I Betrayal My Husband In Our Own Bedroom — Now His Silence Is Destorying Me

Part One

I never thought I would be the kind of woman who betrayed the man who loved me more than life itself. For twenty years, my husband, David, had been my anchor, my best friend, the father of our children, the person who made me coffee exactly the way I liked it and knew when to pull me close without being asked.

People say that if a marriage ends, it’s because love died first. I know now that’s not always true. Sometimes love is alive and warm and steady—and still, weakness creeps in. Temptation whispers. You tell yourself your loneliness is special. You convince yourself no one will ever know. You risk everything you can’t replace because, for a moment, you’ve forgotten the difference between a spark and a wildfire.

That night—I don’t dress it up with euphemisms anymore—was short, stupid, and meaningless. “It didn’t mean anything,” is what I said to myself for days afterward, clinging to the phrase like it could make it true. But it meant enough to scorch the one room of our house I had once called sacred. It meant enough that when David walked in—earlier than usual, a file folder still in his hand—his face emptied of every expression I had ever known. He didn’t shout. He didn’t throw things. He didn’t even speak. He just stood there like someone had quietly amputated part of him, turned, and closed the door behind him.

And then came the silence.

I used to say there are a thousand ways to say “I love you” without the words. I learned there are just as many ways to say “I’m leaving you” without keys or suitcases or slammed doors. His silence was not the silent treatment. It was not punishment engineered to soften me up. It was a vacuum, a place where sound disappeared. He continued to come home. He ate at the same table. He answered the kids’ questions with patience and the dog’s wagging tail with a gentle pat. He even once fixed the leaky faucet in the powder room. But the man I knew was gone. He moved around me like a careful archaeologist—notes taken, boundaries marked, feelings kept in tidy bags with labels I could not read.

At first I tried to pull him back with words—riverloads of words. I found myself narrating dinners from the kids’ school awards to the story about the barista who always writes my name as “Olive.” I wrote letters at night when my thoughts were braver on paper than aloud—three-page confessions that burned my fingers, small notes tucked in his briefcase, a folded apology left on his pillow. I made the casserole his mother used to make when he was sick. I stood in the grocery store aisle with tears running down my neck because the apples looked like the ones we picked the autumn before we were married. I begged him to go to counseling.

“Not now,” he said, not harshly. Not anythingly. And then he moved aside to let me pass as if I were someone else on a crowded sidewalk.

Nights were worst. We lay side by side the way strangers do chosen by a booking algorithm—body heat without belonging. Sometimes, when he was half-asleep, I reached for him, fingers trembling at the border. He didn’t push me away. He didn’t lean toward me either. He stayed still, and his stillness hurt more than any shove.

I told myself the affair meant nothing to my heart. That it was a symptom of something wrong with me, not with us. That I had wanted to feel exciting instead of reliable, wanted to be seen instead of just depended on. None of that sounds noble. It isn’t. It was selfishness in a dress that looked like sadness. And because it happened in our room, that one decision echoes from the closet to the headboard to the nightstand where his wedding ring leaves a faint circle when he showers. He doesn’t have to speak the word “betrayal.” Every quiet breath beside me says it for him.

We have two children, which complicates everything and clarifies nothing. Emma is fifteen and has David’s eyebrows and my habit of picking nail polish off in perfect comma-shaped strips. Sam is ten and believes toasted marshmallows are a food group. They do not know the details. They have felt the weather change. “Is Dad mad at you?” Emma asked one night, sitting on my bed, back against the headboard where his pillow used to be. “He… seems… different.”

“He’s sad,” I said, and I watched her file that word in a place that mattered. “We’re… figuring things out.”

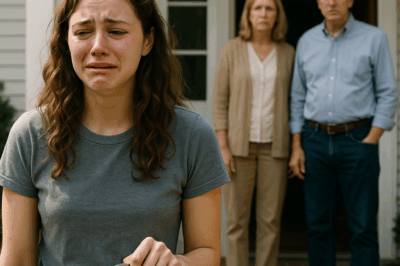

“How can I help?” she asked, because she is the kind of person who asks that. I should have told her there was nothing she needed to carry. Instead I cried, and she held my hand, and later I went into the bathroom and sat on the floor and hated myself for letting any of my tears be hers to see.

