Husband fumes over stolen $900, demands divorce. I agreed, stopped the allowance. “What’s next_”

Part One

“We’re getting a divorce. You stole the money I gave you every month instead of sending it to my mom!”

Lucas’s breath hit my face hot and sweet with the perfume I never wore. His fingers were a knot in my collar, knuckles white, eyes red with the outrage he’d been nursing all the way home. A cup—our honeymoon cup, the one with the badly painted tulips—spun on the floor at our feet and cracked into three blunt petals.

Something, somewhere inside me that had been stitched too tight for too long, snapped cleanly.

“Fine,” I said. The word felt less like surrender and more like a door clicking shut. “Let’s get divorced.”

I peeled his hand off my blouse and set it gently back on his own chest, as if returning a thing he’d dropped. Then I walked past him, stepped over the tulip shards, and went to pack.

“Olivia! Hey—Olivia!” His voice pitched higher as I moved, as if my name on his tongue were a leash and I’d slipped it. “You’re not hearing me.”

I heard him. I heard the accusation. I heard the echo of his mother’s voice in it. I heard the three years of errand-running and fence-mending and garden-weeding that had come with the envelope of cash I delivered to her door each month, wrapped in the same band as my patience.

My name is Olivia. I’m an illustrator. At twenty-five I was the sort of woman who forgot to eat lunch when a deadline arrived and remembered it only when the vertigo did. I didn’t have time to date, then one day I realized I didn’t know how. Friends were getting married in scenic barns and leaving wineries with place cards tucked into their pockets, and I was leaving ad agencies with a flash drive and a sore wrist. So I did what any modern girl with romantic amnesia does: I went to a matchmaking event and practiced making small talk about coffee brewing methods with strangers.

Lucas had been the only one who didn’t list his salary as if it were a credential. He was a gentleman in all the ways the word gets stretched to cover: held doors, paid bills, called when he said he would, told me he wanted marriage like the line between us deserved a destination. He had smiled at my bad jokes like they were good ones. He proposed in a park with a ring that fit and a speech that made my mother cry. I said yes without doing the math.

After the wedding he suggested we live apart from his parents “for the first few years, to find our own rhythm,” and I had loved him for understanding the way his mother’s eyes slid past mine at dinner. He rented us an apartment ten minutes away from their house—close enough for convenience, far enough for sanctuary. Domestic life was as soft as a TV ad for laundry detergent. He cooked sometimes, he folded towels into rectangles that were almost squares, he kissed me at the sink and made jokes about dishwashers being the unsung heroes of marriage.

A year in, his father died in a traffic accident on a road he’d driven safely for three decades. By the time we reached the hospital, his mother was crying into a paper cup in the family room, and I rounded up tissues and chairs and funeral homes with my phone balanced on my shoulder. Grief made everything slow and bright around the edges. Insurance made it bureaucratic. Money arrived. Lucas said she’d be okay alone. We didn’t move in; she didn’t move in. For a while.

A year later she called to ask for help.

“She got a lump sum,” I said, confused under my best attempt at gentle. “From insurance.”

“She’s lonely,” Lucas said, and I heard the little boy in him, the one who wanted to be the hero of a mother’s story. “She used to go on trips with Dad. She should still go—maybe with friends. I’ll send her nine hundred a month.”

He was transferred to a new department and began living at the office like a rumor. He would come home and sleep like the dead and leave before I finished my first cup of coffee. “I’ll give you the cash right after payday,” he said. “Take it to Mom yourself. I know it’s old-fashioned. But I want you to see her. Make sure she’s okay.”

I did as asked. He’d hand me the money, neat in an envelope, and I’d drive the ten minutes to her house with a smile ready to be pinned on.

The first time, she took the envelope with two fingers, as if money had a smell she found distasteful. “Thank you,” she said, and I thought—well, that wasn’t so awful.

“Since you’re here,” she added, “the garden is a mess. I can’t crouch anymore. My back. Just a little weeding.”

I pulled out the dandelions and the bindweed. I filled the bin. “Aren’t you going to help?” I asked when she returned from the kitchen with a coffee I had not been offered.

