I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way… my shampoo was running out way too fast! When I started digging, I discovered he was bringing her into our house. But since she liked my shampoo so much, I added a “special mix” to the bottle. The following Saturday, when she got out of the shower and looked in the mirror…

Part One

The first time I noticed the shampoo was light in my hand, I told myself it was nothing. Tiny things change and we adjust—socks vanish in dryers, teaspoons migrate to junk drawers, husbands say they’ll be home by seven and walk in at ten with breath that smells like somebody else’s cigarettes. You choose your battles. You keep the peace. You ignore one purple bottle that feels suspiciously empty.

Two weeks later, I shook the same bottle and it sounded like a maraca.

I stood in the shower holding the thing like it had betrayed me personally. It was an indulgence—a $58 lavender-and-bergamot indulgence I allowed myself, even after fifteen years of marriage to a man who called my self-care “unnecessary expenses” while expensing lunches at places with doormen. I didn’t slather the stuff; I rationed, I savored. And yet the math refused to math. I’d bought the bottle twelve days ago. It should last a month.

I squeezed out the last pearly rope and lathered, staring at the fogging glass as if answers might condense there. Dylan had lost what hair he had by thirty-five and wore what remained in a penitential buzz—this wasn’t him sneaking fancy shampoo in the morning like some guilty pleasure. I thought about the bath bombs I’d been enjoying on Sundays, the ones that had somehow dwindled to two when I knew I’d only used three myself. The hand cream with the silver cap that suddenly wore a new dent I hadn’t made. A hundred tiny changes, all adding up to something that made my throat tight.

“Maybe you’re using more than you think,” Dylan said, not looking up from his phone when I mentioned it over coffee. He wore his charcoal suit, the one with the subtle check he told me was “client-calming.” His keys lay on the counter at an angle that meant stress. “Or maybe one of those bottles has a hairline crack.”

“Maybe,” I said, watching him avoid my eyes. He kissed my cheek—his new habit, small, bland—and said he had to go because there was a “big client meeting,” and anyway, I shouldn’t wait up.

It was the third time that week I shouldn’t wait up.

That night he texted at eleven to say he’d crash at a hotel by the office. Logical. Reasonable. We lived in the suburbs; downtown was thirty-five minutes without traffic, which is to say it was never thirty-five minutes. Logical. Reasonable. The kind of married logic you can tuck under until you can’t.

My sister-in-law April called the next day. She’s seven years younger than Dylan and has a principal’s voice even when she’s laughing. “Brunch Saturday?” she said. “Tell my brother to step away from his spreadsheets and remember he’s married to a woman, not a quarterly report.”

“I’ll try,” I said, my fingers already sticky with the lie that was becoming a second skin. “Or I won’t. Maybe it’s just you and me.”

“Even better,” she said, and we made a plan to meet at a place everyone on Maple Street had an opinion about.

Friday night I set our wedding china on the dining table and opened a Cabernet we used to splurge on without thinking. Dylan arrived at seven with steaks from the butcher and made a show of greeting me like he’d just burst through the door in the third act to choose me and our small life over empire-building. He told a story about an intern who had sent a draft with the wrong client’s name on it. I told one about a web design client who had spelled “entrepreneur” four different ways and insisted the others were wrong. We ate. We laughed. It almost felt like we were us again. When his phone buzzed he lunged. “Work,” he said too quickly when I asked.

Later, at 2:17 a.m., I walked to the kitchen for water and saw his jacket over the arm of the sofa, the inner pocket gaping with a black slab inside. For fifteen years, we had been the couple who knew each other’s passcodes and would never need them. That had been part of the vow built between vows: everything open, nothing locked.

He’d changed his passcode. My birthday didn’t work. Our anniversary failed, too. When I pressed my thumb to the sensor, the screen stayed stubbornly asleep.

I stood there in the light from the stove clock, his phone heavy and dark in my hand, and felt something inside me slide into place like a lock clicking.

In the morning he had replaced the shampoo. A new purple bottle sat in the caddy like a reset button. I took my shower and thought about how resets work. I went to the mall when he left “early for a big pitch” and bought a twin for the bottle. Then I went three doors down and bought something with a little black lens hidden in a ceramic fox meant to hold cotton swabs. On my way home I swung by a tiny beauty supply April had introduced me to and bought a tube of “color-depositing mask” in a shade called Violet Fuchsia and a conditioner marketed to make blondes brighter—which, used on darker hair, will stain like a toddler with a marker. Not harmful. Not permanent. Just…revealing. If someone insisted on using what was mine, they could also enjoy the results of what I chose to buy.

