I Come Back From Afghanistan With One Arm — And My Family Acted Like I Didn’t Exist…

Part One

The first time I saw the missed calls, the number didn’t even look real. Twenty-eight. Every one of them from the same people who’d shrugged me off hours earlier. The monitor beside my hospital bed beeped steadily as if to say, we’re still here, even if they weren’t. Sterile air bit my sinuses. A cuff squeezed my bicep at timed intervals. IV lines trailed from the crook of my elbow in thin, insistent threads.

The screen glowed on the tray table. The family group chat sat open, its bubbles and dates and half-hearted emojis the fossil record of years of low effort. My brother Troy’s two-word dismissal. My parents’ clipped excuse about a barbecue. My own small reply, trained into me like a reflex.

Fine.

Now they wanted to talk. Now that my name had traveled farther than our chat could contain. Now that what they did wasn’t just a quiet absence but a public thing other people could have opinions about.

I turned the phone face-down on my chest and closed my eyes. The energy it would take to answer them, to make them feel better about what they’d chosen, was energy my body did not have.

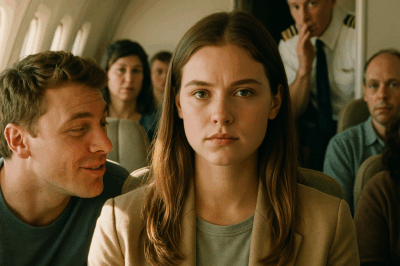

Thirty hours earlier, the story had begun in an uglier yet more ordinary place: baggage claim at Portland International. Roasted coffee from a kiosk drifted into the sharper tang of jet fuel. The belt rattled to life. I braced my legs, shifted the strap of the new prosthetic—skin already raw beneath it—and tried to get comfortable in a harness that wasn’t made for comfort.

Suitcases tumbled out. I saw mine—oversized black with a bright yellow tag. In my unit, James had called it the taxi cab. He’d teased me because he was James and teasing me was one of his ways to keep us human. He didn’t make it home. The thought hit hard and then softened itself the way you do when you’re trying to function in public.

Dragging the taxi cab off the belt with one hand felt like wrestling an alligator in slow motion. I leaned back with everything I had, heels skidding, until the suitcase thudded to the floor. Sweat dampened the collar of my shirt, even with overworked air conditioning blasting through the vents.

I took a breath, pulled out my phone, and tapped to the family thread—the same thread where birthday greetings had turned into strings of champagne emojis, where my updates from Afghanistan went unread until I texted please confirm receipt and my mother replied ok. I typed:

Flight lands at 5:00 p.m. Can someone pick me up?

The typing dots bobbed, then vanished. Minutes later: busy. just grab an uber (Troy). Another: we’ve got a bbq tonight. why didn’t you plan better? (Mom). I stared until the words blur-bled like cheap ink. For months overseas I’d rehearsed a homecoming—awkward sign at the arrivals gate, Dad’s laugh sounding older, Mom’s perfume stronger than I remembered. I had not pictured ride-share and a shrug.

I typed the two letters I could always type in any season. Fine.

Something in me folded inward without fuss. No wrenching. No sob. Just a smaller shape that could be carried without getting in anyone’s way.

The Uber line outside stretched long and jittery. The glass façade threw late sun back into our faces. My body swayed under me—the peculiar sway you get after too much time in a pressurized tube. The driver, a middle-aged man with kind eyes named Paul, hoisted my bag into the trunk without looking at my left side. I sat in the back, pressed my forehead to the cool window, and let the city smear by.

Every bump jarred like an insult thrown at a tender part. The prosthetic chafed against its socket; I shifted it more than it deserved to be shifted. By the time Paul turned down my street, twilight had stretched into the soft dark that makes windows glow like invitations. The neighborhood smelled faintly of charcoal and fat hitting flame. I wondered which porch belonged to my parents.