“Why would I?” she blinked. “I always do everything myself. You could at least help when you come.”

She sat on the sofa, turned the TV to a talk show I did not recognize, and laughed at jokes I did not hear. I finished when the light went pink and went home with my hands stiff.

It became a ritual. The envelope of nine hundred, the slammed car door, the list disguised as a suggestion. Weeds. Pruning. Laundry. “The washer-dryer is new,” she said. “But it’s hard on the back, the reaching. You’re young.” Vacuuming. Washing the car. “My husband was very particular,” she said. “About shine.”

I rinsed leaves and guilt in equal measure and told myself this was what families did.

A year of support later, she began hinting at more. Not to Lucas. To me. “I live alone,” she said, staring past me at the TV, where a woman was sobbing about a husband who had forgotten an anniversary. “There’s the pension, and my part-time work, and what my son gives me, yes, but at my age there are always extras. Creams. Hair. Repairs. It’s not cheap to look like yourself.”

I wiped the floor and said, “I’ll check the budget when I get home.” At that point, “budget” was Lucas’s word. He gave me his pinched take-home money—rent, utilities, the two credit card bills—and I stretched it like dough. He never showed me his pay stub. He never told me exactly what the cards were buying. He had not been this discreet when we were dating.

Three concise months after that conversation, she started arriving at our apartment instead, the envelope exchange reversed. She’d sit on our couch and pick at invisible lint and tell me what a wife should be. “The entrance,” she said, “is dusty. The neighbor’s dog will pick up grit on their paws. A wife should live for her husband’s reputation. And these shirts…” She plucked at the collar of one of Lucas’s button-downs as if it had offended her. “Wrinkles. You don’t iron.”

She would drink my coffee and eat my toast and tell me about trips she took with friends to hotels I googled later and refused to admit I wanted to see. She would ask for small top-ups. “Just two-fifty,” she’d say. “The girls booked a better place. I can’t be the only one slumming.” Or, “One hundred thirty. Hair.” Or, “Fifty. Bingo.”

Lucas stopped helping around the house. “Mom’s been over,” he would say, smiling as if that were news the apartment would rejoice about. “You should keep things a bit tidier. She worries. You’re home. You can handle it.” He patted my shoulder like the house. He didn’t smell like coffee and toner anymore when he came home. He smelled like bergamot and tuberose, like a perfume you notice because it keeps showing up where it shouldn’t be.

I sighed my work into the night, the glow of my monitor painting me blue. Commissions were good; that was a grace. But grace has limits. The month before the cup broke, I had given my mother-in-law the usual nine hundred, plus an extra nine hundred from my own income. We were two weeks from the next payday when she came with a smile and a bag full of plans.

“My friend’s birthday,” she chirped, as if the question were already answered. “She adores the new brand bag. I’ll need $1,350. And I must look the part. Clothes. Shoes.” She looked at the table, as if I might have laid out bills like cutlery.

“I’m sorry,” I said carefully. “That’s too much this month. Maybe a smaller gift? Or delay? A dinner?”

She stared at me, each wrinkle deepening under its makeup as if offended by budget. “Gifts are gifts because they are given on time,” she snapped. “Unbelievable. Ashamed to think you’re my daughter-in-law.”

She stood. I stood. At the threshold she shouldered me, whether on purpose or because she mistook my body for a doorframe, I do not know. The tray slipped. The tulip cup broke. I looked at the pieces and felt absolutely nothing and then absolutely everything.

After she slammed the door, the apartment paused. The silence was so clean it squeaked. I sat down and considered the shape of my life as it had been, and the shape it could be.

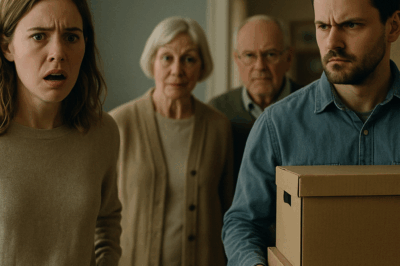

Lucas slammed in an hour later, looked at the floor, looked at me, and reached for my collar. “We’re getting a divorce,” he shouted, but the pitch of it already sounded like a retreat.