I installed the fox on the shelf facing the shower, queued up the app on my phone, and tested the angle. It pinged in my palm. Motion detected. I saw my own shoulders, my own irritated face as I stepped in and out. The camera went to sleep when I did.

Dylan begged off brunch after an hour. “Work,” he said again, and I watched April watch me watch him go. “You okay?” she asked when the door of the brunch place had finished pinging in his wake.

“I think there’s a leak in the bottle,” I said lightly, and April didn’t kick me for it even though she could have. “Also, come over tomorrow night for whiskey and a bad movie.”

“I knew I kept you in the family for a reason,” she said, but the worry stayed in her eyes.

I didn’t go home after brunch. I went to a coffee shop three blocks from our house and opened my laptop and stared at a blank InDesign document until my phone chirped. Motion detected.

The woman who stepped into my bathroom had hair the color of champagne and legs that made sense of Dylan’s sudden love for hotels. She moved through my space with muscle memory: purse on the vanity, blouse folded on the hamper, hands reaching for my purple bottle like she’d reached for it a hundred times. She was maybe twenty-eight. She washed her hair with my expensive shampoo while humming the Dua Lipa song I’d had in my head the day I’d read our vows. When she was done she wrapped herself in my towel. She used my makeup brushes on my vanity.

I didn’t cry, because I come from people who mow a lawn before addressing the fire. I drove to the scenic overlook where Dylan had proposed thirteen years and some number of disappointments ago and sat on my hood and watched the afternoon fall apart. Then I drove to April’s with my overnight bag and said, “I need to stay,” and she opened the door like she’d been standing behind it for a year waiting.

We watched my bathroom on the laptop like it was a show neither of us had auditioned for. Dylan came in at 3:41 and wrapped his arms around the woman’s waist and kissed her neck while she smiled at him in my mirror. I shut the laptop’s lid and slid it back across April’s dining table and said, “I’m going to hurt her hair,” and April said, “Okay,” and poured two fingers of whiskey into two glasses neither of us had ever put whiskey in.

At the beauty supply the next morning, April held up the box with a bleach-blonde on the front and said, “Are we the baddies?” and I said, “No,” because we weren’t: my “special mix” could be bought at the drugstore by any teenager with twenty bucks and a will to be dramatic. It wasn’t going to burn a scalp. It wasn’t going to cause anything dermatologists couldn’t reverse in a month. It was going to dye whatever it touched a shade social media would have thoughts about.

On Monday I “went to the dentist” for a cleaning at 2 p.m. and parked two blocks away with my phone in my lap. At 2:15 a silver convertible purred into the driveway and Blonde Champagne walked into my home with the key Dylan had given her and proceeded to use my purple bottle with my “improvements” inside.

At 9:04 the next morning, my bathroom camera caught Dylan with his phone wedged to his shoulder saying, “You’re overreacting,” and then, a moment later, “Okay, okay, I’m coming,” and then he left so quickly he forgot his watch on the dresser. At noon April texted: OMFG. Saw Her leaving Meridian Dermatology in a hat.

“Poetic,” I typed back, and then I put the ceramic fox camera to sleep, because watching a girl cry was never going to be my kink.

That night Dylan came home smelling like hospital soap. “Tough day,” he said, and I said, “Must be,” and we ate chicken with lemon and capers like people in a magazine who were pretending to be us. He tried to initiate sex and I said I had a headache and he looked wounded and for the first time in months the wound didn’t pierce me.

At 1:12 a.m., when his breath was heavy and regular, I pressed his thumb to his phone and read weeks of messages with a woman saved under “BM Photography” that included a picture of my shampoo and the caption LOL it’s actually amazing and a line that made me sit down on the edge of the bed because my legs didn’t trust the floor anymore: She’s too dumb to notice anyway. I scrolled until I found the message from the afternoon: She’s back home. All good. Dentist tomorrow. 2 p.m. and the reply: Perfect. Miss you. Last night was amazing. I put the phone back exactly where it had been and lay awake next to a man I didn’t know, planning the rest of my life.

On Sunday evening I wheeled my overnight bag into our house and set it with theatrical deliberation against the door. “How was the lake house?” Dylan called from the couch.

“There is no lake house,” I said, and he turned to look and couldn’t stop looking because my face had a new shape. “April doesn’t have one. I was at April’s house. Watching you on a camera you didn’t know existed. Watching your girlfriend in my shower. Watching her use my things. Watching you.”