Inside, the air was stale, edges curled. I had asked them to bump the thermostat the day before. They had forgotten. The mail basket overflowed with unopened envelopes—the ones I had asked Troy to handle. The fridge hummed in the corner like a guilty dog. I opened it out of habit and shut it fast. Condiments lined up like soldiers from a war that had ended before I left, milk two weeks sour, pickles floating in cloudy brine.

I kept my coat zipped and sat on the couch. The silence pushed against me heavier than any gear I’d carried. Just a minute, I told myself, and slept like someone who had been holding herself upright on duty for months and finally found a piece of furniture with no opinion about it.

I woke to the sound of my own breath rasping wrong. The room had shifted; the edges of the dresser wavered as if heat lay between me and wood. A high, insistent chirp arrived and then doubled. The carbon monoxide detector flashed red across the room as if it were doing its personal best to save my life. My phone lay on the coffee table—eight inches farther than my arm could reach even on its best day.

I stretched, fingers brushing air. The couch seemed to grow teeth and drag me backward. My chest rose and fell like someone else’s. One new notification pulsed on the face of the phone, a small glow against the dark. I thought of the word I’d typed at the airport. Fine. I almost laughed. Then the edges of the world went soft and that soft went black.

When I came back, a nurse’s voice slotted into the gap where memory had been: “Easy. You’re in the hospital.” Tape tugged my skin. Light flooded down at me like a fluorescent river. The steady hum of machines braided around voices. Thick throat. Heavy head. My eyes found the tray table as if they had been trained. The phone lit: twenty-eight missed calls, time stamps stacked like a timeline of panic. Troy. Mom. Dad. Over and over, like pounding on a locked door.

I didn’t unlock it. I let the screen go dark and studied the grid of ceiling tiles. My body hurt where it had earned the right to hurt. But the ache that made me turn my head away from the phone was older. I knew its shape already.

Before Afghanistan—before the prosthetic’s strap dug into tender skin, before the news, before the parade of strangers who would learn my name—there were the small moments that trained me in what family was and what it wasn’t.

We lived on Portland’s east side in a pale green two-story that always needed paint. The maple out front flung helicopters across the driveway every spring. We were a three-person orbit organized around my older brother, Troy, the sun. He was three years ahead, star pitcher, golden boy smile. Teachers loved that smile. Cashiers at Fred Meyer noticed him and threw in a pack of gum. My parents circled him like planets—warm and bright when he was near, dimmer when he left the room.

I was the quiet one, the girl with the clarinet and straight A’s and a library job. She doesn’t need much, my mom told people. She said it like a compliment. It was permission to forget.

The maple tree memory sticks because the body always remembers first. I was eight; the bark tore my palms as I scrambled up a branch that wasn’t made for the weight of little girls who keep secrets. It cracked. I fell. The shock screamed through my radius and into my shoulder. The ER smelled like old mints and disinfectant. They confirmed the fracture, wrapped my arm in plaster, and left me with Mrs. Turner from across the street so Troy could get to the championship game on time. “He can’t miss this,” my mom whispered, pushing sweaty hair out of my face like that counted as mercy. “The whole team is counting on him.” The doctor asked if my parents were coming back. “After the game,” I said. It was a lie my mouth told before my brain had time to veto.

High school kept teaching. Troy got new cleats each season and weekend camps across the state we’d never heard of; I covered my own clothes and everything else with library paychecks. On the night I received a statewide essay prize, my parents clapped politely and ducked out before my name was called. Troy had an early practice. I folded the certificate into my backpack with the care you give to fragile things you know won’t be displayed on a fridge.

When the scholarship arrived in the mailbox in the big envelope, my dad’s first question wasn’t congratulations. “This won’t cost us anything, right?” he asked. “Troy’s summer camps aren’t cheap.” I smiled, said what I had been trained to say. No problem. The words didn’t taste like mine.