He shook me. Somewhere near his ear I could see the place he shaved too quickly in the morning. I could also see the the cheap glitter on the edge of his ear where perfume had caught and dried. I saw that I had been stupid for two years because I had wanted to be loyal for five.

“Thank you for everything up to now,” I said when the earth slid back under my feet. “Send the papers to my parents’ address. There’s nothing else to discuss.”

At my parents’ house, the light was the same as when I was a teenager sneaking in past curfew: warmer than it should be, forgiving despite having already forgiven a hundred times. My mother made rice and eggs. My father put another log in the woodstove and said nothing at all for a whole hour, as if silence were an antiseptic he knew how to apply.

Lucas did not call. Three days later a form arrived, the kind you can print from the internet and sign with the same pen you use for shopping lists, and a note that read, simply: I won’t divide any assets. I had never planned to ask for any. The lack of pretense was almost kind.

I signed.

A month passed. I drew. I answered emails. I made schedules on legal pads and crossed off lines on them with the kind of satisfaction that costs nothing and therefore feels wonderfully expensive. I built a routine that did not require explanations. I was learning the new shape of the day when my phone lit up like a broken neon sign.

Twelve missed calls from Lucas. I considered it, then answered because sometimes the self you want to be needs practice.

“Olivia, what is this?” he blurted, the panic in his voice cutting off the greeting. “There’s no way I can pay this amount with my salary alone.”

“It’s the monthly budget,” I said, and the calm in my voice surprised me. “Did you really think nine hundred a month was enough to support two adults? The shortfall came out of my income. Your credit card bill alone was eighteen hundred. Every month. To say nothing of the cash.”

“What?” He exhaled the word like a man in a cartoon discovering gravity.

“That started about when we started sending your mother money,” I added. “Which is also about when you started coming home smelling like someone else.”

He said nothing, loudly.

“Might I suggest,” I continued pleasantly, “that your mother’s request for a lump sum had less to do with rent and more to do with her new hobby? Host clubs aren’t cheap.”

“How did you…” His voice faltered. “She—she got in trouble at work,” he blurted, seizing another topic the way a drowning man seizes a branch. “She was asking coworkers for advances. The manager ratted her out. They fired her. You did this.”

“She harassed her coworkers for cash,” I said. “They defended themselves. Wonderful for them.”

“And—and my company fired me,” he said quickly, as if stacking disasters could make him taller. “Someone made a complaint. Stalking. It’s not—I mean—”

“The husband of the woman you were sleeping with,” I said, because I had learned how to be a precise person again. “A client of mine.”

Silence, the old merciless kind, returned. Then, small as regret and twice as slippery: “Help me.”

“We’re divorced,” I said. “It’s none of my business. Figure it out. You were the one who made a fuss about getting a divorce without listening to me. And your mother egged you on. Why don’t the two of you keep each other company.”

He said something, possibly a curse, possibly my name, possibly a phrase he’d already used so often it had worn out and meant nothing. I blocked his number. I blocked my mother-in-law’s number. I blocked their calls on my parents’ phones and taught my father to use “Do Not Disturb” without rage.

Iris—my friend who stocks enough supermarket gossip to fill a small-town newspaper—sent a voice memo two weeks later. “She got canned for asking everyone for money. Begged to come back because you-know-who got fired too. Management said—and I quote—no feckin’ way.” Iris has that way of telling you tragedies like they’re punchlines because sometimes that is what keeps you from crying.

As for my mother-in-law, rumors moved like wind through trees. There were whispers of a debt at a host club—a handsome man with painted nails and a sadness she thought she could save with her pension. There were rumors of a shoebox of receipts and scarf-wrapped eggs delivered by a neighbor who wanted to help and didn’t know how. There were images I did not want and therefore refused to entertain, because the point of learning to know your own mind is knowing when to spare it.

I packed my sketchbooks and my laptop and moved to the countryside. My work lived in my computer; my joy lived in the kind of place where the weather is something you smell before you see, and where grocery store cashiers learn your name and then your favorite bread and then the fact that you once dyed your hair purple in college.

