I Found Out My Parents Gave Our Workshop Business To My Younger Brother So I Stopped Working 80…

Part I: South Congress, Cold Clarity

My phone stayed silent for three days, and that silence felt like a rehearsal for the rest of my life. I moved as quietly as I could through the world, like one more local in a city full of transplants, ducking into a small café on South Congress that still smelled like beans roasted in a garage and bread baked by someone who takes butter personally. Outside, Austin was pretending to be breezy. Inside, I was trying to pretend I hadn’t been gutted.

They found me anyway.

My parents didn’t look sad when they pulled up—sad would have implied some loss they were willing to name. They looked inconvenienced. My mother, Susan, had that expression she wore to church and charity galas, a smile ironed flat at the corners. My father, David, had already climbed the ladder of his anger and was standing proudly on the top rung by the time he reached my table. They didn’t sit. They came to deliver.

“Larissa, this has gone on long enough,” he said, voice low enough to bite.

“Jealousy,” he added, as if the word were a diagnosis, and I was the kind of problem you treat with rest and condescension.

The word almost made me laugh. I thought about the Vantage Hotels contract I brought in when we were one payroll from collapse; about the Riverbend collection I designed that saved us two years ago; about the nights I slept under a desk, the mornings I woke up with sawdust in my hair and a new jig sketched in pencil on the back of an invoice. I thought about the five-axis CNC no one else could coax into singing.

“What, exactly,” I asked calmly, “has Ryan done besides spend money?”

My father’s face went the color of kiln brick. He didn’t have an answer, only volume. But my mother—sweet, reasonable, devastating—touched his arm. Her voice softened.

“Larissa, you’ve always been strong,” she told me, like it was a flaw. “You can handle yourself. We never had to worry about you.”

She smiled a sad, disappointed little smile. “Ryan is sensitive. He needs this support. He needs this to build his confidence. Why can’t you just be happy for your brother?”

The air left my lungs. Not because it hurt—the hurt had already done its work—but because the truth in her sentence cracked something final in me. I had mistaken their needs for love. I had spent a decade translating their favoritism as duty. They weren’t rewarding Ryan’s skills; they were rewarding his weakness. And my competence? It wasn’t an asset to them. It was a convenience. It meant I could be ignored, indefinitely.

I stood, lifted my bag, and found a stillness I didn’t know I’d earned.

“I understand now,” I said. “I finally understand.”

I walked past them. My father told me not to walk away. I kept walking. And as the bell above the café door trembled and then settled, my guilt went with it—out, and then gone. If they wanted Ryan to have the company, they could have him. They’d given him the business.

They had given me my freedom.

Later, in the spare room of my friend Emily’s bungalow, the ceiling fan carved the night into pieces while I lay awake and counted the things I had mistaken for love. I realized something else, something colder and more useable: I couldn’t move them with feelings. I couldn’t appeal to a fairness they didn’t value. If I fought, it couldn’t be with pleas. It had to be with proof.

I needed a weapon.

The idea arrived the way good designs always do, as if it had been waiting in the corner for me to notice it. My grandfather. The founder. The man who built our shop with his hands before he let any of us near his machines. He kept a chest in the attic of my parents’ house—sketches, notes, samples, a life’s worth of decisions written in pencil and grit. In the dark quiet of 2 a.m., I drove to the house I had grown up in, the house I no longer recognized.

I parked down the street, used my old key, and slipped in through the side door. Everything smelled like lemon cleaner and curated memory. I climbed to the attic and found the chest under a tarp that used to be blue and now was the color of every forgotten thing. The latch fought me and then surrendered.

Old paper. Wood shavings. The undersong of a life spent making things. A stack of sketches sat next to material swatches clipped with rusted binder clips. Beneath that, a leatherbound journal, dark and smooth, the corners blunted by use. I sat cross-legged on the floor, turned on my phone’s light, and opened it.

