Husband Left Me For My Sister, So Our Grandmother Changed Her Will On Christmas Day

Part One

The day the text arrived, snow flurried past my kitchen window like confetti someone forgot to clean up after a parade. I had my red pen uncapped over a stack of math quizzes when my phone buzzed.

Mandy: Hey, can you watch the kids this weekend? Dan and I want to go look at houses by the lake.

I read it twice just to be sure my eyes weren’t turning grief into parody. My sister asking me to babysit while she and my husband—no, my ex-husband, though the legal word hadn’t caught up to my heart yet—spent the weekend touring shoreline properties the way we’d once dreamed of doing together.

It had been eight months since I’d borrowed Dan’s laptop to order a gift for our son and found the hotel confirmation first, then the thread of messages, then the photos I didn’t know my sister had ever let a camera see. Eight months since “we’ve grown apart” became a sacrament he decided to break in front of me at our kitchen table. Eight months since my sister, three years younger and always reaching for what wasn’t hers, moved her suitcase into his condo and posted a caption with a champagne flute emoji that said, sometimes love surprises you.

I put my phone face down and capped the red pen because neither object in my hand was safe.

What I remember most about those first weeks is noise and silence: the neighbors’ pitying hush at the grocery store; the roar of my own blood when I tried to sleep; my son Jack, nine, telling me with solemn clarity, “Dad loves Aunt Mandy now but he’s supposed to love you.” My daughter Sophie’s small hand tapping my cheek at 2 a.m. to ask, “Is Daddy coming home if I’m extra good?”

I learned to answer without lying and without letting my voice splinter. “Dad loves you. And our home has changed. That’s true. But love doesn’t leave, even when people do.”

Some nights I believed myself. Others I sat on the kitchen floor with a dish towel pressed to my face while the dishwasher hummed like a sympathetic creature.

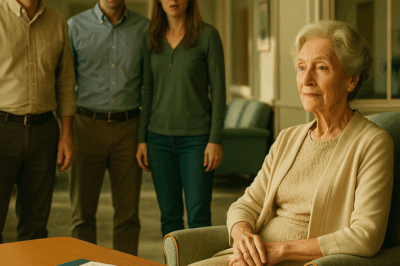

It was my grandmother, Eleanor—Ellie to anyone who had ever been fed at her table—who refused to let me drown quietly. At seventy-eight, she still moved through her Victorian house like a general through a field camp, issuing orders to a roast chicken and a wobbly-legged great-grandson with equal authority.

“Come Sunday,” she said on the phone one evening, a command disguised as an invitation. “You. The children. Wear something warm. Peter will be here.”

Uncle Peter, my father’s brother, was a big-shouldered man with the gentle hands of an antiques dealer and the patience of someone who can tell the difference between a valuable chip and a ruinous crack. I almost told them both no. Talking requires words, and I had been rationing mine. But something in Ellie’s voice, the soft iron of it, made refusal impossible.

Her house smelled like rosemary and past happiness when we arrived. Jack and Sophie beelined for the backyard where a new swing set—the kind you can’t assemble without swearing—gleamed under a dusting of snow. Their laughter hit me like medicine. Ellie poured me wine and put a plate in front of me with the precision of a surgeon and the tenderness of a grandmother who has watched her family break and reform more times than a teacup should have to.

“Now,” she said, sitting across from me with Uncle Peter at her flank. “Tell me everything. No embroidery. No brave face.”

So I did. I told her about the email confirmation from Silver Lake Resort the same weekend Dan said Chicago and Mandy said a girls’ trip. I told her about opening messages with hands that had never trembled over anything but a newborn’s soft neck. I told her about walking my children through a separation, about my sister’s angles on social media, about the text asking me to babysit for the lake-house-shopping weekend. When my voice finally gave out, Ellie’s eyes had gone from blue to steel.

“And the trust?” she asked.

“The what?”

She glanced at Peter. “The trust I set up for each of you girls when you got married. Your grandfather insisted we protect what we built. You and Mandy both received funds—yours to be invested for your household and your children’s future. Daniel convinced me three years ago to let him manage your portion, said he’d put it into better vehicles. He sent reports. I didn’t like him then. I like him less now.”