My parents’ cat adopted me as furniture. I adopted a habit of walking each evening to the creek that cuts behind the old mill and sitting with my feet in water so cold it shocked every feeling into honesty. On weekends I drove to a farmer’s market and bought too many tomatoes because painting them took longer than eating them and I liked the excuse. I drew for clients in Paris and Tokyo while listening to crickets. I said yes to coffees with friends and no to anything that smelled like apology wrapped in duty.

“What’s next?” I asked myself one afternoon, standing in the kitchen with a lemon half in my hand, the sun peeling my mood like citrus. The question had been Lucas’s once, the sharp rhetorical of a man planning his own benefit. It had been my mother-in-law’s, pressed against me like an obligation. It had been a threat. It had been a performance.

I wrote it on the chalkboard we use for reminders and underneath it, added my answer: Whatever I decide.

Part Two

The irony of remaking a life is that it looks, from the outside, like you have simply resumed it. People who haven’t seen you in three years will say you look well and ask you to remind them which brand of mascara you use, as if the trick to your new lightness lies there and not in the fact that the man who used to stand in the doorway while you cooked and say “gifts are only gifts if they’re on time” is no longer standing there.

In my new town, where everyone knows the postman’s first name and not his last, I became “the illustrator who moved in with her parents” for exactly two weeks and then became “Olivia” again. I joined a book club and discovered that women in their thirties will fight as hard for their favorite paragraphs as they will for their children. I signed up to teach a Saturday morning class for kids on “drawing what you see, not what you think you see,” and spent three hours each week listening to eight-year-olds argue with their pencils about whether shadows are blue or purple. I laughed more than I had laughed in the entire last year of my marriage.

Lucas texted once from a new number. “I’m sorry,” it said. “I was drowning.”

I typed and deleted six answers. Then I sent: “Learn to swim.” Then I blocked him again, because boundaries are like fences—establish them once and your garden is not invaded every afternoon by a dog that isn’t yours.

Iris called to say my mother-in-law had been seen, hood up, at a bus stop, a paper bag in her lap and a look on her face like someone had drawn her eyebrows onto a new expression and she wasn’t sure how to wear it. “Do you feel bad?” Iris asked, not because she wanted a specific answer but because she loves precise questions.

“I feel human,” I said. “I feel like I survived an attempted drowning and I am now the kind of woman who will throw a rope if she has both feet firmly on the shore. I am not yet on the shore. Also, she called me a disgrace because I couldn’t give her a brand name bag for her friend’s fiftieth birthday.”

“I’ll knit you a bag,” Iris said, deadpan. “Brand: Knott.”

On the first warm day of spring, I took my father to the hardware store and we bought lumber and built a table for the back porch. He measured. I held the board simply to look useful. We sanded until our wrists complained. We painted the wood the color of rain when it decides to be beautiful. We waited for it to dry. We ate dinner on it the next night and the night after that.

Death—in marriages or otherwise—has an afterlife. There are paperwork afterlives and gossip afterlives and memory afterlives. There are also the small afterlives of habits—reaching for a second toothbrush that is no longer there, counting portions for a person who doesn’t arrive, checking your phone at 5:30 because it used to be the time someone came through the door and threw his keys in a bowl like he was paying the entry fee for your patience.

I lit a candle in the evenings for three months, because the light we choose changes the way the house feels, and I wanted to feel like I lived in a place where rituals are invented without permission.

About six months after I left, my work took me to the city for a week. I stayed in a small hotel room with a view of the kind of roof where pigeons plan their day. I met clients who had only ever seen my face as a tiny circle on a Zoom screen. I drank coffee I did not make and wore shoes that liked sidewalks. In the lobby on my last morning, a man waved.

Lucas. He was thinner. His eyes had a hollow I recognized. People grieving their own bad decisions always look like this at some point.

“Olivia,” he said, and he didn’t reach for me. “I won’t take much of your time. I wanted to say… I know I can’t fix it. I know I was cruel. I know I was wrong. I’m sorry.”