On the third night after he found me, I opened a new note on my phone and wrote the word “timeline” at the top. Then I wrote every contact, every lapse, every lie. Not because he asked. Because I had read somewhere—on websites for people like me, people who had blown up their lives with a match and then had the gall to ask for a fire extinguisher—that this was a way to stop trickle-truth, to make the bleeding honest. The next morning, I printed thirty pages and slid them into a manila folder and left it on his nightstand.

He didn’t open it. Not then. Not that day. I found it two mornings later on my desk, untouched, like a package that had been misdelivered.

I thought about defensive little half-truths, about how he works late too sometimes, about how I have felt more parent than wife in the years of double shifts and teenage storms. Then I imagined his face if I said any of that. It was the easiest moment I’d had: I said none of it.

On the sixth day, I made a counseling appointment for myself. It felt both like cowardice and like oxygen. The therapist, a woman named Rita with soft sweaters and hard eyes, didn’t let me talk about him for the first session. “Tell me about you,” she said, without pity. I told her I am a nurse because my hands want to fix things and my ears want to hear what hurts and my feet like always having something to do. I told her my parents loved me in a way that looked like checklists. I told her about the night I met David at a fundraiser for the pediatric ward and how he told a joke about hospital coffee and I laughed too hard, and he said, “I don’t drink coffee either, but I’ll bring you water exactly the way you like it,” and he has done it every day since—his water, cold, lemon slice upright like a coin on the lip of the glass, my water, room temperature. I told her the thing I have not admitted even to myself: that I wanted to be the kind of woman who could say no because her yeses meant something, and I failed.

She nodded, and I cried into a wad of tissues, and she said, “We will make a plan for your own recovery. What he chooses is his to choose.”

“His silence is killing me,” I said at the end, when my mouth felt tired and my eyes felt like sand.

“Maybe the silence isn’t about you,” she said gently. “Maybe it’s all he can do to stay.”

In the second session, she told me about boundary-making like it was a map. No contact with the other man, she said. Ever. Text him, “Do not contact me again,” then block, then delete. Find a support group. Offer transparency to your husband, not as a performance, but as respect: phone, passwords, locations, calendars. Keep a “sobriety” log for your behaviors—the people-pleasing, the spinning stories, the impulse to manage his feelings by performing guilt instead of doing work. Make a restitution list of what you took from him and what you can give back: details, safety, time, steady effort.

“Can I fix this?” I asked at the end, because I am nothing if not a woman who wants to check the right box.

“You can fix you,” she said. “You can make the conditions under which a marriage could heal. He can decide if he wants to live in those conditions. That is the terror and the grace.”

On day thirteen, David came home later than usual, the dog trailing him closely, confused by our altered patterns. The kids were at my sister’s, something I had asked for in advance, something he’d agreed to with a curt text that ended in a period. I set out water with lemon, then remembered and poured it into my own glass.

He came into the kitchen and leaned against the counter. He looked older—like someone had changed the lighting in the house.

“I read it,” he said finally, tapping the folder I hadn’t noticed he was holding.

My stomach dropped to the level of my ankles. “Do you… have… questions?” I asked, and the words felt like a ritual in a language I had learned last week.

“I don’t even know how to have questions,” he said, and his voice broke on the last word. “How long? Why here? Why him? They’re all questions that won’t give me anything. You told me to imagine your face if you tried to explain. Imagine mine if I ask.” He looked at the window, and I watched his profile the way you look at someone asleep.

“I will answer anything you ask,” I said. “Now or later. I’ll answer it all.”

He nodded. “Not now.”

We stood in that kitchen with the humming of the refrigerator sounding like a small engine keeping us alive.

Finally, he said, “I want you to schedule counseling for us. I can’t sit in silence forever. But I can’t sit in this house and talk about it either.”

“Okay,” I said, and it was the first word of the day that didn’t feel like a lie.

“And,” he said, and this time his voice was not gentle, “you need to move into the guest room.”

I nodded, as if he’d asked for water. “Okay.”

It wasn’t enough. It was too much. It was a door stopping a flood.