I stared at her. I am a schoolteacher. If I find twenty dollars in a coat pocket in March, it changes my mood for twelve days. The idea that there had been money meant for me—for my children—tucked into the framework of my life like a beam I didn’t know existed made my index finger go numb.

“How much?” My voice sounded far away, as if it were asking the question from upstairs.

Peter slid a folder across the table. “Enough that you shouldn’t have to choose between paying the gas bill and buying new snow boots,” he said gently.

Ellie nodded to the folder. “Lawrence will meet us tomorrow. He’s been your grandfather’s attorney since nineteen-ninety-two. Don’t borrow trouble tonight. Eat. Sleep. We’ll handle daylight with daylight.”

Lawrence—and daylight—revealed more than a trust mismanaged. The money that should have been worth nearly three hundred thousand was an outline drawn in disappearing ink: transfers to accounts we couldn’t see, “investment opportunities” with no paper, airfare to Bali, a down payment on a car that did not sit in our drive. Prenup clauses I’d signed at twenty-three because love makes paperwork feel insulting turned out to be the umbrella over my head now: the house I’d bought with money from my mother’s side was untouchable; Dan couldn’t claim alimony; I owed him nothing but the civility our children deserved. But the trust. The trust was a theft with our children’s names on it.

“You’ll survive this,” Ellie said one night as we washed dishes, her hands blue with veins but steady as she passed me a casserole dish older than I am. “Green women have survived worse. Your mother survived losing your father at forty. I survived the crash of ’87 with a shop full of people who suddenly couldn’t pay. We keep what matters. We outlast what doesn’t.”

I wanted to believe her. I wanted to be the heroine of a story where betrayal became a preface and the main plot was resilience. Some days I could fake it. On others, I watched the neighbor’s Christmas lights blink and wondered how people learned to go on with their hands still working.

Then December slid toward Christmas, dragging dread behind it. The Green family’s Christmas at the lake house is as traditional as gravy. We gather in a ring large enough to confuse Santa’s GPS and orchestrate a present-opening ritual so slow and attentive you can hear the tape tear. Every year, after stockings and cinnamon rolls and the children’s crescendo, Ellie makes an announcement. Sometimes it’s a business decision, sometimes a property shuffle, sometimes something as simple as “this desk goes to Rebecca when I’m gone.” It’s a way of keeping legacies tethered to faces while the faces can still blush with surprise.

“You’re coming,” she told me when I called to say my stomach turned inside out at the thought of seeing Dan and Mandy together under the golden light. “You. The children. Wear the burgundy dress. Sit next to me. And bring the cranberry walnut bread. It will be important to have the smell of it in the house.”

“You and your announcements,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady. “What is it this year?”

“You can find out with everyone else,” she said. “I do not play favorites out loud.”

Liv—my friend and fellow teacher, the kind of friend who shows up to move a couch and then suggests rearranging your life—had a different kind of plan. “Devastatingly polite,” she said with surgical satisfaction over coffee. “You go. You look phenomenal. You say please and thank you. You comment on the wreaths and the roast. You do not cry. You do not break. You do not give them a story that makes you the problem. You be the mirror. Let them see themselves.”

The thing about devastation as strategy is that it requires an upright spine. Mine did what I asked of it that night. I wore the burgundy dress. I made the bread. I set my face into the expression I use when a parent tells me their child should be allowed to keep a frog in their desk. The lake house door swung open and family poured over us like warm gravy: cousins, aunts, uncles, the heat of people who know how to fill space with cheer. And then there they were: Dan in a sweater I’d never seen, Mandy in an emerald dress with a necklace I’d never chosen. His hand found the small of her back like it had learned a new address. Her smile flickered when she saw me. My stomach did nothing, which might be the bravest thing it’s ever done.

They didn’t speak to me at first. Which was fine. I spoke to everyone else. I delivered my bread to the kitchen, and Ellie kissed my cheek and said the sentence that has become a hinge for my life: “Sometimes justice takes the long way around, but it does arrive.”

When the gifts finally circled to Ellie, she didn’t reach for one. She stood. Her apron was festive without being silly, her hair as precise as a signature. “Before I open anything with ribbon on it,” she said, “I have business to conclude.”