He said it like a man reading his own autopsy and wishing for a red pen. I waited for the echo of a rehearsal and did not hear it. I stood there and felt compassion, and then I felt gratitude for the compassion, and then I felt the relief that comes when you remember that compassion does not require reconciliation.

“I hope you find a life,” I said. “A good one. I hope you find a way to be the kind of man who apologizes before there is an audience.” I nodded toward the café behind him. “The coffee is good. Not as good as mine, but good.”

He smiled, small and real, and then he left. I watched him go and felt the way wounded things always feel when they see the forest’s edge and realize the trees do not speak, and it is okay to leave them all the same.

On the train home, a woman across from me read a book I love. She pushed a strand of hair behind her ear on the same line I’d underlined twice with a pencil when I was twenty and learning that literature is the only mirror that won’t lie. The line read: “Her life became hers when she took it.” I laughed out loud like the world had made a joke in a language only I understood.

Back home, I finished a project for a client who used the word “gorgeous” in an email in a way that made me believe she understood gratitude. I planted herbs in the window boxes and bought a new kettle and a rug that looks like the sea and told my father I would repaint the porch swing with him when the weather held. I made a bank appointment to open a separate account titled What’s Next_, because sometimes the joke you make about your own life is the map you need to follow it.

The allowance stopped. The harassment stopped. The “are you sure you’re doing enough” stopped. The list of things I wanted to do grew.

I taught myself to row a little boat. I learned to like thunderstorms because they sound like the world reminding you it hasn’t forgotten how to be dramatic. I went to Iris’s birthday and brought a cake I baked myself. I watched as she opened presents. None were brand name bags. All were loud and unnecessary and perfect. She hugged me for too long in the kitchen while the women in the living room argued about whether cilantro tastes like soap and I thought: this is what family is—forgiving enough to stand in an uncomfortable hug, smart enough to argue about herbs.

Sometime in late summer my mother-in-law’s number rang from a landline I did not recognize. The voicemail used the word “help” three times. I listened to it once. I deleted it. I went outside and drank water like it was a practice. I sat in the grass and let a dandelion stain the knee of my jeans. Then I stood and went inside and drew a picture of a dandelion that was far more beautiful than the one in my yard, because that is what artists do with the world—they acknowledge the stubborn and make it art.

The last time Lucas tried to call, it went to voicemail because all of his numbers are blocked. He sent an email instead, a thing that cannot be stopped by boundary settings and therefore feels quaint. “I’m not asking for money,” he wrote. “I just wanted to say: thank you. For stopping the allowance. For leaving. If you had covered for me forever, I would be worse. I’m working nights at a warehouse and learning how to cook eggs without burning them. If you ever need anything… I know you don’t. But if you do—please ask.”

I did not reply. He did not need my forgiveness to be useful. He had found his way to his own penance. That is a story that belongs to him, and to the women he will meet after me, and to the men he will teach to do better.

This is mine:

I am thirty. Three years married and done. I live in a house where the walls remember my childhood and not my humiliation. I have a job I love and friends who buy me bread because they like the look on my face when I bite into it. My father’s hands still know how to steady a board and a heart at the same time. My mother has started telling the story of my divorce like it is a folklore tale with many morals, all of them good.

“What’s next?” is no longer an accusation on someone else’s lips. It is an invitation on mine.

Sometimes it’s as small as buying a basil plant and keeping it alive. Sometimes it’s as big as saying yes to a project that scares me enough to give it the respect it deserves. Sometimes it is driving through town with the windows down and the radio up and knowing that if I saw Lucas at a stoplight the only thing I would feel would be a gratitude so bright it would make the car warmer.

What’s next_ I choose.

END!

News

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in. CH2

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in Part One The evening…

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… CH2

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… Part One…

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house. CH2

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house Part One “Did you really think…

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: ‘Move in with My Parents or Divorce!’. CH2

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: “Move in with My Parents or Divorce!” Part One The…

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything. CH2

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything Part One The worst…

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire. CH2

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire Part One I never planned…

End of content

No more pages to load