Recruiters came to campus in stiff uniforms and too-pretty smiles. Something in me leaned toward them. Honor. Order. The chance to belong in a way that didn’t come second. Maybe my dad would respect me in a way he could quantify if I wore the flag on my sleeve. I enlisted. Basic made me run until my lungs learned how to ask for air kindly and push-ups until my arms shook and the drill sergeant’s voice followed me into sleep. It also made me feel useful in a way school never had. My fellows didn’t care about Troy’s curveball or my parents’ schedule. They cared if I could carry the pack and keep my head when the world got loud. Can you cover my flank? Yes. The first family that ever asked me that and meant it wasn’t blood.

Afghanistan was dust ground into seams and boots and teeth. The mountains bit the sky with stone. We ate MREs that tasted like the memory of beef. We played ugly jokes on each other and apologized when one landed wrong. We counted days off the calendar with pen marks that looked like wounds and then like badges. Troy’s notes were one line; my parents’ postcards shorter. Proud of you. Stay safe. We taped them above bunks and called that enough.

The blast didn’t sound like the movies. It sounded like a door slamming in an empty house. The world went white. Pain carved me open and then absence did the rest. When I woke at the field hospital, I stared at the place where my left arm stopped and my brain, so stubborn, kept sending signals anyway. Letters came eventually. We’re glad you’re alive. Get well soon. Troy sent a photo of his new car. Even then I typed, Fine. Some muscles refuse to unlearn themselves quickly.

Coming home, I carried an image of Portland in my head that couldn’t survive the weight of a group chat. That’s the harm of a lifelong habit of minimizing yourself: you believe two letters can protect you from the reality that some people will choose you only when the optics require it.

Michael Chen, a local reporter, came to me by accident. He was shadowing a paramedic for a veterans health story when he overheard break-room talk about a soldier who had texted her family from baggage claim and been told to call a car. He knocked on my hospital door with a press badge and a face that looked like it had been trained to be kind and not just to look it. Would I talk? I wanted to say no. The reflex to protect my family’s image had muscles of its own. But I thought of the 28 missed calls, the sudden need to control the narrative when life had made it messy for them. I thought of how my silence had preserved their standing; how my pain had always dampened itself so the household could sleep.

So I told the story. Not with venom. With detail. The number of hours between Kabul and Oregon. The way the prosthetic strap burned my skin. The exact words from the group chat. The Uber. The couch. The detector. The black.

The ten o’clock news ran it with a title that made me wince and also softened something in me: Veteran Returns from Afghanistan, Left Alone at Airport. They used blurs and B-roll and respectful voice-over. It was enough.

The next morning, my world broke open. Dayton has its own version of this—Portland did, too. Facebook groups for neighborhoods. Nextdoor comments. Hashtags nobody asked permission to invent. My inbox flooded with strangers and neighbors and people I hadn’t seen since band camp. You deserved better. We’ll drive you anywhere. I make casseroles. Don’t argue. A plumbing company offered to fix my house. A hotel chain comped me a room until the repairs finished. A grief support group left a message. My Uber driver, Paul, showed up with a bag of apples because his wife said fruit felt like comfort. He stood in the doorway and shrugged when I tried to thank him enough.

My family did what they always did when their image felt threatened. Troy left voicemails that went from frantic to angry. “You made us look like monsters.” Mom sent paragraphs that read like performances: the barbecue had been planned for a week; Dad’s back had been acting up; why didn’t I plan better? We thought you wanted independence after everything. Dad left a single voicemail. “This has gotten out of hand. Call me so we can fix this.” Fix this. They were right to be afraid. For once I was not going to use my body to absorb the blame.

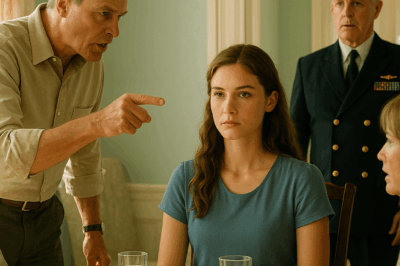

Two days later, they swept into my hospital room with the grocery-store bouquet still in plastic. Mom’s voice pitched high so everyone on the hall might hear. Troy’s jaw clenched like a fist. Dad kept his hands in his jacket pockets and let his eyes land anywhere but my face. The beeping from the monitors filled the moment where codependent habits used to live.