He said the script men say when they are caught and have nothing to offer but air: I can explain. I said, “You can collect a bag. The rest you can pick up when my lawyer calls.” He said, We can fix this. I said, “We can divide assets.” He said, It meant nothing. I said, “It meant hours in my bed and the end of our marriage.”

On his way out with his suitcase, he turned and said, without irony, “Her hair… what happened?” and I said, “Some products are not for everyone,” and closed the door gently like I was putting a baby down.

In the morning I called a divorce attorney who had once been my friend in college and now knew more about hidden accounts than Dylan did. I moved money into spaces where Dylan hadn’t learned the passcodes. I sold the house with the pharmacy-smelling bathroom and the bed I no longer had nightmares in because I no longer slept there. I bought a cottage with a porch swing and a kitchen with light in it.

And then I did something I had left on a list in my head for ten years and always said was impractical. I put my name on the lease to a storefront with big front windows and a small kitchen and a stubbornly cheerful sign that read Sweet Beginnings.

I baked. And I began.

Part Two

You think the beginning is the day you sign the papers dissolving a marriage in a courtroom that smells like old paper and boiled coffee. You think it’s the moment you return the keys to a house that was never quite as much yours as the deed said. You think it is the day you hang a “Now Open” sign on glass that your friends have cleaned with vinegar until it squeaks.

You learn, when you have time and distance, that beginnings sprawl. They wedge themselves between moments you thought were endings and make themselves at home.

Six months after Dylan wheeled a suitcase down our front steps, I stood behind the counter of Sweet Beginnings with butter in my hair and a wedding cake order pinned to the corkboard and a line of people that made me hope I’d hired enough help. I had two employees then—Megan with a piping bag that moved like a fountain pen, and Ro with forearms strong enough to carry four sheet pans at once and a laugh that made strangers keep talking. April stopped by before school, her principal’s lanyard slung around her neck and her coffee in the mug with the fox that matched the camera I had retired to a drawer.

“You look like success smells,” she announced, which is a sentence only a sister says with a straight face.

“I smell like vanilla and work,” I said. “You look like discipline and glitter glue.”

She leaned on the counter. “How are you?”

“Good,” I said, and then realized I meant it, and added, softer, “Good.”

Dylan and I had finalized the divorce two months earlier. He’d tried a few standard tricks—I have a separate account because of a bonus; those were business dinners; my friend’s cabin receipt must have accidentally gone on my card. It turned out years of running household spreadsheets for a man who called budgets a mood killer had trained me for forensics. My attorney, Robert, smiled his tired lawyer smile and said, “You’re the kind of client we wish we always had—organized and angry at the right things.”

We divided what there was to divide. I gave him the espresso machine he’d bragged about to clients and the set of knives we’d gotten for our wedding because I preferred the weight of different blades. He gave me back the passcodes he remembered hours too late. He did not get the house; he could not afford the mortgage without me, and I had no interest in sleeping where he’d been someone else’s hero. We sold it and cut the check along the line the court drew.

Brittany—her last name was McAllister, a detail that had felt important and then, with time, had become simply true—disappeared from my life after that Saturday with the silver car and the hat. She disappeared from Dylan’s two weeks later, April reported gleefully over tacos. “She has taste in men after all,” she said, and we raised our margaritas to the toast to hair that grows back and lessons that stick.

For a while I followed their lives the way you check the weather in a city you once lived in. The aunt of one of April’s teachers had a cousin who worked at Dylan’s firm and reported that he’d moved through three jobs in a year, spectacular in interviews and less so when asked to do the thing after the talk. A mutual friend told me he started dating a woman who wore red lipstick like armor. I wished her patience; then I wished her sense.

Some nights, in the cottage I had painted a shade of white that implied money and space while costing less than a weekend at a hotel, I sat on the porch swing and let the quiet settle around me. My hands ached in a way that meant I’d done something worth aching for. Sometimes I pictured the bathroom with the purple bottle and felt a small tightness, like a scar stretching when you reach too high. Mostly I felt nothing. Indifference, I discovered, is a warm coat.

Then, on a Wednesday morning when the air came down the street like a river and the sun slid in stripes across the bakery floor, the bell over the door tinkled before our “Open” sign flipped, and Megan came back into the kitchen and mouthed oh my god.