The room obeyed.

“You all know I make one announcement a year. This year’s is about the future. I have lived long enough to know who people are when they are full and when they are hungry.” Her eyes moved from face to face like a lighthouse beam, then fixed on Dan and Mandy. “Betrayal can be forgiven. Cruelty should not be. Daniel, you took what was not yours in the dark and told yourself it was an investment. Amanda, you took what was not yours in the light and told yourself it was love.”

She pulled a folder from beside her chair. “Effective today, the lakefront parcel goes to Rebecca and her children. The business shares intended for Daniel and Amanda are reassigned to Rebecca, with a portion held in trust for Jack and Sophie until they turn twenty-five. A new educational trust for the children replaces the funds Daniel drained. The rest of the changes are outlined in the envelopes you’ll receive before you leave.”

Mandy made a choked sound like someone who has swallowed the wrong truth. Dan went the color of unbaked bread. Someone’s fork clinked against a plate and then no one moved.

“You can’t do that,” Dan said finally, the words ragged. “You can’t just announce will changes over Yule log.”

“Watch me,” Ellie said pleasantly. “Lawrence can answer your legal questions. It’s Christmas. Let’s avoid Latin.”

There were explosions—predictable, messy, the way fireworks are messy when they tip sideways into a field—and then there were children to send with Caroline to the game room and grown-ups to convert back to humans. There was a moment where my son told his father in front of everyone, “Mom recorded my concert because she knew you wouldn’t come,” and I watched Dan decide whether to be defensive or decent.

He left with Mandy before dessert, muttering about lawyers and fairness and family. Ellie handed me an envelope. Inside were numbers that had the shape of security. The lake parcel. Shares. A chair on the board if I ever wanted it. A paragraph that said there is a way to belong that isn’t begging.

That night on the dock, Uncle Peter handed me a mug with something warming under the cocoa and told me—like a story he was half convinced I already knew—that I am not responsible for other people’s dishonest choices. The wind stung my cheeks. The stars refused to be less beautiful because people had been less kind. I let the frost in my lungs melt.

Part Two

January was paperwork and deep breaths. By March, we could ice skate on the lake, and by May the water had learned to be glass again. Ellie asked me to sit in on a meeting at Green Antiques “just to observe,” and by June I was writing copy for our new online catalog and learning the word provenance from people who pronounce it like a love language. The work lit parts of my brain I’d starved. It turned out I had been practicing to be a curator without knowing it—arranging second-graders and history both into narratives people could live with.

Dan called from Chicago in October to say he was sorry with his whole voice. It didn’t land like a trap. It landed like a late thing, which is still sometimes a true thing. “I miss the version of us that believed love made us better,” I said. “I don’t miss the version of me who thought I had to shrink to fit your family.”

The red convertible appeared in my drive one afternoon when the maples were indecisive about whether they were done. Mandy stood on my porch, shorter hair and hands that couldn’t decide where to be. “We broke up,” she said. “I’ve been in therapy. I’m sorry.”

I let her in. I made coffee with the good beans. She started to cry. It was not the mascara tears of a girl getting what she wants. It was the quiet, humiliating kind. “I didn’t think through,” she said. “I just wanted. And wanting felt like needing so I told myself it was allowed. It wasn’t.”

“I can’t flip a switch and have you be my sister again,” I said. “I can’t make you trustworthy with a speech.”

“I know,” she said. “I don’t even trust me yet.”

We sat at my kitchen island with our childhood between us like a table runner. She left without hugging me. It did not feel like the end of something or the beginning. It felt like acknowledgment, which is what apologies really are when you strip them down.

By late summer I knew I didn’t want to drive back and forth every weekend between a life and a life. We moved into the lake cabin full-time before school started. The contractor expanded the kitchen to accommodate everything I’d learned to make and everything I still wanted to try. I put my writing desk in a corner with windows that pretend to be paintings when the wind is low. Jack joined the robotics club at his new school and built a machine that can pass salt. Sophie’s art teacher asked if she could enter a painting into a competition and I cried in my car where she couldn’t see because sometimes crying is about relief.

