He hovered. “You should consider…” He trailed off. You could see him trying to find a word that didn’t sound like a command and couldn’t find it.

“Lowering my standards?” I supplied. “No.”

He took the suitcase and left. Not with a bang. With a door that didn’t slam because Lydia was outside with her hose.

Jessica came down ten minutes later with hair unbrushed and a paper grocery bag filled with items from the garage: my old wool blanket; the photo of Daniel and me under the arbor; the mason jar of screws that didn’t match anything anymore. She set the bag on the counter like an offering.

“I found your red cardigan,” she whispered, as if the sweater could hear.

“Put it in the drawer,” I said. “Please.”

She did. Then she sat at the table and cried again, a different cry this time. Loss without bargaining.

“We can fix this,” I said. “Not in a week. But we can.”

She nodded. “I’ll call the counselor George recommended.”

“Today,” I said, because some sentences want to be firm.

“Today,” she repeated.

We drank tea at the table where Daniel and I had planned how to protect whatever decency was left in our family once shiny people got their hands on it. The steam made little clouds between us. They were the kind of clouds that release rain you can stand in.

I slept with the window cracked that night and didn’t cough once. The heater hummed. The house settled. Somewhere, a towel was no longer in a vent.

I knew it wasn’t over. But the part of the story where I apologized to the cold was done.

Part Two

Three days into warm air and adult conversations, my phone pinged with a message from an unknown number: Reynolds & Co. has filed for dissolution. The text was followed by a call from a local reporter fishing for comment. I didn’t answer. Instead, I set my phone down on the kitchen table and brewed tea in two mugs: blue for me, chipped white for the person who would need it.

Jessica came down the stairs slowly. She’d been staying in the room that used to be hers in high school, the one with the leaf decals still on the wall in a pattern that pretended to be trees if you squinted.

“I talked to the counselor,” she said, sliding into the chair across from me. Her eyes were swollen from doing something hard. “Her name’s Althea. She’s firm.”

“Good,” I said.

“She asked me when I started believing that keeping things smooth was the same as keeping people safe.”

“And?”

“Seventh grade,” Jessica said without smiling. “Dad lost a bid on a project, and you and he argued about refinancing. I remember standing in the hall, deciding I could make it go away by being pleasant.”

I winced. Not at the memory—we had fought, yes, because fear hates company—but at the way a child’s solution sticks long after the problem does not. “I’m sorry,” I said.

“I know,” she replied, and then—because she was doing the work she said she would do—added, “And I’m responsible for what I did with that belief.”

We drank our tea facing the window. The hydrangeas needed pruning. The world went on needing small, ordinary tasks, which was a relief.

At 10:30, George arrived with Althea—a tall woman with a kind frown and the gait of someone who had walked a lot of people across stubborn bridges.

“Crisis meetings are good at making people sprint,” she said when we sat in the living room. “Today is not a sprint. It’s a beginning.”

Jessica nodded. She kept nodding as Althea outlined a plan: weekly counseling; a temporary separation from Andrew while Jessica worked with her; a financial coach to disentangle dependency; a repair process with me that had nonnegotiable statements in it—this happened, it was wrong, I will not do that again—instead of vague confessions that make the speaker feel better but leave the listener holding fog.

“I can do that,” Jessica said. “I will do that.”

“Good,” Althea said. “Now the hard part.”

She turned to me. “Eleanor, you need a boundary so clear it can be understood from outer space.”

“I thought I had one,” I said. “A legal one.”

“Legal is a fence,” Althea said. “You also need a sign. One sentence. Repeatable. Say it enough that you believe it on your worst day.”

I looked down at my hands. They were mine again—no tremor, no clench. “I do not trade my safety to keep someone comfortable,” I said, and felt an odd hitch in my breath, as if a shackle clinked to the floor.

“Again,” Althea said.

“I do not trade my safety to keep someone comfortable.”

She nodded. “Good. Now say it to the person who needs to hear it most.”

I turned to Jessica. She didn’t flinch. “I do not trade my safety to keep someone comfortable,” I said. “Not even you.”

Tears slid down Jessica’s face. Not a flood. A release. “I hear you,” she whispered.

George cleared his throat with the theatrical timing of a man switching us from soul work to paperwork so we wouldn’t run away from either. “As trustee,” he said, “I’m restoring your beneficial interest to good standing on a probationary basis, Jess. It requires therapy compliance and contribution to household costs per the covenant. If you step back into the old pattern, I step back in with the trust.”

“I understand,” she said. “Thank you.”