His handwriting was quick and sure. He wrote about the first big machine he couldn’t afford and bought anyway. About the maple that warped on a humid August day and how he solved it with a jig he made from scrap. About clients who wanted junk disguised as luxury and how he learned to say no like a craftsman and not a salesman. Then I found a page dated 1991, and the sentence that rearranged my life.

This workshop, he wrote, belongs to the hands that build, not the blood that owns. Skill is the only true legacy. It cannot be given. It can only be earned.

I read it again. And again. He hadn’t just trained me. He had seen me.

I didn’t take the book; I didn’t need to. I photographed every page methodically, every note and sketch and oath he’d made to himself, until my phone was warm in my hands and my heart was colder and more precise than it had been hours ago. This wasn’t about winning an argument around a dinner table. This was about defending a legacy.

When the sun began to move the attic dust, I left.

By nine, I sat across from Emily in her office. She’s a lawyer who can spot a lie the way a woodworker can spot tear-out—by sound, by feel, by what the grain is telling you.

“This is powerful,” she said, tapping the photo of the 1991 entry. “Founder’s intent isn’t a magic wand, but it’s a map. It tells the court where the heart of a business was supposed to be.” She leaned forward. “But intent won’t overturn a signed succession plan. The court knows families are messy. We need two things: proof you were the primary driver of the business’s success, and proof that Ryan is unfit to run it.”

“He’s incompetent,” I said. “He doesn’t know the first thing about the craft.”

“We need more than incompetence,” Emily replied. “We need proof.”

That night, I opened my laptop at her dining table. They’d cut off my company email, but not all my permissions. I had built the company’s financial servers myself. People think passwords are fortresses; they forget doors can be hidden in plain text. The backdoor login still worked.

Expense reports tell stories. The first chapter I opened was labeled “Office Equipment.” Nine thousand five hundred dollars. The invoice said “high-end surround sound system and 80-inch television.” The shipping address was not the workshop. It was Ryan’s apartment.

I stared at the screen for a full minute, not angry—there wasn’t room for that—just stunned by the clumsiness. While I hadn’t drawn a real paycheck in years, he was building a theater.

I kept going. A five-thousand-dollar payment to a law firm I didn’t recognize. “Consulting services,” the line item read. The payee wasn’t the business. It was an LLC: Ryan Designs LLC. I went to the Texas State Business Registry and there it was, filed six months ago. Sole owner and registered agent: Ryan.

Why would he pay his own shell company with family money? I dug into public filings and found the answer that tasted like metal. Three trademark applications, not for his name—for mine. The Riverbend chair. The Monarch desk. The Austin credenza. He was building a life raft out of my work.

He wasn’t just the golden child. He was a thief. And I had the receipts.

Part II: The Things That Hold, The Things That Break

The workshop had always smelled like my grandfather—cedar oil, sweat, an honest day, and the sweet burn of a hand plane earning its keep. He was born in a town where no one ordered anything custom; you made what you needed or you learned to do without. He taught me that wood remembers. You can bend it, steam it, coax it into new shapes, but it’s always telling you where it wants to go. If you listen, you build with it. If you don’t, it breaks.

I thought about that when I set the photo of his 1991 entry on Emily’s desk again. He wasn’t writing about wood. He was writing about us.

Before court, we did the work no one sees. Emily explained the theater of a preliminary hearing: not a trial, but a stage where facts put on their best clothes. She sharpened my story until it could fit into affidavits and exhibits: the Vantage Hotels contract, the Riverbend collection’s awards, the list of clients I’d kept alive with samples and apologies while CNC spindles cooled and restarted.

We drafted a declaration about the CNC I’d coaxed to accuracy out of tolerance. We included emails from clients addressed to me, not the company—praise that had a way of becoming proof. Emily reached out to Rachel, our former shop manager, who wrote a letter with the weight of a person who had watched a decade of sweat become furniture. She described our production timelines, my designs, the difference between my brother’s presentations and the work my hands could prove.

Rachel’s words made me cry in my car and made the judge nod later. There are letters we spend a lifetime earning.