“This is getting blown way out of proportion,” Troy said. My eyebrow lifted on its own. “Is it?”

“You didn’t tell the whole story,” he snapped. “You made it sound like we abandoned you.”

“Because you did,” I said. I didn’t raise my voice. You don’t have to. Volume is not the same thing as power.

Mom tried the line that had worked on me at eight and twelve and twenty: “That’s unfair. You know we had plans. You can’t expect us to cancel every commitment at the last minute.”

“Families do,” I said. “Ours doesn’t.”

A nurse named Jessica stepped in as if she’d been listening at the door and just happened to choose that moment to check vitals. The empathy on her face made me feel steadier. You choose, she’d told me the night before. You choose where you go, who you let in.

“We’ll take her home when she’s discharged,” my mom said to the nurse, eyes wide with polite threat.

“That’s not how this works,” Jessica said without looking away from me. “She decides.”

My mother blanched. That fear wasn’t for me. It was for the façade she’d lacquered for years.

“I’m not going home with you,” I said. The words landed heavy and true.

Mom slammed the flowers down hard enough to crack a stem. “You’re humiliating us.”

“No,” I said. “You did that.”

Troy muttered something and left fast enough that his sneakers squeaked. Mom chased his storm. Dad lingered. For a second, I thought he’d speak. He put his hands deeper in his pockets and left instead. The door clicked. Jessica adjusted my pillow like that could fix what had just been unmade. “That took courage,” she said.

It took exhaustion—even more than courage. Exhaustion has its uses. It keeps you from doing the labor of making other people comfortable.

Discharge came with a binder and bruises and instructions about not being alone for a day or two. My family didn’t take me anywhere. Diane from across the street did. We barely knew each other beyond trash day greetings and nods at the mailbox. She showed up with a tote of snacks and magazines and hand lotion like she’d prepared for this role all her life. “No one should have to do this alone,” she said. And then she proved it.

The hotel room the chain donated smelled like lavender and fresh sheets; the manager pressed the keycard into my palm like he was handing me something sacred. A plumbing company fixed the freeze. A restoration crew installed a new thermostat and didn’t leave until the furnace ran like a heart. The VA scheduled rehab. Carl, my physical therapist, called the mirror our ally and taught me how to buckle a shirt one-handed without swearing out loud. “You’re not broken,” he told me. “You’re adapting.” It’s amazing what people will say to sell you a program. It’s more amazing when it is true.

When I moved back home, the house held me without asking me to be smaller. Diane brought casseroles. Her husband raked my leaves. A retired teacher sat on the porch with me on days when the air felt like too much and let me talk about James, about convoys, about the way some noises feel crowded with meaning. A veterans group invited me to coffee and didn’t flinch when I told the truth in the wrong order.

My family sent a card. Thinking of you. They didn’t mention the hospital. They didn’t say sorry. Troy left one last voicemail complaining about how much grief his coworkers had given him. None of them asked what day release valves squeal on furnaces. None of them learned where the detergent lives in my kitchen. I stopped waiting.

I put my time into something new: a fund for women vets coming home to empty kitchens and cold thermostats and silence where arms should be. We paid for rides and appliances and groceries, the small ordinary things that mean life. I named it for two friends we left in a desert that doesn’t return what it takes. The first meeting was in a VFW hall that smelled like yesterday’s coffee. People who had become family filled folding chairs and left their phones alone. I told them what I’d learned. “This isn’t about pity. It’s about presence. Family is who shows up.”

The applause wasn’t thunder. It didn’t have to be. It was steady and warm—like a circle of arms around my shoulders. The feeling I’d stopped believing in from certain people came back in the faces of strangers who’d chosen me on purpose.