That night I packed a bag for the guest room with exactly the kind of care I’ve always mocked in magazine articles. I put my toothbrush in a travel case so it didn’t touch his by accident. I folded shirts without shaking them so he wouldn’t hear. I took the ring off and slid it back on the chain. The bed felt like a waiting room. I stared at the ceiling and didn’t sleep.

The kids noticed the change the next morning, because children live inside weather. “Why are you sleeping in the other room?” Sam asked, still holding his cereal spoon like a paintbrush.

I didn’t look at David, because we had agreed the night before in the smallest of joint decisions that we would tell the truth without telling the story. “Because grown-ups get hurt and need space sometimes,” I said.

“Did Dad hurt your feelings?” Sam asked, almost indignant.

“No,” I said. “I hurt Dad’s.”

Emma didn’t say anything then, but she looked at me with a knowledge that made me want to send her back to the version of childhood where I taught her to whistle through a blade of grass and she thought I was a magician.

We started counseling with a woman named Lila who had a braided bracelet and a calendar with squares big enough for grief. She didn’t ask us to sit closer. She asked us to speak in turns. She made me look at David when I said, “I did this to us.” She made him look at me when he said, “You took something I did not know could be taken.” She made us both write down what safety would mean and then swap papers like kids in a classroom being asked to grade each other’s sincerity.

David’s list was exacting. No contact. No secrets. Find another job if that’s what it takes to feel safe. Tell me when you’re lonely before you’re dishonest. Monthly check-ins where you answer the question “Have you been honest?” without looking at your lap.

My list was different. Talk, but don’t talk at me. If you’re going to leave, tell me before you pack. Don’t punish me with extra kindness—that makes me feel like an expiration date. Let me make amends with something besides groveling. Tell me if you’re having an affair with your rage so I don’t think I’m the only unfaithful person in the room.

We left those sessions exhausted the way runners leave a race they weren’t trained for. We ate tacos in the car and didn’t talk and then, sometimes, we would drive past our house and go park by the river because the inside of a marriage felt bigger if there was water nearby.

At work, I told my supervisor the truth in the smallest container. “My husband and I are in crisis,” I said. “I need to change shifts sometimes.” She hugged me the way a nurse hugs another nurse—with her head turned so our stethoscopes didn’t poke each other.

Every morning I pulled a stool into the bathroom and wrote a sentence to myself on a sticky note because Rita told me I had to become a reliable narrator of my own life. Today I will not manage his feelings. Today I will not ask him for a verdict. Today I will call the support group. Today I will text the other man: “Do not contact me again,” block, delete. Today I will tell the kids I love them and that we’re trying.

I expected David’s silence to shift as I shifted. It didn’t. Not at first. It thickened, actually, into something heavier and more honest. If he wasn’t ready to talk, he didn’t. If he couldn’t sit in the same room, he went outside without apology. Sometimes he cried in the shower and tried to hide it by turning the water hotter, and sometimes he didn’t bother to hide it. Once he screamed into a towel. I let him. It was the first time his silence had sounded like a sound.

On a Saturday afternoon in late spring, the kids went to my sister’s. I was in the backyard under the maple tree with my feet in the grass, the dog panting, the sun a little too bright. David came out in bare feet, sat down with his back against the trunk, and said, “You are not the worst thing you’ve done.”

I looked at him, and my mouth couldn’t find the right shape for the gratitude. “Neither are you,” I said, because while I had been apologizing, I had also discovered a truth like a splinter under skin: his ownership of pain had become a way not to own anything else. Grief is not license. We were both going to have to learn new rules.

“Lila says we should do a therapeutic separation,” he said then, like he was reading a prescription he didn’t want to follow. “Three months. Two homes. See each other with intention, not by proximity.”

I had expected everything but that. Divorces or vows or a sudden miracle. I had not expected practice. “Okay,” I said again, because the word had become my side of the bargain.

We told the kids together, on the couch we used to whisper on. “We’re going to have two houses for a little while,” I said. “Dad’s going to stay with Uncle Matt. I’ll keep the house with you and Biscuit. We will both be here, just not at the same time.”

“Is this because of Mom?” Emma asked with a steadiness I had not earned.

“Yes,” I said, and I watched David’s jaw soften because truth is a form of respect.

“I hate it,” Sam said, and we agreed.