He turned to me. “And I’m adding a practical measure: a property manager on retainer for the trust—weekly check-ins for the next two months. You will not have to argue about air filters or thermostats with anyone. You call Mavis. She handles it.”

“Who is Mavis?” I asked.

“A woman scarier than me,” he said, and for the first time since summer, I laughed without a cough on the end.

Andrew did not enjoy his options and took the one with a check. I know this not because I read gossip but because George informed me with a simple email: Buyout executed. If Andrew wanted to keep the part of himself that only understood money, he would have to do it without Daniel’s company propping up his seat at the table.

He tried to text Jessica the next day. She brought the phone to me without reading it.

“Delete without opening,” Althea had taught her. “Don’t give your nervous system the hit of the old drug.”

She held the phone and stared at the glowing rectangle. “You do it,” she said, and handed it to me like a hot stone. I pressed and held, watched the little trash can icon appear, and sent his message into the ether where unneeded things go to be unremembered.

By the end of the week, Andrew had moved into a furnished apartment near the freeway and posted a photo on social media with the caption New views. New start. The comments made smooth noises. I turned my phone over and went out to the garage with a space heater and a tape measure.

“What on earth are you doing?” Lydia called over the fence.

“Taking back the garage,” I said, and smiled when my breath didn’t cloud.

The dusty workbench still smelled faintly of cedar. The carved duck kept vigil. I ran my hand over the long scar in the tabletop where Daniel had once cut a board an inch too far, and I decided that if anyone was going to own this room’s story, it would be me. I drew squares on a sheet of graph paper with the precise joy of a retired teacher solving a problem in the answer key. Table here. Shelves there. A chair by the window for mornings with a crossword.

“Studio,” Lydia said, leaning on the fence.

“Studio,” I said.

We hauled out the boxes Jessica had stacked—wedding vases from other people’s weddings; old posters from middle-school plays; a box of cords that looked like a basket of snakes. Jessica helped, cheeks pink with work, and asked permission before she touched anything that had been mine long before she moved it.

We hired a contractor—Mavis found him—and he insulated the walls, ran new electric, hung drywall, painted it the color of eggs as if to redeem all the eggs I had nearly frozen. We mounted Daniel’s pegboard again, this time to hold brushes and scissors and the kind of hammer you use to tack wire to the back of a frame.

On the first morning of warm, I moved a chair into the square of light near the side door, set a plant on the workbench, and left the door open to let the air decide if it wanted to come in. The garage had been a place someone stuffed with a towel. Now it was my place.

A week later, a detective from Adult Protective Services called. George had made the report, as required. The detective asked me if I felt safe now; I said yes. She asked me if I wanted to pursue charges; I said no. “But I will testify for someone who needs me to,” I added, because it felt important to say.

“Sometimes sunlight is enough,” she said. “Sometimes consequences make shade that grows better things. Call if you need me.”

Jessica listened from the doorway. “Does this count as consequences?” she asked when I ended the call.

“This,” I said, gesturing around the room, “counts as a choice. For me. Your consequences are your choices lined up in a row, and you walking past the ones that look shiny.”

She nodded, a person learning a new language by immersion.

In January, I started hosting a Tuesday circle in the studio for three women I knew from the community center—two widows and a woman whose son had moved her into a basement “for convenience” until Mavis and I helped her draw a line on paper with a lawyer’s pen. We called it the Porchlight Circle because we left mine on and because the word felt like a promise that no one would be asked to do their hardest thing in the dark.

We drank tea. We shared names of plumbers who returned calls. We taught each other how to use the “location sharing” function on our phones without feeling like spies. When it snowed, we put our mugs on the heater and wrote letters to our younger selves, the ones who believed their comfort could be traded to keep someone else from making a face.

George stopped by once, sheepish with a tin of cookies from Elaine. “I am here to return a dish,” he said, holding a plate like a student requests permission to enter a classroom late.

“Leave it by the duck,” I said. “And take a brownie. They’re Lydia’s and I’m not allowed to keep them in the house unsupervised.”

He smiled, looked around the studio, and nodded to himself like a man who has a drawer full of documents but knows some victories do not fit in a file.

“How’s Jess?” he asked.

“She’s building a new muscle,” I said. “It’s sore.”

He nodded. “Good soreness.”

“Andrew?” I asked, though I hadn’t noticed the absence of his updates until that moment and I liked that.

“A consulting job in another city,” he said. “More optics. Fewer elderly mothers making inconvenient choices.”