I stepped into the front and saw the ghost from my phone become a person in my doorway. Brittany stood with a bob that was too severe for her features and sunglasses pushed up onto her head like a crown too heavy to wear. She held her purse with both hands the way you hold a cat that might run.

“Christine,” she said, and I heard the way my name hit her teeth like a foreign word. “May I…?”

“Sure,” I said, because I had decided long ago that I would be the kind of person I liked in stories. “Coffee?”

She nodded. We sat at a small table tucked into the corner. Megan pretended to clean the same spot on the glass case for a full minute before the universe reminded her that croissants burn while you eavesdrop.

“I owe you an apology,” Brittany said, and it had the shape of a sentence she had practiced. She took a breath and the practiced shape fell off. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry I was in your house. I’m sorry I used your things. I’m sorry I let him convince me you were…something you weren’t. I’m sorry I made you the punchline.”

I watched her face. The last time I had seen it, it had been in a screen, smooth and cruel and laughing at the dummy. Now it looked like a person’s face.

“I did a lot of therapy,” she added when I didn’t answer right away, and the corner of my mouth tugged. “Part of it was making amends where possible. You were… the list had your name in bold.”

“What happened after?” I asked. “Your hair…?”

She laughed, and it was a real laugh, tinny and painful, but honest. “I cried for a week,” she said. “Then I bought hats. Then I realized that if my entire career could be taken by a bottle of shampoo, maybe I needed another career.”

“What did you choose?”

“Photography,” she said, and her hand moved in the air like someone framing a shot. “Behind the camera. It’s quieter there. Harder work. More satisfying. I feel…” She looked for the word. “Useful.”

April came in as Brittany was leaving because the universe likes timing. She stopped, looked at me, looked at Brittany, looked back. “Am I about to witness a hug or a homicide?”

“Neither,” I said. “We’re practicing being complicated.”

Brittany smiled, and there was gratitude in it. “Your shop is beautiful,” she said. “You are, too,” and then she left, and the bell over the door laughed behind her.

April sat. “You couldn’t pay me enough to be that gracious,” she said. “And I say that as a public school principal.”

“I didn’t do it for her,” I said. “I did it because carrying anger takes both hands, and I need mine for piping bags.”

We laughed, and when the laughter slid into the warm place where serious lives, she said, “He filed for bankruptcy last week.”

“I know,” I said. “It was on the county site this morning under ‘new filings.’”

“Do you ever wonder…?” She let it trail off because she knows me.

“About what?”

“If he sits somewhere and thinks about the purple bottle and the fox camera and you,” she said. “If he knows he made a mistake larger than his vanity.”

“I don’t,” I said, and meant it. “I think about butter temperatures and yeast and whether I want to teach a class at the community college in the evening. I think about my second location and who I want to hire. I think about what book to read. I leave him to his own thoughts. We deserve separate living rooms in our heads.”

She reached across the table and squeezed my hand. “You built a life that didn’t need him.”

“I built a life that doesn’t center someone else’s needs,” I corrected gently. “Which is not the same as building a life alone.”

Some Saturdays I closed the shop at three and took the train into the city to meet a man who owned a landscape architecture firm and understood mornings. Sometimes we sat on benches and did not speak for long stretches and I loved that about him. He asked about my cakes the way people ask about children. I asked about his trees. We had agreed to keep meeting while it kept feeling like ease.

In the spring the culinary department at the community college called and asked if I would like to teach “Introduction to Professional Baking” on Tuesday nights. The first class I held up a whisk and said, “Emulsify,” and a boy in the back wrote it down like it was math, and I remembered the way my grandmother had made biscuits without measuring anything but water by the way it sounded hitting the bowl, and I said, “Sometimes you need a number, sometimes you need an ear,” and they looked at me like I might be interesting, and I felt lucky in a way that had nothing to do with men or betrayal.

People asked sometimes about the story of Sweet Beginnings, because stories sell sugar. I’d tell them the commercial version: I’d always loved baking but kept it a hobby until life gave me a nudge. I didn’t talk about purple bottles or hospitals. I didn’t talk about cameras. I didn’t talk about the fact that I knew the laws in my state about marital property like I knew the ratios for pâte à choux. If someone pressed, I’d say, “I chose myself,” and they would nod, because everyone likes to believe you can do that and it will go well. Sometimes it does.

On the anniversary of the day I had stood in my shower holding an empty bottle and a fistful of hurt, April and I locked the door to the shop at noon and took two slices of vanilla almond cake to the park. We ate with plastic forks because I’d forgotten spoons. A little girl with pigtails walked by with a balloon and said, “Are you birthday?” and April said, “We are,” and the girl’s mother smiled at us and there was no shadow in it.