I spent nights continuing to dig. I learned more about Ryan than I had ever wanted to know. The LLC’s registered mailing address matched his apartment. The lawyer retained for the trademarks had emailed him directly about office hours and pricing. The payment to “consulting services” had been wired three days after my mother told me over Sunday dinner that “Ryan has such a vision.” Apparently that vision needed surround sound and an eighty-inch screen.

Emily built a folder that had the weight of a mallet. She labeled it in quiet black letters: Founder’s Intent and Fiduciary Breach. Lawyers like the plain-seeming words that carry heavy stones.

Meanwhile, the neighborhood where I was staying woke with breakfast tacos and dogs on leashes and kids in shorts too long for their age. I ran by the river in the mornings and tried to imagine a life that didn’t braid my worth to a family ledger. Some days, it felt like learning to breathe all over again.

The hearing arrived like weather—inevitable, mixing sunlight with the threat of sudden rain. The courtroom was a dull beige, the carpet the color of resignation. Fluorescent lights hummed like every office that ever refused to tell the truth.

My parents sat behind Ryan, stacked like a family portrait in a magazine that sells a version of “American Living” to people who’ve never had to sweep sawdust out of their shoes. Ryan wore an expensive suit that didn’t understand him and a smile he had practiced for mirrors and donors. He looked bored. Boredom is the luxury of the protected.

When he took the stand, his lawyer fed him words like sugar cubes: vision, synergy, brand alignment, future-facing. He chewed and swallowed and smiled at the judge. He talked about storytelling as if the only story that mattered was the one that happened on Instagram.

Emily stood when it was her turn, not with swagger—she doesn’t do swagger—but with the quiet rhythm of a professional who knows where each tool lives. She started with kindness. Then she began to sand.

“Mr. Ryan,” she asked, “your title at the company is creative director. Is that correct?”

“That’s right,” he said, and the smile tucked itself behind his teeth.

“Excellent. Then you can describe for the court the creative process behind the Riverbend collection—the one that won the Austin Design Award last year.”

He blinked. “It’s a very creative process. A lot of inspiration. We wanted to capture the flow of the river.”

“Inspiration,” Emily nodded, as if the word had measurable dimensions. “And what materials did you select for that collection? Walnut? Maple? White oak?”

“The best ones,” he said. “The highest quality.”

“Specifically,” she asked, voice soft enough to be called polite and sharp enough to cut a rope.

“That’s what our techs are for,” he snapped. “I handle the high-level concepts.”

“The techs,” Emily repeated. “Like your sister, Larissa—the one who actually designed the entire collection.”

His lawyer objected. The judge waved a hand like she was shooing a fly.

“Mr. Ryan, can you tell the court the difference between a mortise and a tenon joint?” Emily asked.

“I don’t build the furniture,” he said, scoffing. “I’m the face of the brand. I’m the one who sells it.”

“So you’re the creative director of a furniture company,” she said, “and you don’t know how to build furniture, can’t explain how it’s joined, and can’t name the wood?”

“I handle the business side,” he said, and you could hear the last inch of his rope fraying.

“Let’s talk about that,” Emily said gently, and picked up the stack of invoices. “Here is an invoice for $9,500 labeled ‘office equipment.’ Can you explain it?”

“New computers,” he said.

“I believe this is a receipt for a home theater system and an 80-inch television,” she said, placing a copy in front of him and one on the projector. “And the shipping address is your private apartment.”

My father went pale. My mother looked confused, like someone had brought her the wrong dessert.

“And this,” Emily continued, putting the next page up, “is a $5,000 payment for ‘consulting services’ to Ryan Designs LLC. That’s your company, registered six months ago. Correct?”

He went white, then gray.

“Finally, these,” she said, and the last pages hit the screen with the weight of a verdict, “are trademark applications for the Riverbend chair, the Monarch desk, and the Austin credenza—designs created by your sister. Why were you attempting to trademark your sister’s designs under your own company?”