The day David moved a few boxes to his brother’s, he hugged Biscuit for a reckless amount of time and then stood in the foyer like a man who wanted to take back the last six months minute by minute and could not. “I don’t know how to do this,” he said.

“Neither do I,” I said. “We’ll do it badly and then better.”

He laughed once. “That has been the motto of our entire marriage, hasn’t it?”

“God, I hope not,” I said, and for the first time, we both laughed in a way that did not feel like cruelty to the person who wasn’t laughing.

In the separation, time changed shape. I missed him in ways that hurt and didn’t. I slept diagonally because I could. I kept the TV on some nights so the room didn’t speak too loudly. I took the kids to the farmer’s market where we bought strawberries that tasted like strawberries and bread that made us whisper in a church voice even though we were outside. On Sundays when it was his turn, he took them fishing and sent me pictures of Sam holding a fish like a trophy and Emma pretending to be bored and failing. We texted about logistics and sometimes about nothing—memes about nurse life and dad jokes and a photo of the dog sleeping like a human on my pillow and another of the dog sleeping like a dog on his.

Once, I was dropping the kids at his brother’s and he came out with a box labeled “Mail.” He handed it to me and I saw it wasn’t mail. It was my college sweatshirt, the one from the year we met, the one he wore when he missed me and smelled like laundry soap and books. He put it in my hands like offering a peace treaty we hadn’t written yet. I took it. We didn’t talk about it.

Lila called it “building a new marriage while mourning the old one.” Rita called it “sobriety.” My mother called it “unseemly.” Hana called it “work,” and then fed me soup.

On the last day of our agreed-upon separation, we met at the park without kids or dog or family. We sat on separate benches because it felt like we should. The air tasted like rain and decisions.

“I don’t know what to do,” David said, honest to the bone.

“Me neither,” I said. “Do you want to do it together?”

He stared at the puddle near his foot as if answers could drown and be scooped out. “I want to stop feeling like silence is the only safe thing,” he said. “I want you to stop performing guilt and start building something. I want to want you without hating myself for it.”

“I want to give you a new memory of our bedroom,” I said. “One that does not erase what happened but refuses to let it be the last word.”

He looked at me then in a way that had nothing to do with forgiveness and everything to do with human recognition. “Do you still love me?” he asked.

“I have never stopped,” I said. “Even when I did something that made that sound like a lie.”

He nodded as if he had expected that to be the answer and not expected to believe it. “Okay,” he said, and the word had the weight of a contract.

We didn’t move back in that night. We didn’t make love. We went to the hardware store and bought paint—honey white with a whisper of blue, like a morning sky that had decided to be kind. We patched nail holes and laughed when the dog got paint on his ear and we moved the bed two feet to the left because it felt like something had to be different even if our eyes were closed. We threw out the old duvet cover. We bought new sheets that felt like an apology I could actually sleep in.

That first night back, we lay side by side, our elbows an inch apart—a cautious treaty. “I’m sorry,” I said into the dark because some phrases are meant to be repeated until they change shape. “I am too,” he said, and he meant for what he had to do to survive me.

His silence didn’t disappear. It changed texture. There were still days when we had nothing to say that would not re-open something. On those days, we wrote notes: “Sad but here.” “Angry but grateful.” “Tired but staying.” We learned to make dinner without performing normalcy—tacos, silence, “pass the guac,” silence, “do you want water?” The absence in the pauses turned into space, not punishment.

Six months later, on a Sunday morning, he climbed into bed with a mug of room-temperature water and a slice of lemon, upright like a coin on the lip of the glass. He handed it to me like a ceremony. “I never stopped,” he said. “I just couldn’t make it mean anything.”

“It means everything,” I said, and he smiled with his eyes but not his mouth because that is how smiles begin after grief.

On the anniversary of the day everything broke, we drove to the coast with the kids and the dog because I wanted to stand in front of water again and remember that things can be put back into motion. David and I sat on a driftwood log while the kids dared waves to touch their knees. He pulled a small box from his pocket. I felt my stomach lurch at the shape of it—reflexes learned as a child, as a bride, as a sinner.