After, we walked past the storefront with the “For Lease” sign I’d been courting. I put my hand against the glass and tried to see the space filled with ovens and laughter and a list of orders tacked to a corkboard. “You’re going to do it,” April said. “You’re going to live your life while it’s happening.”

“Planning to,” I said. “Sustained release.”

“What?”

“Like sugar,” I said, and we laughed and she shook her head and said I was insufferable and she was right in the best way.

If the universe insists on punchlines, sometimes it delivers them kindly. Six months after Brittany came into my shop and drank my coffee and left with her head held a little different, a woman with red hair walked in wearing a hat that made April elbow me where I stood behind the case. The redhead ordered two eclairs and a coffee and paid with a credit card with a name that wasn’t Dylan’s. When she left, April raised an eyebrow and I said, “We don’t root against the next cast,” and she said, “You’re sentimental,” and I said, “No, I’m busy,” and went to pull a pan from the oven while the timer sang.

In my cottage a fox camera lived in the back of a drawer where it couldn’t see anything. In my shower sat a drugstore bottle of shampoo I loved because it didn’t claim to fix me. My vanity held makeup brushes that belonged only to my face. My phone lay on my nightstand and no one lunged when it buzzed.

If you came all this way for revenge, maybe you wanted more fireworks. Maybe you wanted me to cut the sleeves off his suits or hand his mistress a bill for towel use. I will tell you a secret the day you realize you deserve better than a man with locked passcodes is better than any explosion. The day you trust yourself to leave quietly and build loudly is the day the story belongs to you again.

Sometimes I hear the sentence in my head like a line of code that started the program: I found out my husband had a mistress because my shampoo was running out too fast. It makes me laugh now, big, breath-stealing laughter in my kitchen when Megan is trying to balance a tray and Ro is yelling that the delivery guy is early again. The bottle was lighter. I am not.

On the night of our little anniversary, I took a bath in water that smelled like eucalyptus and closed my eyes and remembered nothing sharp. The porch swing sang its hinge-song in the wind. Somewhere, in a bathroom that was not mine, someone was learning the hard way that some products are not for everyone. I wished her well, truly, and then I pulled the plug and watched the water go, and it felt like letting all the things I did not need disappear down a drain I would not mourn.

The best revenge is living well. It is not just a fortune cookie. It is a daily practice: choosing who sits at your table, who knows your passcodes, which bottles you buy, which stories you keep telling your own heart. It is pastry lamination and bank statements and therapy and saying no when someone asks to borrow something you can’t afford to lose.

It is a purple bottle, full. It is a woman who knows exactly how much is in it. It is a life that does not require measuring out forgiveness in teaspoons to people who bring their own spoons and never bring a dish. It is everything you make with flour and fire and a spine.

And if you need something to hold onto, hold onto this: you can be gentle and unbreakable at the same time. You can be a person who bakes beautiful things and refuses to serve yourself up to people who don’t know what that costs. You can begin again. You probably already have.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My daughter-in-law slapped me in the face and demanded my house keys! CH2

My Daughter-in-Law Slapped Me in the Face and Demanded My House Keys! Part One The slap landed before I…

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing. CH2

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing …

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down The Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything. CH2

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything Part One My…

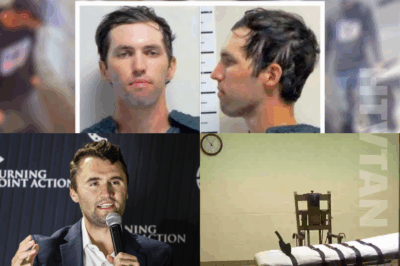

Suspect In Charlie Kirk Killing Could Face The DEATH PENALTY — Utah Signals An AGGRAVATED Murder Case

Prosecutors booked 22-year-old Tyler Robinson on aggravated murder, a charge that opens the door to capital punishment under state law….

“We will find you, we will try you and we will hold you accountable to the furthest extent of the law. And I just want to remind people we still have the death penalty here in the state of Utah.”

Utah Governor Spencer Cox Issues STARK WARNING — State STILL Has The DEATH PENALTY As The Charlie Kirk Case IntensifiesHours…

SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME “YOUR CHILDREN ARE MINE.”

“SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE” MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME—‘YOUR…

End of content

No more pages to load