Six months later, my garden came back. Tomato vines climbed greening cages. I pinched a blossom and whispered James’s name into the morning. The house thrummed with heat. The pipes dared the weather to try again. Physical therapy made the prosthetic feel less like an enemy. Some days hurt. Some days didn’t. Tired still came at odd angles. Love did too.

At dusk I sat on my porch with my phone beside me. The support group thread pinged with dumb memes and check-ins and you got this. My family thread pinged with reasoning and explanations and the sort of apologies that start with if. I put the phone down face-up this time. The sky went purple. Crickets stitched an evening together. And I exhaled something I hadn’t realized I’d been holding since before the maple tree.

It turned out my revenge wasn’t loud or cinematic. It was living well. It was saying no to an old pattern and yes to new rooms. It was knowing I’m not a ghost unless I choose to be. It was building a life—messy, chosen, honest—where I didn’t have to type fine to make a household run. Where people hugged as tight as I’d always imagined at an arrivals gate even if that hugging happened in kitchens and VA lobbies and parking lots that smell like rain.

I had found a family and it looked nothing like the one that raised me.

And the best part? I didn’t have to audition to keep my seat at the table.

Part Two

The hotel room had felt like a stopgap, a kind hand offering a warm bed while the house remembered how to be a home. The day I turned the key in my own front door and the furnace answered with a low, satisfied hum, I understood how much work comfort does invisibly. It is a choreography of small things—a thermostat clicking, a neighbor texting I’m at the store, need anything?, the sound of the mail carrier’s steps up your walkway, not because of a bill, but because of a letter. Comfort is the opposite of performance. It keeps you alive without asking you to clap for it.

Diane walked me through the new thermostat like I’d never programmed one. I let her. It’s a delicate thing to accept care from someone who doesn’t owe it. You say thank you and you mean it and you don’t tally mental debts. Some people love a ledger. Diane loves a casserole dish you never quite get back to her because she keeps replacing it with another.

Carl increased the weight I lifted at the VA rehab by the half-pound, like he was sneaking strength into me when I wasn’t looking. He made a face when I swore. He swore when my face made it first. We celebrated stupid victories like rolling a yoga mat one-handed. “This is better than some people do with two,” he said. I laughed the first time. I didn’t the third. I believed him the fifth.

Sundays at the veterans support group, younger women arrived with eyes too sharp and too tired. The fluorescent light of the community center did us no favors. We sat in a circle on plastic chairs. A woman named Shawna could recite the entire VA form for PTSD screenings the way other people recite their kids’ birthdays. She wore a hoodie in July like her bones got cold even when the weather didn’t. When I told the group about the airport and the barbecue and the couch and the detector, the grim smiles told me they knew the script. A woman named Val snorted and said, “My mom said well you know your father isn’t good at emotions. I asked her if maybe he could try picking me up from the airport with a practical emotion.” We laughed and cried and ate donuts as if sugar could plug holes in a sinking ship.

Then one Wednesday, Michael Chen called. He’d kept in touch like a good reporter and a decent human. “We’re doing a follow-up on returning vets,” he said. “There’s a community fundraiser at the VFW. They asked if you’d speak.” My throat did a small, familiar tighten. “I’m not a speech person,” I said.

He reminded me I had already made one. He reminded me of the clapping and the way my shoulders had dropped afterward like heavy gear. He reminded me of the young women who wrote to him after the first story, who had come home to refrigerators as empty as mine. “You don’t have to make it pretty,” he said. “You have to make it true.”