“It’s not what you think,” he said quickly with a half-laugh. “It’s worse. It’s symbolic.” He opened it and on the felt lay two simple bands—mine and his—the same ones we had exchanged twenty years ago, now cleaned, unadorned.

“I took mine off the night I left,” he said. “I tried to put it back on the night I came back. I couldn’t make my fingers do it. I need a new way.”

“What’s the new way?” I asked, shaking.

“Not on the anniversary of our wedding,” he said. “Not on the day you hurt me. On the day we chose to keep going.”

I held out my hand. He slid the ring on, and for the first time since that night, I did not feel like I was stealing something that didn’t belong to me. I took his, and it slid home with a small click that sounded exactly like a door closing gently in a house where people have learned not to slam.

“Does this mean it’s all okay?” Sam yelled from the waterline, and Emma rolled her eyes the way fifteen-year-olds are required by law to do.

“No,” David said, and he looked at me with the kindest kind of honesty. “It means we’re doing it anyway.”

“Good,” Emma called. “Because we like you two together more than we like you apart, and that’s saying something.”

The dog barked at a wave. The ocean kept doing what it does—coming and going, never once asking permission to keep trying.

The silence didn’t destroy me. It dismantled me. There is a difference. The parts of me that were not built to hold a marriage fell away. The parts that were worth keeping learned how to speak.

When I betrayed my husband in our own bedroom, I thought the worst punishment would be rage. I was wrong. Silence forced me to hear myself. It became the hard ground I learned to kneel on. It taught me that apologies are not payments; they are seeds—and seeds need quiet to grow.

We planted a maple sapling in the corner of our yard this spring, close to the place where I sat with my feet in the grass and said, “Okay,” for the first time. The kids wrote their names on rocks and tucked them around the base. David pushed soil with his hands the way he did when we were young and broke and moving into our first apartment and the landlord said “no nails in the walls” and we hung our photos with washi tape and stubbornness.

“Do you think it will make it?” he asked, patting the dirt like a prayer.

“I think it already has,” I said.

We named it Grace because we are unimaginative in the ways that matter and creative in the ways that don’t. Every fall it will let go and still be itself in winter. Every spring it will make new things out of old wood. Our dog will pee on it, and we will tell him not to, and he will, and it will survive anyway.

If you are reading this to find out whether he forgave me, I can’t give you a clean verdict. Forgiveness has not been a single ceremony. It has been a series of choices: two people sitting at a table doing the worst kind of homework and then deciding to stay for dessert. The marriage we had is over. The one we have now is less romantic and more honest. Sometimes we miss the old one. Then we remember we have a tree to water.

On the night we finally made love again in our bedroom—the room I am still learning to call sacred—we cried and laughed and apologized and did not apologize and then fell asleep with our feet tangled and our faces turned toward the same window. The next morning, he brought me water the way he always has. The lemon slice sat upright like a coin on the lip of the glass.

“Room temperature,” he said, his voice a whisper that was not silence. “Right?”

“Right,” I said, and we drank.

Part Two

Spring wore itself into summer the slow way—through the maple’s new leaves and the dog’s fur drifting like snow on the rug and the kids’ backpacks dropping in a daily avalanche by the door. The hardest things didn’t get easier; we just learned how to do them without pretending they were not hard.

On the first night of June, we had our third joint session with Lila after David moved back in. She drew a rectangle on a pad and wrote HOME at the top. Then she drew two smaller rectangles inside and labeled them PAIN and WORK.

“This is not about choosing one or the other,” she said. “It’s about making space for both. Pain without work becomes punishment. Work without pain becomes performance. You cannot build a life on either alone.”

I stared at the rectangles, the way a nurse sometimes stares at a monitor: hoping to read the rhythm and find a reason not to panic.

David said, “Sometimes, when Olivia says ‘I’m sorry’—even now—I feel like I have to translate it into something I can use. Like, was it ‘I’m sorry because I got caught’ or ‘I’m sorry because you hurt’ or ‘I’m sorry because I want this to go away’? I need sentences I can trust.”

“Then ask for them,” Lila said. “Don’t punish yourself for needing what you need. Say, ‘I need you to say what you’re sorry for today.’”

He turned to me. “I need you to say what you’re sorry for today.”