I let the news sit on the workbench. “May he have to use the good towel sometimes,” I said.

We both laughed. It was a small, mean wish, and it felt cleaner because it was only a wish. The bigger wish I kept for myself: that the people in my kitchen would say what was true before the house had to say it for them.

Spring brought blooms that looked like apologies. The hydrangeas woke confused and then exuberant, the pruned parts growing back with better manners. I kept a pair of clippers by the front door and trimmed without mercy and with love.

Jessica came to Tuesday circle once and then again and then regularly. She listened more than she talked. When she did speak, it was to say sentences in the shape of responsibility. “I shut off the vent,” she admitted one afternoon, voice steady. “I told myself it was temporary. I told myself Mom liked the cold. I told myself I’d make it up to her in the spring.” She let the words hang there. No excuses, no softening. “I’m not telling myself those stories anymore.”

We passed her a cookie and no one attempted absolution.

On Mother’s Day, she made me breakfast and presented me with an envelope that contained a printout from her bank: AUTOPAY—ELECTRIC—$100 from J. Reynolds and AUTOPAY—GAS—$100 from J. Reynolds. A practical bouquet.

“It’s the covenant,” she said, and when she said it she didn’t look at George’s folder but at my face. “And also: it’s right.”

I taped the printout to the inside of a cabinet door. Not where company could see it. Where I could.

In June, the trust’s probationary period ended. George and I met Jessica at his office. He wore his Friday tie—the one with small fish; Elaine had once whispered to me in a grocery store, “He thinks it says he’s fun.” He slid a single-page letter across the table to Jessica. Beneficial interest restored—conditions met. Jessica folded the letter and put it in her purse. She didn’t post a photo about it anywhere. That felt like growth I could weigh.

“Your father would be proud,” George said when we were alone. “Not because you won. Because you kept the part of yourself he liked best.”

“Which part?” I asked, and held my breath like the answer mattered.

“The part that believes in people and in consequences,” he said. “Not as a pair of enemies, but as a pair of handrails.”

I exhaled. “I have another plan,” I said, and slid a sheet of paper across his desk. He read, eyebrows going up.

“The Porchlight Fund?” he said.

I nodded. “A line in the trust’s distributions. Small grants to seniors who need a thermostat, a heater, a lawyer to file a right-of-occupancy, a locksmith who doesn’t ask too many questions about why a lady is changing her locks today and not yesterday.”

George’s eyes softened. “We can build that,” he said.

“And a clause,” I added, tapping the paper. “That the person getting help writes a letter to the next person. Not money. Words. So they remember what it felt like to ask and to receive.”

“Letters are cheaper than lawyers,” George said, and then, because he is a lawyer, added, “And they last longer.”

We filed the amendment. We opened a small account. Lydia brought brownies to the first grant check presentation. Mavis cried exactly once and then didn’t cry again.

On the anniversary of Daniel’s death, I took the carved duck to his headstone. I set it on the grass and told him the whole story with none of the parts blurred. The wind moved across the cemetery like an enormous hand smoothing a blanket.

“George executed the contingency,” I said. “Your optician of optics resigned. Your daughter remembered she was my daughter before she was anyone else’s anything. The garage is warm. The towel is in the rag bin where it belongs. The hydrangeas learned a little humility.”

I felt ridiculous and then not. Grief changes grammar; it lets you talk to people in the present who are not.

When I turned to leave, a young man two stones over was talking to his phone as if into someone’s ear—a father, a brother, a friend. We were ridiculous together. It made it less lonely.

I went home and made toast and honey and ate it at the workbench in the studio while the sun pulled across the floor like a full-length exhale.

Jessica came by in the afternoon with a plastic tote labeled WINTER and the old red cardigan folded on top. She held it up. “Do you want to keep this in your closet or the cedar chest?”

“Closet,” I said. “Within reach.”

She hung it carefully, closed the door, and turned back. “Althea says I have to make amends without asking for a specific response.”

“Althea is correct,” I said. “What are your amends?”

She looked me in the eye. “I named what I did. I paid what I owed. I’m paying forward what I learned. And… I’m moving into an apartment downtown. On my own. For a year.”

I smiled. It was the right size sentence for the moment. “I’ll help you move the boxes,” I said. “And I’ll keep your room ready for Sunday naps.”

She hugged me. Not the desperate grip of December. The steady press of June. “Mom,” she murmured into my shoulder. “Thank you for making the call.”

“You’re welcome,” I said. Then I added, because we say the quiet part out loud now: “And I’m proud of me, too.”