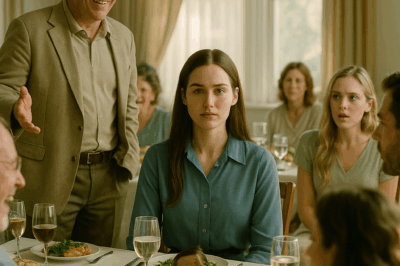

So I did. The VFW smelled like burned coffee and sawdust. The hall filled with faces I recognized and some I didn’t. Mrs. Turner sat in the back with tissues in case I needed one and in case she did. Diane waved like someone who had already put a lasagna in the oven for later. A couple of guys I’d seen three times and barely knew hugged me like we went to kindergarten together. And then I saw them: my parents and Troy, near the back, arms crossed, expressions carved from the same stubborn material as always. I pressed my palms into the sides of the podium and felt the splinters.

“Most of you know the story the news told,” I began. “It wasn’t all of it. Here’s the rest.”

I spoke about the maple tree and the ER, about the graduation I had to congratulate myself for, about the scholarship letter that didn’t earn a cake. I told a town that had stood in line for Troy’s baseball autographs what it feels like to be the kid left with a neighbor at eight, the young woman whose father asks if her education will cost him anything. I didn’t make a case. I drew a map. They followed it. When I got to the airport and the barbecue and the couch and the detector, the sound in the room turned the way sound turns when it decides to protect. Frank stood to object and looked small under a fluorescent fixture older than the dust on the VFW flag.

It wasn’t about humiliating them. It was about refusing to protect them anymore. Afterward, strangers made their non-stranger moves—handshakes, hugs, a crumpled twenty pressed into my palm with a muttered “get yourself something good.” Pastor Jim said, “You spoke truth. That’s never wrong.” Jenkins from Toledo yelled at me for not calling him more often and then drove us for greasy pancakes at two in the morning because grief likes company and coffee and syrup.

My family wasn’t done. They wrote letters that sounded like press releases. They cornered mutual friends in grocery aisles to explain their version. They advised me to think of how this looks. I thought of how it felt and chose that instead.

The best revenge—if we want to use that word—wasn’t the news or the fundraiser. It was the life I built while they talked to each other about optics.

The fund for women veterans needed a name. I said James’s name in my kitchen and it felt right on my tongue. I said Elena’s name and the air changed. We called it the James & Elena Fund because memory isn’t useful unless you attach it to something that gets water to the fire. We didn’t hire PR. We put a coffee can next to the register at the bakery. We fixed a transmission for a woman who blasted music because the silence scared her. We paid for a motel for someone who told me with flat eyes that her parents had changed the locks to make her “independent”. We drove another to her GED prep because entry requirements for jobs don’t ask how you learned to get up early.

At the one-year fundraiser, we cut a cake with one of my knives and one of Diane’s because compromise is the heart of hospitality. The sign over the dessert table said presence > pity. We meant it. I looked out at the crowd and saw people who had met in the weirdest way—over my story—and stayed on purpose. It was a new kind of family. It didn’t require me to audition. It didn’t ask me to shrink. It asked me to show up and feed people, which turned out to be the job I’d always wanted.

My brother texted the night before the fundraiser. We hadn’t spoken in months beyond his attempts to put a prettier frame on their choices. Can we talk? he wrote.

I stared at the three dots bobbing. About what? I typed back.

About ending this, he wrote.

This ended when you told me to get an Uber, I replied. What you’re asking me to end is the part where other people know it happened. The dots appeared, disappeared. He didn’t respond.

My parents didn’t come. I didn’t scan the room for them. Absence speaks. People heard it just fine.

Spring came late and dripping. The garden started slow and then took off like everything else finally remembering how to live under this roof. I learned the weight of a tomato is best judged in the palm of your hand, not by sight. I learned how to tuck vines and pinch blossoms and accept that some branches won’t carry what they started. My friend Val joked that growing things is cheaper than therapy and I agreed until I tallied the soil receipts.

The first time I went back to my parents’ house after all of it, it wasn’t to reconcile. It was to drop off a box of their mail that had been incorrectly forwarded. The porch looked smaller. The maple, bigger. My mom answered the door with the expression you put on for pastors and city officials, not daughters. “We didn’t know you were coming,” she said.

“I didn’t know you weren’t,” I said back.