The room held its breath. He stammered something about protecting assets. Emily stepped closer.

“Or were you stealing them?”

Silence is loud in rooms like that. It fills the vents, hangs from the fluorescent housings, nestles in the carpet. Ryan looked at his lawyer. He looked at my parents. He looked like a man who had mistaken impunity for immunity and was just now learning the difference.

The judge didn’t take long. She reviewed Emily’s stack, my grandfather’s entry, and the invoices that read like confession. When she spoke, it was with the precision of a person who knows how often she has to repeat herself in this exact room.

“This court finds the plaintiff’s contributions to the business to be overwhelming,” she said, each syllable set square. “The founder’s intent is clear.” She turned to Ryan. “I find a flagrant breach of fiduciary duty—the misuse of company funds—and a fraudulent attempt to trademark company assets through a private LLC.” She turned to my parents, and for a moment, I saw them not as mother and father but as adults who had chosen a story and stuck to it even when it was clearly collapsing. “The current succession plan is invalidated. Given the proven unfitness and breach, and the irreconcilable conflict, I am ordering the company sold at auction. Proceeds will be divided equally between Larissa and Ryan, after repayment of the $9,500 and the $5,000.”

The gavel landed. The story I’d been raised inside buckled. We filed out of the beige room and into a hallway that smelled like stale coffee and last chances. Ryan yelled at his lawyer. My father stared at a spot on the linoleum like there might be an exit in it. My mother stopped inches from me, her breath steady and poisonous.

“You did this,” she said. “You destroyed this family.”

“No,” I said, and my voice was quieter than her anger could find. “You did.”

Part III: What Money Buys, What Work Builds

Six weeks later, the business my grandfather built and my parents misunderstood was sold. After debts and clawbacks, one hundred ten thousand dollars slid into my new bank account. It wasn’t a fortune. It was oxygen.

I didn’t buy a car. I didn’t buy a condo with a pool that reflected a sky full of planes I wasn’t going to take. I rented a dusty two-thousand-square-foot workshop in East Austin that used to be a place where someone repaired motorcycles and feelings. It had a roll-up door that stuck halfway and a concrete floor that had seen worse than me. I hung a simple wooden sign out front, just a piece of oak with letters carved by a hand that wanted to matter.

Legacy Workshop.

I called Rachel. “I can’t match your old salary. Not yet,” I told her. “But I can offer you a percentage.”

“When do I start?” she asked, without performing a speech.

We spent the first weeks coaxing the building back to usefulness. The electrical panel scowled. The dust learned our names. We bought a used CNC and I ran calibrations like prayer, seducing accuracy out of a machine whose pride had been hurt. We tuned the spindle until it sang instead of screamed. The first time it cut without fighting, Rachel threw her hands up like some people do in church.

I called old contacts, swallowing pride where useful and throwing back my shoulders where necessary. Most of my second and third calls went to voicemail. My phone rang before I could make a fourth.

“Larissa,” a familiar voice said. Brian, senior engineer at Vantage Hotels. His tone was warm, almost relieved. “I heard you’re on your own. Thank God. We never liked working with your brother. He kept selling us ‘vibes.’ We’re unhappy with the company that bought your family’s assets. Let’s talk about the new twelve hotels.”

My hands shook after I hung up, but not from fear. Some adrenaline shakes you let happen. They’re part of the body’s way of telling you it still believes in you.

We made a schedule that didn’t worship exhaustion. I had worked eighty-hour weeks for a decade. I had worked through holidays and grief and the small humiliations of being told “you’re so strong” by people who used my strength like a utility. I stopped working eighty for them. I still worked hard. Hard is fine. Hard is honest. But I built boundaries like I build chairs: joinery that lasts, lines that aren’t just pretty but proven.

Rachel and I set up a whiteboard we called The Wall, with deadlines and promises and the little notes that make a day move: call the finisher; order more walnut; bring donuts Friday or mutiny. I made coffee so strong our painter, Marco, asked if I was trying to prime him internally. We kept the music low enough to talk over, loud enough to remind our blood about rhythm.