The old part of me wanted to roll my eyes and groan that we’d done this already—that he’d read the thirty pages, heard the confessions, seen me cry into a washcloth so our kids wouldn’t think their mother melts. But the new part took a breath and made a list.

“I’m sorry I brought an outsider into our home. I’m sorry I told lies crafted to be easy to believe. I’m sorry I let loneliness make me dangerous. I’m sorry the sound of our bedroom door closing became a trigger. I’m sorry I made you the kind of man who had to learn to count my words like tablets in a bottle. I’m sorry I made our children learn a language I should have spoken before.”

“Okay,” he said, and I could see the rectangle called WORK get a little bigger.

We also learned how to apologize to the kids without making them archivists of our grief. On the first July thunderstorm, when Emma came into our room with slippers shaped like cats and asked if she could sleep on the floor the way she did when she was little, we lifted the duvet and let her climb in between us. In the dark, she whispered, “I don’t always know where to put my anger. Sometimes I aim it at you, Mom. Sometimes at you, Dad. Sometimes at my algebra teacher.”

David said, “Aiming it at algebra is a classic choice.” He let the joke break the tension and then added, “You’re allowed to be mad at us. Both of us. For different things.”

“Are you mad at Mom?” she asked, and there it was: the clean blade of a teenager’s curiosity.

“Yes,” he said, and then, after a breath, “I’m also proud of how she’s working. Those two things exist in the same house.”

In August, on a Tuesday that smelled like ripe tomatoes and sunscreen, the other man left a letter folded into thirds under the wiper blade of my car. He had found my new number through someone at work and then my new car through noticing where I parked—I learned all this secondhand because I never opened the letter. I took a picture of the envelope, sent it to David, then to Lila and Rita, then to myself because the girl I used to be would have read it “just to get closure.” I held it like you hold a hot kettle—respectfully—and dropped it into the shred bin at work, then marched upstairs and told HR on legs that wanted to be anywhere else.

My job changed shape because of that. The administrator shifted my schedule so I didn’t have to run into him. My supervisor ran interference with a fierceness I didn’t know she had. David sent a one-line email from his personal account to mine, CC’ing our therapist: Thank you for telling me within ten minutes, not ten days.

I printed that email and put it in the folder with the thirty pages. Not because I wanted to keep a record of praise. Because I needed to know that this new muscle I was building—transparency—was strong enough to lift something besides guilt.

September was about school forms, and later bedtimes, and the way grief sometimes hides in the lost-and-found box. One night, after Sam’s soccer game—orange slices, a hot dog, his hair plastered to his forehead with sweat—David and I sat on the house’s back steps, our knees touching on purpose. The maple overhead had learned how to speak fall in a dozen shades.

“I have to say something,” he began, and that tone—patient, heavy, unwavering—made me set my plastic cup of water down on the step like it could eavesdrop.

“I cannot live waiting for you to relapse,” he said. “That isn’t love. It’s surveillance.”

“I can’t live performing remorse,” I said. “That isn’t love. It’s theatre.”

We both nodded, because you don’t always know what you need until the person who needs it says it out loud.

“Let’s build rituals,” he said, surprising me. “Not rules. Rules make me feel like a probation officer in my own house. Rituals make me feel like… like we have a life.”

So we made some. Rituals are not contracts; they are constellations. We started lighting a candle on the kitchen island after dinner and asking one question each—work, kids, faith, fear, something we used to hide behind “fine.” We put our phones in a basket by the door at 9 p.m. We went to a support group for couples like us—me, an unfaithful spouse, him, a betrayed one—and learned how to sit in a room with eight people who could say the words we were still afraid of. We sat on the same side of tables in public, not because we were united against some external force, but because we wanted to shoulder the world together again.

On the last Thursday in October, David took me to the restaurant where he had asked me to move in with him two decades earlier. The place had gone through three remodels and still smelled like garlic. He didn’t bring a box this time, thank God. He brought a napkin with writing on it. It was not poetry. It was not a vow. It was an inventory list.

Things I Missed While I Was Silent:

Your laugh when something truly awful on TV happens and you feel permission to be cruel to a fictional person for five seconds.

The way you tuck your left foot under your thigh when you read.

You telling me when you’re scared before you do something dangerous to feel alive.