We stood there with a box of mail between us, proof that the world keeps sending you things whether you open them or not. We talked about weather and the neighbor’s dog and the homecoming of a boy who wasn’t my brother. She didn’t say sorry. I didn’t ask. On the way back to my car, my dad came around the side of the house with a rake. He looked older in the way grief makes you older. He opened his mouth. “How are you?” he asked.

“Good,” I said. It wasn’t fine. It was true.

You can love people and also decide not to set yourself on fire to warm them. That’s not betrayal. That’s a boundary. I learned the difference in a hospital room with a nurse’s hand on my chart and my own hand on the truth.

A few weeks later, Troy appeared at my door with a beer in one hand and an apology in his mouth that he hadn’t quite practiced. “I didn’t—” he began.

“You did,” I said gently. “You didn’t mean to. You did anyway.”

He nodded, looked at the cracked concrete of my walkway, took a sip to buy time. “I hate how people talk about us,” he said.

“I hate how we behaved more,” I said. “That’s fixable. It starts with showing up. Not just for me. For anyone. You get a lot of extra chances in this life, Troy. Use the next one better.”

He stood there awhile like he’d been given a task and didn’t like the instructions. He left without making promises. He texts sometimes now. Sometimes I answer. Sometimes the answer is not a green bubble but a woman’s new understanding that her time is not an infinite resource for fixing other people’s reputations.

The day the tomatoes crowned the cages like it was their idea to do so, I sliced one and ate it over the sink. The juice ran down my wrist and I licked it clean with the hunger of someone who knew a different kind of hunger too well. I whispered James’s name—because saying his name didn’t make my life a tragedy; it made him present. The screen door creaked. Diane walked in and handed me a Tupperware I would never, ever get back to her. “We raised five hundred dollars for your fund at the bake sale,” she announced. “Old men love lemon bars.”

“Who doesn’t?” I said. We laughed and didn’t need to fill the silence that followed.

Later, at dusk, the support group thread pinged with check-ins that were 90% jokes and 10% I can’t breathe. The I can’t breathe parts came without apology. We sent stupid gifs back. We sent the addresses of coffee shops. We sent the truth. I turned my phone over on the arm of the chair and watched night stitch itself across the yard.

My father still lives ten minutes away. Sometimes I see him at the hardware store buying screws as if tightening something could fix a house built wrong. Sometimes he sees me and lifts a hand. I lift mine back. It’s not a reconciliation montage. It’s a nod. That’s where we are. The maple will drop helicopters again in the fall. I am not responsible for sweeping their yard.

This is the part where I tell you the moral, if there has to be one: Family can be chosen. Support can arrive from people who didn’t watch you grow up but still know how to set an extra place at the table. Your worth does not rise and fall on the tides of those who learned to see only the brightest star at their dinner table. Sometimes the only revenge worth pursuing is making a good life a witness.

If you’re reading this because you searched for stories about being invisible and ended up here by accident or hope, here’s mine: I came back from Afghanistan with one arm and the kind of exhaustion that doesn’t answer group texts. My family-treated me like a ghost until other people couldn’t let them get away with it. The town showed up. The nurses showed up. The neighbors showed up. So did I. That last part matters most.

Drop your story in the comments or whisper it into a trusted ear or write it in a notebook only you will ever open. Share the names of the people who carried you when blood didn’t. Say thank you with casseroles and rides and money when you have it and time when you don’t. When you can, plant tomatoes. Clip the first ripe one and eat it over a sink. If you are a person who has made other people small to fit your life, stop. Find a bigger life.

Sometimes revenge isn’t fire. It’s an arrivals gate whether or not anyone stands at it. It’s a hotel key pressed into your palm by a stranger. It’s a room full of women under fluorescent lights passing donuts and telling the truth. It’s a nurse saying you decide. It’s a boundary that bleeds less every time you reinforce it. It’s living better, louder, freer than they expected you to.

And that, my friends, is enough.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load