I went to a liquidation auction wearing jeans and a T-shirt that I’m told makes me look smaller than I am. In the corner, under dust that had the nerve to act like it belonged there, I saw my grandfather’s drafting table. The tilt mechanism was stiff, the pencil ledge scarred, the surface tattooed with the ghost lines of projects that had saved us in decades I was too young to remember.

I bought it. I brought it home. I sanded until the old wood told me it remembered what it had been. I tightened the fixtures like I was securing a patient to the idea of recovery. I rubbed oil in until the grain woke up. And then I put it in the corner with the good light, next to a plant I knew I would try not to kill.

That night, with the CNC humming behind me like a distant highway of purpose, I sat and sharpened a pencil. I pulled out a fresh sheet of paper, and I started to draw. There’s a sensation that comes when lines start to behave—when the arc you imagine feels inevitable on the page, when the dimensions like 17 ⅜ and 24 ½ tuck themselves into a design without fuss. It feels like the noise of a courtroom you didn’t want to be in becoming the silence of a shop you earned.

For the first time in years, I felt calm.

Part IV: The Brother, The Parents, The Work

Ryan sent three text messages and an email with the subject line “We should talk like adults.” I didn’t answer. Adults do not require my attention to exist. The last message was a link to an article about “Taking the High Road,” which I did not click. He posted a photo of himself on social media standing in a coworking space full of glass and succulents, captioned “New venture loading.” The comments were full of people who always like a winner, even when they can’t tell what he’s winning at.

My father mailed me a page from his desk calendar on which he’d written, in blue fountain pen, “I hope you’re happy.” I folded it and used it to level the wobbly table in the break area because sometimes metaphors don’t need to try so hard.

My mother sent no message. She never had to. She lives in my head like an inspector, checking the edges of my work and finding them sharp. It took me a while to realize that her silence wasn’t power; it was absence. In that absence, I made something.

The Vantage contract landed with signatures and appendices and an aggressive timeline. We broke it into chewable pieces. A dozen hotels meant a dozen lobbies, a dozen custom credenzas, a dozen front desks that had to withstand luggage and elbows and the particular violence of keys. I sketched a modular system we could assemble on-site. Rachel sourced lumber; Marco negotiated finishing chemicals like a renaissance apothecary.

We built our first prototype like we were teaching the room a language. There were scrapes, there were mutters; there was a moment where the CNC tried to remind me that ambition without calibration is just a prettier word for chaos. I adjusted, re-zeroed, adjusted again, and the machine settled like a horse offered quiet hands.

At night, I sat at my grandfather’s table and read his journal again. He wrote as much about decisions as he did about dovetails. He wrote “No client is worth a lie,” and “Measure twice, love once,” and “You can’t build something to last if you’re trying to impress a stranger.” He wrote about my mother in the early days—how she laughed when he measured with his hands, how she could find a knot in a board by running her palm along it, how she got busy later and how he missed her handprints on the work.

I thought about showing her those pages. Then I remembered the café and how she had told me I should be happy for a brother who needed help stealing my life. Some doors are worth knocking on. Some aren’t doors anymore; they’re walls made to hold up someone else’s story.

Rachel brought in a portable speaker and a dozen kolaches. Marco told a joke that made Rachel cry-laugh and almost drop a drawer front we had planed to within a whisper of perfect. We stayed late because we wanted to, not because someone mistook our loyalty for an inexhaustible resource.

When prototype one fit together without protesting, I felt a joy that had nothing to prove. We invited the Vantage team to the shop. Brian ran his hand along the grain like a person who knows that finish is a kind of honesty. He nodded, then smiled the rare smile of a man whose job is to be skeptical and who has just been relieved of that duty for a minute.

“This,” he said quietly. “This is why we called you.”

After they left, we high-fived without irony. Then we wrote a list of everything we had learned. The list was longer than the build. That’s how I knew we were going to make it.