On Christmas Eve this year, we hosted our own small dinner. Ellie wore her apron and issued directives in three languages. Peter basted something as if he were conducting a string quartet. The children constructed a gingerbread cabin that looked enough like our house to be flattering. We went around the table and said one thing we had learned since last Christmas. Jack said, “I learned you can build a new tradition and it still feels like Christmas.” Sophie said, “I learned that painting trees makes you understand trees better.” Ellie said, “I learned that anger is not a plan, and a plan is not forgiveness, and forgiveness is sometimes just not wanting to bite anyone anymore.” Peter said, “I learned that online customers ask the same questions in Toledo as they do in Tokyo.” I said, “I learned that I am not invisible to people who have eyes.”

We had hot chocolate by the fire after the children went upstairs with flashlights to read. I dialed a Chicago number and handed each child the phone. Their father wished them Merry Christmas and asked about their stockings. They told him about gingerbread walls that wouldn’t stay up without eating the glue. He laughed, and it did not hurt the way his laugh used to hurt. When they were done, he said, “Tell your mother I hope she has a peaceful holiday.” I nodded at the air because that was almost a gift.

A week later, at our year-end board meeting, Peter introduced the new head of digital for Green Antiques. He made a speech about how sometimes a family business is saved not by the person you expect but by the person you almost forgot you had. He looked at me when he said it and I pretended I didn’t know who he meant because pretending not to know good things is a superstition in our family and I didn’t want to jinx it.

In February, the online store’s catalogue got a spread in a design magazine, and a journalist called me a “curator of memory and material.” I taped the page above my desk because sometimes the names strangers give us fit better than the ones we wore so long they went baggy.

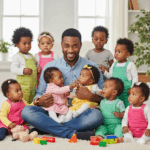

When spring warmed our side of the lake, Amanda sent a card. Inside was a photo of a woman in a circle of toddlers with paint on their hands, and underneath it in her handwriting: Volunteering every Tuesday. It helps. I hope, one day, you’ll let me know how Jack likes salt-delivery robots and how many trees Sophie has painted so I can cheer for them from a distance without making any trouble. I put the card in a drawer. That was the generous thing. I did not put it in the trash. That was also generous.

Dan invited the children to Chicago for spring break. I weighed my fear of their first plane ride without me against the value of knowing their father’s new world. We visited the Field Museum together the first day, all five of us—me, the kids, Dan, and his remorse, which is a better chaperone than I expected. After I flew home, he texted nightly updates like a camp counselor: Sophie touched a stingray at the aquarium. Jack beat me at chess in the hotel lobby. We are inventing a version of co-parenting that does not need to punish in order to protect. It is a craft I wish no one had to learn, and one I am proud to be making something with anyway.

On the anniversary of the barbecue, I cooked strawberry shortcake in my kitchen while the rain pestered the lake. I set it on the table and called my children. I raised my fork. I thought of a hot dog held aloft like a banner twelve months earlier. “Challenge accepted.” It had sounded like a dare then. Now it sounded like a benediction.

Amanda’s joke was right in one small way: there are places where you can vanish and leave nothing behind. What she did not understand is that disappearing from someone else’s small world is not failure. It is freedom. And if you are lucky or stubborn or loved by women who sign contracts with their full names, that freedom will grow into a home where your presence feels like oxygen instead of apology.

On Christmas Day, my grandmother changed her will. She did not do it to punish. She did it to realign gravity. In the year that followed, everything that mattered fell into its proper orbit. My children learned that love is what stays when people leave. I learned that a boundary is not a wall; it is a door with a lock and a welcome mat. My sister learned that wanting doesn’t make having noble. My ex-husband learned the difference between starting over and running away.

And I learned that when you stop begging to be seen and start seeing yourself, people either adjust their gaze or drift out of frame. Either way, the picture gets clearer.

If you are holding a hot dog somewhere today with a laugh aimed at your chest, consider setting it down long enough to pack a box. The opposite of disappearing is not being noticed. It is arriving—for yourself.

—Vanessa

END!

News

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call. CH2

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call …

BREAKING: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in America had dared to ask to do before. CH2

LATEST NEWS: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in…

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour. CH2

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour Part One I…

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments. CH2

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments Part One It’s been said that family…

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About. CH2

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About Part One…

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office. CH2

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load