Half-finished mugs of chamomile on every flat surface we own.

Your hands on my back in church when the hymn doesn’t fit in my throat.

You whispering, “He’s not dead, he’s just asleep,” at that crazy ballet because the man wouldn’t get off the stage.

He folded it and pushed it across the table. “I say these out loud because I spent so long speaking only to my fear.”

I wrote my own inventory. Not of what I missed. Of what I learned.

Things I Learned While You Were Silent:

I do not need to be punished to be changed.

Attention is not love.

Secrets rot the houses that keep them.

My body is not a bargaining chip for guilt or relief.

I am capable of telling the truth even when it makes me unlovable for a minute.

He reached for my hand, palm up. We sat in that restaurant as two people nobody would choose as models for perfect marriage and were grateful to be models for something truer: stubborn mercy.

Then November picked up a handful of stones and threw them at us.

Emma came home with a busted lip and a story about a boy who thought “no” was a puzzle. She told her dad first, because girls tend to tell their fathers when their mother’s tenderness feels like a mirror they don’t want to look into. I listened from the hallway, my chest a drumline.

“She said no,” David said later, his hands shaking. “She said no and he pushed. I don’t want to teach her to be afraid,” he added, a quiet fury in his throat, “and I want to put the world in a jar and screw the lid on tight.”

We went to the school. We spoke to a counselor who was capable of saying “assault” without flinching. We taught our daughter the difference between forgiveness and access. We slept with the hallway lamp on for a month because light is sometimes more than photons. I watched David talk to our daughter about consent and power and fear and I thought: my husband is building the kind of safety I failed to learn how to build.

On a Tuesday in December, I got a call at work from a number labelled PRIVATE. For a second my stomach did that acid wave thing, but I answered. A voice—female, younger—said, “This is Mia. I think I’m the new you.”

My hands did not know where to be. I stepped into a supply closet and shut the door with a click. “I’m sorry,” I said, not because I had anything to do with her choice but because the club is large and the membership dues are terrible.

She said, “He told me he left his wife six months ago. He said you were controlling. He said you were cold.” She sucked in her breath—it caught like thread on a rough nail. “I saw the wedding ring tan line when he reached for his coffee. I’m not proud that I didn’t ask then.”

I told her everything I wished someone had told me. “Block him. Tell a friend. Go to therapy. You don’t have to confess to his wife; she has enough pain.” Then, after a beat, “You are not so special that you should be punished forever, and you are not so foolish that you cannot learn.”

When I hung up, I went to the bathroom and washed my hands like I could scrub off the sensation of touching a newer version of my worst decision. When I came home, I told David about the call. He put his palms on the counter, grounding himself. “Thank you,” he said. “For telling me the same day. For not making me read it in a folder.”

Christmas came with all its rituals and knives. We went to my parents’ house and sat through carols and casseroles and the annual argument about whether tinsel is festive or tacky. My mother, who will die on the hill of “festive,” cried at midnight mass when the choir sang “O Holy Night.” I didn’t pretend I knew why. I just handed her a tissue with the grace that comes from being human in December.

On New Year’s Day, we took the kids to the maple, now stripped of its leaves, and we wrote resolutions on scraps of paper because I am a nurse, and I like lists. Emma wrote, “Be less afraid of saying no,” and tied hers to a branch with baker’s twine. Sam wrote, “Learn a kick flip,” because he is ten and more wise than anyone I know. David wrote, “No more pretending,” and I wrote, “Tell the truth first.”

We burned the scraps in a terra-cotta pot because children love containment. The smoke rose up and did not make shapes. Sometimes your rituals don’t change the sky. They just change you.

In late January, David’s father had a small heart attack at the hardware store he’s run since before David could drive. I wanted to rush into the emergency room with a cart of guilt and empathy and take over, because that is my default setting. Instead, I called David from the parking lot and asked, “Where do you need me?” He said, “I need you to cover the kids so I can sit with him and not be a ringside announcer for my father’s mortality.” I went home. I made hot chocolate. I taught Sam to play gin rummy and pretended not to care that he is a card shark.