On a Tuesday, a thin envelope came from the court: final accounting, disbursements complete. The numbers lined up. The math, for once, felt merciful. I filed it in a cabinet labeled Done, as if anything is.

On a Thursday, I saw my parents in the grocery store, or rather I saw a married couple comparing nectarines with an intensity I recognized. My father’s hair was thinner. My mother’s posture had softened the way wood does when it’s been in the rain too long. I turned down an aisle of dog food and waited until I didn’t have to see them. I felt nothing noble. I felt protective of the life I was building, of the peace I had negotiated with myself.

Ryan’s LLC was dissolved quietly. The trademarks were abandoned. A part of me wanted to frame the official notices. I didn’t. I kept them in a folder at the back of a drawer. Some victories aren’t to display. They’re to lean on when the day tilts.

Part V: The Ending I Chose

We installed the first three Vantage lobby pieces in a heat that made our shirts stick to our backs and our jokes looser. The hotel team clapped in that professional way where they’re happy and also late for a meeting. The second set went smoother. By the third, we had learned which toolboxes to load first, how to talk to the union guys without sounding like tourists, where to park so the elevator didn’t become our enemy.

I took a morning each week to design something that wasn’t on a contract. A chair that celebrates the human habit of leaning back and thinking hard. A desk that invites more than it demands. A credenza that hides a bar because hospitality is sometimes a secret you share with yourself. I started a line I called Riverbend Revisited and wrote a note in the corner of the first page: Don’t chase the old shapes. Let them teach you to find new ones.

Rachel hired an apprentice, Maya, who had arms like she’d carried her life herself and eyes that saw what a joint was trying to do. She and I spent an hour with a piece of white oak that had a mind of its own, learning to listen. Maya told me she used to be a dancer. “Wood is choreography,” she said, and I liked that so much we painted it on the bathroom wall.

We wrote our values on The Wall one Friday just to see if we meant them. Make what lasts. Don’t lie. Don’t work for people who hate themselves. Don’t apologize for knowing how. Don’t pretend not to know. Eat lunch away from the bench. If you’re too tired to be safe, you’re too tired to be useful. Donuts monthly or sooner if morale drops.

In the late afternoons the light came in low across the drafting table and the shavings looked like something that might fly. I sat there one evening with a pencil dull from use and realized I hadn’t thought about the courtroom in days. Not because I’d pushed it away, but because I had built something in front of me that asked for my attention and deserved it.

I took the leather journal from the drawer and opened to 1991. I traced my grandfather’s sentence with a finger that had more scars than it used to.

This workshop belongs to the hands that build, not the blood that owns. Skill is the only true legacy. It cannot be given. It can only be earned.

I wrote beneath it, smaller, my own hand steady. You were right. I’m earning.

A week later, a woman walked into the shop with a cautious face and a tote bag full of brochures. She introduced herself as a designer for a new pediatric clinic. “We want furniture that doesn’t talk down to children,” she said. “Things that are sturdy but kind.”

“Sturdy but kind,” I repeated. “We can do that.”

We sketched. We laughed. She cried once, unexpectedly, when she told me her kid had been in and out of hospitals and how chairs become a kind of prayer in those places. I thought about her words later, alone in the shop. Sturdy but kind might be the entire point.

On a Sunday, when the city tried to be quiet and for once succeeded, I drove to a small cemetery and stood at my grandfather’s stone. I told him everything like he had asked for a report and not an apology. I told him about the judge and the gavel and the drafting table and Rachel and Marco and Maya and the way the CNC had finally decided to listen. I told him about my mother and how she had taught me to make casseroles and cutting remarks, and how I was trying to keep one and unlearn the other. I told him about the letter on my wall and the way it felt to write beneath his handwriting.

“I’m taking care of it,” I said. “Not your name. The thing your hands built. The idea.”

The wind shifted through the oaks like someone agreeing.