The last time Andrew darkened our doorstep, it was not to demand or charm. It was to return a set of house keys in an envelope that had the decency to be plain. He handed it to me without comment; I accepted it without making a speech. He looked older. Some people are prettier in regret. He wasn’t.

He glanced at the garage. The side door was open. You could see the plant and the chair and the little red fire truck on the shelf that once had been a place for a jam jar of screws.

“Studio?” he asked.

“Studio,” I said.

He nodded once. “Your daughter is… different.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“Better,” he said, surprising me with the right word.

“She’s also the same,” I said. “Just… less edited.”

He tried to smirk; it didn’t fit anymore. “Tell George I took the check.”

“I don’t pass messages through the kitchen,” I said. “You can send him an email.”

He looked like he wanted to say more, and then like he remembered what happens when he says more. He went to his car, drove away at the speed of compliance, and was swallowed by a neighborhood that was now mine again.

I stood on the driveway a minute and let the porch light burn even though it was still light out. The light had nothing to prove. It just did what it did.

A year after the towel came out of the vent, the Porchlight Circle had fifty letters in a box that used to hold holiday lights. We read one at every meeting. Lydia cried occasionally and pretended she had allergies. Mavis ate brownies like a woman carb-loading for a marathon. George showed up once with Elaine and took a photo of the carved duck next to the fire truck and said, “I prefer this centerpiece to the ring light.”

Jessica sat on the edge of the workbench with a mug and told the group about the time she almost said yes to something because she wanted the air to stay smooth and then said no because she wanted to stay honest.

She drove me home from circle that night and stood with me on the porch, both of us quiet in the kind of way that is not absence but fullness.

“Mom,” she said at last, “what would you have done if George didn’t answer?”

I looked at the house, at the hedges properly trimmed, at the door I now locked because I wanted to, not because I had to. “I would have made the next call,” I said. “To the county recorder. To a lawyer. To the neighbor. To anyone who could help me make my one sentence true.”

She smiled. “You only ever needed one.”

“I only ever need one,” I corrected, and flipped the porch light on though night hadn’t fully arrived. “And from now on, I don’t wait until it’s dark to use it.”

We went inside. The house inhaled and exhaled around us.

I slept that night completely through.

In the morning, I made tea, opened the studio, and found a letter slid under the side door in a shaky hand: Thank you for the heater. I didn’t know I was allowed to ask. — M.

I pinned it on the corkboard under the carved duck, made a fresh pot, and set out extra mugs. People would come. They always do, once someone turns the light on and says, clearly, I do not trade my safety to keep someone comfortable.

The garage was my place now. Not because someone banished me there. Because I chose it. Because I chose me.

And because once, when the cold was being cruel and the light in my own house was for other people, I remembered I had one call left to make—and I made it.

END!

News

I Couldn’t Pay My Daughter’s $600 Birthday Bill — Then a Stranger in a Baseball Cap Stood Up. CH2

Birthdays are supposed to be full of joy, but that day, mine was tangled with anxiety. Emma had just turned…

After the acci:dent cost me my leg, my husband left me and chose someone else. With only my sick mother by my side, I worked tirelessly to keep us going. Then a mailman delivered a curious envelope, and what I discovered inside changed my life completely.

Dolores sat in her wheelchair by her mother’s bed, the soft whisper of rain against the windowpane a mournful soundtrack…

My Sister Mocked My ‘Cheap Phone’ — They Laughed Until Her Screen Went Dark. CH2

My Sister Mocked My “Cheap Phone” — They Laughed Until Her Screen Went Dark Part One Madison flicked her wrist…

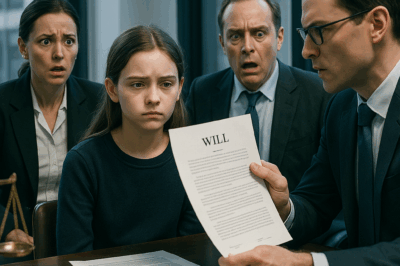

My aunt’s inheritance gave me a house and two million dollars. Out of nowhere, my parents—who hadn’t been in my life for 15 years—appeared at the will reading, saying, “We’re your guardians.” When my lawyer stepped in, their faces drained of color. Ch2

Yesterday, at 28 years old, I became a millionaire. My Aunt Vivien, the woman who raised me, left me everything:…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

My ex-husbamd bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… CH2

My ex-husband bought a condo using my money without asking me. Then, he threatened to divorce me… Part One My…

End of content

No more pages to load