There are a hundred ways for a marriage to fracture quietly. I have learned there are a hundred ways to stitch it quietly back. Not dramatic gestures. Not Facebook posts. Not vow renewals in fields with fairy lights—though I will never disparage fairy lights. I mean the small mending: a text that says, “I’m late. Not cheating. Just traffic.” A hand on a back in the middle of the night when one of you wakes from a dream where the other leaves. A calendar entry titled HARD TALK because you have learned to make appointments with pain so it doesn’t show up and eat dinner with your kids.

On our twenty-first anniversary, we did not go to the coast. We went to a diner off Route 17 that makes pancakes the size of hubcaps and coffee that tastes like regret. We ordered too much. We sat in a booth where the vinyl has split like a mouth. David slid a Polaroid across the table to me. It was of our maple tree last fall—yellow like a yes. He had written on the white bottom border: We made this.

“We did,” I said. “And we almost unmade it.”

“And then we made it again,” he added, because he likes to win, and I like to let him when he is right.

When I tell this story to the version of you that is still at the kitchen table holding a glass of water you cannot swallow, I want to do two things at once: refuse to glamorize the affair as a symptom worth understanding more than its damage, and refuse to glamorize my husband’s silence as some saintly strategy. He is not a saint. I am not a monster. We were two people learning to breathe underwater. The silence was his oxygen mask. It saved him, and it almost suffocated us. We had to learn to take turns.

Now, some endings:

The other man left our hospital for a job across town that pays less. I have not seen him in nine months. Sometimes I feel the tug of wanting to check his LinkedIn. I do not. I text Rita instead: Haven’t peed in the poison today. She responds with three clapping hands and one maple leaf.

Emma went to the winter formal in a black dress and red sneakers because she is my daughter. Her date kept his hands where they belonged, and when he didn’t, she moved them and then moved his entire person away. She told us about it the next morning over pancakes. We cheered like fools.

Sam landed his kick flip in April and broke his wrist in May and told everyone who would listen that it was “worth it.” I took him to the ER on a night I was not scheduled to be there, and the nurse on duty patted my shoulder and said, “Sit down. Be a mom.”

My mother sent a text on Mother’s Day that said, You have a good husband. It was the closest she has come to apology; I accepted it at face value because I am tired of not accepting what is simple.

The maple needed staking during a windstorm in March. David and I went out into the rain in pajamas and put our hands in the mud together. Sometimes that is the whole metaphor.

The first spring after the worst winter, the dog dug up one of the rocks the kids had placed around the maple. It was Emma’s, with a Sharpie heart that had bled in the dew. She came outside, hair still wild from sleep, and reburied it with more forever than most people put into mortgages.

“Do you think trees forgive us?” she asked, and I thought of the night I betrayed her father and the morning I told her we would try to be better people than the ones who did that.

“I think trees keep growing,” I said. “Even when we don’t deserve it.”

We stood there, three minutes or thirty, it’s hard to tell when your heart stops counting time. The wind moved through the branches and made a sound like a hush, not like a silencing but like the way a room sounds when a story is about to begin.

Our story is not pretty in the museum sense. It has fingerprints all over the glass. It has scuff marks. It has captions that say, “Here is where we almost lost this.” It is ours. It is enough.

When David brings me water now, he puts the lemon slice upright like a coin on the lip of the glass and waits for me to smile before he lets go. It is silly. It is sacred. It is both. He hands it to me and says, “Room temperature, right?” I take it and say, “Right,” and then we drink like people who have learned the price of thirst.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

“He Already Had Everything, So Why?” — A Veteran Cop Turns In His Son, Now Facing AGGRAVATED MURDER And The DEATH PENALTY

Authorities identified 22-year-old Tyler Robinson after a family tip and arrested him late Thursday at the Robinsons’ $600,000 Washington, Utah…

My Mom Laughed: “No Wonder You’re Still Single at 31” — She Had No Idea About My Secret Wedding… CH2

My Mom Laughed: “No Wonder You’re Still Single at 31” — She Had No Idea About My Secret Wedding… …

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. CH2

My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life. …

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. CH2

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. Part One The room was…

She laughed in my face, claiming i was never legally married to her son. CH2

She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son Part One When people talk…

Why do you hate your parents? CH2

Why Do You Hate Your Parents? My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to…

End of content

No more pages to load