I didn’t reconcile with my parents. I didn’t burn bridges. I left them in the state I found them: fragile, load-bearing, prone to weather. Maybe one day, we’ll build a temporary span for a conversation. Maybe we won’t. Either way, I have a shop to open in the morning and a list on The Wall. Either way, I sleep.

On a hot evening in June, we held a small open house. We pushed the machines back, swept the concrete until it stopped arguing, and set out iced tea that melted faster than we could refill. Clients came. Neighbors came. People who had heard a rumor about a woman who left a family business and built something that looked a lot like the truth came. Music from the portable speaker settled into a volume that made room for the sound of stories.

Brian arrived late, straight from the airport, and hugged me like a man who knew better than to pretend not to be grateful. “We just opened the last two hotels,” he said. “Everyone keeps touching the front desks. We installed a thin railing to keep them off. Then we took it down. Let them touch. That’s the point.”

I laughed. “That’s the point.”

Near the end of the night, I found a quiet corner by the drafting table. The room around me glowed with the kind of tired that means you’ve spent yourself on purpose. The sign on the wall—Legacy Workshop—caught the light and reflected it back without bragging.

A message pinged on my phone. An unknown number. For a second, my stomach did the old lurch, the muscle memory of dread.

It was a photo. Of a cheap plywood credenza with bad veneer. The caption read: “I tried to make one of your designs. It’s not good. But my kid loves it. Thanks for posting the measurements. —J.”

I zoomed in. The piece was clumsy, gentle, honest. It was someone’s first attempt at telling their hands a new language. I smiled and typed back: “It’s beautiful because you made it. Sand the edges. Add a strip of hardwood to the front so it takes bumps better. Sturdy but kind.”

The reply came fast: “I don’t know what hardwood is. But I’ll learn.”

I put my phone face down, not to avoid the world, but to keep this moment for myself. The CNC hummed in the back like a cat under a chair. Rachel’s laugh rose and fell in the next room. The drafting table held my latest sketch—a chair that leaned back exactly as far as trust should.

I had spent ten years working eighty hours a week for people who believed love meant using who you could and protecting who you wanted. I had stopped working eighty for them. I was still working hard. But now, when I left the shop at night, the work stayed and the worth came with me.

This is the ending I chose: a shop with a name that tells the truth, a team whose hands I trust, a line of designs that remember where they came from without worshiping it, a life built around craft and boundaries and a journal that says what it means.

The workshop belongs to the hands that build. Mine are not the only hands here anymore, and that is the best part. Skill is the legacy. It isn’t granted like a favor. It’s earned like a day’s pay.

I turn off the lights. I lock the door. The machines cool. The wood keeps its quiet counsel. Tomorrow, the roll-up door will stick halfway and then relent. The first pencil line will find its curve. And I will do what I do now, what I should have been allowed to do all along.

I will build.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option?

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option? Part I: Static Before the…

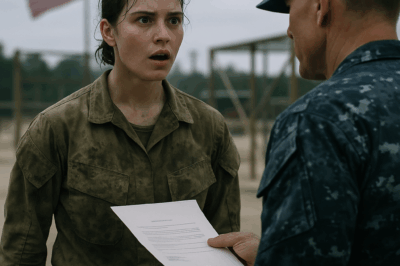

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has… She was just a quiet nurse at…

The Female Sniper SEAL Commander Underestimated — Until She Eliminated 12 Enemies in 5 Minutes

The Female Sniper SEAL Commander Underestimated — Until She Eliminated 12 Enemies in 5 Minutes Part I: Phantom in…

She Couldn’t Pass Basic Training — Until a SEAL Commander Handed Her a Combat Order

She Couldn’t Pass Basic Training — Until a SEAL Commander Handed Her a Combat Order Part I — Orders…

She Was Captured Behind Enemy Territory — Then She Started Eliminating Them One by One

She Was Captured Behind Enemy Territory — Then She Started Eliminating Them One by One Part One The enemy…

End of content

No more pages to load